After the anarchist bombings, the government raided the headquarters of the IWW in New York.

The mystical faith of Italian Americans, passionately expressed in an outreach to saints and outpouring into the streets, offered solace and guidance to millions finding their way in a newly adopted country. In the early twentieth century, however, a small group of Italian Americans practiced a secular idea with a fervor normally associated with religious devotion. This group venerated the philosophy of anarchism.

While anarchism took root in other European countries, particularly Russia, France, and Germany, in Italy the movement was abetted by a deep-seated suspicion of the government, military, and church, all of which were believed to have turned a blind eye throughout history to the desperate plight of the people. The anarchist movement was a means, its devotees believed, to restore human dignity stripped away by conquerors, monarchs, and corrupt clergy.

Anarchism established sturdier roots among Italians in America than it did in Italy, where socialist thinking was more popular. In the New World, the immigrants arrived with dreams of a just and fair American system to replace the broken one they had left behind. As those dreams turned to ash in the furnace of a newly industrialized America, the radical anarchist ideology took hold.

The anarchists held a Utopian belief that a world without rules and laws would bring out the best, not the worst, in human nature. Opposite to the Hobbesian notion that a central government was necessary to combat the “nasty, brutish, and short” life of man, the Italian anarchist leader Luigi Galleani believed that a world without government would be one of cooperation, collectivism, and liberty. By eliminating laws, private property, and the profit motive, men and women could act as creative individuals and live fulfilling and ethical lives without the constrictions of church or state.

La Cronaca Sovversiva (“Subversive Chronicle”) was the anarchist newspaper of Luigi Galleani, who wanted to abolish all civic and religious institutions. Sacco and Vanzetti developed their views about anarchism from this publication.

Anarchist circles also provided a sense of community for isolated immigrants overwhelmed by the harsh demands of daily life. They gathered for picnics and weekly meetings, formed theatrical groups, and put on plays to express their ideas and imagine a life beyond the grinding workplace conditions they faced. They clung tenaciously to this “ism,” the most radical challenge to capitalism, proclaiming that human beings were not machines and that the system perpetuating their mistreatment had to be abolished.

Two men, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, would come to represent the idea of Italian anarchism in this country, and ultimately would be put to death for a crime they vehemently denied committing. Throughout the twentieth century, their dolorous faces, like a Rorschach test, would be sanctified or vilified, their piercing stares reflecting the plea of martyrs or the sneer of militants, the interpretation dependent on one’s political leanings and worldview.

An anarchist movement developed in the United States in the early 1900s with the intent of improving worker conditions.

Ironically, these men who, in America, had abandoned religion for atheism would be remembered as Christ-like figures sacrificed on the cross of a venal and corrupt judicial system. In one of Vanzetti’s prison letters, he described the seven excruciating years awaiting the promise of a new trial or the finality of death as his “ascension to the Golgotha.” He wrote, “It is good for them if they succeed to loosen me . . . crushed in flesh and in spirit—a shadow of a man, a human rag—and still better to them if they will turn me out well nailed amongst six cheap planks.”

Sacco and Vanzetti both emigrated to America in 1908. Sacco was from the village of Torremaggiore in southern Italy; Vanzetti, from the town of Villafalletto in the northern Piedmont region. While neither family was wealthy, both men had fared much better in Italy than the average peasant. From the beginning of their journey to America, these two men, who would be forever linked in history, possessed different dreams and dispositions. Sacco wanted to fulfill the desire of many Italian boys—to come to a new land of promise and opportunity—and after arriving in America, he soon married and had a child. Vanzetti was a loner who never married. He left Italy in deep grief over his mother, who had died in his arms from cancer. His father begged him to stay with the family and help care for his toddler siblings, but Vanzetti saw the ocean as perhaps the only vessel that could contain his vast grief.

Sacco’s father owned vineyards and olive orchards, and the son would bring his inherited passion for outdoor life and gardening to the New World, even taking note in his prison cell of “the beautiful cloves and the red black beauty vivid roses” friends brought. After working in a series of construction jobs, he decided to apprentice in a shoe factory and eventually mastered the skill, becoming an edge trimmer and earning the excellent salary, for an immigrant, of roughly eighty dollars a week.

While he did not share the economic plight of his fellow Italians, Sacco deeply sympathized with them and became angered by the exploitation he saw. Living near Boston, Sacco read about the Lawrence strike and the arrests of Ettor and Giovannitti, and he committed himself to helping the strikers and their cause. He wrote to his daughter, his second child, whom he would come to know only through prison bars, that “the nightmare of the lower classes saddened very badly your father’s soul.”

Bartolomeo Vanzetti had a much more difficult time adjusting to life in America. Lonely, miserable, and needing work, he was horrified by the poverty and deprivation that he witnessed in New York. He found a job as a dishwasher but struggled to live on the paltry sum of six dollars a week for seventy hours of labor. The tiny steaming spaces in which he worked irritated his lungs, already damaged by pleurisy. He traveled to other states, but life remained just as bleak, digging ditches and building railroads. He returned to New York to try to find work as a pastry chef, a trade he had practiced in Italy, but employment was sporadic, and for stretches of time he ended up homeless. Eventually, Vanzetti settled in Massachusetts and seemed most content working outdoors as a fish peddler.

A pamphlet published by Luigi Galleani’s radical Gruppo Autonomo urged the electorate not to vote.

Vanzetti was raised Roman Catholic, played priest in childhood games with his sister, and staunchly defended the religion in adolescence. But his mother’s illness and death began to destroy his faith, and as a teenager he abandoned it. Waiting in the New World for Vanzetti was the new belief system of anarchism, and he passionately embraced it. In his letters he described anarchism “as beauty as a woman for me, perhaps even more . . . Calm, serene, honest, natural, viril, muddy and celestial at once.”

Some anarchists, like Carlo Tresca, advocated working with labor unions to effect change, but Sacco and Vanzetti followed the most radical strain of the movement put forth by Luigi Galleani, who Vanzetti referred to as “our master.” Galleani, a prolific writer and mesmerizing speaker, believed that if the monarchies of Europe were inherently corrupt and capitalism devoured the possibilities of fair democracy in America, then all of these systems had to be abolished. According to intellectual historian Paul Avrich, the Galleanisti saw themselves as “slayers of tyrants, wreakers of vengeance, fighters for freedom.”

Galleani sought “the Ideal”—a world free of government, law, and property—but this Ideal would have to be achieved by violent insurrection. He published a manual called La salute è in voi! (“Health is in you!”), which detailed the ingredients and recipe for bomb making. Galleani believed that bombings and assassinations were justified because the victims were capitalists and government officials. Sacco and Vanzetti were not pacifists or naïfs, as many have portrayed them. They were faithful members of Galleani’s Gruppo Autonomo and planning a world that could match their anarchist dreams. The ethical ideas and whimsical musings portrayed in the hundreds of letters they wrote in prison contradict the affiliations and friendships they both kept with violent bombers, or perhaps reveal the darkest conflicts of the human soul.

As April drew to a close in 1919, thirty bombs were sent in packages labeled “Gimbel Brothers, New York” to capitalists, jurists, and political figures who had suppressed radical action and union strikes, including John D. Rockefeller, J. P. Morgan, William Madison Wood, and Oliver Wendell Holmes. Civil liberties had been severely restricted since the country’s 1917 entry into World War I. Even speaking against the war could land someone in prison, and radicals under assault were determined to strike back.

Stamped on each package wrapped in brown paper were the words “novelty” and “sample,” with the logo of an alpine mountain climber and the return address of the Gimbel Brothers’ department store. The cardboard box contained a glass bottle filled with powerful homemade explosives. Intricately constructed and requiring significant skills to assemble, the explosives suggested that the bomb makers possessed technical acumen but lacked sophistication: they naïvely assumed that a figure like John D. Rockefeller opened his own mail.

The first person gravely injured was a black maid who lost her hands opening the deadly container. The package had been sent to an ex-senator from Georgia who had cosponsored deportation legislation. A New York City postal worker reading about the crime on his subway ride home remembered seeing packages similarly addressed. He immediately returned to the post office and discovered sixteen boxes with Gimbel Brothers labels sitting undelivered because of “insufficient postage.” The anarchists’ scheme and dream—to have all the bombs explode on May Day—failed because someone neglected to lick enough stamps. (This wasn’t the first time the Galleanisti erred in attempting to carry out their revolutionary plots: In 1916, a follower tried to assassinate the new Roman Catholic cardinal of Chicago at a banquet honoring him by putting arsenic in the soup. The poisoned stock sickened the two hundred guests, but no one died. The anarchist chef, heavy-handed with the arsenic, had poured so much into the steaming pot that everyone merely vomited it up.)

By early June, the anarchists had regrouped and decided to carry out their mission personally. Across the street from where Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt lived in Washington, DC, in front of the home of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, a handsome, nattily dressed man held a suitcase containing a powerful bomb. Echoing the macabre slapstick of “insufficient postage” and arsenic-laced soup, the assailant either tripped or improperly timed the fuse. The bomb blew him to pieces, and its powerful force shattered Palmer’s windows and tossed people from their beds a few houses away. That same evening in other parts of the country—Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Boston, New York, and New Jersey—bombs went off, timed like tolling bells to create maximum chaos and confusion. The carefully picked destinations for the deadly devices included the rectory of a Catholic church and the homes of those who had suppressed radicals.

Anarchist followers of Luigi Galleani attempted to blow up the house of US Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer.

Flyers titled “Plain Words” that denounced capitalist abuses and declared future bloodshed and destruction blew in the wind at the scenes of the crimes. The literature eventually was traced to members of Luigi Galleani’s Gruppo Autonomo in Boston. The dead man outside Palmer’s house, Carlo Valdinoci, was a friend of Sacco and Vanzetti’s, and his sister came to live with the Saccos after her brother’s death. Another Gruppo Autonomo member and good friend of both men, Mario Buda, was tied to several of these bombings and believed responsible for the Wall Street explosions set off five days after the indictment of Sacco and Vanzetti—most likely in protest—that killed over thirty people and wounded hundreds. Buda is believed to have placed one hundred pounds of dynamite in a horse-drawn wagon along with five hundred pounds of cast-iron weights, detonating it across the street from J. P. Morgan bank and causing America’s greatest terrorist disaster of the time.

Throughout its history, the US government has never taken kindly to, or sat passively before, acts of terrorism. Anarchism was outlawed in 1901, after a Polish anarchist shot President William McKinley, and Attorney General Palmer responded to the 1919 incidents with a broad sweep known as “the Palmer raids,” in which he deported over four thousand people, many without due process, thought to be involved in radical activity. At the time, the country was also reeling from the Red Scare; the Bolsheviks had taken control in Russia, and people feared the revolution would spread to America.

It was under these circumstances that police arrested Sacco and Vanzetti for a robbery in South Braintree, Massachusetts, in 1920 with little credible evidence connecting the men, particularly Vanzetti, to the crime. Two men had been murdered in a payroll robbery, and a police chief decided that anarchists trying to finance their activities—not previously suspected local thugs—had committed the crime. The police chief linked a stolen car in a repair shop to the robbery and told the mechanic to inform him of anyone who came looking for it. When Sacco and Vanzetti arrived to claim the car of their friend, Mario Buda, the mechanic’s wife called the police, who eventually caught up with the men after they had boarded a trolley car.

At the time of their arrest, Sacco and Vanzetti were both armed, probably because of their growing fear that the feds were closing in on Gruppo Autonomo. One recently arrested member had jumped to his death from the window of a federal office building after breaking the anarchists’ code by revealing the names of coconspirators. Sacco and Vanzetti later said they had intended to gather and hide anarchist literature that evening (Upton Sinclair, who researched the case, argued that “literature” was merely a euphemism for explosives). After being arrested, and not knowing what crime they had been accused of, both men repeatedly lied when questioned about their evening activities. Their responses and evasions would be held against them during the course of the trial.

The presiding judge, Webster Thayer, declared that the conviction of both men would rest not on a positive identification—indeed there were far too many conflicting testimonies—but on a “consciousness of guilt” to the South Braintree crime, which the prosecution argued the men had displayed upon arrest. Yet Sacco and Vanzetti lied probably to avoid being linked to their anarchist circle and activities that evening, not, as the judge implied, to distance themselves from the payroll crime.

Or, as Sacco later told the journalist Mary Heaton Vorse, “If I was arrested because of ‘The Idea,’ I am glad to suffer. If I must I will die for it. But they have arrested me for gunman job.” The evidence against both men for this “gunman job” was so weak that it exposed the prejudices and limitations of the American judicial system and created a worldwide outrage over the men’s eventual executions.

Nicola Sacco (right) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (middle) would become the face of Italian anarchism in this country.

Judge Thayer decided to try Vanzetti for another payroll robbery, a botched and unsuccessful earlier incident in Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Despite conflicting testimony—bystanders thought the assailants were either Russian or Polish—Vanzetti’s dark, “foreign” countenance created enough suspicion for people to change their original identification. The attempted robbery took place on Christmas Eve, yet Vanzetti’s alibi—he had been selling the traditional fish that Italians devour that night—did not convince the jury, despite the testimony of sixteen witnesses who said they had bought eels from him. The jury determined that the Italians, who could barely speak English, were merely assembling a group alibi to protect one of their own. Even the governor of Massachusetts commented that the word of Italians couldn’t be believed. The Italians, on the other hand, were shocked that their words, no matter how unpolished, weren’t deemed credible. Once the jury declared a guilty verdict, the wheels were set into motion: the trial for the Braintree robbery was bound to produce the same verdict, despite a substantial lack of evidence against Vanzetti and a case against Sacco that left many doubts.

Their trial, which lasted six and a half weeks, called on a dizzying 167 witnesses. Many eyewitnesses could not identify either Sacco or Vanzetti. Vanzetti was accused of driving the getaway car, but the driver had been heard to speak perfect English, unlike Vanzetti’s heavily accented tongue. Witnesses supported Sacco’s alibi that he was at the Italian consulate that day obtaining a passport to return to Italy. A bullet traced to Sacco’s gun was said to have killed the payroll guard, but there was credible evidence that the bullet had been substituted during a test firing. While reasonable doubt existed, the jurors, charged to find a “consciousness of guilt,” quickly reached a guilty verdict.

Defense lawyer Fred Moore, a flamboyant labor attorney from California who had helped secure the release of Ettor and Giovannitti and never failed to make the staid Judge Thayer wince, requested a new trial. The subsequent odyssey for both men would last seven years. During this time, a hardened criminal named Celestino Madeiros confessed to the Braintree robberies while in jail. Although Madeiros wouldn’t name his gang, his description fit a group of thugs led by Joe Morelli, who were among the original suspects. Morelli’s mug shot bore a striking resemblance to Sacco’s profile, their Buick getaway car matched the vehicle the police sought, they possessed the type of guns used in the crime, and Madeiros had been found with nearly $3,000 in cash, while no money had ever been traced to Sacco and Vanzetti.

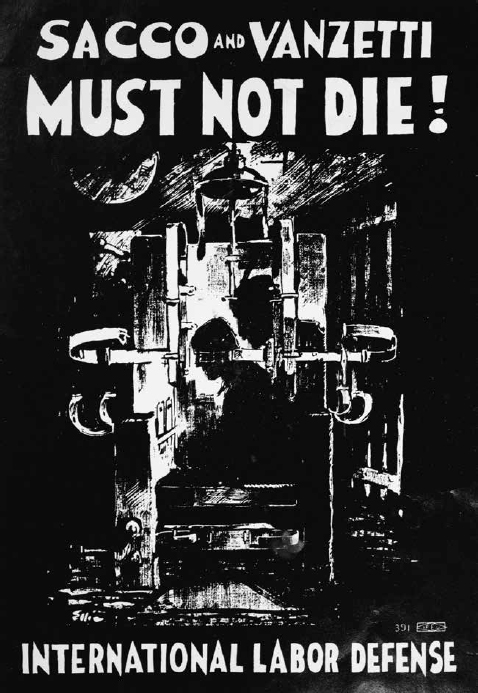

The Sacco and Vanzetti case received international attention as unions and activists around the country rallied to the two men’s defense.

The bias of Judge Thayer was also revealed: after denying Sacco and Vanzetti another trial, he was overheard at a Dartmouth football game (the judge’s alma mater) saying to a professor, “Did you see what I did with those anarchist bastards the other day? I guess that will hold them for a while! Let them go to the Supreme Court now and see what they can get out of them!”

The case’s many inconsistencies and the government’s determination to prosecute radicals without sufficient evidence prompted Felix Frankfurter, who would later become a Supreme Court judge, to write an article for Atlantic Monthly in 1926 that challenged the conduct of the trial and detailed its many weaknesses. Frankfurter later expanded his article into a book, which further enraged the clubby Boston establishment, furious that a Jewish outsider would suggest a tainted legal system in the commonwealth.

Despite the overwhelming amount of new material, the Massachusetts Supreme Court would not reverse Thayer’s denial of a new trial. Pleas were then taken to the governor of Massachusetts, Alvan T. Fuller, who appointed a three-man commission headed by the president of Harvard. But the bias against the men was too strong—despite a swelling support in the United States and worldwide rallies, protests, and strikes—to make any difference. Fuller’s commission ultimately upheld the conviction, and after seven excruciating years, all pleas were exhausted.

The denial of the right to a new trial sent supporters into despair because they believed that America’s judicial system had been badly, if not irreparably, tarnished. As Katherine Anne Porter explained in The Never-Ending Wrong, a reflection written fifty years after her participation in the protests, “It was a silent assembly of citizens—of anxious people come to bear witness and to protest against the terrible wrong to be committed, not only against two men about to die, but against all of us, against our common humanity and our shared will to avert what we believed to be not merely a failure in the use of the instrument of the law, an injustice committed through mere human weakness and misunderstanding, but a blindly arrogant, self-righteous determination not to be moved by any arguments, the obstinate assumption of the infallibility of a handful of men intoxicated with the vanity of power and gone mad with wounded self-importance.” Porter was among those who stood vigil the night of the execution, watching the light in the prison tower flicker shortly after midnight on August 23, 1927—the sign that powerful voltages of electricity had been charged through the bodies of Sacco and Vanzetti.

The passion surrounding the case only grew more intense as the men became worldwide martyrs. Cities feared reprisals, and police were sent to guard subways, railroads, and ship terminals. Hundreds of thousands of people poured into the streets for their funeral. Over the years, in addition to Porter, the painter Ben Shahn, writers John Dos Passos and Upton Sinclair, poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, and folk singer Woody Guthrie created works about them. A year after their execution, supporters published the Letters of Sacco and Vanzetti, and both Sacco’s tentative English prose, which had grown more graceful through years in prison, and Vanzetti’s often lyrical passages won more hearts. “The truth is that not only have I not committed the two crimes for which I was convicted, but I have not stole a cent nor spilt a drop of human’s blood—except my own blood in hard labor—in my whole existence,” wrote Vanzetti.

The truth about the information Sacco and Vanzetti possessed is shrouded in mystery. The majority of their supporters knew little about the depth of their anarchist activity; they were protesting the lack of evidence against the two men for the payroll robberies. Sacco and Vanzetti became a parable of justice denied: the judicial system will be merciless; no one will believe your innocence if you are swarthy, speak accented English, and are accused of a crime.

The actions of the American elite, the Dartmouth judge, the Harvard-led commission, and the prosecutors in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts reflected the warning President Woodrow Wilson had made a decade earlier: “Hyphenated Americans,” he said, “have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life.” The fanatical actions of militant anarchists, a tiny fraction of the millions of Italian Americans then residing in America, tainted the community and helped to fuel anti-Italian prejudice.

In 1924, three years before Sacco and Vanzetti’s death, Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act that put into place large-scale immigration quotas, drastically cutting the number of people who could emigrate from southern and eastern Europe. A key expert witness to the congressional panel and the man largely responsible for getting the legislation passed was Harry Laughlin, a eugenicist and vowed proponent of eugenic sterilization, who believed that the American stock had been polluted by “alien hereditary degeneracy.” Congressman Albert Johnson, who chaired the Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, was himself an honorary president of the Eugenics Research Association. The actions of Congress deepened the perception of “good” Americans and “untrustworthy,” biologically inferior foreigners who were now, to the lawmakers’ dismay, rapidly reproducing. President Calvin Coolidge concurred, explaining, “Biological laws tell us that certain divergent people will not mix or blend.”

After the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, the message to Italian Americans became clear: any dissent or difference will no longer be tolerated. Blending fully into American life, a difficult dance for southern European Catholics struggling to understand Anglo-Saxon culture, could be the only path ahead.

It was the end of a long day on March 25, 1911, when a fire broke out at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, trapping the workers who occupied the top three floors. The fire claimed the lives of 146 garment workers, mostly Italian and Jewish immigrant women. Bystanders on Greenwich Village streets noticed smoke and saw bundles falling from the top-floor windows. To their horror, they realized these were the bodies of young women, mostly between the ages of sixteen and twenty-three, leaping to their deaths. Many had been fighting the previous year for better working conditions during a citywide garment strike, but the Triangle owners refused to let them unionize.

The horror of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire became a galvanizing force for young immigrant women, whose sorrow turned to rage and then to a purposeful anger. One of those future leaders was Angela Bambace, who was thirteen at the time of the incident and by the age of eighteen had begun organizing garment workers.

Angela Bambace grew up in East Harlem, and like her mother, who trimmed hat plumes and worked in a shirtwaist factory, she became a seamstress. Both Angela and her sister Maria began to attend Italian socialist and anarchist meetings and decided to organize workers to improve factory conditions. Their mother, Giuseppina, supported her daughters but also feared for their safety, knowing that hired thugs often roughed up union advocates. Giuseppina accompanied her daughters to their union activity, always carrying a rolling pin to ensure that a protective motherly swing was in arm’s reach.

In 1919, when Angela was galvanizing women garment workers to go on strike, she also agreed to her father’s wish that she marry Romolo Camponeschi, a Roman-born immigrant who worked as a waiter. The mismatched pair—Romolo sought the normalcy of domestic life while Angela set out to improve the lives of the working class—grew further apart after Angela gave birth to two boys, Oscar and Philip. It was boring, she would later admit to her grandchildren, “to stay home and make gnocchi and take care of the kids.”

Angela Bambace and sons Philip (left) and Oscar.

The marriage ended a few years later, followed by a bitter custody battle. Because of her organizing activities and involvement in socialist and anarchist circles, the judge ruled Angela an unfit mother and awarded custody to the father. Luckily for the distraught Angela, her mother lived near Romolo and agreed to help raise the grandchildren, allowing Angela to see them.

Through the years, the boys had to endure their mother’s frequent absences and the many causes she supported. When Oscar celebrated his seventh birthday, he discovered the bad luck of being born on the date set for the midnight execution of Sacco and Vanzetti. His “party” consisted of a roomful of heartbroken adults gathered around the kitchen table, underneath which Oscar spent the evening.

After a long day’s work as a factory seamstress, Bambace took on the perilous activity of union organizing. She was thrown down a flight of stairs by an enraged employer and even landed in jail. In the 1930s the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) sent her to organize small factory shops in Maryland and Virginia. Never learning to drive, she was chauffeured to these southern towns by a union worker. The two formed a motley pair: an Italian-American woman who spoke like a longshoreman and an African-American driver who had only one eye. They often had to sleep in the car because hotels refused to accommodate a black man.

Angela Bambace became the first Italian-American woman elected into the male-dominated labor hierarchy, as vice president of the ILGWU. During the half century that Angela Bambace worked for the union, she recruited and organized thousands of workers, shaping the ILGWU into a powerful force. She dedicated her life to improving conditions for garment workers and helping to ensure that tragedies like the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the worst industrial accident in New York City’s history, would never take place again.