A Fascist gathering in New Jersey. Marginalized Italians felt that Mussolini could lessen their humiliations.

A Fascist gathering in New Jersey. Marginalized Italians felt that Mussolini could lessen their humiliations.

Columbus Day, the fall celebration that contemporary Italian Americans either gently note or easily forget, first became a federal holiday under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on October 12, 1934. The Italian-American bloc had become formidable—ushering in La Guardia as mayor the previous November—and Roosevelt, the consummate politician, understood the importance of recognizing the ethnic group’s emerging political and civic voice. The presidential proclamation represented a moment of great pride and growing confidence, yet coinciding with this new patriotism, a troubling nationalism was brewing in the Italian-American community. For over a decade, nonstop propaganda from a Fascist Italy had been saturating Italian-American newspapers, community centers, and after-school programs.

Columbus Day became a focal point that revealed clashes within the Italian-American community. In 1925, the dictator Benito Mussolini had made Columbus Day a national holiday in Italy, using the celebration to reaffirm the special nature of its people, descendants of the great Roman Empire. In the United States, throughout the thirties, Columbus Day brought with it bloody and violent confrontations between Italian-American Fascist sympathizers and a much smaller but belligerent coalition of anti-Fascist protestors. Governor Herbert Lehman presided over a ceremony at New York’s Columbus Circle in 1937, where more than five thousand people had gathered. Generoso Pope, the publisher of Il Progresso, the largest Italian-American newspaper in the country, and a fervent supporter of Mussolini, chaired the Columbus Citizens Committee. Many who gathered shouted “Fascisti!” and when Italy’s Fascist anthem, the “Giovinezza” (meaning “youth”), played, the massive crowd raised arms in the famous salute to the dictator.

Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, also on stage, gave a perfunctory and platitudinous speech praising Columbus and the contributions Italian Americans had made to the country. Later that day, La Guardia returned to the same platform to speak at a much smaller anti-Fascist event organized by his protégé, Vito Marcantonio. The second gathering, Marcantonio explained, was to support “the preservation and extension of democratic rights and civil liberties.”

Fascist sympathizers, like Pope, saw Columbus Day as a way to reaffirm the message of Mussolini. Anti-Fascist leaders, such as Luigi Antonini of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, saw Columbus Day as an opportunity to better recognize Italian Americans as part of mainstream American society, a group worthy of its own day. By 1938, Pope’s Columbus Day events were attracting upwards of thirty-five thousand people and routinely received the imprimatur of political leaders and the media. Many Americans viewed Fascism as the antidote to Communism, and as the New York Times reminded its readers, anti-Fascist gatherings included “Communists.”

La Guardia was caught in a political predicament: he despised the Italian dictator but didn’t want to offend the Italian-American masses supporting Mussolini. By the late 1930s, President Roosevelt found himself in a similar spot, afraid of offending the powerful publisher Generoso Pope and the votes his paper could deliver, but growing increasingly concerned about the situation in Europe. This fraught relationship between Pope and Roosevelt had international repercussions, thwarting the president’s initial attempts to stop the growing Fascist aggression in Europe.

It would be impossible to understand the adulation of the Italian-American masses for Mussolini throughout the 1930s without recognizing America’s initial enthusiasm for the dictator. After the “March on Rome” in October of 1922, in which hundreds of his followers demanded a Fascist government and the weak King Victor Emmanuel III relented, America was quick to celebrate Mussolini as a winner. Politicians, journalists, and businessmen believed that Mussolini’s new political program, with its brutal intolerance of strikes taking place throughout the country, would restore order and stem the tide of the growing Bolshevist threat.

Americans lapped up Mussolini’s rhetoric about restoring the greatness of the Roman Empire. Even the name of his party—the fasces, a bundle of wheat bound to an ax—symbolized Roman authority. Finally someone would impose structure on an undisciplined nation and make the trains run on time.

The magazine of Middle America, the Saturday Evening Post, praised Mussolini and serialized the dictator’s autobiography in 1928. The Chicago Tribune declared that Fascism represented “the most striking and successful attempt of the middle classes to meet the tide of revolutionary socialism.” Reporters like New York Times correspondent Anne O’Hare McCormick worked themselves up to a high pitch of adulation: “It is easy enough for Americans to comprehend the Fascisti. Direct action is intelligible in any language. A nation that thrilled to the Vigilantes and the Rough Riders rises to Mussolini and his Black Shirt army. They have done more to make Italy understood in the United States than three million Italians coming over to dig ditches.”

“A land of mothers is a land of sons, and the mothers of Italy have great power over their sons,” continued McCormick. “Mussolini himself is the son of a strong peasant mother, to whose devotion and self-sacrifice he is said to owe much. Women understand the old-fashioned, masterful sort of government which he re-establishes. They rally to the old-fashioned hierarchies, of religion, authority, obedience which he restores.”

The most nefarious aspects of Mussolini’s regime were still a decade away, but each of these journalists in the twenties turned their backs on the loss of Italy’s free press, its wrathful nationalism, the extreme violence of the Blackshirts who beat their opponents to death (or at a minimum beat and force-fed large doses of castor oil to any who showed disobedience), and the placing of faith in a man who radically and opportunistically changed his political positions.

Mussolini had been a fervent socialist and atheist journalist who denounced capitalists like John D. Rockefeller and J. P. Morgan in his articles about America. The young Mussolini wrote about the millworkers strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, sympathizing with the workers and condemning the “crimes of capitalism.” Once in power, however, he abandoned these positions, brutally suppressing strikes and embracing and winning the support of American capitalists and the Vatican. Eventually, the head of J. P. Morgan bank would become one of his most influential backers. The humorist Will Rogers, after interviewing Mussolini for the Saturday Evening Post, affectionately explained, “Dictator form of government is the greatest form of government; that is, if you have the right Dictator.”

America’s nativist prejudices played into this adoration. Elite Americans had always admired the beauty and artistic achievements of northern Italy, even if they found the people less diligent and hardworking than Anglo-Saxon stock. Now the moment emerged in which they believed Mussolini could mold an Italy that combined these achievements with their own more rigorous standards of work. It would take a dictator, so this thinking went, to accomplish such a herculean task.

Italian-American immigrants, typecast as stolid manual laborers or radicals (either “three million . . . coming over to dig ditches” or troublemakers like Sacco and Vanzetti), found solace in America’s embrace of the new Italian leader. Here was a man who could lessen their humiliation, illustrate their devotion to religion and country, and restore pride and glory to the Italy of their imagination. Nothing helps the confidence of a marginalized and maligned ethnic group more than recognizing that a new American idol is one of your own.

Mussolini was greatly preoccupied with how America saw him. The American press, for the most part, accepted the fact that the Italian government controlled the news and printed its own favorable versions of Italy’s progress and growth. But Mussolini found a way to spread his propaganda even more deeply through the Italian-American press.

Kansas City’s La Stampa, Philadelphia’s L’Opinione, Stockton, California’s Sole, Boston’s Gazzetta del Massachusetts, Chicago’s L’Italia, and Detroit’s La Tribuna d’America—all proudly served as propaganda machines, printing dispatches from the Italian news service controlled by Mussolini’s government. Pro-Fascist newspapers also promoted the creation of Italian language classes, which essentially became propaganda centers instituted under Mussolini’s orders to indoctrinate Italian-American youth. Parents, increasingly concerned that their children were losing ties to their homeland by not knowing Italian, enthusiastically signed up their children for these classes.

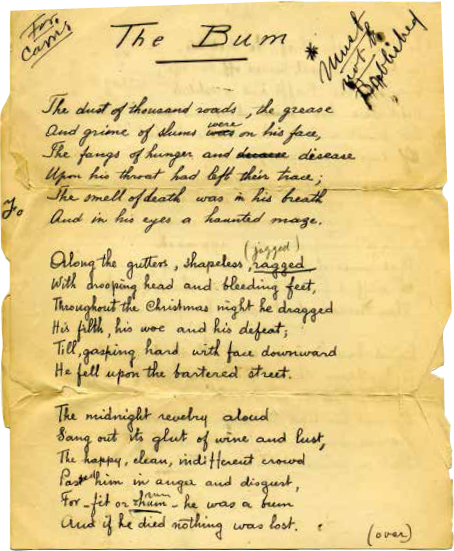

Meanwhile, the small anti-Fascist opposition, composed mostly of Italian-American labor groups, tried to get its word out under increasingly difficult circumstances. The Italian embassy alerted the US State Department about “the notorious Italian labor agitators Carlo Tresca, Arturo Giovannitti . . . and other social-communist elements in New York.” After Giovannitti’s imprisonment during the Lawrence strike, he continued to write political poetry and eloquently spoke out against Fascism, but his words, revered by the Italian-American left, never reached the masses.

In 1923 the Italian government tried to stop Carlo Tresca from publishing his leftist Italian-American newspaper Il Martello (“The Hammer”). The American government, concurring with the Italian embassy’s description of Tresca as an agitator, arrested and jailed him for publishing in Il Martello a two-line advertisement for a book written by a physician about birth control. The literary critic H. L. Mencken was so incensed by this assault on free speech that he ran the same ad in his magazine, the American Mercury, and, to no avail, challenged the government to arrest him. The mounting criticism of the government’s actions influenced President Coolidge’s decision to commute Tresca’s sentence of a year’s imprisonment to four months.

After Giovannitti’s imprisonment during the Lawrence Strike, he continued to write political poetry.

Of all the pro-Fascist Italian-American newspapers, the most important propaganda vehicles were San Francisco’s L’Italia, published by Ettore Patrizi (both A. P. Giannini’s Bank of America and Di Giorgio Fruit Corporation bought ad space in this publication), and New York’s Il Progresso Italo-Americano, which had the largest national circulation.

Generoso Pope had come to America from southern Italy penniless. As a young man he had hauled water to workers in New York City building the Pennsylvania Railroad, worked his way up to foreman, and eventually made his fortune as the owner of the Colonial Sand & Stone Company, the largest supplier of sand and gravel in the country. Along the way he befriended gangsters like Frank Costello, who was godfather to one of Generoso’s sons.

In 1928, Pope bought Il Progresso for over $2 million. Before he purchased the paper, the Italian ambassador and counsel general both became personally involved with the sale, each expressing concern that the paper needed to fall into sympathetic hands. They had nothing to worry about with Pope; he accepted its “free telegraph service,” went to Italy to receive a private audience with Mussolini, and faithfully printed Fascist falsehoods until 1941.

Pope also helped organize one of Mussolini’s biggest propaganda stunts in the United States: the overseas flight of the Fascist air marshal Italo Balbo. In 1933, during a time when trips across the Atlantic were still considered perilous, Balbo led a squadron of twenty-five seaplanes flying to Chicago’s World’s Fair. On the shores of Lake Michigan, tens of thousands of Italian Americans eagerly waited to see the fleet’s pageantry as it flew in a perfect V formation. Balbo then headed to New York, where he would be welcomed by two million people with a ticker tape parade organized by Pope, followed by a lunch at the invitation of President Roosevelt. The Italian-American masses, thrilled at this American recognition of Italian strength, listened rapturously as Balbo used the opportunity to reinforce Mussolini’s key propaganda message: “Be proud you are Italians,” he told the cheering crowd. “Mussolini has ended the era of humiliations.”

Italian Americans believed that Fascism celebrated the glory of being Italian. “You’ve got to admit one thing,” a young anti-Fascist Italian-American woman observed at the time. “He has enabled four million Italians in America to hold up their heads, and that is something. If you had been branded as undesirable by a quota law, you would understand how much that means.”

But what Italian Americans didn’t know, watching Balbo’s show and expressing a love for the motherland, was the increasingly militaristic and oppressive nature of the regime. Mussolini, now known as Il Duce (“the leader”), directed his secret police to spy on and imprison dissenters—or the next-worst fate, exile them to southern Italy. Militaristic Fascist rallies took place each Saturday for schoolchildren because Mussolini wanted to condition every child and citizen to prepare for a perpetual state of war. And still, President Roosevelt welcomed Balbo to the United States and called Mussolini “that admirable Italian gentleman.” The following year, Fortune magazine ran a feature praising Fascism’s “ancient virtues” of “discipline, duty, courage, glory, and sacrifice.”

Only when Mussolini invaded Ethiopia in 1935, his first step in restoring Italy to the greatness of the Roman Empire, did Americans take a second look. When Ethiopia’s leader, Haile Selassie, pleaded for the world’s help, America was shocked to learn about the Italian dictator’s dive-bombing raids and use of mustard gas on the Ethiopian people. Yet, conservative publications like Henry Luce’s Time magazine still had plenty of laudatory words for the dictator. The readers of Time learned that “Mussolini is a spellbinder . . . [He] is more controlled, more disposed to reticence, less expansive than the average Italian . . . He gives the impression that confidence will be well placed in him, and power turned to good uses . . . It is this un-Italian steadiness which marks him off from the rest.”

Italian Americans continued to buy this kind of praise. When Mussolini declared a “Day of Faith” in Italy, telling every woman to give up her gold wedding ring to raise money for the country’s war efforts, rallies were held in Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston, and New York. Italian-American women handed over their precious gold wedding bands and in return received steel ones blessed by local parish priests. Generoso Pope led a huge Madison Square Garden rally in support of the war, declaring that he had sent a check of $100,000 to Mussolini’s government in Rome.

Roosevelt wanted to stop the aggression and agreed with the League of Nations’ decision to impose economic sanctions on Italy, calling for a “moral embargo” on trade. Generoso Pope, most likely working with the Italian embassy, ran a campaign in Il Progresso urging Italian Americans to protest the embargo, including a template protest letter. The government was barraged with tens of thousands of letters, and Roosevelt backed down. While the United States didn’t ship weapons, it continued to send exports to Italy.

Nonetheless, Roosevelt refused to recognize Italy’s conquest of Ethiopia. Republicans tried to capitalize on his position, telling the Italian-American community not to reelect a man who refused to support Italy and instead backed the wishes of African Americans to support Selassie. These two communities, which had coexisted, if at times uneasily, now found themselves political enemies. Combined with the Depression and competition for jobs, neighborhoods like East Harlem became rife with racial taunts, street brawls, and an increased police presence in the streets.

Mussolini was stripping away civil liberties in Italy, but many Italian Americans remained blind to his actions.

Mussolini personally told his Italian-American mouthpiece, Generoso Pope, that Italy would not discriminate against Jews, and the publisher dutifully reported the dictator’s words. Yet Italian Jews soon discovered the reality behind Mussolini’s blatant lie as their rights were slowly eroded. By the time Mussolini’s racial laws fully came into effect, Jews had been stripped of their citizenship and prohibited from public jobs, skilled professions, and schools.

Even Generoso Pope couldn’t accept the 1938 racial decrees, and while he continued to support the dictator, he criticized Mussolini’s regime for the first time in decades. With atrocities rapidly taking place in Europe, in the following years anti-Fascist Italian-American groups finally began gaining ground against pro-Fascist publications. In California, anti-Fascists took on San Francisco’s L’Italia; Carlo Tresca continued to devote his energies to writing against Pope and denouncing Mussolini; and Carlo Sforza, a former count and foreign minister, became a leading member of the anti-Fascist Mazzini Society (founded in 1939 by the historian and Italian exile Gaetano Salvemini), and had the ear of top members of Roosevelt’s administration.

President Franklin Roosevelt (left) and Il Progresso publisher Generoso Pope. In 1941, FDR finally insisted that Pope rein in his support for Fascism in the Italian-American press.

Fiorello La Guardia, fed up with the Fascist propaganda in Il Progresso, decided it was time to play hardball with Generoso Pope, whom La Guardia referred to as a cullo di cavallo (“horse’s ass”). He asked the FBI to investigate Pope’s tax returns and grill him about his Fascist activities. The FBI balked until Roosevelt granted his permission. In 1941, Roosevelt asked Pope to come to Washington for a private meeting and told him that it was time to rein in his support of Fascism. Whatever FDR said, or threatened, during the meeting, Pope stopped praising Mussolini in his editorials and finally, several months before Pearl Harbor, denounced Mussolini in Il Progresso in both Italian and English.

Not until Mussolini attacked France in 1940 did the majority of Italian Americans begin to understand the regime’s brutality and the true meaning of Fascism. For a year the community waited in fear, worried about the events taking place in Italy, and wondering if America would enter the war. Four days after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, on December 11, 1941, they received their answer: Mussolini, standing on the balcony of Rome’s Piazza Venezia, declared war on the United States, forever ending the decade-long romance with America and Italian Americans.

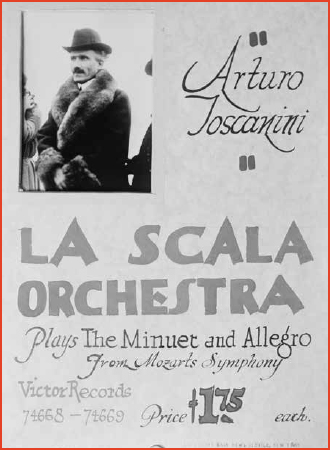

After Mussolini’s March on Rome, Arturo Toscanini—then fifty-five years old and considered one of the most illustrious conductors in the world—was not impressed. As most of Italy and America embraced the daring of the would-be dictator, Toscanini reportedly said to a friend before the march that if he were capable of killing a man, he would kill Mussolini.

Toscanini had met Mussolini in 1919, and even briefly flirted with a form of radical socialism that Mussolini first supported. Toscanini’s roots were antimonarch—his father, Claudio, had been a soldier under Garibaldi and had fought among the Thousand in Sicily. Arturo, perhaps inheriting his father’s political sense, feared Mussolini’s ambitions earlier than others, and as an artist he inherently understood the dangers of authoritarianism to freedom of expression.

Toscanini had a famous temper to match his perfectionism, and he refused to tolerate the slightest bit of laziness or slack on the part of musicians or staff. His embrace of rigor and excellence in pursuit of artistic freedom would clash magnificently with Fascism’s crudity and heavy-handedness. From the earliest days of Mussolini’s rule, Fascists began requiring that the “Giovinezza,” the party anthem, be played during concerts. In one performance of Falstaff at La Scala, members of the audience demanded the “Giovinezza” before the third act. The conductor refused and their chants continued, leading Toscanini to smash his baton and leave the pit.

Toscanini’s renown enabled him to escape the Fascist stranglehold, and he traveled often to America, serving as a conductor for the New York Philharmonic and the Metropolitan Opera. It wasn’t until 1931 that Toscanini’s position would have personal repercussions, after Mussolini wrote into law that the “Giovinezza” had to be played at public events. When the sixty-four-year-old conductor refused to play the anthem for a concert in Bologna, Fascist thugs surrounded and attacked him outside the theater, punching him in the face and neck. In the next years, life became intolerable for Toscanini, whose phone was tapped and movements monitored by the secret police.

A well-timed offer provided another opportunity to live and work in America. Trying to improve its radio content, the National Broadcasting Company invited Toscanini to create and conduct an orchestra for weekend broadcasts. Beginning in 1937 on radio and lasting until 1954 on television, Toscanini was America’s “maestro,” conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra. The first classical conductor to become a household name, Toscanini brought the music of Verdi, Wagner, Vivaldi, Brahms, and Beethoven into millions of homes. Combining technical perfection with bold imagination, he famously elicited brilliant performances from his musicians.

Toscanini enraptured American audiences, but his defiance of Mussolini continued to endanger him. During one of his return trips to Italy, Mussolini, furious that the conductor had traveled to Palestine in protest of the newly implemented racial laws, seized his passport. Friends feared imprisonment or death, and a Swiss journalist seeking to help posed as a Fascist informer. The journalist suggested that the American press was on the verge of learning about Mussolini’s actions. Il Duce, still concerned about his image in America, fell for the ruse and had Toscanini’s passport returned.

Returning to New York, Toscanini settled permanently in the Riverdale section of the Bronx. On July 25, 1943, an announcement interrupted one of his NBC broadcast concerts: Mussolini had been toppled. The aging conductor clasped his hands and looked to the heavens.