A mob lynching of Italians in Tampa, Florida.

After Garibaldi’s astonishing military success in Sicily, word of his skills traveled across the Atlantic, and President Lincoln tried to recruit the Italian general for a major post in the Union army. The State Department sent an envoy to Garibaldi’s home on the island of Caprera, but the encounter proved fruitless when Garibaldi insisted that he be appointed commander in chief with the power to immediately abolish slavery. Never mind that the president of the United States was commander in chief of the army. As Garibaldi knew, Lincoln was a moderate who didn’t initially advocate the full abolition of slavery, but only opposed the extension of slavery into new territory. Lincoln needed the continued support of several southern states, and he had been arguing that the war was about preserving the union, not abolishing slavery. The envoy spent the night on Caprera and tried again the next morning to convince Garibaldi to fight for the North’s commitment to democracy and constitutional government, but Garibaldi remained absolute in his position and the offer was rescinded.

After the Civil War ended in 1865 and Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation could be fully implemented, the people replacing the freed African-American slaves who had toiled on sugar and cotton plantations were—ironically, given Garibaldi’s lecture in Caprera—southern Italian immigrants, mostly Sicilians. They began arriving in the port city of New Orleans looking, in their words, for pane e lavoro, “bread and work.”

There were two entry points for European immigrants coming to America—New York and New Orleans—and the state of Louisiana worked hard to recruit Sicilians to its port, then the second largest in the nation. The plantation owners were desperate to replace the slaves and unhappy with the demands of some African Americans who stayed on as tenant farmers. At first they tried, but failed, to attract white American farmers, as well as Chinese immigrants, who were more interested in working in the fishing industry. In 1866, the state of Louisiana formed a Bureau of Immigration and sent propaganda-filled pamphlets to Europe about opportunities on plantations. They already had some experience working with Sicilians because New Orleans imported citrus from Palermo, and Sicilians were also the only group that responded en masse to their efforts.

By successfully recruiting Sicilians, the state and plantation owners found the right match: southern Italians were used to the cyclical nature of planting, tilling, and reaping under a burning sun and willing to work around the clock. The immigrants were desperate to earn enough money to send home or, in their biggest dreams, to own a small piece of land. Here they would find better conditions than in Italy, despite the brutal nature of the work.

Even the leading advocate for disenfranchised former slaves, Booker T. Washington, noted that conditions for the southern Italian peasant were worse than for the African-American tenant farmer. After visiting southern Italy, he wrote, “I have described at some length the condition of the farm labourers in Italy because it seems to me that it is important that those who are inclined to be discouraged about the Negro in the South should know that his case is by no means as hopeless as that of some others. The Negro is not the man farthest down. The condition of the coloured farmer in the most backward parts of Southern States in America, even where he has the least education and the least encouragement, is incomparably better than the condition and opportunity of the agricultural population in Sicily.”

From planting, to harvesting, to cutting and then grinding the cane, the work in Louisiana was backbreaking, but the Italians were up to the task. Growing the cane was a laborious process because the fields needed continuous irrigation and drainage to ensure that the roots wouldn’t get too wet and rot. Cutting the cane later in the season meant working sixteen to eighteen hours a day, seven days a week. The Italians often labored side by side with black tenant farmers—and to the surprise and anger of southern whites—also socialized with them. They received the same wages as blacks: seventy-five cents to a dollar a day. Because the peasants had always managed to miraculously grow crops on arid land, the plantation owners were both astonished and delighted by their tireless labor and productivity working on more fertile soil.

Thousands of Sicilians began to head to Louisiana, and from the late 1800s to 1924, over a hundred thousand Italians arrived in the Port of New Orleans. Many worked seasonally and headed north for the rest of the year, but an estimated thirty thousand made New Orleans or the Louisiana parishes their home.

Plantation owners hoped that this cheap labor supply would last forever, but Italians, believing in the promise of America to improve their lot, resented working so hard for so little. They discovered that New Orleans and the Louisiana delta offered more opportunity, and they found jobs there peddling fruits and vegetables, handling cargo on the docks, and working in the fishing industry.

The Italians who settled in Louisiana found opportunities in New Orleans peddling fruits and vegetables.

Many settled in the historic market section of New Orleans. The French Quarter began to be called Piccolo Palermo. While Sicilians represented a quarter of all Italians who came to United States, in Louisiana they made up approximately 90 percent of the Italian population. The immigrants lived in appallingly crowded conditions and tended to stick together, displaying in the New World their historic distrust of outsiders. Meanwhile, the southern establishment was both disturbed by the onslaught of poor, olive-skinned Sicilians and resentful of the success of a few. Southerners in positions of power were also concerned about the newcomers’ growing influence in local politics.

In this climate of suspicion, a crime took place that would alter and damage the community’s relationship with Italians well into the middle of the twentieth century.

On the night of October 15, 1890, the popular police chief of New Orleans, thirty-two-year-old David Hennessy, was returning home late at night with a former colleague. They stopped at a saloon for a snack of oysters, and the two parted ways as Hennessy headed to the home that he shared with his mother. A few minutes later a group of men opened fire on the police chief. Hennessy pulled out his gun and fired back, but his efforts were in vain. His friend, hearing the barrage of gunfire, ran back to the dying Hennessy, who allegedly told him, “The dagos shot me.”

The next day, the mayor of the town, Joseph A. Shakespeare, issued this order to his police department: “Scour the whole neighborhood. Arrest every Italian you come across if necessary, and scour it again tomorrow morning as soon as there is daylight enough. Get all the men you need.”

New Orleans’s popular police chief, David Hennessy.

The crime story would never be solved. Its interpretation over the years depended on who told the tale. The court documents have been lost, so the only records are the media reports that reflect the bias of the time. To the white establishment, the crime was about the growing influence of the Sicilians and a shadowy organization called “the Mafia” that they were establishing in New Orleans. Most media outlets mimicked this thinking, and it wasn’t until many decades later that criminal justice experts and journalists revisited the material and put forth other theories.

A persistent American myth, with roots in this New Orleans crime, is that the Mafia is an ancient Italian organization, highly unified and dating back to as early as the twelfth century. Scholars who have studied the Mafia explain that the word mafia, in existence probably as far back as the seventeenth century, originally connoted a form of criminal behavior, not an organized group. In the anarchy after unification, a mafioso was considered an uomo di rispetto (“man of respect”) who, in the absence of law and order, upheld honor, tradition, and peasant interests and resorted to violence in order to do so. Eventually, one man would achieve dominance in a village and then form associations with family and friends, who composed a cosche (literally, “the leaves of an artichoke”) for their territory. In this agricultural society, latifundia were the large estates throughout Sicily owned primarily by absentee landlords and run by gabellotti, estate managers exploiting the peasants who toiled the land. The gabellotti hired members of a mafia (or sometimes themselves were mafiosi) for a twofold purpose: to keep the peasants in line, and to acquire more lenient terms from the absentee landlord to rent the properties.

The local Mafia was involved in a range of both legal and illegal activity, and it wielded power by making clear that brutal violence would be used to achieve its ends. The Mafia’s presence created a kind of alternative society, parallel to the feeble government; and eventually, the Mafia controlled elections, installing its own people and determining affairs—or at least calling for favors—not only in Sicily but also in Rome. The Mafia also managed the roads and water—charging taxes on these essential aspects of life—and took over the town’s commerce, dominating fruit and vegetable markets. While flourishing in lawless Palermo and western Sicily, the Mafia was virtually absent from eastern cities such as Messina and Catania, where industry provided better opportunities and landlords tended to live on their estates rather than renting to unscrupulous gabellotti.

The word mafia was added to the American lexicon after the New Orleans murder of David Hennessy.

Since Italian immigrants first came in great numbers to the United States, Americans have imagined that what in Italy was a loose-knit organization, composed of about a dozen members in each town, was transformed here into a highly unified criminal society. This bias immediately became clear after the shooting of David Hennessy. Town people linked the murder to his involvement in a fight between Italian stevedores, two rivals named Provenzano and Matranga, who handled fruit cargo. Each wanted control of the lucrative docks, but while the stevedores were certainly thuggish characters, it’s unclear whether they had any ties to Mafia criminals in Sicily. The bitter rivalry led to a shootout in which Matranga was wounded, and members of the Italian business community immediately went to the police both to press charges and to testify in court (a response typically considered “American,” not the actions of Mafia men bound by a code of honor and distrusting the government). During that trial, people accused the police and Hennessy of protecting the Provenzano clan, and because of his involvement, some claimed later that Hennessy had been shot in revenge.

The rosy portrait of Hennessy after his death was that of a man of uncompromising ethics and civic virtue, but this, too, seems to be a myth in a sordid New Orleans tale. The city was a cesspool of vice and corruption, and even David Hennessy had landed in jail before becoming police chief. He and his cousin Mike had had an ongoing feud with a rival officer competing for promotions and, after being arrested for shooting and murdering the officer, they served prison time until a jury decided that they had acted in self-defense. It was also unclear why, if the white establishment considered both the Provenzanos and the Matrangas “mafiosi,” David Hennessy had testified on behalf of the Provenzanos in court.

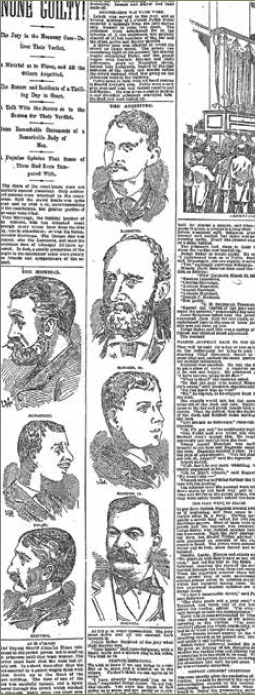

After Mayor Shakespeare’s call to “arrest every Italian,” 120 were rounded up—cobblers, fruit sellers, laborers, night watchmen, even a twelve-year-old student—and some were badly beaten. Ultimately, nineteen men, mostly associates of the Matrangas, were arrested, and nine were brought to trial. During the hysteria of the next four months, the press routinely publicized the prosecution theory that these men were part of a secret Italian society known as the Mafia. New Orleans’s Daily Picayune reported that the trial was a “war between American law and order and Italian assassination.” The case received national attention, and as far away as Chicago, Italian Americans contributed to a defense fund.

Finally, following much conflicting evidence and testimony, the jury cast a verdict of “not guilty” for six of the men and failed to reach one for the other three. The shocked judge refused to let the men go free and ordered them to return to the parish prison that night. Outraged community leaders didn’t believe the jury’s explanation of reasonable doubt about a crime committed in the dark without eyewitnesses and alleged that the jury had been paid off. They quickly organized a mass meeting calling all citizens “to take steps to remedy the failure of justice in the Hennessy case. Come prepared for action.”

The next morning, thousands of people headed to the square, and a lawyer and rally leader named William S. Parkerson exhorted, “When the courts fail, the people must act! What protection, or assurance of protection, is there left us, when the very head of our police department, our chief of police, is assassinated in our very midst by the Mafia Society, and his assassins are again turned loose on the community.”

The masses were furious and whipped into action. When another meeting leader, John Wickliffe, asked whether the crowds would follow him to the jail to vindicate this crime, they shouted back, “Yes! Hang the dago murderers!” The crowd asked if they should get their guns, and Parkerson told them to do so immediately.

Parkerson and Wickliffe considered themselves reformers trying to fix a corrupt system—and indeed the New Orleans political system was deeply corrupt. But at the time, the “reform” movement also consisted of white separatists, like both of them, working to take away the vote from blacks. These men feared that the underclass would take control, and they were concerned about the Sicilians’ gaining positions in local politics, believing that the Italians would poison the American political system with their nefarious Mafia organization.

With calls to “hang the dago murderers,” the masses assembled outside the parish prison.

That Saturday morning they rallied a crowd of over eight thousand people, many of them now armed. The mob marched to the jail, quickly overtook the prison wardens, and stormed the gates. The acquitted Italians tried to hide, crouching under benches and behind posts, but the mob riddled them with bullets while shouting, “Death to the dagos!”

The crowd waiting outside the prison wanted a piece of the action too, so Parkerson delivered two men to them. Both had been wounded and could now be lynched by the mob. They were hung from a lamppost and tree, their dying bodies dragged, kicked, and beaten with sticks and canes. Men carrying rifles and shotguns continued to pump them full of bullets; some even used their bodies for target practice. At the end of that bloody day, eleven Italians had been murdered and lynched, and the organizers told the cheering crowd that it had done its civic duty by ridding New Orleans of thugs and murderers.

The next day the New York Times headline announced “Chief Hennessy Avenged.” The paper’s editorial read, “These sneaking and cowardly Sicilians, the descendants of bandits and assassins, who have transported to this country the lawless passions, the cut throat practices and the oathbound societies, are to us as a pest without mitigation.” While it continued that “orderly and lawabiding persons will not pretend that the butchery of the Italians was either ‘justifiable or proper,’” the editorial concluded, “it would be difficult to find any one individual who would confess that privately he deplores it very much.”

The effect of the lynching on the Italian-American community in New Orleans was profound. Many had been bullied since the start of the trial, leading them to quit their jobs in New Orleans or head back to Italy. When ships from Italy arrived packed with thousands of immigrants, they were taunted and jeered. The Italian government was furious over the treatment of men who had been acquitted by a jury, and diplomatic relations were strained for over a year. The wound festered after a grand-jury report exonerated the actions of the mob, describing its members as “several thousand of the first, best and even the most law-abiding” citizens. The press continued to sensationalize the story and frighten Americans, writing that the United States was on the verge of a naval war with Italy. Diplomatic relations were restored only after the US government agreed to pay a small reparation to some of the families of the murdered men—an action denounced by Congress.

The trial over the murder of David Hennessy and the New Orleans lynching painted a portrait of Italian-American immigrants not only as poor and downtrodden, but as the dark-skinned “other”—born criminals, violent and primitive in nature. After the New Orleans lynching, the press began to routinely describe any crime committed by Italians as Mafia activity. The Italians of New Orleans, once eager to come to this land to escape the unending cycle of poverty and desperation, were cast together under a net of criminality. They were among the first victims of a troubling and persistent American tendency to target entire immigrant communities for the crimes of the few.

The parish prison after the lynchings.

The community never failed to remind Italian Americans of their presumed guilt over the murder of the city’s police chief. One taunt, mimicking the Italians’ broken English, began at the time of the trial and persisted for decades. Whether posed to a schoolchild desperate to assimilate into the mainstream or to a shopkeeper trying to earn a living, the question, designed to keep the ethnic group in its place, was always the same: “Who killa da chief?”