Introduction

Dante as Poet, Prophet, and Exile

Dante’s Cathedral: Reading the Comedy on Multiple Levels

The Comedy (Divine Comedy is a title created by Dante’s Renaissance admirers) is the greatest work by the Florentine poet Dante Alighieri (1265–1321)—some would say the greatest work of the Western imagination.1 Whether or not this is true, Dante indubitably keeps company with Homer, Virgil, Sophocles, Shakespeare, and Dostoyevsky. And yet, although the Comedy is an undisputed masterpiece, it has a peculiar medieval flavor to it, which makes it taste quite different from a Homeric epic, a tragedy for the stage, or a realistic novel. And this strong medieval flavor can sometimes spoil our appreciation. I have had students confess to me that they had eagerly looked forward to the Comedy, but when they actually got to it, they were put off by the work’s difficulty and confused by its poetic form. I would like, then, to mention some of the obstacles that the Comedy’s medieval form poses to first-time readers.

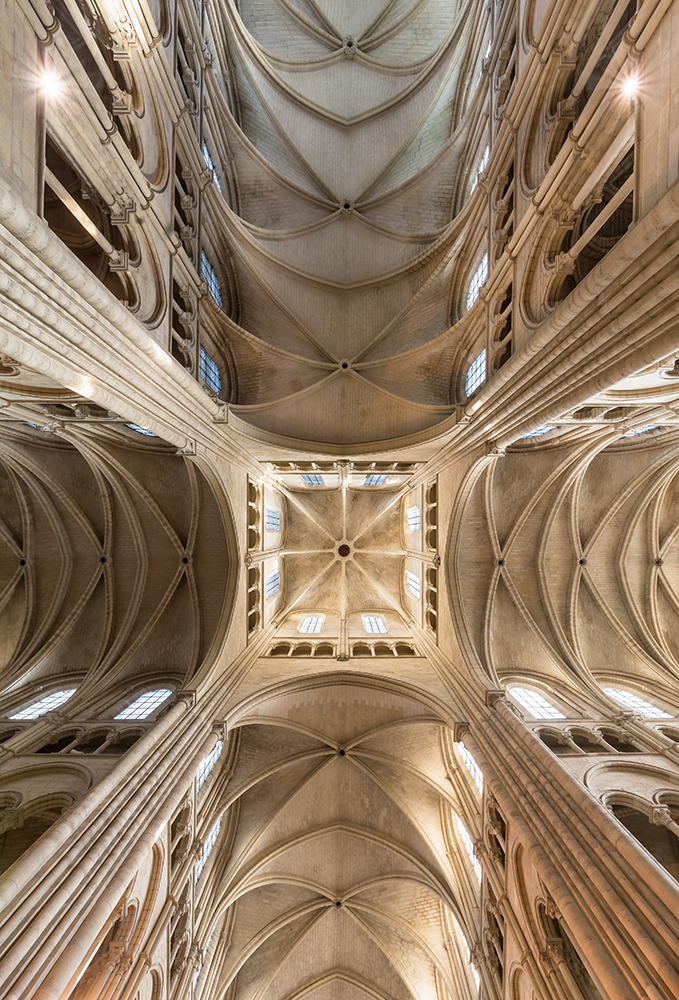

More than once, the Comedy has been likened to a medieval cathedral.2 If you’ve ever stepped into an old-world Gothic cathedral, then you know that the vault soars overhead, rising sometimes to 150 feet, and that everywhere you look your eye finds harmony and graceful order. Medieval cathedrals have a sweeping grandeur as well as an all-encompassing design: every part has a place, and every part has a corresponding part across the aisle. The face of the church, the façade, is divided into hierarchical layers and orderly portals.3 In a similar way, Dante’s poem is famous for its architectural order.

Figure 1. The vault of the Laon Cathedral. [Uoaei1 CC BY-SA 4.0 / Wikimedia Commons]

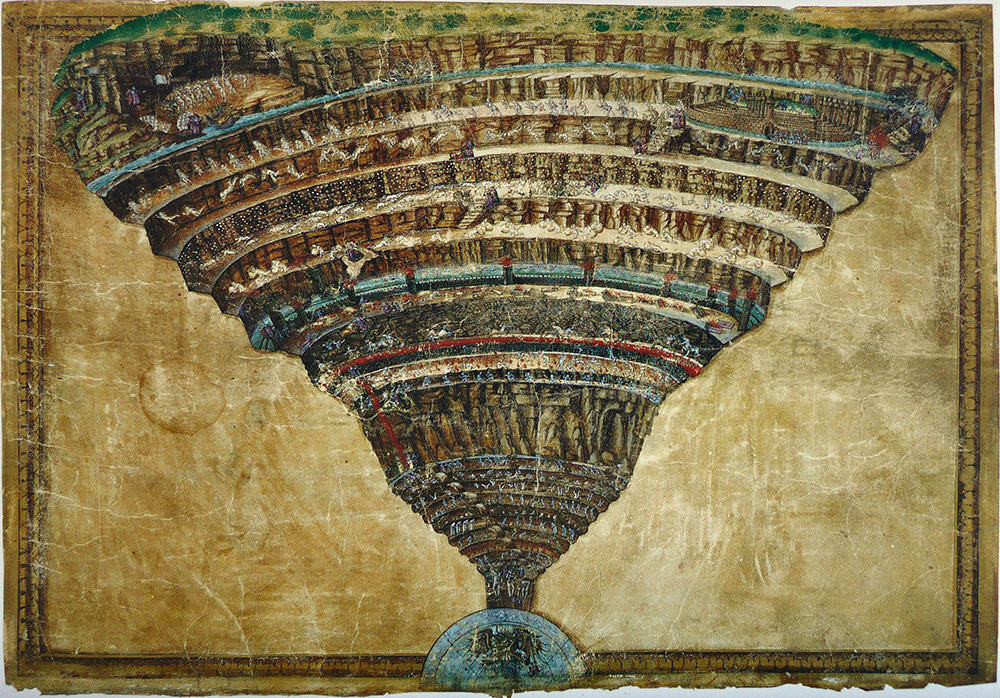

At the most basic level, the Comedy relates the story of a man lost in a dark wood and saved by the ancient Roman poet Virgil, who had been commissioned by a whole hierarchy of saints. The pilgrim—Dante himself—travels through hell, climbs the mountain of purgatory, and rises through the spheres of heaven on his way to see (and be seen by) God. All of these realms and landscapes through which the pilgrim passes are neatly ordered. Each terrace or descending level corresponds to and gives flesh to the moral philosophical principles of Dante’s day.4 In fact, one of the great readers of Dante in our time, Roberto Antonelli, has argued that Dante had the basic blueprint of the whole work in his mind even before he began writing!5 The poet spent almost fifteen years working on the poem, but he was able to write lines for Inferno that would anticipate verses he would write over a decade later for Paradiso, because he had a framework for his imaginative world provided to him by the moral philosophy of his day. It is this palpable and concrete architecture of the afterlife that Florentine artists for centuries after Dante loved to try to map out as accurately as they could.6

Figure 2. Botticelli’s Map of Hell (1480–95). [Public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

But it’s not just Dante’s imaginary landscape of the afterlife that is so well ordered; Dante also meticulously crafted the formal structure of his poem. After the gripping first canto of the Comedy, thirty-three more canti come in Inferno; we then get thirty-three more for Purgatorio, and the same number for Paradiso, for a total of three sets of thirty-three “little songs” (canti) plus an introductory canto, adding up to a perfect one hundred. It’s not just the number of canticles (three) and canti (one hundred) that displays Dante’s obsession with the harmonic perfection of his formal craft, though; he also used a complex and fascinating rhyme scheme, the so-called terza rima (which English translators after Dorothy Sayers do not try to reproduce). What you will see if you look at the Italian page are groups of three-line stanzas (each known as a terzina). The first line of the terzina rhymes with the third line: vita in Inferno 1.1 rhymes with smarrita (Inf. 1.3). The middle line of the terzina introduces a new rhyme, which will be repeated twice in the following terzina: thus, oscura (1.2) / dura (1.4) / paura (1.6). But then at the end of 1.5, we have a new rhyme (namely, forte), which will again be repeated at the end of verse 7 (morte) and verse 9 (scorte). The rhyme scheme, then, is a/b/a, b/c/b, c/d/c, in which the unrhymed word in the middle line of each terzina becomes the outside rhymes in the following terzina. This forms a chain of rhymes, in which each terzina is linked to the previous and following stanzas. Thus, from the very beginning of the poem we have stepped into a world of extraordinary mathematical beauty. All of the drama, all of the action to come, all of the individual personalities will unfold in the midst of this linguistic world, regulated by patterns of threes and tens. For Dante, this order was a clear and evocative sign of the Trinity. God is, as it were, everywhere present within the literary cosmos of the poem.7

The action unfolds not just within sacred space but also within sacred time. Through his periphrastic allusions, Dante establishes with exactitude when his journey takes place. His descent into hell begins precisely on Good Friday, 1300, and continues until he arrives on the shores of Mount Purgatory at dawn, Easter Sunday. The pilgrim will spend three nights in purgatory until he rises to see the souls of heaven. In the very liturgical season in which the medieval church celebrated Christ’s descent into hell and resurrection as a pattern for the Christian life, so too does the pilgrim—seemingly not entirely aware of the sacred time in which he moves—undertake his own journey of descent and rising to renewed life.8 Thus, the pilgrim passes through an imaginary landscape mapped out into dozens of distinct regions, terraces, and circles, on a journey divided into distinct phases that have been carefully synchronized with liturgical time. And the poet narrates each step of this journey in particular canti, all of which have a specific place carefully assigned to them within the numerical ordering of the poem. Indeed, Dante’s world is so architectural that the Comedy has been called “the last Gothic Cathedral.”9

And yet there is more to a medieval cathedral than its geometrical order. Indeed, over the walls, ceilings, and floors we can watch a riotous variety of forms at play within the sober, governing architectural patterns: carved stones (of saints, flora, and fauna), interlacing rib vaults, bundles of differently sized stone columns, ornate friezes, windows of different sizes, polychromatic stained glass, and intricate patterns laid into marble floors.10 Analogously, the pilgrim does not just journey from region to region but holds conversations with a bewildering number of very particular, very different, historical and mythological people. And so, in addition to the well-ordered architectural space, all readers of the Comedy are struck—perhaps even overwhelmed and confused—by the poem’s extraordinary abundance. In fact, there are nearly 1,500 proper names throughout the Comedy: names of rivers in obscure parts of Italy; names of geographical regions (woods, mountains, cities, neighborhoods) from history and mythology; classical heroes; mythological beasts; and a host of medieval Florentines (Guido Cavalcanti, Brunetto Latini, Pier della Vigna, Guido da Montefeltro, Cacciaguida, and on and on). Dante intentionally employs a huge cast of characters, drawn from every era of history, right back to Adam and the biblical patriarchs and up to Dante’s contemporary Italy. There are 210 characters who make an appearance in Inferno alone! Try to imagine a play or a film that contained so many actors.11

Both Dante’s Comedy and the medieval cathedral, then, are constructed analogously to the cosmos created by God. On the one hand, you have constellations, stars, and seasons that move in recurring patterns; you have seas and oceans and continents that stay put within their assigned boundaries. On the other hand, you have millions of unique faces, people, minds, languages, and local histories that live and die within the midst of that governing architecture of time and space. Even though I said that Dante stands in the company of Shakespeare, Dostoyevsky, and Homer, it’s understandable why he’s difficult to get into.

This rich complexity, which calls forth such ardent admiration, can also account for why this poem is so difficult to appreciate on a first or even second read. It is also for this reason that this book has been written: to build a bridge from where we are, over the difficulties, so that we can enter into the poem with greater appreciation. In chapter 1, I will talk about how Dante zooms out to give his readers a view of the architectural whole (using a kind of poetic telescope), but only after he has zoomed in to give a close-up of particular human beings (a literary microscope). In the remainder of this introduction, though, I want to explore how these key features of the poem have their roots in the author’s biography. In particular, I will focus on two major moments in Dante’s life: his early love poetry (produced when he was in his twenties) and his failure in politics (the experience of his early thirties). Both of these experiences shaped the horizons for the book he would later write.

Dante before the Dark Wood (1): Love Poet

Dante was born into a minor aristocratic family.12 Scholars think that in the early 1280s—that is, when Dante was the equivalent of a freshman in college—he began to write his first poems, which he deferentially sent around to the established poets of Florence. These poems were not like the poetry he would later write in the Comedy—that is, they were not narrative poems but rather sonnets or canzoni (“little songs” of around one hundred verses). All of Dante’s youthful poems dealt, in one form or another, with falling in love, being in love, suffering when the one you love doesn’t return your love, and so forth. The young poet’s short, powerful, melodious verses quickly gained the admiration of the aristocratic, practicing poets of Florence.

Of course, we all know something about the experience of love: those first exciting and awkward moments when you were attracted to someone and that person was attracted to you (or not); how you worried and talked endlessly about it to anyone who was interested (or even to those who weren’t); the pain of being dumped. Similarly, medieval love poets for centuries before Dante had written about these things, but they had also tried to get all of these phases and elements of the experience of love down to a precise, poetic science.13 Each lyric poet had his trademark specialty. Some wrote on the pain of love (e.g., Guido Cavalcanti); Guinizelli specialized in praise of beauty. But all these “faithful servants of love” (fideli d’amore) agreed that the experience of love, even when one of sweetness, is so psychologically intense that it can best be described in terms of violence: it is an aching or longing that is so passionate it threatens death; it is an arrow that shatters the heart; it is a hurricane gale that breaks a stone tower. The experience of earthly love outweighed any other possible experience; thus, the man or woman in the servitude of love had a quality of “knowledge” higher than that of ordinary existence. In his sonnet “Tanto gentile,” Dante states the ineffability of love concisely: referring to the unspeakable sweetness that comes from Beatrice’s eyes, he says that “none can understand but he who experiences it” (v. 11).14

Although every stage of love is marked by such intensity, it remains true that the experience of unreciprocated love is the most painful experience of all; or, as a friend of Dante’s once put it, “He who loves unloved has the greatest pain; for this pain holds sway over all others and is called the chief one: it is the source of all the suffering that love brings” (Dante da Maiano).15 Thus, love poets also had a particular interest in discovering the mechanics of the process by which one is infected by the contagion of love, because, if you could figure out the physiological process by which you were struck by love, then you could reverse engineer it and make the lady you fell in love with love you in return. The lyric poet thus tried to create a reading experience that would make his reader sigh, weep, feel warmth, and eventually show compassion. The reader is made to enter into the poet’s experience of messiness, confusion, or rage, or of melting, burning, sweetness, and peace. In other words, lyrical poems are “performative”; they are the poet’s tool for creating in you what is happening in me.

By the time he was in his late twenties, Dante had already written several dozen such poems. However, around the year 1293, Dante gathered up thirty-one of these poems and arranged them in a little anthology of his own work. He also did something unprecedented: he added an autobiographical and theological commentary to explain the occasions of the poems and hint at their deeper meaning. He called his work Vita Nuova, or The New Life. The reason this strange, experimental little book (you can read it in under two hours) is so interesting is that it shows Dante’s early desire to elevate a popular form of writing—the vernacular love song—to the level of a theological treatise. Dante did not use the learned language of law, science, or the university (Latin), but rather he took the ordinary language of Italian (although highly stylistically refined) and the common experience of love as the tools for looking for something of that philosophical depth that had largely been the pursuit of the learned, Latinate literary culture.16 And so, the story of how he came to compose these poems takes on powerful overtones.

Dante’s poetic story of his “new life” begins with a description of a childhood experience, in the ninth hour, of the ninth day, of his ninth year, when he first laid eyes on Beatrice. Recalling this event almost eighteen years later, Dante writes:

At that very moment, and I speak the truth, the vital spirit, the one that dwells in the most secret chamber of the heart, began to tremble so violently that even the most minute veins of my body were strangely affected; and trembling, it spoke these words: “Ecce deus fortior me, qui veniens dominabitur michi [Here is a god stronger than I who comes to rule over me].” (Vita Nuova II, 3–4)17

As Dante explains, he knew from that moment that he had been elected the servant of love and that he would remain in servitude forever. There would never be a moment in which he would try not to be in love. In the medieval courtly tradition (for example, in The Romance of the Rose or Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde), the experience of love is as enlivening as it is terrifying. Everything else now seems flat, boring, and dull. In love, you are braver and see the world with a new vigor, but the experience of love can also be extremely dangerous and, as we have seen, painful. For instance, it just so happened that the next time Dante saw Beatrice was exactly nine years later: “She greeted me so miraculously that I seemed at that moment to behold the entire range of possible bliss. . . . I became so ecstatic that, like a drunken man, I turned away from everyone and I sought the loneliness of my room, where I began thinking of this most gracious lady” (III, 5). From then on, Dante nervously anticipated these encounters. When he did see Beatrice, his heart was so full of love that “[he] could not have considered any man [his] enemy” (XI, 16). And yet, at one point in his narration, Dante says that seeing his beloved almost killed him, because as he stared at the miraculous apparition of beauty in front of him, his other vital functions began to fail. Dante plays on the Italian pun of amore (love) and amaro (bitter) to evoke how such intense joy was painful.

And so things might have continued, but Dante, as he relates, had an epiphany, which began the second phase of his “new life.” In the exact middle of Vita Nuova, Dante says he realized that all his previous poetry had merely focused on his response to Beatrice when he received her greeting, but then he “felt forced to find a new theme, one nobler than the last” (XVII, 30). This new theme was not his own suffering and rapturous condition in love but the praise of the beauty of his lady, even if he didn’t feel ready to sing this praise yet. Beatrice was too great for his words at that time, and so he wrote a poem about how he wished he could write an adequate poem. In this famous poem, which will be explicitly cited in the Comedy (“Ladies who have understanding of love”), the young Dante wrote that, wherever his lady goes, “love drives a killing frost into vile hearts / that freezes and destroys what they are thinking; / should one insist on looking at her, / he is changed to something noble or he dies” (XIX, 30). Beatrice, then, is a kind of “burning bush,” an epiphany that causes conversion or freezes the hearts of the wicked on sight.

We can see how Dante is trying to unite the two literary cultures of his day: the secular, chivalric court culture, which wrote about romance and this-worldly love; and the theological and monastic culture, which wrote about a joy you had to wait for. But in the Vita Nuova, Dante is trying to overcome this division, and for this reason his story, although similar to other stories of courtly love, is nevertheless adorned with rich theological language. For example, in his dreams, love speaks to him in Latin, the medieval language of the Bible. Dante calls the times he saw Beatrice on the street not “meetings” but rather Beatrice’s “apparitions” to him. Those moments in which he is caught up and overwhelmed by the strong feelings of love are “transfigurations.” Even Beatrice’s name means “she who Beatifies.” Thus, the poet uses a language steeped in theology to describe his experience of earthly love.

If Dante’s poetic career had ended here, he would be admired, but read only by a few graduate students at an Ivy League university, like any one of his largely forgotten contemporaries (Guido Guinizelli or Guido Cavalcanti). Rather, a disaster took place that changed everything. In the early 1290s (just a few years before Dante began to write the Vita Nuova), the woman he had written about, who he thought was a physical sign of the presence of God in Florence, died; that is, in Dante’s words, Florence was deserted and orphaned of this transcendent beauty. Dante uses the strongest possible language, quoting what the prophet Jeremiah had said about Jerusalem (Lam. 1:1): “How doth the city sit solitary, that was full of people! She that was mistress of the nations is now become as a widow!” (XXVIII, 60). The language is heightened all the more because this text was chanted in the liturgy of Holy Week to describe man’s orphaned state without the presence of Christ!

In the months that followed Beatrice’s death, Dante sought consolation through writing about his grief and, later, in writing love poems to other women (XXXI–XXXIX), but nothing served as an adequate substitute. Dante’s disconsolate “waylessness” continued until, one night, he had a visionary dream in which he saw his soul leave his body, pass through the heavenly spheres, past the stars, until it came to heaven and saw Beatrice among the saints of heaven. There Dante was struck by the radiance of Beatrice, more beautiful now than she had been in life. After relating this extraordinary dream, Dante concludes his Vita Nuova with an exceptional promise that, after a period of intense study, he would write something about Beatrice that no man had ever said about a woman before—or in his words:

After I wrote this sonnet there came to me a miraculous vision in which I saw things that made me resolve to say no more about this blessed one until I would be capable of writing about her in a nobler way. To achieve this I am striving as hard as I can, and this she truly knows. Accordingly, if it be the pleasure of Him through whom all things live that my life continue for a few more years, I hope to write of her that which has never been written of any other woman. (XLII, 86)

It seems clear that this dream is the distant ancestor of what would become the Comedy, although we don’t know what form it would have taken if Dante had had the leisure and libraries of Florence, and the next decade, to work on it. Although it’s fun to speculate about what this poem would have been like (perhaps just a canzone?), it doesn’t matter, because Dante’s goals and plans were rather interrupted.

Dante before the Dark Wood (2): Failed Politician

If Dante spent his early twenties writing love poems, he spent his early thirties as a soldier and a politician in Florence. By the year 1300, Dante’s political career in his republican city was advancing nicely, and had he spent the rest of his life engaged in Florentine political affairs, he never would have made an attempt to fulfill that promise at the end of the Vita Nuova, in which case you would not be reading this book. But something happened to cut Dante’s political career short and make him return to the poetry of his youth. In fact, it was the single worst thing that happened to him after the death of Beatrice: he was exiled from Florence (from wife and children, family, friends, and possessions) by his political enemies, for life. In 1302, while Dante was away on a diplomatic mission, the pro-papal faction seized control of the government (assisted by the politically savvy Pope Boniface VIII) and took their chance to get rid of a number of enemies in the opposing faction. Dante received news on the road that if he returned, he would be executed.

In some ways Dante was the victim of large, powerful, international political movements, which had been grinding against one another for centuries, like two huge tectonic plates. I will try to summarize these world events very quickly, to give a sense of how deep the problem went. After the fall of Rome, the Roman Empire was carved up into little bits, which were managed by local chieftains. And yet, over the next several centuries, these chieftains slowly began to consolidate power, adding surrounding regions to their control through marriage and war, until the point that a descendant of one of these tribes had put together a big chunk of land on the borders of modern France and Germany. His name was Charlemagne. On Christmas Day, 800, he was in Rome, and he was crowned the Roman emperor by Pope Leo III. Then he went back up north of the Alps and continued to rule the newly reconstituted “Roman Empire” from his palace at Aachen. This practice of a German emperor, nominally head of the Roman Empire but ruling from north of the Alps, with exceptions and interruptions continued down to Dante’s day. These Holy Roman emperors, as they were later called, really thought that they were the rightful successors to Caesar Augustus, Trajan, and Constantine, but they remained physically absent from Italy. As a result, the Italian city-states grew accustomed to ruling themselves, and the church, which had to weather centuries of cultural instability, also grew accustomed to being the center of orderly society.

Thus, it is not too great of a surprise that when the Holy Roman emperors began creeping back down into Italy in the 1200s, there was conflict. Frederick II, grandson of Frederick Barbarossa, moved his court to Palermo, Sicily, and thus had a foothold on the Italian peninsula. His illegitimate son, Manfred (mentioned in Purg. 3), tried to continue the legacy of his father. He began moving into central Italy, to bring it under more direct control, but the Italian city-states allied with the pope; together, they in turn invited Charles of Anjou from France to counter Manfred. Manfred was defeated at the battle of Benevento in 1266, the year after Dante was born. Thus, in a way similar to how Southerners for years lived with the memory of the Civil War, even if they had not experienced it, or how my kids know about 9/11, even though they were not alive when it took place, Dante was born into a world that had been shaped by these long-term, international forces that served as a framework even for local politics. Just as politicians of even a small city in the United States will still ally themselves with either Democrats or Republicans, so too did the local political disputes in Dante’s day sort themselves out into factions of imperial supporters (Ghibellines, mainly aristocratic families) and papal supporters (Guelphs, mainly new-moneyed, mercantile families).

What does all of this have to do with Dante? Clearly, Dante became the victim of these old disputes, like one caught up in the middle of some immense, indifferent machine, and his exile was the great unjust calamity of his life. What is extraordinary is that Dante himself later described this disaster as one of the secrets of his success as a poet, because this was the event that transformed him from politician to prophet. Being in political exile meant that he had to become “a party unto himself,” or, in other words, he was forced to leave the polarizing world of politics. He was forced to ask questions not about short-term solutions but about the long-term conditions of why partisanship existed in the first place.18

From Politician to Prophet

Against this background of his exile and early love poetry, we can begin to appreciate the unique intensity of Dante’s great poem, as well as its desire to encompass the totality of the world. If you’ve ever spent a long time away from home in a foreign country, then you know that, even if that place is as delightful as Tuscany, after a while you start aching for home. You miss the effortlessness of life, ease of conversation, shared memories. Similarly, but with much more intensity, Dante ached for home the whole of his adult life. Even years later, when writing the Comedy, Dante had this sorrowful sense of the wayfarer in exile (for example, see Par. 25.1–9). At the same time, though, when Dante returned to writing after his tumultuous political years (1295–1305), he increasingly wanted to fulfill that old promise at the end of the Vita Nuova, the promise to write a love poem that would be greater than anything that had been written before. But now his understanding of love had been forced to get deeper and broader. Now he was writing not for himself and a few Florentine friends but for the world—a world that was so bruised, broken, and divided that it might not even be able to hear a love poem. But what if, just what if, he could write a poem that, by drawing on his own sense of pained exile, could awaken a spiritually sleepy world to what it chooses to forget? What if he could make people feel that they too were in exile, in exile from the Source of Love? What if he could shock, startle, scandalize, and violently shake them wide awake? And then, what if he could give a picture of love that was so beautiful, so stirring, and so deep that they would desire once again to know that love?

Thus, to put it starkly, Dante did not think he was writing literature for entertainment, like a novel, but rather that he was writing a kind of prophetic, visionary treatise—like a Jonah or Jeremiah who came into the city from the desert to rebuke and condemn the inhabitants. His own political exile turned out to be the key to discovering humanity’s spiritual exile. This discovery of spiritual exile, in turn, proved to be the key to writing a vision of love ever so much bigger—indeed, cosmic—than even what he had hoped to undertake at the end of Vita Nuova. To this end, Dante set about to develop a prophetic sensibility, the power to look down into the root causes of society’s problems. And so the wayfarer (the man with the pilgrim’s spirit, who lived his life in longing for home, knowing that he would never return), the politician (who labored for a just society), and the poet (who lost sleep at night in the lovesick effort to get just the right music into his language) united to write an intense and ambitious poem that would transform the world: the Comedy.