Italian workers led the Lawrence millworkers’ strike after their wages were cut by thirty-two cents a week, the cost of four loaves of bread.

Italian workers led the Lawrence millworkers’ strike after their wages were cut by thirty-two cents a week, the cost of four loaves of bread.

The America of 1912, plump with excess and inequalities created by the Gilded Age, was a society in which the richest 1 percent controlled half of the nation’s wealth—an even heftier proportion than today’s 1 percent, who hold roughly a 35 percent share. With the wheels of industrialization spinning faster each year, and few laws to protect them, workers were expected to toil for whatever pittance a boss saw fit to offer.

Lawrence, Massachusetts, housed the nation’s biggest textile mills, employing about twenty-eight thousand workers. The average wage varied slightly among the myriad ethnic groups working in Lawrence, with southern Italians earning on the lower end, about $6.50 a week. Among all of the textile mills, the American Woolen Company was the behemoth—a six-floor building comprising thirty acres that extended for a quarter of a mile along the Merrimack River.

The company’s owner, William Madison Wood, bought an island for himself off of Martha’s Vineyard, along with yachts, servants, and a vast collection of cars. Wood, whose changed name belies his ancestry as the son of Portuguese immigrants, seemed to believe that the luckiest few who make it need not look back. Had he just craned his neck, he would have seen that the vast majority of workers lived in housing so cramped, dilapidated, and disease ridden that the term “huddle fever” coined to describe the anxiety these conditions produced was quite apt.

The Italians who settled in Lawrence felt fooled, betrayed, and for a usually cynical people, hopelessly naïve. How could they have believed the posters the American Woolen Company had put up throughout villages and towns in southern Italy about this New England town? One poster declared, “No one goes hungry in Lawrence. Here all can work, all can eat”; it pictured a ten-member family marching into a mill, the father hugging a bag of gold. Once in Lawrence, they could barely afford to feed their families, many surviving on bread and molasses. Before they decided to take action, conditions were so bad that a typical millworker could expect to live only to the age of thirty-nine.

The spark that would lead to the conflagration—and to one of the most significant strikes in American labor history—was caused, ironically, by a progressive action. The Massachusetts legislature, recognizing the workers’ untenable conditions, passed a law that reduced the workweek from fifty-six to fifty-four hours. They had passed similar legislation a few years earlier, and the mill owners had accepted its consequences; but this time, in January 1912, when the new law was to take effect, the owners refused to lose any more money and responded in marketplace fashion, cutting the workers’ pay by two hours, or thirty-two cents, a week.

For the workers, any cut in pay would be catastrophic. Although they crowded into some of the most dilapidated housing stock in the nation, developers scooped up the land and rented it for high prices, charging around three dollars a week for a cold-water flat. With these meager wages it was nearly impossible to save any money and feed and clothe their families. The cut would cost them four loaves of bread. Rumors swirled for months, but once the actual deduction appeared in their checks, a group of workers entered the mills shouting, “Short pay! All out!” This call began a walkout that would last over two months and fundamentally change the way many first-generation Italians in Lawrence saw their place in American society.

In earlier strikes, Italians, the lowest on the rung and in desperate need of work, had crossed picket lines as scabs. But this time Italians led the strike, acting from a nascent understanding that they were fighting for economic and social justice. One mill worker, a twenty-eight-year-old Italian immigrant named Angelo Rocco who had come to America in 1902, recognized that twenty-eight thousand strikers, who collectively spoke over forty-five languages, needed a strong union to keep them united after their first spontaneous walkout.

Rocco sent a telegram to the offices of the Industrial Workers of the World, the union that was nicknamed the “Wobblies” and was known for its radicalism. The IWW had formed in response to the American Federation of Labor, which at the time represented only skilled workers, not immigrant laborers. An IWW organizer and second-generation Italian American named Joseph Ettor saw Rocco’s entreaty and, after discussing the situation with his colleagues, boarded a train to Lawrence. He would also recruit a fellow paesano to Lawrence, his friend Arturo Giovannitti, a poet and editor of a Socialist weekly newspaper called Il Proletario.

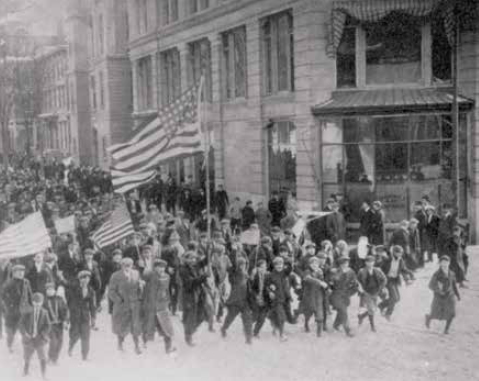

In the following days, the mood of the strike reflected the river’s ebb and flow: the heightened joy of morning solidarity often was depleted by the terror of chance events later in the afternoon. The mayor organized a state militia (which included student volunteers from Harvard, who were given credit on their midterm exams if they helped), armed with guns and bayonets to block access to the mills and canals. The strikers responded to the blockade by marching in a moving picket line, gathering by the thousands in the town’s center and singing and chanting in English, as well as their native languages of Italian, French, Polish, Russian, Portuguese, Greek, and German. The Italians waved the flags of the United States and Italy, declaring their heritage while acknowledging they were now American and would fight for the rights promised in this new land.

But as the weeks drew on, the workers’ jubilant voices thinned as violent clashes between the strikers and militia intensified. Having no clear sight of an endgame, the strikers were in danger of losing their stamina and resolve. Angelo Rocco’s hunch had been right: the organizers of the IWW provided the glue holding together this motley coalition of millworkers.

Unified, the striking millworkers sang and chanted in their many native languages.

Ettor, known as “Smiling Joe,” was a charismatic organizer and skilled orator who beseeched the strikers not to separate by ethnicity but to work collectively, and who enforced a strict policy of no violence, telling workers to always keep “their hands in their pockets” to escape any accusations. Ettor was fluent in several languages, which helped his ability to communicate with the workers, but it was his friend Arturo Giovannitti who proved the greatest inspiration to the crowd.

Arturo Giovannitti had come to the New World not to escape poverty, but to find a more just society than the monarchy he had left behind in Italy. He was the son of a pharmacist from the town of Ripabottoni in Molise and had received a classical high school education there. Both of his parents were inspired by the Republican values of Mazzini and encouraged their son to board a ship to Canada to study theology at McGill University. After graduating, Giovannitti had come to the United States, first working as an assistant pastor in a mining village in Pennsylvania.

Giovannitti’s theological training, which later evolved into an agnostic socialism, served him well in Lawrence. Just a few days after his arrival, he mesmerized a large crowd gathered at the Lawrence Commons with his “Sermon on the Commons,” a peroration that echoed the language of the Gospel’s Sermon on the Mount and applied its principles of social justice to the millworkers’ struggle.

“Blessed are the strong in freedom’s spirit,” Giovannitti exhorted, “for theirs is the kingdom of the earth. Blessed are the rebels: for they shall reconquer the earth. Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after equality: for they shall eat the fruit of their labor. Blessed are the strong: for they shall not taste the bitterness of pity. Blessed are the sincere in heart: for they shall see the truth. And blessed are they that do battle against wrong: for they shall be called the children of Liberty.”

Giovannitti’s words captivated the workers, crystallizing their inchoate feelings into a rallying cry for justice and a belief that victory was in reach. Yet the exuberance of that day would be short lived. On January 29, 1912, seventeen days after the strike began and several days after the Sermon on the Commons, someone fired a shot during a mass demonstration. Police blamed the strikers; the strikers blamed the police. Whoever fired, the untraceable bullet struck and killed a thirty-three-year-old millworker named Anna LoPizzo.

Although the police acknowledged that Ettor and Giovannitti were miles from the demonstration, they nevertheless arrested them, along with a millworker and strike leader named Joseph Caruso, and charged all three with murder by “inciting and provoking the violence,” which would lead to the death penalty if they were convicted. (The prior year, a fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City had killed 146 workers. The management’s standard practice of locking the factory doors to stop workers from taking breaks proved catastrophic. Yet the owners were charged merely with manslaughter, of which they were acquitted; they had only to pay a fine.)

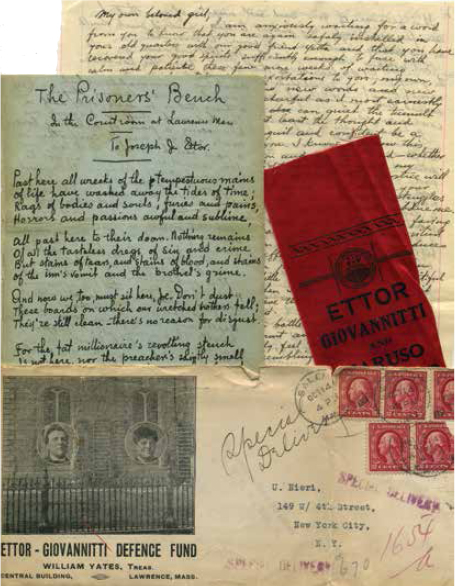

The police arrested union organizers Arturo Giovannitti and Joseph Ettor for a murder committed at a demonstration miles from where they were that day.

By putting the men in jail without bail, the mayor and prosecutors conveniently removed Ettor and Giovannitti from the streets and organizing halls. The IWW filled this void by sending their noted leader “Big” Bill Haywood to Lawrence. His commanding presence, and the attention created from the leaders’ arrests, brought national reporters to the scene. Haywood proved to be equally skilled, but he also had trepidation about the uphill battle the union faced with its resolute position that only a 15 percent wage increase would settle the strike. With no clear end in sight, they needed, in today’s parlance, a game changer, and a few Italian labor activists whom Haywood encountered in New York City’s Union Square gave him one.

The activists told Haywood that in some Italian towns, strikers employed a strategy of sending their children to families in other cities to keep them out of danger and to free up workers to meet the rigorous demands of conducting a strike. Haywood liked the idea and the attention it would receive, but he recognized the tremendous potential for something to go wrong if children were involved.

Still, he decided the risk was worth taking, and the IWW carefully mapped out a strategy to initially send over one hundred children from Lawrence to New York City. They placed ads in Socialist newspapers to help find and screen potential host families and recruited activists like the nurse and later founder of Planned Parenthood Margaret Sanger to help with the first children’s “exodus.” The children, registered by name, address, age, and nationality on a paper pinned to them and a duplicate kept by a secretary, were to be sent on a train to Grand Central Station. Chaperones would keep an eye on the children during the train ride and make sure that they met their host families at the station.

As anyone who has been raised by a traditional Italian mother knows, in normal circumstances she would more easily lie down on a train track than give her child to a complete stranger, even temporarily—but these were far from normal times. The strikers also feared keeping their children in Lawrence. Shortly after a bullet struck Anna LoPizzo, an eighteen-year-old Syrian boy died; he had taunted soldiers by throwing ice at them, and they responded by throwing bayonets at him. Sending children to New York City to stay with screened families seemed the lesser of two evils.

The striking workers employed a tactic used in towns in Italy: they sent their children to families in other cities.

And the children, donning white ribbons to stand out, were thrilled. They sang “The International” in Italian and French at the train station in Lawrence. Cheering families met them at Grand Central and placed their own coats on the children wearing threadbare garments. (Wealthy suffragettes who took up the Lawrence cause gained national attention by pointing out that the workers who made clothes for the world couldn’t afford to clothe their own children.) The evening of their arrival, the children were treated to a huge dinner prepared by the Hotel and Restaurant Workers union, topped off with ice cream, cake, and fruit. The children remained well fed for the duration of their stay, for many the first time in their lives, and the host families enrolled them in local schools.

The reaction in Lawrence, led by the mayor, was one of outrage. Lawrence could take care of its own children, he insisted, and many residents fumed that the strikers had unfairly slandered the town’s reputation. When the strikers attempted two weeks later to send another group of children to Philadelphia, Lawrence police tried to block them, dragging and clubbing some of the mothers. The melee, reported in national newspapers, caught the attention of President Taft, who ordered his attorney general to investigate.

Haywood’s instinct had been right; sending the children away changed the course of, and public sentiment toward, the strike. Congress decided to hold hearings, and the testimony they heard awoke a nation to the horrors taking place in the mills. Children described how they had to quit school at fourteen and work frenetically all day to keep pace with the machines, their labors earning them five dollars a week. They were asked if they had ever been injured on the job—a frequent occurrence—but one girl’s story captivated the hearing room. Camella Teoli was only thirteen, pulled out of school by a man who came to her parents’ house to recruit her. For the sum of four dollars, her father had given the man permission to forge her papers to say she was fourteen, the legal work age. Two weeks after she started, she had made the grave mistake of letting her pinned hair down, and the mill machines had scooped up the strands and torn off her scalp.

The strikers’ children marched in New York City, infuriating Lawrence officials.

Congress asked more questions: Why was a boy throwing ice attacked with bayonets? Why could families afford only bread and molasses? Why had the looms been accelerated? The congressional hearings were a public relations fiasco for the mill owners, and they knew it. They responded by offering the wage increase the union was demanding—amounting to roughly 15 percent, with a sliding scale that gave lower-paid workers the most—and ending the strike. Not only did the Lawrence strike increase these workers’ wages, but mill owners in neighboring New England towns, fearful that they would be targeted next, offered the same deal for an additional 250,000 workers. It was an extraordinary victory; the people of Lawrence rejoiced and the 240 children who had been sent away came home.

When the children testified in Washington about conditions in the mills, the owners knew sympathy had shifted to the strikers.

But although the strike ended in March, the summer arrived with Ettor and Giovannitti still in jail awaiting trial. By fall, they were brought into the courtroom, placed in a cage for all to peer into throughout the two-month trial. The prosecutors acknowledged that the men had been nowhere near the shooting, but they hoped to win the case by using the legal precedent set in the Haymarket Square trial. The accused in that case had been put to death not for planting bombs that killed six policemen in Chicago’s Haymarket Square in 1886, but for writing in anarchist journals.

The fate of the men in Lawrence would depend in part on how the jurors viewed the aims and actions of the strikers and the response of the militia. Who were the instigators of violence, and who were its victims? The trial was receiving worldwide attention, with support pouring in from trade unionists for the three men. After the defense and prosecution rested, Ettor and Giovannitti took the unusual step of asking to address the jury. Giovannitti had spent his time in jail reading the Romantic poets, Shakespeare, and Kant, and writing poetry. The courtroom was unprepared for this pale, fragile Italian who spellbound them with his eloquence.

“I, the man from southern Italy, have not told [Americans] how they should run their business,” said Giovannitti in the vertiginous position of stepping out of a cage to defend his life from the electric chair. “I am not here now to tell you what the future of this country should be. I know this, though, that I come from a land which has been under the rod of oppression for thousands of years, oppressed by the autocracy of old, oppressed during the Middle Ages by all the nations of Europe, by all the vandals that passed through it. And now Italy is oppressed, I may say, even by the present authority, as I am not a believer in kingship and monarchy . . . When I came to this country it was because I thought that really I was coming to a better and a freer land than my own.”

The courtroom remained hushed. Giovannitti turned to the prosecutor to remind him of the trial’s location in Salem, Massachusetts. “I ask the District Attorney, who speaks about the New England tradition, what he means by that—if he means the New England traditions of this same town where they used to burn witches at the stake, or if he means the New England traditions of those men who refused to be any longer under the iron heel of the British aristocracy and dumped tea into the Boston Harbor and fired the first musket that was announcing to the world for the first time that a new era had been established—that from then on no more kingcraft, no more monarchy, no more kingship would be allowed, but a new people, a new theory, a new principle, a new brotherhood would arise out of the ruin and the wreckage of the past.”

Giovannitti implored the jury to acquit Joseph Caruso, the one who could not speak English and defend himself, saying that Ettor and he himself bore responsibility—the former as the strike’s leader, and the latter as “aider and abettor.” And Giovannitti courageously announced that if acquitted, he and Ettor would continue to participate and help in any future strike to better conditions of workers’ lives, “regardless of any fear and of any threat.”

Even some veteran reporters shed tears as they listened; no one spoke after Giovannitti returned to his cage, and the trial concluded. By evening the jury announced that it had reached a decision, and the next morning the jurors acquitted all three men.

The spontaneous uprising in Lawrence united strikers in the sentiment that they were not machines born to work and die.

The Lawrence strike was a turning point for Italian Americans. For the first time they had trusted themselves to challenge authority. They had not retreated in silence and suspicion. And two formidable Italian Americans, Ettor and Giovannitti, organizer and poet, had represented them and their fellow millworkers with heroism and lyricism.

The events in Lawrence would later be known as the “Bread and Roses” strike, from the James Oppenheim poem of the same name. “Hearts starve as well as bodies,” read the poem, and workers needed not only bread but roses, too. The poem was published a month before the strike but later cited to express the sentiment found among the millworkers. The spontaneous uprising in Lawrence improved workers’ wages but also united them in their declaration that men and women were not machines born to work and die. They needed nourishment beyond a weekly paycheck—a feat hard to achieve if bosses pressed them so hard that only sleep could mitigate the pain. The months of singing, chanting, and believing in a cause greater than any single individual gave the workers a purpose and infused their days with dignity. For a brief moment in history they could believe, as Giovannitti exhorted in his courtroom speech, “that a new brotherhood would arise out of the ruin and the wreckage of the past.”

PERSONAL CORRESPONDENCE OF ARTURO GIOVANNITTI

Some of the collected correspondence of Arturo Giovannitti when he was in jail awaiting trial.