HAPPY RECONSTRUCTION DAYS

The official view was that the reconstruction of Tokyo from the great earthquake was complete by 1930. A “reconstruction festival” took place in March of that year. The emperor, who had been regent at the time of the earthquake, was among those who addressed a reconstruction rally in the palace plaza. The mayor addressed a gathering in Hibiya Hall, a few hundred yards to the south. The citizenry was not much a part of these rallies, but the celebrations went on for several days and included events to please everyone—parades and “flower trolleys” and the like. These last were elaborately decorated trolley cars that went all over the city.

The Shōwa emperor, then regent, on an inspection tour after the earthquake; he is standing next to the chair

The emperor took an inspection tour, and expressed taciturn satisfaction with all that he saw by way of reconstruction and hopes for a future of unity and progress. He used the word “capital” to particular effect, as if to emphasize that there was to be no more talk of a capital elsewhere. The organizers of the tour shielded him from the masses with a thoroughness at which the Japanese are very good. Some fifteen thousand people with whom it was conceivable he might come into contact were vaccinated for smallpox. An estimated quarter of a million people were in some way involved in the planning and execution. The tour took him through the flat Low City, the regions most cruelly devastated by earth quake and fire. He stopped, among other places, at Sumida Park and the earthquake memorial (see page 299).

The park is a product of the earthquake, one of the two big new parks beside the Sumida River. It runs for not quite a mile along the right, or Asakusa, bank, less than half that distance along the left bank. The shorter, or left-bank, portion has been the more successful as a park, because it contains venerable religious institutions and the famous line of cherry trees. A new start had to be made on this last. The fires of 1923 destroyed the old one almost completely. Much of the right-bank portion is on reclaimed land. The Arakawa Drainage Channel of mid-Taishō had removed the threat of floods and made reclamation possible. When, in recent years, an ugly concrete wall was put up to contain the river, the incentive was less a fear of waters rushing down the river than of waters rushing up from the bay during stormy high tides. Title to the land for Hamachō Park, the other of the two, on the right bank downstream, presented few difficulties, since there were only three landowners. Getting rid of all the little places that had rights of tenancy was more complicated. Much of the Hamachō geisha district happened to sit upon the tract, and geisha and their patrons can be strong-willed and influential people. The quarter was rebuilt a short distance to the west.

If the official view is accepted, the city did not have long to enjoy its new self. The reconstruction had taken seven years. Only a decade and a little more elapsed before the Second World War started pulling things apart once more. Happy days were few. It may be, indeed, that the years of the reconstruction were happier than the years that followed, for the latter were also the years of the depression, the assassinations, and the beginnings of war.

The Japanese word that is here rendered as “reconstruction” is also rendered by the dictionaries as “restoration.” Perfect restoration of a city is probably impossible. There may be attempts to redo a city exactly as it was before whatever made restoration necessary. There have been such attempts in Europe since 1945. The results may be faithful to all the evidence of what was lost, but they are somehow sterile. The life that produced the original is not there.

Nothing of the sort was attempted in Tokyo. Probably it would have been impossible except in limited neighborhoods. We may be grateful that the city was allowed to live and grow, and not forced back into molds it had outgrown. Yet, though few people now alive are old enough to remember what was there before September 1, 1923, one has trouble believing that the old city was not more pleasing to the eye than what came after. If perfect restoration is probably impossible, a reconstruction is generally less pleasing than what went before it. In Tokyo the reasons are not mysterious. They have to do with the fact that Tokyo and Japan had opened themselves in the decade of the 1860s to a deluge of devices and methods from a very alien culture. These had much to recommend them. They were ways of fending off political encroachment. They also tended to be cheaper and more convenient than old devices and methods. So with each reconstruction jerry-built hybrids became more common.

The citizenry seems on the whole to have been rather pleased with the rebuilding, as it was again to be in 1945 and after. Everything had become so cheerful, all that white concrete replacing all that dark plaster and those even darker tiles. Sukiya Bridge, west of Ginza, with the new Asahi Shimbun building reflected in its dark waters like a big ship, and the Nichigeki, the Japan Theater, like a bullring, was the place where all the mobo and moga, the modern boys and girls (for these expressions see page 324), wanted to have their pictures taken.

Fully aware that there are no rulers for measuring, and at the disadvantage of not having been there, we may ask just how much it did all change. The opinions of the best-informed and most sensitive are not unanimous. Most of what survived from Edo had been in the Low City, because that is where most of Edo was. Therefore most of it disappeared. So much is beyond denying. It is in the matter of the rebuilding and the changes it brought to the physical, material city and to its folkwayschanges in spirit, we might say—that opinion varies.

Kyōbashi, as rebuilt after the earthquake

In the early years of Shōwa, Nagai Kafū was spending many of his evenings in Ginza, at “cafés,” which today would more likely be called bars or cabarets. In 1931 he put some of his experiences and observations into a novel, During the Rains (Tsuyo no Atosaki). An aging character who is in many ways a surrogate for Kafū himself—although Kafū was younger, and never served a prison term for bribery, as the character has—muses upon the Ginza of recent years. Every day something changes; the sum of changes since the earthquake is like a dream. The Ginza of today is not the Ginza of yesterday. The old gentleman’s interests are rather narrow. He is chiefly concerned with the cafés which sprang up in large numbers after the earthquake, most of them on burnt-over tracts, and which, being outposts of the demimonde, were highly sensitive to new fashions and tastes. He speaks for Kafū, however, and Kafū found the changes devastating. The old pleasure centers were gone, and good taste threatened to go with them.

Tanizaki Junichirō, a native of the city who had been away most of the time since the earthquake, felt differently. Change had not lived up to his predictions. On September 1, 1923, he was in the Hakone Mountains, some fifty miles southwest of Tokyo. He had a famous vision of utter destruction and a splendid flapper-age rebuilding. What he saw and wrote of in 1934 was disappointing, or would have been had he still been in his 1923 frame of mind. He had changed, and was glad that changes in the city had not been as extreme as he had hoped and predicted. The Tanizaki of 1934 would have been disappointed, this is to say, if the Tanizaki of 1923 had not himself changed.

So ten years and one have now gone by. The decade which seemed so slow as it passed came to an end on September 1 of last year. I am forty-nine. And how are things today with me, and how are things with Tokyo? People say that the immediate future is dark, and that nothing is as it should be; yet looking back over the meditations in which I was sunk on that mountain road in Hakone, I feel somewhat strange. I do not know whether to be sad or happy at the irony of what has happened. My thoughts then about the extent of the disaster, the damage to the city, and the speed and form of the recovery were half right and half wrong…. Because the damage was less than I imagined, the recovery in ten years, though remarkable, has not been the transformation I looked for. I was one of those who uttered cries of delight at the grand visions of the home minister, Gotō Shimpei. Three billion yen would go into buying up the whole of the burned wastes and making them over into something regular and orderly. They were not realized. The old tangle of Tokyo streets is still very much with us. It is true that large numbers of new bridges, large and small, now describe their graceful arcs over the Sumida and other rivers and canals. The region from Marunouchi through Ginza and Kyōbashi to Nihombashi has taken on a new face. Looking from the train window as the train moves through the southern parts of the city and on past Shimbashi to the central station, I cannot but be astonished that these were lonely wastes where I would play half a day as a child. People back from abroad say that Tokyo is now a match for the cities of Europe and America…. The daydream in which I lost myself on September 1, 1923—I neglected to think even of my unhappy wife and daughter, back in the city—did not approach the imposing beauty I now see before me. But what effect has all this surface change had on the customs, the manners, the words, the acts of the city and its people? The truth is that my imagination got ahead of me. Westernization has not been as I foresaw. To be sure, there have recently appeared such persons as the stick girls of Ginza, and the prosperity of bars and cafés quite overshadows that of the geisha quarters, and movies and reviews are drawing customers away from Kabuki; but none of these places, and even less the casinos and cabarets, bears comparison with even the Carleton Café in Shanghai…. How many women and girls wear Western dress that really passes as Western dress? In summer the number increases somewhat, but in winter you see not one in ten among shoppers and pedestrians. Even among office girls, one in two would be a generous estimate.

(Since Tanizaki was born in 1886, his age is obviously by the Oriental count. “Stick girls” were female gigolos. Like walking sticks, they attached themselves to men, in this case young men strolling in Ginza.)

So Tanizaki’s feelings are mixed. He is sad that he must admit his inadequacies as a prophet and sad too that with regard to Nihombashi, at least (see page 293), his predictions were not exaggerated. Yet he does not see changes in customs and manners as Kafū does.

Writing also in the early thirties, Kawabata Yasunari is more interested in physical change, and is a subtler chronicler of it, than Kafū or Tanizaki. (Kafū was twenty years older than Kawabata, Tanizaki thirteen.) In Hama Park he comes upon a kind of revivalism directed not at Edo and the Japanese tradition but at early Westernization. He finds Western tendencies, in other words, that have become thoroughly Japanized.

Everything is new, of course, Hama Park being one of the two new ones along the banks of the Sumida. Nothing is unchanged except the sea gulls and the smell of the water. Yet nostalgia hangs over the place. The new Venetian pavilion is meant to recall a famous Meiji building lost in the earthquake, the offices put up by Josiah Conder for the Hokkaido Development Bureau. Conder, an Englishman, was the most famous of foreign architects active in Meiji Japan. The music and revelry from the riverboats of Edo are too remote for nostalgia.

Kawabata does not tell us what he thinks of Sumida Park, the other new riverside one, but quotes a friend who is an unreserved booster. With its clean flowing waters and its open view off to Mount Tsukuba, Sumida Park, says the acquaintance, is the equal of the great parks beside the Potomac, the Thames, the Danube, the Isar (which flows through Munich). Give the cherry trees time to grow and it will be among the finest parks in the world. In his silent response Kawabata is perhaps the better prophet. Tsukuba is now invisible and concrete walls block off the view of a very dirty river. Only in cherry-blossom time do people pay much attention to the park, and even then it is not noticed as is the much older Ueno Park.

Kawabata has a walk down the whole length of the new Shōwa Avenue, from Ueno to Shimbashi. Some liken it to the Champs-Elysèes and Unter den Linden. Kawabata does not. “I saw the pains of Tokyo. I could, if I must, see a brave new departure, but mostly I saw the rawness of the wounds, the weariness, the grim, empty appearance of health.”

Shōwa Avenue (Shōwadōri), looking northwards from the freight yards at Akihabara

Famous old sweets, offered for centuries along the east bank of the Sumida, are now purveyed from concrete shops that look like banks. (Though Kawabata does not mention it, the mall in front of the Asakusa Kannon Temple was also done over in concrete, in another kind of revivalist style, the concrete molded to look like Edo. The main building of the National Museum of Ueno, finished in 1937, is among the most conspicuous examples of the style.) The earthquake memorial on the east bank of the Sumida, where those tens of thousands perished in the fires of 1923, is a most unsuccessful jumble of styles, also in concrete. Is it no longer possible, Kawabata asks of a companion, to put up a building in a pure Japanese style? “But all these American things are Tokyo itself,” replies the companion, a positive thinker. And a bit later: “They may look peculiar now, but we’ll be used to them in ten years or so. They may even turn out to be beautiful.”

Kawabata does think the city justly proud of its new bridges, some four hundred of them. Indeed they seem to be what it is proudest of. In a photographic exhibition about the new Tokyo, he notes, more than half the photographs are of bridges.

In 1923 Tokyo was still what Edo had been, a city of waters. The earthquake demonstrated that it did not have enough bridges. There were only five across the Sumida. They all had wooden floors, and all caught fire. That is why more people died from drowning, probably, than directly from the earthquake. On the eve of Pearl Harbor, with the completion of Kachitoki Bridge, there were eleven. Kachitoki means “shout of triumph,” but the name is not, perhaps, quite as jingoistic as it may seem. Those who chose it in 1940 may well have had in mind the shout of triumph that was to announce a pleasant end to the unpleasantness on the continent, but the direct reference is to a triumph that actually came off, that over the Russians in 1905. The name was given to a ferry established that year between Tsukiji and filled lands beyond one of the mouths of the Sumida. The name of the ferry became the name of the bridge, a drawbridge that was last drawn almost twenty years ago. By the late fifties automobile traffic to and from Ginza was so heavy that there was congestion for two hours after a drawing of the bridge.

Nor were there enough bridges across the Kanda River and the downtown canals. These waterways did not claim the victims that the Sumida did, but they were obstacles to crowds pressing toward the palace plaza. Of the streets leading westward from Ginza toward the plaza and Hibiya Park, only three had bridges crossing the outer moat. The moat was now bridged on all the east-west streets, as also was the canal that bounded Ginza on the east.

Moat and canal now are gone. There was some filling in of canals from late Meiji, as the city turned from boats to wheels for pleasure and for commerce. Between the earthquake and the war several canals in Nihombashi and Kyōbashi were lost, but one important canal was actually dug, joining two older canals for commercial purposes. Other canals were widened and deepened. Both in 1923 and in 1945 canals were used to dispose of rubble, that reconstruction might proceed. It has been mostly since 1945 that Tokyo of the waters has been obliterated. In the old Low City the Sumida remains, and such rivers or canals as the Kanda and the Nihombashi, but the flatlands are now dotted with bus stops carrying the names of bridges of which no trace remains. Venice would not be Venice if its canals were filled in. Tokyo, with so many of its canals turned into freeways, is not Edo.

It was after the earthquake that retail merchandising, a handy if rough measure of change, went the whole distance toward becoming what the Japanese had observed in New York and London. Indeed it went further, providing not only merchandise but entertainment and culture. Mitsukoshi, one of the bold pioneers in making the dry-goods stores over into department stores selling almost everything, has had a theater since its post-earthquake rebuilding. Most department stores have had amusement parks on their roofs and some still have them, and all the big ones have gardens and terraces, galleries and exhibition halls.

The great revolution occurred at about the turn of the century, when Mitsukoshi and the other Nihombashi pioneer, Shirokiya, started diversifying themselves. What happened after the earthquake is modest by comparison, but a step that now seems obvious had the effect of inviting everyone in. Everyone came.

The change had to do with footwear, always a matter of concern in a land whose houses merge indoors and outdoors except at the entranceway, beyond which outdoor footwear may not pass. Down to the earthquake the department stores respected the taboo. Footwear was checked and slippers were provided for use within the stores. There were famous snarls. They worked to the advantage of smaller shops, where the number of feet was small enough for individual attention. After the earthquake came the simple solution: Let the customer keep his shoes on.

Simple and obvious it may seem today, but it must have taken getting used to. Never before through all the centuries had shod feet ventured beyond the entranceway, or perhaps an earth-floored kitchen.

Smaller shops had to follow along, in modified fashion, if they were to survive. In earlier ages customers had removed their footwear and climbed to the straw-matted platform that was the main part of the store. There they sat and made their decisions. Customer and shopkeeper were both supposed to know what the customer wanted. It was fetched from warehouses. Now the practice came to prevail of having a large part of the stock spread out for review. Floor plans changed accordingly. There was a larger proportion of earthen floor and a smaller proportion of matted platform, and customers tended to do what they do in the West, remain standing and in their shoes or whatever they happened to bring in from the street with them.

Private railways were beginning to put some of their profits from the lucrative commuter business, which in Meiji had been largely a freight and sewage business, into department stores. In this they were anticipated by Osaka. The Hankyu Railway opened the first terminal department store at its Umeda terminus in 1929. Seeing what a good idea this was—having also the main Osaka station of the National Railways, Umeda was the most important transportation center in the Kansai region—the private railways of Tokyo soon began putting up terminal department stores of their own. Thus they promoted the growth of the western transfer points—Shibuya, Shinjuku, and Ikebukuro—and their control over these most profitable of places.

The department stores discontinued old services The bourgeois matron from the High City now had to come to the store. Fewer and fewer stores would come to her, as all of them had in the old days. New services were added as the railways began to open their stores and competition became more intense: free delivery, even free bus service to and from stores. If it asked that the matron set forth and mingle with the lesser orders, the department stove made the pvocess as painless for her as possible.

External architecture changed along with floor plans. Tiled roofs began to disappear behind false fronts. The old shop signs, often abstract and symbolic and always aesthetically pleasing, gave way to signs that announced their business loudly and unequivocally. Advertising was now in full flood. Huge businessman and little businessman alike had taken to it, and the old subdued harmonies of brown and gray surrendered to a cacophony of messages and colors. This seems to have been truer west than east of the Sumida. In the conservative eastern wards rows of blacktiled roofs were still visible from the street. The west bank was said after the earthquake and rebuilding to resemble a river town put up by the Japanese in Manchuria.

The first vending machines were installed at Tokyo and Ueno stations early in 1926. Like advertising, whose origins in Tokugawa and Meiji were so simple that they were almost invisible, vending machines have become an insistent presence in the years since. They now offer an astonishing variety of wares, from contraceptives to a breath of fresh air.

Like the practices and habits of shoppers, those of diners-out changed. The restaurant in which one eats shoeless and on the floor is not uncommon even today. Yet new ways did become common at the center, Ginza, and spread outward. Good manners had required removing wraps upon entering a restaurant, or indeed any interior. Now people were to be seen eating with their coats and shoes on, and some even kept their hats on. Before the earthquake women had disliked eating away from home—it was not good form. The department-store dining room led the way in breaking down this reticence, and the new prominence of the working woman meant that women no longer thought it beneath them to be seen by the whole world eating with other women. Before the earthquake a restaurant operator with two floors at his disposal tended to use the upper one for business and the lower one for living. Now the tendency was to use the street floor for business. An increasing number of shopkeepers (a similar trend in Osaka is documented in Tanizaki’s The Makioka Sisters) used all the floors for business and lived elsewhere, most often in the High City. So it was that money departed the Low City.

The habits and practices of the Buddhist clergy were also changing. The priests of some sects had long married. Now there was an insurgency in a stronghold of Tendai, one of the sects that had remained celibate.

The Kaneiji Temple once occupied most of the land in Shitaya Ward that is now Ueno Park. There it ministered to the souls of six Tokugawa shoguns, whose graves lay within the premises. It was almost completely destroyed in the “Ueno War” of 1868, when the Meiji government subdued the last Tokugawa holdouts in the city. Sorely reduced in scale, the temple was rebuilt and came through the earthquake without serious damage. In the Edo centuries there were fifteen abbots, even as there were fifteen shoguns. All of the abbots were royal princes, and all were celibate, at least to appearances, though dubious teahouses in the districts nearby seem to have catered to the needs of the Kaneiji clergy. In Meiji the abbots started taking common-law wives. In 1932 one of them made bold to enter into a formal, legal marriage. The appointment of his successor was the occasion for a struggle between the Kaneiji and Tendai: headquarters on Mount Hiei, near Kyoto. Hiei demanded that the Kaneiji candidate choose between marriage and career, and did not prevail. He had both. The Hiei abbots have gone on being celibate.

The female work force was expanding rapidly. In that day when Taisho democracy was dying but not quite dead, a few people were beginning to have ideas about the equality of the sexes. Already in Meiji, women had taken over nursing and the telephone exchanges. In the years before and after the change of reigns “red-collar girls” appeared. These were bus conductors, and their trade was almost entirely feminine until its extinction after the Second World War. Up and down Shōwa Avenue, the wide new street cut through from Shimbashi to Ueno after the earthquake, were gas-pump maidens. The day of the pleasure motorist-had come, and pretty maidens urged him to consume. The day of the shop girl had also come. Sales in the old dry-goods stores had been entirely in the hands of shop boys.

The question of the shop girl and whether or not she was ideally liberated added much to the interest of the most famous Tokyo fire between the gigantic ones of 1923 and 1945. The “flowers of Edo,” the conflagrations for which the city had been famous, were not in danger of extinction, but they were becoming less expensive and less dramatic. Firefighting methods improved, the widening of streets provided firebreaks, and, most important, fire-resistant materials were replacing the old boards and shingles. Except for the disasters of 1923 and 1945, there have since the end of Meiji been no fires of the good old type, taking away buildings by the thousands and tens of thousands within a few hours. The number of fires did not fall remarkably, but losses, with the two great exceptions, were kept to a few thousand buildings per year.

The famous fire of early Shōwa occurred in a department store. It affected only the one building and the loss of life did not bear comparison with that from the two disasters. It was, however, the first multiple story fire the city had known, and the worst department-store fire anywhere since one in Budapest late in the nineteenth century.

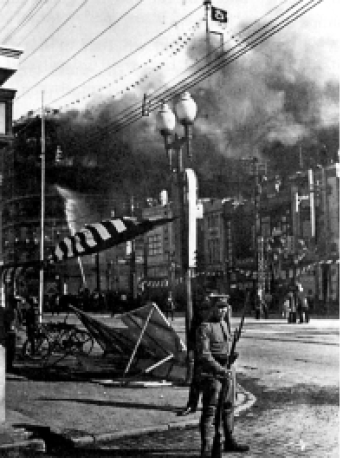

The Shirokiya fire

The Shirokiya, an eight-story building constructed after the earthquake, was the chief rival of the Mitsukoshi through the years of diversifying and expanding. On the morning of December 16, 1932, a fire broke out in the toy department on the fourth floor. The end of the year had traditionally been a time of giving gifts, and Christmas gifts had of recent years been added to those based on older customs. The Taishō emperor brought Christmas Day into prominence by dying on it. Christmas Eve was now becoming what New Year’s Eve is in the West. The Shirokiya was bright with decorations. A technician was repairing Christmas lights and a tree caught fire. The fire spread to the celluloid toys, and the whole fourth floor was soon engulfed. Fortunately this happened at a few minutes after nine, before the store had filled with customers. A watcher from a fire tower nearby saw the fire before it was reported. Firemen were changing shifts, and both shifts rushed to the scene. Presently every pump in the city was on hand. Not much could be done to contain the fire. The floors of the Shirokiya were highly inflammable and all the top ones were quickly in flames. The fire was extinguished a few minutes before noon.

Utility poles and wires along the main streets, and the narrowness of side streets, made it difficult to use ladders, though some rescues were effected. Ropes and improvised lines from kimono fabrics in the store inventories brought people down and slings up to bring more people down. Army planes came by with ropes, although, according to the fire department, they were too late to do much good. It may be that no one except a single victim of asphyxiation need have died. The other thirteen; deaths were by jumping and falling. The bears and monkeys on the roof came through uninjured, to demonstrate that the roof was safe enough-throughout. The jumping was of course from panic. The falling had more subtle causes, having to do with customs and manners—in this instance, the slowness of women in converting to imported dress.

All shop girls in those days wore Japanese dress and underdress, wraparound skirts in various numbers depending on the season. Traditional dress for women included nothing by way of shaped, tight fitting undergarments to contain the private parts snugly. The older ones among the Shirokiya women also being bolder, made it safely down the ropes. Some of the younger ones used a hand for the rope and a hand to keep their skirts from flying into disarray. So they fell. In 1933 the Shirokiya started paying its girls subsidies for wearing foreign dress, and required that they wear underpants.

From about the time of the earthquake, advertising men had been pushing Western underdress for women, which they made a symbol of sexual equality. But a disaster like the Shirokiya fire was needed to effect decisive change. It demonstrated that women were still lamentably backward, and the newspapers loved it. Underpants became one of their favorite causes and enjoyed quick success, though the reform would actually seem to have begun earlier. Kawabata noted that all the little girls sliding down the slides in Hama Park were wearing underpants.

Some years earlier another department store, the new Matsuya in Ginza, which was to be the Central PX for the American Occupation, had provided the setting for another new event. The Shirokiya had the first modern high-rise fire, and the Matsuya the first high-rise suicide. It occurred on May 9, 1926. In a land in which, ever since statistics have been kept, there has been a high incidence of suicide among the young, suicides have shown a tendency toward the faddish and voguish. Meiji had suicides by jumping over waterfalls, and the closing months of Taishō a flurry of jumping from high buildings.

In May 1932 a Keiō University student and his girlfriend, not allowed to marry, killed themselves on a mountain in Oiso, southwest of Tokyo. The incident became a movie, Love Consummated in Heaven, and the inspiration for a popular song.

With you the bride of another,

How will I live? How can I live?

I too will go. There where Mother is,

There beside her,

I will take your hand.

God alone knows

That our love has been pure.

We die, and in paradise,

I will be your bride.

At least twenty other couples killed themselves on the same spot during the same year.

Early in 1933 a girl student from Tokyo jumped into a volcanic crater on Oshima, largest of the Izu Islands. Situated in and beyond Sagami Bay, south of Tokyo, the islands are a part of Tokyo Prefecture. The girl took along a friend to attest to the act and inform the world of it. A vogue for jumping into the same crater began. By the end of the year almost a thousand people, four-fifths of them young men, had jumped into it. Six people jumped in on a single day in May, and on a day in July four boys jumped in one after another.

On April 30 two Tokyo reporters wearing gas masks and fire suits descended into the crater by rope ladders strengthened with metal. One reached a depth of more than a hundred feet before falling rocks compelled him to climb back up again. They found no bodies. After more elaborate preparations the Yomiuri sent a reporter and a photographer into the crater a month later. Using a gondola lowered by a crane, they descended more than a thousand feet to the crater floor. There they found the body of a teenage boy.