He carried a chair into the empty basement bedroom, tipped the hatch to close it, and sat down near the door. He waited in the dark and watched the floor.

After a while, the warm closeness of the room overcame him and he drowsed, filling the darkness with dreamy, elongated shapes. He imagined that any action was a possibility—that was what the crèche meant—there was no limit on behavior, absolutely everything was happening all of the time and he was simply a line of awareness trickling through the densely packed matrix of probability, his life an infinitesimal silvery trace, all but invisible within the morbid certainty of endless variation.

At the noise of carpet slipping against carpet he came alert. The square of floor, lit from below, lifted and then turned on one end, lighting the room. Kim’s hand appeared first, flat on the carpet, the edge of the white robe sliding back from her wrist, and then her head rose out of the light.

She saw him and her mouth opened—an O of surprise. Her face hardened and she stared at him with open hostility as she climbed the rest of the way out of the floor.

“You lied to me. You said you didn’t come down here more than once a week,” she said.

“You remember that.”

Her mouth tightened and she walked calmly past him. He rose and followed her into the small bedroom where she had flicked on the light and was pulling her black travel bag out from under the bed. He hadn’t looked under the bed.

“Do you want to talk about what happened in there?” he asked, as she began laying her clothes out on the bed.

She shook her head No.

“Did you tell Laughlin you were sick, or . . .” He let the question trail off.

“Laughlin?” she asked.

“Your boss.”

“Work is fine. I’m on sick leave.” She pulled on her underwear and was putting on her bra.

“How long have you been doing this?”

No answer.

“How many Kims have I been sleeping with?”

“How would I know? More than one I guess.”

“Alright. And, are—whoever you are now—what kind of work do you do?” he asked. “Are you a politician, or a janitor, or do you own a jewelry store, or a restaurant, or are you a short order cook, a waitress? What . . . what do you do for a living, Kim? Is that your name?”

“I’m the same person who left,” she said, pulling on her jeans. “Nobody died while I was gone.”

“Or came back to life? You’re sure of that?”

“No, I’m not sure,” she said while she was pulling on her green blouse. “How’s Bill, Vin?”

“Don’t pretend it’s not reasonable for me to ask questions.”

“I’m the same person I was yesterday.”

“What’s the name of our daughter?” he asked, and she froze, her fingers stilled at the bottom button of her blouse.

“What’s the name of our daughter?” he asked again, his voice rising.

“The name—”

“The name.”

“She’s alive?”

Her head came up, her desperation a goad to the rage that filled him. Wherever she had come from, it had been less than this universe, less than what he and Kim had made here. In her world, Trina must have been miscarried. She had never happened. He held himself motionless, but the room blanked to red.

“Vin,” she said, pleading. “You’re not just saying that. Trina’s alive?”

Which surprised him. She knew their daughter’s name. She wouldn’t if Trina hadn’t been born in her world. She wasn’t responding as he expected. This wasn’t what he thought it should be.

She ran past him, barefoot, and slammed open the apartment door so it bounced against the wall. He shook off his astonishment and followed. By the time he reached the porch she’d already thrown the door open and was shouting—“Trina! Trina!”—her voice rising through the house.

Then she was rushing up the stairs, jumping two and three at a time, still yelling Trina’s name. He chased her to the second floor where the yelling stopped. Kim had fallen to her knees in Trina’s room. She buried her face in the neatly made bed and stretched out her arms and grabbed the blankets and pulled them toward her as she gasped and breathed in the scent on the sheets, the smell of their daughter.

Vin watched as her burst of energy decayed into sobbing. She climbed onto the bed and curled up in the blankets, crying. After a long time, when Kim was lying still on the bed, her eyes open, shocked and staring, he said softly, “What happened? What happened to you?”

Kim said, “Where is she?”

“She’s at daycare.”

Kim’s voice became cold, quiet and firm. “I want a divorce, Vin. I’m taking Trina.”

He rocked backward as if struck. He staggered, turned slowly away from her. He descended the stairs and sat at the dining room table, waiting for her to come down.

Her world and his could have been misjoined in any number of places. Anything could have been happening in her mind. He needed to consider the best way to talk with her about what she thought was happening.

He listened to her moving upstairs but she climbed to the third floor and there was quiet. With a spike of adrenaline, he remembered he had left the door to the apartment open. He went outside and around the house. The door was wide open, exposing the empty living room. He stepped in and closed it.

The hatch in the bedroom had closed so he stepped on the switch and it lifted. “Mona!” he called down, which didn’t make sense if Mona was in a casket.

“Vin,” she said softly, from behind him.

He spun, taking one short step backward, his heel landing on air, toe scraping the lip of the chute. Momentum from the spin carried him sideways into the hatch. He fell, bouncing against the side of the chute, fumbling to keep from dropping down it, then his leg exploded with pain as he lost consciousness.

When he became aware again, he was on his side at the edge of the chute but looking at the ceiling, his leg somehow both in agony and numb. He felt as though he was drowning in air. Mona’s head came in sight, blurry and partial. The planets were actors and the moon was saying, “That’s your cue.” And then Mona disappeared and Vin blacked out again.

He reawakened in an ambulance, and again in a hospital room. He tried to imagine that the day had not happened.

His leg wasn’t broken, but both his knee and hip were badly twisted. Kim didn’t respond to his calls and texts. He got an email that said she was sorry he was hurt. She said Trina was fine. The email included an apology and a link to the web page of a divorce attorney.

He had a phone call from his mother in Michigan. Kim had told her he was hurt and that they were getting a divorce. He had difficulty listening and was almost unable to respond through the fog of his anger. The next day, he got email from his brother, expressing concern.

John Grassler and Corey Nahabedian showed up the next evening to help him get home. John said he was sorry to hear that things were difficult between him and Kim.

Sophie still had food and water. Vin asked Corey to check if the door of the basement apartment was locked and Corey confirmed that it was. Vin had no idea where Mona had gone off to, and couldn’t descend the chute to look. No one answered the walkie-talkie.

Because there was no one else in his home, a home health aid was assigned to check on him daily. The aid was a tall, thin man with a protuberant Adam’s apple and an unhurried demeanor that frustrated Vin. He said he’d get Vin back on his feet and actually winked as he said it.

Trina texted every day from Kim’s phone, a few words or an emoji or two, always preceded by “from Trina.” Sometimes a few came on the same day. He replied every time, ignoring the fact that Kim must have been helping; just trying to tell Trina how much he loved her. He waited for texts throughout long, dry, day-lit hours while he was trying to read, or was staring at the water outside the picture window, or lying awake on the big sectional that the health aid had dressed as a bed.

He had no desire to work. He called Kim and alternately begged and threatened her, leaving a catalog of voicemails because she never answered his calls.

He was in a dream, standing on the sidewalk in front of a coffee shop, Caffé Vita on lower Queen Anne. There was a crèche inside, three caskets near the door to the restroom. He wanted to go inside but a man blocked his way.

The man’s hair was tangled and greasy, his mouth loose, his lips sliding over crenellated teeth. He wore black jeans and a black T-shirt and his eyes were bright and sharp.

“I’m the old stag,” the man said with cryptic dignity, extending his hand.

“My name’s Vin.”

“Oh, I know you Bambi,” said the man, “but your name doesn’t matter. I’m Buck, the old stag. I’m here to show you the ropes.”

Vin reached to shake his hand but as soon as they touched the man pulled back and rubbed his palm on his faded jeans, as if rubbing off the contact.

“Psyche,” he mumbled.

“My name’s Vin,” Vin said again, pointlessly. “What should I call you?”

“Buck. And devil take the hindmost. Ha.”

Then they were on Aloha street trying to merge south onto State Route 99, but they were on foot, not driving.

“JFC!” Buck yelled in frustration because he couldn’t get into traffic safely.

“What?” Vin asked.

Buck glanced at Vin and his upper lip rose, almost a snarl. Then his face relaxed and he appeared thoughtful.

“What I mean is,” he said, “it’s simple, like ABC.”

But Vin thought those weren’t the letters he had heard. Buck was ignoring him now. Cars flew past on the highway. Buck’s head jerked, his top lip and nose wrinkled upward as he drew in a breath. He leaned toward Vin. “The machines of the mind are more difficult to recognize than machines of iron and steam.”

They walked back to Caffé Vita but not by a route Vin knew. They were moving silently, disturbing nothing. People didn’t notice them. Birds and sunlight filtered through high treetops. Vin had a sense that the two of them were being stealthy and that all the small animals just out of sight were unaware of their passage.

High, layered apartment buildings rose on either side, and the street had gaps that descended to other levels of street. Their path reminded Vin of a place he once walked in Lisbon, on his way to a movie theater.

“What are you crying about?” Buck demanded, which felt unjust because Vin wasn’t crying.

“How can I get back to where I want to be?” Vin asked.

“No telling.” Buck was sipping his latte in a booth at Caffé Vita. His face had a greenish pallor. “But in my experience, among the available infinities, there’s always a higher proportion with you than without you, so odds are you’ll find yourself again.”

The health aid stopped visiting, which was just as well. Vin’s cheek had started twitching when the man winked at him. Vin’s doctor told him that he’d always limp. And then, in a moment when he was at the picture window wondering how many days in a row the sky had been blanketed by dark gray clouds, everything cheerful about the world disappeared. It only took an instant. Words became flayed skins of sound, meaning drained.

From that moment, Sophie stopped coming to him. She eyed him from a distance. He had stopped feeding her at regular intervals and now she stopped protesting.

He no longer saw a reason to turn on the lights in the house. He realized he had never really thought much about them. Maybe Kim had been turning them on and off when she lived with him. The city remained weather-stricken. He closed the curtains and lived in the dark.

He spent hours planning to regain custody of Trina, working through scenarios. Kidnapping was appealing, but as he thought it through, it was difficult to escape the high potential for catastrophic failure, if a neighbor happened by and got nosy at the wrong time, or if Trina chose the wrong moment to scream or run. No matter how he went about it, kidnapping would require a lot of advance work, scouting, and thorough planning, which also added risk. Another possibility that might be less risky was destroying Kim’s reputation, after which he could appeal the custody agreement. There were reasonably secure ways to do that, starting online. He could connect her with unspeakable services. She would have to click a couple of links to make it all work, but he knew enough about her to hide the links in things that looked innocuous. Then he’d adopt aliases to build out a record of activity that he could accuse her of in court. He could even make pictures of her doing things, and forge browsing records. And he knew where to go for advice—the Internet was almost a push-button operation for harassment. And he could attack her finances. He probably still had enough information for that. Or hire someone to force-feed her Fentanyl. He did many long hours of research on the dark web. There were people who could help. But maybe Fentanyl was too elaborate. Simpler would be safer.

The big problem, however, that he kept running into as he gamed out his ideas was that they always ended with him being an unfit parent. And if he were unfit, that would mean that Kim had been right to take Trina from him. When he reached this point, he would start over with a new idea.

He would sometimes piece together enough resolve to phone a friend and beg for news about Kim, but he stopped making those calls because he kept threatening his friends when he thought they were withholding information. He started sending emails to Kim describing how wrong and unfair she was being, and then warning of consequences if he didn’t get custody of Trina. It felt important to describe the consequences in detail. He got an email from an attorney who claimed to represent her and who asked for contact information for his attorney. He wrote that he was not going to hire an attorney but was avidly looking for an assassin.

John and Corey dropped by a few times. Vin tried hard not to lose his temper with them. One of them would sometimes accompany him on a short walk with the crutches. Weeks passed. On the day he finished with the crutches, he received a call from his new manager at work, who told him his projects had been picked up by other developers. When he was ready to come back, they’d review his options.

“Am I fired?” he asked.

“We’re not saying that,” said his new manager, with warm imprecision. Vin didn’t mind.

When divorce documents arrived, they included references to threatening voicemails and emails. He didn’t recognize most of the quotes but when he checked his Sent Messages, he saw they were accurate. The elaborate language he’d used surprised him and he couldn’t bear to read it all. Life felt alien and he was unrecognizable to himself.

Kim wanted full custody and the right to determine when he could see Trina. She made no claim to any joint assets, including the house. The documents included a note that Trina had written saying she wanted to live with her mother because she was scared of him. He lay down on the sectional and didn’t move for the rest of the day.

He had locked infinity in a vault in their basement and it had exploded into Kim’s life, and then her life destroyed his. He didn’t know whose fault it was, but what they were suffering had to end. The day after he received the documents, he found an inexpensive attorney and signed everything.

Two days after the divorce was finalized, as he was idly scanning job ads, his phone rang. It was Kim. “Vin,” she said when he answered—she was crying—“I had to do it because I know what you’re capable of. I’m sorry. I’m sorry, but you need help.”

“You never trusted me. I don’t know you,” he said, feeling clearheaded, “and you don’t know me. You’re a stranger who’s living in my ex-wife’s body. One day, I’ll come for my daughter. You shouldn’t get in my way. Don’t call me again.”

“Vin,” she said, panicked, “I know what you’re thinking. I know. Don’t do it, please. We didn’t love each other. We really just didn’t. Vin, we were only together, weren’t we, because of what happened with Bill? And yes, I did this. I did. But I was thinking about you, too. I thought, maybe there was a chance if I went into it, then—I thought someone else might come out, someone who could really love you, and forgive you. But I got so lost. I saw things . . . I went through hell.” Kim sobbed softly as Vin waited in a wash of confusion. “I was trying to find her. When I realized I’d come to a world where Trina was still alive—”

“What do you mean, goddamnit,”—he shouted, blowing out his voice—“why the hell are you saying that? What happened to my daughter in your fucking, shitty world?”

There was only the sound of breath from four lungs, two throats, two mouths, breath finding its way between worlds. Kim said, “Oh, Vin, you have to know. You can’t guess what happened?”

“No. How the hell would I be able to do that? You weren’t here. I was here. The whole time. You were someplace else. Somewhere else.” He shouted again, the last phrase.

“No, it was all the same. Everything is exactly the same as here. But, where I started, we had a party, and, a man came. He was a military, army or—anyway, he was wearing a gun, and he was yelling. I think he was looking for Nerdean, her office. You got angry at him.” Kim cried softly for a few moments. “You got so angry. I watched and I couldn’t stop it. You started a fight but he had a gun. And he shot Hanna. She was okay. But—Trina . . .” And she couldn’t say any more.

Into darkness and distance—through the space a phone line crosses that is filled with every possibility that never happens—Vin strained to hear more. Anything that might start on the other side of that gap but would come from a world he recognized.

“No, Kim,” he said at last, “that’s not right. That didn’t happen.”

“It did.”

“No, it didn’t. You’re confused. That’s what happened with your brother, Bill. That’s what happened to you and to him. But it didn’t happen here. Trina didn’t die.”

“I know. I know it.” She said, and hung up.

The law is a frosting of cyanide and judges are bitter, small people, angered by their humiliating yoke of stunted ambition, drunk with their smeary quarter-ounce of power. Lawyers look at you and see a meal. Judges see another measure of the drug that feeds their habit. No one saw him. The world he had believed in had tried to poison and kill him and sell off the parts. She had become evil. How could he have behaved differently than he did?

Kim. That was her name. But it wasn’t her. She had taken herself away from him. Whoever this woman was, he didn’t know her.

Before this, Bill was the person he had relied on. They could talk about anything. But this “Kim” was here now instead of Bill.

He could learn to murder safely—a poison that broke down completely or a neatly staged accident. Make it look like suicide. Who would investigate a death if it clearly looked like suicide? Who would really do that? And what if she died in an underfunded county in some bankrupt state where working people are shitty at what they do? He could plan that out, make that happen. He was patient. He was good at fine detail work. He knew how to use log-less proxy services to hide activity online. He knew how to scrub a hard disk to make it truly unreadable and then how to drill it and smash it.

And if things went wrong? He could escape through the crèche. It was the perfect safety valve. Someone else would land in the problems he created. Did he care about that? That one other person?

Although, if the crèche was what he thought, he would be creating the same situation an infinite number of times—infinite variations across infinite worlds. But, if Mona was right, that problem already existed.

He could just use the crèche to leave. Find another world. Was there such a thing as a better world? He could find a place to be with his daughter. He was a good person who had gotten lost among infinite possible worlds.

The crèche was an alternative to staying in this universe and finding out what he would do. And among the infinite possibilities there must be at least a single world in which Kim loved him. It had to have been possible for her to love him.

Mona was gone. She had walked out of the apartment into the physical world and disappeared. The office was his now. The house was empty. All the caskets were empty. The dead had risen.

He sometimes woke in early morning hours without his anger and lay like a stain in the bed that possessed the memory of Kim’s body. In that other world, the one that the present had deprived him of, her arms and legs had stretched out beside him and he would brush against them and gently lean into the smooth warmth of her skin, igniting and intensifying their delicate radius of safety. Now he turned from side to side in the densest darkness or lay on his back keeping his eyes closed and the house sometimes creaked or popped as houses do and he was seared with the useless hope that the sound might be Kim or even Trina—a footstep, an inadvertent bump—one or the other of them out there, near him, one or both returning.

Nerdeanisreal—the files on the systems in Nerdean’s office were completely different when you logged in with that password. The Nerdeanisreal account was the administrative account for everything in the Neardeanisafake account, so you could see and edit all of the Nerdeanisafake material, and a great deal more.

It occurred to Vin that there might be other accounts, so he logged out and tried to log back in with several other passwords:

Nerdeanisanasshole

WhatthefuckNerdean?

ShitfuckshitfuckshitfuckNerdean

FuckyouNerdean

Nerdeanistheabsolutelycruelestfuckeronthisicymotherfuckingplanetofhell

Nerdean?Hello!Nerdean?, and a few more. None worked.

When he tired of pounding out frustrations on the keyboard, he read further into the new documents, the truer explanations. The files under this account assured him that time and chance were both—as Mona had said—illusory. Everything that had or could exist always did. The human experience of life was the result of a kind of channel created by and filled with awareness. The mind moved; the world didn’t. The mind’s path formed as the alchemy of observation slipped through the unimaginably vast and otherwise static structure of everything, the mind trickling, ever in motion, pulled toward states of greater entropy.

Sure, I’ll buy that for a dollar, Vin thought. Why the fuck not? He logged off. He sat in the eggshell chair looking at the dark screen and imagining Kim there. He imagined Kim reading that same drivel before giving in to her weak, frustrated, middle-class despair and then throwing all of their fucking goddamn lives onto the bonfire of pure chance.

Although—and here he dynamited the roaring train of his own furious musings—she did that only after he had done the same thing. And after he had done it a few times. And then told her about it. And admitted to her that he was sometimes tempted to do it again.

But she had always been so frustrating in that way, always drawn toward the things that frightened her.

And so, if he knew she was always that way, shouldn’t he have been able to recognize the risk? How much of her had he missed? Did he know her at all, or had he just been filling in an outline with his own ideas? (And if ideas were things a person could contain, could the crèche measure them?)

As for lucid dreaming, the new files only referenced it in a passage that said the crèche was so revolutionary that its capabilities should be disclosed slowly, or new subjects might be too frightened to test its full potential. Vin had difficulty wrapping his mind around the savage arrogance that passage betrayed. Its author was willing to camouflage the nature of the device, hide its ability to wreak havoc on a life. And for what? To experiment?

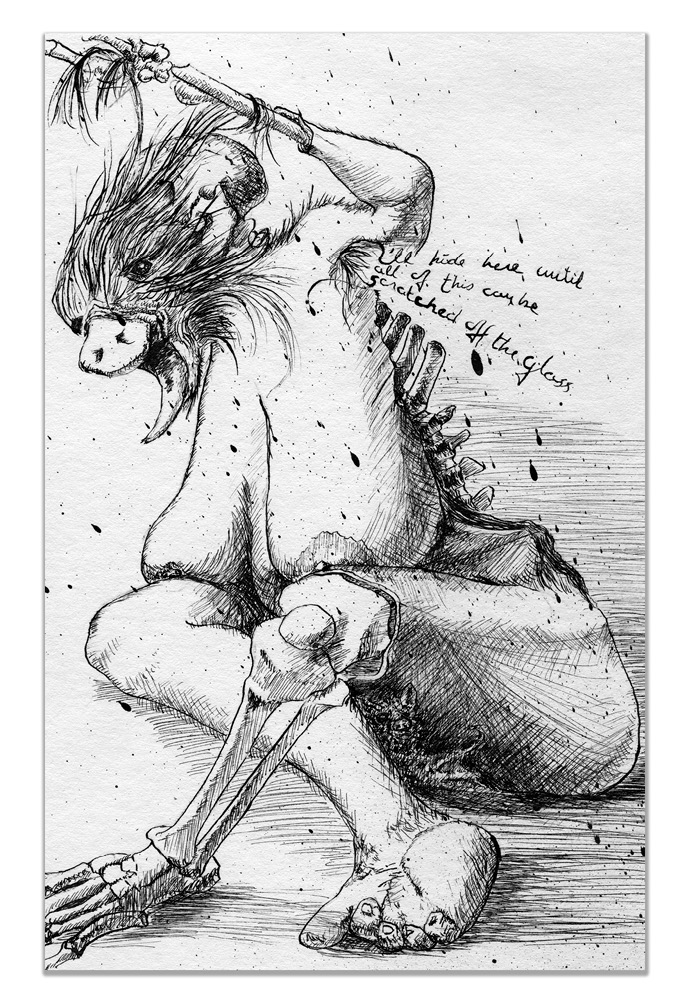

Also surprisingly, this “truer” documentation contained only a small number of well-constructed, coherent passages. Most of it was a jumble of mannered terminology, excess, and slapdash notes sprawling under hoary titles like, “The Second Law of Thermodynamics and Attributes of the Structural Relationship Between Event Contexts that the Human Mind Interprets as Probability.” It also included many obscene drawings of massive genitalia variously configured with faces, brains, and deformed bodies. They looked as though they were drawn on paper, scanned, and then pasted into the files. Beneath many were neat, numbered captions—like “Mind Fuck Series”—as if they were items in a formal display. They seemed to be interspersed without a pattern throughout the files, their creator ensuring a record of comprehensive disdain.

A file titled “Exercising Causality Through a Surrogate Awareness” had a tutorial on how the “subject,” a person in a crèche, could influence the actions of a “surrogate,” a person whose mind the crèche was “compositing”:

The subject may only directly affect the surrogate’s internal dialog . . . Broadly speaking, the subject has two options for taking action:

1) develop trust over time by aligning with a surrogate’s perceived self-interest. The subject becomes a trusted advisor to the surrogate . . .

2) Bombard the surrogate with hyperbolic emotional messages, either strongly positive or strongly negative. Sudden, unexpected shifts from one extreme to another can enhance this approach, which may generate emotional disruption intense enough to interrupt the surrogate’s motor response system, thereby creating opportunities to exercise direct control.

It went on. There was nothing about whether the techniques should or should not be used, only how to use them.

A large document named “Unforeseen Risks” began: “Original assumptions were that the crèche technology was essentially risk free. Subsequent extrapolation from empirical results suggest the following list of possible risks.” And then a long list of nightmarish scenarios, such as:

4) Double-Loading: New probability models predict an unmeasurable possibility that two affiliated awarenesses may be simultaneously recalled to the same body, creating a highly volatile and possibly lethal encrustation of pre-explanatory awareness.

There was no explanation of what “pre-explanatory awareness” might mean, and:

9) Shot-Stuck: a process by which a subject becomes immune to the potential for a return shot. This risk has been confirmed, but is probably highly improbable.

At the end of the list, he added:

Maybe Nerdean is an unhinged sadist and anything is possible.

Vin learned that aiming of the outbound shot was very crude. Because all constraints bracket infinite possibilities, the initial “throw” of a mind from the device was less “aimed,” and more “guided”—almost random, no matter what parameters were set. The “return throw,” on the other hand, had a clear target: a crèche. “There are infinite possibilities for the return, but all include a crèche prepared to receive a specific mind.

“The crèche terminates a shot by collapsing the field that sustains dislocation of the subject’s basis (his or her awareness). Acute local perturbation in the field of consciousness resolves and consciousness reinvests the subject. However, any motion of a basis requires a transition through a probability state, including the inescapable influence of all entropy (necessary uncertainty) attached to relevant contexts. Entropy ensures an incongruity between the basis and the subject. Put plainly, there is infinite likelihood that a ‘person’ will not return to their originating body.”