City Lights, cofounded by Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Peter Martin (the son of anarchist Carlo Tresca), helped establish the careers of the Beats by printing their early work.

City Lights, cofounded by Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Peter Martin (the son of anarchist Carlo Tresca), helped establish the careers of the Beats by printing their early work.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a few radical voices heralded a call about the dangers of a too complacent and self-satisfied America. In the literary world, counterculture writers riffed on paper like jazz artists improvising on stage, and on university campuses dissent movements blossomed, sending students from the ivory tower to the streets. Poet Gregory Corso and student activist Mario Savio played leading roles in these movements, and their voices against conformity and injustice recalled those of early-twentieth-century radical paesani.

Along with his pals Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William S. Burroughs, Gregory Corso formed a group of hipster poets known as the Beats, who experimented with drugs, declared free love, and decried capitalism and materialism. When Corso’s book of poetry titled Gasoline was published in 1958, Jack Kerouac described him as “a tough young kid from the Lower East Side who rose like an angel over the rooftops and sang Italian songs as sweet as Caruso and Sinatra, but in words.” Yet this sugarcoated description seemed off-note for the in-your-face Beat, who was closer in spirit to the Italian anarchist than to the crooner.

The worldview of anarchist forebears had its corollary in the Beats’ rejection of authority and search for transcendence from a tainted world. And in the lyrical symmetry of history, the son of an Italian-American anarchist made the publication of Gasoline possible. Peter Martin—who cofounded the City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco with another free-spirited half Italian, poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti—was Carlo Tresca’s son. (Martin was the progeny of an affair between Tresca and Bina Flynn, the sister of Tresca’s longtime lover, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. Elizabeth had become Tresca’s partner after the two met in Lawrence, Massachusetts, rallying striking millworkers.) City Lights helped establish the career of the Beats by printing their work under its publishing wing, City Lights Books.

Corso’s poetry was rooted in the hardship and squalor of his youth, wounds carried from parental abandonment and teenage imprisonment. Born Nunzio Corso at 190 Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village on March 26, 1930, he was the son of Italian immigrants—sixteen-year-old Michelina Colonna Corso and seventeen-year-old Fortunato Samuel Corso (known as “Sam”). Michelina left Sam when Nunzio was an infant, depositing her son on the doorsteps of Catholic Charities. The boy bounced from foundling hospital to foster homes. Sam Corso eventually remarried, but Nunzio, who later went by his confirmation name Gregory, had a difficult relationship with his father and stepmother. Forced by Sam to leave school in the sixth grade, Gregory ran away at the age of twelve, and after spending time on the streets, he was placed in a boys’ home.

At thirteen, Gregory was arrested for stealing a radio and spent five months in the notorious Manhattan prison known as the Tombs, the first stop on a horrid childhood odyssey. He was also sent to Bellevue Hospital’s psychiatric ward for three months. At seventeen, he stole a used suit, worth less than fifty dollars, to wear on a date. The crime earned him a three-year sentence at Clinton State Prison in Dannemora, New York, near the Canadian border—the same facility that had housed mafia boss Lucky Luciano in the 1940s.

Corso dedicated Gasoline to “the angels of Clinton Prison who, in my seventeenth year, handed me, from all the cells surrounding me, books of illumination.” Corso told the story, which might be one of the poet’s elaborate yarns, of Lucky Luciano donating money for a library at Clinton State after he left the facility, which provided young Gregory with the education he’d never had. The poet also liked to talk about a high-level mob figure who helped protect him in prison. (In one of Corso’s collected letters, he railed against, after seeing the movie Goodfellas, “wop mafia ignorant Ginszo pain hurt and hard-headedness, true to such false life,” adding, “Glad when I left prison I made friends with Bohemians, not hoods. Can’t bear dumb talk. Even in prison, the hoods I knew were the head guys, with the smarts.”)

From this prison library, Corso read the poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley and Arthur Rimbaud, along with Stendhal’s The Red and the Black. He devoured the poetry and prose, as well as the contents of a 1905 dictionary, and left prison knowing that he would become a poet. Shortly thereafter, Corso met Allen Ginsberg in Greenwich Village and shared with him his writing.

Corso also became friends with a poet named Violet (“Bunny”) Lang, who took him with her to Cambridge, Massachusetts. She put him up in housing for five dollars a week, but when the deal fell through, Lang approached a Harvard student named Peter Sourian and asked if he could lodge Corso in his dorm room. Sourian and his five roommates at Eliot House took Corso in, cordoning off a space in their living room with tie-dyed sheets. Corso sat in on Harvard classes, and the college boys pilfered food from the dining hall for their yearlong stowaway. Sourian, a former professor at Bard College, remembers Corso as a considerate roommate, careful not to wear out his welcome, who recited reams of Shelley’s poetry with a near-photographic memory. The Harvard students admired Corso’s verse and helped him publish his first collection, written between 1954 and 1955, The Vestal Lady on Brattle.

Corso’s poetry, which combines the dark and the sublime, can matter-of-factly describe a woman who eats children or the suicide of an unnamed girl in Greenwich Village. Yet a playful humor, surprising imagery, and gratitude toward the beauty and wonder surrounding him also suggest transcendence from a brutal world. Unlike the other Beats, all of whom were Ivy League educated, Corso had acquired his hipster lingo from genuine street credentials.

Corso joined his fellow Beats in poking fun at conformity and societal expectations, perhaps best illustrated in the often anthologized poem “Marriage.” The protagonist asks if he should get married and be good, knowing that he is the type to take a date not to the movies, but to cemeteries to tell “about werewolf bathtubs and forked clarinets.” He imagines trembling before the priest, and not knowing “what to say say Pie Glue!” (The lengthy poem so charmed actor Ethan Hawke that when he was a teenager, he memorized it to recite on dates.)

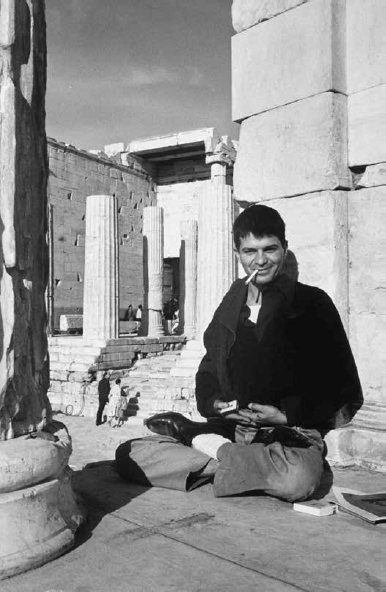

Gregory Corso seeking the Muse in Greece. Corso’s poetry combined the dark and the sublime.

After the fame of the Beat movement faded, Corso struggled to support himself, his difficulties compounded by drug and alcohol addiction. Despite his personal battles, he always remained steadfast in his vision of the poet as societal seer. In the late 1990s, documentary filmmaker Gustave Reininger was working on a film about the poet and the Beat movement. Knowing that Corso’s life had been defined by his early abandonment, Reininger hired a detective to try to track down his mother. Sam Corso had told Gregory that Michelina went back to Italy, so the filmmaker first looked for her there. But he found her instead in Trenton, New Jersey, a middle-class housewife with a family of her own. Reininger reunited mother and son, and Michelina explained that she had been badly beaten and abused by Corso’s father, who knocked out her teeth, and the scared and impoverished sixteen-year-old had fled. In 2001, Gregory Corso would succumb to prostate cancer, but the discovery closed the circle that had haunted him. One of the leaders of America’s counterculture movement finally found some personal peace discovering his Italian mamma.

“Blessed be the revolutionaries of the Spirit!” Corso wrote about those who “boot tyrannical values” without spilling blood. He was referring to the role of the poet, but surely he would have approved of the student leading a campus sit-in.

On December 2, 1964, at the University of California at Berkeley, Mario Savio took the microphone to protest the administration’s decision to suppress political activity and shut down a free-speech area on campus grounds. The twenty-one-year-old had become a known figure on campus, standing in his socks on top of police cars and addressing a student body increasingly frustrated with the actions of the administration. That day, he spoke with an originality and power to move people into action reminiscent of Arturo Giovannitti, the gifted leftist orator who had roused Lawrence millworkers in 1912 and persuaded a jury of his innocence. Savio famously proclaimed:

There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part; you can’t even passively take part. And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all.

Those words launched a thousand students to occupy Sproul Hall, Berkeley’s main administrative building, in a massive sit-in. Most of the students, including Savio, remained there until they were dragged away by police. Their actions represented the largest act of civil disobedience ever to take place at an American university. A week later, UC Berkeley president Clark Kerr gave in to the students’ demands and allowed political activity on campus.

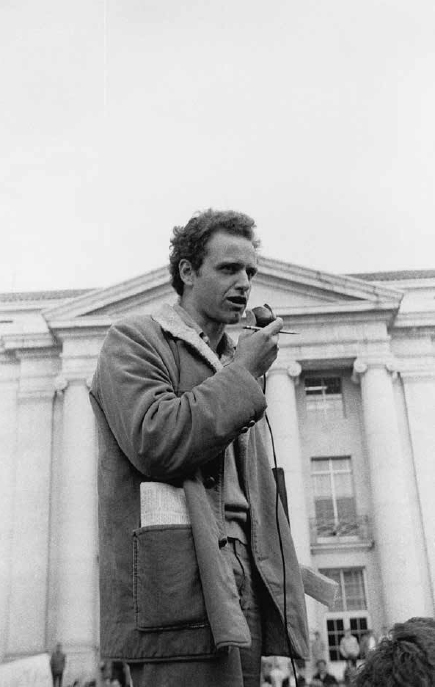

Gifted orator Mario Savio helped to start the Free Speech Movement on college campuses.

Savio, receiving much of the credit for the administration turnaround, helped create what became known as the Free Speech Movement on college campuses, which strongly influenced student activism later in the decade against the Vietnam War. His speech dazzled students and professors alike; most amazing was that Savio had spent much of his young life battling a terrible stutter.

Mario Savio came to Berkeley by way of Queens, New York, where he was raised in an immigrant working-class Italian household. Although Savio spoke Italian fluidly with his parents, Joseph and Dora, in English he struggled with a debilitating stutter. Political battles were also not new to him; he had grown up listening to heated and frequent arguments between his grandfather, a Mussolini supporter, and his father, a machine punch operator and FDR Democrat.

Until college, Savio was known as “Bob” after a priest made fun of the name Mario in class. The incident so upset his parents that they decided to call him by his middle name, Robert. Savio later observed that the episode had taught him that “to be an American” meant “to hide your Italian-ness.”

The young Savio wanted to go away to college and hoped to apply to Harvard, but his father insisted that he stay nearby. As valedictorian of his high school class, he won a full scholarship to the Roman Catholic Manhattan College in the Riverdale section of the Bronx. Traditionally, the valedictorian addresses the graduating class, but administration officials, concerned about Savio’s stutter, said he didn’t have to make a speech. Savio refused to give up this role and, after a halting start, eloquently delivered his remarks (an achievement Savio later deemed a “miracle”), criticizing American materialism and urging student involvement to better the world.

At Manhattan College, Savio was unhappy, finding the Catholic atmosphere oppressive, so he transferred to the tuition-free Queens College. Still not content, he considered dropping out of college but transferred once again, this time to Berkeley.

In California, he seemed to thrive. After his first year at Berkeley he volunteered for the Mississippi Freedom Summer campaign, where he helped register disenfranchised African Americans to vote. Savio reclaimed part of his Italian-American identity, using his birth name Mario, and began to conquer his stutter, which was still pronounced in small-group conversations but disappeared when he took the microphone.

A former altar boy, Savio considered entering the priesthood, but he became disillusioned with the faith and found salvation studying Greek history, philosophy, and literature. His embrace of, and later disillusionment with, the church was akin to Arturo Giovannitti’s experience, and their similar interest in classical studies may have helped shape the rhetoric of two formidable Italian-American orators. Both believed in equality and compassion toward the poor, fundamental tenets of the faith they abandoned; Giovannitti embraced the egalitarianism of socialism, and Savio became a voice of the New Left. But Savio rejected political labels. His biographer, Robert Cohen, calls him a reformer and a revolutionary who “wanted immediate egalitarian change, disdained compromise, loathed bureaucracy, and worked for a total transformation of race relations and university life.”

Yet Savio’s student activism came with great personal cost. UC Berkeley suspended Savio, and the hero of the Free Speech Movement was sentenced to four months in prison after a judge decided that student sit-ins were acts of trespassing and the civil disobedience posture of going limp amounted to resisting arrest. Savio eventually dropped out of the movement, believing that the glare of his media fame hurt its nonhierarchical structure. He also battled depression and panic attacks, and in the seventies he struggled to support his wife and children. The following decade, Savio earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from San Francisco State University, and he taught math and philosophy at Sonoma State University. On the twentieth anniversary of the Free Speech Movement, Savio returned to Berkeley as the keynote speaker and passionately decried the politics of Ronald Reagan and the administration’s intervention in Central America.

Mario Savio was fifty-three years old when he died from heart problems. He was fighting at the time on behalf of his working-class students against a fee hike at Sonoma State. Shortly after his death, the University of California renamed the spot at Sproul Hall where he had made his unforgettable extemporaneous speech the “Mario Savio Steps.”

FROM DIANE DI PRIMA’S RECOLLECTIONS OF MY LIFE AS A WOMAN

Diane Di Prima was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1934. A talented student, she gained admission to the selective Hunter High School—an occasion that provoked her father to remind her to never “expect too much, always remember you are Italian.” She attended Swarthmore College for two years but dropped out to move back to New York City and establish herself as a woman poet in the emerging all-male Beat movement. She coedited a literary magazine called The Floating Bear with Amiri Baraka (then known as LeRoi Jones) and was cofounder of the Poet’s Press and New York Poets Theatre. Di Prima is the author of over forty books and was named San Francisco’s poet laureate in 2009.

In the following excerpt from her memoir Recollections of My Life as a Woman, Di Prima describes how the anarchist spirit of her grandfather, Domenico, influenced her days working in the Phoenix bookstore in Greenwich Village and supporting herself as a poet. It was a time of literary repression: Allen Ginsberg’s poem “Howl” was on trial, and the works of writers such as Henry Miller and Jean Genet had been banned. Di Prima worked on a scheme with her boss, Larry Wallrich, to bring banned books to the United States.

Larry was a quiet, gentle man as I have said—and an anarchist and utter radical. With everything that word meant at the cusp of the 1960s. Political exasperation, all the frustration of the ʼ50s, looking for an outlet. And as far as I was concerned: while I held onto my healthy suspicion of all “organizations” as such, I would eagerly do whatever came to hand to help to bring down the established order. Nothing that had happened—from the times when I went with my grandfather to rallies in Bronx River Park, all the way to working here in this bookstore, with my baby beside me—had changed my point of view . . .

The Phoenix had its own underground railroad for books, its own method of importing desired but forbidden literature. Most of it was printed in France by Olympia Press, and book-like packages coming from France to the U.S. would have been suspect—likely to be examined by customs. In the system that Larry Wallrich had worked out, the books went from France to Turkey, where a friend of his lived. In Turkey, they were wrapped in small packages (about three books to a package) and stamped with the return address of an Episcopalian funeral home in Ankara. They were then duly labeled as somebody’s ashes, and sent to an address (ostensibly a relative of the deceased) in New York City. Each two- or three-book package was sent to a different address of course (Larry had plenty of friends in New York to receive them), and the mailing was spread out over a period of weeks. It seemed that no one at customs felt a strong urge to open packages of Episcopalian bones and ashes—the books got through.