CIVILIZATION AND ENLIGHTENMENT

The fifteenth and last shogun, no longer shogun, returned to Edo early in 1868.

Efforts to “punish” the rebellious southwestern clans had ended most ingloriously. The Tokugawa regime did not have the resources for further punitive expeditions. The southwestern clans already had the beginnings of a modern conscript army, while the Tokugawa forces were badly supplied and perhaps not very militant, having had too much peace and fun in Edo over the centuries. Seeing the hopelessness of his cause, the shogun resigned early in 1868 (by the solar calendar; it was late 1867 by the old lunar calendar). He himself remained high in the esteem of the city. Late in Meiji, when his long exile in Shizuoka was at an end, he would be invited to write “Nihombashi” for that most symbolic of bridges. Subsequently carved in stone, the inscription survived both earthquake and war. The widow of his predecessor was to become the object of a romantic cult. A royal princess married for political reasons, she refused to leave Edo during the final upheaval.

Politically inspired violence persuaded retainers of the shogunate to flee Edo. The provincial aristocracy had already fled. Its mansions were burned, dismantled, and left to decay. Common criminals took advantage of the political violence to commit violence of their own. The city locked itself in after dark, and large sections of the High City and the regions near the castle were unsafe even in the daytime.

The lower classes stayed on, having nowhere to go, and—as their economy had been based on serving the now-dispersed bureaucracy—little to do either. The population fell to perhaps half a million immediately after the Restoration. The townsmen could scarcely know the attitude of the new authorities toward the foreign barbarians and intercourse with barbarian lands. Yokohama was the most convenient port for trading with America, the country that had started it all, but if the new regime did not propose to be cosmopolitan, then placing the capital in some place remote from Yokohama would be an act of symbolic importance. Some did indeed advocate making Osaka the capital, or having Osaka and Edo as joint capitals.

Even when, in 1868, Edo became Tokyo, “the Eastern Capital,” the issue was not finally resolved. By a manipulation of words for which a large Chinese vocabulary makes the modern Japanese language well suited, a capital was “established” in Edo, or Tokyo. The capital was not, however, “moved” from Kyoto. So Kyoto, which means “capital,” could go on performing a role it was long accustomed to, that of vestigial or ceremonial capital. The Meiji emperor seems to have gone on thinking of Kyoto as his city; his grave lies within the Kyoto city limits.

Some scholars have argued that the name of the city was not changed to Tokyo at all. The argument seems extreme, but the complexities of the language make it possible. The crucial rescript, issued in 1868, says, insofar as precise translation is possible: “Edo is the great bastion of the east country. Upon it converge the crowds, and from it one can personally oversee affairs of state. Accordingly the place known as Edo will henceforth be Tokyo.”

This could mean that Edo is still Edo, but that it is now also “the eastern capital,” or, perhaps, “the eastern metropolitan center.” Another linguistic curiosity made it possible to pronounce the new designation, whether precisely the same thing as a new name or not, in two ways: “Tokei” or “Tokyo.” Both pronunciations were current in early Meiji. W. S. Griffis’s guide to the city, published in 1874, informs us that only foreigners still called the city Edo.

The townsmen who stayed on could not know that the emperor would come to live among them in Tokyo, or Tokei. The economic life of the city was at a standstill, and its pleasures virtually so. The theaters closed early in 1868. Few came asking for the services of the Yoshiwara. Forces of the Restoration were advancing upon the city. Restoration was in fact revolution, and it remained to be seen what revolution would do to the seat of the old regime. The city had helped very little in making this new world, and the advancing imperial forces knew that the city had no high opinion of their tastes and manners. Gloom and apprehension prevailed.

The city waited, and the Meiji armies approached from the west. One of the songs to which they advanced would be made by Gilbert and Sullivan into the song of the Mikado’s troops. It was written during the march on Edo, the melody by Omura Masujirō, organizer of the Meiji armies. The march was halted short of the Hakone mountains for conferences in Shizuoka and in Edo. It was agreed that the castle would not be defended. The last shogun left the city late in the spring of 1868, and the transfer of city and castle was accomplished, bloodlessly, in the next few days. Advance parties of the revolutionary forces were already at Shinagawa and Itabashi, the first stages from Nihombashi on the coastal and inland roads to Kyoto.

Resistance continued in the city and in the northern provinces. Though most of the Tokugawa forces scattered through the city surrendered, one band took up positions at Ueno, whence it sent forth patrols as if it were still in charge of the city. The heights above Shitaya, now Ueno Park, were occupied by the great Kan-eiji, one of the Tokugawa mortuary temples, behind which lay the tombs of six shoguns. The holdouts controlled the person of the Kan-eiji abbot, a royal prince, and it may have been for this reason that the victors hesitated to attack.

In mid-May by the lunar calendar, on the Fourth of July by the solar, they finally did attack. From early morning, artillery fire fell upon Ueno from the Hongō rise, across a valley to the west. It was only late in the afternoon that the south defenses were breached, at the “Black Gate,” near the main entrance to the modern Ueno Park, after a fierce battle. Perhaps three hundred people had been killed, twice as many among the defenders as among the attackers. Much of the shelling seems to have fallen short, setting fires. Most of the Kan-eiji was destroyed, and upwards of a thousand houses burned in the regions between Ueno and the artillery emplacements. The abbot fled in disguise, and presently left the city by boat.

* * *

If we may leave aside linguistic niceties and say that Edo was now Tokyo and the capital of Japan, it was different from the earlier capitals, Nara and Kyoto. It was already a large city with a proud history. Edo as the shogun’s seat may have been an early instance of a fabricated capital or seat of power, but it had both Chinese and Japanese forebears. Nara and Kyoto had been built upon rural land to become capitals; there had been no urban class on hand to wish that the government had not come. So it had been with Edo when it first became the shogun’s seat, but when it became the emperor’s capital there were the centuries of Edo to look back upon. The proper son of Edo had acquired status by virtue of his nearness to Lord Tokugawa, and when he had the resources with which to pursue good taste, he could congratulate himself that he did it impeccably. Now came these swarms of bumpkins, not at all delicate in their understanding of Edo manners.

Destroyed, my city, by the rustic warrior.

No shadow left of Edo as it was.

This is Tanizaki Junichirō, speaking, much later, for the son of Edo. It is an exaggeration, of course, but many an Edo townsman would have echoed him.

The emperor departed Kyoto in the autumn of 1868. He reached the Shinagawa post station, just south of the city, after a journey of some three weeks, and entered the castle on the morning of November 26. Townsmen turned out in huge numbers, but the reception was reverent rather than boisterous; utter silence prevailed. By way of precaution against the city’s most familiar disaster, businesses requiring fires were ordered to take a holiday. Then the city started coming back to life. Despite its affection for Lord Tokugawa, it was happy to drink a royal cup. Holidays were decreed in December (the merchant class of Edo had allowed itself scarcely any holidays); two thousand five hundred sixty-three casks of royal sake were distributed through the city, and emptied.

The emperor returned to Kyoto early in 1869, after the pacification of the northern provinces. He was back in Tokyo in the spring, at which time his permanent residence may be said to have begun. He did not announce that he was leaving Kyoto permanently, and the old capital went on expecting him back. It was not until 1871 that the last court offices were removed from Kyoto, and most of the court aristocracy settled in Tokyo. Edo castle became what it is today, the royal palace, and Tokyo the political center of the country. Until 1923 there was scarcely a suggestion that matters should be otherwise.

The outer gates to the palace were dismantled by 1872, it having early been decided that the castle ramparts were exaggerated, and that the emperor did not need such ostentatious defenses. Several inner gates, though not the innermost, were released from palace jurisdiction, but not immediately dismantled. The stones from two of the castle guard points were used to build bridges, which the new regime favored, as the old had not.

Initial policy towards the city was cautious, not to say confused. In effect the Edo government was perpetuated, with a different terminology.

The north and south magistrates, both with offices in the flatlands east of the castle, were renamed “courts,” and, as under the Tokugawa, charged with governing the city in alternation.

A “red line” drawn in 1869 defined the city proper. It followed generally the line that had marked the jurisdiction of the Tokugawa magistrates. A few months later the area within the red line was divided into six wards. The expression “Tokyo Prefecture,” meaning the city and larger surrounding jurisdiction, had first been used in 1868. In 1871 the prefecture was divided into eleven wards, the six wards of the inner city remaining as before. In 1878 the six were divided into fifteen, covering an area somewhat smaller than the six inner wards of the city today and the two wards immediately east of the Sumida. There were minor revisions of the city limits from time to time, and in 1920 there was a fairly major one, when a part of the Shinjuku district on the west (not including the station or the most prosperous part of Shinjuku today) was brought into Yotsuya Ward. The fifteen wards remained unchanged, except in these matters of detail, until after the Second World War, and it was only in 1932 that the city limits were expanded to include thirty-five wards, covering generally the eleven wards, or the Tokyo Prefecture, of 1872. The red line of early Meiji takes some curious turns, jogging northwards above Asakusa, for instance, to include the Yoshiwara, and showing in graphic fashion how near the Yoshiwara was, and Asakusa as well, to open paddy land. The Tokyo Prefecture of early Meiji was not as large as the prefecture of today, and the prefecture has never been as large as the old Musashi Province in which Edo was situated. The Tama district, generally the upper valley of the Tama River, which in its lower reaches was and is the boundary between Tokyo and Kanagawa prefectures, was transferred to Kanagawa Prefecture in 1871. Because it was the chief source of the Tokyo water supply and an important source of building materials as well, there was earnest campaigning by successive governors to have it back. In 1893 it was returned, and so the area of the prefecture was tripled. The Izu Islands had been transferred from Shizuoka Prefecture in 1878 and the Ogasawara or Bonin Islands from the Ministry of the Interior in 1880. The Iwo Islands were added to the Ogasawaras in 1891, and so, with the return of the Tama district two years later, the boundaries of the prefecture were set as they remain today. Remote though they are, the Bonin and Iwo Islands, except when under American jurisdiction, have continued to be a part of Tokyo. It is therefore not completely accurate to say that Okinawa was the only prefecture invaded during the Second World War.

A still remoter region, the Nemuro district of Hokkaido, was for a time in early Meiji a part of Tokyo Prefecture. The economy of the city was still in a precarious state, because it had not yet been favored with the equivalent of the huge Tokugawa bureaucracy, and the hope was that these jurisdictional arrangements would help in relocating the poor.

Tokyo Prefecture was one of three fu, which might be rendered “metropolitan prefecture.” The other two were Osaka and Kyoto. Local autonomy was more closely circumscribed in the three than in other prefectures. They had their first mayors in 1898, almost a decade later than other cities. Osaka and Kyoto have continued to be fu, and to have mayors as well as governors. Tokyo became a to, or “capital district,” during the Second World War, the only one in the land. Today it is the only city, town, or village in the land that does not have a mayor.

On September 30, 1898, the law giving special treatment to the three large cities was repealed, and so October 1 is observed in Tokyo as Citizens’ Day, the anniversary of the day on which it too was permitted a mayor. He was chosen through a city council voted into office by a very small electorate. The council named three candidates, of whom one was appointed mayor by imperial rescript, upon the recommendation of the Ministry of the Interior. It became accepted practice for the candidate with the largest support in the council to be named mayor. The first mayor was a councilman from Kanda Ward, in the Low City. Tokyo has had at least two very famous mayors, Ozaki Yukio, who lived almost a century and was a stalwart defender of parliamentary democracy in difficult times, and Gotō Shimpei, known as “the mayor with the big kerchief,” an expression suggesting grand and all-encompassing plans. Though it cannot be said that Gotō’s big kerchief came to much of anything, he is credited by students of the subject with having done more than any other mayor to give the city a sense of its right to autonomy. He resigned a few weeks before the great earthquake to take charge of difficult negotiations with revolutionary Russia, but his effectiveness had already been reduced considerably by the assassination in 1921 of Hara Takeshi, the prime minister, to whom he was close. Before he became mayor he had already achieved eminence in the administration of Taiwan (then a Japanese possession) and in the national government.

The first city council was elected in 1889, the year other cities were permitted to elect mayors. There were three classes of electors, divided according to income, each of which elected its own councilmen.

Some very eminent men were returned to the council in that first election, and indeed lists of councilmen through successive elections are worthy of a body with more considerable functions. The Ministry of the Interior had a veto power over acts of the city government and from time to time exercised the power, which had an inhibiting effect on the mayor and the council. Fukuzawa Yukichi, perhaps the most successful popularizer of Civilization and Enlightenment, the rallying call of the new day, was among those elected to the first council. Yasuda Zenjirō, founder of the Yasuda (now the Fuji) financial empire, was returned by the poorest class of electors.

The high standards of the council did not pervade all levels of government. There were scandals. The most sensational was the one known as the gravel scandal. On the day in 1920 that the Meiji Shrine was dedicated (to the memory of the Meiji emperor), part of a bridge just below the shrine collapsed. Investigation revealed that crumbly cement had been used, and this in turn led to revelations of corruption in the city government. The gravel scandal coincided with a utilities scandal, and the mayor, among the most popular the city has had, resigned, to be succeeded by the famous Gotō Shimpei. Tokyo deserves the name it has made for itself as a well-run city, but City Hall does have its venalities from time to time.

The Meiji system, local and national, could hardly be called democratic, but it was more democratic than the Tokugawa system had been. It admitted the possibility of radical departures. Rather large numbers of people, without reference to pedigree, had something to say about how they would be governed. Meiji was a vital period, and gestures toward recognizing plebeian talents and energies may help to account for the vitality. The city suffered from “happy insomnia,” said Hasegawa Shigure, on the night the Meiji constitution went into effect.

Her father made a speech. The audience was befuddled, shouting, “No, no!” when prearranged signals called for “Hear, hear!” and vice versa; but it was happy, so much so that one man literally drank himself to death. It is an aspect of Meiji overlooked by those who view it as a time of dark repression containing the seeds of 1945.

The Meiji emperor, photographed in 1872

The population of the city increased from about the fifth year of Meiji. It did not reach the highest Edo levels until the mid-1880s. The sparsely populated High City was growing at a greater rate than the Low City, though in absolute terms the accretion was larger in the Low City. The new population came overwhelmingly from the poor rural areas of northeastern Japan. Despite its more stable population, the Low City had a higher divorce rate than the High City, and a higher rate than the average for the nation. But then the Low City had always been somewhat casual toward sex and domesticity. It had a preponderantly male population, and Tokyo continues to be one of the few places in the land where men outnumber women. The High City changed more than the Low City in the years between the Restoration and the earthquake, but when sons of Edo lament the death of their city, they refer to the dispersal of the townsman and his culture, the culture of the Low City. The rich moved away and so their patronage of the arts was withdrawn, and certain parts of the Low City, notably those immediately east of the palace, changed radically.

Change, as it always is, was uneven. Having heard the laments of the sons of Edo and turned to scrutinize the evidence, one may be more surprised at the continuity. The street pattern, for instance, changed little between Restoration and earthquake. In his 1874 guide to the city, W. E. Griffis remarked upon “the vast extent of open space as well as the lowness and perishable material of which the houses are built.” Pictures taken from the roof of the City Hall in the last years of Meiji still show astonishing expanses of open land, where once the mansions of the military aristocracy had stood. Photographs from the Nikolai Cathedral in Kanda, taken upwards of a decade earlier, show almost unbroken expanses of low wooden buildings all the way to the horizon, dissolving into what were more probably photographic imperfections than industrial mists.

One would have had to scan the expanses carefully to find precise and explicit survivals among the back alleys of Edo. Fires were too frequent, and the wish to escape the confines of an alley and live on a street, however narrow, was too strong. Yet one looks at those pictures taken from heights and wonders what all those hundreds of thousands of people were doing and thinking, and the very want of striking objects seems to offer an answer. The hundreds of thousands must have been far closer to their forebears of a hundred years before than to the leaders, foreign and domestic, of Civilization and Enlightenment.

Even today the Low City is different from the High City—tighter, more conservative, less given to voguish things. The difference is something that has survived, not something that has been wrought by the modern century.

It was considered very original of Charles Beard, not long before the earthquake, to characterize Tokyo as a collection of villages, but the concept was already familiar enough. John Russell Young, in attendance upon General and Mrs. Grant when they came visiting in 1879, thus described a passage up the river to dine at an aristocratic mansion:

The Prince had intended to entertain us in his principal town-house, the one nearest the Enriokwan, but the cholera broke out in the vicinity, and the Prince invited us to another of his houses in the suburbs of Tokio. We turned into the river, passing the commodious grounds of the American Legation, its flag weather-worn and shorn; passing the European settlement, which looked a little like a well-to-do Connecticut town, noting the little missionary churches surmounted by the cross; and on for an hour or so past tea houses and ships and under bridges, and watching the shadows descend over the city. It is hard to realize that Tokio is a city—one of the greatest cities of the world. It looks like a series of villages, with bits of green and open spaces and inclosed grounds breaking up the continuity of the town. There is no special character to Tokio, no one trait to seize upon and remember, except that the aspect is that of repose. The banks of the river are low and sedgy, at some points a marsh. When we came to the house of the Prince we found that he had built a causeway of bamboo through the marsh out into the river.

The city grew almost without interruption from early Meiji to the earthquake. There was a very slight population drop just before the First World War, to be accounted for by economic disquiet, but by the end of Meiji there were not far from two million people. Early figures, based on family registers, proved to be considerably exaggerated when, in 1908, the national government made a careful survey. It showed a population of about a million and two-thirds. This had risen to over two million by 1920, when the first national census was taken. The 1920 census showed that almost half the residents of the city had been born elsewhere, the largest number in Chiba Prefecture, just across the bay; and so it may be that the complaints of the children of Edo about the new men from the southwest were exaggerated. In the decade preceding the census (the figures are based upon family registers) the three central wards seem to have gained population at a much lower rate than the city as a whole. The most rapid rate of increase was in Yotsuya Ward, to the west of the palace. The High City was becoming more clearly the abode of the elite, now identified more in terms of money than of family or military prowess. Wealthy merchants no longer had to live in the crowded lowlands, and by the end of Meiji most of them had chosen to leave. Asakusa Ward stood first both in population and in population density.

Tokyo had been somewhat tentatively renamed and reorganized, but it passed through the worst of the Restoration uncertainty by the fourth or fifth year of Meiji, and was ready for Civilization and Enlightenment: Bummei Kaika. The four Chinese characters, two words, very old, provided the magical formula for the new day. Bummei is generally rendered as “civilization,” though it is closely related to bunka, usually rendered as “culture.” Kaika means something like “opening” or “liberalization,” though “enlightenment” is perhaps the commonest rendering. Both words are ancient borrowings from Chinese. As early as 1867 they were put together and offered as an alternative to the dark shadows of the past.

“Examining history, we see that life has been dark and closed, and that it advances in the direction of civilization and enlightenment.” Already in 1867 we have the expression from the brush of Fukuzawa Yukichi, who was to coin many another new word and expression for the new day. Though in 1867 Fukuzawa was still a young man, not far into his thirties, the forerunner of what was to become his very own Keiō University had been in session for almost a decade. No other university seems so much the creation of a single man. His was a powerful and on the whole benign personality. In education and journalism and all manner of other endeavors he was the most energetic and successful of propagandizers for the liberal and utilitarian principles that, in his view, were to beat the West at its own game.

For the Meiji regime, Bummei Kaika meant Western modes and methods. Though not always of such liberal inclinations as Fukuzawa, the regime agreed that the new formula would be useful in combatting Western encroachment. Tokyo and Osaka, the great cities of the old day, led the advance, together with the port cities of the new.

The encroachment was already apparent, and it was to be more so with the arrival of large-nosed, pinkish foreigners in considerable numbers. The formal opening of Edo was scheduled to occur in 1862. Unsettled conditions brought a five-year delay. The shogunate continued building a foreign settlement all the same. Tsukiji, on the bay east of the castle and the Ginza district, was selected for reasons having to do with protecting both foreigner from native and native from foreigner. Isolated from the rest of the city by canals and gates and a considerable amount of open space known as Navy Meadow, the settlement was ready for occupation in 1867. The foreign legations, of which there were then eleven, received word some weeks after the Restoration that the opening of the city must wait until more equable conditions prevailed. The government finally announced it towards the end of the year. Several legations, the American legation among them, moved to Tsukiji.

The gates to the settlement were early abandoned, and access became free. Foreigners employed by the government received residences elsewhere in the city, in such places as “the Kaga estate” (Kaga yashiki), the present Hongo campus of Tokyo University. Others had to live in the Tsukiji quarter if they were to live in Tokyo at all. Not many of them did. Tsukiji was never popular with Europeans and Americans, except the missionaries among them. The foreign population wavered around a hundred, and increasingly it was Chinese. Though small, it must have been interesting. A list of foreign residents for 1872 includes a Frenchman described as an “equestrian acrobat.” Among them were, of course, bad ones, opium dealers and the like, and the gentle treatment accorded them by the consulates aroused great resentment, which had the contradictory effect of increasing enthusiasm for Civilization and Enlightenment—faithful application of the formula, it was felt, might persuade foreign powers to do without extraterritoriality.

The two chief wonders of Tsukiji did not lie within the foreign settlement. The Tsukiji Hoterukan was across a canal to the south. The New Shimabara licensed quarter, established to satisfy the presumed needs of foreign gentlemen, was to the north and west, towards Kyōbashi.

The Hoterukan could only be early Meiji. Both the name and the building tell of the first meetings between Meiji Japan and the West. Hoteru is “hotel,” and kan is a Sino-Japanese term of roughly the same meaning. The building was the delight of early photographers and late print-makers. One must lament its short history, for it was an original, a Western building unlike any building in the West. The structure, like its name, had a mongrel air, foreign details applied to a traditional base or frame. The builder was Shimizu Kisuke, founder of the Shimizu-gumi, one of the largest modern construction companies. Shimizu was a master carpenter, or perhaps a sort of building contractor, who came from a province on the Japan Sea to study foreign architecture in Yokohama.

Although the Hoterukan was completed in early Meiji, it had been planned from the last days of Tokugawa as an adjunct to the foreign settlement. It took the shape of an elongated U. Records of its dimensions are inconsistent, but it was perhaps two hundred feet long, with more than two hundred rooms on three floors, and a staff numbering more than a hundred. Tokugawa instincts required that it face away from the sea and towards the nondescript Ginza and Navy Meadow; the original design, taking advantage of the grandest prospect, was reversed by xenophobic bureaucrats, who wished the place to look more like a point of egress than a point of ingress. There was a pretty Japanese garden on the bay side, with a tea cottage and a pergola, but the most striking features of the exterior were the tower, reminiscent of a sixteenth-century Japanese castle, and walls of the traditional sort called namako, or “trepang,” dark tiles laid diagonally with white interstices.

From the outside, little about it except the height and the window sashes seems foreign at all, though perhaps an Anglo-Indian influence is apparent in the wide verandas. Wind bells hung along chains from a weathervane to the corners of the tower. The interior was plastered and painted in the foreign manner.

Through the brief span of its existence, the Hoterukan was among the wonders of the city. Like the quarter itself, however, it does not seem to have been the sort of place people wished to live in. It was sold in 1870 to a consortium of Yokohama businessmen, and in 1872 it disappeared in the great Ginza fire. (It may be of interest to note that this calamity, like the military rising of 1936, was a Two-Two-Six Incident, an event of the twenty-sixth day of the Second Month. Of course the later event was dated by the solar calendar and the earlier one by the old lunar calendar; yet the Two-Two-Six is obviously one of those days of which to be apprehensive.) The 1872 fire began at three in the afternoon, in a government building within the old castle compound.

Fanned by strong winds, it burned eastward through more than two hundred acres before reaching the bay. Government buildings, temples, and mansions of the old and new aristocracy were taken, and fifty thousand people of the lesser classes were left homeless. It was not the largest fire of the Meiji Period, but it was perhaps the most significant. From it emerged the new Ginza, a commercial center for Civilization and Enlightenment and a symbol of the era.

Then there was that other marvel, the New Shimabara. For the accommodation of the foreigner a pleasure quarter was decreed. It was finished in 1869, among the first accomplishments of the new government. The name was borrowed from the famous Shimabara quarter of Kyoto. Ladies arrived from all over the Kantō district, but most of them came from the Yoshiwara. In 1870, at the height of its short career, it had a very large component indeed, considering the small size of the foreign settlement and its domination by missionaries. It followed the elaborate Yoshiwara system, with teahouses serving as appointment stations for admission to the grander brothels. Upwards of seventeen hundred courtesans and some two hundred geisha, twenty-one of them male, served in more than two hundred establishments, a hundred thirty brothels and eighty-four teahouses.

The New Shimabara did not prosper. Its career, indeed, was even shorter than that of the Hoterukan, for it closed even before the great fire. A report informed the city government that foreigners came in considerable numbers to look, but few lingered to play. The old military class also stayed away. Other pleasure quarters had depended in large measure upon a clientele from the military class, but the New Shimabara got only townsmen. In 1870 fire destroyed a pleasure quarter in Fukagawa, across the river (where, it was said, the last of the real Edo geisha held out). The reassigning of space that followed led to the closing of the New Shimabara. Its ladies were moved to Asakusa. There were no further experiments in publicly sponsored (as opposed to merely licensed) prostitution.

The most interesting thing about the quarter is what it tells us of changing official standards. In very early Meiji it was assumed that the foreigner, not so very different from the Japanese, would of course desire bawdy houses. Prudishness quickly set in, or what might perhaps better be described as deference to foreign standards. When the railway was put through to Yokohama, a land trade resulted in a pleasure quarter right beside the tracks and not far from the Yokohama terminus. Before long, the authorities had it moved away. Foreign visitors would think it out of keeping with Civilization and Enlightenment.

The foreign settlement seems to have been chiefly a place of bright missionary and educational undertakings. Such eminent institutions as Rikkyō University, whose English name is St. Paul’s, had their beginnings there, and St. Luke’s Hospital still occupies its original Tsukiji site.

The reaction of the impressionable townsman to the quarter is as interesting as the quarter itself. The word “Christian” had taken on sinister connotations during the centuries of isolation. In appearance so very Christian, the settlement was assumed to contain more than met the eye.

At about the turn of the century Tanizaki Junichirō was sent there for English lessons. Late in his life he described the experience:

There was in those days an English school run by ladies of the purest English stock, or so it was said—not a Japanese among them… Exotic Western houses stood in unbroken rows, and among them an English family named Summer had opened a school. At the gate with its painted louver boards was a wooden plaque bearing, in Chinese, the legend “Bullseye School of European Letters.” No one called it by the correct name. It was known rather as “The Summer.” I have spoken of “an English family,” but we cannot be sure that they were really English. They may have been a collection of miscellaneous persons from Hong Kong and Shanghai and the like. They were, in any event, an assembly of “she foreigners,” most alluring, from eighteen or nineteen to perhaps thirty. The outward appearance was as of sisters, and there was an old woman described as their mother; and there was not a man in the house. I remember that the youngest called herself Alice and said she was nineteen. Then there were Lily, Agnes, and Susa [sic]… If indeed they were sisters, it was curious that they resembled each other so little…

Even for us who came in groups, the monthly tuition was a yen, and it must have been considerably more for those who had private lessons. A yen was no small sum of money in those days. The English lived far better, of course, than we who were among the unenlightened. They were civilized. So we could not complain about the tuition…

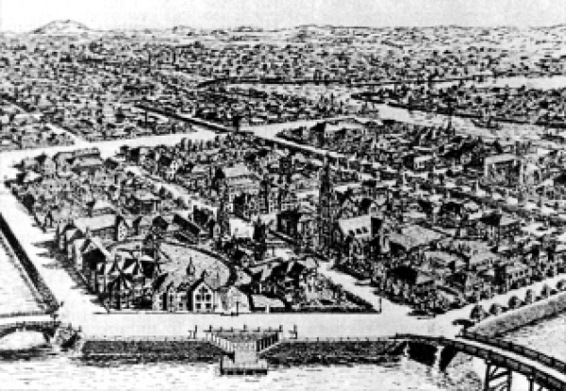

Bird’s-eye view of Tsukiji foreign settlement

Wakita spoke in a whisper when he told me—he had apparently heard it from his older brother—that the she foreigners secretly received gentlemen of the Japanese upper classes, and that they were for sale also to certain Kabuki actors (or perhaps in this instance they were the buyers). The Baikō preceding the present holder of that name, he said, was among them. He also said that the matter of private lessons was a strange one, for they took place upstairs during the evening hours. Evidence that Wakita’s statement was not a fabrication is at hand, in the “Conference Room” column of the Tokyo Shimbun for January 27, 1954. The article, by the recently deceased actor Kawarazaki Gonjūrō, is headed: “On the Pathological Psychology of the Sixth Kikugorō.” I will quote the relevant passage:

“There was in those days an English school in Tsukiji called the Summer. I was sent to it. The old Uzaemon and Baikō, and Fukusuke, who later became Utaemon, had all been there before me, and it would seem that their object had to do less with the English language than with the Sanctuary of the Instincts. Among the Summer girls was a very pretty one named Susa. She was the lure that drew us.”

Later Sasanuma, to keep me company, also enrolled in the Summer. The two of us thought one day to see what the upstairs might be like. We were apprehended along the way, but we succeeded in catching a glimpse of florid decorations.

Here is a description of Tsukiji from another lover of the exotic, the poet Kitahara Hakushu, writing after the settlement had disappeared in the earthquake, not to return:

A ferry—off to Boshū, off to Izu?

A whistle sounds, a whistle.

Beyond the river the fishermen’s isle,

And on the near shore the lights of the Metropole.

This little ditty written in his youth by my friend Kinoshita Mokutarō, and Eau-de-vie de Dantzick, and the print in three colors of a Japanese maiden playing a samisen in an iris garden in the foreign settlement, and the stained glass and the ivy of the church, and the veranda fragrant with lavender paulownia blossoms, and a Chinese amah pushing a baby carriage, and the evening stir, “It’s silver it’s green it’s red,” from across the river, and, yes, the late cherries of St. Luke’s and its bells, and the weird secret rooms of the Metropole, and opium, and the king of trumps, and all the exotic things of the proscribed creed—they are the faint glow left behind from an interrupted dream.

The foreign settlement was rebuilt after the Ginza fire, but not the Hoterukan. As the reminiscences of Hakushū tell us, there were other hotels. The Metropole was built in 1890 on the site of the American legation when the latter moved to the present site of the embassy. The Seiyōken is recommended in Griffis’s guide of 1874. It was already in Tsujiki before the first railway was put through, and food fit for foreigners was brought from Yokohama by runner. The Seiyōken enterprise survives as a huge and famous restaurant in Ueno.

The Tsukiji foreign settlement lost its special significance when, at the end of the nineteenth century, revision of “the unequal treaties” brought an end to extraterritoriality. By way of bringing Japan into conformity with international practice in other respects as well, foreigners were allowed to live where they chose. The quarter vanished in the earthquake and fire of 1923, leaving behind only such mementoes as St. Luke’s.

Very soon after the Restoration the city set about changing from water and pedestrian transport to wheels. A significant fact about the first stage in the process is that it did not imitate the West. It was innovative. The rickshaw or jinrickshaw is conventionally reviled as a symbol of human degradation. Certainly there is that aspect. It might be praised for the ingenuity of the concept and the design, however, and if the city and the nation were determined to spin about on wheels, it was a cheap, simple, and clean way of getting started. Though the origins of the rickshaw are not entirely clear, they seem to be Japanese, and of Tokyo specifically. The most widely accepted theory offers the names of three inventors, and gives 1869 as the date of the invention. The very first rickshaw is thought to have operated in Nihombashi. Within the next few years there were as many as fifty thousand in the city. The iron wheels made a fine clatter on rough streets and bridges, and the runners had their distinctive cries among all the other street cries. The populace does not seem to have paid as close attention as it might have. Edward S. Morse, an American professor of zoology who arrived in the tenth year of Meiji to teach at the university, remarked upon the absentminded way in which pedestrians received the warning cries. They held their ground, as if the threat would go away.

Some of the rickshaws were artistically decorated, and some, it would seem, salaciously, with paintings on their rear elevations. In 1872 the more exuberant styles of decoration were banned. Tokyo (though not yet the provinces) was discovering decorum. Runners were required to wear more than the conventional loincloth. Morse describes how a runner stopped at the city limits to cover himself properly.

For a time in early Meiji four-wheeled rickshaws carrying several passengers and pushed and pulled by at least two men operated between Tokyo and Yokohama. There are records of runners who took loaded rickshaws from Tokyo to Kyoto in a week, and of women runners.

From late Meiji the number of rickshaws declined radically, and runners were in great economic distress. On the eve of the earthquake there were fewer than twenty thousand in the city proper. The rickshaw was being forced out to the suburbs, where more advanced means of transportation were slower in coming.

It was an excellent mode of transport, particularly suited to a crowded city of narrow streets. It was dusty and noisy, to be sure, but no dustier and in other respects cleaner than the horse that was its first genuine competitor. An honest and good-natured runner, not difficult to find, was far less dangerous than a horse. Most people seem to have liked the noise—leastways Meiji reminiscences are full of it. Rubber tires arrived, and the clatter went away, though the shouting lingered on. The best thing about the rickshaw, perhaps, was the sense it gave of being part of the city.

Even this first and simplest vehicle changed the city. The canals and rivers became less important, and places dependent on them, such as old and famous restaurants near the Yoshiwara, went out of business. Swifter means of transportation come, and people take to them. Yet it seems a pity that the old ones disappeared so completely. The rickshaw is gone today, save for a few score that move geisha from engagement to engagement.

In its time the rickshaw itself was the occasion for the demise of another traditional way of getting about. The palanquin, which had been the chief mode of transport for those who did not walk, almost disappeared with the sudden popularity of the rickshaw. It is said that after 1876, with the departure for Kagoshima of the rigidly conservative Shimazu Saburō of the Satsuma clan, palanquins were to be seen only at funerals and an occasional wedding. The bride who could not afford a carriage and thought a rickshaw beneath her used a palanquin. With the advent of motor hearses and cheap taxis the palanquin was deprived of even these specialized functions.

The emperor had his first carriage ride in 1871, on a visit to the Hama Detached Palace, where General and Mrs. Grant were to stay some years later. Horse-drawn public transportation followed very quickly after the first appearance of the rickshaw. There were omnibuses in Yokohama by 1869, and not many years later—the exact date is in doubt—they were to be seen in Ginza. A brief span in the 1870s saw two-level omnibuses, the drivers grand in velvet livery and cocked hats. The first regular route led through Ginza from Shimbashi on the south and on past Nihombashi to Asakusa. Service also ran to Yokohama, and westwards from Shinagawa, at the southern edge of the city. The horse-drawn bus was popularly known as the Entarō, from the name of a vaudeville story-teller who imitated the bugle call of the conductor, to great acclaim. Taxis, when their day came, were long known as entaku, an acronym from Entarō and “taxi,” with the first syllable signifying also “one yen.”

The horse trolley arrived in 1883. The first route followed the old omnibus route north from Shimbashi to Nihombashi, and eventually to Asakusa. In the relentless advance of new devices, horse-drawn transportation had a far shorter time of prosperity than in Europe and America. There was already experimentation with the electric trolley before the horse trolley had been in use for a decade. An industrial exposition featured an electric car in 1890. In 1903 a private company laid the first tracks for general use, from Shinagawa to Shimbashi, and later to Ueno and Asakusa. The electric system was very soon able to carry almost a hundred thousand passengers a day, for lower fares than those asked by rickshaw runners, and so the rickshaw withdrew to the suburbs. Initially in private hands, the trolley system was no strong argument for private enterprise. There were three companies, and the confusion was great. In 1911, the last full year of Meiji, the city bought the system.

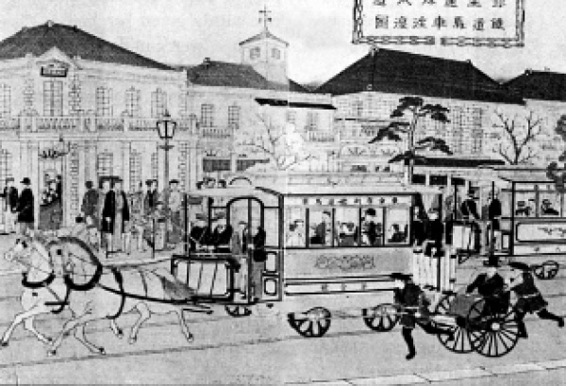

Horse-drawn buses in Ginza Bricktown, from a print by Hiroshige III (Courtesy Tokyo Central Library)

The confusion is the subject of, or the occasion for, one of Nagai Kafū’s most beautiful prose lyrics, “A Song in Fukagawa” (Fukagawa no Uta), written in 1908. The narrator boards a trolley at Yotsuya and sets forth eastwards across the city. As it passes Tsukiji, an unplanned but not unusual event occurs, which sends him farther than he has thought to go.

The car crossed Sakura Bridge. The canal was wider. The lighters moving up and down gave an impression of great activity, but the New Year decorations before the narrow little shops and houses seemed punier, somehow, than in Tsukiji. The crowds on the sidewalks seemed less neat and orderly. We came to Sakamoto Park, and waited and waited for a sign that we would be proceeding onwards. None came. Cars were stopped in front of us and behind us. The conductor and motorman disappeared.

“Again, damn it. The damned powers gone off again.” A merchant in Japanese dress, leather-soled pattens and a cloak of rough, thick weave, turned to his companion, a redfaced old man in a fur muffler.

A boy jumped up, a delivery boy, probably. He had a bundle on his back, tied around his neck with a green kerchief.

“A solid line of them, so far up ahead you can’t see the end of it.”

The conductor came running back, change bag under his arm, cap far back on his head. He mopped at his brow.

“It might be a good idea to take transfers if you can use them.”

Most of us got up, and not all of us were good-humored about it.

“Can’t you tell us what’s wrong? How long will it be?”

“Sorry. You see how it is. They’re stopped all the way to Kayabachō…”

Caught in the general rush for the doors, I got up without thinking. I had not asked for one, but the conductor gave me a transfer to Fukagawa.

So Kafū finds himself east of the river, and meditates upon the contrast between that backward part of the city and the advanced part from which he has come. He yearns for the former, and must go back and live in the latter; and we are to suppose that he would not have had his twilight reverie if the trolley system had functioned better.

The rickshaw changed patterns of commerce by speeding people past boat landings. The trolley had a more pronounced effect, the Daimaru dry-goods store being a case in point. It was one of several such establishments that were to develop into department stores. Established in Nihombashi in the eighteenth century, it was in mid-Meiji the most popular of them all, even more so than Mitsukoshi, foundation of the Mitsui fortunes. “The Daimaru,” said Hasegawa Shigure, “was the center of Nihombashi culture and prosperity, as the Mitsukoshi is today.” In her girlhood it was a place of wonder and excitement. It had barred windows, less to keep burglars out than to keep shop boys (there were no shop girls in those days) in. Sometimes a foreign lady with foxlike visage would come in to shop, and the idle of Nihombashi would gather to stare. But the Daimaru did not lie, as its rivals did, on a main north-south trolley line. By the end of the Meiji it had closed its Tokyo business and withdrawn to the Kansai, whence only in recent years it has returned to Tokyo, this time not letting the transportation system pass it by. It commands an entrance to Tokyo Central Station.

For some, Nagai Kafū among them, the trolley was a symbol of disorder and ugliness. For others it was the introduction to a new world, at once intimidating and inviting. The novelist Natsume Sōseki’s Sanshirō, a university student from the country, took the advice of a friend and dashed madly and randomly about, seeking the rhythms of this new world.

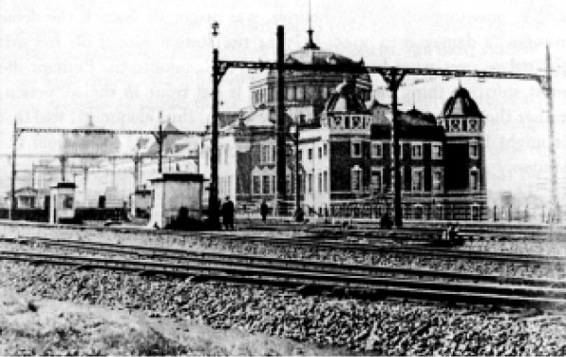

Construction of a railway, financed in London, began in 1870. The chief engineer was English, and a hundred foreign technicians and workers were engaged to run it. Not until 1879 were trains entrusted to Japanese crews, and then only for daylight runs. The first line was from Shimbashi, south of Ginza, to Sakuragichō in Yokohama, a stop that still serves enormous numbers of passengers, though it is no longer the main Yokohama station. The Tokyo terminus was moved some four decades later to the present Tokyo Central Station, and the old Shimbashi Station became a freight office, disappearing in 1923.

Daimaru Department Store, Nihombashi. Woodcut by Kiyochika

The very earliest service, in the summer of 1872, was from Shinagawa, just beyond the southern limits of the city, to Yokohama. The Tokyo terminus was opened in the autumn, amid jubilation. The emperor himself took the first train He wore foreign dress, but most of the high courtiers were in traditional court dress; Western dress was still expensive and very difficult to come by. Among the notables present was the king of Okinawa.

The fare was higher than for a boat or horse-drawn bus. Everyone wanted a ride, but only the affluent could afford a ride daily. Eighty percent of the passengers are said to have been merchants and speculators with business in Yokohama. The first tickets carried English, German, and French translations. From 1876 on, there was only English.

It was in 1877 that an early passenger, E. S. Morse, made his famous discovery of the shell middens of Omori, usually considered the birthplace of Japanese archeology. The train took almost an hour to traverse its twenty-five kilometers, and Omori was then a country village offering no obstructions, and so, without leaving his car, Morse was able to contemplate the mounds at some leisure and recognize them for what they were.

The Tokyo-Yokohama line was the first segment of the Tokaidō line, put through from Tokyo to Kobe in 1889. Unlike the Tokaidō, the main line to the north was built privately, from Ueno. It was completed to Aomori, at the northern tip of the main island, in 1891. By the turn of the century private endeavor had made a beginning at the network of suburban lines that was to work such enormous changes on the city; in 1903 Shibuya Station, outside the city limits to the southwest, served an average of fifteen thousand passengers a day. When it had been first opened, less than two decades before, it served only fifteen.

Shimbashi Station possessed curious ties with the Edo tradition. The Edo mansion of the lords of Tatsuno had stood on the site. Tatsuno was a fief neighboring that of the Forty-seven Loyal Retainers of the most famous Edo vendetta. The Forty-seven are said to have refreshed themselves there as they made their way across the city, their vendetta accomplished, to commit suicide.

If the railroad caused jubilation, it also brought opposition. The opposition seems to have been strongest in the bureaucracy. Carrying Yokohama and its foreigners closer to the royal seat was not thought a good idea. If a railroad must be built, might it not better run to the north, where it could be used against the most immediately apparent threat, the Russians? Along a part of its course, just south of the city, it was in the event required to run inland, because for strategic reasons the army opposed the more convenient coastal route.

Among the populace the railway does not seem to have aroused as much opposition as the telegraph, about which the wildest rumors spread, associating it with the black magic of the Christians and human sacrifice. People seem to have been rather friendly towards the locomotive. Thinking that it must be hot, poor thing, they would douse it with water from embankments.

By the eve of the earthquake there were ten thousand automobiles in the city, but they did not displace the railroad as railroad and trolley had displaced the rickshaw. In one important respect they were no competition at all. When the railroad came, the Ukiyo-e print of Edo was still alive. The art, or business, had considerable vigor, though many would say that it was decadent. Enormous numbers of prints were made, millions of them annually in Tokyo alone, almost exclusively in the Low City. Few sold for as much as a penny. They were throwaways, little valued either as art or as investment. Nor were technical standards high. Artists did not mind and did not expect their customers to mind that the parts of a triptych failed to join precisely. Bold chemical pigments were used with great abandon. Yet Meiji prints often have a contagious exuberance. They may not be reliable in all their details, but they provide excellent documents, better than photographs, of the Meiji spirit. Losses over the years have been enormous. Today such of them as survive are much in vogue, bringing dollar prices that sometimes run into four figures, or yen prices in six figures.

The printmakers of early Meiji loved trains and railroads. Many of the prints are highly fanciful, like representations of elephants and giraffes by people who have never seen one. A train may seem to have no axles, and to roll on its wheels as a house might roll on logs. Windows are frivolously draped, and two trains will be depicted running on the same track in collision course, as if that should be no problem for something so wondrous. The more fanciful images can seem prophetic, showing urban problems to come, smog, traffic jams, a bureaucracy indifferent to approaching disaster.

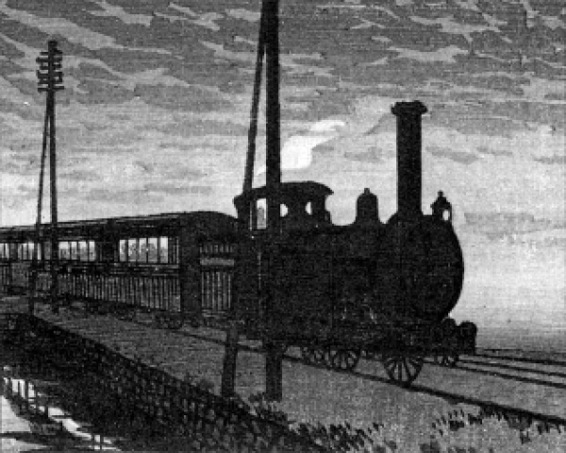

Train on Takenawa embankment. Woodcut by Kiyochika

Sometimes the treatment was realistic. The manner of Kobayashi Kiyochika, generally recognized as the great master of the Meiji print is both realistic and effective, as beautiful a treatment of such unlikely subjects as railroads, surely, as is to be found anywhere.

Kiyochika was born in Honjo, east of the Sumida, in 1847, near the present Kyōgoku Station and not far from the birthplace of the great Hokusai. The shogunate had lumber and bamboo yards in the district. His father was a labor foreman in government employ. Though the youngest of many sons, Kiyochika was named the family heir, and followed the last shogun to Shizuoka. The shogun in exile was himself far from impoverished, but many of his retainers were. Kiyochika put together a precarious living at odd jobs, one of them on the vaudeville stage. Deciding finally to return to Tokyo, he stopped on the way, or so it is said—the details of his life are not well established—to study art under Charles Wirgman, the British naval officer who became Yokohama correspondent for the Illustrated London News. Missing nothing, Kiyochika is said also to have studied photography under Shimooka Renjō, the most famous of Meiji photographers, and painting in the Japanese style as well.

His main career as a printmaker lasted a scant five years, from 1876 to 1881, although he did make an occasional print in later life. In that brief period he produced more than a hundred prints of Tokyo. The last from the prolific early period are of the great Kanda fire of 1881, in which his own house was destroyed. (That fire was, incidentally, the largest in Meiji Tokyo.)

All the printmakers of early Meiji used Western subjects and materials, but Kiyochika and his pupils (who seem to have been two in number) achieved a Western look in style as well. It may be that, given his Westernized treatment of light and perspective, he does not belong in the Ukiyo-e tradition at all.

The usual Meiji railway print is bright to the point of gaudiness, and could be set at any hour of the day. The weather is usually sunny, and the cherries are usually in bloom. Kiyochika is best in his nocturnes. He is precise with hour and season, avoiding the perpetual springtide of his elders. His train moves south along the Takanawa hill and there are still traces of color upon the evening landscape; so one knows that the moon behind the clouds must be near full.

The prints of Kiyochika’s late years, when he worked mostly as an illustrator, are wanting in the eagerness and the melancholy of prints from the rich early period. The mixture of the two, eagerness and melancholy, seems almost prophetic—or perhaps we think it so because we know what was to happen to his great subject, the Low City. His preference for nocturnes was deeply appropriate, for there must have been in the life of the Low City this same delight in the evening, and with it a certain apprehension of the dawn.

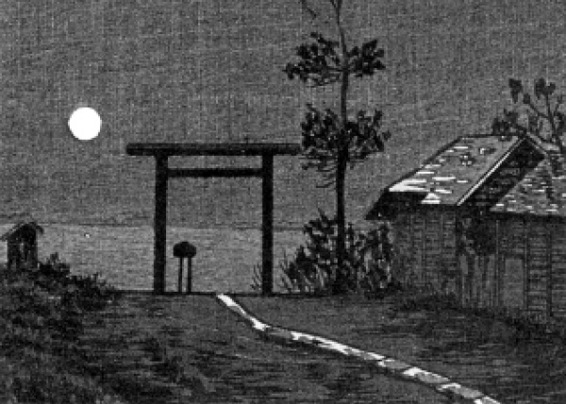

Shrine near the Yoshiwara. Woodcut by Inoue Yasuji, after Kiyochika

The lights flooding through the windows of Kiyochika’s Rokumeikan, where the elite of Meiji gathered for Westernized banquets and balls, seem about to go out. Lights are also ablaze in the great and venerable restaurant outside the Yoshiwara, but they seem subdued and dejected, for the rickshaws on their way to the quarter do not stop as the boats once did. In twilight fields outside the Yoshiwara stands a little shrine, much favored by the courtesans. Soon (we know, and Kiyochika seems to know too) the city will be flooding in all around it. Other little shrines and temples found protectors and a place in the new world, but this one did not. No trace of it remains.

Kiyochika had a knack one misses in so many travel writers of the time for catching moods and tones that would soon disappear. Other woodcut artists of the day, putting everything in the sunlight of high spring, missed the better half of the picture. Kiyochika was a gifted artist, and that period when Edo was giving way to Tokyo provided fit subjects for the light of evening and night. He outlived the Meiji emperor by three years.

The importance of the waterways declined as the city acquired wheels and streets were improved. The system of rivers, canals, and moats had been extensive, drawing from the mountains to the west of the city and the Tone River to the north. Under the shogunate most of the produce brought into the city had come by water. At the end of Taishō, or three years after the earthquake, most of it came by land. This apparent shift is something of a distortion, since it ignores Yokohama, the international port for Tokyo. The decline of water transport is striking all the same. There was persistent dredging at the mouth of the Sumida, but Tokyo had no deep harbor. It could accommodate ships of not more than five hundred tons. All through the Meiji Period the debate continued as to whether or not the city should seek to become an international port. Among the arguments against the proposal was the old xenophobic one: a harbor would bring in all manner of foreign rogues and diseases. What is remarkable is that such an argument could still be offered seriously a half-century after the question of whether or not to have commerce with foreign rogues had presumably been settled.

The outer moats of the palace were filled in through the Meiji Period, and the Tameike reservoir, to the southwest of the palace, which had been among the recommended places in guides to the pleasures of Edo for gathering new herbs in the spring and, in high summer, viewing lotus blossoms and hearing them pop softly open, was allowed to gather sediment. Its military importance having passed, it became a swamp in late Meiji, and in Taishō quite disappeared.

The system of canals was still intact at the end of Meiji, and there were swarms of boats upon them and fish within them. Life on the canals and rivers seems to have been conservative even for the conservative Low City. An interesting convention in the woodcuts of Meiji is doubtless based upon fact. When bridges are shown, as they frequently are, the roadway above is generally an exuberant mixture of the new and the traditional, the imported and the domestic; on the waters below there is seldom a trace of the new and imported.

Pleasure-boating of the old sort almost disappeared. Advanced young people went rowing on the Sumida, and the university boathouse was one of the sights on the left bank. A 1920 guide to Japan, however, lists but a single funayado in the city. The funayado, literally “boat lodge” or “boating inn,” provided elegant boating for entertainment on the waters or for an excursion to the Yoshiwara. The boats were of the roofed, high-prowed sort, often with lanterns strung out along the eaves, that so often figure in Edo and Meiji woodcuts. Since the customer expected to be entertained as well as rowed, the funayado provided witty and accomplished entertainers, and so performed services similar to those of the Yoshiwara teahouses. As the network of canals disappeared, some of them made the transition into the new day and became the sort of restaurant to which geisha are summoned, but a great many merely went out of business. Ginza and Kyōbashi were the southern terminus for passage to the Yoshiwara. The funayado of that region were therefore among the ingredients from which the Shimbashi geisha district, still one of the finest in the city, was made.

Connoisseurs like Nagai Kafū said that Edo died of flood and fire, but it may be that the loss of boats and waterways had an even more destructive effect on the moods of Edo. Kafū himself implies as much when, in an elegiac evocation of late Edo, he has a famous writer set forth from a funayado and take stock of events. He is a victim of the puritanical edicts of the 1840s, and a quiet time on the Sumida is best for surveying the past and the future. The wheels of Meiji disrupted old patterns and rhythms. There was no longer the time or the inclination to put together a perfect outing, and so the arts of plebeian Edo were not in demand as they once had been.

This is not to say that the moods of the Sumida, so important to Edo, were quite swept away. They were still there, if somewhat polluted and coarsened. A “penny steamer” continued to make its way up and down the river, and on to points along the bay, even though it had by the time of the earthquake come to cost more than a penny. Ferries across the river were not completely replaced by bridges until after the Second World War. The most conservative of the geisha quarters, Yanagibashi, stood beside the river, and mendicant musicians still had themselves paddled up and down before it. One could still go boating of a summer night with geisha and music and drink. The great celebration called the “river opening” was the climactic event of the Low City summer.

The Yaomatsu restaurant on the Sumida, looking towards Asakusa

In 1911 and 1912 the playwright Osanai Kaoru published an autobiographical novel called Okawabata (The Bank of the Big River, with reference to the Sumida). Osanai was a pioneer in the Westernized theater. Some years after the earthquake he was to found the Little Theater of Tsukiji, most famous establishment in an energetic and venturesome experimental-theater movement. Like Nagai Kafū, whose junior he was by two years, he was a sort of Edokko manqué. His forebears were bureaucratic and not mercantile, and he had the added disability that he spent his early childhood in Hiroshima. Such people often outdid genuine Edokko, among whom Tanizaki Junichirō could number himself, in affection for the city and especially vestiges of Edo, abstract and concrete. The Bank of the Big River has the usual defects of Japanese autobiographical fiction—weak characterization, a rambling plot, a tendency towards self-gratification; but it is beautiful in its evocation of the moods of the Sumida. The time is 1905 or so, with the Russo-Japanese War at or near a conclusion. The setting is Nakasu, an artificial island in the Sumida, off Nihombashi.

Sometimes a lighter would go up or down between Ohashi Bridge and Nakasu, an awning spread against the sun, banners aloft, a sad chant sounding over the water to the accompaniment of bell and mallet, for the repose of the souls of those who had died by drowning.

Almost every summer evening a boat would come to the stone embankment and give us a shadow play. Not properly roofed, it had a makeshift awning of some nondescript cloth, beneath which were paper doors, to suggest a roofed boat of the old sort. Always against the paper doors, yellowish in the light from inside, there would be two shadows… When it came up the river to the sound of drum and gong and samisen, Masao would look happily at Kimitarō, and from the boat there would be voices imitating Kabuki actors…

Every day at exactly the same time a candy boat would pass, to the beating of a drum. Candy man and candy would be like distant figures in a picture, but the drum would sound out over the river in simple rhythm, so near that he might almost, he thought, have reached out to touch it. At the sound he would feel a nameless stirring and think of home, forgotten so much of the time, far away in the High City. The thought was only a thought. He felt no urge to leave Kimitarō.

The moon would come up, a great, round, red moon, between the godowns that lined the far bank. The black lacquer of the river would become gold, and then, as the moon was smaller and whiter, the river would become silver. Beneath the dark form of Ohashi Bridge, across which no trolleys passed, it would shimmer like a school of whitefish.

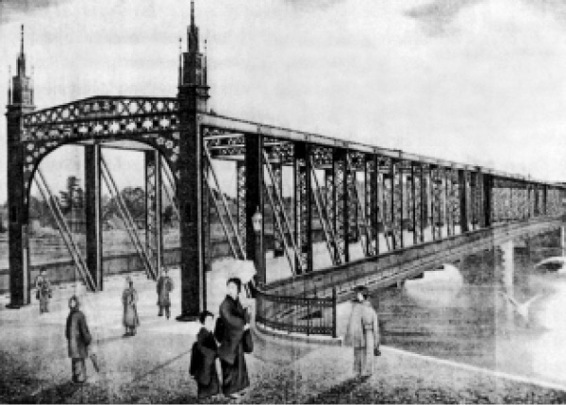

The old wooden bridges, so pretty as they arched their way over river and canal, were not suited to heavy vehicular traffic. Wood was the chief material for wider and flatter bridges, but steel and stone were used for an increasing number of important new ones. Of 481 bridges in the city at the end of the Russo-Japanese War, 26 were steel and 166 were stone. The rest were wood. A new stone Nihombashi was dedicated in 1911. It is the Nihombashi that yet stands, and the one for which the last shogun wrote the inscription. He led the ceremonial parade, and with him was a lady born in Nihombashi a hundred years before, when there were yet four shoguns to go. The famous Azuma Bridge at Asakusa, often called “the big bridge,” was swept away by a flood in 1885. A steel Azuma Bridge with a decorative superstructure was finished in 1882, occasioning a great celebration at the dedication, geisha and lanterns and politicians and all. It quickly became one of the sights of the city. The floor was still wooden at the time of the earthquake. It caught fire, as did all the other bridges across the river; hence, in part, the large number of deaths by drowning.

Azumabashi, Asakusa. From a lithograph dated 1891

Nagai Kafū accused the Sumida, which he loved, of flooding twice annually. “Just as when summer gives way to autumn, so it is when spring gives way to summer: there are likely to be heavy rains. No one was surprised, for it happened every year, that the district from Senzoku toward the Yoshiwara should be under water.”

So begins the last chapter of his novella The River Sumida. It is an exaggeration, and in other respects not entirely accurate. Late summer and autumn was the season for floods. The rains of June are more easily contained than the violent ones of the typhoon season. The passage of the seasons so important to Kafū’s story required a flood in early summer. Records through the more than three centuries of Edo and Meiji suggest that the Sumida flooded on an average of once every three years. It may be that, for obscure reasons, floods were becoming more frequent. In the last half of Meiji the rate was only a little less than one every two years, and of eight floods described as “major, two were in late Meiji, in 1907 and 1910.

The flood of 1910, commonly called the Great Meiji Flood, submerged the whole northern part of the Low City, eastwards from the valleys of Koishikawa. Rising waters breached the levees of the Sumida and certain lesser streams. Asakusa, including the Yoshiwara and the setting of the Kafū story, suffered the worst damage, but only one of the fifteen wards was untouched, and the flood was a huge disaster.The damage has been calculated at between 4 and 5 percent of the national product for that year. Kafū liked to say that Edo disappeared in the Great Flood and the Yoshiwara fire of the following year. The flood was the occasion for the Arakawa Drainage Channel, to put an end to Sumida floods forever (see page 257).

Of all Meiji fires, the Ginza fire of 1872 had the most lasting effect upon the city. From it emerged the new Ginza.

Ginza had not been one of the busier and more prosperous sections of mercantile Edo. Compared to Nihombashi, farther north, it was cramped and narrow, caught between the outer moats of the great Tokugawa citadel and a bay shore occupied in large measure by the aristocracy. The great merchant houses were in more northerly regions. Ginza was a place of artisans and small shops.

W. E. Griffis gave a good account of what he saw there in 1870, before the fire. It contained no specific reference to Ginza, but a long walk, on his first visit to the city, took him from Tsukiji and the New Shimabara (which he wrongly calls the Yoshiwara) to Kanda. It must have been the Ginza district through which he first strolled.

I pass through one street devoted to bureaus and cabinets, through another full of folding screens, through another of dyers’ shops, with their odors and vats. In one small but neat shop sits an old man, with horn-rimmed spectacles, with the mordant liquid beside him, preparing a roll of material for its next bath. In another street there is nothing on sale but bamboo poles, but enough of these to make a forest. A man is sawing one, and I notice he pulls the saw with his two hands toward him. Its teeth are set contrary to ours. Another man is planing. He pulls the plane toward him. I notice a blacksmith at work: he pulls the bellows with his foot, while he is holding and hammering with both hands. He has several irons in the fire, and keeps his dinner boiling with the waste flame… The cooper holds his tub with his toes. All of them sit while they work. How strange! Perhaps that is an important difference between a European and an Asian. One sits down to his work, and the other stands up to it…

I emerge from the bamboo street to the Tori, the main street, the Broadway of the Japanese capital. I recognize it. The shops are gayer and richer; the street is wider; it is crowded with people.

Turning up Suruga Chō, with Fuji’s glorious form before me, I pass the great silk shop and fire-proof warehouses of Mitsui the millionaire.

Ginza had once been something of a theater center, until the Tempō edicts of the 1840s removed the Kabuki theaters to the northern suburbs. Theater quickly returned to the Ginza region when it was allowed to, after the Restoration, but the beginning of Ginza as a thriving center of commerce and pleasure came after the fire.

The governor decided that the city must be made fireproof, and the newly charred Ginza offered a place to begin. An English architect, Thomas Waters, was retained to build an entire district of red brick. The government subsidized a special company “for building and for the management of rentals.” The rebuilding took three years, when it could have been accomplished in the old way almost overnight. Rather proud of its fires, the old city had also been proud of the speed with which it recovered.

There seem to have been at least two brick buildings in the Ginza district even before the great fire, one of them a warehouse, the other a shop, “a poorer thing than the public latrines of later years,” says an eminent authority on the subject. When the rebuilding was finished there were almost a thousand brick buildings in Kyōbashi Ward, which included Ginza, and fewer than twenty in the rest of the city. An 1879 list shows a scattering of Western or Westernized buildings through most of the other wards, and one ward, Yotsuya in the High City, with none at all.

The hope was that the city would make itself over on the Ginza model, and become fireproof. Practice tended in the other direction. Only along the main street was a solid face of red brick presented to the world. Very soon there was cheating, in the form of reversion to something more traditional. Pictures from late Meiji inform us that Bricktown, as it was called, lasted longest in what is now the northern part of Ginza. Nothing at all survives of it today.

Ginza Bricktown, with trees

The new Ginza was not on the whole in good repute among foreigners. Already in the 1870s there were complaints about the Americanization of the city. Isabella Bird came visiting in 1878 and in 1880 described Tokyo as less like an Oriental city than like the outskirts of Chicago or Melbourne. She did not say what part of the city she had reference to, but almost certainly it was Ginza. Pierre Loti thought that Bricktown had about it une laideur americaine. Philip Terry, the English writer of tour guides, likened it, as Griffis had likened Nihombashi, to Broadway, though not with Griffis’s intent to praise. “Size without majesty, individuality divorced from all dignity and simplicity, and convenience rather than fitness or sobriety are the salient characteristics of this structural hodge-podge.” Not much of Bricktown survived when Terry wrote, in 1920. What did survive was the impression of a baneful American influence; and the original architect was English.

The city was of two minds about its new Ginza. Everyone wanted to look at it, but not many wanted to live in it. In a short story from early in this century, Nagai Kafū described it as a chilling symbol of the life to come.

The initial plans were for shops on the ground floors and residential quarters above, after the pattern of merchant Edo. The new buildings were slow to fill. They were found to be damp, stuffy, vulnerable to mildew, and otherwise ill adapted to the Japanese climate, and the solid walls ran wholly against the Japanese notion of a place to live in. Choice sites along the main street presently found tenants, but the back streets languished, or provided temporary space for sideshows, “bear wrestling and dog dances” and the like. Among the landowners, who had not been made to relinquish their rights, few were willing or able to meet the conditions for repaying government subsidies. These were presently relaxed, but as many as a third of the buildings on the back streets remained empty even so. Vacant buildings were in the end let go for token payments, and cheating on the original plans continued apace. Most Edo townsmen could not afford even the traditional sort of fireproof godown, and the least ostentatious of the new brick buildings were, foot for foot, some ten times as expensive. Such fireproofing measures as the city took through the rest of Meiji went no farther than widening streets and requisitioning land for firebreaks when a district had been burned over.

Despite the views of Miss Bird and Loti, the new Ginza must have been rather handsome. It was a huge success as an instance of Civilization and Enlightenment, whatever its failures as a model in fireproofing. Everyone went to look at it, and so was born the custom of Gimbura, “killing time in Ginza,” an activity which had its great day between the two world wars.

The new Ginza was also a great success with the printmakers. As usual they show it in brilliant sunlight with the cherries in bloom; and indeed there were cherries, at least in the beginning, along what had become the widest street in the city, and almost the only street wide enough for trolleys. There were maples, pines, and evergreen oaks as well, the pines at intersections, the others between.

It is not known exactly when and why these first trees disappeared, leaving the willow to become the great symbol of Ginza. The middle years of Meiji seem to have been the time. Perhaps the original trees were victims of urbanization, and perhaps, sprawling and brittle and hospitable to bugs, they were not practical. Willows, in any event, took over. Hardy and compact, riffled by cooling breezes in the summer, they were what a busy street and showplace seemed to need. Long a symbol of Edo and its rivers and canals, the willow became a symbol of the newest in Tokyo as well. Eventually the willow too went away. One may go out into the suburbs, near the Tama River, and view aged specimens taken there when, just before the earthquake, the last Ginza willows were removed.

With the new railway station just across a canal to the south, the southern end of what is now Ginza—it was technically not then a part of Ginza—prospered first. From middle into late Meiji it must have been rather like a shopping center, or mall, of a later day. There were two bazaars by the Shimbashi Bridge, each containing numbers of small shops. The youth of Ginza, we have been told by a famous artist who was a native of the district, loved to go strolling there, because from the back windows the Shimbashi geisha district could be seen preparing itself for a night’s business. One of the bazaars kept a python in a window. The python seems to have perished in the earthquake. From the late Meiji Period into Taishō, Tokyo Central Station was built to replace Shimbashi as the terminus for trains from the south. It stood at the northern boundary of Kyōbashi Ward, and so Ginza moved back north again to center upon what is now the main Ginza crossing.

At least one building from the period of the new Ginza survives, Elocution Hall (Enzetsukan) on the Mita campus of Keiō University. Fukuzawa Yukichi invented the word enzetsu, here rendered as “elocution,” because he regarded the art as one that must be cultivated by the Japanese in their efforts to catch up with the world. Elocution Hall, put up in 1875 and now under the protection of the government as a “cultural property” of great merit, was to be the forum for aspiring young elocutionists. It was moved from the original site, near the main entrance to the Keiō campus, after the earthquake. It is a modest building, not such as to attract the attention of printmakers, and a pleasing one. The doors and windows are Western, as is the interior, but the exterior, with its “trepang walls” and tiled roof, is strongly traditional. In its far more monumental way, the Hoterukan must have looked rather thus.

The great Ginza fire of 1872 is rivaled as the most famous of Meiji fires by the Yoshiwara fire of 1911, but neither was the most destructive. The Ginza fire burned over great but not consistently crowded spaces. The Kanda fire of 1881, the one that brought an end to Kiyochika’s flourishing years as a printmaker, destroyed more buildings than any other Meiji fire. And not even that rivaled the great fires of Edo, or the Kyoto fire of 1778. Arson was suspected in the 1881 fire, as it was suspected, and sometimes proved, in numbers of other fires. It was a remarkable fire. Not even water stopped it, as water had stopped the Ginza fire. Beginning in Kanda and fanned by winter winds, it burned a swath through Kanda and Nihombashi, jumped the river at Ryogoku Bridge, and burned an even wider swath through the eastern wards, subsiding only when it came to open country.

The great Yoshiwara fire of 1911