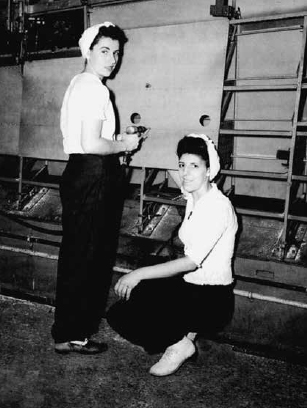

Albert Onesti (left) had second thoughts about the enemy after visiting his family’s ancestral village.

Albert Onesti (left) had second thoughts about the enemy after visiting his family’s ancestral village.

In schoolyards, kids booed Italian boys, called them “Mussolini,” and flung the words “dago” and “wop” as easily as brown-bag lunches. For older boys, wearing the uniform of the US military was the ultimate show of patriotism, and huge numbers of Italian Americans answered this call by enlisting. Even more responded dutifully to the draft. By 1942, US Attorney General Francis Biddle acknowledged that half a million Italian-American men were serving the country, a high percentage for an ethnic group numbering five million. The Italian-American newspaper Il Progresso now performed a 180-degree turn, trumpeting the call of American patriotism against Fascist Italy, and featuring page after page of Italian Americans participating in the war effort. The war had tested the meaning of the hyphen, and the answer was clear: one’s heritage might be Italian, but one’s allegiance was to America.

Ambivalence, however, coincided with this allegiance, causing Italian Americans much grief. As author Jerre Mangione wrote in his memoir An Ethnic at Large:

Anxiety was a common trait of all my relatives, myself included, and the war worried them as nothing else in the United States ever had. Even the years of the Depression, when many of them lost their homes to the banks, were not as fraught with anxiety. It worried them that their adopted country, the birthplace of their children, was at war with their native land, dropping American bombs on their own kin. They worried that their sons might be drafted, killed, wounded, or taken prisoners, all of which was happening with increasing frequency. They were not the only ones in the nation who had such worries, of course, but their capacity to emotionalize their anxieties seemed to surpass that of any other people I knew, and I could not help wondering if this was a peculiarly Mediterranean legacy of theirs, an instinctive anticipation of tragedy germinated through the centuries by frequent traumas and tears. In any case, their worries loomed distinctively large and black compared to the general mood of the nation which was bizarrely optimistic.

But lingering doubts and dark fears had to be kept private, or among closest family, certainly not shared with the larger population. This “two-ness” dilemma, as it was labeled, affected many second-generation Italian-American enlisted men, as well as those who watched their brothers and neighbors sent to Italy. Alberto Onesti, a World War II private, articulated this predicament more than seventy years later as he recalled his basic training in South Carolina in 1943. His superiors had asked if he would have any objection to killing Italian soldiers. “Absolutely not,” Onesti had replied. “He’s wearing a different uniform than I am. I don’t care if he’s Italian, Polish, German. I’m going to kill him.”

The answer satisfied the commanding officers, who sent Onesti to Italy. But upon reaching the same roads once traveled by his ancestors, Onesti’s initial reaction grew more nuanced. He decided to track down his family’s former village in Umbria and met a man who asked Onesti what town he was looking for. “Olveto,” Onesti responded, prompting more questions from the man. “He heard my name and he went crazy. He says, ‘we talk about you all the time.’ The whole town came out—they gave me such a welcome. You can’t ever believe it, like a hero walked in. I met my aunts, my cousins. I still was against Mussolini and Fascists. But I had a whole family out there.”

As Italian-American soldiers grappled with this dilemma, at home the ethnic group worked hard to suppress anything that announced one’s “Italianness.” Along with the Germans and Japanese, Italians spoke the “enemy’s language,” and the FBI had been monitoring Italian publications because so many of them had been pro-Fascist. One result of this intense scrutiny was that the Italian language and its numerous dialects, once part of the polyglot of America, began to fade. Italian-American newspapers changed the names of their publications to English or stopped publishing altogether; store owners put up signs announcing, “No Italian spoken for the duration of the war”; and the number of high school and college Italian language classes dropped precipitously.

Italian Americans understood that to be American meant helping with the war effort, and they found many ways to contribute. At home, Italian-American women, with their dominant presence in the garment industry, worked tirelessly in large cities around the country. Many of them were employed by Italian-American dress and suit store owners who manufactured and supplied uniforms to the GIs, specializing in popular styles like the short-cut Eisenhower jacket.

Italian-American merchants showed their support for the war effort. Some even posted signs announcing that Italian couldn’t be spoken for the duration of the war.

The US military approached the Italian immigrant chef Ettore Boiardi, who had been mass-producing his own sauces and spaghetti, to provide supplies for the servicemen. His factory employees, working seven days a week in twenty-four-hour shifts to produce enough spaghetti, meatballs, and tomato sauce, became the largest supplier of rations to US and Allied troops. Boiardi’s company also made other items popular with the troops, like ham and eggs and hot dogs, and it supplied fat-laden staples to the Russians to get them through the harsh winters. The American troops liked the canned pasta and sought it out once the war was over, finding the product under its easier-to-pronounce phonetic label: Boy-Ar-Dee.

Il Progresso found its new mission in promoting Italian-American war efforts and regularly ran features of newsworthy men and women. The newspaper introduced readers to Margaret Ferrone, inventor of a machine that accelerated the production of fuses used to detonate bombs; Teresa Daniello, who wrote not only to her five sons in service but to their fellow servicemen as well, penning thirty-two hundred letters; and Carmela Zarillo, a senior citizen who repaired asbestos gloves for factory workers.

Italian Americans even gave the country a “Rosie the Riveter.” As the song of the same name played on the radio and the “We Can Do It!” poster—whose iconic face later became known as Rosie the Riveter—inspired women to join the war production effort while the men fought overseas, Rosina (“Rosie”) Bonavita was working at a GM plant in Tarrytown, New York. Her future husband had joined the navy, three of her brothers were in combat zones, and Rosie saw it as her duty as a riveter to assemble war equipment at record-breaking speed. Morale in the plant had been terribly low, and, according to her son, Rosie decided to “perk everyone up” with some assembly-line wizardry. She and her partner set a national record in 1943 for building the wing of a Grumman Avenger torpedo bomber. Between the hours of midnight and 6:00 a.m., Rosie and her partner Jennie Fiorito, bandannas tied around their heads like the determined woman in the famous poster, drilled over nine hundred holes and drove in 3,345 rivets to assemble the bomber’s wing. Another pair of riveters eventually broke this record, but Rosie was not one to give up her title. She set a new speed standard, assembling a wing in a mere four hours and ten minutes with another partner, Susan Esposito. Bonavita, however, always disliked the iconic image of Rosie the Riveter that was depicted in the “We Can Do It!” poster, designed to inspire women to join the war production effort. She said that she never had those kinds of muscles.

Rosina (“Rosie”) Bonavita, Italian Americans’ own “Rosie the Riveter” (right), saw it as her duty to assemble war equipment at record-breaking speed.

A few prominent Italian Americans aided the war effort by trying to coax Italians to join the Allies. The Roman-born journalist Natalia Danesi Murray worked at NBC studios and broadcast The Italian Hour via shortwave radio to Italy. Murray began her broadcasts earlier in the dictator’s regime to expose Mussolini’s oppression and to introduce an American voice to Italy (conductor Arturo Toscanini was a frequent guest on her radio show). After Italy declared war on the United States, Murray reminded Italians of their close ties to America and their many relatives here, trying to win their support for the Allies. Mussolini’s team branded Murray “the voice of Italo-American anti-Fascism.” Her son, the writer William Murray, nicknamed his mother “Tokyo Rosa.”

Italian Americans showed their patriotism at World War II parades.

Similarly, New York’s indefatigable mayor began a shortwave radio program, Mayor La Guardia Calling Rome, in which he roused Italians to free themselves from the Fascist yoke of Mussolini. Beginning and concluding each broadcast with the words “Patience and Fortitude,” La Guardia spoke enthusiastically about American advances while encouraging the Resistance by telling Italians that Hitler intended for their country to fall so that he could assume control of its machinery, ships, and industry. La Guardia’s exhortations were extraordinarily popular among Italians yearning for a voice from America.

The filmmaker Frank Capra joined American propaganda efforts, putting together a series of films for servicemen called Why We Fight. Capra’s films were careful to exclude traditional stereotypes and took the point of view that Mussolini, not the Italian people, was the enemy to be stopped.

There were also many Italian-American war heroes, and the pages of Il Progresso well documented their deeds: the ace pilot Don Gentile from Ohio; the Minnesotan Willibald C. Bianchi, among the first servicemen to win the congressional Medal of Honor fighting in the Pacific; New Jersey war hero John Basilone, who plowed through Japanese enemy fire to rescue two other marines; and Californian Allen V. Martini, a World War II pilot who dubbed his plane the “Dry Martini” and was credited with shooting down twenty-two Nazi warplanes in only fifteen minutes.

The singer Tony Bennett, who served in World War II, with his mother.

The government, reaching out to Italian-American anti-Fascist organizations, also recruited Italian Americans for secret intelligence missions. One of the largest operations took place in Sicily, where Italian-American soldiers used their knowledge of the language, customs, and local dialect to gather information. The Sicilians, much more comfortable with the presence of Italian Americans than that of German troops, provided the men with invaluable information as the Allies ultimately liberated Sicily.

Italian-American wives waited patiently while their husbands served in the US military. In this photo, an Italian-American mother celebrating the second birthday of her son placed a picture of her husband stationed in the South Pacific on the table.

The Battle of the Bulge and the Battle of Normandy in Europe, Guadalcanal and Iwo Jima in the Pacific—in all the major battles of World War II, Italian Americans played vital roles. When, on September 2, 1945, the Allies declared the war officially over, Italian Americans, overwhelmed with joy and finally seeing an end to years of oppressive anxiety, welcomed back their fiancés, husbands, and sons.

The war broadened the lives of servicemen in ways previously unimagined. Sent across the world, they learned foreign customs and saw exotic lands, perhaps for the only time in their lives. Some married European and Asian women; others took advantage of securing an education or a coveted home through the GI Bill. Italian Americans would also need to put behind them the jeers they had heard and marginalization they had experienced during the lowest point in their New World history, but now their American identity felt more tangible than ever.

With Italy’s surrender, Italian Americans were joyful, welcoming back their fiancés, husbands, and sons.

Second-generation Italian-American mothers, accustomed to their mammas rolling dough for the pasta, usually harrumphed at their children’s request for Chef Boy-Ar-Dee canned ravioli, America’s version of Italian food. Did they realize that beneath the white toque on the label was a talented immigrant Italian chef who had begun his career making a sauce that used only imported olive oil and Parmesan cheese?

Ettore Boiardi was a fifteen-year-old orphan in 1914 when he came to America from Piacenza in Emilia-Romagna, today considered Italy’s leading food region. His older brother Paul had found a job as a waiter at New York’s Plaza Hotel and soon became maître d’ of the hotel’s stylish Persian Room restaurant. He sent for his brothers, Ettore (who would anglicize his name to Hector) and Mario, both eager for a fresh start in the New World. Paul found Ettore work in the hotel kitchen, which started him up a ladder of jobs that included sous-chef at a New York Italian restaurant called Barbetta; a stint at the Greenbrier hotel in West Virginia, where he catered the large wedding for President Woodrow Wilson’s second marriage; and head chef at a hotel restaurant in Cleveland, the city he would make his permanent home.

In 1924, Hector opened his own restaurant on the side, Il Giardino d’Italia. The customers loved the fresh ingredients in his sauce, and Hector began making them take-home packages: he poured the tomato sauce into glass milk bottles, wrapped up some dried spaghetti, and threw in a container of Parmesan cheese. Soon he realized the potential market for the jarred sauce, and with his two brothers he formed the Chef Boiardi Food Company. The triple vowel combination proved too difficult for Americans, so they changed the name to its phonetic spelling, Boy-Ar-Dee (Americans emphasize the last syllable, while Italians stress the penultimate).

In 1936 they moved the plant to Milton, Pennsylvania, the home of an abandoned silk mill. The brothers chose the predominantly German town to be near acres of farmland, space to grow enough tomatoes to process twenty thousand tons of sauce a season. At the company’s height, it produced 250,000 cases a day, sold exclusively through the A&P super-market chain.

After the war, the Boiardi brothers sold the company to the American Home Foods Company. The market had already demanded that the Boairdis use less expensive ingredients than imported olive oil and cheese, but with increasing mass production, the Chef Boy-Ar-Dee brand came to mean the goopy canned goods lamented by Italian-American mothers, stunned that anyone would consider this Italian food. No wonder kids in the 1980s taunted Anna Boiardi, Hector’s great niece, for her “weird” lunches when she brought mozzarella, prosciutto, and tomato sandwiches to school, made by her Italian-born mother.

Hector continued to advertise Chef Boy-Ar-Dee to millions of Americans up until the 1960s. In a 1953 commercial, he peers through an open door to announce, “Hello, may I come in?” part of the intimate approach that made the brand a household name.

Gay Talese, who was born in 1932, is the best-selling author of eleven books. His book Unto the Sons traces the origins of his family, who emigrated from the town of Maida in southern Italy. Talese recounts the stigma of an Italian-American childhood during World War II and the dilemma of dual loyalties that his father, who worked as a tailor in Ocean City, New Jersey, experienced during those years.

Gay Talese, who was born in 1932, is the best-selling author of eleven books. His book Unto the Sons traces the origins of his family, who emigrated from the town of Maida in southern Italy. Talese recounts the stigma of an Italian-American childhood during World War II and the dilemma of dual loyalties that his father, who worked as a tailor in Ocean City, New Jersey, experienced during those years.

Q: You had relatives in Italy fighting the war?

Talese: I had Italian uncles who were in Mussolini’s army, and the only reason I knew that was because on my father’s bureau in his bedroom, there were pictures of these two brothers. In 1942 and 1943, they were fighting the Americans who were invading at that time the southern part of Italy by way of North Africa.

Q: How did your father feel about all of this?

Talese: Well, he spoke to my mother, not to me, not to my younger sister, but to my mother. He would express a certain misgiving about what his mother and other female relatives must be under-going, the sisters or wives of those people who were in the army. He would then reveal his affiliation and his concerns about his native country, as he would not during the daytime in the presence of anyone in the store, including the two employees they had. In the privacy of their apartment, they were more candid and more revealing of their place in society and their fears about where their ancestral traces were.

Q: He was concerned about revealing these feelings to others who weren’t Italian?

Talese: He became a citizen in 1928, but he didn’t feel that he was a citizen. He’d felt maybe before the war he was, but during the war, he felt he was on trial. He felt he was a marginal American citizen, a half American citizen, and he had to behave himself, and he did.