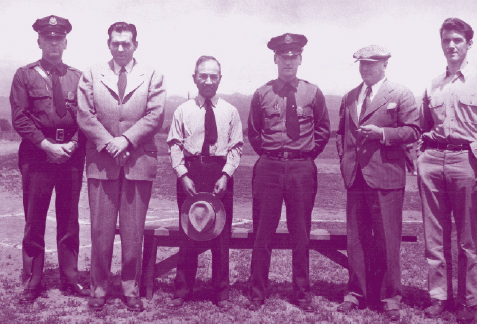

Six hundred thousand Italian Americans were registered as enemy aliens, 1,500 were arrested, and over 250 were kept in internment camps like this one in Missoula, Montana, for the duration of the war.

Six hundred thousand Italian Americans were registered as enemy aliens, 1,500 were arrested, and over 250 were kept in internment camps like this one in Missoula, Montana, for the duration of the war.

Italian-American servicemen fought in record numbers for America abroad, but at home the US government deemed the parents of many of these soldiers “enemy aliens” and restricted their parents’ civil liberties. The servicemen considered the government’s decision nonsensical at best, destructive and demoralizing at worst.

More than a year before Pearl Harbor, the government, fearing war might be imminent, created the Alien Registration Division to register and fingerprint Americans who had never gone through the process of becoming citizens. Not wanting to alarm millions of aliens in the country (with Italian Americans representing the largest number of them), the government tried to soft-pedal the process, urging celebrities who were noncitizens to register and changing registration centers to post offices rather than the originally designated police stations.

The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Proclamation 2527, which rendered the country’s six hundred thousand unnaturalized Italians enemy aliens, subjecting them to restrictions, apprehension, and detention (another proclamation was similarly issued against German nationals), and requiring them to carry pink identification cards.

The War and Justice departments decided that any Italian who lived here for decades but did not seek citizenship performed an inherent act of disloyalty. Yet the majority of immigrants in that category were illiterate, and many still lived in isolated ethnic conclaves where they never learned English, the essential prerequisite for passing a citizenship test. Hundreds of thousands of these enemy aliens were mothers and grandmothers, women who saw the purpose of their lives as cooking, cleaning, and caring for their children to help them live the promise of this new land.

Deemed an enemy alien because she never applied for citizenship, Celestina Stagnaro Loero was forced to move from her home for the duration of the war.

Restricted from traveling more than five miles from their homes without permission, enemy aliens had to report to the police a move in residence or change in job. They needed to surrender to the local police office shortwave radios and cameras, two items on a list of contraband. Their homes were subject to spot searches, and violation of any of these restrictions carried the risk of arrest. Nearly three thousand spot searches took place (mostly in New York, Pennsylvania, California, and Louisiana), over 1,500 Italian Americans were arrested, and more than 250 were kept in internment camps for the duration of the war.

Along the Pacific Coast, the War Department forced an estimated ten thousand Italian Americans to move from their homes near strategic waterfront areas and subjected another fifty thousand to a strict 8:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m. curfew. The government’s actions, especially the forced relocation of elderly residents, treated grandmas as if they were spies sautéing bombs for the gravy or packing pistols in Sunday purses, alongside the rosary beads. Terrified families feared what the next step might be. In the weeks preceding the relocation program, four Italian men committed suicide. Italian Americans only narrowly escaped the plight of the Japanese in internment camps—also originally planned for Italians and Germans. A 2001 report to Congress admitted that much of the information about the treatment of Italian Americans during World War II remains classified and “never acknowledged in any official capacity by the United States government.”

At the time, many believed that a fifth column existed in the United States that was taking its orders from “Roberto”—that is, Rome, Berlin, and Tokyo. Since 1936, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had been compiling a “Custodial Detention List,” which categorized potential security threats. Roosevelt gave the FBI permission to arrest anyone on Hoover’s list without the protection of the Bill of Rights. When the police came knocking on doors, they stated simply that it was “by order of President Roosevelt.”

Teachers at schools that taught Italian (once supported by Mussolini) and World War I veterans, known as ex combattenti, were marked as dangerous subversives, some sent to internment camps or forced to relocate hundreds of miles from their homes. Filippo Molinari, who sold subscriptions for San Francisco’s pro-Fascist newspaper L’Italia and was a World War I veteran, was taken from his home on the same night of the Pearl Harbor attack. Wearing only slippers and a thin garment, Molinari was put on a train to Missoula, Montana, isolated, unable to contact anyone, and freezing as the midwestern temperature dipped far below zero.

For West Coast Italian Americans, this government treatment must have come as a particular shock. California Italians had been a great immigrant success story earlier in the twentieth century; many had secured a place in the American power structure. But the man placed in charge of the War Department’s Western Defense Command, Lieutenant General John DeWitt, was a militaristic bureaucrat determined to treat Italian and German Americans as badly as the Japanese. Convinced that a large number of fifth columnists existed in each community that could sabotage key military areas and bridges, he vetoed the more moderate plans of the Justice Department. DeWitt persuaded Roosevelt to relocate Italian Americans who were living in what he considered “restricted” zones of the West Coast.

The Western Defense Command announced in January 1942 that it had created eighty-six prohibited zones affecting almost the entire Pacific Coast—from the Pacific Ocean to the Sierra Nevada. The next month, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the army to exclude anyone it chose from these restricted areas. In the counties of Monterey and Santa Cruz, thousands of Italians west of Highway One had to move. In Pittsburg, California, a third of the residents, nearly three thousand people, were forced to leave their property. In San Francisco, Fisherman’s Wharf and other areas near the water were off limits to aliens.

Italian-, Japanese-, and German-American internees stand with officers in Missoula, Montana. Without the protection of the Bill of Rights, police could haul enemy aliens away to internment camps following a mere knock on the door.

The government moved Italian-American noncitizens a few blocks from waterfronts, steel companies, and other production facilities. DeWitt’s initial plan went well beyond this relocation, which took place two months before the internment of the Japanese. He intended to put the Italians and Germans in camps as soon as the Japanese had been cleared from the area.

Many ludicrous elements defined this quickly implemented policy, beginning with the premise that moving nearly ten thousand Italian Americans a few blocks from where they lived would be in the interest of national security. In addition, if one parent was a citizen and the other an enemy alien, the citizen could stay in the home but the alien had to move. In one case, a man could no longer enter his business—a pool hall and soda fountain located in a restricted area of Eureka in northern California—so he stood across the street (which wasn’t restricted) and yelled instructions to his son on how to keep things running. If a doctor’s office was located on the restricted side of the street, a permit from the local police office had to be obtained before an enemy alien could get medical attention.

For preternaturally anxious Italians, their worst fears vividly unfolded before them. Reading the newspaper meant learning they had to leave homes often built with their own hands. With scant information, people didn’t know if they would ever return. Some families stayed with relatives, but others futilely searched for places to live because many landlords wouldn’t rent to enemy aliens. Being old and poor meant moving to ramshackle houses and waiting for further news of one’s fate.

Fishermen suffered terribly. Since the late 1900s, when they had begun supplying food for the California coast, these men, many illiterate, had tested their command of choppy waters, not the English language. Having secured steady work, they never imagined learning to read and write in English to prepare for a citizenship test (in the era before Social Security and Medicare, there were few benefits to being a citizen). Enemy aliens could not step onto wharves, piers, or their beloved fishing vessels.

Many Italian-American fishermen were unnaturalized citizens, now deemed enemy aliens. Because of this status, they could not step onto wharves, piers, or their own vessels.

Giuseppe DiMaggio, the father of Joe DiMaggio, was a Sicilian immigrant who had come to America in 1898 and brought his wife Rosalie several years later. Like so many Californians of Sicilian origin, he worked as a crab fisherman while Rosalie raised their nine children. Neither could read or write. Their home on a hill above Fisherman’s Wharf didn’t fall in the restricted zone, but because of Giuseppe’s enemy alien status, he could no longer work on the wharf or enter his son Joe’s restaurant. Giuseppe’s specialty, spicy crab cioppino—a fish stew invented in San Francisco—which he liked to prepare for Joe’s friends, was now officially off the menu.

Yet just the year before these restrictions, Joe DiMaggio had given the nation its summer pastime as they watched “Joltin’ Joe” pop home run after home run in a remarkable fifty-six-game hitting streak for the Yankees. While his panicky government declared his parents enemy aliens, Joe left the Yankees to fight in the war (along with three of his brothers who also played major league baseball).

No one on the West Coast escaped suspicion. The mayor of San Francisco, Angelo J. Rossi, was subpoenaed by his own chief of police and questioned about his loyalty before a state senate fact-finding committee on un-American activities. Although there was no evidence that Rossi had any Fascist connections, the committee’s accusations were among the factors that contributed to his defeat in 1943.

Joe DiMaggio and first wife, Dorothy Arnold, with his parents, Rosalie and Giuseppe. Both of DiMaggio’s parents were deemed enemy aliens during World War II.

On the East Coast, where a much larger Italian-American population had achieved substantial political power, it proved harder to isolate and target individuals. Ettore Patrizi, the editor and publisher of San Francisco’s L’Italia, had been forced to move from his home; but Generoso Pope, the publisher of New York’s pro-Fascist and more widely circulated Il Progresso, never faced any government sanctions or restrictions, no doubt because of his political clout and personal relationship with Roosevelt.

No one on the West Coast escaped suspicion. A state senate committee questioned the mayor of San Francisco, Angelo J. Rossi (standing on the right with his siblings), about his loyalty.

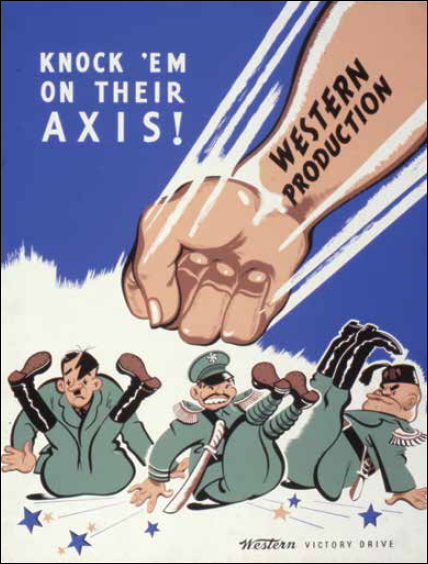

Roosevelt’s attorney general, Francis Biddle, favored selective rather than mass internment and disagreed with many of DeWitt’s plans. But he didn’t have enough clout to veto the demands of the War Department in the middle of a war. Biddle and the Justice Department knew, however, the political, social, and economic nightmare that would ensue if the East Coast Italian-American enemy aliens—over 50 percent of the Italian population in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut—had to be relocated or interned. Such a policy would affect millions of people and disrupt the nation’s economy and wartime production.

As months passed, Roosevelt recognized that the military’s plans for West Coast Italians were also out of the question. He couldn’t afford to further alienate a huge voting bloc of over five million people, with higher enlistments in the military than any other ethnic group, from the Democratic Party.

Having made Columbus Day a national holiday eight years earlier, the Roosevelt administration reached for its symbolism to announce the reversal of the government’s policy. On October 12, 1942, Attorney General Biddle, introduced by Mayor Fiorello La Guardia in Carnegie Hall, declared that Italian Americans had proved their loyalty and would no longer be under restrictions. Their enemy alien status had been lifted.

If a pattern exists to the immigrant experience—an isolated first generation dedicates itself to finding work and raising a family; a more secure second generation, recognizing the chasm between its parents and the culture, seeks to eliminate ethnic traits; and the third and fourth generations set about reclaiming ancestral roots to better define the self—World War II added a much darker dimension to this universal passage of American selfhood.

The government’s imposition of an enemy alien status went far beyond the standard humiliations of eating unrecognizable food or uttering a foreign word in place of an English one. The profound stigma of the enemy alien designation and the humiliation of restrictions and relocations kept most Italian Americans silent about the experience. When drawn out in oral histories of the time, Italian Americans typically described themselves or family members as “aliens” not “enemy aliens,” as if combining each loaded term was too much to bear—better an extraterrestrial association than that of the traitor.

With Mussolini now the enemy, being Italian-American carried a new stigma.

Joe DiMaggio’s astounding fifty-six-game hitting streak taught Americans not to take their eyes off the lithe batter at the plate or risk missing his athletic grace, yet the predicament of his parents taught Italian Americans to keep their heads down.