When young, I did not dedicate books. Dedications seemed overblown and showy. It is too late to begin; but if this book carried a dedication, it would be to the memory of Nagai Kafū.

Though he was not such a good novelist, he has come to seem better and better at what he was good at. He was his best in brief lyrical passages and not in sustained narrative and dramatic ones. He is the novelist whose views of the world’s most consistently interesting city accord most closely with my own. He has been my guide and companion as I have explored and dreamed and meditated upon the city.

I do not share his yearning for Edo, the city when it was still the seat of the Tokugawa shoguns and before it became the Eastern Capital. The Tokugawa Period is somehow dark and menacing. Too many gifted people were squelched, and, whether gifted or not, I always have the feeling about Edo that, had I been there, I would have been among the squelched ones.

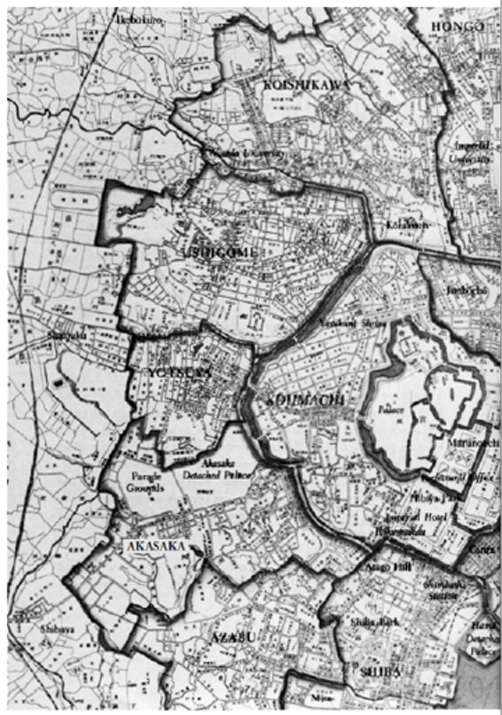

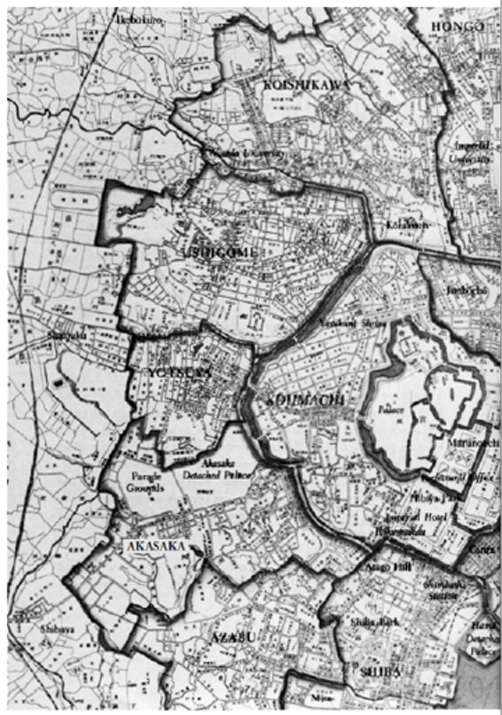

I share Kafū’s affection for the part of the city which had its best day then. The twilight of that day lasted through the succeeding Meiji reign and down to the great earthquake. It is the Shitamachi, the plebeian flatlands, which I here call the Low City. Meiji was when the changes that made Japan modern and economically miraculous were beginning. Yet the Low City had not lost its claim to the cultural hegemony which it had clearly possessed under the Tokugawa.

Many exciting things have occurred in the six decades since the earthquake, which is slightly farther from the present than from the beginning of Meiji. Another book asks to be written, about those decades and especially the ones since the surrender. Perhaps it will be written, but it would have to be mostly about the other half (these days considerably more than half), the hilly High City, the Yamanote. That is where the artist and the intellectual, and to an increasing extent the manager and the magnate, have been. If there is less in this book about the High City than the Low City, it is because one is not drawn equally to everything in a huge and complex city, and a book whose beginnings lie in personal experience does have a way of turning to what interests and pleases.

Kafū was an elegist, mourning the death of Edo and lamenting the emergence of modern Tokyo. With such a guide and companion, an elegiac tone is bound to emerge from time to time. The departure of the old and the emergence of the new are inextricably entwined, of course. Yet, because the story of what happened to Edo is so much the story of the Low City, matters in which it was not interested do not figure much. It was not an intellectual sort of place, nor was it strongly political. Another consideration has urged the elimination of political and intellectual matters: the fact that Tokyo became the capital of Japan in 1868. A distinction may be made between what occurred in the city because it was the capital, and what occurred because it was a city.

So this book contains little political and intellectual history, and not much more literary and economic history. The major exception in literary matters is the drama, the great love of the Edo townsman. The story of what happened to Kabuki is central to the story of the city, and not that of the capital. The endeavor to describe a changing city as if it were an organism is perhaps not realistic, since cities change in all ways and directions, as organisms and specific institutions do not. The subject here is the changing city all the same, the legacy of Edo and what happened to it. To a much smaller degree is it the story of currents that have flowed in upon the city because it was the capital.

Japanese practice has been followed in the rendition of personal names. The family name comes before the given name. When a single element is used, it is the family name if there is no elegant pen-name (distinguished in principle from a prosy one like Mishima Yukio), and the pen-name when there is one. Hence Kafū and Shigure, both of them pen-names; but Tanizaki, Kubota, and Shibusawa, all of them family names.

The staff of the Tokyo Metropolitan Archives was very kind in helping assemble illustrations. The prints, woodcut and lithograph, are from Professor Donald Keene’s collection and my own, except as noted in the captions. I am also in debt to the Tokyo Central Library and the Toyo Keizai Shimpō. Mr. Fukuda Hiroshi was very helpful in photographing photographs that could not be taken across the Pacific for reproduction.

The notes are minimal, limited for the most part to the sources of direct quotations. A very important source, acknowledged only once in the notes, is the huge work called A History of the Tokyo Century (although it begins with the beginnings of Edo), published by the municipal government in the early 1970s, with a supplemental chronology published in 1980. Huge it certainly is, six volumes (without the chronology), each of them some fifteen hundred pages long. Uneven it is as well, and indispensable.

Guidebooks, four of them acknowledged in the notes, were very useful, the two-volume guide published by the city in 1907 especially so. Then there were ward histories, none of them acknowledged, because I have made no direct quotation from them. The Japanese are energetic and accomplished local historians, as much so as the British. Their volumes pour forth in bewildering numbers, those Japanese equivalents of the “admirable history of southeast Berks” one is always seeing reviewed in the Times Literary Supplement. Every ward has at least one history. Some are better than others, not because some are especially unreliable, but because some are better organized and less given to axegrinding.

I do not pretend to have been through them all, but none that I have looked at has been valueless.

The most important source is Nagai Kafū. To him belongs the final acknowledgment, as would belong the dedication if there were one.

E.S.

April, 1982