Perseverancia (Perseverance)

AHEAD OF ME a van was stopped in the middle of the road. Visions of Nimbus hit by a car flashed through my mind. The family in the van had not hit a yegua tobiano. They were picking nalca to sell in town. They had not seen a black and white horse. Later, I saw a man moving a handful of cows. He had not seen a yegua tobiano.

“But, she has been here, and not long ago,” he said, bending down to examine her tracks in the pumice. “She will be down there.” He pointed to the valley bottom, a place that seemed to me like an eternity away. “That is where my animals always go when they run away.”

The man and I walked together down the pumice-covered road, kicking up small puffs of ash with every step until he turned his cows out into a pasture full of half-eaten bushes.

“Stop and take a rest at the house on your way back. My wife will be there if I am not,” he said, pointing by pursing his lips back up the road behind us.

The small, yellow house a few kilometers behind me had to be his. It was the only occupied house I had seen in days. I had never knocked on anyone’s door and informed the woman of the house that her husband had invited me for tea. If I was going to invite myself in, I had better know his name.

“¿Como té llamas?” I asked.

“Me llamo Feliz,” he said.

How curious, this man who lived on a campo full of ash was called Happy. There were so many things I wanted to know. What had it been like when the volcano exploded? What was it like to live on this campo smothered in ash when all of his neighbors had abandoned theirs? I suspected this man called Happy had a kind of perseverance I could barely imagine. From where did he get it?

Promising to stop by later, I kept walking. I noticed a herd of horses in the distance. There wasn’t a yegua tobiano in the bunch. Far away I saw a light colored horse. Sure it was Nimbus, I saw dark markings that were not there. Behind every bush, I saw a tobiano mare. I was always wrong.

In my mind’s eye, I saw myself haunting this road for weeks, asking every neighbor within a hundred kilometers if they had seen a yegua tobiano, becoming known as the stupid gringa who lost her horse. By late afternoon, I hadn’t eaten for twenty-four hours. I had no horse and no plan.

I had no food and no water, and I was already a long way from camp. The terrifying question, what if I don’t find her, kept creeping forward in my mind. How far could I go in this direction and still make it back to camp? Would I actually turn around without my horse?

Deep inside, I knew the answer and it scared me. During desperate times on long mountaineering trips, I had tapped an immense well of physical energy. I would walk all night. I had done it before.

Near the abandoned house where Nimbus and I had stopped the day before, the rear end of yet another black and white horse stuck out from behind a bush.

This time, it was her!

I crawled onto her back, buried my face in her mane, and wrapped my arms around her neck in a huge hug. Nimbus, my sweet, sweet, Nimbus. Her body relaxed underneath me. She, too, was happy to be found. Instantly I forgave her for leaving me. Who could blame her for wanting to eat sweet green grass?

Instantaneously, all misgivings about who I was and what I was doing with my life vanished. The world was immediately beautiful and my journey, once again, a grand adventure.

But now what? It was late, I was miles from home, and I had no saddle. I gave her a little squeeze with my knees. She started walking. I reached around her neck and tied the lead rope to both sides of her halter, and we were off. Back on the road, Nimbus, still casting her vote for going home, turned resolutely north. I pulled her head southward with equal determination. She turned south, but walked like she was dead. At this rate we wouldn’t get home before midnight. I turned her north and she trotted. I urged her a little; she galloped. When her energy was high, I turned her south again, but this time I kept her at a trot. It worked.

Without the saddle my body ached for the kind of riding I had seen the gauchos doing. They never trotted with the English-style posting—one and two and up and down—that I did. The locals sat perfectly level, their upper bodies still, while their hips and legs swung back and forth to the rhythm of the trot. It was a mystery to me, but more than anything, I wanted to ride like that, and today I was riding home, saddle or no saddle.

A whole day without food and water had made me bold, and my encounter with Feliz had piqued my curiosity. At the front gate of a yellow clapboard house with purple lilac bushes miraculously blooming beside the front door, I tied Nimbus to the fence post with her head up. I couldn’t let even my Nimbus eat the precious little grass that grew in their yard.

A big woman answered the door with a welcoming smile. She wore red basketball shoes laced up her ample ankles and a green sweater that did not match her flowered skirt.

“Pasé,” Susana said, and without asking why I was there, she settled me into the most comfortable spot directly behind the woodstove.

I wanted to ask about the volcano. What was it like the night fire shot into the air? And how did it feel to have all your neighbors move away, to leave you here with your husband on this barren ground with cows that eat bushes? But one does not come in the door asking questions. First, there is maté to drink.

Susana put fresh sopaipillas and homemade cherry jam in front of me. The cherries, she informed me, came from the tree that, despite the volcano, still bloomed outside the window.

“Did you know the volcano was coming?” I asked at last.

“We did because we live close. We saw the ash plume and the fire shooting into the sky at night. Then the ash really started to fall. It didn’t stop for a week. Days passed when you couldn’t see the sun. It accumulated over three feet thick. People’s roofs caved in. We went to live with my sister for three days, but then we came back,” Susana told me. “We used to have sheep. They all died from the ash. Now we have cows. Cows can eat bushes.”

A picture of three young boys hung on the wall.

“One is in Cerro Castillo,” she told me, “and one is working on a remote campo up valley. The youngest one is herding goats in California.”

“Do you hear from him often?” I asked.

“Oh, yes, he called us just last year,” she said. “He will be coming home soon, only another year and a half.”

Again, I suspected that time somehow moved differently in Patagonia.

It was common for young men to leave their parents’ campos to work in the States for a few years. If they were lucky and frugal, they could earn enough money to return and start their own farms. Some of these young men ended up working on good ranches, where they were well paid and respected. Others did not. Sometimes these men were looked upon and treated as illegal aliens, but they were working legally and most couldn’t wait to get home. Their opinion of the outside world, or at least the United States, was formed by these experiences. I hoped Susana’s son was on a good ranch.

Feliz had been born on this campo, as was his father before him. Susana had lived here since her wedding day. No mere volcano was driving them off their land.

“Doesn’t it get lonely without neighbors?” I asked.

“Oh, yes, but the grass will come back, then the neighbors will as well, at least those who have not sold out,” Susana said.

“When will that happen?” I asked.

“Oh, things get better all the time. Ten years will help, and in thirty, forty years this place will have grass this high,” she said, pointing to halfway between her red sneakers and the hem of her flowered skirt. Susana was not a young woman.

I looked again at the photo of the boys on the wall. Would they also come back with the grass? It was obvious that the future of this land and the rebound of abundant life on this campo was not for her generation, but the next.

I didn’t want to leave Susana’s comfortable home, but I needed to get to camp by dark. I excused myself, sure that someday I would make it back for a visit, bringing with me a big loaf ofsweet bread to share.

We kept up a good trot. Nimbus also realized the serious need to get home soon. Of course, camp had even less of the same sparse grass that Nimbus had abandoned the night before. At the end of a long day of walking and trotting without a saddle, there was no part of my body that didn’t hurt. Selfishly, I wanted to crawl into my sleeping bag and call it a night, but it was obvious what I needed to do. I packed camp, loaded Nimbus, and went another seven kilometers. Well after dark I set up camp in a wet, bumpy, buggy, miserable spot beside a swamp, but it had that one important commodity of camping with horses: Grass.

At the next town, Bahia Murta, the silhouette of an old church broke the skyline. The weathered wooden shingles on the steeple matched the gray of the clouds. Surrounded by a cute picket fence and fields of blooming lupines, the old church called to us to take a break. The gate was open and inviting.

On a beautiful summer evening in 1977, a tremendous landslide upstream on the Rio Engaño had sent a torrent of water, mud, and broken tree trunks raging through the town of Bahia Murta. The flood destroyed several houses and picked others up in their entirety and deposited them downstream. Somehow, some say miraculously, it missed this church. Rumor also has it that the church bell rang by itself in the night to warn the villagers. As I looked around at the three or four remaining houses, it was hard to believe that the village had once been a town of a thousand people.

On the outskirts of the old village, I camped on a beach where finely ground volcanic ash produced the softest sand I had ever felt between my toes. The turquoise-blue waters of Lago General Carrera, the second largest lake in South America, stretched into the distance. The scene could have been the Caribbean. That evening as I walked the beach, the sunlight slid under a layer of clouds at the mouth of the river, turning the Rio Engaño to liquid silver. My sleeping bag laid out on the shore, I slipped into a soft sleep, soothed by the gentle lapping of waves. Little did I know that I was destined to return to the church at Bahia Murta, and I would not be alone.

The next day, I crossed the Rio Tranquilo on a steel and concrete bridge. Six years earlier, I had stood on the banks of the Rio Tranquilo, with an overloaded backpack and a dozen NOLS students, watching a man on horseback cross the river. That moment had changed the course of my future. Today, a new gravel road wound westward to within twenty miles of the Pacific coast. A short drive—if, of course, you had a car—could get you to within a few hundred meters of the same glacier our NOLS group had taken a month to reach.

The people of the town of Rio Tranquilo and the campos to the west had been anxiously awaiting this road for decades. In 1993 I had stumbled upon faded markers in the woods flagging the intended route of what some claimed would one day soon be a road.

I had always dreamed of returning to this valley on horseback, but the freshly laid gravel of the new road would be horrible for my horse’s feet. Furthermore, I had no desire to walk a gravel road through what once had been wilderness, leaving me to return by the same route, eating the dust of whizzing automobiles.

I needed to buy food. Not wanting to make a spectacle of myself, I unloaded Nimbus on the outskirts of the town of Rio Tranquilo and walked in. The food selection in the only small shop I could find open was slim, as usual. Once again, my diet would consist of pasta, tomato paste, cookies, and white bread.

When I returned, an old man in a tattered blue sweater and a pair of worn-out mud boots was walking slow, contemplative circles around my disheveled pile of gear.

“Buenas tardes,” I said, announcing myself and claiming that odd-looking pile of junk, in what turned out to be his yard, as mine.

Antonio greeted me with a huge smile. The mystery was explained. It was a gringa.

“Is it okay if my things are here?” I asked.

“Si, pero adentro,” he said as he started to pick up my gear and carry it inside his fence.

It was obvious I would be staying awhile. Antonio insisted on carrying the saddle, even though he was much older and smaller than I am. He led me to a two-room shack. People in rural Patagonia don’t usually have the kind of excess we are accustomed to in the United States, but this man struck me as poor.

In Alaska, I had lived for seven years in a twelve-by-twelve-foot cabin most people would call a shack, but the difference between Antonio’s home and mine was striking. Every niche of my small cabin was crammed full: climbing gear, skis, more clothes than a person should own, sleeping bags, tents, pots and pans, artwork, and piles and piles of books. Antonio’s possessions included a sink for the water he let run constantly, a bench by the woodstove for us both to sit on, a pot, a bowl, a spoon, and a knife. In the other room I could see a wooden bed neatly made up with heavy woolen blankets. No books, no television, no radio; for entertainment he looked out the window.

Antonio was fifty-nine, although he struck me as older. He was still fit, but decades of hard work making a living cutting trees were etched into his face and hands. Here was a man who could tell you about wood.

Ciprés, which grows in the wetter regions in the far west, is good for fence posts. It doesn’t rot, but it can take more than a year to dry. Coihue, the evergreen version of lenga, grows just to the west and is used for hardwood floors, tables, and axe handles. Antonio stoked the small firebox of his stove with lenga.

“Lenga is good firewood. It burns a long time,” he told me.

I had long desired a Chilean-style, wood cookstove for my cabin in Alaska, but if I were burning spruce in a firebox that small I would need to stoke it almost constantly.

“What do you think about the new road?” I asked.

“It’s wonderful,” he said. “You can drive nearly to the coast. Best of all, everyone is working!”

I couldn’t help noticing that he didn’t have a car to drive to the coast, nor was he working, but I kept my mouth closed. Like many of his neighbors, Antonio had never been anywhere overrun with cars and roads. The few people I had met who had been to Santiago or even the U.S. had a different opinion.

“It’s terrible, too many roads, too much noise,” they all agreed, but the idea of that kind of development ever happening in Patagonia remained unfathomable.

In the 1970s, the construction of the trans-Alaska pipeline cut a road through 270,000 square miles of northern Alaska, effectively cutting nearly in half the biggest chunk of unmolested wilderness left in the United States.

The road into the Rio Tranquilo Valley was cutting the wilderness I loved into smaller and smaller chunks, but I kept my viewpoint to myself. While my strong feelings about wilderness were deeply ingrained, I also held firmly to my conviction that as a visitor here, it was not my place to decide.

In locations where news travels mostly by word of mouth, inaccurate information can become rampant. I had heard that a Canadian mining company was looking for a place to put an aluminum processing plant, and Patagonia, with its huge, free-flowing rivers, was a prime candidate to placate the world’s hunger for cheap electricity.

“Have you heard anything about anyone wanting to put an aluminum processing plant in this valley?” I asked Antonio.

“No, but that would be good, too,” he said, making a split-second decision.

I didn’t agree, but I had no idea if the stories I had heard were even true. I also didn’t believe environmental issues eight thousand miles from home would have anything to do with my life.

Almost 1,500 kilometers north of Rio Tranquilo a company called Endesa was busy damming Chile’s second largest river, the Bio-Bío. I had heard about the controversy behind damming this world class whitewater river, but—like everyone else—I had plenty of things on my worry list. My priorities were: Grass for my horse, a place to sleep, keeping myself dry when it rained. Still, I felt a sense of urgency about this trip. How many other horse trails would be replaced by roads a year from now? One locked gate, one “no trespassing” sign, and my journey would be over. Patagonia was changing. I had no idea how fast.

I hadn’t traveled an hour out of Rio Tranquilo when I saw a sign announcing, “La Hacienda.” That’s odd, I thought, most people don’t have a sign on their house.

“Pasé, descansa un poco.” A young guy on horseback invited me in for a rest. Thinking he was the boy of the family, I was surprised when he introduced me to his wife, Llorena, and their three-year-old daughter, Valentina. Llorena wore clean, fashionable jeans, a brilliant green T-shirt, and a bright, inviting smile. Beside her I felt old, travel worn, drab, and dirty. Valentina, a cute little girl with straight dark hair and huge brown eyes, peaked at me from behind her mother’s jeans.

Their house was small but also exceptionally bright, cheery, and clean.

“I love it here,” Llorena told me. “Todo esta tranquilo aquí.”

I understood, the quiet country life grabbed me as well. I noticed a small washing machine in the corner.

“It is amazing,” I said. “You have electricity and running water way out here.”

“Oh, this isn’t even the hacienda,” she said.

Fabio and Llorena were the cuidadors of someone else’s fancy estate. The hacienda, a huge house made of stone and glass, sat conspicuously on the shore, a motorboat tied to the dock. Excessively extravagant, it dominated the landscape. Fortunately for me, the kind of opulence many people envy never appealed to me. I wouldn’t trade my simple cabin in the woods in Alaska for anyone’s mansion.

“The dueño lives in Santiago and comes down maybe once or twice a year,” she said. “We get to live here by this gorgeous lake all the time. The best thing is that each day we get to do everything with our daughter. The dueño has his priorities all wrong. Our life is the best possible life.”

I doubted much of the world would see it my way, but I agreed with Llorena.

The next day I marched up a side valley into the mountains. Once again, I would not be traveling south, but I was beginning to care less and less about some arbitrary definition of progress. I needed to get away from the dust and noise of the carretera.

Deep in the Leones Valley, dozens of perfect campsites beckoned. Each one had plenty of grass, easy access to the river, and views of glaciers spilling into the valley. I chose one and settled in.

Nimbus wandered away during dinner. I no longer panicked about such things. There was a gate not far behind us. When I went to retrieve her, Elvira was out in her garden. We talked over the fence like neighbors. She and her friend, Sophia, were running the campo while her father was in the hospital in Coyhaique. To my surprise, neither of these women, who have lived nearby all their lives, had ever been to the head of the valley.

“Want to come with me tomorrow?” I asked, ecstatic about the idea of having companions.

“Oh, no,” Elvira said. “We have way too much work to do. Some other day.”

The next day, as I trotted up valley, miles of spectacular scenery rolled easily by. I understood that it was the culture of excess I came from that had produced the remarkable combination of time and money that allowed me to travel up this valley for the simple, pure joy of it. On this perfect Patagonia spring day, guilt easily slipped away.

Miles into the valley, well beyond where anyone lived, I came across a sign announcing money available to improve road access to the area. Oh, Elvira will be thrilled, I thought. She can finally go see the lake, if, of course, she can find a car. Meanwhile, I felt deeply content to be in this valley in what I was just beginning to understand was a very special time in Patagonia’s history.

The terrain got steeper and the forest denser. At the end of the trail, I tied Nimbus in a grassy spot and took off on foot. I needed to get to that lake the same way, in my previous life, I had needed to get to a summit. Cresting one rocky ridge after another, I realized there could be hundreds of these old moraines. This desire to push on had gotten me into serious trouble before. I didn’t want to leave Nimbus tied too long in the woods. This was wild country. A tied horse would be easy prey for a puma.

However, the late November days were long. My heart pushed oxygen through my body as I hurried along, glad that kind of drive was still in me.

Suddenly, Lago Leones and the immense glaciers of the Campo de Hielo Norte, the most northerly ice field in the Southern Hemisphere, burst into view. Mount Haydes, a 3078-meter glaciated giant, rose impressively from the far end of the lake. Fifty kilometers to the west, the San Rafael Glacier flowed down the other side of the same ice sheet, discharging icebergs into the Pacific Ocean.

Eighteen thousand years ago, the Northern and Southern Patagonian Ice Fields were one humongous ice sheet, and the entire verdant valley we had just traveled through was locked beneath a mile of ice. A huge piedmont lake far larger than Lago General Carrera drained east into the Atlantic. The explosive melting of the Baker River basin split the ice fields, and the giant glacial lake at its base turned its flow westward to the Pacific. Today, at only four percent of its original size, these two Patagonia ice fields constitute the third largest fresh-water reserve in the world. Five hundred square kilometers of Patagonia’s ice fields have disappeared in my lifetime. Climate change—actually, change of all types—was happening fast in Patagonia.

As I began my descent to the shore, a large brown animal watched me from the woods. What was a horse doing so deep in the dense forest? Then I noticed antlers and big ears like a mule deer. It was a huemul. Thick, furry, one-pronged antlers and the distinctive dark V on his face gave him away as a young male.

He froze. I froze. Both of us were unsure whether we had been seen. In more than half a cumulative year in the wildest parts of Patagonia, I had seen exactly one track and one scat of this elusive, endangered animal.

The Tehuelches had seldom entered the depths of the forest to hunt, leaving the huemul amazingly docile and innocent. In the early 1920s, the huemul’s first contact with settlers and guns quickly led to the endangered species list. Subsisting on a fraction of its former domain, the huemul was protected in the 1980s.

Knowing that having two eyes close together gave me away as a predator, I tried not to fix my gaze upon him as I wandered in his general direction. A glimpse of his tawny coat in the late-afternoon sun reminded me it was past time for me to turn around, but I simply wanted to be with him. Eventually, he slipped quietly into the brush. I was still unsure if he knew he had been spotted. I rushed back to Nimbus, excited to tell Elvira about the huemul. On second thought, maybe I shouldn’t tell anyone.

The next morning, rain was coming down in a deluge. My tent rattled in the wind. I had no desire to go anywhere, but my linear North American brain reminded me I had just taken two extra days to go up a valley that did not lead south. Late in the day, I set off into the storm. I hadn’t made but a few kilometers in a southerly direction when a small man in a bright yellow raincoat stopped me on the road.

“¿Por qué tu viajas en un día como esté?” he asked.

“Porque, voy a Cochrane,” I said, as if simply going to Cochrane was a good enough reason to be traveling on this kind of day.

“?Por qué no te quedas aquí?” he said, nodding in the direction of his house, a waiting woodstove, and another round of maté.

“Gracias,” I said, explaining that I had a friend waiting for me in Cochrane.

A month earlier I had told my friend, Samuel, my trip to Cochrane would take a month and I would look him up as soon as I arrived. A month had already gone by and I was still a long way from Cochrane. But the truth was, there was not a person on the planet concerned with my whereabouts that day.

At the next bend the brunt of the Patagonia wind hit me hard in the face. Here, smack in the middle of a set of latitudes known as the Roaring Forties, westerly winds roar around the globe unimpeded until they hit their first and only landfall—Patagonia. I had made a mistake. Horizontal rain came in sheets. Wind worked water in through every opening in my rain gear. Soon, I was soaked up to the knees and down to the elbows. At first, small icy trickles, then streams of cold water, ran down between my breasts. Eventually, the storm pushed cold water through my Gortex and into every pore of my body. A familiar pre-shiver tightness welled up between my shoulder blades.

“Porque soy tonta,” was what I should have told the man in the yellow rain coat. Because I am foolish, because I am gringa, because I think I am so important that the world cares what I do today. So what if I had traveled only a little more than an hour? So what if I took yesterday off and drank tea all morning? Only a fool would travel in this miserable weather.

I thought of turning around and trying to find his house. Every step forward made it less likely that would happen. An occasional trot helped keep both of us warm, but I wondered how long my body could keep pumping out the needed calories. I needed to eat. In order to eat I needed to cook. In order to cook I needed to find a sheltered spot. The word porfiado stepped to the forefront of my mind. Puro porfiado, pure stubbornness, had gotten me into this, and now pure stubbornness would have to get me out. Native people all over the world understood how to remove themselves from physical pain and toil by singing and chanting. As windy mile after cold, windy mile dragged on, I made up a rough song in Spanish for Nimbus.

“Que buena la yegua. Que cruce los río. Que saltan los tuncos.” What a good mare, who crosses the rivers and jumps the logs. “Esa yeguita tan bonita,” I sang to my beautiful little mare. It seemed to work. Nimbus kept moving. Maybe she, too, understood that our other option was freezing.

Late in the day, we found a protected place to camp behind some giant coihue trees out of the wind.

The next day we arrived in the small village of Puerto Bertrand where I had a friend who ran a guide company. As I walked through Jonathan’s garage, which was filled with neatly organized shelves of outdoor equipment, and into a kitchen wallpapered with maps, I stepped directly back into the culture from which I’d come. Within moments we were sitting at his kitchen table, maps spread out before us, beers in hand. We talked easily in English. River running, mountain climbing, love of the world’s wild places, we had a vocabulary in common. How long had it been since I had spoken without first deliberating? How long since I had discussed anything except the cows?

“Right here you can cross the Baker River on a swinging bridge,” he said, pointing less than a day’s travel farther south. “From there you can ride beside the Colonia River and stay off the carretera all the way to Cochrane.”

“That’s great,” I said, “but I would have to cross the Baker again to get to Cochrane.”

Thirty miles downstream, the Baker would look like the Mississippi.

“There will be a barge that can take horses right where you need to cross.”

Later that afternoon, I made myself useful patching rafts. Tourist season was still a month or two away, so we labored in an easy, unhurried manner. As in every other household in Patagonia, when neighbors stopped by, work ceased and a maté session began.

Jonathan’s mother was visiting from the States. We ate good food and chatted easily in English. Inside the house was like living with an American family. Outside, a quaint Patagonian village and a tranquil lake with a backdrop of snow-covered mountains were only footsteps away.

Only a block from Jonathan’s doorstep, I sat on a giant, rounded granite boulder beside the Baker River. The sun bore down intensely on my shoulders. Upstream the turquoise waters of Lago General Carrera flowed quietly into Lago Bertrand. From where I sat sunning myself—my near hypothermic episode already a faint memory—the Rio Baker poured out of Lago Bertrand and flowed deep, blue, and strong all the way to the Pacific Ocean. I daydreamed of casting off in a small boat and following the river’s powerful flow to the sea. It would be a decade before I would feel the power of the Baker beneath my hull.

Puerto Bertrand boasted three hundred residents on a good day. I considered making it three hundred and one. I could ask if Jonathan would hire me for the summer. But I could feel it, my pull, like that of the Baker, was still flowing powerfully southward.

On the next sunny day we flung the garage door open, letting musty camping gear absorb the fresh air of the coming season. I mounted Nimbus, waved goodbye to my friends, and headed southward.

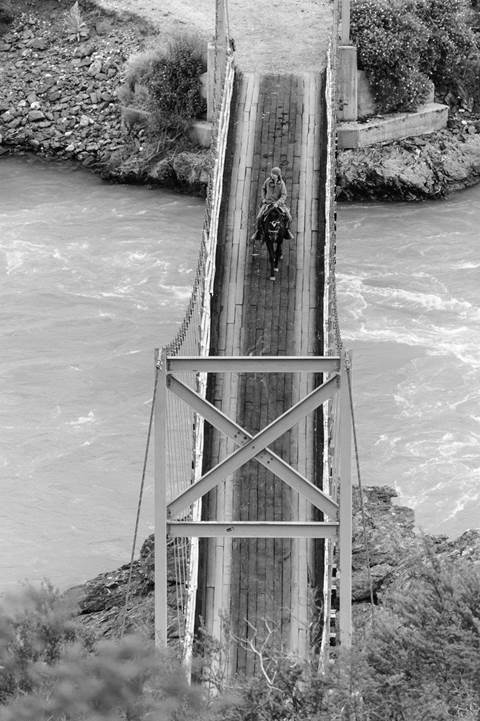

Off the carretera at last, I crossed the Baker downstream of town on a swinging bridge over an immense canyon. Traveling through high mountain valleys of uncut lenga forest, I broke out in song again, this time for joy, for sunshine, for the forest, and the hundreds of tiny yellow birds that gathered all around me. Old trim lines on the landscape marked the remnants of ice ages that had retreated up valley long ago. Occasionally, views of long, snaking glaciers appeared through small openings in the woods, and I understood vividly, if only for a moment, that our little slice of time is nothing of significance.

In well over a month on the trail I had grown into a delightful sense of living in the moment, of being precisely where I was. These days, that peaceful state of mind would periodically vanish, as thoughts of the outside world crept into my consciousness. Part of me wanted to stay forever in every valley I passed through, at the same time, I was anxious to get to Cochrane. Logically, it didn’t matter. I had no solid plans beyond arriving in Cochrane and giving Nimbus and, yes, myself a good long rest.

Mornings and evenings I turned Nimbus free. She usually just hung around. During the day, I took her off the lead rope and walked ahead of her. I had taken to walking whenever the terrain was steep or when I was loaded down with a new supply of groceries to save Nimbus’s knees. In reality, I walked most of the time. With nowhere else to go and nothing better to do, Nimbus tagged along like a puppy. I finally felt the kind of connection with my horse that I wished we’d had from the beginning. But I knew in my heart I wasn’t doing her any favors by taking her on this trip. Her knees were bad and they weren’t getting any better because of me.

Descending one last time into the Baker River basin, the trail branched and twisted and threatened to disappear. A man on horseback approached us from behind. Nimbus stopped. Whenever we saw people that meant break time.

A thin, older man sat astride a well-worn saddle on a leggy young alazán. He had a puesto not too far away. It was unspoken that we were invited to follow him to his simple shelter. He rode ahead, opening each gate for us, but Nimbus and I had been practicing. After we walked through, I nudged Nimbus slowly in beside the gate. Nimbus helped push it closed with her shoulder, and with a long reach, I slipped the wire over the post. Still a bit slow and awkward, we were getting it.

“Are you from this part of the country?” I asked him.

“No, soy de Chiloé,” he told me.

Patagonia was primarily colonized by three groups: huasos from northern Chile, gauchos from Argentina, and chilotes from Chiloé. The island of Chiloé, often considered the northern border of Patagonia, has its own culture, rich in mythology and folklore. I recognized the indigenous heritage of the islanders in his strong cheekbones and wide, easy smile.

“How long have you lived around here?” I asked.

“Twenty-five years,” he said.

I understood all too well. Even longtime Patagonians were still identified by the region they had come from. That is exactly how it would always be for me, as well. Culture runs deep. If I lived here the rest of my life, I would still be an outsider.

José put the maté water on, then proceeded to count for me each of his many blessings: two turkeys with eight baby turkeys, eleven chickens, two cows with young calves so plenty of fresh milk, a good sheep dog with two fat puppies, and, of course, the main necessity of life, a good, strong horse.

José pulled out a piece of mutton from a cool back room and cut into a fresh onion from town. I unpacked the last of my noodles to add to the soup.

Shortly thereafter, a younger man arrived, dismounted, and tied his horse beside Nimbus. He showed no sign of surprise at finding a gringa washing dishes in the front yard. The visitor lived up valley, near the end of the Colonia River. This was obviously his normal lunch stop. He was coming from visiting his wife and kids in town. I was four hours from Cochrane.

Distance is time in Patagonia. No one could comprehend when I asked how many kilometers away something was, but hours by horseback was easily understood. I would undoubtedly double his time, but still, I was close!

As I went to leave, I noticed a small spot of blood on Nimbus’s right front fetlock. The heads of the shoeing nails on her right rear foot were sticking out just enough that when she walked she nicked her front foot. Her rear shoe was worn thin along the leading edge and quite loose. On inspection, all of her shoes were ground thin. I needed to make them last one more day.

Instead of asking one of the men for help, I grabbed a hammer and a flat board, propped Nimbus’s foot up on the board, laid my heavy file on top of the nail, and re-bent the nails to tighten her shoe. I had seen this done dozens of times, but I was totally pretending that this was something I knew how to do. José didn’t jump in to help. Either he was less than enthusiastic about approaching the hind feet of a horse he didn’t know or my make-believe show of competence was working. I was learning. The confidence and independence I had in my life in Alaska was coming to me here.

The next morning, rain was falling hard. No longer the gringa who goes out in the worst of storms because she thinks there is somewhere better to be than here, or that there will ever be a better time than now, I sat snug in my tent, confident that Nimbus and I would not get hurt, lost, or die, and that someday soon I would arrive in Cochrane nothing worse than tired and dirty. The scared girl who had walked out of Sergio and Veronica’s gate felt like a stranger. Something deep inside told me to treasure these moments, that this, indeed, is the best life has to offer.

When the rain eased, I saddled up feeling the same excitement to see what was around the bend that I did every morning. But today it was mixed with an uneasy feeling I recognized as approaching change.

Sometimes people refer to their transition after a wilderness trip as returning to “the real world.” That phrase confuses me. What part of life is more real than waking with the sun, working your way through an intricate landscape, eating when you are hungry, finding shelter when it rains? Being responsible for your own needs and making the decisions that will keep you and your animals alive seemed at this point far more real to me than endlessly sending messages off into cyberspace. All day I was moody and confused. I had been making this radical transition between wilderness and life in town frequently for decades. Why then was I feeling disturbed? Wasn’t arriving in Cochrane supposed to be the consummation of a huge goal?

Town would mean complications in a life that had become exceedingly simple. The problems of the outside world would have, for the first time in more than a month, the opportunity to find me. Most of all, I knew that I would have some big decisions to make about Nimbus.

Again, I arrived on the banks of the Baker River. No bridge spanned this huge and powerful river, but just as Jonathan had promised, a simple ferry system was set up at the crossing. The ability to cross the Baker at this point had been key to opening the incredibly rich Colonia Valley to ranching. Long before the arrival of the automobile in Patagonia, ferries and bridges on major horse trails were considered part of the country’s transportation system.

Suddenly, from apparently nowhere, other people on horseback appeared. The ferry operator spotted us, and the balsa, a flat-bottom barge slung between taut cables, slowly drifted across the river in our direction. The barge bumped softly onto our shore, lowered a wooden loading ramp, and three horses and riders stepped aboard. A slight change of angle was set by adjusting the length of sturdy chains, and the power of the river alone drove us quietly and efficiently toward the other side.

As I drifted across the Baker River that day on a simple wooden ferry powered by the flow of the current, the fact that the fate of this river would someday determine the future of Patagonia, and to a large degree my own life’s path, was the furthest thing from my mind.