A laceworker and her family in East Harlem. By 1910, over a half million Italians lived in New York City, and East Harlem became their largest enclave.

A laceworker and her family in East Harlem. By 1910, over a half million Italians lived in New York City, and East Harlem became their largest enclave.

A nine-year-old boy named Leonardo Coviello felt the weight of responsibility during an interminable train ride to Naples with his mother and younger brothers, the first step of their arduous passage to America. His mother tried to remain strong when fierce waves threatened to submerge their ship, but upon reaching Ellis Island she could no longer contain her fear. Guards led the boys to another area for a physical examination, and their mother panicked. On the boys’ return, her obsessive clutch and empty gaze revealed the terror of a woman who had believed the separation permanent, and signaled to Leonardo the toll this journey had already taken on her. After spending two days in Ellis Island before their discharge, mother and boys sleeping on hard benches, they finally reunited with Leonardo’s father, who had been working and waiting for them in New York.

The mountain air and piercing sun of their village of Avigliano in Basilicata soon vanished to memory, replaced by the duller light of the urban skyline and the odoriferous, garbage-filled East River. They joined other tenement dwellers in East Harlem, packed together in their shabby building with one shared toilet for the entire floor. His mother, whose sorrow of leaving Italy would never dissipate, enjoyed one luxury—water from the tap, which she always treated as a wonder. Leonardo’s little bit of wonder was a chocolate cream that sweetly coated his tongue—the first candy he had ever tasted after his homeland’s confetti, sugarcoated almonds.

The Coviellos, like so many others from southern Italy, took part in a mass exodus to pursue the dream of America. In the first decades of the twentieth century, one-third of all southern Italians left the “land that time forgot,” and by 1919 over three million people had arrived here. In New York City the number of Italian immigrants rose from 545,000 in 1910 to 807,000 by 1920. The city was now home to one-quarter of all foreign-born Italians in the nation, and East Harlem became the largest Italian-American enclave in New York City.

Leonardo’s father labored as a handyman when he could find jobs, his wages amounting to about seven or eight dollars a week. Everyone they knew struggled to survive; much of the available work was sporadic or seasonal, and fatalism draped households like the dark peasant shawls covering and separating the women from more modern Americans. La volontà di Dio!—it’s God’s will whether one can find work and put food on the table. Many first-generation immigrants soon abandoned the dream of transcending the life of poverty to which they had been born; the hope for a future without sweat and tears became the domain of their children.

In the Coviello family, the wager worked out. The young boy would eventually graduate Phi Beta Kappa from Columbia University, earn a PhD from New York University, teach students like future congressman Vito Marcantonio, and lead a public high school that met the needs of immigrant children better than most schools in the city. But along the way, he learned the bitter tug-of-war of loyalty between his family and his new country.

The lesson began soon after Leonardo started public school. He came home one afternoon with a bag of oatmeal given to him by his teacher, who had told Leonardo to prepare the mixture for breakfast to better meet the mental demands of the school day. Observing that Italians were shorter and skinnier than Anglo-Saxon stock, progressive teachers and social workers offered nutritional suggestions to correct what they considered the result of poor nutrition.

But to an Italian family, hardly a greater insult existed than being told how to eat. Leonardo’s father, examining the oatmeal and testing it with his fingers, decided that the bran resembled nothing more than pig food. “What kind of school is this?” his father shouted. “They give us the food of animals to eat and send it home to us with our children! What are we coming to next?”

Rolling pin and ravioli cutter. For people accustomed to making fresh pasta, no greater insult could be offered than instructing them in what to eat.

Well-intentioned gifts of “pig food” sent home were not the only way the Italians felt put upon and insulted. Protestant social workers arrived at the peasants’ homes to offer instructions on the intimate matters of keeping house and raising children. They talked about the need for fresh air, opening wide the windows, to the torment of the Italian mother who feared nothing more than a draft sickening her baby. They countermanded generations, perhaps millennia, of cultural practice by telling mothers not to swaddle their infants because it was best to let the limbs move freely.

If the immigrants recoiled in anger, the children shrank in embarrassment over their parents’ dress and speech. The message to the second generation became clear: the American system is far superior to your strange and mystical Old World families and their hard-to-pronounce vowel-ridden names.

The young Leonardo again experienced the dual pain of betrayal and shame when he took his report card home and asked his father to sign it. “What is this?” the father asked. “Leonard Covello! What happened to the ‘i’ in Coviello? . . . From Leonardo to Leonard I can follow . . . But you don’t change a family name. A name is a name. What happened to the ‘i’?” Leonardo responded matter-of-factly that his teacher, the eponymous Mrs. Cutter, couldn’t pronounce Coviello so she snipped off the “i.” His father replied, “And what has this Mrs. Cutter got to do with my name?”

Protestant social workers offered instruction on the intimate matters of keeping house and raising children.

The boy, secretly grateful that the teacher had made his name sound less foreign, couldn’t understand his father’s ire. His father, shrugging in resignation, finally signed the report card, but the matter hissed like a steaming pot of espresso as his mother joined in. “A person’s life and his honor is in his name. He never changes it. A name is not a shirt or a piece of underwear. You must explain this to your teacher. It was a mistake. She will know.”

“It was no mistake,” he replied. “On purpose. The ‘i’ is out and Mrs. Cutter made it Covello. You just don’t understand!”

“I don’t understand. I don’t understand. What is there to understand? Now that you have become Americanized you understand everything and I understand nothing.” But his mother’s pleas were fruitless; from that point forward Leonardo Coviello would be known as Leonard Covello.

The personal pressure Leonard experienced in elementary school to become American accompanied a growing political concern: lawmakers fretted about the kind of stock entering the country. After 1900 the US government required that every individual who came through Ellis Island be categorized by race. For Italians, this meant that the immigration official marked down whether they were from the north or south, Alpine or Mediterranean, stamping their arrival with the distinction of superiority or inferiority—“high” Italian, from the cradle of civilization, or “low” Italian, from the cauldron of criminality. But the official demarcation of the Po River, instead of Rome, as the dividing line between north and south was an odd one, making even a person from Florence a “southerner.”

Some Americans began to refer to all southern Italians as “Sicilians,” and Sicilians, who represented one-quarter of the Italian immigrants who came to this country, carried much of the burden of the American prejudice. Their skin color tending a shade more olive, their hair a little kinkier than other southernersʼ, they began to represent the new dark “other” affiliated with the Mafia, the Black Hand, and la vendetta.

Back in Italy, a country still grappling with the ramifications of the Risorgimento, a nativist urge to label the southerner as inferior was also taking place. Before unification, northerners had practically no contact with the south, but now they were witnessing the chaos, banditry, and disarray of a supposedly unified country. An Italian sociologist named Alfredo Niceforo published a study in 1900 on what was being called the Questione Meridionale (“southern question”), and his ideas added to the growing assumption of racial inferiority. Niceforo wrote, “One of the two Italies, the Northern one, shows a civilization greatly diffused, more fresh, and more modern. The Italy of the South shows a moral and social structure reminiscent of primitive and even quasibarbarian times, a civilization quite inferior.”

An Italian family in Rhode Island. Some Americans began to refer to all southern Italians as “Sicilians.”

One of these two Italies widely embraced Niceforo’s study as a “scientific” anthropological work, while the other half fumed, rejecting the notion of an innate inferiority. Niceforo’s work would reverberate in America too, echoed and endorsed by sociologists and early-twentieth-century eugenicists. As an educator, Leonard Covello pointed out how Niceforo influenced academics looking for “proof” of their own prejudice. A case in point was Edward Alsworth Ross, an American sociologist and professor at Stanford and Cornell, and department chair at the University of Wisconsin. Ross, a prominent advocate of eugenics, explained in his book The Old World in the New that “in race advancement the North Italians differ from the rest of their fellow-countrymen.” As he put it, “in the veins” of those from “Piedmont, Lombardy, and Venetia runs much Northern blood—Celtic, Gothic, Lombard, and German,” while southerners possess “Greek, Saracen, and African blood.”

The educator Leonard Covello pointed out the prejudice of American academics toward southern Italians.

“Rarely is there so wide an ethnic gulf between the geographical extremes of a nation as there is between Milan and Palermo,” Niceforo continued. “The astonishing dearth of literacy and artistic production in the South ought to confound those optimists who, identifying ‘Italian’ with ‘Venetian’ and ‘Tuscan,’ anticipate that the Italian infusion will one day make the American stock bloom with poets and painters. The figures of Niceforo show that the provinces that contribute most to our immigration have been utterly sterile as creators of beauty [original italics] . . . I have yet to meet an observer who does not rate the North Italian among us as more intelligent, reliable, and progressive than the South Italian. We know from statistics that he is less turbulent, less criminal, less transient.”

The sociologist’s racial and genetic assumptions came into fuller view under a section titled “Lack of Mental Ability.” Ross wrote that “steerage passengers from a Naples boat show a distressing frequency of low foreheads, open mouths, weak chins, poor features, skew faces, small or knobby crania, and backless heads. Such people lack the power to take rational care of themselves.” His jaw-dropping description, drawing on the concept of phrenology popular at the time, leaves the modern reader to wonder both what is a “backless head” and what was the shape of the heads choosing university faculty in the early 1900s.

Americans were also growing angry at the Italians’ high rate of repatriation, a response not unlike the reaction to Latinos today who send “good” American dollars back to their homelands. A cultural tension arose between wanting the immigrants out—a group of Harvard sociologists tried to pass an illiteracy act closing the doors to any immigrant who couldn’t read or write—and wanting them to become American as quickly as possible by adopting the “better” values of Anglo-Saxon culture.

One factor that Americans failed to fully consider, amid their prejudices and eating tips, was how ill prepared the southern Italian arrived for life in the United States. Southern Italians came from an agrarian economy not as traditional farmers but as contadini, landless peasants, who used primitive tools working arid land. They had not the slightest idea of how to farm according to American standards. They also settled mainly in urban areas, taking on brute industrial work for which they had no previous skills, and separating them from a rural way of life that had shaped their attitudes and ideas.

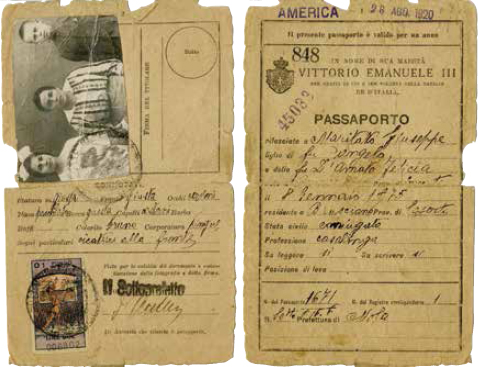

Passport that enabled the immigration of a casalinga (“housewife”) with two of her children in 1920.

They came from a land that needed every family member, including children, to help with work, which meant their rates of illiteracy were astonishingly high, indeed higher than elsewhere in Europe. In 1901, the rate among Italian men (women were almost always illiterate) in Campania was 70 percent, in Apulia 69.5 percent, in Basilicata 75.4 percent, in Calabria 78.7 percent, and in Sicily 70.9 percent. Covello speculated that the rates were actually much higher than these numbers suggest because Italian census takers rarely ventured to the inaccessible mountain towns where most of the contadini lived. (Even in the mid-twentieth century, one-quarter of the southern population remained illiterate.)

Many second-generation children felt the tug-of-war between American civic values and the duty of family loyalty.

After coming to America, the immigrants were equally mistrustful of schools. Compulsory education had been introduced in southern Italy as part of the Risorgimento reforms, and these laws had somewhat bolstered the level of literacy early in the new century (in the late nineteenth century, the illiteracy rate hovered between 88 and 98 percent in the southern regions). Many peasants, however, deprived of the opportunities linked to education, resisted the reforms and refused to send their children to school, believing it not only useless but a disruption to the patterns of family.

Families who emigrated in part to escape such meddling by outsiders received another bitter pill when they discovered the compulsory education laws in America. For the immigrants who arrived at the end of the nineteenth century, children could receive their working papers by age twelve. But by 1903, the law had extended compulsory education from the age of twelve to first fourteen and then sixteen—decisions that, in the words of one immigrant, “ruined all our hopes of a decent living, kept us poor, and destroyed the sanctity of the home.”

Italian immigrants often believed girls were better off at home helping their mothers than in school.

American schools, in the eyes of the Old World peasants, didn’t provide a “moral” education. The schools might teach patriotism, citizenship, and civic values, but that didn’t constitute the immigrants’ definition of morality, which was to respect your parents, help support them, and take care of them when they were old.

This delicate embroidery reflects the skills of Italian-American women, many of whom did piecework for garment manufacturers at home.

Now the “American ideas” were “going to their heads,” forever corrupting the young. It was bad enough that the boys had to go to school until sixteen, but the girls! What was the purpose of sending a girl to school, to mingle with strangers of both sexes, when she was supposed to help her mother at home? The Old World structure began to dissolve further, stirring increased resentment between parents and children, because women now had to leave home for work—an anathema in southern Italian culture—in order to support the family. The immigrants were perplexed as to why parents had to do backbreaking work while the children were being “idle” in school. They had been raised with maxims like this one from Basilicata: Fesso chi fa i figli meglio di lui (“Stupid and contemptible is he who makes his children better than himself”).

To the parents, school was la scuola, merely a noun, not a place in which to be actively engaged. It was uncommon for parents to know the names of the teachers—to them, faceless beings indoctrinating their children with ideas alien to their culture. Many parents simply ignored the compulsory education law, lying to truant officers by hiding their children or sending them to relatives. Working mothers would sometimes insist that their daughters had to miss at least one school day a week to keep up with the many household chores. Neighbors were also complicit in keeping children out of school, pretending not to know the names of anyone in the building if a truant officer knocked on their door.

The mistrust and anger toward the school system produced some of the lowest high school graduation rates in New York City. In 1931 a study found that only 11 percent of Italian-American students graduated high school (compared to an “American” graduate rate of 42 percent). These early attitudes would haunt Italian Americans for decades, retarding the assimilation process and creating a lasting stereotype of the ethnic group as one that didn’t value education. Teachers often pegged Italian Americans, especially boys, as troublemakers or students whose only academic worth was to pursue vocational careers.

Becoming American was a difficult feat for the second generation straddling two worlds. “We soon got the idea that ‘Italian’ meant something inferior, and a barrier was erected between children of Italian origin and their parents. This was the accepted process of Americanization,” Covello reflected in his memoir The Heart Is the Teacher. “We were becoming Americans by learning how to be ashamed of our parents.” While the first generation could choose to retreat into their isolated Little Italies, living among paesani and never learning English, their offspring confronted daily the challenges of mastering a new language and weighing the values inculcated in the classroom against those taught at home.

Italian schoolchildren ate crusty bread, like the loaves sold at this Mulberry Street bakery, distinguishing their lunches from their classmates’ “American” food.

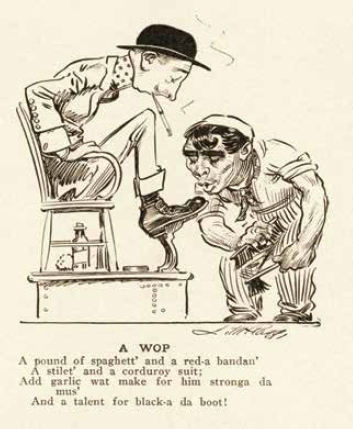

Becoming American meant rejecting one of the two worlds. It meant trying to hide the grease stains saturating the paper in which your school lunch of a fried potato and egg sandwich on crusty bread was wrapped, while the rest of your classmates ate ham on white bread with mayonnaise. Becoming American might mean dumping this sandwich in the garbage if you were too embarrassed to actually eat it in school—the act itself a blasphemy against the golden Italian rule of never throwing away good food. Becoming American meant speaking the dialect of your southern Italian region only at home, or listening to your parents but answering in English because that was your official language. Becoming American meant hearing slurs that now defined you and your people: dago, wop, guinea, spaghetti bender. And it also meant hearing your own parents and relatives reproachfully refer to you as the “Americano.” At the heart of being a second-generation American meant feeling the shame of your heritage and the sting of family betrayal, creating an inner turmoil from which one never fully escaped.

As a child, Rodolfo Guglielmi wanted to escape the boredom of his village in the province of Apulia. With a little luck, a magnetic stare, and a great pair of dancing legs, the restless boy from the village of Castellaneta would transform himself into Rudolph Valentino, Latin lover. Throughout his short life, Valentino faced both anti-Italian sentiment and the wrath of men who couldn’t believe that a swarthy southern European could steal the hearts of America’s wives and mothers.

Rodolfo’s family was a little better off than the rest of his village because his father, along with being a farmer, served as the local veterinarian. But a few years after his father’s death, Rodolfo, like most immigrants, crossed the ocean in a ship’s steerage.

After reaching New York and settling with relatives in Brooklyn, in 1913, he found a job as a landscaper on a Long Island estate. Always dreaming big, Rodolfo Guglielmi, like Jay Gatsby with rolling vowels, began to studiously imitate the mannerisms of the rich. The lessons were short-lived because he was quickly fired. He then supported himself through odd jobs like waiting tables, and he spent his free time in nightclubs, perfecting his tango and attracting the swoons of women wanting to be his partner. Beginning to make decent money dancing in cabarets and traveling for vaudeville tours, Rodolfo headed to Hollywood and changed his name to Rudolph Valentino.

His big career break came the next year when the influential screenwriter June Mathis insisted that he be cast as the lead in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and the movie became a huge box office hit. There were few roles for Italians in Hollywood at the time other than villains and peasants, but Valentino carved a new niche as the romantic lead from faraway places. Soon he was living the life he dreamed of—with all the accoutrements of wealth, including limousines, paisley smoking jackets, and fawning beautiful women. When he was cast as an Arab prince in The Sheik, the frenzy—hysterical women begged for autographs and grabbed at his garments—was unlike any ever seen in America.

Valentino became a fantasy figure, who attracted millions of mature women, married with children, not the teenyboppers of later decades screaming first for crooners and then for rock stars. His presence on the big screen gave women in puritanical America permission to indulge sexual fantasies of the Mediterranean lover. His profile was even emblazoned on packages of “Sheik” condoms released in 1931.

But the backlash was almost as powerful as the craze. Valentino’s second wife (people believed the marriage to his first dance partner had never been consummated) was badly managing his career, choosing roles that made him look more and more effeminate. His preference for European styles and silks only made matters worse. Men so detested Valentino and his pomaded, slicked-back hair—nicknamed the “Vaseline-o”—that the Chicago Tribune wrote an editorial called “Pink Powder Puff” blasting his mannerisms. “When will we be rid of all these effeminate youths,” read the editorial, “pomaded, powdered, bejeweled and bedizened, in the image of Rudy—that painted pansy?” As early-twentieth-century Americans were articulating or subconsciously registering their contempt for dark southern Europeans arriving en masse, Valentino’s stratospheric rise, fame, and riches made him a magnet for this vitriol.

Shortly after the Tribune incident, Valentino collapsed in a New York hotel room from an acute gastric ulcer. The world watched as his health deteriorated, and several days later he died from a severe infection at the age of thirty-one. Nearly seventy-five thousand people waited for hours outside the funeral home to see the star in a casket covered in gold cloth. Women swayed, screamed, and fainted. Across the country, fans waited for the arrival of the funeral train, kneeling in prayer when it passed.

FROM JOHN FANTE’S “THE ODYSSEY OF A WOP”

John Fante was born in Denver, Colorado, on April 8, 1909. He was the son of a bricklayer who had emigrated to the West from the region of Abruzzi in southern Italy. Fante created a deeply personal and confessional fiction about his first-generation parents, describing the conflict between trying to assimilate and retaining the values of their southern Italian village. In 1933, Fante’s short story “The Odyssey of a Wop” was published in the American Mercury, edited by his mentor, H. L. Mencken.

During a ball game on the school grounds, a boy who plays on the opposing team begins to ridicule my playing. It is the ninth inning, and I ignore his taunts. We are losing the game, but if I can knock out a hit our chances of winning are pretty strong. I am determined to come through, and I face the pitcher confidently. The tormentor sees me at the plate.

“Ho! Ho!” he shouts. “Look who’s up! The Wop’s up. Let’s get rid of the Wop!”

This is the first time anyone at school has ever flung the word at me, and I am so angry that I strike out foolishly. We fight after the game, this boy and I, and I make him take it back.

Now school days become fighting days. Nearly every afternoon at 3:15 a crowd gathers to watch me make some guy take it back. This is fun; I am getting somewhere now, so come on, you guys, I dare you to call me a Wop! When at length there are no more boys who challenge me, insults come to me by hearsay, and I seek out the culprits. I strut down the corridors . . .

I am nervous when I bring friends to my house; the place looks so Italian. Here hangs a picture of Victor Emmanuel, and over there is one of the cathedral of Milan, and next to it one of St. Peter’s, and on the buffet stands a wine pitcher of medieval design; it’s forever brimming, forever red and brilliant with wine. These things are heirlooms belonging to my father, and no matter who may come to our house, he likes to stand under them and brag.

So I begin to shout to him. I tell him to cut out being a Wop and be an American once in a while. Immediately he gets his razor strop and whales hell out of me, clouting me from room to room and finally out the back door. I go into the woodshed and pull down my pants and stretch my neck to examine the blue slices across my rump. A Wop, that’s what my father is! Nowhere is there an American father who beats his son this way. Well, he’s not going to get away with it; some day I’ll get even with him.

I begin to think that my grandmother is hopelessly a Wop. She’s a small, stocky peasant who walks with her wrists crisscrossed over her belly, a simple old lady fond of boys. She comes into the room and tries to talk to my friends. She speaks English with a bad accent, her vowels rolling out like hoops. When, in her simple way, she confronts a friend of mine and says, her old eyes smiling: “You lika go the Seester scola?” my heart roars. Mannaggia! I’m disgraced; now they all know that I’m an Italian.