CHAPTER 1

In the Box-room

‘I’m bored!’ said Ned.

He stood with his hands in his pockets and his lower lip stuck out, staring out of the window of his grandmother’s sitting-room.

Outside it was blowing half a gale, the heavens were emptying and the raindrops chased one another endlessly down the window-pane.

‘When I was your age,’ said his grandmother, ‘we made our own amusements. Haven’t you got a book to read?’

‘Yes, but it’s boring.’

‘Well, draw or do a jigsaw or a crossword puzzle or play a game of Patience. Which is something you could do with, Ned. You seem to expect to be entertained all the time. If you go on saying you’re bored, I shall find you some work to do. Like cleaning the silver. Except that you’d make an awful mess of it.’

Ned’s grandmother put down her embroidery, took off her spectacles and stood up.

‘Talking of awful messes,’ she said, ‘has just given me a brilliant idea. It’s something I’ve been meaning to do for ages, but I’ve funked it. A filthy day like this would be just the time to tackle it, specially with a big strong nine-year-old boy to help me.’

Ned brightened at being called big and strong, but he was suspicious. Whatever it was sounded like hard work.

‘I shouldn’t bother, Gran,’ he said hastily. ‘I’ll be all right. I’ll find something to do.’

‘Too right you will, pet,’ said his grandmother. ‘We are going to clear out the box-room.’

‘The box-room?’ said Ned. ‘Whatever’s that? I didn’t know you had one.’

‘Come on. I’ll show you.’

‘But this is the attic,’ said Ned, when they had climbed three flights of stairs to the top of the old house. ‘Oh Gran, we’re never going to clear out all this stuff?’

He looked around at the assortment of junk that stood on the boarded floor of the long narrow room directly below the roof. There were trunks and suitcases and hat-boxes, bags of old golf-clubs, some cases of stuffed birds, a number of framed paintings leaning against the wall, piles of old books, offcuts of carpeting and all manner of other things that Gran kept ‘because they might come in useful one day’. Standing proudly above the rest was a dapple-grey rocking-horse with flaring salmon-pink nostrils. A younger Ned had often ridden it when nosing about in the attic, and now he sat on its wooden saddle, his feet touching the ground, and urged it into squeaky action.

‘I didn’t know you called this the box-room,’ he said.

‘I don’t,’ said his grandmother.

She picked her way towards the far end of the room, where there stood a tall, folding tapestry screen.

‘Give me a hand to move this, can you, pet?’ she said, and when they had done so, Ned could see that what had always seemed to be the end wall of the attic, was not. There was a little door in it, no more than four feet high, and when his grandmother had opened it and switched on a light within, Ned could see that there was yet another room beyond. It was filled from floor to ceiling with cardboard boxes.

There were hundreds of them, of all shapes and sizes, from boxes small enough to have held an alarm clock or a coffee mug to great cartons you could have put a week’s supermarket.shopping.in.

‘Gran!’ cried Ned. ‘Whatever have you kept all these for?’

His grandmother grinned a bit sheepishly.

‘You never know when you might need a box for something or other,’ she said. ‘But I have been intending to clear the place out, honestly I have, Ned. For about forty years. I keep saying to myself, I must do it before they put me in my own one.’

‘Own what?’

‘Box.’

‘I don’t understand.’

‘Wooden box – coffin – you know.’

‘Oh Gran!’ said Ned.

‘Comes to us all,’ said his grandmother. ‘But not for a while yet, let’s hope. Come on, let’s start,’ and she bent to get through the low doorway. ‘No,’ she said, ‘on second thoughts, that’s not a good idea. I may not be the tallest woman in the world, but ducking under there isn’t going to do my back any good at all. Would you mind passing them out to me?’

‘Course I will,’ said Ned.

He looked round the attic.

‘Tell you what, Gran,’ he said. ‘If you open that window there, you can chuck them straight out as I give them to you, and they’ll land on the lawn below. Save us carrying them all downstairs. Then we can have a bonfire.’

‘But they’ll get wet outside.’

‘No they won’t. Look, the rain’s nearly stopped, Gran.’

So, for the best part of half an hour, Ned carried out box after box and passed them to his grandmother, and she threw them out of the window with loud cries of ‘Heads below!’ and ‘Timber!’ and ‘Bombs gone!’ until at last the box-room was almost empty.

‘Nearly done, Gran,’ Ned said.

‘How many more?’

‘About a dozen.’

‘You can chuck those out while I’m going downstairs,’ said his grandmother. ‘And then shut the window and turn the lights off, will you?’

When the final box had gone spinning down, Ned took a last look through the box-room’s little door. Then he saw that there was still one left, a shoebox tucked right under the angle that the roof made with the edge of the floor. He pulled it out and saw that, unlike the rest, it was neatly tied up with string. Picked up, it felt too heavy for an empty shoebox. Ned undid the string and took off the lid.

Inside there lay a doll.

She was perhaps eighteen inches from head to toe, and dressed in an ankle-length gown nipped at the waist by a sash of pink silk. The gown was apple-green and patterned with circlets of flowers, little white flowers with yellow centres, and round one arm the doll wore a black velvet band. Her shoes were pink to match the sash, and on her arms were elbow-length white gloves.

Her hair was black and flowing, and her face was rosy-cheeked and rosebud-mouthed like all her kind, the closed eyes fringed with long dark lashes. As Ned stared at the doll, he heard his grandmother’s voice from the lawn below, calling him to hurry, they must carry all the boxes down to the orchard and set them alight before the rain should start again.

Quickly Ned put the lid back on and, opening an old trunk that stood near by, popped the shoebox in. He closed the window, turned off the lights and ran downstairs.

Later that day, when the contents of the box-room had been reduced to a pile of ashes in the orchard, Ned climbed back up to the attic.

He took the shoebox from its hiding-place, opened it and lifted out the doll. He had said nothing to his grandmother about finding it, he didn’t quite know why. Dolls were girls’ things, of course, but it wasn’t that.

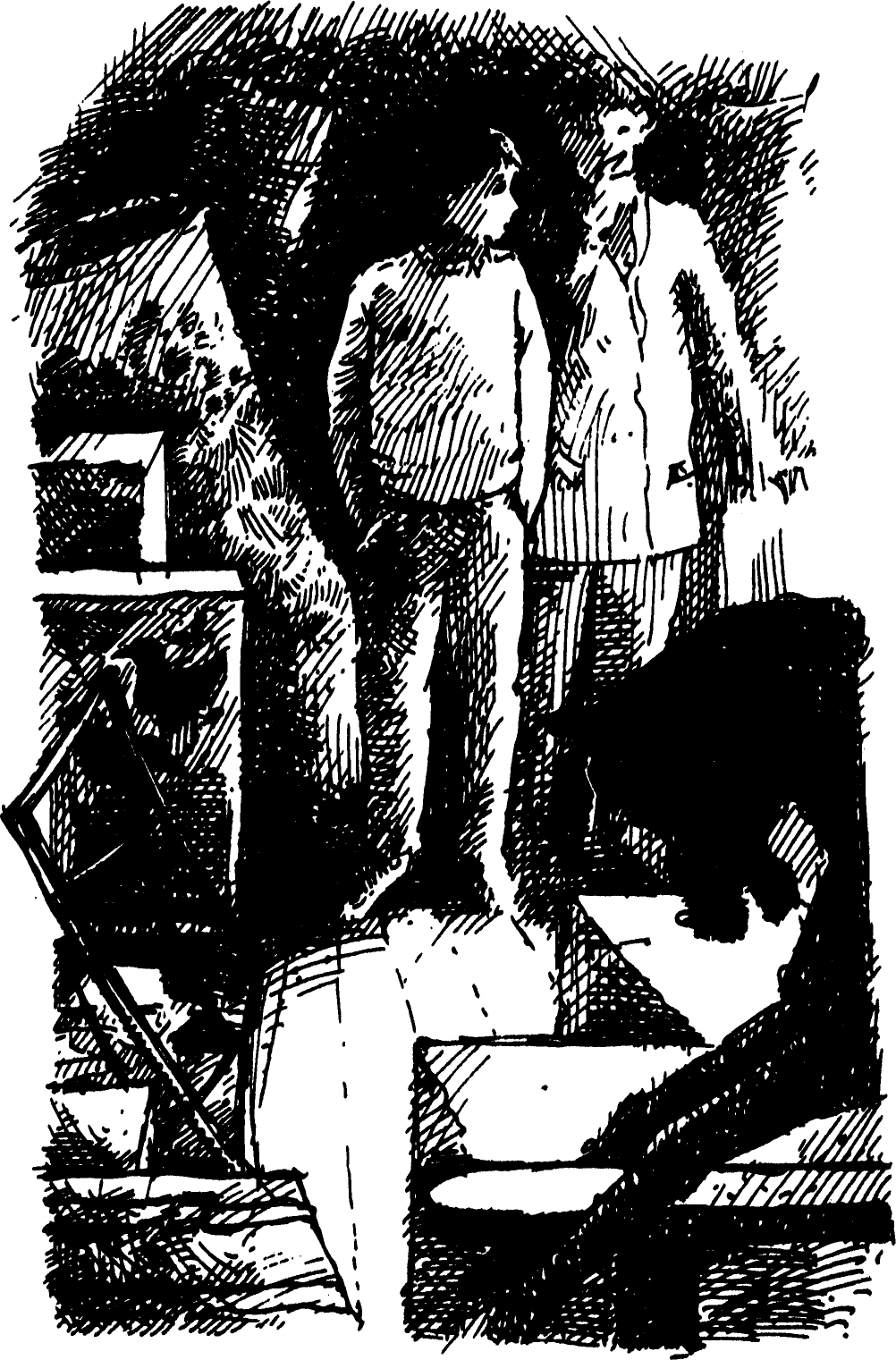

As he stood the black-haired doll upright on top of the trunk, its eyelids slid back, and it gazed at him out of its two large round baby-blue eyes. Then it spoke.

‘Who in the world are you?’ said the doll.

Ned gulped. The hairs on the back of his neck stood up and his legs felt funny.

‘My name’s Ned,’ he said in a croaky voice.

‘Why are you wearing fancy dress?’ said the doll.

Ned glanced down at his jersey and T-shirt and jeans and trainers, and could think of nothing to say but, ‘I’m not.’

‘And where is Victoria?’ asked the doll. ‘I may have overslept a little, I grant you, but I had expected to see Victoria, as usual.’

‘Who’s Victoria?’ asked Ned.

‘My dollmother.’

‘Dollmother?’

‘The little girl who looks after me. She is younger than you, I should say. How old are you, by the bye?’

‘Nine.’

‘Ah, Victoria is but five. Now, let me see, the last thing I remember her saying was that the dear Queen is dead. Is that not sad?’

‘The Queen’s not dead,’ said Ned. ‘If she was, Charles would be King.’

‘Charles?’ said the doll. ‘History, I can see, is not your strong subject. Charles the Second died more than two hundred years ago. You’ll be telling me next that the Queen’s name is Elizabeth.’

‘Well, it is.’

‘Foolish boy! Why, my dollmother is named after our great Queen-Empress. For sixty-four years Queen Victoria has reigned over us, and now she is gone. Nothing will ever be the same again.’

Nothing ever will be, thought Ned. Then he said, ‘What year do you think . . . I mean, what year is it – now?’

‘Do you know nothing, Master Ned?’ said the doll. ‘Why, it is 1901, of course.’

‘Oh,’ said Ned.

He forced himself to look into the wide blue eyes. It was unnerving to be addressed without facial movement of any kind.

He summoned up his courage and said, very politely, ‘I’m awfully sorry, but I’m afraid I don’t know what you are called.’

‘Strange,’ said the doll. ‘One would have expected Victoria to have told you.’

She said nothing further but continued to stare expressionlessly until at last, in desperation, Ned said, ‘What are you called?’

‘My name,’ said the doll, ‘is Lady Daisy Chain.’

‘Oh,’ said Ned.

Despite himself, he took hold of the doll’s white-gloved right hand to shake it, and as he pulled, the arm, its upper part encircled by the black band of mourning for the late great Queen, moved stiffly forward on its shoulder-joint.

‘How do you do?’ he said.