Tens of thousands of teenage fans swooned over Frank Sinatra.

At the end of World War II, life in America held astounding promise. As the liberator of Europe from Nazism and Fascism, the United States had won the admiration of the world; war production lifted the country from its Depression woes, boosting confidence beyond imagination. With the outlook sunny and the step light, America was eager for a new tune—sung by a slightly built, dreamy, blue-eyed singer named Frank Sinatra.

In the early 1940s, tens of thousands of teenagers ran screaming “FRANKIEE!” through Times Square when the young Sinatra played at the Paramount Theatre. Inside, they swooned with such intensity that the owner worried the building would collapse from the fervor. By mixing street swagger with stylish vocal lilts and the graceful phrasing of the bel canto tradition of Italian singing, Sinatra created an entirely new brand of urban cool.

Sinatra’s astounding musical success helped pave the way for a group of Italian-American crooners who would dominate the pop charts for the next decade. Between the years of 1947 and 1954, twenty-five Italian-American singers had major hits; and between 1956 and 1959, more Italian Americans were on the Billboard charts than ever before or since, their upbeat tempo and easygoing style perfectly matching the mood of the country. Until the Beatles redefined music in the early sixties, these soothing voices filled the airwaves.

Not all of these crooners could be recognized as Italian-American, because show business called for changing one’s name or tightening mellifluous vowels: Vic Damone was born Vito Farinola; Frankie Laine, Franceso Paolo LoVecchio; Perry Como, Pierino Como; Tony Bennett, Anthony Dominick Benedetto; Dean Martin, Dino Crocetti; Jerry Vale, Genaro Louis Vitaliano; and Connie Francis, Concetta Franconero. Each of these singers transcended their immigrant roots to become national stars with hits such as Martin’s “Volare,” Bennett’s “Because of You,” and Como’s “Prisoner of Love.”

Perry Como racked up an astounding seventy-three chart-topping songs in the 1950s. One of thirteen children born to immigrant parents in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, Como had a pleasant face, low-key manner, and cardigan sweater that defined laid-back style. Como was a barber who liked to sing and play guitar, and he would have contentedly stayed that way, but for a chance occurrence: a musician heard him sing when he was on vacation with a mutual friend and asked him to join his band. He almost quit his newfound career because he disliked the travel, but he decided to continue after he was offered a steady contract at the Copacabana nightclub. By the 1950s, his easy voice and style had garnered him a fifteen-minute television program, The Perry Como Show.

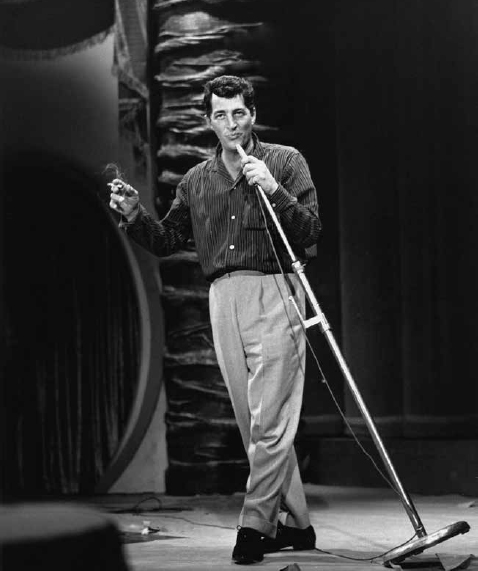

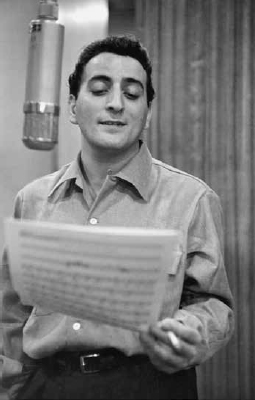

Dean Martin, born in Steubenville, Ohio, epitomized the rakish 1950s man with a cigarette in one hand and scotch on the rocks in the other. When he sang “That’s Amore,” America readily shared the love. Tony Bennett began his singing career as “Joe Bari,” thinking the two-syllable name of an Italian region might be easier on the ear than his family name. Bob Hope disliked the choice and urged him to change Benedetto to Bennett instead of Bari. Growing up in Astoria, Queens, Bennett acquired his earliest musical memories listening with his family to the great tenor Enrico Caruso and performing in front of cousins who stopped by every Sunday. After serving in World War II, he turned to the sounds of jazz and bebop—Charlie Parker, Count Basie, and Billie Holiday. Like many of the fifties crooners, Bennett’s singing idol was Frank Sinatra. As a young man, Bennett would stay all day at the Paramount Theatre to watch the singer known simply as “The Voice” perform each of his seven shows.

Dean Martin (Dino Crocetti) epitomized the rakish 1950s man.

Tony Bennett (Anthony Dominick Benedetto) dominated the pop charts in the 1950s.

Francis Albert Sinatra was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, on December 12, 1915, in a breech delivery so difficult that he was first taken for dead. The women birthing his mother were preoccupied trying to save her life, but luckily someone had the presence of mind to grab the baby and run cold tap water on his head. His shrieks announced survival. The doctor’s forceps, however, had left permanent scarring along the left side of his face, neck, and ear, prompting Sinatra to avoid being filmed from the left and to wear pancake makeup throughout his adult life to cover the disfigurement.

Sinatra spent his childhood gazing across the Hudson River and imagining himself on its glittering New York side. It wasn’t until 1939 that talent, ambition, and sheer will led him to New York City’s nightlife and fame. He took a job as a singing waiter in a New Jersey restaurant called the Rustic Cabin because it had a hookup with the radio station WNEW that broadcast in New York City. The wife of the famous bandleader and trumpet player Harry James heard Sinatra on the radio and told her husband to go see him in person. Sinatra wasn’t supposed to sing the night James came by, but good fortune befell him in the last-minute cancellation of a peer. After Harry James had heard the singer handle the challenging note variation of Cole Porter’s “Begin the Beguine,” he offered Sinatra a contract on the spot. But James’s next words fell flat: he told Sinatra to change his name to “Frankie Satin.” Sinatra famously replied that if he wanted the singer, he had to take the name.

Decades later, Sinatra told the writer Pete Hamill that the exchange with Harry James had stirred up memories of the prejudice he had encountered as a child. “Of course, it meant something to me to be the son of immigrants. How could it not? How the hell could it not? I grew up for a few years thinking I was just another American kid. Then I discovered at—what? five? six?—I discovered that some people thought I was a dago. A wop. A guinea. You know, like I didn’t have a fucking name.” Besides, Sinatra added, a name as oily as Frankie Satin would have doomed him to playing cruise ships.

The fortuitous meeting with James changed Sinatra’s life. Soon the young man was trying hard to mask his lack of education (Sinatra had dropped out of school before he reached sixteen) and his New Jersey accent. Diction lessons bolstered his confidence, and he began to create his own style. After six months with Harry James, an even bigger swing bandleader, Tommy Dorsey, offered Sinatra a contract.

In a few short years, the voice of Frank Sinatra had become a mega-phenomenon, and on October 11, 1944, the commotion around him grew so great that, as the press dubbed it, a “Columbus Day Riot” erupted. This riot, far from the earlier Columbus Day political melees when Fascists and anti-Fascists had faced off, was strictly about entertainment. Sinatra had been playing all day at the Paramount, and the overly packed theater held five thousand fans, far more than its maximum capacity of thirty-five hundred. Many of the fans wouldn’t leave after the first show, intensifying the craziness. By the end of the day, thirty thousand hysterical girls waited outside—screaming, crying, pushing—and causing a commotion over a celebrity the likes of which had never before been seen in America.

Not everyone appreciated the young man who made girls swoon, particularly servicemen. Sinatra had received a 4-F classification for a perforated eardrum, excusing him from military service. Many soldiers didn’t like this singer making love to their girlfriends with his microphone. They labeled him a draft dodger and threw tomatoes at him when they could. While few people questioned the 4-F status of famous Americans like John Wayne, many resented this son of Italian immigrants who had made it so big.

Frank Sinatra would redefine urban cool.

The draft-dodging charge hounded Sinatra throughout his career, and by the late 1940s a series of missteps seemed to doom the once invincible singer. Sinatra had a few too many run-ins with the press and even punched a newspaper columnist. He took a trip to Havana, Cuba, where he was photographed with the mobster Charlie (“Lucky”) Luciano—a decision that would forever link him with the Mafia in the public’s mind. He also began an affair with the sultry movie star Ava Gardner while he was still married to his wife, Nancy, the mother of his three children. The teenagers who once had been crazy for Sinatra had grown to be wives disgusted by infidelities that were particularly shocking for an Italian-American Catholic.

Only five foot seven and, at 130 pounds, already a slight man, Sinatra was rapidly shedding weight from the stress of the public’s ire. He even lost his voice for a while: one night in 1950 simply no sounds came out. The Italian-American singers for whom Sinatra had paved the way were now entertaining the country and topping the charts, while Sinatra was without a hit in both 1952 and 1953.

Yet, as everyone who remembers Frank Sinatra from the latter part of the twentieth century knows, the “Chairman of the Board” returned to have the world on a string. If the Sinatra story has a happy Hollywood ending, it also contains a pervasive myth that remains in the public’s imagination, no matter how many biographers have tried to debunk it. The myth centers on Sinatra’s longing for a comeback role in the movie From Here to Eternity and the belief that the Mafia told the studio it had to hire Sinatra—or else.

Sinatra was desperate to play army private Angelo Maggio for the movie version of the James Jones novel because he felt he understood, and perhaps shared a few character traits with, this troubled but charismatic Italian-American man. He even sent Harry Cohn, the founder of Columbia Pictures, who had bought the rights to the film, telegrams signed “Maggio.” But it was the glamorous A-list movie star Ava Gardner, by then his second wife, who most likely secured the role for him. She visited Harry Cohn’s wife and begged her to let Sinatra have a screen test. Gardner went even further, telling Cohn that if he agreed to the screen test, she would do a picture for him for free. Cohn eventually called Sinatra, and the screen test went so well that a part of it ended up in the final cut of the film.

Rat Pack members Sammy Davis Jr., Dean Martin, and Frank Sinatra—the ultimate bad boys having fun.

In his novel and later screenplay The Godfather, Mario Puzo decided to embellish the highly publicized story of how Sinatra got the part. One of America’s most famous movie lines—“I’m going to make him an offer he can’t refuse”—is from a scene in which Don Corleone reassures Johnny Fontane, the Sinatra-inspired character, that a movie role he desperately wants will be his. After the studio head, resembling Harry Cohn, insists the singer will never get the part, he wakes up to bloodied sheets and the severed head of his prized racehorse. The arresting psychic power of the horse’s head used as warning and revenge has been emblazoned on the American imagination, even if this narrative had no bearing on reality.

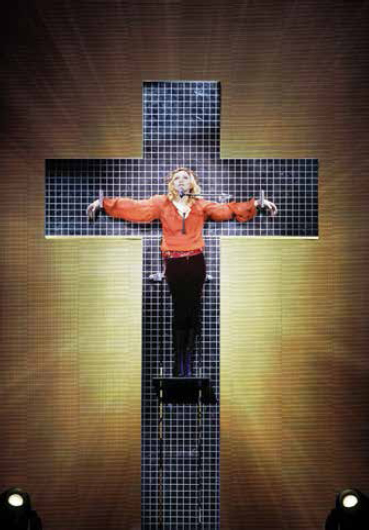

The singer Madonna performing on stage during her Confessions Tour in 2006.

Luckily, Sinatra’s instinct that Maggio was the right role for him panned out: his portrait won him an Academy Award for best supporting actor in 1953, and his comeback began. A contract with Capitol Records put his singing career back on track, and the mature voice of Frank Sinatra, combined with the lush orchestration of Nelson Riddle, created hits like “I’ve Got the World on a String.”

Over the next twenty-five years, Sinatra would record more than three hundred songs. The middle-aged Sinatra with the tilted fedora (to hide thinning hair), slightly wrinkled white shirt, and skinny tie personified an urban style that hipsters imitate today. He became the ultimate bad boy having fun, cavorting with his Rat Pack friends: Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop. The appealing and lasting cool of the Rat Pack’s Ocean’s Eleven film capers convinced Steven Soderbergh to direct a remake and two sequels in the new millennium, starring George Clooney and Brad Pitt. One hundred years after his birth, Frank Sinatra’s elegant vocals continue to be admired by superstar singers: Jay-Z declares in “Empire State of Mind” that he is the new Frank Sinatra, ready to make it anywhere. Sinatra remains the first Italian-American singer to have given millions of immigrants a taste of what it meant, with its impossible highs and feverish lows, to live the American dream.

The next time Italian-American singers became pop culture icons, two women created the phenomenon. By the late twentieth century, worldly cynicism had supplanted American promise. Third- and fourth-generation rebellion had replaced immigrant determination. Enter Madonna Louise Ciccone, born to an Italian-American father and French-Canadian mother, who in 1983 released her first album and in the following decades would sell over three hundred million—more than any other female singer.

Madonna, raised in Bay City, Michigan, by her father after his wife, the mother of six children, died young of cancer, has said that Sinatra was an important influence while she was growing up. But Madonna was referring to Nancy, Frank’s daughter, whose 1966 hit, “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’,” made a big impression on the eight-year-old Ciccone. Walking over someone with pastel-colored go-go boots—the image stuck with the future megastar Madonna, who made female power and sexuality prominent motifs in her songs and music videos.

In the 1980s, Madonna’s signature style of dressing included lacy underwear and giant crosses, turning the sacred icon of her Catholic upbringing into mass-marketed jewelry for a vast female following. The Catholic hierarchy that had once protested the blending of the sacred and the profane during religious street processions was made apoplectic by Madonna’s use of religious symbols to promote her pop music. Her videos and stage performances, beginning with the 1984 recording of “Like a Virgin,” have included burning crosses, the use of stigmata, and even a crucifixion of her on stage during the Confessions Tour in 2006. Critics called her crass and attention-getting, while fans defended Madonna as brave and boundary-breaking.

A similar desire to flaunt convention and turn Christian symbolism on its head became even more shocking in the work of Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta, known to the world as Lady Gaga (the stage name came from the song “Radio Ga Ga” by the group Queen). Madonna and Lady Gaga are frequently compared, and both are recognized more for their dance music and outré performances than their vocal range.

Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta, known to the world as Lady Gaga.

Gaga, who attended the elite all-girls school Convent of the Sacred Heart in New York, determinedly broke free of her thirteen years there. Her music video “Judas” depicts the pop star riding on the back of a motorcycle driven by a man in a crown of thorns as she looks longingly at a biker wearing the name Judas on his leather jacket. In another scene, she cavorts in a tub reminiscent of a baptismal font with both men. The music video “Alejandro” includes scenes of sadomasochistic sex juxtaposed with Gaga dressed as a nun in a latex habit sucking and swallowing rosary beads.

Since her debut single “Just Dance” in 2008, Lady Gaga has become an international superstar. Her third album, Born This Way, sold over one million copies in a week. Presenting herself as the friend and fellow traveler of outcasts, Lady Gaga has a huge following among the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community.

Both Madonna and Lady Gaga grew up surrounded by Roman Catholic imagery, and they have made religious pageantry a central element of their performances. Both are part of a cultural inheritance that has never shied away from the baroque. As far back as the sixteenth century, Italy’s popular art shocked its more subdued European neighbors: a Neapolitan painting of the Madonna depicts her with lactating breasts delivering milk to souls in purgatory. Saints like the willowy Sebastian appeared as gender ambiguous as some of Lady Gaga’s fans. Both women have changed the nature of music and stagecraft by aggressively using these symbols and flaunting their own sexuality. They have made Frank Sinatra’s bad-boy behavior and the Rat Pack serenading a woman to spend the night because “baby, it’s cold outside” seem as tame as a glass of warm milk and cookies.

Dion DiMucci helped introduce rock and roll in the 1950s, leading his doo-wop group Dion and the Belmonts and later singing solo. His chart-topping hits included “The Wanderer,” “Teenager in Love,” and “Runaround Sue.” Dion grew up in the Belmont section of the Bronx (hence the group’s name) and found his early inspiration not in Italian-American crooners, but in the blues guitar of Jimmy Reed and the country music of Hank Williams. Bruce Springsteen once remarked that Dion’s music was the bridge between Frank Sinatra and rock and roll.

Dion DiMucci helped introduce rock and roll in the 1950s, leading his doo-wop group Dion and the Belmonts and later singing solo. His chart-topping hits included “The Wanderer,” “Teenager in Love,” and “Runaround Sue.” Dion grew up in the Belmont section of the Bronx (hence the group’s name) and found his early inspiration not in Italian-American crooners, but in the blues guitar of Jimmy Reed and the country music of Hank Williams. Bruce Springsteen once remarked that Dion’s music was the bridge between Frank Sinatra and rock and roll.

Q: What was it like growing up in the Bronx in the forties and fifties?

DiMucci: It was great. All the tenement buildings were built by my relatives, and they were carving out marble for stairs. My grandmother would come down with a pot of hot water and soap and actually clean the stoops because the kids would sit on them. Everything revolved around the church. Mount Carmel Catholic Church was the hub of Little Italy in the Bronx. As a kid growing up in the forties, on those cold winter December nights, with the snow on the ground, and it’s silent and you walk into the church—there were the candles, the choir, the awe, the wonder, the majesty. It felt like you were home in the arms of God.

Q: Did your extended family live nearby?

DiMucci: I used to run out of my house to practically any apartment building and I had an aunt or an uncle who lived there with my cousins. As soon as you’d knock on the door, there’d be food on the table. I’d run over to my grandmother’s house, and she’d open the door, and she’d say, “Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, thank you for this lovely boy,” and she’d grab my cheeks and feed me oranges and provolone cheese. Oh, God, it was good. It was good.

Q: You were always very aware of being Italian?

DiMucci: My grandfather came to this country in 1907 when he was sixteen. He didn’t have any money. He educated himself. He had eight children. My mother was the oldest. My mother always said, “I left school at fourteen to work and help my family, and I was so proud when I could help them.” Today, you’d get arrested for that. My grandfather Tony would take me to a theater called Windsor in the Bronx. In the forties they had the operas there—La Boheme, La Traviata, Pagliacci. We would sit in the balcony. I’d say, “What does that all mean?” He’d explain to me the clown in Pagliacci. The clown made its way into some of my rock-and-roll songs.

Q: The Italian-American crooners of the time were on the top of the charts. But you were playing Hank Williams.

DiMucci: Yeah, I was into something totally different. I ran home from school just to catch maybe twenty minutes of the Don Larkin show that came out of Newark, New Jersey. He played country music. I wasn’t into the Italian singer.

Q: You’ve said that Hank Williams brought you beyond your neighborhood. As you grew older, did the nurturing aspect of your neighborhood feel at all suffocating?

DiMucci: I think some of my friends got threatened that my world was opening up. There was maybe a fear of the outside world—just stay close—but I was breaking out of that. That’s what rock and roll was all about: expressing your individuality and your freedom.

Q: Why do you think there were so many Italian-American singers in the fifties?

DiMucci: I think in the culture, there’s a rhythm. It’s like there’s a rhythm in the way they talk and the way they express themselves. It’s very demonstrative. I think there was a rhythm of the city, the rhythm of Italians, the church, the music. Music was part of the fabric of being Italian and part of growing up.