2

The Fear of Hell and the Fear of God

(Inferno 3–9)

Entering Hell

For good or ill, by the end of Inferno 2, the journey has been launched. And although the pilgrim will experience doubt on other occasions, he has irreversibly committed himself to Virgil’s guidance. The poet describes the pilgrim as following behind Virgil, literally placing his feet in the footsteps left behind by the Roman poet (Inf. 1.136; 23.147–48). In this way the two wayfarers walk up to the main portal of hell.

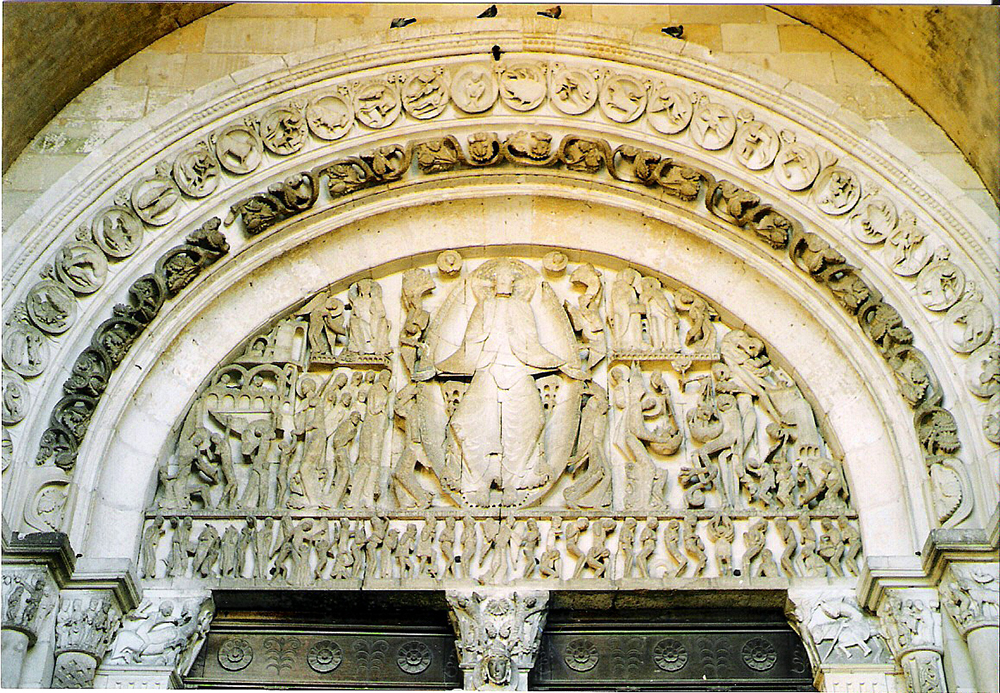

In the Middle Ages, it was common to place an inscription on a gate to a city, to inform travelers who built the arch and for what reason. It was even more common to place an inscription above the grand doors—or portal—of medieval cathedrals, written as if the gate were speaking to the traveler. The inscription would issue some sort of admonition about how to best enter through that portal. One such inscription is above the portal of the Church of St. Lazarus, in Autun, France:

in this way, whoever does not lead a disobedient life will rise again, and endless daylight will shine for him. gislebertus made me. may this terror terrify those whom earthly error binds, for in truth the horror of these sights announces what awaits them.1

Figure 3. The main portal of the Cathedral of St. Lazarus of Autun, France. [Lamettrie CC BY-SA 3.0 / Wikimedia Commons]

The inscription is certainly as frightening as the image, which shows demons weighing souls in scales, avariciously hoping to add to hell. And yet the inscription contains a note of hope. It is a call not to despair but to repentance. The frightening images of demons torturing human beings promotes an interior sense of awe and reverence.

How different is Dante’s portal! The pilgrim pauses to read:

through me one comes into the city of sadness,

through me one comes into eternal sorrow,

through me one comes among the lost people.

justice moved my lofty maker.

divine power made me,

highest wisdom and the first love.

before me there were no created things

except the eternal. i am one that eternally endures.

abandon all hope ye who enter here. (Inf. 3.1–9)

Unlike the portal of a church, this portal to the cathedral of hell promises no redemption; rather, it promises the opposite: “Abandon all hope.” Thus, hell already is a kind of parody of the church: it is a gate that leads nowhere. It does not open up onto a new condition or a new horizon or offer new hope.

It also comes as a bit of a surprise to hear that the gate—and thus all of hell—was made by Power, Wisdom, and Love. In other words, the Trinity, the God who is love, created this place for the eternal punishment of sinners. The God who asks us to hope in him created a place that declares, “Abandon all hope.” This seems to be the difficulty that underlies the pilgrim’s statement “Master, for me their sense is hard” (Inf. 3.12). Virgil, like an exasperated parent who thinks he needs to explain himself again, starts to wind up: “Now it is fitting that all cowardice [viltà] must die” (3.15). In other words, Virgil is giving the same motivational speech he just gave the pilgrim in Inferno 2, but we also might have an interesting example of Virgil’s first small misunderstanding. The reality is that the words are hard for the pilgrim, not because he is suffering from cowardice, but because it is difficult for him, as a Christian, to imagine how this dreary place of darkness was the work of a loving God. The poet does not answer the question now. He leaves it to rub us, like a rock in the shoe.2

Blood, Tears, and Worms

In the second part of Inferno 3, Dante describes the pilgrim’s first reaction to hell proper. Virgil and Dante now take the plunge into infernal darkness, into the midst of “the secret things” of hell (Inf. 3.21). With his sight removed, this is what the pilgrim hears:

Now sighs, laments, and shrill cries

resounded throughout that air without stars.

Yes, I too began to weep as soon as I had entered.

Varied tongues, rough ways of speech,

words of sorrow, shouts of rage, voices,

loud and faint, the sound of hands slapping each other—

jumbled together to make a whirlwind of sound

that spins in a gyre forever in that dark air, devoid of time,

just like the sand spins when gusty wind blows. (Inf. 3.22–30)

The pilgrim breaks down and begins to weep, overwhelmed with fear, confusion, and pity (3.24). He can’t see, and what he hears is a crazy jumble of screaming, shrieking, crying, and cursing, all grunted and shouted in a host of languages, a kind of infernal Babel. Dante tries to get all of this chaos, isolation, pain, and regret into the very acoustics of his language. He carefully chooses harsh, grating words, the kind of verbal equivalent of fingernails scratching on a chalkboard:

Diverse lingue, orribili favelle,

parole di dolore, accenti d’ira,

voci alte e fioche . . . (Inf. 3.25–27)

The poet gives us these visceral words, momentarily, without reference to the pilgrim’s reaction, as if briefly allowing us the opportunity to enter into a first-person experience of the confusion of hell.

Dante soon finds out that the confusing whirlwind of noise is coming from the “pusillanimous,” the small-souled human beings, sometimes called “the indifferent,” who never committed themselves to a course of action, or as Virgil says:

“A miserable fate.

It is endured by those broken souls

who lived without disgrace but without praise. . . .

“They have no hope of death,

and their blind life is so base

that they are envious of every other lot.” (Inf. 3.34–36, 46–48)

Here they bitterly lament their lives, screaming with rage at themselves and everyone else, because they frittered away their precious gift of life to no end. What a contrast to the Florentine poet who spent his whole life as the servant of love, who, as he will later tell us, stayed up late at night and became thin because he was pouring his heart into the writing of the Comedy (see Par. 25.3 and chap. 13 below)!

Both C. S. Lewis and Dorothy Sayers were greatly influenced by this passage. C. S. Lewis once wrote that the opposite of love is not hate but indifference. Similarly, Dorothy Sayers, who translated the Comedy into English in the middle of the twentieth century, wrote a remarkable essay, “The Other Six Deadly Sins” (in Creed or Chaos?), in which I think she had this passage of Dante in mind:

The sixth Deadly Sin is named by the Church Acedia or Sloth. In the world it calls itself Tolerance; but in hell it is called Despair. It is the accomplice of the other sins and their worst punishment. It is the sin which believes in nothing, cares for nothing, seeks to know nothing, interferes with nothing, enjoys nothing, loves nothing, hates nothing, finds purpose in nothing, lives for nothing, and only remains alive because there is nothing it would die for.3

Ouch. Stinging words worthy to be put into the mouth of Virgil!

But to return to Dante. The punishment of such sinners is repulsive. Because they followed nothing on earth, now, in hell, they chase a swiftly moving banner, which races about without ever stopping. It is an empty sign, a meaningless cause, a flag with nothing printed on it (Inf. 3.52). At the same time, the pusillanimous are stung by hornets and wasps, which compel them, against their nature, to keep moving, forcing them into an activity they would not choose on their own, because they had no inner drive and fire to energize them in their lives. Perhaps most tragically, the blood that issues from those welts and the tears that flow from their cheeks mingle and fall to the ground, where the mixture is eaten by nasty worms. In other words, these sinners, who on earth shed no tears and spilled no blood for noble things, here in hell, in a kind of parody of the agony of Christ in the garden, pour forth their vital bodily fluids to be consumed—pointlessly and uselessly—by revolting, slithering insects. This is the first example of that well-known principle of composition Dante followed for creating the vivid landscape of hell: contrapasso (a kind of “counterbalance”). To state it simply, the punishment balances the crime; or, perhaps more accurately, the contrapasso turns the sin inside out to make the full horror of the sin evident for the first time.

On Castles and Heroes (Inferno 4)

In Inferno 4 the pilgrim, after waking up confused and disoriented, carefully creeps toward the edge of the highest ring, leans over, and looks down into a deep abyss (Inf. 4.7–12). In heaven Dante will be surrounded by song, but in hell Dante is completely enveloped by impenetrable darkness and incomprehensible, chaotic sound. The poet who was so sensitive to the musicality of language, who worried about the sound of his words down to the very syllable (as he describes in an early treatise, On Vernacular Eloquence), here uses his poetry to create a murmuring, indistinct roar of darkness. In the following canti, Dante will encounter a series of frightful scenes, one after the other, each of which makes its own dismal addition to this infernal symphony, like a group of instruments in an orchestra each playing its own dreadful song in a different key. But before he moves on, he enjoys one last moment of quiet here in Inferno 4.

The pilgrim is led to a little spot tucked away from the noise. Here he sees the souls of limbo. For the medieval tradition, limbo was the part of hell in which unbaptized babies were lodged, but Dante takes this occasion to exercise some real daring. He adds to this realm another group of souls: the souls of the virtuous pagans, who, as Virgil explains to the pilgrim, are sorrowful, even though they experience no special torment (Inf. 4.28). These noble pagans are here because they, like the infants, were not baptized, given that they were born either before the Christian era or outside of Christian lands, and thus, as Virgil says, “did not worship God correctly” (4.38).

As Dante draws nearer to the center of the castle, wherein these noble souls dwell, a group of poets come forth to celebrate Virgil’s return. This small company is made up of the best poets of all time, whom Dante calls the bella scola (the “beautiful school” of poets). It is made up of Virgil, Homer, the Roman poet Lucan (who was widely read in the Middle Ages, though not now), the Roman poet Horace, and Ovid, the poet who wrote about so many of the mythological transformations of the gods (Metamorphoses). For the medieval mind, these ancient writers were as authoritative as you could get outside the Christian world. These were the poets who understood the secrets of the world, who had profound insights into how to live well, and whose words could inspire imitation. They were also writers unavailable to many medievals because they wrote in the learned language of Latin.4 It is at this point that Dante gives himself an extraordinary compliment and, in doing so, makes an important comment on his goals and ambitions as a vernacular writer. This exclusive group of the best poets of all time warmly welcomes Dante and elects him to become a member of the bella scola: “And even greater honor still they showed: / they made me one in their company. / I was the sixth amidst such wisdom” (Inf. 4.100–102). My students always comment on this line, suggesting that Dante is arrogant. Then Dante follows up that terzina with another:

Thus we went toward the light,

speaking of things of which silence is fitting,

just as in that place speech was due. (Inf. 4.103–5)

This is one of many perplexing instances in which Dante tells us he partook of secret conversations with the ancients, most of which seemingly pertain to the craft of poetry. Throughout the Comedy, Dante likes to portray himself as an apprentice to the old masters, as when, in Purgatorio, the pilgrim will direct his steps to follow the two poets whose talk makes his way easy (Purg. 23.7–9). And thus, although it certainly is the case that Dante Alighieri did not lack self-confidence, beneath that bravado we find a deep reverence for antiquity. Dante really thought that sitting quietly with the old masters could result in wisdom. You could pose questions to them, and then, if you read and studied deeply enough, come to possess their wisdom at least in part, perhaps even becoming worthy of the respect of your heroes. A few decades later, Italian humanists would call this walking “in the footsteps of the ancients,”5 but this knowledge is not easy to win. It’s hard and tedious and slow in coming. Only if you long for it with a burning desire, with unquenchable thirst, only if you fast for it (see Purg. 29.37–42), will you come to it. I think this is why Dante tells us that he won’t tell us, because he is trying to give us that kind of thirst and hunger to look into things deeply—the thirst he himself had.

In the third narrative block of Inferno 4, after he is greeted by the poets of the bella scola, something amazing happens—at least for a medieval intellectual: Dante is escorted across a moat, and then passes through the seven gates of the seven walls of a castle, to arrive at the smooth lawn that forms the courtyard of the castle. And here all the greats of antiquity are assembled. Here is Aristotle, “the master of those who know” (Inf. 4.131), honored by Plato and Socrates; here are the pre-Socratic philosophers (Thales, Heraclitus, and Empedocles). There are Roman thinkers (Cicero and Seneca), as well as the Islamic commentators on Aristotle (Avicenna and Averroës). The great scientists are there, and the great heroes and heroines out of history and old stories: Aeneas, Hector, Julius Caesar, Brutus (the assassin of the tyrant Tarquin who initiated the Roman Republic and refused to be crowned king), Lucretia (who, violated by Tarquin, ended her own life to guard her honor), as well as Camilla, Latinus, and Lavinia (characters from the Aeneid). In other words, the pilgrim has stepped into a library of great books, or rather he’s stepped into those books and now dwells amidst the characters he had spent so long reading about. Here Dante is surrounded by all who thought deeply and originally, who stood courageously in battle, who founded cities, or who so steadfastly committed themselves to some virtue that they became its model and exemplar.

Dante truly believed that these noble souls lived without succumbing to their passions: they were not wrathful, lustful, dishonest, or intemperate. They exercised incredible natural powers of self-control and virtue, and they directed their lives to pursuing justice. For this reason, they do not suffer any direct punishment; their only punishment is the “pain of loss” of the vision of God. They are depicted as having “countenances neither sad nor joyful” (Inf. 4.84), “people” with “grave, slow-moving eyes / and visages of great authority” who “seldom spoke” (4.112–14, trans. Hollander)—serious, good people who don’t waste words and whose inner strength is evident in their commanding visages. And yet, though sober and controlled, they are not happy, let alone joyful, as the saints in paradise will be. In fact, the pilgrim’s first impression of this realm is that the air is continuously stirred by sighs (4.26). Furthermore, Virgil, as he reenters this realm, loses all the color in his face because he returns to a land without hope: “We are lost, and afflicted but in this, / that without hope we live in longing” (4.41–42, trans. Hollander). It is because these souls spent their whole lives pursuing goodness and truth that their sorrow is so intense. They are weighed down by the knowledge that they will never be able to know or taste that ultimate Goodness. It is a dream that will never be fulfilled.

The ancient community of nonbelievers stands in sharp contrast with that other ancient community of biblical patriarchs, who, we learn, once upon a time were also residents in limbo. Within Inferno 4, Dante hesitantly asks Virgil if any soul has ever made it out of this place. Virgil’s response is fascinating: “I was new to this place when I saw / a mighty one come here, crowned in victory. / He dragged out from among us the shade of our first parent, / and the shade of Abel, his son, and that of Noah,” and so on (Inf. 4.52–56). This is the event that you find portrayed on Byzantine icons or in medieval illuminations, in which Christ comes into hell and kicks down the doors, which the devils feebly hold against him. Christ, bursting into hell, grabs the wrists of Adam and Eve and the other patriarchs and energetically pulls them out of limbo. This is the so-called harrowing of hell, which, according to Christian tradition, took place on Holy Saturday, before Christ’s own resurrection—the very event that the liturgy is celebrating while Dante walks through this realm.

Figure 4. A depiction of the harrowing of hell from the Vaux Passional (fifteenth–sixteenth century; artist unknown). [Public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

Thus, the sad, slow, grave souls of the pagans stand in powerful contrast to those biblical souls who also waited, but waited on God with expectancy of deliverance. Virgil’s words are telling: for him, that hero who liberated the souls of the patriarchs was just some possente, some “mighty one,” some generic hero, a Hercules, who from time to time raided hell. But for those who had the eyes to see, who looked to the mountains whence their help came, this was the dawn they had prayed and fasted for; this was the deliverance that they knew they could not provide for themselves.

On the Wings of Doves (Inferno 5)

We now come to one of the most celebrated passages in the Comedy: Dante’s conversation with Francesca da Rimini in Inferno 5.6 From this circle on, all the rest of hell’s inmates suffer not only the pain of the loss of God (like the noble souls in limbo) but also some additional physical torment. When the pilgrim comes into the second circle, he first hears the loud moaning of wind (Inf. 5.29–33) and then sees that here souls are tossed about in these gusts of wind forever. They have lost, as it were, their freedom to move where they wish. In this kind of infernal hurricane, they see a place to which they wish to move and begin moving in that direction, only to be swept off course to some other place. In fact, three times in this canto, Dante uses lovely similes in which he compares these sinners to birds tossed about by strong gusts of wind. My favorite of these similes is the first one, in part because Dante manages to get into his very language the power of the windswept landscape:

And just as wings lift up starlings

in cold weather, in a flock thick and wide,

so did that windy breath carry forth the evil souls.

Hither and thither, now up, now down, it drives them.

No hope comforts them that they will ever find

rest or lesser punishment. (Inf. 5.40–45)

The Italian is evocative: “di qua, di là, di giù, di sù li mena” (5.43). The very sound of the language catches the haphazard movement of the souls, tossed about from here to there.

These souls are, of course, the lustful, and all of the famous lovers of antiquity and the Middle Ages are here: Cleopatra, Helen of Troy, Paris, Tristan, and Dido (from the Aeneid); they are the equivalent of, for us, Romeo and Juliet, Madame Bovary, Anna Karenina, and, I suppose, some of our celebrities who can’t seem to make their marriages work. Thus, the contrapasso is appropriate: the sinners now continue to experience something analogous to what they chose in life. They surrendered control of themselves to their passions, and now, as if to unveil and make clear to them what they once embraced, a strong wind drives them about and steals their freedom. They are like very small birds caught in a powerful windstorm.

It is at this time that Dante has a conversation with an extraordinary character, whom an influential Italian critic from the nineteenth century (Francesco de Sanctis) called “the first modern literary character.” Dante invites this soul and her companion to come to him, and the wind, seemingly according to providential design, momentarily calms to allow for a brief conversation. And then, like doves,

who, called on by desire,

with wings stretched out and held firm,

come to the sweet nest, carried on through the air by their choosing,

so too did these [Paolo and Francesca] leave the flock where Dido is,

coming to us through the malignant air,

so strong was my cry of affection. (Inf. 5.82–87)

As you can already see, the remainder of the canto will be expressed in an extremely high and delicate poetry. Woven in and out of these lines, in fact, are quotations from and paraphrases of the authors whom the young Dante had read and imitated during the days of his own love poetry. Dante the love poet is back! And then the woman, yet unnamed, comes forward to speak to the pilgrim:

“Love, who so quickly takes hold in the gentle heart,

took hold of this man through the beautiful appearance

that has been stolen from me; the way it happened afflicts me still.

“Love, who pardons no beloved from loving in return,

took hold of me so forcefully, through this one’s graceful charm,

that, as you see, it has not left me yet.

“Love brought us to a single death.” (Inf. 5.100–106)

Dante’s response is immediate:

“Oh, what loss!

How many thoughts of sweetness—and what desire!—

have brought them to this dolorous pass!”

Then I turned to them, and I spoke to them,

and I began: “Francesca, what you suffered

brings me to weep, with heartache and pity.” (Inf. 5.112–17)

It’s a subtle detail, but note that Dante did not need to be told the speaker’s name! Because he was a great master of the courtly love tradition, even just a couple of details sufficed for him to know exactly to whom he was speaking. This is Dante’s stuff, the stuff he read and thought about all the time as a young man. And note too the delicate rhetoric of Francesca’s speech: she uses a rhetorical device called “anaphora,” employing the key word “love” to introduce the three terzine of her speech: amor (100), amor (103), amor (106). Clearly, love was the ruling force of her life, the only reality to which she paid attention, just as amor is the fixed point that her rhetoric orbits now. Francesca then makes an argument suspiciously similar to that of one of Dante’s poetic heroes (Guido Guinizelli): if you truly have a noble heart, and someone falls in love with you, you cannot help but to return his or her love. Love seized me and wouldn’t let me go.

Dante wants to hear the sad end to such a seemingly noble beginning. How could such a great, pure-hearted lover end up here, in hell? Francesca concludes her story:

“We were reading, one day, for delight,

of how love once pressed Lancelot;

we were alone, suspecting nothing.

“On many occasions our eyes were drawn together,

thanks to the reading! And then it took the color from our faces;

and yet it was one point in particular that overcame us.

“When we read about how the long-desired smile

was kissed by that famous lover,

this one next to me—and he shall never be divided from me again—

“trembling all over, he kissed my mouth. . . .

That day we read no further.” (Inf. 5.127–36, 138)

This is the racy conclusion to her tale of adultery; we can imagine it easily being turned into a trailer for a steamy film. Dante, too, is absolutely smitten. He swoons on account of his compassion:

Ah, the pity!

I passed out as if I had died.

And I fell as a body falls in death. (Inf. 5.140–42)

In Italian, the final line is marked by thudding alliteration: “E caddi come corpo morto cade” (5.142).

When you know the background, Francesca’s sad story only becomes more moving. Her father, the ruler of Ravenna, was at war against the Malatesta family in Rimini, both cities on the Adriatic coast of northeastern Italy. Now it was common in the Middle Ages to marry off your teenage daughter, the equivalent of a high school sophomore, particularly when you could use that marriage to advance political relations. And so Francesca was married to Gianciotto Malatesta, who was, we may presume, older than she was. The situation is further complicated by the fact that Gianciotto was lame and deformed. Thus, Francesca found herself married to an older man whom she did not choose, whom she did not love, and to whom she was not attracted. And then along came the handsome younger brother, closer to her age and more to her liking—Paolo Malatesta. Francesca concludes her tale by famously describing her afternoon reading with Paolo. They were reading an old French courtly romance, which described, romantically, the adultery of Lancelot and Arthur’s wife, Guinevere. Right at the moment Lancelot and Guinevere kiss, Paolo and Francesca closed their book to imitate. One thing led to another. Eventually, they were caught together by Francesca’s husband, who murdered them both.

It is indeed a fascinating scene, and it raises a number of questions. Why would Dante portray the sin of Francesca so sympathetically? Is this the Tragedy of Francesca? Is her sad tale a story of how unavoidable circumstances in her life left her only one option, to follow her heart to find happiness? Again, Dante refuses to give us an easy answer. He wants us, here too, to be bothered by this passage, to be moved by the story. It’s another rock in the shoe.

We will have a chance to return to this scene many times throughout this book, but let me make two quick observations. First, Dante subtly points out that Paolo and Francesca did not finish the tale: “That day we read [the book] no further” (Inf. 5.138). They did not read to the end of the story, which is interesting, because if they had, they would have read about the humiliation that Lancelot and Guinevere brought on themselves through their adultery. They would have read about the friendships their liaison shattered. Second, this is another instance in which sinners in Dante’s hell get exactly what they think they want. There is no more pesky God or irritating church or outdated guilty conscience to try to deprive you of what you want. And so here Francesca and Paolo, at last, get one another with nothing intervening. They can remain together forever, clinging to that one thing that they chose, and continue to choose, to the exclusion of all else. When you think about it this way, the charm and romance of Francesca’s story begin to unravel. And although we might, at a certain level, admire the passion of Francesca’s love, in the end we have to admit that it is the only thing she does love. She has a rather idolatrous love. She loves one thing to the exclusion of everything else in the universe. It seems that Dante, in a fascinating way, has set the groundwork for a critique of Francesca’s love: it’s not that she loved too much and had too great a passion; she loved too little.

Mud, Rocks, and Swamps (Inferno 6–9)

In Inferno 6, Dante passes through the realm of the gluttonous (which for Dante would have included not just overeating but any kind of abusive use of food or drink, such as drunkenness and epicurean food snobbery). There the pilgrim meets a Florentine, Ciacco, who delivers the first powerful denunciation of Florence found in the poem. His speech is also the first to hint at Dante’s unhappy future, which will begin to unfold after the fictional date of the poem (1300). In this third circle, the pilgrim says that the punishment, even if it is not the most painful, is certainly the most disgusting. I know that all my readers have been caught before in one of those blinding rainstorms, from which, as soon as you could, you sought shelter. Well, here the souls in hell are continually buffeted by a kind of mixture of various forms of precipitation: cold rain, thick hail, and snow. The precipitation never lets up, so that the souls, lying on their sides, become tender and bruised. But it gets worse. The ground is mushy, and the rain mixture itself is dirty, tainted water, perhaps closer to vomit than to clean precipitation. The ground absorbs the mixture and reeks, like mud in the spring. This, of course, is Dante’s contrapasso for those who, in life, buffeted their bodies by eating and drinking too much. They drank and led the party life without moderation, seeking to achieve happiness by filling up their bodies with consumable materials.

Dante and his guide pass on into another circle, the fourth, where they encounter the avaricious and the prodigal, who are continually smashing into one another. As Virgil says, “Evil spending and evil grasping have taken / the lovely world from them and put them to this scuffle” (Inf. 7.58–59). Paradoxically, the poet placed into the same circle those who wasted through lavish spending and those who hoarded wealth out of fear of losing it—the person with all the credit card bills and the stingy man who builds himself a bomb shelter, just in case. On the surface, it would seem that these two sins would be the exact opposite and thus might merit different places of punishment, but Dante, along with the classical tradition extending back to Cicero and Seneca, sees a secret connection between them. Both groups, if I may, committed sins against rest. The ancients used to say that avarice makes a rich man poor—which is to say that the avaricious man, even as he receives something good, can’t fully enjoy it, because he’s thinking about the next thing he needs before he can rest from desire, just like the child who leaves the toy store, fists full of good things, talking about what she will buy when she returns. The avaricious man makes himself poor, becomes incapable of enjoying even the wealth he possesses. He cannot think about anything except the wealth he does not yet have or the wealth he could potentially lose. The prodigal man is never at rest because, like Paolo Sorrentino’s Jep Gambardella, he is addicted to the roller-coaster ride of pleasures, moving from one sensational experience to the next. At the same time, the miserly man can never rest in the good things he possesses, because he is constantly trying to save up more against some unforeseen disaster. Thus, both groups become blind to what wealth and beautiful things could potentially bring, because they are incapable of using well what they currently possess.

Dante neatly captures the burden of things by describing the punishment of the sinners: they are made to heave and lift huge boulders and push them forward, assuming at all moments that everyone else is out to take their large rocks. They were idolatrous in life, assuming that their earthly happiness would come from material things, and that narrowness of vision is here sadly embodied in their pathetically intense game of lifting worthless earth.

With this additional sad portrait in mind, Dante and Virgil travel to the next circle below, the fifth circle, where they find a small spring bubbling up with hot, dirty water. The water, though, flows down and collects to form a miry swamp. This is where the wrathful are punished. Again, Dante’s brilliant imagination creates this precise infernal landscape, which externalizes the interior condition of the wrathful—a small burning wound slowly leaks out anger, which pools in the recesses of the heart, dirties the mind, and incapacitates us to think about anything else.7 Ultimately, it breaks out in expressions of violent rage, a rage that does not heal us but just plunges us back into the foul-smelling mud.

After this quick tour of these three groups of sinners (one canto per sin), the pace slows down as Dante and Virgil are ferried toward the eerie city of Dis. They have ample time to survey the city as they approach it on a small skiff. The walls of Dis are made of iron, and tall towers can be seen within those walls; they resemble minarets extending high into the air, and they are all alight with flickering fire. It sounds very much like Hieronymous Bosch’s smoky, infernal landscape. More terrifying still for the pilgrim is his discovery that on top of the walls a host of evil guardians is watching over their city, like knights protecting their castle from a siege. Dante says there were “more than a thousand” infernal creatures: demons and unclean monsters of all types, drawn from ancient mythology. And they taunt the pilgrim as he approaches: “Let him—all by himself—return along his foolhardy path: / let him attempt it, if he knows how, for you, you will remain here” (Inf. 8.91–92). When the pilgrim hears this, his resolve is again shaken, just as in Inferno 2. He in essence says to Virgil, “If moving on to that which is beyond has been denied us, / let’s just retrace our footsteps together, and right away” (8.100–101).

But Virgil, the magnanimous poet who had written about heroes who are undaunted by such obstacles, steps forward, confident in his own ability to clear the path before him. He met success in doing so several times before this. Earlier, he shouted at Plutus, the guardian of the realm of the avaricious (Inf. 7.8–10). When the travelers encountered Cerberus the howling dog at the beginning of canto 6, Virgil gathered up some dirt in his hand and threw it into the dog’s mouth. At the beginning of canto 8, Phlegyas thought he had caught them (8.18), to which Virgil replied, “Phlegyas, Phlegyas, this time you shout into a void. . . . / You will hold us / only while we are crossing this bog” (8.19–21), and then he compelled the demonic guardian to ferry them to Dis. And so, here, outside of Dis, the Roman poet has grounds for confidence. He tells the pilgrim, “Be not afraid, since our journey / cannot be taken from us by anyone” (8.104–5). On this occasion, though, the old formula is not efficacious. Virgil’s authority and skill utterly fail. By the end of Inferno 8, the great Roman poet is both confused and embarrassed:

I could not hear what he put before them,

but he did not stand there long,

before each one rushed back within as if in a race.

They closed the doors, our wicked adversaries,

in my master’s face, and he stood there, outside.

He then returned to me with slow steps.

Eyes on the ground and brow

shorn of all confidence, he said in the midst of sighs:

“Who denies me the city of sorrow?”

To me he said: “And you, don’t be dismayed

because I criticize myself. No, I will conquer in this battle,

whatever it is they are putting together in there for defense.

“This insolence of theirs is not new;

they displayed it once before at a less interior gate,

the one that can still be found without lock or bolt.” (Inf. 8.112–26)

In the final lines of the passage above, Virgil makes reference to the portal of hell, whose inscription we discussed earlier in this chapter. As I mentioned, a lot of medieval artistic images show the gates of hell kicked in by Christ, when, after his death but before his resurrection, he came down to hell as a conqueror and liberated all the souls of the patriarchs. In light of Christ’s success against the demons who barred the doors against him, Virgil’s failure, and his speech afterward, is revealing. He asks, speaking more to himself than to Dante, “Who denies me,” soon continuing, “I will conquer.” At the beginning of canto 9, we hear him arguing quietly with himself: “Yet we must overcome in this fight . . . / or else. . . . It was promised to us. / How long it seems to me till someone joins us!” (Inf. 9.7–9). Virgil is not very good at waiting.

It’s a fascinating scene, which scholars have compared to a medieval siege (a common thing to describe in medieval literature), but here it’s a laughable parody! A proper medieval siege would have been conducted by a vast army, with many soldiers and engines of war. Instead, we have just two dudes, two unarmed travelers standing outside a huge, bolted gate, which is defended by thousands of guardians. And it seems that some of these monsters are such a threat that even one look alone could undo the pilgrim.

Thus, we have a series of images that stack up and issue all kinds of question marks: Why does the divinely appointed journey halt here? Why does Virgil, the poet of magnanimity and eloquence, fail? It is at this moment that the poet appeals to his readers:

O you who have upright understanding,

look for the teaching that is hidden

under the veil of these strange verses. (Inf. 9.61–63)

Dante asks his readers to lift the veil, which hides some mystery underneath. And right after this famous address to his readers comes one of the most sublime moments in the Comedy.8 While the pilgrim is waiting for what he hardly knows, worried that his guide has led him, unsuspecting, into a dead end in a remote and dangerous corner of hell, an unexpected rushing wind begins:

And now there was coming up upon the turbid waves,

a crash of sound, full of fright,

on account of which both banks were trembling.

Just like that sound we hear when the impetuous wind,

moving through the contrary pockets of heat,

savagely attacks the forest and, without relenting,

smashes against the branches, beats them, and carries them away;

and then the dusty blast moves onward, proud,

and forces beasts and shepherds alike to flee. (Inf. 9.64–72)

What appears is an angel of God, who arrives and drives the evil spirits away as if they were just annoying frogs. The evil spirits disappear instantly, terrified. Indeed, Dante’s angel is not the saccharine image from those terrible pastel paintings but rather a force of power that would make you tremble. He is disdainful, full of a righteous anger, and irritated that he has to be absent from heaven even for this short time. Again, an earthquake of sorts irrupts in the midst of hell. God invades again (as he had done during the harrowing of hell) and casts aside the evil opponents who oppose him, as if they were leaves in a strong wind.