Do You Need a Moment?

They sat at the card table, open cartons of Thai takeout spilling onto the paper plates. Bill was still a sloppy eater. Vin had finally been able to keep something down—a little tofu Pad See Ew because, despite his leather jacket, Bill was inexplicably vegetarian. Vin was nursing a beer.

Bill said, “I think about this sometimes, how I could have been born as anyone else. But then, I think, everyone feels like they’re dealing with a load of terrible shit, so all things considered, things could be worse.”

“No, you couldn’t really be anyone else. Your body, your specific relationship to time and space makes you who you are. You’re bound to your circumstances.”

“Alright, man. That’s a lot more literal than I was taking it.” Bill poked through the wide noodles before spearing a chunk of tofu. “You know, without that stuff in the basement, none of your story would be even remotely believable.”

“Yeah.”

Bill stared at him and grinned.

Vin laughed. “You know, you’re better here.”

Bill’s smile began to fall away. “Meaning what?” he asked. “Better how?”

“Well, just . . .” He looked down at the food cartons.

“Oh.”

“How did you do it?”

“Stay sober? You’re asking me . . . What I want to know is why I didn’t get sober in your other world.”

“I don’t know—you kept trying things. Maybe something happened there, or you were more broken, or . . .”

“Wow. I’ve never felt so good about being an addict in recovery before.”

Vin was looking at the stained mess of food on his plate again. He couldn’t look at Bill.

“Okay,” Bill said. “Well, I’m still finding it hard to believe in travel between dimensions, no matter how many DIY home dungeon recipes you followed out of your old Maker magazines.”

Vin laughed. “You’re more sarcastic here.”

Bill set down his chopsticks. “So, in this other world, Kim was alive?”

“Yeah.”

“But, I was dead?”

Vin nodded.

Bill shifted in his chair. “And you married her?”

“Yeah, but she was unhappy.”

“You didn’t make it?”

“I tried. I don’t know what it’s like between you and Peg. I thought everyone must be a little unhappy, you know? She didn’t think we really knew each other.” Vin listened to the quiet in the room. “We both felt guilty about you. I didn’t see how important that was. Just how hard it was on her. I—”

Bill started up but then slumped back into his chair and closed his eyes. “Yeah.”

The room was quiet, the big house empty and haunted as though only desire could live in it and only alone. Bill said, “You’re right, though. I mean, I killed her.”

Vin couldn’t look at him.

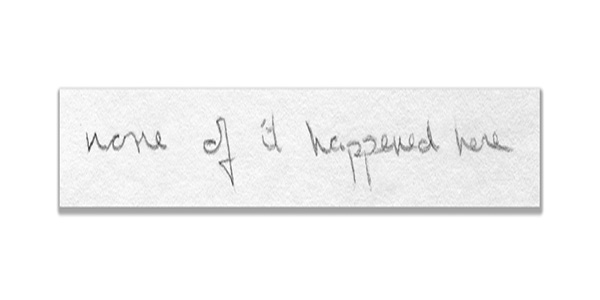

“But, you’re from another world. And there are worlds where it didn’t happen. That’s how it breaks down, what you’re saying. I just got myself into a shitty one.”

Vin lifted his beer but didn’t want to drink. He set it on his knee. “This world doesn’t seem shitty.”

“What happened,” Bill asked, “in the other world? How did I save her?”

“I don’t know what happened here . . .” Vin hesitated, then told him the whole story. When he was done, Bill said, “Your phone was dead. You said you didn’t charge it.”

“It could have gone any other way,” Vin said.

Bill stood, looking around as if unsure where to go. “To be clear, in every world, in every other world you went to, I was an alcoholic and a drug abuser?”

“Yes,” Vin said, seeing the terrible weight of the word as it pressed Bill.

Bill turned his head, but wasn’t looking at anything in particular. “Yeah. I was going to ask whether maybe I could use that thing. But what you’re saying is, what’s the point, right?”

“I don’t know. Everything that’s possible happens.”

“So you said. Look, I’m glad you called. It’s always good to talk, man. And I want to find out more about this. All of it. You’ve been there for me, I know, and I almost believe you. Batshit crazy. But, right now, I think I should call my sponsor, so I’m going to leave. I’ll call you back and we’ll talk again, okay? Alright? I’m going to go.”

“Bill, you can’t tell him about this. Your sponsor. I’m not telling anyone. Goddamnit, I’m so sorry. Bill, this stuff can’t be known.” When Bill stared at him, Vin said, “Nerdean didn’t make it public. She didn’t want people to know about it.”

“And who is Nerdean? And why should I care?”

They looked at each other. This version of Bill was very different. Less afraid. “Okay,” said Vin. “I’m the one who’s not ready to make this public. Yet.”

That night, as he lay awake on the air mattress and felt the bellows of his chest manufacturing moments, he imagined a crèche that would allow a person to simply sleep, to pass decades of life dreaming peacefully while the world changed outside the box. Maybe there were worlds in which he was the one who died, rather than Bill or Kim. In those worlds, someone else might have found the crèche.

He needed to confront the question he had been avoiding: what next? He was restless. He rose and dug in the closet for a change of clothes, discovering a small safe hidden inside a cabinet. It looked like the same safe he’d had in the master bedroom when he was living in the house with Kim and Trina. He tried his combination and it opened, revealing a small, bright chamber that contained five thousand dollars in cash, his .38 caliber handgun, some design documents and a shoulder holster.

He called out for Sophie but she didn’t respond and he didn’t hear her moving in the house. She sometimes slept on an afghan near the television but he didn’t remember if the afghan was in this version of the house. He decided to look for her. When he got downstairs, a thin woman with iron-gray hair was sitting at the card table. She appeared to be waiting for him. She was wearing a T-shirt and what looked like a pair of his jeans. They were baggy on her. She’d strung a sheet or pillowcase through the belt loops to keep them up on her spindly frame.

It was the woman who had been in the crèche the first time he saw it, years ago, in a version of the house very much like this one. She smiled, her teeth perfect despite her apparent frailty.

“Sit still and go far,” she said, her voice crackly and high.

“Nerdean,” he said.

“No,” said the woman, suddenly agitated, her smile disappearing, brows coming together. “I don’t know her.”

She might have been in her midthirties, her skin clear but with deep lines. The gray in her hair looked premature. She watched him with birdlike wariness, her eyes tracking him, her head twitching to align with her drifting gaze.

“You’re not Nerdean?”

“No.” She moved her head back and forth in an exaggerated, slow negation.

“Would you like something to eat? Or, some water?”

She nodded, another exaggerated motion. He went to the kitchen, trying to keep an eye on her.

“You’ve been traveling a lot,” he said.

“Yes. She gave up on faster-than-light travel and started working on weirder-than-light travel.”

“Who?”

“I would have thought my goal would be obvious,” she said. “I want to live horizontally in time.”

“Is that possible?”

“Move between universes with the changing increment of time’s most meager fragment, from universe to universe at the governing rate of change.” Her voice creaked like floorboards. “My awareness would ride the wave, the transition out of one single unit of time, one moment to the next, ride that ripple of time through eternity and travel forever in a single moment. I would live sideways through infinite lives, live forever without becoming older, live forever an infinite number of times.”

“Did you?” he asked.

The woman smiled, a mysterious, empty expression.

“I’ve been in your mind,” she said. “Remember?”

“Yes. The words that came to me.” He ran a glass under the tap. “You told me, ‘The switch will be in an appliance.’ I saw those words in my mind.”

She looked pleased and almost shy, as if he embarrassed her with praise.

“I do remember,” he said, and thought about several other times when strange ideas had appeared in his mind. He had some trouble turning off the tap. It might need maintenance.

“Good,” she said. “You’re going to see Kim again. And Trina. Everyone.”

“Nerdean,” he said.

“No. Never. I’m not that person. I’m everything that can be made from starlight.”

She stood, lifting her arms, her smile lengthening and the room behind her darkening. “I’m not Nerdean.”

The house shook. An earthquake. He’d lived in fear of one for decades. He tried to set the glass down but it fell into the sink and shattered. He reached out to keep his balance and grabbed the refrigerator door, pulling it open. A few containers dropped out, then a few more fluttered from the top shelves as the house continued to shake. The fluttering things became dollar bills and even more fell out, and then coins as well, a stream, a river, a torrent of money.

He took a step backward as a wave of clear plastic containers, the kind meant for leftovers, followed the money. They clattered onto the floor and more money poured out between them. Each container was filled with meat, red and bloody, and he saw fingers and pieces of limbs through the plastic, the butchered bits of people he loved.

“Look over here,” the woman said. Vin looked up from the piles of things and saw the wall and the picture window it contained disappear. Night sky and stars drifted behind her.

“You think this is a dream, don’t you?” she said.

He woke up. He was in his inflatable bed on the second floor. He lay still. The house had stopped shaking. He was at the tail end of a mild temblor. His bed was getting softer, the air mattress slowly deflating. So much air had gone out now that the edges of the bed began to curl over his arms and legs, covering them and then binding them so he couldn’t move. He strained to pull himself free, his teeth grinding, until he finally did. And he woke again.

But he still couldn’t move his limbs. He was still far under the surface of sleep, held down by a force that pressed on him, a weight that felt endless. He pushed against it, tried to rise, to cross the heavy layers of dream and rise above the plane of sleep. He woke again, and woke again, each time forcing himself up further, again and again and again.

He woke a final time out of a series of dreams that had filled him with euphoria, dreams that had showed him days and events that seemed possible, things that might have happened in this world but that he hadn’t experienced. It was Saturday. Rattled and tired, he lay in bed until his mind ticked over to thinking about being rich. He considered finding the place where he actually lived—Bill had mentioned a condo on South Lake Union. But everything he needed was in the house and it all seemed well worn. As he fed Sophie, he wondered whether the person who had made his life in this world had spent much time at the condo.

He took a long walk through the Uptown neighborhood, stopping for a sleepy meal at the Mecca, a bar and diner with a twenty-four-hour breakfast menu where he ate waffles and hash browns under the motto, Alcoholics serving alcoholics since 1929.

Things were as he remembered them—the concrete—and plank-covered Counterbalance Park that sprang to unexpected life at night when its LED lights raised colored curtains along gray concrete walls; the orange logo of the coffee shop; the movie marquee above the pet food store that was across the street from the marquee above the old cinema; the Greek, Thai, Japanese, Mexican, and Indian restaurants; the old world pub, the pizza place. He stepped into the used bookstore and browsed, sampling paragraphs.

He took a circuitous route back to the house, climbing the wooden staircase above the tennis courts and realizing that the thing he appreciated most wasn’t the odd new awareness of being wealthy, or the feeling of knowing the place well; it was the place itself—the air, the slope of the hill, the trees he was passing that may have been different than those he’d passed on other days but which looked similar enough. The phenomenal world and its reliable consequences were all here, slowly transforming in obedience to mysterious fundamentals but offering the familiar cool breeze, the generous leafy canopies and limpid sunlight even among the infinite possibilities that branched endlessly away from each choice, each action.

In this world, Sigmoto had worked. He had stayed on as a technical lead. Rather than fighting to keep his job as CEO, the version of him here must have agreed to be replaced. It was a scenario that he’d considered but in his own world his fight to keep his job had created real acrimony. So, that was a thing he clearly had gotten wrong. Although, if there were an infinite number of worlds in which he stayed as technical lead, that same decision would have been a mistake in some of them. What he knew for sure was that there were worlds in which he’d accomplished something meaningful, and that he was getting a do-over.

He pulled his phone out of his pocket and typed Buys Sigmoto into the browser and stood under a massive fir tree halfway up a wooden staircase as he read about the purchase by a company called Peerteq. The unconfirmed price was eye-popping. There was even a quote from him saying Peerteq was the kind of perfect strategic opportunity that only comes around once.

Buoyed by the good news, he decided to check his email. At the top of his inbox, his financial advisor, someone named Edgar Wylie, had sent a status update on a couple of transactions. Vin had a lot of money. The second email was from a name he recognized, John Grassler. Its subject was Got it and it said:

Vin, we found it, and you were onto it. You were close. But there’s really no question anymore. The security breach was the result of a bounds-checking thing, but not that simple. It’s only possible because of the way you put together the core. It’s a spot I was supposed to refactor but I de-prioritized it during diligence. I’m so so sorry. Come in today and I’ll walk you through it.

As he was reading, an email arrived from samwelltarly99q9@hottymail.com, with the subject: You Moth4rfucking Life Sucking Poisond Sack OF Ball Sweat. It started,

You lied lied lied, and then you fucked me over when you didn’t have to.

He couldn’t read any further. He was surprised it got past the spam filter. He deleted it and turned off his phone.

Was he in love with her? That was the question that waited for him as he opened the door to the big house, and he knew that he was asking himself about Nerdean, and not about Kim. He couldn’t have loved Nerdean, though. He couldn’t even be sure that she existed. But wasn’t it Nerdean, above anyone or anything, who had truly offered him a new world?

Sophie came padding into the dining room and made a quiet yowling sound that tapered into a long, low growl. She often seemed angry with him, as if each day began with a ritual of him neglecting her. He walked over to pet her but she ran from him and then waited near the island.

As he forked the contents of a can into a bowl, chopped and mixed the oily pâté, he was aware of a thought trying to shape itself just out of the reach of his awareness. He bent to scratch Sophie’s head and stroke her back as she pushed her face into the bowl and purred.

No matter what else was happening here—the wealth, the security breach that could jeopardize what he had built (a breach he, uniquely, might be able to mitigate), Bill’s happiness—no matter what else was happening—Trina and Kim were not here. He sat at the table until Sophie walked away from the bowl then got his laptop and sent Bill a short email. I couldn’t imagine a better friend.

He walked down to the basement where he half expected to find that the switch in the carpet and the chute to Nerdean’s office were both gone, and that everything he thought he had experienced since moving into the house had been a dream. But the switch was on the floor near the wall, maybe eighteen inches from where he remembered its original position. It might have moved in different versions of the house, but it was always there.

When he got to Nerdean’s office, he woke one of the monitors and at the password prompt he typed I am Nerdean, including the spaces because he wanted to make a statement. He had only wanted to prove to himself that he could type those words, but a moment later the system cleared to show a desktop he hadn’t seen before.

He searched the account for additional files, more information, greater access, but found almost nothing new. Almost. There was one thing. In a directory that had previously held only a text file, he now found a small application that ran a crude user interface with a single control, one horizontal line stretching between the labels NEAR on the left and FAR on the right. A gray box, a crude slider, sat halfway between the two labels. He moved the slider all the way to right, as close to FAR as it would go.