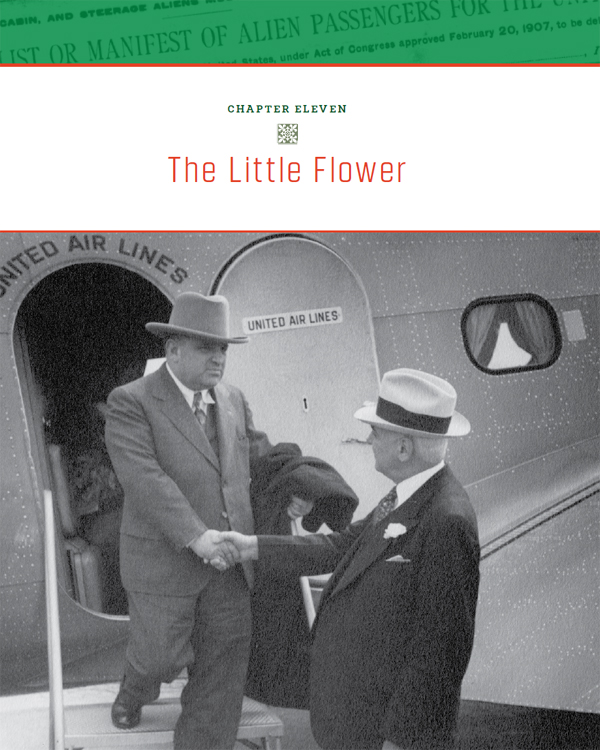

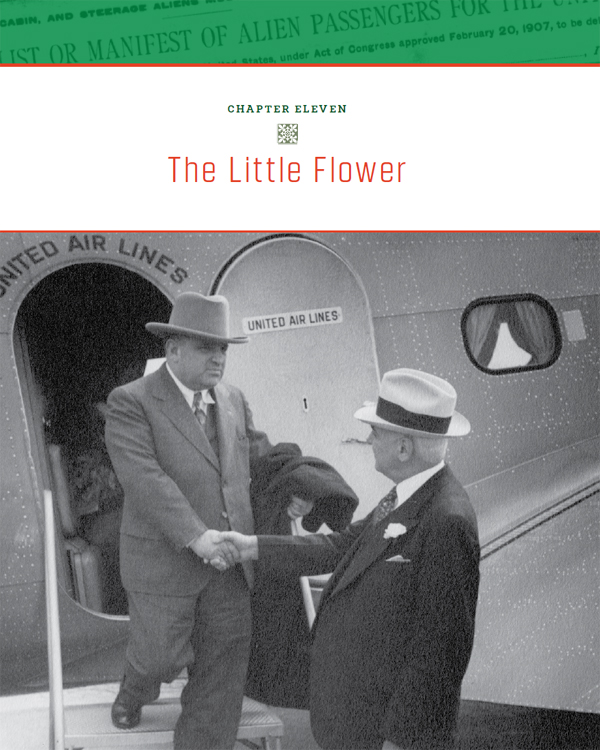

Fiorello La Guardia (left) wasn’t the first Italian-American mayor of a major city. Angelo J. Rossi, mayor of San Francisco (seen here with La Guardia), was. But as mayor of New York, La Guardia became the nation’s best-known political figure after Franklin Roosevelt.

When Fiorello La Guardia was sworn into office on January 1, 1934, as mayor of New York City, it was the first wet New Year’s Eve after fourteen interminably dry ones under Prohibition. The inauguration was particularly thrilling for Italian Americans, now numbering over one million in New York City and exuberant that one of their own had reached this pinnacle, ending the control of a corrupt band of Tammany Hall politicians that had drained the city’s coffers. La Guardia wasn’t the first Italian-American mayor of a major city—Angelo J. Rossi of San Francisco beat him by two years—but he was the first Italian American in Congress, and as mayor of New York he became the nation’s best-known political figure after President Franklin Roosevelt. For an ethnic group that had been the target of an increasingly virulent nativist prejudice during the previous decade, La Guardia’s election was monumental.

Fiorello La Guardia was, in many ways, the perfect representative for a beleaguered Italian people. The indefatigable politician, who reached just over five feet in height, had suffered his own share of indignities and personal tragedies. Unlike the anarchists intent on destroying a system that they believed caused only misery, La Guardia channeled his anger and grief into creating effective and lasting change through government action.

Born in a four-story building in Greenwich Village, Fiorello (which means “little flower”) spent most of his childhood in Arizona. His parents, Achille La Guardia (a musician born in the town of Foggia in southern Italy) and Irene Luzzatto-Coen came to America after Achille had been offered the opportunity to play and arrange music here. Although a talented cornetist, Achille never found permanent work with an orchestra and eventually joined the army as a bandmaster—a decision that took the family west.

Fiorello’s mother was a Sephardic Jew born in Trieste when the city was under Austrian rule. As part of a prominent Italian Jewish family, though, she always thought of herself as Italian. With Achille a lapsed Catholic and Irene not particularly religious, they raised their children as Episcopalians, adding to the mixed cultural and religious heritage that shaped La Guardia’s outsider status.

The family moved around to follow Achille’s military assignments, and while stationed in Florida during the Spanish-American War, he became ill eating rancid beef, which had been returned from England a year earlier, embalmed with preservatives, and sold to the army for its rations. Thousands of others similarly suffered food poisoning in what became known as the “embalmed” beef scandal, and Achille developed hepatitis, further complicated by malaria. The realization that disreputable contractors out to make a profit had sickened his father, along with thousands of other soldiers, made a profound and lasting impression on the adolescent Fiorello. His father retired from the army a weakened and angry man, and died several years later from a heart attack.

Before La Guardia’s father died, the family returned to Trieste to live with Fiorello’s maternal grandmother. Fiorello stayed for a few years to help support his mother, but eventually he became anxious to return to America, and he found employment in Ohio. The job didn’t last long. Fiorello longed to live in New York, and his knowledge of several languages secured him a job at Ellis Island working for immigration services as an interpreter and caseworker. La Guardia never finished high school or attended college, but he took courses to acquire a high school diploma and enrolled in night classes at New York University Law School, where he earned a degree. At Ellis Island, La Guardia witnessed the cruel treatment of immigrants and arbitrary permanent separations that took place after family members failed the medical inspection. These incidents stoked his rage. By the time La Guardia arrived in Washington, he was ready to fight for social justice.

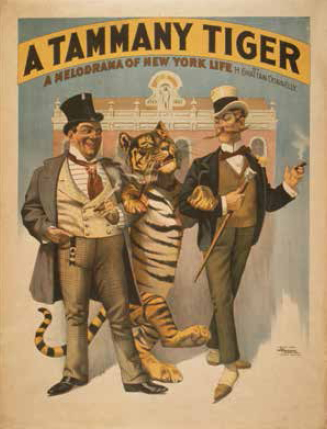

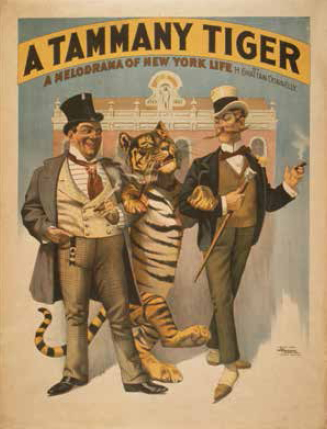

The political career of Fiorello La Guardia—which began with his first election to Congress in 1917—combined tenacity, improbability, and luck. He was a die-hard progressive, sympathetic to immigrants and labor, but he ran on the Republican line because the brazenly corrupt Irish political machine known as Tammany Hall dominated the Democratic ticket. The Republicans, composed mostly of New York’s gentry, considered La Guardia crude and loud. But they also needed the pugnacious and overwhelmingly popular politician because there was little Republican representation in the state.

La Guardia’s first bill in Congress—a surprising move for a freshman, who is supposed to be seen but not heard—sought penalties for anyone who knowingly sold inferior supplies to the army or navy: a prison term in times of peace and the death penalty during war. The bill never went any further than the Judiciary Committee, the usual fate of legislation for a junior congressman without strong party backing. But it became clear from the beginning of his career that La Guardia meant to be seen and heard.

La Guardia ran as a Republican because the brazenly corrupt Irish political machine known as Tammany Hall dominated the Democratic ticket.

La Guardia briefly left Congress to serve as a fighter pilot during World War I. Strongly patriotic at a time when his ideological colleagues remained pacifists, he enthusiastically applied to a training camp. The congressman had learned to fly several years earlier, when he served as the attorney for the airplane company of a man named Giuseppe Bellanca. La Guardia was sent to Italy as the lieutenant of a bombing squadron, and returned to the States a major. While some of his supporters denounced his decision to leave the people of his district to fight in the war, he won reelection, returned to Washington, and spent the remainder of his time there putting forth a progressive agenda that prefigured major themes and ideas of the New Deal.

An attractive Italian dress designer whom La Guardia had courted before the war, Thea Almerigotti, from his mother’s hometown of Trieste, finally agreed to marry him. The next year Thea gave birth to a baby girl, Fioretta. The sheer happiness of this time was extremely short-lived; both wife and daughter developed tuberculosis, a disease commonly acquired from living in tenements, as the couple did. Two years later, Fiorello’s daughter died of tuberculous meningitis, and his twenty-six-year-old wife, of pulmonary tuberculosis.

Within two years after La Guardia married Thea Almerigotti, both she and their baby girl, Fioretta, would die from diseases commonly acquired from tenement living.

When a newspaper reporter asked La Guardia shortly after his wife’s death how he would spend $1 million a day—the daily sum of New York City’s annual budget—La Guardia responded with the fury and passion that would define his tenure in Congress and as mayor. “First I would tear out about five square miles of filthy tenements, so that fewer would be infected with tuberculosis like that beautiful girl of mine, my wife, who died—and my baby . . . Then I would establish ‘lungs’ in crowded neighborhoods—a breathing park here, another there, based on the density of population . . . Milk stations next. One wherever needed, where pure, cheap milk can be bought for babies and mothers learn how to take care of them. After that the schools! I would keep every child in school, to the eighth grade at least, well-fed and in health. Then we could provide widows pensions and support enough schools for every child in New York on what we saved from reformatories and penal institutions . . . I would provide more music and beauty for the people, more parks and more light and air and all the things the framers of the Constitution meant.”

A significant and popular Progressive Party existed in America in the 1920s that vigorously challenged the status quo and culminated in the effort to elect Robert La Follette as president. La Guardia was a member of this movement, which he described as “the arousing of a united protest against conditions which have become intolerable”—conditions such as the high cost of food and rent, vast economic inequality, a tax system that significantly favored the rich, and the exploitation of workers.

Although the Progressive movement made fighting for economic equality a keystone of its agenda, most of its members came from the Midwest, which meant that one of La Guardia’s most salient issues—immigration—was barely on their radar screen. Having grown up in the West and watched how Italian organ-grinders were mocked (kids would cry out, “A dago with a monkey!”), and having spent his career in the East combating the stereotype of the “crude wop,” La Guardia championed immigration reform. He wanted to remedy the abusive treatment of families at Ellis Island and change the restrictive quotas placed on southern and eastern Europeans. Learning that an Italian girl diagnosed with trachoma had been denied the right to a delayed deportation, which would have allowed her to return to Italy with her mother rather than alone, La Guardia sent a telegram to the secretary of labor, condemning the department’s action as “cruel, inhuman, narrow-minded, prejudiced.”

When, in 1924, nativists in Congress supporting the Johnson-Reed Act declared that “we have too many aliens in this country . . . we want more of the American stock,” La Guardia responded, “Is not this country made up of immigrants no matter what period of history you take?” By setting quotas based on immigration rates from 1890, the legislation ensured the drastic reduction of Italians and Jews. La Guardia fought to have quotas pegged to 1920 immigration levels, but the bill overwhelmingly passed by a vote of 323 to 71.

La Guardia detested the stereotype of the Italian organ-grinder. Growing up in the West, he had heard kids cry out, “A dago with a monkey!”

Fearless of special interests, La Guardia refused to cater to them. He supported a rent control bill despite the urgings of the powerful Real Estate Board of New York to vote against this “radical” act. The undeterred congressman wrote back, “I have read the arguments contained in your memorandum and it is the same old whining, cringing pleas presented by the New York landlords who have thrived on the housing situation . . . Nothing better in support of the bill could have reached the memberships of Congress than a protest from the landlords of New York City. Please keep up your good work.”

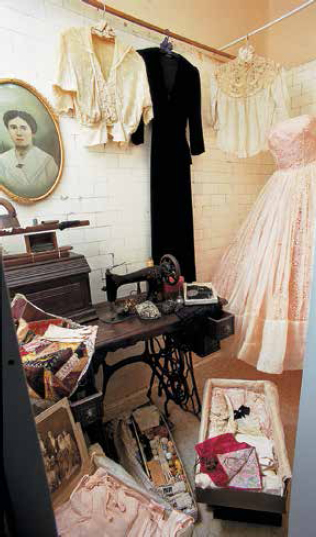

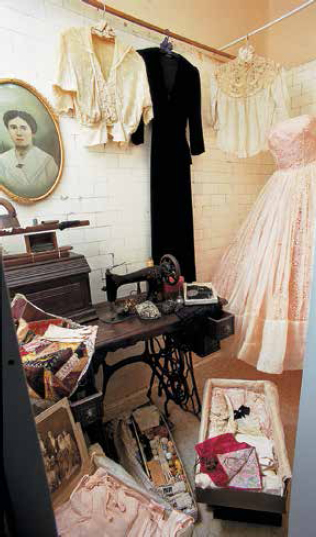

Many Italian-American women were talented seamstresses, and the ethnic group dominated the garment industry in the 1920s and ’30s. The black velvet dress and prom dress pictured here were designed and sewn by Nina Piscopo, a daughter of immigrants who had the good fortune of attending an art and design college in the 1930s.

Throughout the decade, La Guardia warned of the nation’s excessive inequality and sought to ameliorate rural and urban poverty. He introduced legislation to establish unemployment insurance. He advocated government ownership of power, railroads, coal, water, and oil to protect the public good over private profit. He was called a socialist and a radical, although his Old World values belied the second label. La Guardia could also be culturally conservative, especially toward the arts: he was suspicious of free-form jazz and modern art and dance, and preferred classical music and other more traditional art forms. While supportive of women’s rights, he had old-fashioned expectations of women as wives and mothers.

Such traditionalism was a luxury, however, for the majority of urban Italian-American women. In the 1920s, Italian Americans represented the largest group of women working in the manufacturing sector, and this number continued to grow in the following two decades, a time in which they dominated the garment industry. Seamstresses in factories, hat plume and piece workers at home—Italian-American women took needle to thread to help their impoverished families survive. As a congressman, La Guardia backed organized labor and joined workers on the picket line during the 1926 garment strike in New York.

La Guardia made fun of Prohibition, mixing two legal substances, drinking his homemade concoction, and waiting for the cops to arrest him.

La Guardia masterfully detected hypocrisy and shone best decrying it. He fought against the Volstead Act and continually made fun of it by mixing two “legal” substances at a drugstore—malt extract (with an alcoholic content of 3.5 percent) and near-beer—drinking his homemade concoction, and waiting for the cops to arrest him. Such theatrics, which he mastered throughout his career, illustrated the deeply troubling aspects of a law he found ridiculous. La Guardia understood that the rich and the middle class never lost access to alcoholic drinks—that Prohibition, as was intended, punished the immigrant masses and the working class. And he saw how young immigrants found bootlegging an easy way into illicit activity—a path that would haunt Italian Americans for decades.

After the 1929 stock market crash and subsequent bank run, the country entered the Great Depression and the economic promise of America vanished as if a vague dream. By 1932, the majority of the nation would come to agree with La Guardia’s views, favoring the kind of legislation that he supported but had been vetoed by Herbert Hoover. Ironically, with the public furious at the phlegmatic Hoover, a Democratic majority swept the country, ushering in Franklin Delano Roosevelt as president and his New Deal as policy—and voting a Republican congressman named Fiorello La Guardia out of office.

The despondent La Guardia returned to New York with his devoted secretary (now his second wife), Marie Fischer, upon the completion of the 1933 lame duck session of Congress. Within weeks he began talking about running for mayor. The first time La Guardia ran for mayor, in 1921, he was told, “The town isn’t ready for an Italian mayor.” Eight years later, trying again, he was called a “crazy little wop,” and the dashing and refined Jimmy Walker soundly defeated him.

Walker may have been elegant, but he was also a crook. Forced to resign in 1932 on charges of graft, he fled the country with his mistress. Now it was La Guardia’s turn to defeat the corrupt Democratic Tammany Hall. Once again he would have to solicit Republican backing, which meant the endorsement of a WASP gentry that had repeatedly rejected him. Or as one party leader said, “If it’s La Guardia or bust, I prefer bust!”

But through a combination of skillful maneuvering and a little luck, La Guardia became their reluctant choice. His political club in East Harlem served as the base to organize Italian Americans throughout the city. Vito Marcantonio ran the club, nicknamed the Gibboni (it took on this name after a baseball victory—someone called the group campioni, “champions,” and a member quipped that they looked more like gibboni—that is, gibbon apes).

Marcantonio, elected to the East Harlem congressional seat the same year that La Guardia became mayor, was, like his mentor, smart, progressive, and extremely hardworking. In their district office they listened to the problems of thousands of immigrants who marched each year through its doors seeking relief from their woes. Marcantonio, along with Leonard Covello and another East Harlemite, named Edward Corsi, was in charge of rallying the Italian-American base.

La Guardia (left) and his smart and liberal protégé, Vito Marcantonio.

Not that they had to do much convincing. The jubilant Italian-American population embraced Fiorello La Guardia and his message of social justice. Who better to clean up the slums than the man who had lost his wife and child to diseases contracted from tenement living?

La Guardia campaigned to convince the rest of the citywide electorate, who had grown used to an annual free turkey from Tammany Hall, that this cheap vote-buying trick meant little to their daily life. What they needed was good government and a benevolent welfare state—a city with balanced finances, which would make it eligible for federal money and the massive jobs program that President Roosevelt was creating. With Tammany in charge, the city would forfeit these funds because the federal government knew of its deep and pervasive corruption. The people needed a city in which tenements would be cleared for decent housing and parks built to rid the streets of their relentless urban blight.

On Election Day it became clear that Tammany wouldn’t give up without a violent fight. They sent out criminals and thugs wearing brass knuckles to intimidate and in some cases beat up the slum dwellers to support the Democratic candidate. Still, La Guardia won by over 250,000 votes. The overwhelming support of more than 300,000 Italian Americans enabled La Guardia to end the twenty-year reign of Tammany Hall.

La Guardia’s victory was a transformational moment in the history of New York and the identity of Italian Americans who, up until this time, held the least wealth, status, and power compared to other immigrant groups of equivalent size. Now they played a significant part in the political process. Tammany leaders, using taxpayer money for their personal trough, had nearly bankrupted the city’s finances. After La Guardia cleaned house and brought in top-notch commissioners, he restored the city’s credit rating, clearing the way for Washington to give New York badly needed New Deal money. The popular La Guardia became head of the United States Conference of Mayors, and his close connection to Washington brought billions of dollars to New York.

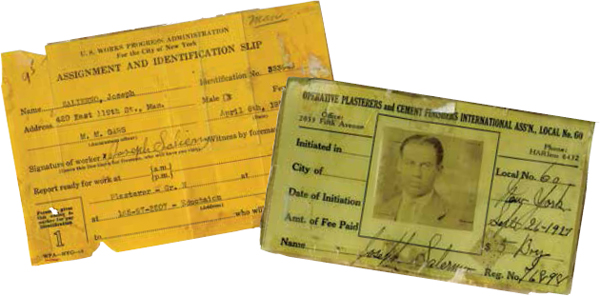

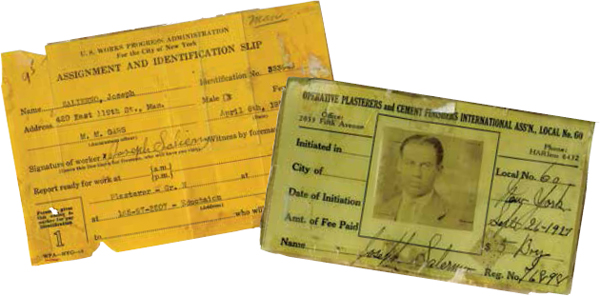

The money was desperately needed to repair a city still deep in Depression woes. Tens of thousands of people remained unemployed, and thousands more were starving and homeless. In 1935, Congress allocated $4.8 billion for President Roosevelt’s massive jobs creation program, the Works Progress Administration. La Guardia immediately began drawing up plans for $300 million in new projects, and New York became the first city to be awarded two hundred thousand WPA job slots.

The WPA gave employment to thousands of Italian Americans and placed them in jobs doing what they knew best: digging tunnels, drilling concrete, and laying bricks. These jobs in construction and other artisan trades gave Italian Americans a significant lift, and the means to enter a middle-class life. Because of the WPA programs, Italian Americans continued to contribute their talents to defining, in bricks and mortar, the visual texture of the city. Italian Americans already had sculpted some of the city’s most memorable landmarks, such as the stone lions guarding the New York Public Library, which La Guardia nicknamed “Patience” and “Fortitude,” created by the talented Piccirilli Brothers, whose workshop was located in the Bronx.

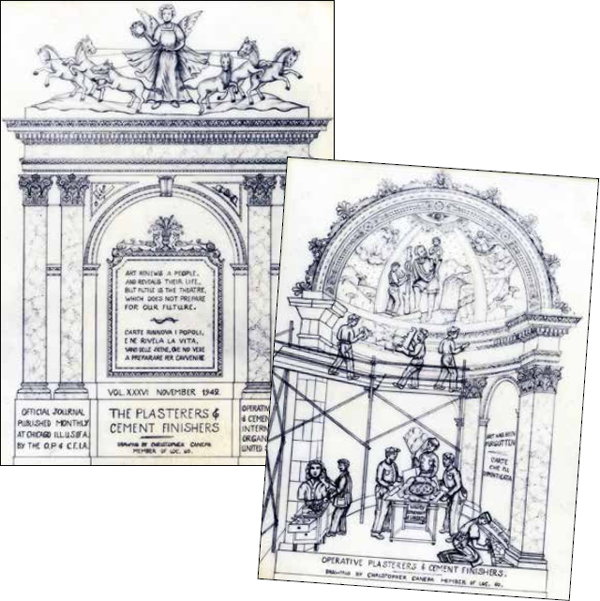

Plasterer’s union card and WPA assignment slip.

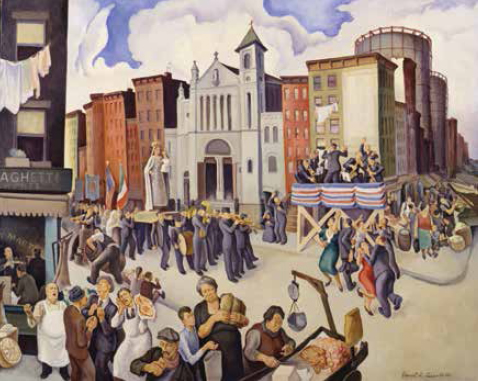

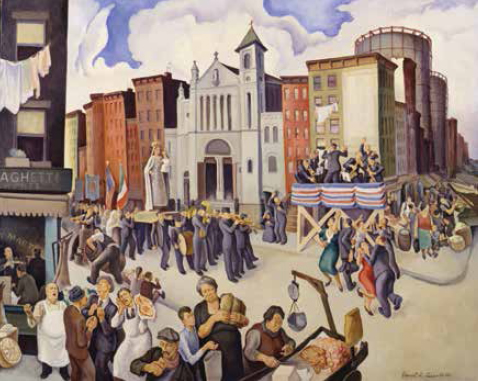

East Harlem artist Daniel Celentano, hired by the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), the precursor to the WPA, painted Festival in 1934, depicting the neighborhood’s annual festa.

With federal money pouring in through the WPA and other programs, the creation of New York as a modern, well-run cosmopolitan city began. La Guardia built the nation’s first public housing, along with bridges, tunnels, and the city’s first commercial airport, which would be named after him (La Guardia fondly called the project “the airport of the New World”). He established health clinics and created parks to give weary residents space to relax and breathe. He purchased privately owned subway lines to unify the city’s piecemeal mass transit system. He promoted symphony music, once even conducting the New York Philharmonic as its renowned leader Arturo Toscanini stood beside him. He created the City Center, which offered opera, theater, and the symphony at prices that ranged from twenty-five cents to a dollar, enabling the working-class to patronize the arts.

The famously hands-on La Guardia ran to fires with his own fireman’s helmet and read the comics over the radio to the kids during the newspaper strike. He created a legitimate police force, throwing out Tammany’s gang of bribed cops and significantly reducing crime. He took on organized crime, ordering the arrest of any known gangster who appeared in public, and he made a showy display of smashing slot machines and tossing them into the ocean. La Guardia understood that these rigged machines preyed on the poor, creating false dreams and draining them of the few dollars they had. He also continued his practice of taking political action to absolve private hurt. He was merciless toward Italian-American organ-grinders, removing them from the streets to rid the city of a stinging stereotype from his childhood.

Fiorello La Guardia served for three terms and, with his exhaustive list of accomplishments, remains the most effective mayor the city has ever had. His hiring policies, based on merit not political friendship, opened the doors for Italian and Jewish Americans to enter government, and eliminated barriers for the promotion of African Americans to supervisory positions. Fundamentally changing the perception of government from an excuse for graft to a force of good, he set a model for the nation. When he died of pancreatic cancer in 1947 at the age of sixty-four, New York experienced for the first time in over thirty years the shock of his silence, unable to imagine that their beloved Little Flower would no longer voice his passion for the city and its people.

La Guardia took on organized crime and made a showy display of smashing slot machines.

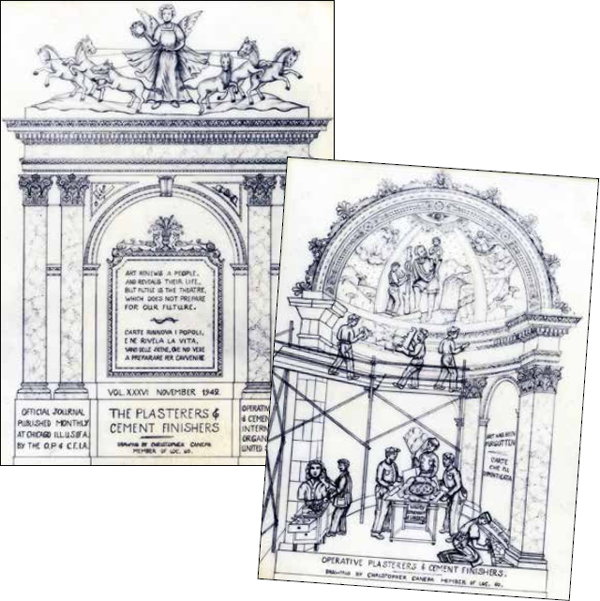

DOCUMENTI

ART RENEWS A PEOPLE

Italian Americans chiseled and sculpted many of the nation's leading landmarks (e.g. the figure of Abraham Lincoln at the Lincoln Memorial, carved by the Piccirilli brothers). Union workers celebrated their pride in craftsmanship, an Italian virtue they feared was threatened to become obsolete in America.