New York mob boss Frank Costello wanted to convince the public that he was a legitimate businessman.

New York mob boss Frank Costello wanted to convince the public that he was a legitimate businessman.

The star power of Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Perry Como, and Tony Bennett helped associate Italian Americans with mellifluous voices, laid-back ease, and urban cool; and figures such as Gregory Corso, Diane Di Prima, and Mario Savio laid the groundwork for a growing counterculture movement. But the majority of the ethnic group was still struggling to lift itself out of its blue-collar status and battle a lingering prejudice. Making these circumstances worse, public attention focused on a nefarious connection that would plague Italian Americans for the rest of the twentieth century.

The fruits of Prohibition, that “noble experiment,” had fully ripened: former thugs plucked from the streets had turned into sophisticated criminals. These gangsters moved up in the world, not only dealing in gambling, smuggling, narcotics, and prostitution, but infiltrating legitimate businesses like the garment industry, construction, nightclubs, hotels, and liquor companies. Irish and Jewish gangsters, especially men like Benjamin (“Bugsy”) Siegel and Meyer Lansky, were part of this criminal network and invested in and later controlled multimillion-dollar casino enterprises.

The two largest crime syndicates, however, were Italian-American, based in Chicago and New York, heirs to Al Capone’s early bootlegging business and a criminal network led by East Harlem’s Frank Costello, who had emerged as one of the most powerful mob figures in the country. Costello even made the cover of Time magazine in 1949; behind an illustration of his thick-featured face poured shimmering silver slot machine coins.

In the 1940s and ’50s, many ordinary, law-abiding Italian Americans moved to the suburbs to distance themselves from urban crime and live the American dream. Preserving traditions like the Sunday afternoon family meal helped fortify them against ongoing prejudice.

In 1950, the year after Costello’s Time cover, Americans received a public civics lesson on how organized crime was carving up the nation’s coffers, siphoning an estimated $20 billion alone through illegal gambling. A freshman senator from Tennessee named Estes Kefauver, who had introduced bills to ban slot machine shipments, became the head of the Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce. Known as the Kefauver Committee, it began a fifteen-month investigation to uncover whether a national, possibly international, syndicate or “commission” controlled organized crime. Some experts disparaged Kefauver’s theory from the start, arguing that the Mafia consisted of ruthless competing groups trying to dominate these lucrative industries.

While the word mafia had arisen first during the New Orleans trial and lynchings in 1891 for the murder of police chief David Hennessy, and by the 1930s it frequently appeared in disparaging remarks about Italian Americans, this was the first time an American senator posed the question “What is the Mafia?” before a congressional committee.

The senator couldn’t have appeared more opposite from the high school dropouts he collected, questioned, and, at six feet three inches tall, towered over. Estes Kefauver was the grandson of a Baptist preacher who had grown up in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains and graduated from Yale Law School in 1927. The Esteses, his mother’s family, had settled in Tennessee during colonial times and traced their roots to Renaissance Italy. The senator’s namesake was a derivation of the noble Este lineage, which held its family seat, the Villa d’Este, in Tivoli outside of Rome.

The freshman senator from Tennessee, Estes Kefauver, led a fifteen-month investigation into organized crime.

Kefauver’s mother wrote moral counsel to her son each day—“Do good while life shall last,” her words harkened—and Estes Kefauver became a progressive southerner who supported New Deal legislation and school desegregation before the civil rights era. Kefauver had little experience in Washington when he sought the chairmanship of the investigative committee, but he had national aspirations, and the high-profile spot provided enough recognition for him to twice pursue the presidency. Although Kefauver failed to win the Democratic nomination, he was chosen to be the vice-presidential running mate for nominee Adlai Stevenson in 1956.

The Kefauver Committee traveled around the country, grilling gangsters, hoodlums, and gun molls in fourteen cities, including Philadelphia, Miami, and Los Angeles. The public learned about the close connection between bad cops and gangsters and the illegal gambling kickbacks lining the pockets of sheriffs and police. Initially, the hearings received only local coverage, but by the time the committee had concluded its investigation in New York, the bright lights of the television media illuminated the room.

With cameras ready, Kefauver brought out his biggest names: longshoreman head Anthony (“Tough Tony”) Anastasio, gambling kingpin Joe Adonis, and mob boss Frank Costello. The key moment that captivated American attention and sparked a decades-long fascination with the mob took place during Costello’s testimony. Most gangsters called before the committee used the Fifth Amendment to remain silent, but Costello decided to talk.

The televised Senate-organized crime hearings became so popular that they were shown in movie theaters.

Perhaps it was hubris, the belief he could convince Congress and the public that he was a legitimate businessman. Costello held a lifelong grudge against corrupt politicians and judges who earned the public’s respect while he was denounced for a life of crime, even after he invested in legitimate businesses. Costello did purchase real estate, nightclubs, and other legal pursuits, but his dark history stained the money backing these interests.

Americans had been exposed to mob characters in movies like Scarface and Little Caesar, but now an estimated twenty to thirty million viewers were watching real-life gangsters on television at home. Before the cameras rolled, Costello complained to the senators that the bright lights bothered him. As a compromise, the committee told the media that they could only film Costello’s hands. Although the director of NBC television news protested the restriction on behalf of all the broadcasters, the committee’s decision proved riveting. Costello’s hands were the sole image on the black-and-white screen, offering a cinematic angle as artfully composed as one by Martin Scorsese.

“Costello turned his automatic pencil a thousand times,” the Chicago Tribune reported. “He crumpled papers, he fiddled with book matches, he shuffled income tax returns, he clasped his hands tightly, he unclasped them, he crushed papers, he twisted fingers, he held one hand up to his head, he hung an arm over a chair, he tried a dozen positions, each one reflecting his tension more vividly than the masked face of a gambler could have done.”

“Women by the thousands deserted their household duties, afternoon bridge, and canasta for the second day to eavesdrop on the big show,” the story continued. “There’ll be more watching today. The women may not even get their dishes done.”

After the gangster Frank Costello complained that the camera lights bothered him, the Kefauver Committee agreed to film only his hands. The committee’s decision proved cinematically riveting.

Costello became so frustrated during his testimony that he stormed out on the third day, and though he finally returned, this act of contempt, along with tax evasion, would send him to prison later in the decade. The New York hearings provided the prime-time climax to the committee’s fifteen months on the road, during which over six hundred witnesses had been interviewed and America had become acquainted with men called “Greasy Thumb” and “Trigger Mike.”

Despite all of its efforts and over ten thousand pages of testimony, the Kefauver Committee never found substantial evidence that a national syndicate existed. But it exposed millions of Americans to some big-time criminals. The committee’s investigation also led to deportations and the creation of a rackets squad in the IRS that convicted nearly nine hundred gangsters. Illuminating Tammany Hall’s close connection with Costello and other underworld figures, the hearings ultimately weakened the political machine that had regained power after the end of La Guardia’s tenure in New York.

Estes Kefauver died of a heart attack in August 1963, one month shy of the opportunity to see the fruition of his efforts to expose the inner workings of organized crime, which by then was taking in about $40 billion a year. A new Senate investigation began that September, backed by the power and influence of Bobby Kennedy as the nation’s attorney general. This time the committee had an inside informer, the first willing to break the honored code of Mafia silence known as omertà.

His name was Joseph Valachi, a five-foot-three convicted murderer, narcotics dealer, and low-level mobster who decided to talk while serving a life sentence. Fearing that a $100,000 price tag had been put on his head, he badly needed government protection. While in prison, Valachi murdered with a metal pipe a fellow inmate who he believed was out to kill him, but he got the wrong guy. He arrived before Congress chain-smoking and disguised from his pursuers with brightly dyed red hair. Valachi was the first man to offer another name for the Mafia: La Cosa Nostra (“Our Thing”).

Today, mob experts believe that Valachi was too low in the organization’s food chain to know as much as he claimed and that he was being used by the feds to present information they had already obtained from prior informants. But his stories riveted a public that, for thirteen years since Costello’s flailing hands, had not seen this kind of a show.

Valachi described a secret initiation ritual that began by repeating in Sicilian dialect an oath to live and die “by the gun and knife.” The initiate is told to toss a burning paper from hand to hand and say, “This is the way I burn if I expose this organization.” Next came the prick of the finger drawing blood as a sign of brotherhood and absolute loyalty. Each inductee was designated a “godfather” to initiate the oath with the finger prick.

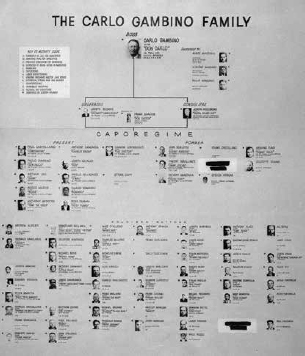

Most important, Valachi revealed how five “families” ruled this murderous organization. A “boss” headed the family, followed by an underboss, counselor (consigliere), captain, and finally soldiers. The Mafia had cleverly used the cohesiveness of the Italian family—the culture’s bedrock value—to create the loyalty and tight structure necessary to dominate organized crime in America. Valachi also named heads of the five leading families at the time: Vito Genovese, Carlo Gambino, Giuseppe Magliocco (Joseph Colombo later took his place), Joseph Bonanno, and Gaetano Lucchese.

The grudge-holding Valachi proved an even better show than the Kefauver witnesses, offering salacious details and turning illiterate bit players like himself into major criminals on a national stage. His tantalizing testimony riveted the American public: the Judas-like kiss on the cheek signaling one’s impending death; the godfather to whom one owed unquestioning loyalty; the violin case hiding a machine gun; the memorable line, “Once you’re in you can’t get out.” As a reporter covering the hearings presciently noted, “A writer of crime fiction would have gathered plenty of material in listening to Valachi.”

The Senate committee illustrated how five “families” ruled this murderous organization.

While the country’s eyes were glued to Valachi’s talk of blood oaths and Sicilian bonds, a daughter of Italian immigrants was challenging both the thugs controlling her neighborhood and an all-powerful Mayor Richard J. Daley’s plans to demolish Chicago’s Little Italy. This story of quiet heroism, however, fell outside the spotlight of a national media obsessed with Italian-American mobsters.

Florence Scala (née Giovangelo) grew up at 1030 West Taylor Street in the Near West Side, where her family lived above their father’s first-floor tailor and dry-cleaning shop. Hull House, the famed settlement founded by reformer Jane Addams, stood nearby, and a teacher suggested that Florence’s mother take her there—a decision that helped change Scala’s life. She told the oral historian Studs Terkel, “The neighborhood was dominated by gangsters and hoodlums. They were men from the old country, who lorded it over the people in the area . . . Hull House gave you a little insight into another world. There was something else to life besides sewing and pressing.”

Jane Addams’s nephew introduced Scala to the idea of city planning. She enrolled in continuing-education classes at the University of Chicago and began working with the Near West Side Planning Board. The neighborhood remained a pocket of urban blight, but Scala was hopeful that newly targeted urban renewal money from the federal government could transform the area.

These aspirations came to an abrupt halt in 1961 when Daley announced his decision to tear down large parts of the neighborhood to house a campus of the University of Illinois. Daley doomed a beloved Catholic church and Hull House to the wrecking ball, along with eight hundred houses and two hundred businesses. Scala led the opposition to the mayor’s heavy-handed plan, organizing, picketing, and occupying City Hall with fellow Italian-American women during a two-hundred-person sit-in composed mostly of mothers trying to protect their family homes and shouting furiously that the rich always take away from the poor. After someone mysteriously bombed Scala’s home with dynamite, she and her husband Charles moved into an apartment at Hull House.

Scala took the case against Mayor Daley to the Supreme Court but lost—a decision that condemned one of Chicago’s oldest ethnic enclaves. Her sole success was preserving the original Hull House building. The family home at 1030 West Taylor Street had never been slotted for demolition—her advocacy had always been on behalf of the neighborhood—and she and Charles moved back, remaining there for the rest of their lives.

Florence Scala (left), picketing to save her Italian-American neighborhood from Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley’s wrecking ball.

In 1964, still fresh from the wounds of the destruction, Scala ran for First Ward alderman, declaring that she was determined to “mark the beginning of the end for the hoodlums who have dominated the ward since the beginning of this century.” Despite support from young people and independents, she was badly defeated. Florence Scala, who died in 2007, has been described as a “Rosa Parks of the Italian-American neighborhood.” Studs Terkel called her “my heroine,” who “tried with intelligence and courage to save the soul of our city. She represented to me all that Chicago could have been.”