For Italians during the first great wave of immigration to America, family would be their source of strength and survival, but the values that sustained them in places like Roseto, Pennsylvania, would also put them at odds with the rest of the country. Roseto’s residents—like Italian Americans elsewhere—tended to wall themselves off, mistrusting outsiders and outside institutions. That self-imposed isolation made it harder for them to assimilate into mainstream American life.

The instinct to trust only the family—to believe, as parents routinely told their children, that “blood is thicker than water”—is deeply rooted in the complex history of Italy, a land invaded and conquered for thousands of years and occupied by foreign countries well into the nineteenth century. This fractured history distinguishes and separates the Italian experience from all the rest of southern Europe.

The nearly century-long project to unite Italy began after the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and was completed with the annexation of Rome from the Papal States in 1870. But even after unification, the land and people of the north and the south couldn’t have been more divided, geographically and culturally. The north offered a landscape of undulating copper hills, suitable as background to the images of fine-boned ladies in Renaissance portraits, and boasted unparalleled achievements in art, architecture, and literature.

By contrast, Italy south of Rome, known as the Mezzogiorno (literally, “midday”), was a dusty, arid land where illiterate peasants slavishly toiled for aristocratic landowners. About 85 percent of the Italians who came to the United States were from southern Italy. The bleakness of the region was immortalized in the Italian writer Carlo Levi’s book Christ Stopped at Eboli, whose title comes from a peasant saying that Christ could not have traveled any farther than the fertile land of Eboli, which lies south of Naples in the region of Campania.

Unlike the lush northern terrain, the south of Italy was an arid land where peasants slavishly toiled.

A twentieth-century Italian parliamentary investigation revealed that the wages of peasants had remained the same since 1780.

“We’re not Christians,” the peasants told Levi. They meant that they were not “human beings”; they were too far below the status of the blessed. Levi was banished in 1935 to a small town in Basilicata, then known as Lucania, because of his opposition to Fascism. The government’s decision to exile its opponents to the south is a stark reminder for Italian Americans that the bleak, impoverished life of their ancestors was barely a step above imprisonment in the minds of northern Italians.

“No one has come to this land,” wrote Levi, “except as an enemy, a conqueror, or a visitor devoid of understanding. The seasons pass today over the toil of the peasants just as they did three thousand years before Christ; no message, human or divine, has reached this stubborn poverty.” Indeed, an Italian parliamentary investigation in the early twentieth century revealed an extraordinary fact: the wages of peasants had remained the same since 1780.

But in the mid-nineteenth century, southern Italian peasants—especially those from Sicily, considered the most revolutionary area of the country because of its extensive poverty—were holding out some hope for change. They placed their faith in a leading figure of Italian unification, the indefatigable soldier Giuseppe Garibaldi, to restore justice to their land.

The unification of Italy was Garibaldi’s lifelong passion. As a young man, Garibaldi was largely influenced by the writings of the Italian radical thinker Giuseppe Mazzini, and he joined Mazzini’s secret revolutionary group, Young Italy, which sought to liberate citizens from rule by kings. After being condemned to death in absentia for taking part in a Mazzini-inspired revolution in Genoa, at twenty-eight Garibaldi sailed to South America. He remained there for over a decade, leading the Italian Legion fighters during Uruguay’s war with Argentina, and receiving military training that would be essential to his guerilla battle for Italian unification. Although he was exiled from Italy several times, Garibaldi always managed to find a way back, and most of his life consisted of a series of seemingly hopeless battles with an ill-supplied, ragtag army of Italian volunteers dressed in red shirts, throwing bayonets in the face of enemy bullets, or carrying rifles that, more often than not, refused to fire.

Garibaldi was one of four main players of Italian unification in the mid-nineteenth century, charting a course by rallying his vagabond army and trying to work with men who mostly detested each other—the revolutionary thinker Mazzini, the unpredictable monarch Victor Emmanuel II, and the scheming prime minister Camillo di Cavour. To add to the complexity of the quest for national unity, both Victor Emmanuel and Cavour, products of Austrian and French culture in the north, struggled throughout their lives to speak the Italian language.

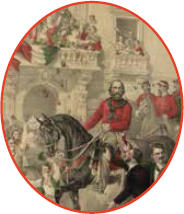

In 1860, Garibaldi decided to lead his army, known as the Red Shirts or the “Thousand” (technically there were 1,089 volunteers), to Sicily to defeat the Bourbons, a dynasty that had originated in France and now ruled Italy’s southern provinces. It was a bold move that may have been based on faulty information about a peasant insurrection in the provinces, which in reality had been suppressed. But a combination of Garibaldi’s shrewd military skill and some extraordinary good luck created a scenario that ultimately led to the capture of Sicily and the defeat of twenty-five thousand Neapolitan troops under Bourbon rule.

After the Thousand won an astounding victory in the town of Calatafimi in Sicily, Garibaldi advanced his troops to Palermo. He thought that his only means of defeating the huge Bourbon army depended on getting his men into Palermo undetected and inciting the peasant population to revolt. It was a gamble based on the fact that not a single member of the peasantry in the north or the south had ever joined his nationalist cause. “I wish from my heart,” wrote Garibaldi about the Thousand in his memoirs, “that I could have added ‘and of the peasant’” to the list of the bricklayers, carpenters, cobblers, engineers, lawyers, and students who joined his army. “But I will not distort the truth. That sturdy and hard-working class belongs to the priests, who keep them in ignorance. There was not one case of them joining the volunteers.”

But in Palermo, a different picture emerged. After his victory in Calatafimi, thirty miles away, the people of Palermo rose up in revolt. The peasants emerged from the streets and piazzas bearing knives and daggers. The women—“awe-inspiring,” in Garibaldi’s words—hurled mattresses, chairs, and furniture from their windows to form barricades against the Neapolitan troops trying to enter the city, and some even poured pots of boiling water on the soldiers who had found their way in.

Garibaldi’s ultimate victory meant that the old Kingdom of Sardinia would become the new Kingdom of Italy, with Victor Emmanuel made its ruler in 1861. The final pieces of this unification, called the Risorgimento, would still take another ten years to put into place. The populist Garibaldi had promised to carry out land reform immediately, but the new monarch preferred to keep the power in the hands of property owners. Conditions deteriorated even further after Garibaldi, who served as the temporary “dictator” of Sicily, introduced two highly unpopular measures: new taxes and a military conscription. Now the peasants, with barely enough food to live on, had to dig deeper into worn pockets to pay taxes that would rise by more than 50 percent. They also had to watch their boys leave home to join a military and defend a country that seemed as foreign to them as the divided land from before.

The peasants were unwilling to join Garibaldi’s nationalist cause until he reached Sicily.

Italian peasant girl, 1861.

The Austrian Prince Klemens von Metternich’s famous line that Italy was “only a geographical expression” certainly was borne out in the life of the peasants who spoke a regional dialect, knew little beyond village life, and never thought of themselves as “Italian” or had the time to daydream about any nationalist cause. They didn’t even know the word Italia, with many believing that “La Talia” was Victor Emmanuel’s wife. And how could the peasants wave a flag for patriotism without political say? Only about 5 percent of the male population was allowed to vote. To add to the unfairness, the south paid more in taxes, as a percentage of its wealth and economic output, than the north but received less in government aid and services. The belittlement of southerners by northerners—still acutely felt in parts of Italy today—first blossomed after unification, when the north had to pay more attention to its new brethren. “What barbarism!” declared Italian statesman Luigi Carlo Farini after visiting the south. “This is not Italy! This is Africa.”

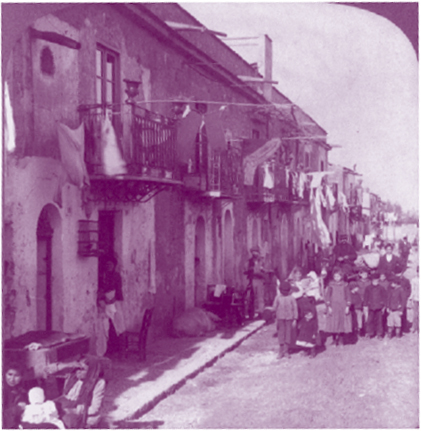

By 1880, a decade after a fully unified Italy, southern Italian peasants could barely survive. In cities and countryside, unemployment, crime, disease, and squalor had become unbearable; the lack of food and money even left some women scraping plaster off their walls to mix into dough in order to stretch the bread supply. These brutal conditions meant that the peasants became even more distrustful of outside authority. The state was seen only as the entity that robbed you of the meager amount you tried to save. “What could they possibly put a new tax on?” wrote Ignazio Silone about peasant life. “Maybe a tax on moonlight?”

Daily life also became much more dangerous: as tax revolts spread throughout the south, local brigands took advantage of the turmoil, wreaking havoc on the land by attacking farms and killing livestock. The government responded by imposing a military law that led to arbitrary arrests and executions. Garibaldi, long dispensed from his duties and discarded by those in power “like an orange peel,” described his disillusionment: “The outrages suffered by the people of Southern Italy cannot be quantified. I am convinced that I did nothing wrong, but despite that today I would not take the same route in Southern Italy as I would fear that I would be attacked by stones, because the result was only squalor and hatred.”

Under the miserable conditions they had to endure, southern Italians began to hear and to heed the call to America.

Under these untenable conditions, southern Italians began to hear and to heed the call to America—one that would bring five million people in the course of a century. Word spread throughout isolated villages about those brave enough to leave. American companies put up posters in villages promising pots of gold, state governments recruiting workers sent out leaflets announcing work opportunities, and letters from the earliest migrants beckoned those left behind to cross the ocean. The Italian government tried to discourage emigration, because large landowners needed the peasantry to work the land.

At the end of the nineteenth century it became clear that Garibaldi’s dream of a united country had helped to spur its greatest exodus, with the population heading to other countries around the world. By 1905, over seven million people had applied to migrate; it is estimated that the country lost more than sixteen million people between the 1870s and the early 1920s. Trust no one outside the family, and concomitantly, invest all your precious resources in the family, became the credo that southern Italian peasants would bring to America and choose to live by.

In a tiny cottage in Staten Island, New York, home of the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum, the cherished symbol of Italian unification—the red shirt—hangs behind glass. The curious choice for a uniform—the bright color announced itself to the enemy like a modern-day traffic light—can be traced to Garibaldi’s days in Uruguay, when he led the Italian Legion in 1843. The government, wanting to skimp on the costs of uniforms, found boxes of red overalls intended for Argentine cattle-slaughtering houses, the color blending with the gory work. Garibaldi liked wearing the loose-fitting tunic and decided to make it the uniform of his volunteer Italian army, earning them the moniker “Red Shirts.” In the nineteenth century, fashion-crazed aristocratic British women infatuated with the iconoclastic Italian began wearing the shirt, a version of which hangs in Staten Island and marks Garibaldi’s time living in exile there—one of the stranger interludes in his storied career.

After Garibaldi failed to take back Rome from papal domination in 1849, he fled north, pursued by the French, who had helped to protect the pope, and then by the Austrians. With hostile forces surrounding him, Garibaldi had to escape Italy, but his pregnant wife, Anita, who had left their other children with relatives so that she could fight with Garibaldi, became mortally ill as they marched through Tuscany and over the Apennines. Garibaldi’s eventual exile to America—where friends had urged him to go—followed a huge military defeat, a perilous lengthy escape, and the sudden death of his wife.

Garibaldi’s friend Antonio Meucci gave him lodging in his Staten Island cottage, but the great military hero of Italian unification could not stand to be idle or a freeloader. Instead, he persuaded Meucci to open a sausage factory that could employ him and other poor Italian refugees. (Imagine an unemployed General Ulysses Grant flipping hamburgers.) The enterprise was a financial failure, however. Meucci, a better businessman than Garibaldi, soon closed the sausage factory, starting instead a candle factory on his property. Garibaldi was also quite useless at the task of making candles, which required a particular agility in dipping the wick into the tallow. And Meucci, appalled that the famous freedom fighter was performing menial labor along with the impoverished refugees, tried to stop him from working—a move that drove Garibaldi deeper into despair.

Garibaldi found some satisfaction in helping poor refugees, and one day an Italian man came by and asked Garibaldi for a shirt, explaining that he was penniless. Garibaldi told the man that he had only two shirts: the one he was wearing and another in the laundry. Then he remembered that his trunk held the red shirt he had worn in the battle for Rome. At this point Meucci protested, saying that Garibaldi should not give away such a valuable item. Meucci gave the man one of his shirts instead and preserved Garibaldi’s, which, according to local lore, is the shirt that hangs in the museum today.

After his astounding victory in Sicily, Garibaldi wore the red shirt for the rest of his life, cementing it as a lasting symbol of a unified Italy. In 1881, eleven months before his death, Garibaldi amended his will to request that he be cremated in a red shirt.

FROM CARLO LEVI’S

CHRIST STOPPED AT EBOLI

Carlo Levi was an Italian Jewish writer, doctor, and painter. Levi’s book Cristo si è fermato a Eboli (Christ Stopped at Eboli) described the time he spent in exile for his anti-Fascist beliefs. The Italian government sent Levi to the town of Aliano, called Gagliano in the book, in the province of Lucania (now known as Basilicata), once the poorest region in Italy. The book was a wake-up call to northerners about the centuries-long plight of southern Italian peasants. The town of Matera—described in the following excerpt by Levi’s sister, a physician who came from Turin to visit him—was so poor that many of its residents lived in caves carved into the mountains. Today the area has been declared a World Heritage Site, and some of the grotto homes have been converted into luxury hotels. About twenty-five miles south of Matera, in the town of Bernaldo, the Italian-American filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola opened a luxury hotel in 2011 in honor of his paternal grandfather’s birthplace.

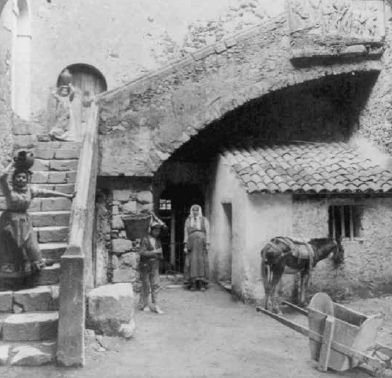

The houses were open on account of the heat, and as I went by I could see into the caves, whose only light came in through the front doors. Some of them had no entrance but a trapdoor and ladder. In these dark holes with walls cut out of the earth I saw a few pieces of miserable furniture, beds, and some ragged clothes hanging up to dry. On the floor lay dogs, sheep, goats, and pigs. Most families have just one cave to live in and there they sleep all together; men, women, children, and animals. This is how twenty thousand people live.

Of children I saw an infinite number. They appeared from everywhere, in the dust and heat, amid the flies, stark naked or clothed in rags; I have never in all my life seen such a picture of poverty. My profession has brought me in daily contact with dozens of poor, sick, ill-kempt children, but I never even dreamed of seeing a sight like this. I saw children sitting on the doorsteps, in the dirt, while the sun beat down on them, with their eyes half-closed and their eyelids red and swollen; flies crawled across the lids, but the children stayed quite still, without raising a hand to brush them away. Yes, flies crawled across their eyelids, and they seemed not even to feel them. They had trachoma. I knew that it existed in the South, but to see it against this background of poverty and dirt was something else again. I saw other children with the wizened faces of old men, their bodies reduced by starvation almost to skeletons, their heads crawling with lice and covered with scabs. Most of them had enormous, dilated stomachs and faces yellow and worn with malaria.

The peasants described the south of Italy to Carlo Levi as the place where Christ forgot to stop.