Francis Ledwidge was born on 19 August 1887 in the village of Slane, County Meath, Ireland. The eighth child of an evicted tenant-farmer, Patrick Ledwidge, he would later claim to be ‘of a family who were ever soldiers and poets’. The Ledwidges’ cottage now carries a commemorative plaque, which had originally been placed on the Slane Bridge over the River Boyne. Seamus Heaney, Ledwidge’s most eloquent champion, has said:

That the plaque appeared on the bridge first rather than the house has a certain appropriateness also, since the bridge, like the poet, was actually and symbolically placed between two Irelands. Upstream, then and now, were situated several pleasant and potent reminders of an anglicized, assimilated country: the Marquis of Conyngham’s parkland sweeping down to the artfully wooded banks of the river, the waters of the river itself pouring their delicious sheen over the weir; Slane Castle and the big house at Beauparc; the canal and the towpath – here was an Irish landscape in which a young man like Ledwidge would be as likely to play cricket (he did) as Gaelic football (which he did also). The whole scene was as composed and historical as a topographical print, and possessed the tranquil allure of the established order of nineteenth-century, post-union Ireland. Downstream, however, there were historical and prehistorical reminders of a different sort which operated as a strong counter-establishment influence in the young Ledwidge’s mind. The Boyne battlefield, the megalithic tombs at Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth, the Celtic burying ground at Rosnaree – these things were beginning to be construed as part of the mystical body of an Irish culture which had suffered mutilation and was in need of restoration.

Ledwidge’s father died when his son was four, and his widow worked constantly, cleaning houses and in the fields, to support the family until the children were grown up. Leaving school at twelve, Frank wrote his first recorded poem at sixteen. His mother had sent him to work as a grocer’s apprentice in Rathfarnham. He was desperately homesick there and one night composed ‘Behind the Closed Eye’. Its memories of home so moved him that he quit his job and walked through the dark the thirty miles to Slane, pausing to rest at each milestone along the way.

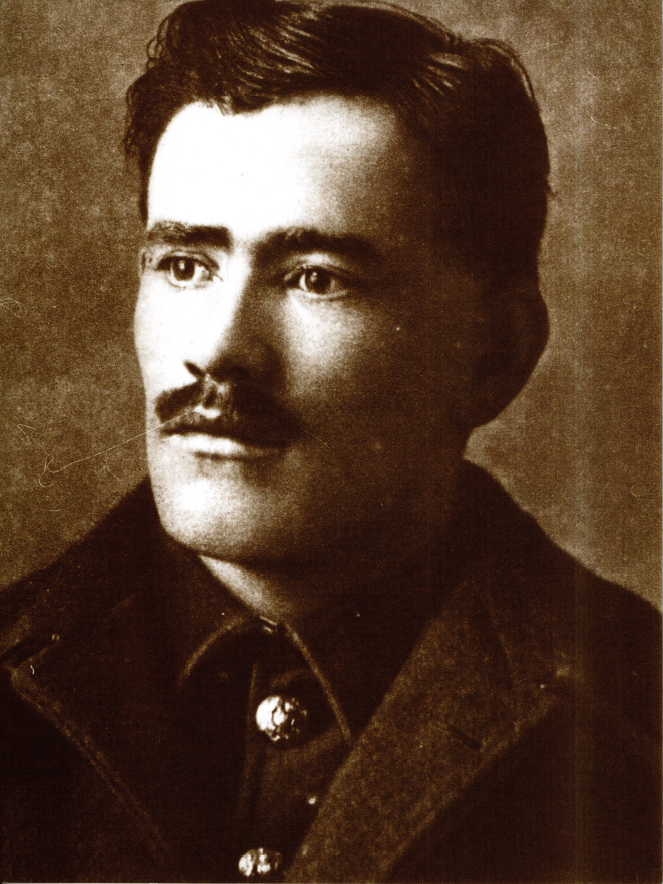

He grew into a handsome and popular young man, muscular from navvying on the roads and in the coppermines of Beaupark, a job from which he was dismissed for organizing a strike against bad working conditions. An independent, combative streak led him into fights at football matches and, later, into local prominence as a trade unionist, a member of Navan Rural Council, and, in 1914, as secretary of the Slane corps of Irish Volunteers.

His poems, meanwhile, were appearing in the Drogheda Independent and, in June 1912, he sent some to Lord Dunsany, a local landlord, himself a recognized poet of the Celtic revival. Dunsany was ‘astonished by the brilliance of that eye that had looked at the fields of Meath and seen there all the simple birds and flowers, with a vividness that made those pages like a magnifying glass, through which one looked at familiar things seen thus for the first time’. He gave Ledwidge comments and suggestions on his poems and, more importantly, introduced him to the work of such of his contemporaries as Padraic Colum, AE (George Russell), Oliver St John Gogarty, Thomas McDonagh, Katherine Tynan, James Stephens and W. B. Yeats. Under their influence, Ledwidge began to prune the archaisms and poeticisms then encumbering his poems, but he had still to find a subject more compelling than second-hand versions of pastoral.

This presented itself, painfully, on 20 September 1914 when, as Auden said of Yeats, ‘Mad Ireland hurt [him] into poetry.’ In an epoch-making speech that day at Woodenbridge, County Wicklow, John Redmond pledged the Irish Volunteers to support the British war effort ‘wherever needed’. This split the movement: the majority, possibly 150,000 men (naming themselves ‘National Volunteers’) followed Redmond; the minority of 3,000–10,000 held to the original Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB)-influenced Irish Volunteer position. Ledwidge, a nationalist but not a member of Sinn Fein, initially sided with the hard-line minority. He came under intense pressure, revealed in a transcript of a Navan Rural Council meeting in October:

MR BOWENS: The young men of Meath would be better off fighting on the fields of France for the future of Ireland. That was his opinion, and he would remark that he was sorry to see there in the town of Navan – and probably in the village of Slane where Mr Ledwidge came from – . . . a few Sinn Feiners that followed the tail end of MacNeill’s party. There was nothing but strife in the country as long as these people had anything to do with the country . . . What was England’s uprise would be also Ireland’s uprise.

Letter to his friend Matty McGoona from barracks in Dublin in 1915

[Applause]

MR LEDWIDGE: England’s uprise has always been Ireland’s downfall.

MR OWENS: . . . What was he [Mr Ledwidge]?

Was he an Irishman or a pro-German?

MR LEDWIDGE: I am an anti-German and an Irishman.

Five days later, in agony of spirit, he enlisted in Lord Dunsany’s regiment, the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. His decision may have been influenced by the news that Ellie Vaughey, the woman he loved, was to marry another man, but there is no reason to doubt his own explanation: ‘I joined the British Army because she stood between Ireland and an enemy common to our civilization and I would not have her say that she defended us while we did nothing at home but pass resolutions.’ In June 1915, when the Fifth Inniskillings were preparing to depart for Gallipoli, Ledwidge heard that Ellie had died and wrote the first of several elegies for her:

Carrying the wounded down to the jetty for transfer to hospital ships at Gallipoli

A blackbird singing

On a moss-upholstered stone,

Bluebells swinging,

Shadows wildly blown,

A song in the wood,

A ship on the sea.

The song was for you

And the ship was for me.

A blackbird singing

I hear in my troubled mind,

Bluebells swinging

I see in a distant wind

But sorrow and silence

Are the wood’s threnody

The silence for you

And the sorrow for me.

Dugout in the cliff face at Gallipoli

‘The ship’ reached Gallipoli on 6 August and Ledwidge fought from its scorching trenches until, at the end of September, the Inniskillings were transferred, first to the island of Lemnos and then to the Serbian Front. There, dug into a freezing mountain ridge and subsisting on starvation rations, he heard that his book of poems, Songs of the Field, assembled with Dunsany’s help in the peaceful summer of 1914, had been published.

Ledwidge was back in Slane on sick leave, after a punishing retreat march to Salonika, when on Easter Monday 1916 his former comrades of the Irish Volunteers, combining with units of the Citizen Army, launched the Dublin Easter Rising. It was bloodily suppressed, and Ledwidge’s feelings can be imagined when, in early May, the fifteen ring-leaders faced a firing-squad wearing the uniform he had himself elected to wear as an act of Irish patriotism. He tried to dull the pain with drink, reported late for duty, and was court-martialled for making offensive remarks to superior officers. His distress, however, was to find a more productive outlet in his ‘Lament for Thomas McDonagh’, one of three poets to face the firing-squad:

The manuscript of Ledwidge’s ‘Lament for Thomas McDonagh’

He shall not hear the bittern cry

In the wild sky, where he is lain,

Nor voices of the sweeter birds

Above the wailing of the rain.

Nor shall he know when loud March blows

Thro’ slanting snows her fanfare shrill,

Blowing to flame the golden cup

Of many an upset daffodil.

But when the Dark Cow leaves the moor,

And pastures poor with greedy weeds,

Perhaps he’ll hear her low at morn

Lifting her horn in pleasant meads.

His grief at his friend’s death, perhaps an intimation of his own (his elegy can be read as a ‘Lament’ for himself), and his guilt at what must have seemed his betrayal of the Nationalist cause, all combined to bring his pastoral vividly to life – and death; that polarity is adumbrated in the bitter-sweet (bittern . . . sweeter) overture of the opening stanza. The Easter Rising was to ‘hurt him into poetry’ more than the Great War.

April 1917 found him in action again, this time on the Western Front, from where he wrote to Edward Marsh (see p. 12), who had published him in his Georgian Poetry volumes:

If you visit the front, don’t forget to come up the line at night to watch the German rockets. They have white crests which throw a pale flame across no-man’s-land and white bursting into green and green changing into blue and blue bursting and dropping down in purple torrents. It is like the end of a beautiful world.

On 31 July, when by a cruel irony he was at work building a road through mud (as, years before, he had done in Meath), he was killed by a stray shell.

Three months later, his second book, Songs of Peace, appeared, to be followed by his Last Songs, which ends with ‘A Soldier’s Grave’ (possibly a memory of the shell-swept slopes of the Gallipoli peninsula):

Then in the lull of the midnight, gentle arms

Lifted him slowly down the slopes of death,

Lest he should hear again the mad alarms

Of battle, dying moans, and painful breath.

And where the earth was soft for flowers we made

A grave for him that he might better rest.

So, Spring shall come and leave it sweet arrayed,

And there the lark shall turn her dewy nest.

Mudros harbour, Lemnos, with the French camp in the foreground

Ledwidge had called himself a ‘poor bird-hearted singer of a day’ and, like the lark and blackbird, his song is distinctive and beautiful but narrow in its range. He speaks, nevertheless, for 200,000 of his countrymen who enlisted in the British Army – 27,000 of whom died – because they believed England ‘stood between Ireland and an enemy common to our civilization’. It is fitting that he and they should be commemorated by a greater poet, Seamus Heaney, whose elegy ‘In Memoriam Francis Ledwidge’ ends:

From a letter to Katherine Tynan from the Western Front

I think of you in your Tommy’s uniform,

A haunted Catholic face, pallid and brave,

Ghosting the trenches like a bloom of hawthorn

Or silence cored from a Boyne passage-grave.

It’s summer, nineteen-fifteen. I see the girl

My aunt was then, herding on the long acre.

Behind a low bush in the Dardanelles

You suck stones to make your dry mouth water.

It’s nineteen–seventeen. She still herds cows

But a big strafe puts the candles out in Ypres:

‘My soul is by the Boyne, cutting new meadows . . .

My country wears her confirmation dress.’

‘To be called a British soldier while my country

Has no place among nations . . .’ You were rent

By shrapnel six weeks later. ‘I am sorry

That party politics should divide our tents.’

In you, our dead enigma, all the strains

Criss-cross in useless equilibrium

And as the wind tunes through this vigilant bronze

I hear again the sure confusing drum

You followed from Boyne water to the Balkans

But miss the twilit note your flute should sound.

You were not keyed or pitched like these true-blue ones

Though all of you consort now underground.

Night scene in the trenches, Western Front, 1916

Darkness and I are one, and wind

And nagging thunder, brothers all.

My mother was a storm. I call

And shorten your way with speed to me.

I am love and Hate and the terrible mind

Of vicious gods, but more am I,

I am the pride in the lover’s eye,

I am the epic of the sea.

1916

Beside the lake of Doiran

I watched the night fade, star by star,

And sudden glories of the dawn

Shine on the muddy ranks of war.

All night my dreams of that fair band

Were full of Ireland’s old regret,

And when the morning filled the sky

I wondered could we save her yet.

Far up the cloudy hills, the roads

Wound wearily into the morn.

I only saw with inner eye

A poor old woman all forlorn.

1916

Kiss the maid and pass her round,

Lips like hers were made for many.

Our loves are far from us to-night,

But these red lips are sweet as any.

Let no empty glass be seen

Aloof from our good table’s sparkle,

At the acme of our cheer

Here are francs to keep the circle.

They are far who miss us most –

Sip and kiss – how well we love them,

Battling through the world to keep

Their hearts at peace, their God above them.

1916

A broad field at a wood’s high end,

Daylight out and the stars half lit,

And let the dark-winged bat go flit

About the river’s wide blue bend.

But thoughts of someone once a friend

Shall be calling loud thro’ the hills of Time.

Wide is the back-door of the Past

And I shall be leaving the slated town.

But no, the rain will be slanting brown

And large drops chasing the small ones fast

Down the wide pane, for a cloud was cast

On youth when he started the world to climb.

There won’t be song, for song has died.

There won’t be flowers for the flowers are done.

I shall see the red of a large cold sun

Wash down on the slow blue tide,

Where the noiseless deep fish glide

In the dark wet shade of the heavy lime.

1916

The silence of maternal hills

Is round me in my evening dreams,

And round me music-making bills

And mingling waves of pastoral streams.

Whatever way I turn I find

The path is old unto me still.

The hills of home are in my mind,

And there I wander as I will.

1916

My mind is not my mind, therefore

I take no heed of what men say,

I lived ten thousands years before

God cursed the town of Nineveh.

The Present is a dream I see

Of horror and loud sufferings,

At dawn a bird will waken me

Unto my place among the kings.

And though men called me a vile name,

And all my dream companions gone,

‘Tis I the soldier bears the shame,

Not I the king of Babylon.

1916

Where Aegean cliffs with bristling menace front

The threatening splendour of that isley sea

Lighted by Troy’s last shadow, where the first

Hero kept watch and the last Mystery

Shook with dark thunder, hark the battle brunt!

A nation speaks, old Silences are burst.

Neither for lust of glory nor new throne

This thunder and this lightning of our wrath

Waken these frantic echoes, not for these

Our Cross with England’s mingle, to be blown

On Mammon’s threshold; we but war when war

Serves Liberty and Justice, Love and Peace.

Who said that such an emprise could be vain?

Were they not one with Christ Who strove and died?

Let Ireland weep but not for sorrow. Weep

That by her sons a land is sanctified

For Christ Arisen, and angels once again

Come back like exile birds to guard their sleep.

1917