And What Are You Looking For?

He’s in the crèche, but in this shot he is himself. He’s not inside anyone else’s mind. He’s standing in a great, spreading meadow that’s filled with activity. He knows he’s on a shot because he has a clear memory of being clipped into the crèche’s wiring and submerged in broth just before blacking out and then waking here.

A soft breeze plays against his cheeks and he finds himself facing Mona. She’s smoking a cigar, a half-inch of ash hanging from its tip, the cloying smell of sweet tobacco smoke wafting about her.

“Well, sleeping beauty joins the party,” she says, in a growly, throaty version of her deep voice. He turns in a slow circle. There are people in every direction, moving swiftly here and there, most wearing what appears to be heavy, metallic armor. A few are in military fatigues, a very small number wear silver and white gowns, one person in the far distance appears to be wearing a tall hat. As he watches, an androgynous couple who may be identical twins float by trailing long orange-and-black trains of shimmering fabric.

A hovercraft zips past overhead, oddly quiet. In the distance, a convoy of heavy trucks is rushing across the field. There’s motion everywhere.

“Hey, over here,” Mona says. “Look at me.”

Mona’s face is scarred, her nose flatter than he remembers, as if it’s been broken more than once. She is also encased in what looks like heavy armor. She pulls a two-handed, cannon-like weapon off of her back and holds it in front of her.

“What’s going on?” he asks. “Where is this place?”

“This is the future,” Mona says, her lips dexterously moving the cigar to the left side of her mouth. “So, ‘I am Nerdean,’ huh? You figured that out? Well, welcome to Armageddon. You good now?”

He shakes his head and says, “No.”

With the right side of her face, Mona says, “Alrighty then.” Mud splatters from beneath the heavy metal boots she’s wearing as jets fire under them and she starts to lift off from the ground.

“Where are you going?” he asks.

“Back to the fight,” she says, her voice humming with satisfaction. “I’ve spent enough time being your nursemaid.”

The jets in her boots roar and screech and she drifts upward. He lifts his hand to shield his face from heat that crisps the hair on his arm. She accelerates as she rises and soon disappears into the sky, leaving a faint, curving contrail.

He recognizes many of the people around him. Several are other Monas. And a dark-haired woman about forty feet in the distance is walking away from him. Kim. Even in her armor, he knows it’s her and the sight of her provokes a lumpy pain in his throat. He steps forward, but a man in armor with a helmet held under his right hand comes between them.

The man says, “Hey.”

“Do I know you?”

“Hey, motherfucker, it’s me.”

“Is that—Bill?”

“Yeah, man. Always good to see one of you join us.”

“Bill, you’re black.”

“And in my world, you are too.”

“I—” Vin is stymied. The man’s face is almost composed of Bill’s features, but slightly different. The look in his eyes though, and the sound of his voice, are Bill’s. He stands with his chest forward, as Bill’s would, with his weight shifted toward the balls of his feet. His chin is high, hiding his fear the way Bill does.

This Bill says, “I see, you haven’t been here before? That’s too bad. I was looking for a partner for an attack. But, you should probably get oriented first. Sorry, I thought you might be cycling through a second time or something.”

“No.”

“Well, okay, I can give you the basics, anyway. I don’t think anyone can actually explain all of this.” He laughs. “This’ll be sort of an ad hoc thing, but that’s really all most of us get. So, first, I guess the fact that I’m black is important. You can tell I’m not from your world. You may know me, but don’t make too many assumptions. That’s good as a general rule for people here. Second thing is, obviously, this place is different than most of the others. I think that this is a far, far future. They’ve had crèche technology here for a long time, and are good at it, very good. You are actually in this place and if,”—Bill’s face suddenly screws up as if he’s in terrible pain. His head starts to swell, it happens quickly, skin weirdly separating from bone until his skull pops softly—his skull explodes—slapping Vin with a spray of blood and sharp bits of bone. Bill’s headless body rolls onto itself and falls to the meadow. As Vin is gasping and spitting out the taste of blood, another Bill, also black and also in armor, hurries over.

“Shit,” the new Bill says.

Vin can’t speak. He bends to put his hands on his thighs and turns away from the bloody mess that had been a neck. One of his hands is moving on its own, wiping at sticky brains and blood that plaster his soft cotton shirt to his bare chest.

“You okay?” asks the second Bill.

“What was that?” Vin manages. “Is he going to remember that?”

“Remember?”

“When he gets out of the crèche?”

“Oh. No. You haven’t been oriented, huh? No, he won’t remember. If you’re killed here, then you’re dead, okay? You die back in the crèche. So that version of me is dead. Are you alright?”

Vin shakes his head. Vomits. Bill puts a hand on his shoulder as his body shakes. The vomit is oddly gold-colored, shining. Vin is leaning forward, hands braced on his legs.

Bill says, “I can see you can’t help it, but we need to be quick here. We’re always under attack. Even right now. It’s kind of like archery coming over castle walls. The enemy’s trying to soften us up by sending waves of random death events at our causality shield. Every so often, one gets through. And—” He nods toward the mess that was the other Bill’s body.

“Who is the enemy?”

“He didn’t have a chance to cover any of that with you? Before he got hit?”

“No.”

“For now, I guess who the enemy is probably isn’t that important. And, just so you know, we’re doing the same thing to them. First things first though. We need to get you into some armor.”

Vin stares at the heaped body—veins and hints of structure, maybe a chip of spine—but he’s also starting to pay attention to the efforts of his right hand, which is still swiping at the remains on his face and chest. And he’s trying to spit out bits that are dripping from his upper lip, and not allow more into his mouth.

The new Bill touches his shoulder. “You’ve got to put yourself back together. C’mon. Follow me.”

Vin straightens, muscles and joints slowly unclenching. He walks in shock past Monas and other Vins, other Bills, and other people he doesn’t recognize. Of course, this means that Bill used the crèche. That would be Vin’s fault. But then again, if it were possible for Bill to use the crèche, he would have. Somewhere.

There are also several of the thin, gray-haired woman whom he first saw in the crèche, and many Kims. Many people are wearing metallic helmets. Vin can’t see who they are.

The Bill walking beside him says, “Okay, man, here’s what I think is going on, but the truth is, I don’t actually know and I don’t know that anyone does. People say this place was created in a future—a far future from our time. And, one thing they did was build it big enough to accommodate any number of travelers, maybe like, literally infinite people. So, then, maybe what they didn’t understand was that because of its sheer size, it created this huge radius of probability, a probability sinkhole that attracts people who try to shoot themselves into the far future. Maybe that was what they wanted, though. What’s really, completely cracked, is it took on its own reality. Because the technology was manipulating—ah, I don’t know. Shit. But now it’s a real kind of place, a manufactured fork in dimensions and out of control. They say it doesn’t split the way normal dimensions do but just adds to itself, so it’s, like, eating other dimensions. Try to get your head around that. We call it Armageddon. Maybe you gathered that.”

“But, why are you fighting?”

“The fight? Well, that’s simple. Survival. I mean, when I first got here I realized this is what I’ve always been doing. It’s just more honest here. It’s kind of what life’s about when you factor out the living.”

“That’s terrifying.” Vin isn’t sure he’s hearing Bill correctly and is yo-yoing between states of panic and numbness, his heartbeat surging painfully then slumping into fatigue.

Bill says, “Funny though, some people feel better here than in worlds like ours.”

“Those people are terrible.”

Bill looks like he’s about to say something, but doesn’t. The sounds around them seem almost unsynchronized from the movement they see, like a video with a fractionally delayed audio track. But Vin can’t be sure. It’s slippery. Anything he pays close attention to becomes synchronized. It might just be his general feeling of disorientation. He says, “Do you talk with them, the enemy? Why do they fight?”

“Same reasons, I assume. But I haven’t been on their side. I don’t think.”

“You don’t think?”

“Well, yeah. You know how it is. It’s confusing. I think maybe their side looks like ours. When I come here, everything is always the same. And, you know, infinite people, or so many you can’t tell the difference, flying up into the sky to fight infinite people. Everyone in armor. I mean, you might not know who’s who.”

“You can’t tell the difference between them and you. That’s what you’re saying?”

“I said maybe.”

“So, people appear in this world. There’s a fight. No one knows why.” His voice trails off and they walk in silence. A small cluster of helmeted and armored figures is having a conversation. One of them flashes a thumbs-up at Vin. As a group, their boot jets fire and they begin to ascend. “And death here is real,” Vin continues, watching them rise, “and we can arrive on either side. Maybe, side A. Maybe, side B. And human beings made this.”

Bill makes a kind of growling noise. “It’s almost like you’re purposefully not getting it.”

“Okay. What if you and I were to just start fighting, right here? If I were to attack you right now, what would happen?”

Bill stops and puts an armored hand on Vin’s sticky, bloody chest. “I suppose that would make you one of them. Look, man, don’t freak out here, okay? It doesn’t help. Not at all. This place is actually as fucking deadly as you think it might be. I’ve been here a lot. I know. Your job is to get out alive.”

“Alive?”

“Yeah.”

“But you just said this is what life is about, when you factor out the living.”

“Yeah. I believe that.”

“You choose to come back here.”

The distance between them doesn’t actually change but feels as if it may be twisting. Strong, unknown scents are turning on and off in the air. Bill says. “I’m trying to find something better, like everyone. I don’t avoid this place, though. Look, you have to kill to eat. You kill things to build. You kill to protect your family. This place is just uncomplicated about it.”

“Bill that’s—some fucked up death cult shit.”

“It’s just survival, man. We’re all part of something that pits us against each other. When it’s hidden, I just feel despair. People may have made this thing, but there’s a reason it grows on its own. It’s a clarification. And that word, survival, maybe it’s like infinity, or probability, words that are just the sound of your brain giving up, in English.”

“No, those are ideas. We can work with those things, we can understand them. They’re math.”

“Jesus. See, you’re such a fighter, man. If it doesn’t make sense to you, you fight it.”

“This is bullshit. We don’t have to do this.”

“I thought that too, once. But you know that’s just another kind of fighting, right? Resistance. And it can be infectious too. So, if you resist, you end up on the other side, and the people here kill you. It’s true no one knows how the sides get made. Maybe Vins are always on our side. Maybe you guys get split up.” Vin has a sudden moment of blankness as he realizes that he’s hearing a threat in Bill’s voice. Bill says, “I should warn you, man, a lot of you Vins die here. A lot.”

Vin’s eyelids are getting stickier as blood dries on them. He rubs them. Bill waits, says, “Armor?” Vin, feeling sick, nods, and they keep walking. The field is covered with a tough and vivid green grass, moist, a few inches long. It folds under their feet but doesn’t seem damaged by their tread and they don’t leave a trail.

Despite the many vehicles, some wheeled, some flying, there are few sounds of engines about them—primarily the loud, Doppler-stretched whines of rapid motion, and a constant uneven surround of many voices. Beneath the odd fragrances that seem to come and go, the field mostly smells of freshly cut grass. Sunlight sparkles like poured gold between standing and walking bodies.

Vin says, “Nobody seems bothered by what’s happening.”

Bill stops walking again. He’s making a tsk tsk tsk sound and shaking his head as he looks away from Vin. “You still don’t get it, man. You have to stay buttoned up or you will die. I just saw my own head blow up. There’s plenty of people suffering, but we don’t show it. Weakness gets you and people you love killed. The Vin from my world understood that. And, by the way, that’s not the first time I’ve seen myself killed. How do you think I should react to something like that? What would satisfy you? I’m doing what I can, and right now, I’m helping you.”

As they’re facing each other, Vin sees the Bill he knows, the Bill he has a history with. And he also thinks he notices a subtle thing about the air. Breathing it is sending little micro-jolts of panic through him. It’s not just the smells that stop and start. It’s almost as if all of the air, even the air in his lungs, were blinking out of existence for microseconds and then returning before its absence changes anything, but his body can feel it. Why build that into a manufactured dimension? Could it be a bug?

“This place, the fighting is pointless. There are no answers here.”

“No, man. That’s not right. There are two sides. That’s an answer. The fight.”

“It doesn’t explain anything.”

“I love you man, but this fight is happening. Pick a justification. The fight is what matters. You Vins have your heads in the clouds. You have to focus on your game here, or you won’t survive.”

At a freight truck with its rear doors rolled open, Bill and a woman Vin doesn’t know find him armor and a weapon—a long, shiny gray tube with metallic protuberances. The parts that stick out have triggers on them. With the safety on, Bill shows him how manipulating the triggers can cause the tube to fire a variety of lethal ordnance. The tube clicks with magnetic certainty onto a flat area on the rear of Vin’s armor, leaving his hands free as needed. The armor fits as comfortably as loose cotton clothes and doesn’t feel as though it has any weight.

Bill talks Vin through what’s expected of him. Assuming he survives this shot, if the crèche ever sends him to Armageddon again he’ll be expected to suit up on his own, find others willing to accompany him to the front, then go there and fight. Most of the people around him are veterans of the environment and can answer questions. Bill suggests that he connect with a Mona, if he can get one to talk with him, as they’re generally considered exemplary warriors of Armageddon. While Bill is helping, Vin is only half paying attention. He is distracted by the repeating mental image of the first Bill grimacing in agony, his mouth stretching open, cheeks and forehead knotting down over his eyes as his head begins to expand.

Bill points out that Vin’s armor includes jets and suggests Vin practice flying before going into battle. Then he fires his own boot jets, and before he streaks away, tells Vin that the armor will protect him from enemy fire and random death events, which means that for safety, Vin should always wear his helmet.

From the inside, the helmet is invisible and the world looks exactly as it did without it. It seems to fit poorly though, and slides a bit across the back of his neck and knocks against his nose when he moves his head quickly.

Vin curls an index finger into his palm to fire up his boot jets, as Bill showed him. The pressure balances across the soles of his feet as he lifts off the ground. Bill told him there were stabilizers in the armor.

Vin isn’t sure whether he actually has a body in this place. His “real” body must be in a crèche in some other world, and so he’s not sure whether he’s wearing any actual armor at all, in any sense he’d understand. But, whatever is happening, the flight feels true—joyful, liberating—and he doesn’t have any trouble directing it.

No one seems to be paying attention to him. He spends the rest of the shot flying from place to place across the field, trying to convince himself that no one cares that instead of contributing to the cosmic battle of us versus them, he’s just playing with his equipment. And he thinks Bill has it wrong. No matter how overwhelming the reality of the place, there is more to living than a brutal and arbitrary fight for survival. There is flying, for example.

He leaned forward, coming partially out of the casket. Dumbfounded again, scrambled and worn by the shot. His limbs felt drained. His mind was active but deadened, a dizzy zombie. The crèche was a trauma marinade. All those people fighting. A warm bath would have been a better vehicle for changing the world.

This variation on Nerdean’s office was cool and dark, an unusual gloom shrouding its corners. The light was weak and fragile, portions of the glow-strips on the ceiling were off and he couldn’t hear the AC.

He stepped out of the third casket, the one furthest from the chute, and put on the white terry cloth robe that was hung over an eggshell chair. He turned toward the rack of servers. Only two appeared to be on; there were no lights on the others. On the back wall, the lights of some batteries were green but some were yellow, a few were red, and some bezels had no lights.

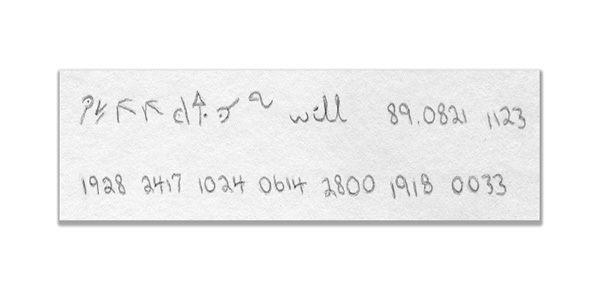

He picked up the notebook and flipped through it quickly, looking for unexpected entries. It all looked familiar. Only one computer screen would turn on. He logged in with I am Nerdean, and looked for clues that might explain why this office was different, but could find nothing. He considered going back into the crèche and leaving this world.

The third casket, the one he had just left, began its cycle of rejuvenation, its exterior lights blinking in the gloom. No lights illuminated the other two. But the transparent pane on the middle casket, number two, was oddly shadowed.

He opened an empty document on the only computer screen that worked, turning the screen white, then found a button to increase its brightness. He tried to angle the screen so its light would fall on the middle casket.

Something large and dark filled the interior there. Straining for detail, he saw that the thing inside was partly transparent, had a blue hue, and contained a deeper shadow that might have the form of a body. He traced a roll of darkness—an arm—to its end—a hand, fingers curling in. The blue broth had hardened around a person, sealing them in.

A breaking clangor, the sound of metal raking across metal, rose from the casket he’d just exited, followed by an extended thrashing noise. The lights under the lid turned red and started blinking. As he watched, all the lights faded and went out and the noises ended. Silence washed the room. Then the crèche seemed to restart the cycle of rejuvenation. Its lights came on at the beginning of their sequence, but the device also made muted squealing sounds.

The lid of the chute made a sucking sound as it lifted and a briny smell with a familiar tang of iron dropped into the narrow space. The room above was dark. He placed a hand on the rug outside the chute but pulled it back immediately. His fingertips were wet, bloody.

He pushed himself back so he was leaning against the wall and took a slow breath. Should he go up or down? He couldn’t hear any sounds above. He pulled himself up and peered into the basement room, gagging softly. He turned to his left and almost fell back down the ladder. There was a body lying on the floor, staring toward the chute. Kim, eyes open and lightless, the lower half of her face a reddish-black blur.

He retreated. He hung on the rungs in the dark shaft until the smell of death filled it and he could not be still any longer. He climbed out, keeping as far from the corpse as possible, but spotted a child’s body tumbled on the carpet in the back of the room. He closed his mind. He knew who the other body was, who it must be. He closed his mind and floated. And found himself upstairs.

The dining room was dark, heavy curtains drawn across the picture window. Mona sat at the long dining table in a white robe like the one he was wearing, her elbows pressed on the table, her hands covering her face. She didn’t look up as he approached, as he paused to steady himself on a chair.

“Mona,” he said. She turned to look at him and shook her head in incomprehension.

“Do I know you?” she asked. She shook her head again, startled.

He walked into the kitchen and pulled a long knife from the wooden block. Her gaze flicked to the knife then back to his face.

He said, “Downstairs, did you do that?”

“No. No.” She drew back in shock. “I would never do that.”

He walked to where she was sitting and brought the knife close to her cheek, the blade just below her eyes. “But you have done that at least once before, haven’t you? To your own family.”

She looked up at him. She wasn’t scared. She didn’t care. Why should he believe anything she said? He brought the long blade to her throat, just below her chin so that when she breathed her skin pushed against it. It was a sharp knife. The cut would be firm and fast.

“They were shot,” she said, her voice level. “I don’t have a gun. I don’t even know who they are.”

He tried to remember how Kim and Trina were killed. Kim’s jaw destroyed, perhaps the back of her head gone. He took a step away from Mona and suddenly the lightness left his limbs. He sucked in air until his chest felt like it might explode. He lowered himself onto the edge of a chair, slipped into the center.

“I could never do that,” Mona said, hatred straining her voice. “But I think you’re someone who could, aren’t you?”

The words stilled everything else. He didn’t know. His body vibrated, struck by passing seconds.

“Maybe you did do it.” Mona’s voice was throaty. She spoke slowly but she wasn’t accusing, only evaluating him, reading him as if what he was were plainly written in his face, on his body. “Here or in another world, you could lose your temper. Just like that. Couldn’t you?” But then her head sagged again as if the room were filling with all of the disappointment of life. “And after that,” she said, “you’d just go on, wouldn’t you? Because what choice would you have?”

A wire broke inside him. A machine in his mind that enraged and aimed him, automated decisions, would defend itself by destroying her and him. He placed the knife on the table between them.

Neither of them had moved and Vin had almost regained control of himself when they heard the front door open. Mona was tilted forward, staring blankly. Vin felt welded to the chair but his head could turn. He said, “Joaquin?” and Mona looked up.

Joaquin was staring, unblinking, at Mona. At his side was an enormous revolver, the kind that doesn’t fill a hand as much as consume it.

“I’m sorry,” Joaquin said to Mona. “Please. Please, come back.”

Other than the look of loathing frozen on her features, Mona hadn’t moved, but everything about her was different. She was alert.

“You know each other?” Vin said.

Joaquin’s mouth tightened in acknowledgement of Vin’s presence. “I asked you to stay in this house, Vin, in the hope that you would find her. We are married. She killed my children.” As Vin struggled to reshape his past around this new information, Joaquin continued. “She was a general contractor. She built this house. She introduced me to Nerdean. Through email.”

“It was an accident.” Mona’s voice was low, controlled. “They weren’t supposed to be there.”

Vin said, “What about my daughter? And Kim?”

Joaquin’s mouth fell open slightly and he took a longer breath. “I am sorry, Vin, about Kim and . . . I am truly sorry about them. I needed Kim to show me the machine. You lied to me, Vin.”

“I didn’t.”

“You did,” Joaquin shouted the second word, his face flushing, eyes clenching, spit flying from his mouth. He regained his balance at the edge of the stairs and said with effort, “I wanted you to find my wife so I might help her. Because she is dangerous and I did not want this”—he stopped talking, stared at Vin and said—“or anything like this to happen. But you would not stop lying to me. Even when your pretext was transparent, you lied. You did this.”

The gun was aimed at Vin again and an asymmetry caught his eye. A single coppery glint showed on one side of the big revolver’s barrel.

He caught a blur in his peripheral vision. Mona had risen and was flying toward Joaquin.

It was not a sound—more a cataclysmic motion of the house. The gunshot blew the air out of the room and threw the three of them together into a new world, a universe birthed in that shaved second of violence. Blood sprayed from Mona’s back and the huge picture window behind her cackled and shivered into an obscuring web of stilled moments.

Mona straightened. It was as if she had been cored, the back of her robe red from the spasm of blood, but she didn’t even look at her wound. She took a staggering step toward Joaquin. A tinny crack, crack—the sound of the gun’s hammer falling on empty chambers.

Mona had the knife in her right hand. She swayed away from Joaquin, almost tipped and fell backward, but then miraculously swayed the other way. She took three more falling steps and shoved the knife deep into his gut.

His face went taut. Mona pressed forward and jerked up on the knife, pulling the long blade through him. As they pressed into each other, their bodies held upright by their opposing weight, Joaquin’s face paled and the stalk of his neck wilted.

Mona made a sound, a soft chuckle of blood bubbling from her mouth. Vin ran to them as they sank to the floor, leaning into each other. He kneeled in the spreading pool of their blood, reached a hand to Mona’s shoulder. She blinked as if returning to life and looked at him, her eyes rolling, head not moving.

“Vin,” she said, struggling to form the word, her shallow breath seething between bloody teeth. She and Joaquin were fused in a gory mess. Vin couldn’t see what had happened to her.

Vin said, “Let go. Let go of the knife.”

She didn’t let go, and as he strained to pull Joaquin away from her, tendrils of viscera came too, spinning apart at the knife’s edge as it slid out of his gut. Joaquin’s body collapsed to the side and Vin pushed it away. Then he pressed on Mona’s wrist and gently took the knife from her.

She folded to one side and he helped her onto her back. She was wide-eyed, staring upward. “I’m going to die.”

“Yes. I think so.”

“I used accelerants. My babies weren’t supposed to be there.”

“What can I do?”

“It’s okay. It was a fight I needed.” Her eyes closed but she was still breathing.

Vin worked quickly. Mona was not a large woman and adrenaline lent him strength. He tore strips from the robe, which separated cleanly, and used the robe’s sash to tie the strips tightly against her wounds. As he carried her into the chute, remnants of the robe caught on its lid—he simply tore them apart and continued with his fireman’s carry.

She hadn’t spoken since he’d picked her up. When he laid her in the first casket she was pale but still alive. He could see her shallow breathing and as he removed the sash and pieces of robe he felt her pulse whispering through her cool flesh. Nerdean’s office was busy with muted scurrying sounds, scrapes and squeals from the damaged third casket that was still battling through its cycle of rejuvenation.

“You didn’t call the EMTs . . .” Mona came to as he was finishing his frantic work on a keyboard. The third casket entered a quiet phase in its cycle and her voice was a hoarse whisper. He stepped quickly to the side of her casket.

“Thank you,” she said, twisting her head slightly to look at him. Her eyes were clear but her voice was fading.

“I don’t know if this will work.”

“That’s okay,” Mona said. She was going to embark on a shot, one way or another. He found the sedatives and bottled water and she managed to swallow a pill.

“I found another password,” he said.

“Yeah?”

“Yeah, so I can set how far—”

But her eyes drifted slowly shut and he knew she had been pulled under. She was still breathing. He ran to the computer and pressed a final key to fire the shot. The lid of the first casket lowered with smooth precision and sealed her in.

He didn’t know if she’d make it to Armageddon, didn’t know if she’d even survive until the shot started, but it seemed possible. The crèche was designed to incubate, to support, nurture and heal the body, no matter what else it might do.

He sat for between ten and thirty minutes with the third casket grumbling through the end of its cycle of rejuvenation. Shortly after it finally fell silent, he recalled himself. He stood and walked to the first casket and placed his hand on its transparent pane. The mist cleared and he saw Mona floating peaceably in the slightly rust-tinged broth.

On the desktop, Kim’s phone buzzed. He had retrieved it and placed the baby monitor outside the front door. It was notifying him of noise. The casket’s transparent pane sighed and misted as he lifted his hand and hurried to the desk. He heard the shriek of police sirens and closed down the monitoring app, silencing it. A police forensics team would definitely find the chute, and Nerdean’s office.

In the urgent quiet, he peeled off his bloody robe, sat at a keyboard and opened the controls for the third casket. He keyed in a command and the third casket’s lid lifted with a squawk. At least it could still open. That was a good sign.

More of the batteries along the far wall had gone dark. He wasn’t sure whether the casket would work for even a short shot, and he didn’t know of any way to use it without landing another version of himself in the mess that he was running from. Maybe even infinite versions. But he hadn’t made this mess. Did he have a responsibility to stay in it? At least Mona’s body might die, so no other version of her would end up in this shithole. Her death would free her from this particular world.

He checked the duration, and then pulled the slider for the third casket all the way to the left, as close to the label NEAR as it would go. He had the presence of mind to worry for a moment about what near might actually mean—might the crèche project him into a version of his own mind? But he left the slider alone. Mona may have chosen to go down fighting, but Vin did not want to return to Armageddon.

It’s late and chilly and he’s sitting on a concrete staircase looking out at the glittering Seattle skyline from the south shoulder of Queen Anne Hill. His name is William Marigold and he’s thinking about smoking a cigarette. He used to smoke and he misses it.

The sarcococca ruscifolia is near the end of its bloom but still managing to spread its delicious, spicy vanilla scent. The smell might not be so bright if he hadn’t quit smoking when he did, many years ago.

Fragrant sweet box is the plant’s common name. It was one of his favorites when he cared about things. The flowers are small and humble but when they’re in bloom they can pack a breeze with a scent so fine it can stop a jogger cold. He’s seen puzzled, spandex-clad runners halt midstride and then follow their noses around the foliage, sniffing nearby plants, looking for the source of their pleasure. The flowers are so modest that sometimes people don’t think to smell them. Once you know the secret though, you look for them. If you still possess that magic feeling of giving a damn.

William looks up at the shadow-clotted sky. He’s been thinking a lot about eternity and how close it always is. One single motion can take a person from useless to infinite.

Vin is in William’s head and the dull, burdensome sense of being in a place—the almost unendurable weight of the sky above and the weight of being in a body and pressing down on cement and dirt—alerts him to his existence. The crèche did this to him.

“The crèche?” William thinks. “What’s that?”

“Oh no,” Vin thinks. “He can hear me, like the cannibal.”

“No, I’m a vegetarian.”

“Oh. Like Bill.”

“No, I prefer William.”

William stands—a prickling pain in his left knee. He rubs his right elbow to check that the bump beneath his flesh hasn’t gotten any larger. His doctor says it’s benign, only a fat deposit embedded in the flesh near his joint. It may be, but it’s also an intrusion in his body, a thing that shouldn’t be there.

It’s a warm winter night. Unseasonable is the old term. Presaging doom is the new, more accurate way to think about it. Thirty to thirty-five billion metric tons of CO2 emissions per year. Probably more now. Warming the surface of the earth as if it were a green pea in a convection oven. But William stopped tracking all that long ago. He stopped seeing the point. Any one person is able to recognize and avoid danger, but the human species as a whole is incapable of responding to it effectively. The human species will defeat life at last and the earth will sizzle under the solar lamp until it becomes a dry shell.

Once he stopped caring, the world opened a great distance between itself and him. Even the air, mild against his skin, reaches him now only by crossing a gulf. As he walks up the slope toward the basement apartment that he rents near a park, he sees himself walking as if he were hovering above and behind his own body.

He’s imagining the perspective. Of course, he knows that. But if he could actually see himself from that perspective, he would see that the crown of his head is shiny with grease and thick with embedded flakes of dandruff. It’s like that no matter how often he cleans it or how well he grooms himself. It’s a sad fact that the memory of only a few sneering rebuffs from people you might have loved can leave permanent, grimy streaks on your self-image.

Though the globe is warming, a warmer winter is pleasant for most people. In that way, temperature change is like a helium balloon, very nice, inspiring even, when you first notice it—vivid and colorful, defying gravity—until it pops. Then it becomes an elastic environmental poison.

At the top of the hill he turns back to look at the skyline while he catches his breath. Vin notices that some buildings are missing.

“Oh?” thinks William. “Why is that?”

“Well, I guess they must not have been built yet. But you shouldn’t listen to me. I think you have enough to worry about.”

“Okay,” William responds meekly.

“Do I frighten you?” asks Vin.

“No. I’m much too frightened by real things to be frightened by an imaginary voice in my head.”

“I’m not imaginary.”

“That’s what they all would say, I’m sure.”

“You have other voices?”

“I might have. But what I mean is, all psychotic voices would tell you that they’re real. That’s a part of the illness, isn’t it?”

“Are you psychotic?”

“I suppose I might be. I’m talking with a voice in my head. You might be a psychotic break. I suppose. But I don’t really care. One more reason to kill myself.”

Vin is silent after that remark, but William doesn’t care whether Vin responds. William sniffs and places the palm of his hand against the end of his nose, which is cold and starting to drip. He wipes his palm against it, then wipes his hand on the side of his parka and keeps walking.

“Don’t kill yourself.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t really know you, but—”

“Interesting.”

“—I can tell you that this has been a particularly shitty day—”

“Yes, I agree. Another one.”

William doesn’t so much dismiss Vin as just move on, as if Vin were a thing that should dissolve when neglected. William begins to think about the question of weight, and how much exactly is pressing on him. He steps through a lengthy back-of-the-envelope type of estimate, figuring the weight of the atmosphere at sea level in the mid-Northern latitudes (excluding the vast exosphere, whose contribution would be negligible), the height of Queen Anne Hill and the resulting height of his shoulders above sea level. He concludes that roughly 2093.5 pounds per square foot is bearing down on his head and shoulders, which confirms his expectation that simply standing up in this world is a burden.

Observing William working through his mental estimate, Vin is impressed, but can’t help remarking, “That’s a whole lot of work to shave off a total of only twenty or so pounds per square foot from the standard atmospheric weight at sea level.”

“I do it because I’d really prefer not to exaggerate,” thinks William. “Once more, the truth is frightening enough.”

Vin doesn’t bring up his real concern until they reach William’s apartment, a dank claustrophobic studio in the basement beneath a large Craftsman house that squats across the street from the West Queen Anne Playfield. William flips on the overhead light as he enters but the bulb barely wakes the comatose room. The apartment’s small windows are covered with blackout curtains, the furnishings old and abused—a faded, light-blue, broken-backed sofa; a recliner covered in a frayed floral pattern, its cushions pancaked by years of reckless flopping down. Slips of paper spread like a scatter of severed wings over a small breakfast table, glossy magazines in a slumping stack beside the couch.

“Are you still there, voice?” William asks himself.

“Yes,” says Vin.

“What’s your name?”

“If I’m in your head, shouldn’t I have the same name you have?”

“Well, do you?”

“Vin. My name is Vin.”

“I see. So my suspicion was correct. You are a robust enough hallucination to have your own name,” thinks William. “That is depressing.”

“No. No,” Vin thinks. “It’s not fair to trick me into saying things that will make you feel worse. And I’m not a hallucination, I’m real.”

“There is no conceivable way that you could be anything other than the kind of short circuit in my mental function that I’ve been anticipating now for years.”

“Yes, there is,” Vin says, surprising himself with a decision. “And I’m going tell you exactly how. But first, I want to get something straight with you. That whole thing about estimating the weight on your shoulders, atmospheric pressure doesn’t work that way and you know it. It presses in all directions, it doesn’t just drop a ton of weight on your shoulders. You just calculated a single vector to validate how you feel, but it operates in a system.”

William opens a stained green refrigerator and extracts a nearly room temperature Budweiser. When he pushes on the refrigerator door it drifts closed, barely sealing.

He thinks, “Okay, Vin, I did exaggerate and you caught me. But every answer is an estimate, and my feeling is genuine. So now that you’ve proven to be a more perceptive voice in my head than I expected, can you tell me why you’re not a hallucination? Maybe your story will help me sleep.”

Vin spills images and events as if he’s confessing and everything he says will be forgiven. William is attentive, and Vin feels him waking mentally, slowly rousing himself from what had been a profound and lengthy funk to pay closer and closer attention to Vin’s story. William is a good listener, and from inside William’s head, it’s easy to convey emotion. William’s rare questions are thoughtful and sensitive and they test Vin’s awareness of Kim’s feelings, and Trina’s. They test his awareness of his own resilience.

“It seems to me, Vin,” William says at one point, “that you and Kim treated each other well while you were together.”

“Thank you,” Vin says, dizzy from their many beers.

William is horrified by Vin’s trip to Armageddon, and when Vin reaches the bloody climax he has just fled, William gasps at each grisly development until, as Vin relates how he loaded Mona into the first casket, William is sighing noisily. Vin has been afraid that William would challenge his decision to use the crèche, rather than call an ambulance. Maybe Mona could have survived. But survive for what? Her phantom responds.

“You made the right choice,” agrees William.

Throughout the story, William is an accommodating surrogate, allowing Vin to move his hands and mouth so they can take turns drinking beer. The two of them have kept each other going and drained many of the bottles in William’s sickly but well-stocked refrigerator.

“Ah, god. It’s so sad,” William thinks as Vin explains how he landed in William’s head.

“I know,” Vin agrees, and then he’s gasping, weeping without restraint in whatever way a thought process can.

“We’re so cruel to each other,” William thinks.

And Vin thinks, “William, please don’t do it. Please.”

Vin can easily hear thoughts that William intentionally directs at him but the deeper layers of William’s mind are clouded under a mordant, almost fungal coating, a powdery glaucous bloom. Contact with them drains Vin, makes him feel grimy.

William thinks, “I know a girl who calls herself Nerdean. She’s only fifteen though. We play Go at the Queen Anne Library.”

“What?”

“Hey, stop poking around in my thoughts.”

“But if you know Nerdean, and she’s young, and I just told you about the crèche, then you might tell her. What if I’m responsible for her creating the crèche?”

William is appalled at how thick Vin is being. “Isn’t that just the point,” he thinks. “Isn’t that just what we’ve been talking about? Shared responsibility? And, anyway, don’t get too excited. There are other ways of looking at it. Infinite worlds is just hand-waving. Infinity isn’t really a number, after all. It’s the distance between math and truth, and I mean that literally. And maybe the crèche, maybe all of technology really, is an expression of an as yet unknown multidimensional geometry of causation, systemic effects we can’t fully perceive. I mean, none of us really invent any of this any more than we discover things. When conditions are right, maybe things, ideas, just grow. Like mushrooms.”

William has been sitting for too long. He blinks with blowzy insensibility and then hawks up phlegm from the back of his throat. As he cautiously levers himself upright, his mood clears.

He staggers into his dingy bathroom to pee. “You know, for a bubble in my temporal lobe, you’re actually okay. Interesting even. I thought you were going to warn me about Area 51, JFK and the CIA. Tinfoil hats. It’s nice to have a conversation with my ideas though, rather than just have them pop up. Collegial.”

William flushes the toilet. He runs his tongue across the outside of his upper and lower teeth as he steps up to a stained bathroom mirror.

“You,” Vin thinks.

“What?”

“You. I know you.”

“You are me.” William spits into the sink. “No matter what you think.”

“Do you recognize this?” Vin asks, and he thinks of a black military jacket with yellow piping and gold buttons. He feels a flicker of pleasure vibrate through William.

“Sure. And you know about the rest too, right?” William plods to a long closet and opens a sliding door on a collection of uniforms. He finds a black jacket with yellow piping that’s hanging over blue slacks. “You mean this one. I collect them. My fingers are too long, my knuckles are ugly and knobby, and I have thin shoulders, a wide rump and a roll of fat around my waist. Uniforms hide all that.”

“I need air,” Vin thinks. “Can we walk?”

“I was going to sleep, but okay, I guess.” William grabs the uniform’s jacket. As he steps outside, Vin convinces him to draw in a deep breath. The dark, fresh breeze feeds him but also makes him dizzy. He sways for a few moments then starts walking west, toward the water.

Vin thinks, “This is you,” showing William his memory of the man who interrupted the barbecue.

“Yes. I suppose it is. So what?”

Vin doesn’t know how to have the conversation he’s desperate for. In some worlds, William merely interrupted the barbecue, but in others he wounded Hanna and killed Trina.

William thinks, “You know, I’m hearing you think about all that. You’re saying all of those things inside my head.”

“Okay.”

They walk. In his thoughts, Vin can’t help connecting Trina’s death to Kim’s journey in the crèche and to the destruction of his own marriage.

William thinks, “Okay, I get the picture.”

“I’m sorry. I can’t help it. My thoughts just—”

“No, I understand. You’re saying I’m going to murder a little girl who I don’t know but already love.”

“Given your state of mind, I wasn’t going to tell you.”

“Well, that’s not one-hundred percent true. You were thinking about hiding it from me so I wouldn’t feel worse about myself. Which I appreciate. But you probably would have told me, if there was a chance that it would stop me from hurting her.”

Vin realizes that William understands him too well for even subtle deceptions.

“Yes,” William thinks at him, “that’s right. I do.”

When William/Vin reaches Marshall Park, he sits on the bench and watches darkness begin to loosen its grip on the breezy reaches above the water. William has been planning to kill himself because he views humanity as a plague, an animal with the same narcissistic perspective as every other animal, but one that has uncovered the protean pliability of the material world and is rapaciously and incontinently bumbling through oceans and forests, smugly convinced of its own transcendence from the systems responsible for the creation and nurturance of all life, an animal that “discovers” components and attributes of the natural world as if they were separable from the circumstances they inhabit.

“I know it’s depressing,” William thinks. But the thing he feels is more urgent than depression. It’s more like the despair Vin felt when Bill dropped a bag of meth on the folding card table. William feels it toward the species. He earned graduate degrees from MIT, won awards for his research. “But the species that honored me, or at least its inevitable idea of progress, is a toxin.” William says this out loud. “And that’s how I ended up here, feeling this way.”

“But can’t you find a way through your depression? Can’t you fight it?”

“Like Mona did?” William thinks. “Like Armageddon? Run from the black dog of depression the way Winston Churchill did, or Teddy Roosevelt? Did you know that Roosevelt felt the same kind of overwhelming anxiety and fear of the future as Churchill? Should I be like them and keep myself so busy that I don’t ever have time to think? Blunder through the world breaking and killing things because I’m trying to outrun my own depression? That would make me a part of the illness.”

“I don’t know. Is that your only choice?” Vin suddenly feels a surge of frustration. William is a sad sack, lost and damaged, a man Vin shouldn’t give a damn about. But he’s unique, specific and alive, and being here in his head, even with his depression—he’s beautiful. Vin wants him to live.

“By the way,” William is speaking out loud again, “Sophie was right about you neglecting her. It seems to me that animals we don’t care enough about to kill, we sometimes adopt.”

And William and his depression are now part of Vin’s life. There’s nothing Vin can do about it. He might even be happy about it, the strangeness of it. No matter whose mind he’s been in, it’s always been his life. The shots are him, not side lives where he can dodge reality.

A brisk chill from the water sweeps over William, silencing both his thoughts and Vin’s. High above, the black fabric between clouds is rent by the closest, most energetic and violent stars. They fade as dawn restores the limits of the visible world.

He had felt things that William felt but he wasn’t sure he really understood William. Maybe William would kill himself. Maybe he wouldn’t. These were Vin’s first thoughts when he woke in a mild, air-conditioned version of Nerdean’s office. Waking there meant that he had survived the shot, which meant that in the world where he left the corpses of Kim, Trina, Mona and the person sometimes known as Joaquin, the police hadn’t ended his shot prematurely, and the crèche’s battery power had lasted.

With his first step outside the casket, he felt a familiar stiffness in his leg. As he walked to the terry cloth robe heaped on one of the chairs—a midnight-blue robe—he became reacquainted with his limp.

His thoughts were darting, restive. He was trying not to reflect on his experience, didn’t trust himself to draw conclusions. But his mind wanted answers, its default intoxicant. He would have to make an effort to deny himself at least for a while. If he didn’t do that, he might pass more time searching, traveling from one world to the next, and his life would all be lived in Nerdean’s office.

There was no one in the other two caskets. Upstairs, the card table wasn’t in the dining room, but neither was the beautiful big table that he and Kim and Trina had lived with. Instead, there was a modest maple table with rounded ends. The chairs that surrounded it were functional, squarish, with cushioned seats. There was a sectional in the same place that Kim had once placed one, but not as nice. There were a few other uninspired furnishings. On the largest wall in the dining room hung a big canvas he didn’t recognize, a painting, the outlines of a car and driver in spreading black strokes, defined and slashed through by playful geometric scrolls and a collision of faded prime colors.

There was no cat food under the sink. He realized with a pang that Sophie wasn’t in the house. The odd cluster of electronics was not in the master bedroom, but he did find a phone charging on a black, wrought iron bed stand beside a queen-size bed. He unlocked the phone with his PIN and looked through the contacts. Bill was there. Kim wasn’t. John Grassler was in his list, as well as Corey Nahabedian and even Brant Spence. He was surprised to see Hanna Dawkins—Kim’s co-worker who had come over for their barbecue—in his list of contacts. When he checked his recent calls, there were several to and from her.

He sat on the bed and stared at the shiny phone screen. Outside his window, unfiltered morning sunlight was sharpening its bright knives against the slate-gray waters of Puget Sound. He thought he should probably read his email and try to catch up on how events developed in this world. Instead, he took a deep breath and called Bill.

They arranged to meet for brunch at the restaurant in the Space Needle. Bill’s idea. On their phone call, he’d told Vin that after finally receiving the largish check for their small investment in Sigmoto, he and Charlotte had been discussing what they should do next. She wanted to buy a few acres on one of the islands and start a small organic farm, raise their own food to sell at farmers’ markets. Bill wasn’t so sure.

Bill’s voice was relaxed, and he laughed with an oblivious, unforced ease. Vin decided to save the in-depth questioning for their face-to-face. After hanging up, Vin spent several moments appreciating the fact that Bill was apparently sober in this world. He walked the distance to Caffé Vita, warming up his trick leg.

Trina had liked this walk. They’d often passed dogs leading drowsy owners who carried blue plastic baggies of poop. She called the route, “Going down the hill the long way,” in her child’s voice—the sound that was the unique cryptographic hash that had once authenticated his life. But there was no contact number in his phone for childcare.

The crèche was a technology that could change the world, disrupt culture, but technology followed its own logic, indifferent to the human arithmetic of suffering. Believing in it, relying on it was like worshiping a volcano. He had knowledge and skill. How should he use them? What good could he do?

He was walking by a line of ants that were shuttling pieces of something yellow past a watchful crow.

As he waited for a barista whom he didn’t know to make his drink, he thought of a question for Bill. He took the latte outside, sat in one of the metal café chairs and called. A wall of dark clouds began to draw itself up against the blue distance.

“Hey, when was the last time you talked with Hanna?” he asked.

“Your Hanna?”

That would explain the calls on Vin’s phone.

A shock of memory tore open the mild day, splitting it in two while somehow leaving it whole. Kim and Trina’s bodies in the dark basement. Vin saw himself pressing the silver blade against the soft flesh of Mona’s throat, saw the deadness in her eyes as they stepped to the precipice of her murder. But he hadn’t hurt her. As a part of her own story, she had saved his life. At the world’s terrifying edges, the rumors of endless shadow worlds trembled. Vin squinted into radiant air, felt sleeping moisture on the slow-moving wind.

“Vin?” Bill asked again, his voice bringing Vin back to himself.

“Yeah,” he said.

“Well, yeah, Hanna called me after you guys broke up. Said that you were going through a hard time, and that, knowing you, you might not reach out.”

Vin was fighting to regain a place in his body. A heavy bulldog stepped toward him and began licking the bottom of his jeans. Thick-necked, pug-nosed and gentle, the dog’s flat tongue maneuvered like a separate animal. The bulldog looked up at him, grunted or sneezed, then turned to enter Caffé Vita. Its owner nodded as he followed the dog in. Vin wondered whether he knew either of them in this world.

“What do you know about the crèche?” he asked Bill.

“Did you use it again? You said you were done with it. You said when you came out your cat had disappeared, along with her scratching post, all her cat food and her dishes. Sophie, I think you said. You were freaked out.”

“And that was all?”

Bill laughed. “Yeah. But that seemed like enough, right? You said you liked that cat.”

“I did. I miss her.”

“Okay, but like I’ve said every time you bring her up, you never had a cat. Right? That thing has bad mojo, man. Really bad. I think you should turn it over to the university. You’re never going to figure it out on your own and you have the money from Sigmoto. It’s not like you need the house.”

“No. I probably know everything I need to know about it.”

“See you in a little bit?”

“At the Space Needle’s elevator. Sure.”

“Yeah. Okay. And, hey, I’m glad you called. You know, that you reached out. I know how hard you and Hanna tried. I know how hard things must be for you right now. You’ve never really wanted to talk about this stuff though. Like I said, I’m glad you called.”

“Thanks Bill.”

“Oh, and hey, I saw Kim this morning. She told me to say hi.”

There was a pause before Vin managed to say, “And, how’s she?”

“Great. That paper she coauthored? It got accepted. Her first publication. I bought her a new pen and a scientific notebook to celebrate.”

He walked west on Roy Street, aiming by default toward what he still thought of as Nerdean’s house. He had mumbled something to Bill and hung up, ending their conversation, too stunned to keep talking. Wasn’t this what he had wanted for years—all three of them alive, and Bill healthy? But what did he and Kim mean to each other now, in a new world where they were barely friends?

He wouldn’t go back into the crèche, at least not anytime soon, but not because Kim and Bill had both survived here. Trina was still missing. Living in the same world as his daughter was what he wanted. But he didn’t believe he could find her without destroying himself and possibly her, and he wanted a life, whatever that might mean. His feelings might change or they might not but for now, knowing what he wanted was enough.

At Counterbalance Park, sunlight was soaking into the teak decking and warming it so that steam rose in thinning spirals. The air was fresh, cleansed by the recent rain. Gray and rose canyons and bright buttes of cloud drifted above.

He decided not to go directly back to the big house. Instead, he turned up the hill, walking fast so that he ran short of breath and felt his body laboring. In this world, he hadn’t taken very good care of himself.

The sun held out all the way to the top of the hill and then the day cooled as he turned toward the park and the daylight turned blue-gray. What are the forces that transform a person? What makes one thing possible and another impossible and what moves those limits? Beyond the obvious, what was now out of his reach and what was within it?

The house across the street from the West Queen Anne Playfield looked to him exactly as it had when he and William left it, only a few hours before and years ago. But this wasn’t the same world, and that wasn’t really the same house and Vin didn’t know what to expect. Ghosts? Or violence? Ordinary people with unanswerable questions? He walked up the broad concrete stairs and turned left before the wooden porch, walked to the side of the house with the dull white door at ground level. Blackout curtains like he remembered at William’s place. He knocked twice but no one answered. He waited and knocked again.

He decided to try the upstairs apartment. The owners, or whoever rented up there, might know where William was. He stepped onto the lawn and had another moment of panic, stood breathing and watching small birds in a large chestnut tree.

The front porch was spacious and clean, the paint recent. He walked up and pressed the doorbell and waited. A thin woman in her late sixties answered.

“Hello, Vin,” she said. “How can I help you?”

And so here it was again, a question, what are your intentions? What do you mean? And once again, Vin wasn’t sure. His mind was completely quiet. There were no words to borrow, no voices speaking through him. He could imagine responding in any number of ways and he tilted his head as he thought about the fact that he might not understand what she was asking, which could mean he was overthinking things.

He took a breath and glanced over his shoulder toward the green park across the street. He was an animal in a world somewhere, on a white porch, facing a similar creature. And she was waiting for him to say something. All of his questions remained and all of life lay before him. He answered.