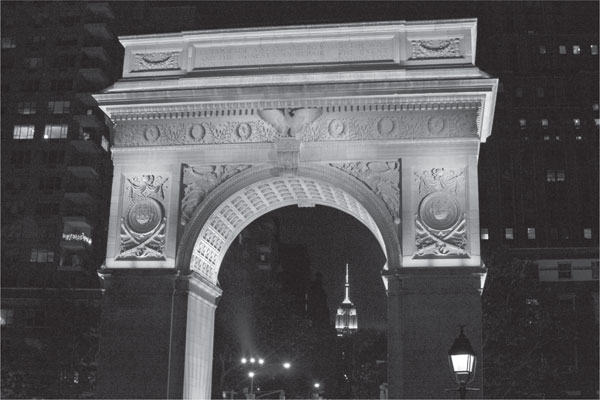

Washington Square Arch framing the Empire State Building. Courtesy of James Maher.

CHAPTER 2

FIRST CAPITAL OF THE COUNTRY

GEORGE WASHINGTON SLEPT HERE

Contrast the New York City of 1898 with the New York of one hundred years earlier. In the late eighteenth century, New York occupied only the tip of Manhattan Island. The street map reveals the geography of early New York. Lower Manhattan is a jumble of streets that twist and turn and bear distinctive names like Hanover, Beaver, Water, Houston and Pearl.

Many of these street names provide insights into seventeenth- and eighteenth-century New York. Pearl Street is named for the seashells once found there. Pearl Street ran along the shore of the East River before landfill extended Manhattan to South Street in 1800. There once was a wall along the outer edge of the city to protect the earliest European settlers in New York, the Dutch, from their enemy, the English. This explains the name “Wall” Street. Beaver Street was the center of the very important fur trade that created fashionable hats and large fortunes in the late eighteenth century. Notably, the seal of the City of New York includes the image of a beaver.

Early European exploration of New York was a precursor of the future city’s cultural mix. In 1524, Italian Giovanni da Verrazano, sailing for the French, was the first European to lay eyes on Manhattan. The Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, which connects Brooklyn and Staten Island, is named in his honor. Today, if you arrive in New York City by ship, you will most likely go under the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. Henry Hudson, an Englishman sailing for the Netherlands, became, in 1609, the first European to explore what would be named the Hudson River along the west side of Manhattan. Hudson named Staten Island for the governing body of the Netherlands: the staten, or states general.

The Netherlands, the greatest sea power in the world in the early seventeenth century, grasped the potential of New York for trade. A small group of Dutch colonists landed on Governors Island in 1624. Officials of the Dutch West India Company established a trading outpost at the mouth of the Hudson River and called it New Amsterdam after their country’s capital city. They named the broader area New Netherlands. In 1648, the Dutch built the first wharf to handle the shipping trade on the East River. One hundred years later, there would be multiple wharfs with one-third of the world’s trade shipped out of New York City.

But the Dutch were not the first to inhabit the land. About fifteenth thousand Lenape Indians lived here, moving from shore to inland in different seasons. To ensure the establishment of successful trade routes, the leader of New Amsterdam, Peter Minuit, sought a peaceful accommodation with the local inhabitants. The story is that Minuit bought Manhattan from the Lenape in 1626 for approximately twentyfour dollars’ worth of beads and utensils. It is probable that the Lenape had a different approach to property rights than the Europeans, not intending to relinquish the land completely. Whatever their intentions, the Lenape legacy lives on in the name Manhattan; it derives from a Lenape word meaning “island of many hills.”

The Dutch continued their advances in the area, settling Brooklyn, named for Breuklelen, a town in the Netherlands, in 1636. The name for another borough, the Bronx, also has Dutch origins. Jonas Bronck settled the area for the Dutch in 1639. Bronck, however, was born in Sweden. Other Dutch naming rights extended to Haarlem after the city in the Netherlands of the same name. Later, the spelling was changed to Harlem. The Bowery on the Lower West Side of Manhattan takes its name from the Dutch word for farm: bouwerij. And Coney Island derives from the Dutch name for rabbit—conyne—once plentiful in the area.

Though Dutch control of Manhattan was short-lived—about forty years—their contributions to what would become New York and the United States have been long lasting. Unlike English settlers in New England, the Dutch did not attempt to impose a state religion on New Amsterdam. They practiced a tolerance that was a feature of their seventeenth-century homeland. Eager to expand the trading post’s economic output, New Amsterdam accepted French Protestants, English Roman Catholics, Quakers and those fleeing the strictures of New England Puritanism. Eighteen languages were spoken in New Amsterdam. Diversity was as much a characteristic of early Manhattan as it is now.

Jews first arrived in Manhattan in 1654, fleeing from Brazil, where Portuguese victories over the Dutch and ensuing intolerance made their existence untenable. The director general of New Amsterdam, Peter Stuyvesant, initially objected to their presence, but his bosses at the Dutch West India Company in Amsterdam overruled him. The Jewish population in Manhattan became an integral part of the town.

Freedom and tolerance did not, however, extend to those of African origin. The slave trade was robust. Slaves worked in the fields and at the port. The Dutch began bringing Africans into New Amsterdam in the 1620s. At first, they seized them from Portuguese ships. Later, the Dutch brought them directly from Africa. At a time when there were fewer than two thousand people living in New Amsterdam, the slave population numbered three hundred.

By the mid-seventeenth century, the balance of power had shifted in Europe with major consequences for the Americas. The English surpassed the Dutch as the dominant sea power. In North America, the British had already defeated the French in the French-Indian War of 1754 to 1763, becoming the continent’s powerhouse. The English had colonies in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Pennsylvania and Virginia. The Dutch New Amsterdam stuck out like a great interruption of the extended English control. The English eyed New Amsterdam and wanted it. England was looking not only at opportunities in trade; it also needed outlets for its booming and underemployed population. Overseas settlement provided a great escape hatch for too many people with too few jobs who otherwise might become disruptive at home.

In 1664, King Charles II dispatched a naval force of four war ships and two thousand men under the command of Richard Nicolls to take the Dutch New Amsterdam outpost for England. Peter Stuyvesant, with only a small garrison to defend the town, saw reason and surrendered. The English took over, and Nicholls became governor. The English extended to the Dutch inhabitants of Manhattan their policy of freedom of religion and trade—two cornerstones of continued New York growth and development.

Though Stuyvesant returned to the Netherlands, he later resumed his life in New York and died here. He is interred at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery on land he once owned. There is a 1915 statue of Stuyvesant at the church. He is also immortalized in Stuyvesant Street, Stuyvesant Square and Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan and the Bedford-Stuyvesant area of Brooklyn.

English possession provided naming rights. Instead of New Amsterdam and New Netherlands, New York became the name for the settlement and territory. The important Dutch outpost of Fort Orange became Albany. All were named in honor of the younger brother of King Charles II, who was the Duke of York and also the Duke of Albany. He later became King James II of England. The English named Queens, the largest of the five New York boroughs, for the wife of King Charles II of England, who ruled from 1660 to 1685. Queen Catherine of Braganza was originally from Portugal.

English control of New York continued from 1664 until 1783, with a brief interruption in 1673, when the Dutch returned and took over Manhattan for fifteen months before permanently losing it to the English. The English made New York a royal colony in 1685 and retained sovereignty until the American Revolution brought independence. Ironically, in 1688, in the Glorious Revolution, the Dutch army landed on the coast of England, marched toward London and installed the Protestant daughter of Catholic King James II on the throne of England. Her husband was the Dutch William of Orange. They ruled jointly as King William and Queen Mary. Their rule was notable in that it established the supremacy of Parliament over the throne in England. This, in turn, would greatly influence American views of how government should operate.

Under British rule, New York continued the African slave trade. By the mid-eighteenth century, 20 percent of the eleven thousand people living in Manhattan were slaves. Of all the towns in North America, only Charleston, South Carolina, had a greater slave population. Slaves performed household labor, worked in the growing shipbuilding industry and served as apprentices in various trades. Under Dutch rule, some slaves had worked to earn their freedom. The English stopped this practice. They also precluded slaves from burial in churchyards, such as the one at Trinity Church. The important ceremony of individual burial would occur in the African burial grounds north of the city and away from the population center.

While little concerned about freedom for African slaves, New Yorkers became increasingly focused on their own personal Liberty. New York played host to the first organized American resistance to British taxation. In October 1765, representatives of all thirteen of the American colonies gathered for the Stamp Act Congress at New York City Hall. They were there to protest “taxation without representation,” which London had proposed to do in the Stamp Act. The Stamp Act Congress resulted in the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, which helped achieve the deSired result: British Parliament repealed the Stamp Act.

The Sons of Liberty of New York had organized in response to the Stamp Act. They were principled defenders of freedom and, when they thought necessary, public agitators. To celebrate the repeal of the Stamp Act, they erected a “Liberty Pole” in 1766 near the British military barracks in what is now City Hall Park. British soldiers took it down, and the Sons of Liberty erected another. This back and forth continued a few more times. Today, a symbolic Liberty Pole stands close to City Hall. As in Boston, there was a tea party in New York Harbor to dump tea into the sea to protest the taxation of this important commodity.

With tensions between England and the colonies propelling them toward conflict, George Washington became commander in chief of the Continental army in June 1775. Washington successfully drove the British from Boston after the Battle of Bunker Hill. Both Washington and the British immediately recognized that New York City was the next big prize.

Political momentum reinforced the action on the battlefield when the American Patriots meeting in Philadelphia in the Second Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. When the declaration was read to the public in New York City on July 9, the New York Sons of Liberty rushed to Bowling Green and toppled the large equestrian statue of King George III that had stood there since 1770.

The largest land battle of the Revolutionary War was the Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn. In this military engagement on August 27, 1776, British commander Sir William Howe defeated General George Washington and his Continental army. Not only were there twice as many British as American forces—twenty thousand compared to ten thousand—but Howe also surprised Washington in a nighttime flanking maneuver and nearly managed to surround the Continental army. Sensing a hopeless situation, George Washington rushed to evacuate the remaining nine thousand American troops from Brooklyn to Manhattan. A dense fog helped conceal their escape from the British. There are annual reenactments of the Battle of Long Island on its August anniversary in Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, where the battle occurred.

While Washington did win a battlefield victory against the British at Harlem Heights shortly thereafter, he recognized the peril his soldiers faced when up against the far superior British forces. George Washington and the Continental army evacuated New York on November 16, 1776, not to return for seven years. Washington led his troops north into Westchester County, New York, then into New Jersey and on into Pennsylvania. New York City remained under British control for the duration of the Revolutionary War. British admiral of the fleet Richard Howe, also known as Lord Howe, and his brother Sir William Howe, general of the British army, made New York their North American headquarters. Under British rule, many New Yorkers remained loyal to the Crown.

George Washington, eager to learn about British war plans, deployed spies to the Loyalist stronghold of Manhattan. One of the most famous American spies was Nathan Hale, a former schoolteacher from Connecticut. Hale was on a mission to New York City when the British captured him and hanged him on September 22, 1776. The brave twenty-one-year-old is remembered for his inspiring last words: “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.” An American hero, he is remembered in a statue by Frederick MacMonnies in City Hall Park.

While there were no more battles in New York City, a great fire in September destroyed a quarter of Manhattan. Both the British and the Americans accused each other of arson. And American casualties in New York exceed those in all the Revolutionary War battles combined. From 1776 to 1781, over ten thousand captured Patriots died on British prison ships moored in the East River, succumbing to neglect, disease and malnutrition. These Americans are memorialized and some of their remains interred at the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument in Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn.

As the Revolutionary War continued, George Washington and the Continental army, persevering without adequate arms, food or pay, kept the British at bay. King George III saw many battlefield wins but no victory. This was enough for the government of France to increase support for the American Revolution. The American-French victory over the British at Yorktown in 1781 was the final battle of the American Revolution. On September 3, 1783, a war-weary Britain signed the Treaty of Paris and relinquished its thirteen American colonies and all lands to the Mississippi River.

New York would be the last American territory the British left. On November 25, 1783, British forces under Sir Guy Carleton evacuated New York City. That same afternoon, General George Washington and his Continental army made a triumphant return. For many years, Evacuation Day, November 25, remained a day of great celebration in New York City. Its importance diminished after President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed in 1863 a national day of Thanksgiving set for the third Thursday of November. Later, Congress changed Thanksgiving to the fourth Thursday in November. After World War I and the United States’ alliance with Great Britain, the evacuation commemoration disappeared altogether.

In appreciation of the American victory and the November 25 return to New York City, George Clinton, the first governor of New York, hosted a dinner in honor of George Washington at Fraunces Tavern in Manhattan. George Washington dined again at Fraunces Tavern on December 4, 1783, and said goodbye to his officers in the Continental army. Immensely popular, Washington could have stayed on indefinitely as general. He would have held great sway over the young country. With his farewell, Washington helped create a true American democracy under civilian, not military, control.

George Washington retained a special place in the hearts of grateful New Yorkers. New York City’s Common Council, a precursor of today’s city council, honored him in 1785 with “the Freedom of the City.” In response, George Washington wrote the council a letter and referred to New York State as the seat of the empire. Some historians point to this letter as the first reference to New York as “the Empire State.” Today, New York State is commonly known as the Empire State, and “Empire State” is written on New York automobile license plates. The most famous building in New York City is the Empire State Building.

During the Revolutionary War, a national government had been formed under the Articles of Confederation, adopted in 1777 and ratified by the states in 1781. Under this form of government, individual states held power. The federal government could not raise taxes, pay the army or effectively conduct foreign policy. There was no president, only a Confederation Congress that periodically met but accomplished little. From 1785 to 1789, the Confederation Congress met in New York City.

Recognizing the shortcomings of the Articles of Confederation, some pushed for the Constitutional Convention that convened in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787. The result was a constitution that framed a new, stronger federal government. With the ratification of the Constitution in 1788, New York City became the first capital of the United States. Pierre L’Enfant, a French engineer who had left his homeland to support the American side in the Revolutionary War, remodeled the former British colonial City Hall on Wall Street to house Congress and the executive and judicial branches of the new federal government. City Hall became Federal Hall. The first session of the First United States Congress convened on March 4, 1789, at Federal Hall in New York City. It was in New York City in the summer of 1789 that James Madison, serving as a representative from Virginia, introduced twelve amendments to the Constitution. The states would ratify ten of these amendments that define the basic rights and liberties of Americans. These first ten amendments to the United States Constitution are known as the Bill of Rights.

By the terms set forth in the Constitution, the Electoral College voted for the first president of the United States and unanimously chose George Washington. Informed of its decision at his Virginia plantation, Mount Vernon, Washington made his way to New York City for an inauguration originally set for March 4 but delayed by bad weather until April 30.

April 30, 1789, was clear and cool as George Washington stepped onto the second-floor balcony of Federal Hall to take the oath of office of president of the United States. Robert Livingston, chancellor of New York, administered the oath. John Adams, vice president, stood at Washington’s side. On this solemn occasion, George Washington spoke the words laid out in the United States Constitution. He also added his own touches to the ceremony: he swore the oath on a Bible. In closing, Washington added, “So help me God.” Every president since 1789 has sworn the oath on the Bible and added the words “So help me God.” Today, a large bronze statue of George Washington stands where he took the oath of office as our first president. The statue by sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward has been in this location since 1882.

After his inauguration, George Washington delivered his inaugural address in the Senate chambers in Federal Hall to the assembled members of Congress. He then walked to St. Paul’s Chapel to worship. Later, President Washington would return to his residence, a rented home at 1 Cherry Street that also served as his office. This home was demolished in the nineteenth century. There is a plaque on Pearl Street under the Brooklyn Bridge to remember the first presidential mansion.

In New York City, in Federal Hall, Congress created the United States government of today and the first four departments of the executive branch: Treasury, State, War and Justice. For secretary of the treasury, George Washington chose New Yorker Alexander Hamilton, an ardent advocate of the new federal form of government. Thomas Jefferson became secretary of state, Henry Knox became secretary of war and Edmund Randolph became attorney general. Washington nominated John Jay, a New Yorker, to be the first Supreme Court chief justice.

New York City remained the federal capital until 1790. The decision to relocate the United States capital out of New York City was part of a grand compromise that resolved several difficult issues threatening to tear the young country apart. Over dinner in New York City in 1789, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison agreed that the northern states, with their much heavier Revolutionary War debt, would gain relief through the federal government’s assuming the debt. In return, the southern states would realize their goal of seeing the United States capital move to a more geographically central location. President George Washington had the authority to select the location. He chose a site on the banks of the Potomac River near Georgetown, Maryland. It was here that a new district would be created to house the federal government.

Pierre L’Enfant, who had successfully remodeled New York City’s Federal Hall, would prepare the plan for this new United States capital city: Washington, named for George Washington, in the federal District of Columbia, named for Christopher Columbus. The national government would move to Washington, D.C., in 1800. Until then, Philadelphia would serve as the temporary capital of the United States. Moving the federal capital out of New York City in 1789 reassured many Americans who felt that concentrating political as well as economic power in a single city would threaten the young democracy.

As the United States approached the nineteenth century, New York City would no longer be the political capital of the young nation. However, New York City would increasingly become the nation’s financial, commercial and cultural capital.

YOUR GUIDE TO HISTORY

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN NEW YORK

1 Bowling Green, across from Battery Park • Lower Manhattan

212-514-3700 • www.nmai.si.edu • Free

This New York branch of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, the George Gustav Heye Center, is housed in the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House. This museum has an important and extensive permanent collection of archeological items, modern and contemporary art, photographs and video from tribes across the United States and also from Canada and South and Central America. Rotating exhibits, musical and dance presentations and significant educational outreach create a museum that provides stimulating insight into Native American life and artistic endeavors.

The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House building is an important part of the visit. On the site where the Dutch Fort Amsterdam once stood, it is one of the most beautiful Beaux-Arts buildings in New York City. Dating to 1907, it is the work of famed architect Cass Gilbert. Sculptor Daniel Chester French designed the massive exterior statues representing the continents of America, Africa, Asia and Europe. The building is named for Alexander Hamilton, a New Yorker. He was the first secretary of the treasury of the United States, serving under President George Washington. Hamilton is credited with creating the national banking system.

The National Archives at New York are also in the building. There is a small welcome center and exhibit gallery of original United States documents. The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House is a National Historic Landmark.

BOWLING GREEN

Broadway at Whitehall Street • Lower Manhattan

www.nycgovparks.org

At this location, Peter Minuit negotiated with the Lenape Indians for the sale of Manhattan to the Dutch in 1626. This is the oldest public park in New York City. It was built in 1733 next to the original location of the Dutch Fort of New Amsterdam. The original eighteenth-century fence is still in place. For a while in colonial times, the locals enjoyed the popular sport of lawn bowling here. The Sons of Liberty tore down the 1770 equestrian statue of King George III after the July 9, 1776 reading in New York City of the Declaration of Independence. Today, the statue on Bowling Green is the Charging Bull described in Chapter 14.

THE BATTERY

Lower Manhattan

www.thebattery.org

This twenty-five-acre park is built on landfill that has extended the tip of Manhattan since the mid-nineteenth century. Its name derives from the artillery batteries the original Dutch residents placed here to protect the city. Today, it is a lovely park with many pleasant features, gardens and memorials. The Battery Conservancy, a nonprofit organized in 1994, maintains this New York City park.

There is a lovely waterfront promenade with views of the Statue of Liberty and of Lower Manhattan. The gardens include the Bosque Gardens, designed by Piet Oudolf. Bosque means “grove of trees” in Spanish. The Gardens of Remembrance flower in tribute to those who died on September 11, 2001. The Labyrinth, a path for reflection, has been a feature of the Battery since September 11, 2002.

Historical references are strong and numerous. They are captured in a totally modern and artistic way at the Peter Minuit Plaza near the Staten Island Ferry Terminal in the New Amsterdam Pavilion. The pavilion was designed by UNStudio to look like a flower. At midnight, the pavilion flashes different colors in honor of Peter Minuit, whose name translates to “midnight” in English. A very recent addition, the Seaglass Carousel is a contemporary version of the popular merry-go-round. In this case, luminescent fish rather than horses move through light projections that give the rider the feeling of being under water. The carousel acknowledges the former presence in the Battery of the New York Aquarium, housed in Castle Clinton from 1896 to 1941.

The East Coast Memorial remembers the 4,601 American servicemen who died in World War II combat in the Atlantic Ocean. The Sphere, originally at the World Trade Center and severely damaged on September 11, 2001, is here, at least temporarily, to remember those who lost their lives that terrible day. There are memorials to Korean War veterans, the American Merchant Marines and the Coast Guard, and also there is the Marine Flagstaff.

Americans of many nationalities have sought to honor their distinguished countrymen in statues and memorials that include: the Statue of Giovanni da Verrazzano, the Netherland Memorial, the John Ericsson Statue, the Walloon Settlers Memorial, the Peter Caesar Alberti Marker, the Norwegian Maritime Monument and the John Wolfe Ambrose Memorial. A statue, The Immigrants, remembers those who entered this country through Castle Clinton. The visit to Castle Clinton is described in Chapter 7. Markers in the Battery honor Emma Lazarus and Admiral George Dewey.

GOVERNORS ISLAND

10 South Street at Whitehall Street • Lower Manhattan

www.batterymaritimebuilding.com • www.govisland.com • www.nps.gov/gois • Admission Fee

The ferry to Governors Island departs from the Battery Maritime Building. The island is open to visitors from May to September, with ferries operating during those months. Governors Island is the joint responsibility of the Trust for Governors Island and the National Park Service.

The 172-acre island off the southern tip of Manhattan is a gem, offering entertainment as well as a large green park to provide respite from the concrete of the city. A series of events is planned for the warm weather season, including concerts and art installations, often with an international flavor. A relatively new addition to the island’s attractions is the “Hills.” Four separate hills of varying heights provide visitors with beautiful panoramic views of Lower Manhattan and the Statue of Liberty.

The name Governors Island dates to the colonial period when the island was the preserve of the British governors who ruled the city. After the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War and the British military’s departure from New York, the island hosted part of the system of fortifications built to protect the city from the British in the event of renewed conflict. Although the United States and Great Britain again took up arms against each other in the War of 1812, no fighting occurred here.

The National Park Service staffs and offers free tours of the two military forts built after the end of the Revolutionary War and before the War of 1812. The classic star-shaped Fort Jay, dating to 1798, was named for John Jay, then governor of New York and the first Supreme Court chief justice. Castle Williams is named for Colonel Jonathan Williams of the Army Corps of Engineers, who designed the fort in 1811. The United States Army had a major post on Governors Island from 1794 until 1966. The site is a National Monument.

BATTERY MARITIME BUILDING

10 South Street at Whitehall Street • Lower Manhattan

www.batterymaritimebuilding.com

Before your ferry departure for Governors Island, take a moment to look around the 1909 Beaux-Arts Battery Maritime Building of cast iron with lovely, decorative ceramic tile. It is the work of the Walker & Morris architectural firm. The ferry runs in the summer months.

JAMES WATSON HOUSE

7 State Street • Lower Manhattan

Exterior Only

This 1793 home, enlarged in 1806 by architect John McComb Jr., was originally built for James Watson, the first Speaker of the New York Assembly and a United States senator representing New York. Today, it serves as the rectory of the Shrine of Saint Elizabeth Seton. For many years in the nineteenth century, the building served as a hostel for young Irish women immigrating alone to the United States who were at great risk as they landed in New York. The building is on the National Register of Historic Places.

AFRICAN AMERICAN BURIAL GROUND NATIONAL MONUMENT

290 Broadway at Duane Street • Lower Manhattan

212-637-2019 • www.nps.gov/afbg • Free

Begin at the visitor center located in the Ted Weiss Federal Building on Broadway. This National Park Service site provides informative exhibits on the lives of Africans brought to New York as slaves during the colonial period. Although New York City served as the host to the first United States Congress, which wrote the Bill of Rights detailing our most fundamental rights as United States citizens, slavery continued here. New York State passed a law in 1799 that provided for the gradual emancipation of slaves. Slavery in New York State was finally abolished on July 4, 1827.

After the British banned burying Africans in public cemeteries, they provided a burial ground for them beyond the limits of Manhattan. Africans and their descendants followed sacred rites for more than fifteen thousand individual burials in the six-acre grounds that existed here in the eighteenth century. City growth and development overtook the burial ground. Excavations in 1991 for the Ted Weiss Building uncovered the forgotten human remains.

Walk around the corner from the visitor center to the monument on Duane Street for a moment of reflection. The Circle of Diaspora signifies the cultural diversity of the Africans who arrived in this country. The Ancestral Chamber not only represents the soaring African spirit, but it also symbolizes the ship holds in which so many slaves were brought against their will to America. The Ancestral Reinternment Ground is where 419 human remains uncovered during the excavation are now buried. The remains were reburied in a 2003 traditional African ceremony attended by many luminaries, including Maya Angelou. The site is a National Monument.

FRAUNCES TAVERN

54 Pearl Street at Broad Street • Lower Manhattan

212-425-1778 • www.frauncestavernmuseum.org • Admission Fee

The museum, four joined buildings taking up a city block, opened in 1907. The tavern building dates to 1719. It became a popular tavern after 1762 under proprietor Samuel Fraunces. Today, the museum offers lectures, concerts and special events, as well as tours and displays. Its focus is the history of the tavern and New York City during the colonial era, the Revolutionary War and the early days of the United States. The guided tour includes the Long Room, where George Washington said farewell to his Continental army officers on December 4, 1783, as he prepared to resign his military commission after the conclusion of the Revolutionary War. The Clinton Room, where George Washington dined to celebrate Evacuation Day, is also part of the tour. Several galleries on the upper floor of the museum display American memorabilia, including early flags. When New York City served as the first capital of the United States, the building provided office space for the Departments of Foreign Affairs, Treasury and War.

FEDERAL HALL NATIONAL MEMORIAL

26 Wall Street • Lower Manhattan

212-825-6990 • www.nps.gov/feha • Free

Park Rangers provide guided tours of the building, which is a memorial to George Washington and to the creation of the American government. Federal Hall became City Hall after the United States capital departed New York and moved to Philadelphia in 1790. The original building where George Washington took the oath of office as first president of the United States was demolished in 1812. The current building dates to 1842, when it was the New York City Custom House. John Frazee was the architect.

The Bible on which George Washington swore his presidential oath in his 1789 inauguration is on display. This Bible was printed in 1767. It is known as the St. John’s Bible, as it belongs to St. John’s Masonic Lodge 1. Other presidents who took the oath of office on this Bible were President Warren B. Harding in 1921, President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953, President Jimmy Carter in 1977 and President George H.W. Bush in 1989. The large bronze statue of George Washington by sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward has been in this location since 1882. The statue stands on the approximate spot where Washington took the oath of office as our first president. The statue is a popular venue for visitors who seek to have their photographs taken with the father of our country. In addition to this statue of George Washington at Federal Hall, there are statues of Washington in Washington Square Park, which was named for the first president, and in Union Square.

There were several events that occurred in the original Federal Hall that were important to American democracy. In 1735, a newspaperman named John Peter Zenger was tried for writing articles critical of the royal governor of New York. The trial found Zenger innocent of libel, setting a precedent for the important principle of freedom of the press. The royal governor lost another fight when he failed to prevent the Stamp Act Congress from meeting in the hall in 1765, thus ensuring the promotion of freedom of assembly. These and other basic rights were codified when James Madison introduced the amendments to the Constitution that would become known as the Bill of Rights when Congress was meeting in Federal Hall in 1789. Federal Hall housed the offices of the Senate, the House of Representatives and the president.

It is notable that Congress convened a session in Federal Hall on September 11, 2002, one year after 9/11, to demonstrate the American commitment to democracy in the face of terrorism. This was only the second time in history after the federal government moved to Washington, D.C., in 1800 that Congress met outside of the United States capital. The site is a National Memorial.

NATHAN HALE STATUE IN CITY HALL PARK

City Hall Park • Lower Manhattan

An American hero, Nathan Hale is remembered in a statue by Frederick MacMonnies in City Hall Park. The statue has stood here since 1893, the centennial of the British evacuation of New York City at the end of the Revolutionary War. At one point, experts believed that this was where the British hanged Nathan Hale, but that location is in dispute. The body of Nathan Hale was never recovered. The best way to see the statue is to take a tour of City Hall as described in Chapter 9.

TRINITY CHURCH

75 Broadway at Wall Street • Lower Manhattan

212-602-0800 • www.trinitywallstreet.org • Donation

Trinity Church first opened for worship on this site in 1698. However, the original building burned in the Great Fire of 1776. A second building was later demolished for structural reasons. This church edifice, a beautiful Gothic Revival–style building designed by Richard Upjohn, dates to 1846. The church tower, at 280 feet, was once the highest spire in New York City—an early skyscraper. Trinity has one of only two complete sets of twelve change-ringing bells in North America. Volunteers pull the ropes that make the bells peal on Sundays and for special occasions. The churchyard is also important. It is the final resting place of several notable Americans: Alexander Hamilton, Robert Fulton and Albert Gallatin. Within the churchyard there is also the Society of the Cincinnati Plaque in honor of the nation’s oldest patriotic organization, founded in 1783. Trinity is an active Episcopal church with regular services. Together with St. Paul’s Chapel, it operates as Trinity Wall Street.

ST. PAUL’S CHAPEL AND CEMETERY

209 Broadway at Fulton • Lower Manhattan

212-602-0800 • www.trinitywallstreet.org • Donation

After his inauguration as president of the United States on April 30, 1789, George Washington walked to St. Paul’s Chapel to worship. Within the chapel is a replica of the pew box where Washington sat. The Great Seal of the United States hangs above the pew box. Among the notable objects within the chapel is the “Glory” altarpiece designed by Pierre L’Enfant, architect of the remodeled 1789 New York Federal Hall and of the plan for Washington, D.C. L’Enfant also helped restore St. Paul’s Chapel while he was in New York City.

St. Paul’s Chapel, built in the Georgian Classic Revival style, opened for worship in 1766. This building, a National Historic Landmark, survived the Great Fire of 1776. Even more remarkably, it survived the terrorist attack of September 11, 2001, that destroyed the nearby Twin Towers and many surrounding buildings. Because of this, it is now affectionately called “the little chapel that stood.” Within the chapel are many remembrances of 9/11 and of the thousands of volunteers who used St. Paul’s as a base of operations in the aftermath of the attack. St. Paul’s Chapel is an active place of worship. Together with Trinity Church, it is Trinity Wall Street.

ST. MARK’S CHURCH IN-THE-BOWERY

131 East 10th Street, 10003 • Manhattan/East Village

212-674-6377 • www.stmarksbowery.org • Donation

This is the oldest site of continuous worship in New York. The church building is more recent, dating to 1799. This church, which is within the St. Mark’s Historic Village, is on land that once belonged to Peter Stuyvesant. Peter Stuyvesant is buried here. The statue of Stuyvesant dates to 1915.

COLUMBUS CIRCLE

8th Avenue, Broadway, Central Park South and Central Park West • Manhattan/Midtown

There are several statues of Christopher Columbus in New York City. The most notable is the one by Italian sculptor Gaetano Russo, erected in 1892 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the Italian explorer’s discovery of the New World. In the nineteenth century, Italian Americans, growing in number and influence in New York City, supported this statue as recognition of their presence. All official distances to and from New York City are measured at Columbus Circle.

THE MOUNT VERNON HOTEL MUSEUM & GARDEN

421 East 61st Street • Manhattan/Upper East Side

212-838-6878 • www.mvhm.org • Admission Fee

Constructed in 1799 as a carriage house for Mount Vernon, an estate in New York named for George Washington’s Virginia plantation, the building became the Mount Vernon Hotel in 1826. In 1833, the owners converted it to a family home until early in the twentieth century. It opened as a museum in 1939. The Colonial Dames of America own and operate the museum. The museum was formerly known as the Abigail Adams Smith Museum, named for the daughter of President John Adams who owned land here with her husband, Colonel William Stephens Smith.

The building is restored to its time as a hotel. New Yorkers would travel up from the city, which ended around 14th Street, to this location, then in the countryside. Interpreters offer guided tours of the eight furnished rooms that represent comfortable New York life in the 1820s and ’30s. There are many public events, including summer concerts in the lovely garden.

HAMILTON GRANGE NATIONAL MEMORIAL

414 West 141st Street • Manhattan/Harlem

212-668-2208 • www.nps.gov/hagr • Free

This is a National Park Service site with ranger-guided tours of the period rooms. Alexander Hamilton was one of the most influential of the Founding Fathers. Born in the West Indies, he came to New York in 1772 as a teenager. Educated at King’s College, now Columbia University, he became an advocate of American independence and of a strong federal government. Hamilton served as aide-de-camp to General George Washington. He fought at Yorktown.

Hamilton was the first United States secretary of the treasury in President George Washington’s cabinet. In many ways, Hamilton was the creator of the modern American banking system. In honor of all that Hamilton did for the young country, his image is on the ten-dollar bill. This will change, however, in 2020, when a woman, to be selected in voting by the American public, will appear on the ten-dollar bill.

Alexander Hamilton spent the last two years of his life in this 1802 home. Although the home has been relocated several times in an effort to preserve it, it is on land that Hamilton once owned. Sadly, Hamilton would engage in a duel with Thomas Jefferson’s vice president, Aaron Burr, in 1804—a duel he lost. Hamilton was able only briefly to enjoy this beautiful Federal-style home designed by architect John McComb Jr. The building is a National Memorial.

MORRIS-JUMEL MANSION

65 Jumel Terrace at West 160th and 162nd Streets • Manhattan/Washington Heights

212-923-8008 • www.morrisjumel.org • Admission Fee

Tours of the Palladian-style mansion, a National Historic Landmark, are self-guided or guided. Morris-Jumel has been a museum since 1904. It hosts frequent musical and other events. Built by British colonel Roger Morris, this 1765 home and 130-acre estate was originally known as Mount Morris. George Washington, general of the Continental army, used the home as his military headquarters in the fall of 1776. He was staying here when he defeated the British at the Battle of Harlem Heights. As president, George Washington would return to the home. In July 1790, the president and Vice President John Adams, as well as Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and Secretary of War Henry Knox, enjoyed a memorable dinner here. In 1810, Stephen and Eliza Jumel bought the estate. Stephen died in 1832 from pneumonia. Eliza remarried in the home in 1833 to Aaron Burr. Their marriage was short lived, lasting only ten months. They divorced the day of Aaron Burr’s death. It was Aaron Burr who killed Alexander Hamilton in an 1804 duel.

DYCKMAN FARMHOUSE

4881 Broadway at 204th Street • Manhattan/Inwood

212-304-9422 • www.dyckmanfarmhouse.org • Admission Fee

Where there were once many farmhouses in a rural, agricultural area, now there is only the Dyckman Farmhouse, built around 1784. The Dutch colonial home opened as a museum in 1916 to help visitors understand eighteenth-century New York. A small formal garden surrounds the house. It is a National Historic Landmark.

BUILDING 92 AT THE BROOKLYN NAVY YARD

63 Flushing Avenue • Brooklyn

718-907-5992 • www.bldg92.org • Exhibits Are Free/Fee for Tours

During the Revolutionary War, the British prison ships where many Americans died anchored here. Commissioned as a naval yard in 1801, it remained one of the most important naval shipbuilding facilities until its closure in 1966. Building 92, the former residence of the marine commandant, was designed by Thomas U. Walter, one of the architects of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. Built in 1857, Building 92 now hosts rotating exhibits. Tours of the Brooklyn Navy Yard explore the history of the industrial park that produced some of the most legendary United States Navy ships in the history of our country. This includes the USS Maine, the USS Arizona and the USS Missouri. A menu of tours includes bike tours of the facility, photography tours and one of the most popular: the World War II tour. Today, the yard is home to many small artisans and crafts industries.

GREEN-WOOD CEMETERY

500 25th Street • Brooklyn

718-210-3080 • www.green-wood.com • Free

Founded in 1838, this 478-acre cemetery also serves as a park. The beautiful landscape and impressive array of statuary helped make it a major tourist destination by the mid-nineteenth century. It offers magnificent views of New York City. DeWitt Clinton, Boss Tweed, conductor Leonard Bernstein and artist Jean-Michel Basquiat are among the many notables buried here. The cemetery’s historical importance includes the fact that the Revolutionary War Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn, was fought on this land. There are annual reenactments of the battle in August. Visitors may prefer a self-guided tour or a guided Historic Trolley Tour. The site is a National Historic Landmark.

LEFFERTS HISTORIC HOUSE

In Prospect Park • Brooklyn

718-789-2822 • www.historichousetrust.org • Free

Pieter Lefferts built this house in 1783. Of Dutch ancestry, Lefferts served in the Continental army during the Revolutionary War. The home was moved from its original site to Prospect Park to preserve it from encroaching development in the early twentieth century. Today, Lefferts House is a museum of the life of an agricultural family in Brooklyn during the 1820s.

PRISON SHIP MARTYRS’ MONUMENT

Fort Greene Park • Brooklyn

www.nycgovparks.org/parks/fort-greene-park/monuments

President-elect William Howard Taft attended the November 1908 dedication of this monument to remember the more than 11,500 men and women who died on the British prison ships anchored in the East River during the Revolutionary War. The monument, consisting of a simple, tall column with one hundred steps leading up to it, was the work of famed New York architect Stanford White. The bronze ornamentation is by sculptor Adolph Alexander Weinman. Under the monument is a vault containing the remains of a small number of those who died on the ships.

Fort Greene Park is named for American Continental army general Nathanael Greene, who was responsible for constructing Fort Putnam to defend New York from the British. Fort Putnam once stood in this park. After the Americans lost to the British in the Battle of Long Island, they surrendered Fort Putnam and retreated to Manhattan.

WYCKOFF HOUSE

5816 Clarendon Road • Brooklyn

718-629-5400 • www.wyckoffmuseum.org • Admission Fee

Visiting Brooklyn today and experiencing its very urban vibes, it is difficult to appreciate that this area was once one of the most productive farmlands in the United States. The Wyckoff House Museum provides an opportunity to remember those earlier times. This is the oldest existing house in New York State. Pieter Claesen came to New Netherlands in 1637 from what is today part of Germany. Claesen worked off his indenture, married and bought a farm and one-room house where he and his wife raised eleven children. He would later add the surname Wyckoff. His descendants would remain on the farm until 1901. The museum opened in 1982. It offers tours of the house and gardens and educational outreach programs that include “Colonial Life” and “African American Life.” The house is a National Historic Landmark.

KINGSLAND HOMESTEAD AT QUEENS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

143–35 37th Avenue, Flushing • Queens

718-939-0647 • www.queenshistoricalsociety.org • Free

Built between 1774 and 1785, after 1801 this home belonged to Joseph King and his descendants until well into the twentieth century. The house, home to the Queens Historical Society, has been open to the public since 1973.

THE VAN CORTLANDT HOUSE MUSEUM

Broadway at West 246th Street • The Bronx

718-543-3344 • www.historichousetrust.org • Admission Fee

This is a beautiful 1748 Georgian-style home with exquisite eighteenth-century furnishings. The land was a large wheat plantation developed by merchant Jacobus Van Cortlandt, a wealthy and distinguished New Yorker of Dutch descent. His son Frederick built the home. George Washington used the home as his temporary headquarters during the Revolutionary War before he evacuated New York. The National Society of the Colonial Dames in the State of New York operates the home, which is owned by the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. The House Museum provides educational tours for students and frequent lectures on period history. The site is a National Historic Landmark.

VAN CORTLANDT PARK

Broadway and Vancortlandt Park South • The Bronx

718-430-1890 • www.vcpark.org • Admission Fee/Free

The 1,100-acre park, New York City’s fourth largest, is on what was once the Van Cortlandt farm. It provides the setting for the Van Cortlandt house. The park has considerable amenities, including Van Cortlandt Lake, the nature center, a pool and running trails. Van Cortlandt Golf Course, which dates to 1895, was the first municipal golf course in the country.

BARTOW-PELL MANSION MUSEUM

895 Shore Road • The Bronx

718-885-1461 • www.bartowpellmansionmuseum.org • Admission Fee

Robert Bartow bought land that had belonged to Thomas Pell and his heirs since the mid-seventeenth century. Bartow built this gray stone mansion with Greek Revival interiors, moving in with his family in 1842. The home opened as a museum in 1946. Its mid-nineteenth-century furniture and décor are on display; the museum also offers rotating exhibits. All tours of the home, which is a National Historic Landmark, are guided.

VALENTINE-VARIAN HOUSE

3266 Bainbridge Avenue • The Bronx

718-881-8900 • www.bronxhistoricalsociety.org • Admission Fee

This Fieldstone house, built by Isaac Valentine in 1758, became the property of the Varian family in 1791. In 1968, it opened as a museum of the history of the Bronx with exhibits and guided tours. It is the home of the Bronx Historical Society.

THE CONFERENCE HOUSE

298 Satterlee Street • Staten Island

718-984-6046 • www.conferencehouse.org • Admission Fee

On September 11, 1776, the leader of the British military forces in the colonies, Lord Howe, met in this house with three representatives of the rebellious Americans: Ben Franklin, John Adams and Edward Routledge. The purpose of the conference was to make a last effort at reconciliation. However, the British price—revocation of the Declaration of Independence—was too high. The Americans left the conference, and the Revolution continued. The house is now a museum. It is a National Historic Landmark.

HISTORIC RICHMOND TOWN

441 Clarke Avenue • Staten Island

718-351-6057 • www.historicrichmondtown.org • Admission Fee

Historic Richmond Town today comprises of one hundred acres within four separate sites with thirty structures that date from the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries. This includes a tinsmith’s shop, a carpenter’s shop and a basket maker’s house. Living history enactments provide a good look into the history of Staten Island and New York City. Voorleezer’s House, a National Historic Landmark, in Richmond Town is the oldest surviving schoolhouse in the United States.

In 1661, a group of Dutch and French settlers led by Frenchman Pierre Billiou asked Dutch governor Peter Stuyvesant for land on Staten Island. This became the first permanent settlement on Staten Island. Billiou built a house there that still stands today. Subsequent descendants added to the structure so that today it is known as the Billiou-Stillwell-Perine House. The museum provides a good overview of the history of Richmond Town. The name “Richmond” comes from the Duke of Richmond, who was an illegitimate son of British king Charles II.

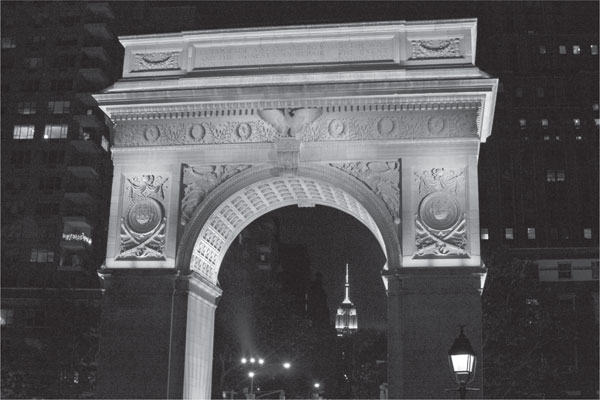

Washington Square Arch framing the Empire State Building. Courtesy of James Maher.