LOW CITY, HIGH CITY

The old Tōkaidō highway from Kyoto and Osaka ran through Ginza and crossed one last bridge, Kyōbashi, “Capital Bridge,” before it came to its terminus at the Nihombashi bridge. The boundary between the two wards, Nihombashi and Kyōbashi, crossed the old highway at a point halfway between the two bridges. They have since been combined to make Chūō Ward, which means Central Ward, and indeed they were central to the Low City, the only two wards that lay completely in the Low City by any definition.

Seen together they have an agreeably solid and stable shape, from the Hama Palace at the southwest to Ryōgoku bridge at the northeast. When they are separated into the two Meiji wards, a difference becomes apparent. Because it keeps reaching out into lands reclaimed from the bay, the southern half, the Kyōbashi half (with Ginza inside it), has the more expansive look today. In early Meiji and in Edo it was the constricted half.

Both districts were largely cut off from the Sumida and the bay by bureaucratic and aristocratic establishments. Yet it would have been possible at the beginning of Meiji to walk the mile or so northeastwards across Nihombashi from the outer moat of the palace to the river and see no aristocratic walls. Only two or three hundred yards eastwards, across the Ginza district in southern Kyōbashi, one would have bumped into the first of them. Whether so planned or not, the Tokugawa prison in the center of Nihombashi was as far removed on all sides from the aristocracy as any point in the city. On land-use maps of late Edo, Nihombashi seems the only district where the townsman had room to breathe. By the end of Meiji the upper classes, whether of the new plutocracy or the old aristocracy, had almost completely departed the Low City, and so Nihombashi, solidly plebeian from the outer moat to the river, looks yet more expansive. So does Kyōbashi, filled out by reclamation and largely relieved of the aristocracy.

A new distinction took the place of the old. Nihombashi was rich and powerful (though the shogunate in theory granted no power to merchants), the heart of commercial Edo. There the rich merchant lived and there the big stores were, Mitsui and Daimaru and the like. Kyōbashi was poorer and more dependent on the patronage of the aristocracy, a place of lesser shopkeepers and of artisans.

This was the historical difference. In Meiji the difference was between the new and the old, the modern and the traditional. After the opening of the Tokyo-Yokohama railroad and its own rebuilding, Ginza, in southern Kyōbashi, emerged as the part of the city most sensitive and hospitable to foreign influences. Nihombashi remained the center of the mercantile city, though toward the end of Meiji Marunouchi had begun its rise.

The Mitsui Bank in Nihombashi

It is a simplification. The northern part of Kyōbashi, beyond the Kyobashi Bridge, did not plunge into the new world as eagerly as Ginza to the south did, and Nihombashi was at once conservative and the site of the modern buildings most celebrated by ukiyo-e artists. The Hoterukan in Tsukiji, the southeastern part of Kyōbashi, was the earliest such building and certainly much celebrated, but it lasted a very short time. Blocks of brick, not individual buildings, were what the artists liked about Ginza. Nihombashi provided them with their best—and largest—instances of Civilization and Enlightenment.

So it is a simplification. Yet if one had wished a century ago to wander about in search of what it was that Meiji was departing from, one would have been wise to choose Nihombashi. If the quest was for the city of the future, Kyōbashi would have been the better choice. At a somewhat later date one could have gone to the Rokumeikan, in Kōjimachi to the west, but that was an elite sort of place, not for everyone every day. One needed an invitation, and social ambitions would have helped too.

Much about the Meiji Ginza, and the Rokumeikan as well, is charming in retrospect. One would have loved being there, and one must lament that nothing at all survives, save those willow trees out by the Tama River. Much of the charm is in the fact that all is so utterly gone, and if to the person with antiquarian tendencies Ginza is today pleasanter than certain other centers of the advanced and the chic, that is because it is less advanced and chic than they. A century ago it would have been the most extremely chic of them all. Nihombashi on the contrary was the place with the coziest past, and, except for the parts nearest the palace and later the central railway station, the place most reluctant to part with that past. Today one must go farther to the north and east for suggestions of the old city that in Meiji were within a few minutes’ walk of the foreign settlements.

At the proud forefront of Civilization and Enlightenment, the inner, affluent side of Nihombashi was later blessed with the new Bank of Japan, finished in 1896, and said to be the first genuinely foreign building of monumental proportions put up entirely by Japanese. Nihombashi was thus the financial center of the country, more modern, in a way, than Ginza even after Bricktown was built, because it was there and in government offices that the grand design for modernity was put together.

These modern structures, and the big department stores as well, were within a few paces of the Nihombashi bridge. Right there northeast of the bridge was also the fish market. It is striking in late Meiji how little of the modern and Western there is in a northeasterly direction from the bridge, off towards the Sumida. When, after the earthquake, Tanizaki rejected Tokyo and moved to the Kansai, he did it in a particularly pointed manner because he was rejecting his native Nihombashi, the very heart of the old city.

The Nihombashi Fish Market, about 1918

The First National Bank in Nihombashi

Nihombashi occupies the choice portion of the land earliest reclaimed from tidal marshes, the first Low City. It looks ample on Meiji maps, right there at the Otemon, the front gate of castle and palace. It is bounded on the north and east by water, and cut by the Nihombashi River, the busiest canal in the city. All this water suggests commerce. It is less watery than the wards east of the river, but the latter look, on maps of the Meiji city, as if they were still in process of reclamation, while Nihombashi looks as if reclamation had been accomplished long ago, and the canals left from the marshes for good, productive reasons. Very little of Meiji remains in Nihombashi, and scarcely anything of Edo. Already in Meiji the wealthy, liberated from old class distinctions and what had in effect been a system of zoning, were moving to more elegant places. Already, too, Ginza and Marunouchi were rising to challenge its entrepreneurial supremacy. Yet there is something conservative about the air of the place. It has welcomed grand commercial and financial castles in the modern manner, but it has not welcomed glitter. It has never flashed as Ginza has, or been a playground like Asakusa.

In photographs looking eastwards from the Mitsukoshi Department Store, across the main north-south street, there is little on the eve of the earthquake that could not have survived (whether after all those fires it did or not) from Edo. There are modern buildings on the east side of the street, which was the great dividing line, and there is a financial cluster north of the Nihombashi River, where the Yasuda Bank, now the enormous Fuji, started growing; there too, at the juncture of the Nihombashi and the Sumida, the Bank of Japan had its first building, designed by Condor. For the most part, however, low roofs and wooden buildings in the grid pattern of the earliest years stretch on to the Sumida. It was among the parts of the Low City that had a smaller proportion of streets to buildings at the end of Meiji than at the beginning, and it looks that way. It is as if the snugness of Edo were still present, even though one knows that it could not have been. Vast numbers of country people had moved in and people like the Mitsuis had moved out, and the diaspora of the children of Edo (made so much of by people like Tanuaki) was well underway. Still the sense one has of conservatism is not mistaken.

The western part of Nihombashi did not begin going really modern until fairly late in Meiji. On the whole, Nihombashi was slower to change than Ginza or Marunouchi. The Nihombashi River was still at the end of Meiji lined by the godowns, some of them converted into dwellings, that had always been a symbol of the district and its mercantile prosperity. The Tanizaki family lived for a time in a godown. E. S. Morse wrote enthusiastically of converted godowns, which were doubtless ingenious, but other accounts inform us that they were as damp and badly aired as ever the Ginza bricktown was.

A row of merchant houses in Nihombashi, about 1919

The aristocracy did not occupy much of old Nihombashi, and neither did the religions. There were shrines, though what was to become the most famous and popular of them, the Suitengū, Shrine of the Water God, was moved from another part of the city only in early Meiji. There were a few Buddhist temples, most of them founded in Meiji, half of them on the site of the old Tokugawa prison, dismantled in 1875. Initially they had a propitiatory function.

Nihombashi was not without pleasures, but moderate about them, perhaps in this regard nearer the Tokugawa ideal than Asakusa or Ginza. Not since the removal of the Yoshiwara to the northern paddies after the great fire of 1657 (the occasion also for moving most Nihombashi temples to the paddies) had Nihombashi provided the more elaborate and expensive of pastimes. Nevertheless, it was in the Hamachō geisha quarter, near the river in Nihombashi, that O-ume romantically murdered Minekichi. Hamachō was a modest quarter compared to Yanagibashi in Asakusa Ward to the north and Shimbashi to the south. Of the major theaters in the city today, the Meijiza in Nihombashi has the longest history. Probably at no time, except perhaps briefly when rivals were rebuilding from fires, could it have been described as the premier theater of the city. Yet it has survived, eminent but not supreme. This seems appropriate to conservative, steady Nihombashi.

The Mitsui Bank in Nihombashi, by Kiyōchika

The Mitsui Bank and the First National Bank of early Meiji were both torn down at about the time the new Bank of Japan was going up. Printmakers contrived to show the two buildings in isolation, or perhaps to imagine what they would have been like had it been possible to view them in isolation. Photographers could not or did not achieve the same effect. There can have been nothing like them in Edo, except perhaps, in a very vague way, the castle keep. Yet they do not look out of place. They are as if imagined by someone who had never actually seen a Western building (in fact the builder of both had studied in Yokohama), and whose idea of the Western was the traditional made bigger and showier.

There is nothing Japanese about the Bank of Japan. It is a pleasing enough building, but it is obviously the creation of someone who had studied Western architecture well and did not presume to have ideas of his own. Very much the same can be said of the Mitsui buildings that went up on or near the site of the early Meiji bank. Only the Bank of Japan and some bridges—one of them the main Nihombashi Bridge itself and one of them, the Tokiwa, the oldest stone bridge in the city—survive from Meiji. The brick Mitsui buildings and the new stone building of the First National Bank have long since gone the way of their more fanciful predecessors.

The early buildings would obviously not have lent themselves to the purposes of increasingly monstrous economic miracles. Yet both institutions, the Mitsui Bank and the Daiichi Kangyō Bank, as it is now, are so hugely rich that they could have set aside their first sallies into Western design as museums, and so enabled us to see for ourselves something that cannot be quite the same in photographs and prints—something confused, perhaps, but also lovable, like a child trying to look regal in clothes brought down from the attic. Of course, since most of Nihombashi was lost in 1923, it is likely that the two buildings would have vanished then even if the mercies of the banks had been more tender.

So Nihombashi did not stand apart from all the Meiji changes. There were changes that were still invisible. Nihombashi may to this day perhaps be called the financial center of the city and the land, for it has the Bank of Japan and the stock exchange; but big management has for the most part moved elsewhere. Neither of the two banks that so delighted the printmakers has its main offices in Nihombashi. The beginnings of the shift may be traced to late Meiji. Rival centers were growing, to the south and west; the big movements in the modern city have consistently been to the south and west.

The novelist Tayama Katai came to Tokyo in 1881 as a boy of ten, and was apprenticed to a publishing house in Nihombashi. More than half a century later he mused upon the contrast between the old Nihombashi and Ginza, and between the parts of Nihombashi, bustling commerce on the one hand and stagnation on the other.

There was not a day when I did not cross the Nihombashi and Kyōbashi bridges. A dank, gloomy Nihombashi main street, lined mostly with earthen walls, as against the bricks of Ginza, across Kyōbashi. Entaro horse-drawn omnibuses sped past, splashing mud and sending forth trumpet calls. On the right side a short distance north of the Nihombashi Bridge…two or three doors from each other, were two large bookstores, the Suwaraya and the Yamashiroya, their large, rectangular shop signs dignified and venerable, of a sort that one sees in Edo illustrations. Yet what gloomy, deserted stores they were! Two or three clerks in Japanese dress would always be sitting there, in abject boredom, and I did not once see a customer come in to buy a book. The contrast with the house on the corner, the Echigoya, forerunner of the Mitsukoshi, could not have been more complete. One can still find the latter, I believe, in old pictures, a one-story building with a long veranda, livening the district with an incessant shouting. It sounded rather like “Owai, owai.” Customers were seated in rows, and the noise emerged from clerks ordering apprentices to get wares from the godown. Not only the Echigoya: on a corner towards the north and east was the yet larger Daimaru, and from it came that same “Owai, owai” …

Ginza was then in the new style, with what were called its streets of brick, but from Kyōbashi to Nihombashi and on to Spectacle Bridge there was scarcely a building in the Western style…

I was in Peking some years ago, and the crowding and confusion outside the Cheng-yang Gate—a pack of little shops and stalls, bystanders munching happily away at this and that—reminded me of early Meiji. It was indeed no different from the stir and bustle, in those days, at the approaches to the Nihombashi Bridge.

All up and down the main Nihombashi street there were shops with displays of polychrome woodcuts…

Off towards Asakusa were shops with displays of something approaching erotica. I was somewhat surprised—no, I should say that I would stand on and on, fascinated, as if, in that day when there were no magazines worthy of the name, I were gazing at life itself, and the secrets deep within it. But I doubt that the approaches to the Nihombashi Bridge of Edo were in such disorder. In the confusion something still remained of very early Meiji. I grow nostalgic for it, that air of the degenerate.

Nihombashi was wealthy, and it was poor and crowded. It had its gloomy back streets, lined by windowless godowns, and it had its entertainment quarter, off towards the river, on land once occupied by the aristocracy. Land in Nihombashi was, or so the popular image had it, worth its volume in gold, but for a decent garden in any of the lands reclaimed by the shogunate one had to import loam from the hills. Great care and expense went into little gardens squeezed in among the godowns. Besides gardeners, there were dealers in earth—not land but earth—brought in to make mossy gardens. By late Meiji the very wealthy had left, but it was still not uncommon for the middle ranks of the mercantile class to have houses and gardens in Nihombashi even if they owned land in the High City.

Tanizaki wrote about the dark back streets of eastern Nihombashi, only a short walk from the entertainment districts. If he remarked upon the contrast with Ginza on the south, Hasegawa Shigure contrasted it with Kanda, on the north. She had an aunt in Kanda, and it was there that she had glimpses of the West not to be had in Nihombashi.

She took me to see the Nikolai Cathedral, then under construction. It was when I stayed with her that I first heard the sound of violin and piano and orchestra. In our part of the Low City such sounds and such instruments were quite unknown. So it was that I first caught the scent of the West. Kanda was where the students had their dens, where the intelligentsia, as we would call it today, assembled.

Katai thought the confusion of Nihombashi unlike Edo. The reminiscences of Shigure, who was born in Nihombashi in 1879, make it sound very much like Edo as it has remained in art and fiction.

On a late summer evening the breeze would come from the river as the tide rose. Hair washed and drying, bare feet, paper lanterns, platforms for taking the evening cool, salty cherry-blossom tea—all up and down the streets, under the stars, was the evening social, not to be savored by the rich ones and the aristocrats. It was easier and freer than the gathering in the bathhouse. The rows of houses were the background and the streets were the gathering place. If a policeman happened to be living in one of the row houses, he would become a human being once more, and join the assembly, hairy chest bare, kimono tucked up, a fan of tanned paper in his hand. He would not reprove the housewife if too much of her was exposed, and took it as a matter of course that the man next door should be out wearing nothing but a loincloth…

Shinnai balladry would come, and Gidayū, and koto and samisen together. They were not badly done, for they had a knowledgeable audience. Strange, wonderful, distant strains would emerge from the gardens of the teahouses… The samisen and the koto duos were mostly played by old women, most of them from the old Tokugawa bureaucratic class.

Just as in the lumberyards of Fukagawa no native was until the earthquake to be seen wearing a hat, so too it was in my part of Nihombashi. Down to the turn of the century a hat was a rare sight. The only hatted ones were men of affluence in party dress.

Photographs from late Meiji of eastern Nihombashi give an impression of changelessness, low-tiled roofs stretching on and on, but it is perhaps somewhat misleading. Edo must have been even thus, one thinks, and one forgets that the low roofs stretched over a wider expanse at the end of Meiji than at the end of Edo. The abodes of the less affluent stretched now all across Nihombashi to the river, as they had not in Edo. Such places of pleasure as Nihombashi did have—the quarter where Minekichi got stabbed, the shrine that had the liveliest feast days—stood mostly on land once occupied by the aristocracy. The departure of the aristocracy was not in any case the loss that the departure of the wealthy merchant class was. Though the pleasure quarters had been heavily dependent on the furtive patronage of the aristocracy, it had not provided open patronage, and it had remained aloof from the city around it. So perhaps an irony emerges: the changes that occurred in eastern Nihombashi through Meiji may have been of a reactionary nature. The area may have been more like the Low City of Edo at the end of Meiji than at the beginning.

Nihombashi Bridge looking east, 1911

Nihombashi was proud of itself, in a quiet, dignified sort of way. The young Tanizaki was infatuated with the West and insisted upon rejection of the Japanese tradition, but he never let us forget that he was from Nihombashi. Perhaps more in Meiji than in Tokugawa it was the place to which all roads led—for a powerless court in Kyoto still then had powerful symbolic import.

Pride in self commonly brings (or perhaps it arises from) conservatism. In certain respects Nihombashi, especially its western reaches, was every bit as high-collar, as dedicated to Civilization and Enlightenment, as Ginza. Yet it was far from as ready to throw away everything in pursuit of the new and imported. If Nihombashi and Ginza represent the two sides of Meiji, conservative and madly innovative, Nihombashi by itself can be seen as representative of contradictions that were not after all contradictions. Now as in the seventh and eighth centuries, when China came flooding in, innovation is tradition.

It has continued to be thus, even down to our day. The last Meiji building in Ginza has just been demolished. The Bank of Japan yet stands. Nihombashi itself—which is to say, the corps of its residents—has probably had less to do with the preservation of the latter than the Ginza spirit has had to do with the destruction of the former. Yet there is fitness in this state of affairs. Nihombashi did not, like the Shinagawa licensed quarter, explicitly reject change; but perhaps it was the more genuinely conservative of the two.

On the eve of the earthquake there were probably more considerable expanses of Edo in Nihombashi than anywhere else in the city. Even today, when one has to hunt long for a low frame building of the old sort, Nihombashi looks far less like New York than do Ginza and Shinjuku. As a summer twilight gives way to darkness in eastern Nihombashi, one can still sense the sweet melancholy that Kafū so loved, and observe the communal cheerfulness that Shigure described so well.

Kyōbashi was a place of easier enthusiasms. On the north it merged with Nihombashi. To the south of the “Capital Bridge” from which it took its name, it was narrower and poorer, a district of artisans, for the most part, where it was a plebeian district at all. Considerably under half of the lands south of the bridge and the canal which it crossed belonged to the townsman.

In Meiji the Ginza district, in the southern part of Kyōbashi, changed abruptly. Some might have said that it ran to extremes as did no other part of the city. The original Ginza was the “Silver Seat” of the shogunate, one of its mints, moved from Shizuoka to the northern part of what is now Ginza early in the Tokugawa Period, and moved once more, to Nihombashi, in 1800. The name stayed behind, designating roughly the northern half of what is now Ginza. It may be used to refer to the lands lying between the Kyōbashi Bridge on the north and the Shimbashi Bridge on the south. (The ward extended yet further north.) In this sense it was the place where the West entered most tumultuously.

Kyōbashi was a very watery place, wateriest of the fifteen wards, save Fukagawa east of the river, where the transport, storage, and treatment of the city’s lumber supply required a network of pools and canals. The Ginza district was entirely surrounded by water, and the abundance of canals to the east made the Kyōbashi coast the obvious place for storing unassimilable alien persons. They could be isolated from the populace, and vice versa, by water. Virtually all of the canals are now gone.

The Tōkaidō of the shoguns was the main north-south street in Meiji, and the main showplace of the new Bricktown. It still is the main Ginza street. In other respects Ginza has shifted.

Business and fun tended in a southerly direction when the railroad started bringing large numbers of people in from the south. If there was a main east-west street in this watery region it was the one the shogun took from the castle to his bayside villa, the Hama Palace of Meiji. It is now called Miyukidōri, “Street of the Royal Progress,” because the emperor used it for visits to the naval college and the Hama Palace. Presently a street was put through directly eastwards from the southern arc of the inner palace moat, somewhat to the north of the Street of the Royal Progress. When Ginza commenced moving north again, with the extension of the railroad to the present central station, the crossing of the two, the old Tōkaidō and the street east from the inner moat, became the center of Ginza, and of the city. This was a gradual development, somewhat apparent in late Meiji, but not completely so, perhaps, until Taishō. Though the matter is clouded by the enormous growth of centers to the west, it might be said that the main Ginza crossing is still the center of the city. There was a span of decades, from late Meiji or from Taishō, when almost anyone, asked to identify the very center, would have said Ginza, and, more specifically, the main Ginza crossing.

Both the fire and the opening of the railroad occurred in 1872. The two of them provided the occasion for the great change, which was not as quick in coming as might have been expected. Bricktown, parts of it ready for occupancy by 1874, was too utterly new. It was the rage among sightseers, but not many wanted to stay on and run the risk of turning, as rumor had it, all blue and bloated, like a corpse from drowning. (There were other rumors, too, emphasizing, not unreasonably, the poor ventilation and the dampness.) In the early eighties, midway through the Meiji Period, the new Ginza really came to life. In 1882 horse-trolley service began on the main street, northwards through Nihombashi, with later extension to Asakusa. That same year there were arc lights, turning Ginza into an evening place. The age of Gimbura, a great Taishō institution, had begun. Gimbura is a contraction of Ginza and burabura, an adverb which indicates aimless wandering, or wandering which has as its only aim the chance pleasure that may lie along the way. It originally referred to the activities of the young Ginza vagrant, to be seen there at all hours. The emergence of the pursuit as something for all young people, whether good-for-nothing or not, came at about the time of the First World War.

Ginza began prospering by day as well. What was known as “the Kyōbashi mood” contrasted with the Nihombashi mood. One characterization of the contrast held Nihombashi to be for the child of Edo, Ginza for the child of Tokyo. In a later age it might have been said that Nihombashi still had something for the child of Meiji, while Ginza was for the child of Taishō, or Shōwa. Nihombashi contains relics of Meiji, and nothing at all remains, no brick upon another, of the Ginza Bricktown. The last bit of Meiji on the main Ginza street, completed as that reign was giving way to Taishō, has now been torn down. The Ginza of Meiji is commonly called a place of the narikin. A narikin is a minor piece in Oriental chess that is suddenly converted into a piece of great power. It here refers to the nouveau riche. As pejorative in Japanese as it is in French, the expression contrasts the entrepreneurs of Ginza with such persons as the Mitsui of Nihombashi.

The new people of Ginza were not such huge successes as the Mitsui, or the Iwasaki, with their Mitsubishi Meadow, but they were perhaps more interesting. Their stories have in them more of Meiji venturesomeness and bravery, and help to dispel the notion, propagated by Tanizaki Junichirō among others, that the children of Edo were lost in the bustle and enterprise of the new day.

All up and down Ginza were Horatio Algers, and possibly the most interesting of them was very much a son of Edo. Hattori Kintarō, founder of the Seiko Watch Company, was born to the east of the Ginza district proper, the son of a curio dealer, and apprenticed to a hardware store in the southern part of what is now Ginza. Across the street was a watch shop, in business before the Restoration, which he found more interesting than hardware. Refused apprenticeship there, he became apprenticed instead to a watch dealer in Nihombashi. He also frequented the foreign shops in Yokohama, and presently set up his own business, a very humble one, a street stall in fact. (Ginza had street stalls until after the Second World War.) The watch was among the symbols of Civilization and Enlightenment. An enormous watch is the mark of the Westernized dandy in satirical Meiji prints. Hattori had come upon a good thing, but only remarkable acumen and industry thrust him ahead of enterprises already well established. Within a few years he had accumulated enough capital to open a retailing and repair business of a more solidly sheltered sort, at the old family place east of Ginza. In 1885, when he was still in his twenties, he bought a building at what was to become the main Ginza crossing, the offices of a newspaper going out of business. The Hattori clock tower, in various incarnations, has been the accepted symbol of Ginza ever since. The same year he built the factory east of the river that was to grow into one of the largest watch manufacturers in the world.

It is not a story with its beginnings in rags, exactly, for he came from a respectable family of Low City shopkeepers. All the same, there is in it the essence of Ginza, spread out before the railway terminal that was the place of ingress and egress for all the new worlds of Meiji, and their products, such as watches, which no high-collar person of Meiji could be without. If the Rokumeikan, a few hundred yards west of Ginza, was the place where the upper class was seeking to make political profit from cosmopolitanism, the Hattori tower, there where the two trolley lines were to cross, marked the center of the world for mercantile adventuring.

Other instances of enterprise and novelty abounded. Shiseidō, the largest and most famous manufacturer of Western cosmetics, had its start in a Ginza pharmacy just after the great fire. The founder had been a naval pharmacist. He experimented with many novel things—soap, toothpaste, ice cream—before turning to the task, as his advertising had it, of taking the muddiness from the skin of the nation. His choice of a name for his innovative enterprise contained the Meiji spirit. It is a variant upon a phrase found in one of the oldest Chinese classics, signifying the innate essence of manifold phenomena. Today a person with such a line for sale would be more likely, if he wished a loan word, to choose a French or English one.

It was not only the great houses in Nihombashi that profited from an alliance with the bureaucracy. In early Meiji there were in Kyōbashi Ward two confectioneries with the name Fūgetsudō, one in what is now Ginza, the other north of the Kyōbashi Bridge. It was a model contest between the new and the old. The northern one sold traditional sweets, the southern one cookies and cakes of the Western kind. During the Sino-Japanese War the latter received a huge order for hardtack, upwards of sixty tons. The traditional Fūgetsudō admitted defeat, and the innovative Fūgetsudō, House of the Wind and the Moon, became the most famous confectioner in the city. The most successful of early bakeries, also a Ginza enterprise, had General Nogi among its patrons, and he helped bring it huge profits during his war, the Russo-Japanese War.

July 4, 1899, was a day to remember for several reasons, one of them being the end of the “unequal treaties,” another the opening of the first beer hall in the land, near the Shimbashi end of Ginza. Very late in Meiji, Ginza pioneered in another institution, one that was to become a symbol of Taishō. This was the “café,” forerunner of the expensive Ginza bar. Elegant and alluring female company came with the price of one’s coffee, or whatever. The Plantain was the first of them, founded in 1911 not far from the Ebisu beer hall, at the south end of Ginza. The region had from early Meiji contained numerous “dubious houses” and small eating and drinking places, mixed in among more expensive geisha establishments. The Plantain was still there in 1945, when it was torn down in belated attempts to prepare firebreaks. Shortly after it opened it began to have competition. The still more famous Lion occupied a corner of the main Ginza crossing, and had among its regular customers Nagai Kafū, the most gifted chronicler of the enterprising if somewhat trying life of the café lady. One of them tried to blackmail him.

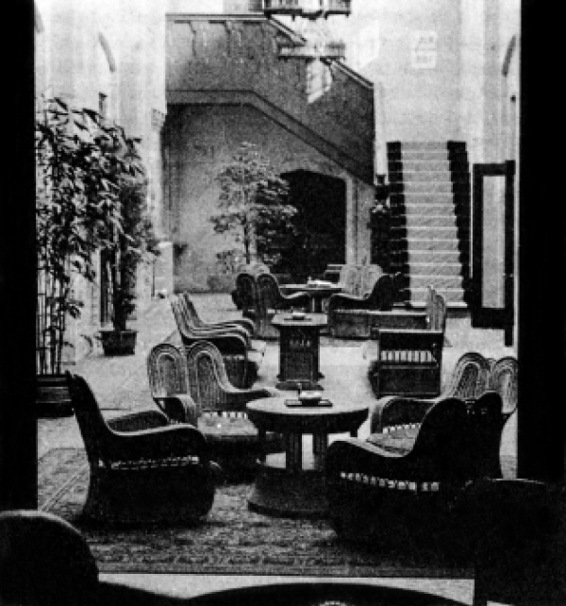

The lobby of the Kōjunsha

Ginza had the first gentlemen’s social club, the Kōjunsha, founded in 1880. The name, a neologism compounded of elements suggesting conviviality and sincere, open discussion, was coined by Fukuzawa Yukichi, a great coiner of new words and the most important publicist for Westernization. He was the founder of Keiō University and the builder of its elocution hall, towards that same end. Japanese must learn public speaking, argued Fukuzawa, and they must also become capable of casual, gentlemanly converse. The Kōjunsha was Fukuzawa’s idea, and the money for it was provided by friends. It opened near Shimbashi in 1880 and is still there, just a hundred years old, in a building put up after the earthquake and already a period piece in the newness of Ginza.

The emperor himself was stumped by one enterprising Ginza merchant. On his way to Ueno in 1889 to open an industrial exposition, he saw in the northern part of Ginza a shop sign which he could not read. The name of the owner was clear enough, but the article purveyed was not, and the emperor was a man well educated in the classics. A courtier was sent to make inquiry. He came back with the information that the commodity in question was the briefcase. The shopkeeper had put together the characters for “leather” and “parcel,” and assigned them a pronunciation recently borrowed from China and indicating a container. Awed by the royal inquiry, the shopkeeper inserted a phonetic guide. The shop sign became famous, and the word and the character entered the language and have stayed there. The sign was burned in 1923.

Some of the most famous modern educational institutions had their beginnings in the southern part of Kyōbashi Ward. The first naval college occupied a site near the foreign settlement. The commercial college that became Hitotsubashi University was founded in 1875 by Mori Arinori, most famous of Meiji education ministers, assassinated for his Westernizing ways on the day in 1889 when the Meiji constitution went into effect. Fukuzawa drafted the statement of purpose, a somewhat prophetic one: the coming test of strength would be mercantile, and victory could not be expected without a knowledge of the rules. His disciples learned the rules very well. Opened as Mori’s private school in very modest quarters, the second floor of a purveyor of fish condiments, the college moved in 1876 to Kobikichō, east of Ginza proper. It was taken over by the city, and in 1885 by the Ministry of Education, which moved it to Kanda.

The middle school and girls’ school that were the forerunners of Rikkyō or St. Paul’s University had their origins in the Tsukiji foreign settlement, and by the end of Meiji had not moved far away. The origins of another famous missionary school, the Aoyama Gakuin, also lay in the foreign settlement of early Meiji, but by the end of Meiji it had moved into the southwestern suburbs.

Ginza did not, in this regard, stay for long at the forefront of Civilization and Enlightenment. The foreign settlement was gone as a legal entity by the end of Meiji, though foreigners continued to live and preach and teach there until the earthquake; but the missionary schools were moving elsewhere and all would soon be gone, leaving only the naval college as a place of higher education.

* * *

In another field of modern cultural endeavor Ginza quickly began to acquire a preeminence which it still in some measure maintains. Though not on the whole very popular, the Ginza brick buildings early caught the fancy of journalists. The newspaper is a modern institution, with a slight suggestion of ancestry in the “tile-print” broadsheets of Edo. The first daily newspaper in Japan was founded in 1870, moving from Yokohama to Ginza in 1879. Originally called the Yokohama Mainichi (the last half of the name meaning “daily”), it became the Tokyo Mainichi in 1906, after several changes of name between. It is not to be confused with the big Mainichi of today, which had a different name in Meiji, and was, with the Asahi, an intruder from Osaka.

The earliest Ginza newspaper—it occupied the site of the Hattori clock tower—seems to have been founded in the Tsukiji foreign settlement by an Englishman, J. R. Black. He was somewhat deceitfully treated by the government, which wished to purge Japanese-language journalism of foreigners. Offered a government job, he accepted it, and as soon as he was safely severed from his newspaper, the job was taken away. Late in Meiji an English performer in the variety halls had a certain vogue. He was the son of J. R. Black. The vogue did not last, and the son died in obscurity shortly after the earthquake.

In mid-Meiji, the Ginza contained as many as thirty newspaper offices. It was at this point that Osaka enterprise moved in, and, by its aggressive methods, reduced competition. At the end of Meiji, there were fewer papers in the city and in Ginza than there had been two or three decades before. Two of the big three had their origins in Osaka, and all three were, at the end of Meiji, in Ginza. The Yomiuri, the only native of Tokyo among the three, stayed longest in Ginza, and now it too is gone. Large numbers of regional newspapers still have Ginza offices, but middle and late Meiji was the great day for Ginza journalism.

Nihombashi may have had the most romantic of Meiji murders, but Ginza had an equally interesting one, of a curiously old-fashioned sort. What is believed to have been the last instance of the classical vendetta reached its denouement just north of the old Shimbashi station in 1880. The assassin, who avenged the death of his parents, was of military origins, his family having owed fealty to a branch of the great Kuroda family of Fukuoka. His parents were killed during the Restoration disturbances—victims, it seems, of clan politics. No attempt was made to punish their murderer; he was in fact treated well by his lord and then by the Meiji government, under which he made a successful career as a judge. After duty in the provinces he was assigned to the Tokyo Higher Court. The son of the murdered couple came up from Kyushu and spent his days stalking. On the chosen day, having failed to come upon his prey outside the court chambers, the vengeful son proceeded to the Kutoda house in what is now Ginza, and made polite inquiry as to the judge’s whereabouts. The unhappy man chanced upon the scene and was stabbed to death. The son received a sentence of life imprisonment but was released in 1892, whereupon he went home to Kyushu to live out his days. Though vendettas had been frowned on by the old regime and were considered quite inappropriate to Civilization and Enlightenment, a certain admiration for this sturdy fidelity to old ways may account for the leniency shown in this instance. The Kuroda family moved away from Kyōbashi two years later and took up residence in the High City, not far from Keiō University. They would doubtless have left soon enough even if the incident had not sullied the old residence. It was the pattern. The area is today thrivingly commercial.

The prominence of the Ginza district in the theater was partly a result of things that happened in Meiji, when both the Shintomiza and the Kubukiza went up a few paces east of Ginza proper. It had an earlier theatrical tradition, from the very early years of the shogunate down to the Tempō edicts of the 1840s. It was the setting for a most delicious bit of theatrical impropriety: A lady in the service of the mother of the seventh shogun fell madly in love with an actor. Pretending to do her Confucian duty in visits to the Tokugawa tombs, she arranged assignations. When it all came out, the actor and the theater manager were exiled to a remote island, and the theater closed. The lady was sent off into the mountains of central Japan. One may still view the melodrama on the Kabuki stage.

Many are the delights in reading of Meiji Ginza. The ardor with which it pursued the West is infectious, and the mercantile adventuring of which it was the center has brought the land the affluence and the prestige that military adventuring failed to do. Both kinds of adventuring inform us persuasively that in modern Japan the realm of action has been more interesting than that of contemplation. Of the two the mercantile kind has certainly been the more effective and probably it has been the more interesting as well. Doubt and equivocation have characterized the realm of thought, whose obsessive themes are alienation and the quest for identity, not so very different from the sort of thing that exercises the modern intellectual the world over. It also dwells at great length on helplessness, the inability of tiny, isolated Japan to survive on its own resources and devices. Meanwhile the manufacturer and the salesman, by no means helpless, have been doing something genuinely extraordinary. The beginning of the way that has brought us to semiconductors and robots is in Meiji Ginza. Gimbura beneath the neon lights of a spring or summer evening is still such a pleasure that one looks nostalgically back to the day when Ginza was the undisputed center of the city and of the land. Yet Ginza and Gimbura have taken on a patina. There are noisier and more generously amplified entertainment and shopping centers to the south and west, and it is to them that the young are inclined to swarm. Gimbura has the look of a slightly earlier time. When it was all the rage, the person who now feels nostalgia for the Ginza of old might well have been drawn more strongly to conservative Nihombashi, where it was still possible to wander in the Edo twilight.

Had one gone about asking townsmen at the beginning of Meiji to define the northern limits of the Low City, there would probably have been a difference of opinion. Some would have said that it ended at the Kanda River or slightly beyond, and so included only Nihombashi, the flat part of Kanda, and perhaps a bit more. Others might have been more generous, and extended it to include the merchant quarters around the Asakusa Kannon Temple and below the Tokugawa tombs at Ueno. These last were essentially islands, however, cut off from the main Low City by aristocratic and bureaucratic lands.

At the end of Meiji everyone would have included Asakusa and Shitaya wards, the latter incorporating Ueno. These wards had filled up and the upper classes had almost vanished, along with many of the temples and cemeteries. Except for a few remaining paddy lands, the Low City reached to the city limits, and in some places spilled beyond.

“The temple of Kuanon at Asakusa is to Tōkiō what St. Paul’s is to London, or Nôtre Dame to Paris,” said W. E. Griffis. It was a place that fascinated most foreigners, even Isabella Bird, who did not for the most part waver in her determination to find unbeaten tracks. Griffis was right, though Asakusa was more than a religious center—or rather it was a Japanese sort of religious center, one which welcomed pleasure to the sacred precincts.

Griffis’s description was perhaps more telling than he realized. “At the north end are ranged the archery galleries, also presided over by pretty black-eyed Dianas, in paint, powder, and shining coiffure. They bring you tea, smile, talk nonsense, and giggle; smoke their long pipes with tiny bowls full of mild, fine-cut tobacco; puff out the long white whiffs from their flat-bridged noses; wipe the brass mouth-piece, and offer it to you; and then ask you leading and very personal questions without blushing… Full grown, able-bodied men are the chief patrons of these places of pleasure, and many can find amusement for hours at such play.”

The description suggests “places of pleasure” in a more specific sense, and indeed that is what they were. The back rooms were for prostitution—right there in the yard (the back yard, but still the yard) of the great temple. More than one early foreign visitor remarked, with a certain not unpleasant confusion, upon a very large painting of a courtesan which hung in the main hall, but no one seems to have noted the true nature of the archery stalls.

Griffis’s description extends over more than a chapter of his memoirs. It is lively and it is sad. Today some tiny outbuildings and a stone bridge survive from Edo, and nothing else, save a few perdurable trees. The melancholy derives not only from physical change; if most of the buildings are gone, so too is most of the life. The main buildings, which had survived the earthquake, were lost in 1945. Asakusa continued even so to be a pleasure center. Then, gradually, people stopped coming. Troops of rustic pilgrims still visit the temple, but the urban crowds, and especially the young, go elsewhere. Asakusa was too confident. With its Kannon and its Yoshiwara, it had, so it thought, no need of railroads, and it was wrong.

Asakusa and Shitaya, from what is now Ueno Park to the Sumida, were a part of the zone of temples and cemeteries extending in a great sweep around the Tokugawa city. One could have walked from where the northernmost platforms of Ueno Station now stand nearly to the river, passing scarcely anything but temples. Plebeian houses, waiting to be flooded every two or three years, lined the river bank itself. (The riverside park of our own day was laid out after the earthquake.) Edo was a zoned city, and among the zones was one for the dead. Not wanting them too near at hand, the shogunate established a ring of necropoles at the city limits. Many temples remained at the end of Meiji and a scattering remains today, making Asakusa and Shitaya the most rewarding part of the city for the fancier of tombstones and epitaphs. A late-Meiji guide to the city lists 132 temples in Asakusa Ward and 86 in Shitaya. Temple lands shrank greatly, however, as the region became a part of the main Low City, and the pressure on lands near the center of the city led to the closing and removal of cemeteries.

Along towards mid-Meiji the metropolitan government embarked upon the creation of an early version of the public mall or shopping center. On land that had been occupied chiefly by chapels in attendance upon the Kannon, the city built two rows of brick shops, forming a lane from the horse trolley to the south or main front of the grand hall. The city retained ownership and rented the shops. The original buildings were casualties of the earthquake, but the prospect today is similar to that of 1885, when construction was finished. It is not displeasing. Though no longer Meiji it rather looks it, and is perhaps somewhat reminiscent as well of the Ginza Bricktown. From late Meiji into Taishō there had grown up what sons of Edo called the new Asakusa, generally to the south and west of the Kannon. Then came the earthquake, to destroy almost everything save the Kannon itself, and afterwards, those same sons inform us, the new quite took over.

“The word Asakusa,” said Akutagawa, who grew up in Honjo, across the river, “first calls to mind the vermilion hall of the temple—or the complex centered upon the hall, with the flanking pagoda and gate. We may be thankful that they came through the recent earthquake and fire. Now, as always at this season, droves of pigeons will be describing a great circle around the bright gold of the gingko, with that great screen of vermilion spread out behind it. Then there comes to mind the lake and the little pleasure stalls, all of them reduced to cinders after the earthquake. The third Asakusa is a modest part of the old Low City. Hanakawado, Sanya, Komagata, Kuramae—and several other districts would do as well. Tiled roofs after a rain, unlighted votive lanterns, pots of morning glories, now withered. This too, all of it, was left a charred waste.”

The pleasure stalls, said Kubota Mantarō, “are the heart of the new Asakusa, Asakusa as it now will be”:

This Asakusa took the recent disaster in its stride…

But the other, the old Asakusa.

Let the reader come with me—it will not take long—to the top of Matsuchi Hill… We will look northwards through the trees, towards the Sanya Canal. The color of the stagnant water, now as long ago, is like blackened teeth; but how are we to describe the emptiness that stretches on beyond the canal and the cemetery just to the north, and on through mists to the fuel tanks of Senjū, under a gray sky? The little bell tower of the Keiyōji Temple, a curious survivor, and the glowing branches of the gingkos, and the Sanya Elementary School, hastily rebuilt, and nothing else, all the way north, to catch the eye.

Let us go down the hill and cross Imado Bridge… No suggestion remains of the old air, the old fragrance, not the earthen godown remembered from long ago, not the darkly spiked wooden fence, not the willow at the corner of the restaurant. In front of the new shacks … a wanton profusion of hollyhocks and cosmos and black-eyed susans, in a dreariness quite unchanged since the earthquake.

It is the common view, and in the years just after the earthquake, when these melancholy impressions were set down, almost anyone would have thought that the old Asakusa was gone forever, and that “the new Asakusa,” represented by the flashiness of the park and its entertainments, had emerged dominant. In recent years there has been a reversal. The life of the park has been drained away by the new entertainment centers elsewhere, and to the north and east of the temple are still to be found little pockets answering well to Akutagawa’s description of the old Asakusa. Not having flourished, certain back streets had no very striking eminence to descend from.

The novelist Kawabata Yasunari used to say that, though he found abundant sadness in the culture of the Orient, he had never come upon the bleakness that he sensed in the West. Doubtless he spoke the truth. Tanizaki remarked upon the diaspora to the suburbs and beyond of the children of the Low City. He too spoke the truth. Not many residents of Asakusa were born there, and still fewer can claim grandparents who were born there. One may be sad that life has departed the place, but one does not reject Asakusa. There is still something down-to-earth and carpe-diem about it that is not to be found in the humming centers of the High City, or in the stylish, affluent suburbs.

Shitaya and Kanda wards, to the west of Asakusa, were partly flat and partly hilly—partly of the Low City and partly of the High. The Shitaya Ward of Meiji contained both the old Shitaya, “the valley below,” and Ueno, “the upland stretches.” Lowland Shitaya, generally south and east of “the mountain,” Ueno Park, was almost completely destroyed in the fires of 1923. The hilly regions of the park and beyond were spared. At the end of Edo the merchant and artisan classes possessed very little of even the flat portion of Shitaya—a cluster south of the great Kaneiji Temple, now the park, a corridor leading south along the main street to Kanda and Nihombashi, and little more. Almost everything else belonged to the aristocracy and the bureaucracy. Like the busiest part of Asakusa, the busiest part of Shitaya—the “broad alley” south of the mountain and its temple—was a plebeian island largely cut off from the main Low City.

By the end of Meiji the upper classes had for the most part moved west, and their gardens had been taken over by small shops and dwellings, a solid expanse of them from the Hongō and Kanda hills to the river. A brief account in the 1907 guide put out by the city suggests the sort of thing that happened.

Shitaya Park. Situated in the eastern part of the ward. To the east it borders on Samisen Pond and Asakusa Ward, and to the north on Nishimachi, Shitaya Ward. It was designated a park in April, 1890, and has an area of 16,432 tsubo. Once an estate of Lord Satake, it returned to nature with the dismemberment of the buildings, and came to be known popularly as Satake Meadow. It presently became a center for theaters, variety halls, sideshows, and the like, and, as they were gradually moved elsewhere, was assimilated into the city. It may no longer be said to have the attributes of a park.

There is no trace of a park in the district today. The expression rendered as “assimilated” says more literally that the Satake estate “is entirely machiya,” meaning something like the establishments of tradesmen and artisans. Most of the aristocratic lands of Shitaya became machiya without passing through the transitional stages.

Northern Shitaya, near the city limits, was a region of temples and cemeteries, a part of the band streching all along the northern fringes of Edo. A part of Yanaka, north of Ueno, where the last shogun is buried and where also the last poem of Takahashi O-den may be read upon her tombstone, became the largest public cemetery of Meiji. The city has sprawled vastly to the south and west, and today almost anyone from southerly and westerly regions, glancing at a map, forms an immediate and unshakable opinion that anything so far to the north and the east must be of the Low City. In fact it was the new High City of Meiji. As temple lands dwindled it became an intellectual sort of place, much favored by professors, writers, and artists. There is cause all the same, aside from its place on the map, for thinking that it gradually slid into the Low City. Professional keeners for dead Edo would have us believe that what was not lost in 1923 went in 1945, and that most things were lost on both occasions. In fact the Yanaka district came through the two disasters well. Its most conspicuous monument, the pagoda of the Tennōji Temple, was lost more recently. An arsonist set fire to it one summer evening in 1957. The heart of the old Low City contained few temples and Yanaka still contains many. With its latticed fronts, its tiled roofs, and its tiny expanses of greenery, it is the most extensive part of the present city in which something like the mood of the old Low City is still to be sensed.

The Negishi district, east of Yanaka, gave its name to a major school of Meiji poetry. It had long been recommended for the wabizumai, the life of solitude and contemplation, especially for the aged and affluent, and had had its artistic and literary day as well. A famous group of roisterers known as “the Shitaya gang” had its best parties in Negishi and included some of the most famous painters and writers of the early nineteenth century. Like Yanaka in the hills and over beyond the railway tracks, Negishi still has lanes and alleys that answer well to descriptions of the old Low City, but it has rather lost class. No artistic or intellectual person, unless perhaps a teacher of traditional music, would think of living there. It is not a good address. From Yanaka and Negishi one looked across paddy lands to the Yoshiwara. In late Edo and Meiji the owners of the great Yoshiwara houses had villas there, to which the more privileged of courtesans could withdraw when weary or ill. Nagai Kafū loved Negishi, and especially the houses in which the courtesans had languished.

Always, looking through the fence and the shrubbery at the house next door, he would stand entranced, brought to his senses only by the stinging of the mosquitoes, at how much the scene before him was like an illustration for an old love story: the gate of woven twigs, the pine branches trailing down over the ponei, the house itself. Long unoccupied, it had once been a sort of villa or resthouse for one of the Yoshiwara establishments…. He remembered how, when he was still a child on his mother’s knee, he had heard and felt very sad to hear that one snowy night a courtesan, long in ill health, had died in the house next door, which had accommodated Yoshiwara women since before the Restoration. The old pine, trailing its branches from beside the lake almost to the veranda, made it impossible for him to believe, however many years passed, that the songs about sad Yoshiwara beauties, Urasato and Michitose and the rest, were idle fancies, yarns dreamed up by songwriters. Manners and ways of feeling might become Westernized, but as long as the sound of the temple bell in the short summer night remained, and the Milky Way in the clear autumn sky, and the trees and grasses peculiar to the land—as long as these remained, he thought, then somewhere, deep in emotions and ethical systems, there must even today be something of that ancient sadness.

Shitaya Ward, now amalgamated with Asakusa Ward to the east, was shaped like an arrowhead, or, as the Japanese preference for natural imagery would make it, a sagittate leaf. It pointed southwards towards the heart of the Low City, of which it fell slightly short. The character of the ward changed as one moved north to south, becoming little different from the flatlands of Kanda and Asakusa, between which the point of the arrow thrust itself. The erstwhile estates of the aristocracy had been “assimilated,” as the 1907 guide informs us.

Kanda was almost entirely secular. There were Shinto plots, and the only Confucian temple in the city. There were no Buddhist temples at all. The shogunate did not want the smell of them and their funerals so near at hand. The Akihabara district that is now the biggest purveyor of electronic devices in the city took its name from a shrine, the Akiba— “Autumn Leaf.” The extensive shrine grounds, cleared as a firebreak after one of the many great Kanda fires, were Akibagahara, “field of the Akiba.” Then the government railways moved in and made them a freight depot, and the name elided into what it is today. This is the sort of thing that infuriates sons of Edo, and certainly the old name does have about it the feel of the land, and the new one, as Kafū did not tire of saying, has about it the tone of the railway operator. Names are among the things in Tokyo that are not left alone.

The purest of Edo Low City types, popular lore had it, was produced not in the heartland, Nihombashi, but on the fringes. Quarrelsome in rather a more noisy than violent way, cheerful, open, spendthrift, he was born in Shiba on the south and reared in Kanda. It was of course in the Kanda flatlands that he was reared, with the Kanda Shrine (see page 141) to watch over him. (Like Shitaya, Kanda was part hilly and part flat.) Kanda had once been a raucous sort of place, famous for its dashing gangsters and the “hot-water women” of its bathhouses, but in Meiji it was more sober and industrious than the flatlands of Shitaya and Asakusa, nearer the river.

The liveliest spot in Kanda was probably its fruit-and-vegetable market, the largest in the city, official provisioner to Lord Tokugawa himself. Though not directly threatened by the forces of Civilization and Enlightenment, as the fish market was, the produce market of Kanda yet lived through Meiji with a certain insecurity. In the end a tidying-up was deemed adequate, and the produce market escaped being uprooted like the fish market. The big markets were where the less affluent merchant of the Low City was seen at his most garrulous and energetic. The produce market, less striking to the senses than the fish market but no less robust, is a good symbol of flatland Kanda and its Edo types.

The western or hilly part of Kanda was the epitome of the high-collar. There it was that Hasegawa Shigure, child of Nihombashi, had her first taste of the new enlightenment (see page 194). Hilly Kanda had by the end of Meiji acquired the Russian cathedral, one of the city’s grandest foreign edifices, and it had universities, bookstores, and intellectuals. The Kanda used-book district that is among the wonders of the world was beginning to form in late Meiji, on the main east-west Kanda street, then so narrow that rickshaws could barely pass. Losses in 1923 ran into tens of thousands of volumes.

Kanda had the greatest concentration of private higher education in the city, and indeed in the nation. Three important private universities, Meiji, Chūō, and Nihon, had their campuses in the western part of Kanda Ward—three of five such universities that were situated in Tokyo and might at the end of Meiji have been called important. All three were founded in early and middle Meiji as law schools and had by the end of Meiji diversified themselves to some extent. Law was among the chief intellectual concerns of Meiji. If Western law could be made Japanese and the foreign powers could be shown that extraterritoriality no longer served a purpose, then it might be done away with. The liberal arts did not, at the end of Meiji, have an important place in private education. Meiji University had a school of literature, one among four. Nihon had several foreign-language departments, while Chūō had only two branches, law and economics. The liberal arts and the physical sciences were for the most part left to public universities. In Kanda professional and commercial subjects prevailed. This seems appropriate, up here in the hills above the hustlers of the produce market, and perhaps it better represents the new day than does public education. It defines the fields in which the Japanese have genuinely excelled.

The regions east of the river were the saddest victims of Civilization and Enlightenment. This is not to say that they changed most during Meiji—the Marunouchi district east of the palace probably changed more—but that they suffered a drearier change. Someone has to be a victim of an ever grosser national product, and the authorities chose Honjo and Fukagawa wards, along with the southern shores of the bay, after a time of uncertainty in which small factories were put up over most of the city.

It would be easy to say that the poor are always the victims, but the fact is that the wards east of the river, and especially Honjo, the northern one, do not look especially poor on maps of late Edo. Had there been a policy of putting the burden on the lower classes, then Nihombashi and Kyōbashi would have been the obvious targets. The eastern wards were chosen not because they were already sullied and impoverished but because they were so watery, and therefore lent themselves so well to cheap transport. They were also relatively open. Many people and houses would have had to be displaced were Nihombashi to turn industrial.

Lumberyards in Kanda, late Meiji

Though more regularly plotted, the Honjo of late Edo resembles the western parts of the High City, plebeian enclaves among aristocratic lands. Wateriest of all, Fukagawa was rather different, especially in its southern reaches. It contained the lumberyards of the city. The lumberyards were of course mercantile, though some of the merchants were wealthy, if not as wealthy as the great ones of Nihombashi. By the end of Meiji the wards east of the river were industrial and far-from-wealthy makers of things that others consumed. Nagai Kafū wrote evocatively of the change. The hero of The River Sumida, returning to Asakusa from a disappointing interview with his uncle, wanders past rank Honjo gardens and moldering Honjo houses, and recognizes among them the settings for the fiction of late Edo, to which he is strongly drawn. In certain essays the laments are for the changes which, in the years of Kafū’s exile overseas, have come upon “Fukagawa of the waters.”

Heavily populated as the city spilled over into the eastern suburbs, Honjo and the northern parts of Fukagawa were but sparsely populated at the beginning of Meiji. Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, who was born in 1892 and spent his boyhood in Honjo, described the loneliness in an essay written after the earthquake and shortly before his suicide.

In the last years of the nineteenth century and the first years of the twentieth, Honjo was not the region of factories that it is today. It was full of stragglers, worn out by two centuries of Edo. There was nothing resembling the great rows of mercantile establishments one sees in Nihombashi and Kyōbashi. In search of an even moderately busy district, one went to the far south of the ward, the approaches to Ryōgoku Bridge….

Corpses made the strongest impression on me in stories I heard of old Honjo, corpses of those who had fallen by the wayside, or hanged themselves, or otherwise disposed of themselves. A corpse would be discovered and put in a cask, and the cask wrapped in straw matting, and set out upon the moors with a white lantern to watch over it. The thought of the white lantern out there among the grasses has in it a certain weird, ominous beauty. In the middle of the night, it was said, the cask would roll over, quite of its own accord. The Honjo of Meiji may have been short on grassy moors, but it still had about it something of the “regions beyond the red line.” And how is it now? A mass of utility poles and shacks, all jammed in together….

My father still thinks he saw an apparition, that night in Fukagawa. It looked like a young warrior, but he insists that it was in fact a fox spirit. Presently it ran off, frightened by the glint of his sword. I do not care whether it was fox or warrior. Each time I hear the story I think what a lonely place the old Fukagawa was.

The “moderately busy” part of Honjo was the vicinity of the Ekōin Temple, at the eastern approaches to Ryōgoku Bridge, one of five put across the Sumida during the Tokugawa Period. The Ekōin was founded to console the victims of the great “fluttering-sleeve” fire of 1657, so called from a belief that it was spread by a burning kimono. It was among the great temples of Edo, though Basil Hall Chamberlain and W. B. Morse thought it less than elevating. They said of it, in the 1903 edition of their guide to Japan, that it “might well be taken as a text by those who denounce heathen temples. Dirty, gaudy…the place lacks even the semblance of sanctity.”

The Ekōin attracted places of refreshment and entertainment, solace to the living as well as the departed, less varied and on the whole shabbier than those of Asakusa. The “broad alley” of Ryōgoku fared badly in Meiji and after. At the end of Edo it was one of the three famous “broad alleys” of the Low City. Ryōgoku continued until the Second World War to be the Sumo center of the land. There it was that the big tournaments were held from late Edo down to the Second World War, but they moved away. The gymnasium was requisitioned by the American Occupation and then sold to a university, and the Sumō center of the city and the nation has for three decades now been on the right bank of the river.

Not much remains at Ryōgoku. It became a commuter point when a railway station was finished in 1903, but a minor one, serving some of the poorest parts of the city and only the Chiba Peninsula beyond. So it may be said that Honjo, once unpeopled, is now crowded and subdued. No part of the city is without its pockets of pleasure and entertainment, but Honjo has none that would take the pleasure-seeker out of his way.

On a single evening every year, something of the old joy and din came back. It was the night of the “river opening,” already described, admired by U. S. and Julia Grant, E. S. Morse, and Clara Whitney, among others. The crowds were so dense at the 1897 opening that the south rail of the bridge gave way, and people drowned.

Still in late Meiji the district from northern Honjo into the northern and eastern suburbs was much recommended for excursions. It enjoyed such excursions in perhaps the greatest variety in all the city, though they were becoming victims of material progress. The 1907 guide put out by the metropolitan government thus describes the state of affairs: “Under the old regime the district was occupied by townsmen and the lower ranks of the aristocracy. It was also the site of the official bamboo and lumberyards. Today it is mostly industrial. To the north, however, is Mukōjima, a most scenic district, and in the suburbs to the east are such attractions as the Sleeping Dragon Plum and the Hagi Temple, for especially pleasant excursions.” The temple survives, but the hagi (Lespedeza bicolor) of autumn does not. Neither do the plum blossoms of spring. Kafū’s description, in The River Sumida, is of joyous springtide, out beyond the blight; but the blight was advancing.

“They who make the count of the famous places of Tokyo,” says the guide a few pages later, “cannot but put a pair of scenic spots, Ueno and Mukōjima, at the head of their lists.”

Cherries had from the seventeenth century lined the left bank of the Sumida, from a point generally opposite Asakusa northwards into the suburbs. Though gnawed at by industrial fumes from late Meiji, they still attracted throngs during their brief period of flowering that were second only to those of Ueno. The Sumida was still clean enough for bathing—or at any rate no one had yet made the discovery that it was not.

Grassy banks led down to the river on the Honjo side, and small houses lined the Asakusa bank, waiting resignedly for the next flood. The river was open, no bridges in sight north from Asakusa, with at least four ferry landings well within sight on either bank. As the city took to wheels, bridges came into demand, but the ferry must have been the pleasanter way to cross, especially in cherry-blossom time. The last of the Sumida ferries, much farther downstream, did not disappear until after the Second World War.

Tokyo is today, and it must have been in late Meiji, a city where one learns to gaze only at the immediate prospect, blotting out what lies beyond. Crossing Azuma Bridge at Asakusa, one would have had to do this, unless a background of chimneys and smoke and utility wires could be regarded as pleasing. Yet the foreground must have been very pleasing indeed.

The view across the Sumida from Honjo to Asakusa was quiet urban harmony, and that in the other direction was pastoral calm, broken by those noisy vernal rites when the cherries were in bloom. In the one direction was the “old Asakusa” of Kubota Mantarō, low wooden buildings at the water’s edge with the sweeping roofs and the pagoda of the Asakusa Kannon beyond, and Matsuchi Hill, the only considerable rise in the Low City, slightly upstream. In the other direction was the Sumida embankment, surmounted by cherry trees that blocked off all but the top portions of the industrially productive regions beyond, still suggesting that over there somewhere a few old gentlemen of taste and leisure might be pursuing one or several of the ways of the brush.

Beyond the city limits on the left bank, in what was to become Mukōjima Ward, was a pleasant little cove much heard of in amorous fiction of late Edo and Meiji. It was watched over by the Shrine of the River God, tutelary to the Sumida, and it was a good place, remote and serene, to take a geisha. No trace of it remains. The Sumida has been rationalized and brought within plain, sensible limits, with a view to flood control.

Honjo in the Great Flood of 1910

Another view of Honjo during the Great Flood

A victim of pollution, Honjo was also subject to natural disasters. It suffered most grievously among all the wards, perhaps, not in terms of property losses but in terms of wounds that did not heal, from the Great Flood of 1910. Most of the wealthy who had maintained villas beside the river withdrew, hastening the end of the northeastern suburbs as a place of tasteful retirement. The flood-control devices of Taishō and since have been very successful, but they have also been somewhat unsightly. It may be that not many in our day would wish to view the sights and smell the smells of the Sumida (and only stuntsters venture to swim in it). Even if the wish were present, it would be frustrated by cement walls.

On maps of Edo, northern Fukagawa, the southern of the two wards east of the river, looks very much like Honjo, but the watery south is different, solidly plebeian, as no part of Honjo is. Across the river from Nihombashi, Fukagawa was nearer the heart of the Low City. Though not among the flourishing geisha quarters of Meiji, Fukagawa did in the course of Meiji get something that was just as good business, the Susaki licensed quarter (see page 181). Fukagawa was among the better heirs to the great tradition of Edo profligacy.

The Susaki quarter did not, like the Yoshiwara, have a round of seasonal observances, but it was at times a place for the whole family to visit. Shown on certain maps from late Edo as tidal marshes, the strand before the Susaki Benten Shrine was rich in shellfish, and clam raking was among the rites of summer. This very ancient shrine had stood on an island long before Fukagawa was reclaimed. All through the Edo centuries it was presided over by the only feminine member of the Seven Deities of Good Luck. So the quarter had an appropriate patroness, well established. In certain respects Susaki was more pleasing to the professional son of Edo than the Yoshiwara. Not so frequently a victim of fire, there in its watery isolation, it was not as quick to become a place of fanciful turrets and polychrome fronts. Indeed it looks rather prim in photographs, easily mistaken, at a slight remove, for the Tsukiji foreign settlement.

The Fukagawa of late Meiji had more bridges than any other ward in the city, a hundred forty of them, including those shared with Honjo and Nihombashi. Only two were of iron, and a hundred twenty-eight were of wood, suggesting that the waterways of Fukagawa still had an antique look about them.

The beginnings of industrialization, as it concerned Tokyo, were at the mouth of the Sumida and along the Shiba coast. The Ishikawajima Shipyards, on the Fukagawa side of the Sumida, may be traced back to public dismay over the Perry landing. A shipbuilding enterprise was established there by the Mito branch of the Tokugawa clan shortly after that event. It followed a common Meiji course from public enterprise to private, making the transition in 1876.

Over large expanses of the ward, however, Kafū’s “Fukagawa or the waters” yet survived, canals smelling of new wood and lined by white godowns. Kafū was not entirely consistent, or perhaps Fukagawa itself was inconsistent, a place of contrasts. On the one hand he deplored the changed Fukagawa which he found on his return from America and France, and on the other he still found refuge there from the cluttered new city (see pages 61-62). His best friend, some years later, fled family and career, and took up residence with a lady not his wife in a Fukagawa tenement row. There he composed haiku. In Fukagawa, said Kafū approvingly, people still honored what the new day called superstitions, and did not read newspapers.

The grounds of the Tomioka Hachiman were in theory a park, one of the original five. Much the smallest, it had a career similar to that of Asakusa. It dwindled and presently lost all resemblance to what is commonly held to be a public park. The Iwasaki estate in Fukagawa, now Kiyosumi Park, is far more parklike today than this earlier park. The history of the two is thus similar to the history of Ueno and Asakusa. It was best, in these early years, to keep the public at some distance from a park. Deeded to the city after the earthquake, Kiyosumi Park was the site of the Taishō emperor’s funeral pavilion. The beauties of the Fukagawa bayshore are described thus in the official guide of 1907:

One stands by the shrine and looks out to sea, and a contrast of blue and white, waves and sails, rises and falls, far into the distance. To the south and east the mountains of the Chiba Peninsula float upon the water, raven and jade. To the west are the white snows of Fuji. In one grand sweep are all the beauties of mountain and sea, in all the seasons. At low tide in the spring, there is the pleasure of “hunting in the tidelands,” as it is called. Young and old, man and woman, they all come out to test their skills at the taking of clams and seaweed.

One senses overstatement, for the guide had its evangelical purposes. Yet it is true that open land and the flowers and grasses and insects and clams of the seasons were to be found at no great distance beyond the river. When, in the Taishō Period, the Arakawa Drainage Channel was dug, much of its course was through farmland.

Among the places for excursions, only the Kameido Tenjin Shrine and its wisteria survive. Waves of blue, mountains of raven and jade, are rarely to be seen, and the Sumida has been walled in. Yet the more remarkable fact may be that something still survives.

There is the mood of the district, more sweetly melancholy, perhaps, for awareness of all the changes, and there are specific, material things as well, such as memorial stones and steles. Some of the temple grounds are forests of stone. Kafū’s maternal grandfather and Narushima Ryūhoku are among those whose accomplishments will not be completely forgotten, for they are recorded upon the stones of Honjo and Mukōjima. The great Bashō had one of his “banana huts” in Fukagawa. It too is memorialized, though finding it takes some perseverance.

A mikoshi (god-seat) at the Fukagawa Hachiman Shrine festival

The other industrial zone was along the bayshore in the southernmost ward, Shiba, which was also the ward of the railroad, the only ward so favored in early Meiji. The Tokyo-Yokohama railroad entered the city at the southern tip of Shiba, hugged the shore and passed over fills, veered somewhat inland, and came to its terminus just short of the border with Kyōbashi. Closely following the old Tōkaidō, it blocked the plebeian view of the bay (or, it might be said, since Meiji so delighted in locomotives, provided new and exciting perspectives). It may or may not be significant that the line turned inland to leave such aristocratic expanses as the Hama Palace with their bayshore frontage.

Shiba at the south and Kanda at the north of the Low City were honored in popular lore as makers of the true child of Edo. The fringes were not as wealthy as the Nihombashi center, and so their sons, less inhibited, had the racy qualities of Edo in greater measure. Most of Shiba is hilly and not much of it was plebeian at the end of Edo. Edo land maps show machiya, “houses of townsmen,” like knots along a string. There was a cluster at the north, around Shimbashi, where the first railway terminus was built, a string southwards to another knot, between the bay and the southern cemetery of the Tokugawa family, and another string southwards to the old Shinagawa post-station, just beyond the Meiji city limits.