10

As the Heavens Are Higher Than the Earth: Dante’s Apocalyptic Vision

(Purgatorio 29–33)

The End of the Story?

By the end of Purgatorio 27, it seems that our story is coming to its close. Virgil has accomplished his task. He saved the pilgrim from the dark wood and restored his ability to choose the good. He leads the pilgrim to believe that all that remains is for him to enjoy this fresh and verdant place and await the time at which he may look into the beautiful eyes of his beloved Beatrice (Purg. 27.136–37). At any moment, then, the reunion between lover and beloved will take place. Zygmunt Baranski summarizes it in this way:

After several dramatic days of testing travel through Hell and Purgatory, which have taxed him intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually, Dante-character, reassured by an enchanting dream, wakes—for the first time on his journey—in a peaceful and relaxed manner. . . . He soon finds himself on the edges of a locus amoenus [perfect garden]. . . . The pilgrim is nearly home. . . . The viator [pilgrim] seems, at last, to have reached a deserved haven of calm and repose; he is about to be rewarded for his efforts. . . . [But the canti that follow] most certainly do not depict a moment of calm and harmony; nor do they describe a charming reunion between long-separated lovers. . . . Beatrice is angry, unrelentingly reproachful, and vigorously incisive. . . . The pilgrim, in his turn, is ashamed, confused, and almost at a loss for words.1

As we will see, something is about to spin terribly out of control.

As it turns out, this is not the end the pilgrim thought he was in for. Rather, Dante the pilgrim witnesses not the serene advent of the lady he had once loved so much, a kind of romantic reunion in this ideal garden, but a supernatural apocalyptic procession. Just as he begins to look about the woods expectantly for Beatrice, the pilgrim sees this instead:

And behold: a burst of light all of sudden passed through

every part of the great forest,

such that it struck me: this is lightning, perhaps.

But since lightning, as soon as it comes, then settles down,

and this brilliance, shining on, became more and more resplendent,

I said to myself in my thoughts: “What thing is this?” (Purg. 29.16–21)

The pilgrim has difficulty even identifying the nature of the eerie event. The images he uses to describe it become more unnatural as the canto proceeds. A sweet melody courses through the luminous air, as if the sound and the color were the same (29.34–36). The company flames more brightly than the moon at midnight (29.52–53), and as they advance, the air is transformed into a colored substance (29.73–74), as if they are so steeped in heavenly light that they burn color into the air as they pass through it. The poet turns to a synesthetic blending of images to gesture at what he saw, as if wildly gesticulating at something well beyond language (he sees sounds and hears sights). The world of nature begins to melt down in the heat of this extraordinary event.

In the previous chapter, I talked about the beautiful, moving poetry that Dante used to craft a description of the pilgrim’s experience of the earthly paradise in canto 28. In contrast to that tranquil melodic flow, we have now a violent, experimental poetry in canto 29. In earlier canti, you can find poetic traces of the “sweet new style”: echoes of the poems of Cavalcanti and Guinizelli. But now, that mellifluous lyricism is replaced by bizarre imagery, opaque symbolism, strangely symbolic pageants, and intentionally dark and difficult “explanations” that make things less intelligible rather than clearer. In a word, love poetry has yielded to that frightening landscape of the biblical apocalypse.

Dante, the Numinous, and the Apocalypse

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the German Lutheran theologian Rudolf Otto wrote the now-famous Idea of the Holy. In this book, which influenced, among others, C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien, Otto pointed out that modern people have rather lost a sense of what the holy is. We tend to think of “holiness” as good brought to the highest level. In reality, Otto claims, all ancient religions treat the holy as an “irrational over-plus of meaning” that extends beyond goodness, what he termed the “numinous”: “There is no religion in which [the numinous] does not live as the real innermost core, and without it no religion would be worthy of the name.”2 For Otto the numinous is that reality whose majesty is so far beyond our ordinary experience that it is difficult for us to classify it simply as good or bad; it is at once both alluring and dangerous, beautiful and terrifying. The numinous is what Tolkien had in mind when he describes Lothlorien, the land of the elves in The Lord of the Rings, and what Lewis had in mind when he describes those moments in which Aslan appears in The Chronicles of Narnia in the fullness of his power. Visionaries describe an encounter with the sacred as a sense that it is rushing forth while at the same time drawing them in. For this reason, it inspires a dread in the creature who comes into contact with it. It inspires a feeling of terror and vulnerable creaturehood.

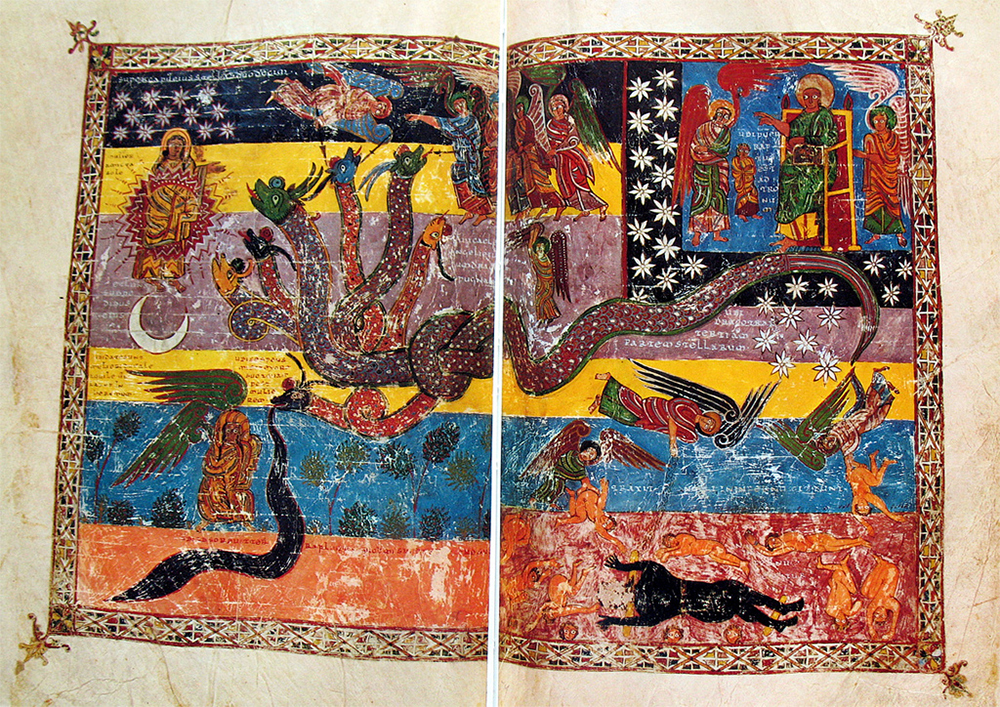

In any case, it is this perception of the awful majesty of God that Otto thought the modern world needed to recover. In contrast, this sense of the awful, sacred presence of God was palpable in the medieval world, particularly within the visionaries and commentators who took as their inspiration John’s Apocalypse, the book that uses famously difficult and symbolic language about the lady, beast, righteous martyrs, seals, and bowls of judgment. In addition to providing the secret history of the world, medieval readers believed that the Apocalypse, in all its strange and enigmatic language, briefly pulled back the veil of reality and let us see the awful truth of the majesty of God enthroned.

Figure 5. Imagery from John’s Apocalypse in the Morgan Beatus, a tenth-century illuminated manuscript. [Manuscript_nerd CC BY 2.0 / Wikimedia Commons]

This is also what our poet was aiming for in these canti: to conclude Purgatorio in a way as phantasmagorical and brilliant as any vision or illuminated manuscript inspired by the Apocalypse. It shouldn’t surprise us, then, that what Dante sees, and indeed feels, in these last canti is steeped in the imagery of the books of Revelation and Isaiah and Ezekiel. He sees a bizarre procession that comes from heaven and dreamily alights within the garden in order to present Dante with a silent play. He is ordered, like John, to write down what he sees, although he barely understands what it means (Purg. 32.103–5). Thus, he dutifully records that the long parade is led first by twenty-four elders carrying lilies, four beasts with brightly colored wings, and a chariot pulled by the griffin carrying Beatrice. On one side of the chariot is a group of three female figures, dressed in red, green, and white (they represent faith, hope, and charity); on the other side a group of four ladies are dancing in purple (the cardinal virtues); then come two old men, a doctor and one carrying a sword. The old men are followed by four humbly dressed men, who are in turn followed by a sleepwalker. Canto 30 tells us that one hundred angels will join the procession, for a total of precisely one hundred forty-four members in this sacred parade.3

Dante doesn’t tell us explicitly, but the twenty-four elders seem to be the twenty-four books of the medieval Old Testament; the four living creatures symbolize the four Gospels; the two old men, Luke and Paul, are followed by four humbly dressed individuals—Jude, John, Peter, and James—who are in turn followed by the sleepwalker, the author of the Apocalypse. So the Bible and the virtues, as it were, are processing into Dante’s world to meet him.

Note how painstakingly the poet points out the color of everything throughout these verses, as if he wants us to read this scene and feel it as a painted illumination. The procession strikes like a bolt of lightning that doesn’t flicker out; it paints the air it passes through; ladies wear bright dresses; the griffin has golden wings; Beatrice wears an olive crown, white veil, red robe, and green mantle. But the pilgrim barely registers any of this. He’s too stunned by the glory of the event. At two points he turns to Virgil for help in understanding:

I turned, full of wonder and marvel,

to my good Virgil, but he answered

with a look no less full of stupor. (Purg. 29.55–57)

Garrulous and avuncular Virgil, always full of calm and beneficial advice, just shakes his head; he too is completely at a loss to explain this event.

Then it gets worse. When Beatrice does arrive, she is brutally personal, even sarcastic. When the disoriented pilgrim turns for the last time to Virgil, to discover that his faithful guide and friend is not there, Beatrice says, “Do not weep yet, do not weep yet— / it is better that you weep by another sword” (Purg. 30.56–57). She later asks him, “How did you dare come to the mountain? / Maybe you didn’t know that here man is happy?” (30.74–75). Beatrice shames Dante in front of a huge crowd, which makes the experience all the more painful. In fact, she’s so harsh that the pilgrim passes out, overwhelmed by the surprise of this verbally abusive encounter. How great a contrast to what was expected! What is the point of these final canti, this shocking reunion?

At exactly the same time, Dante portrays his encounter with Beatrice as intimately personal as well as representative of all humanity. When the pilgrim first comes into the presence of Beatrice, he experiences again that trembling that he felt as a young man, described so vividly in Vita Nuova (Purg. 30.34–39). Dante is, once again, the overwhelmed lover, shaken by the glory of Beatrice’s beauty. In fact, Beatrice can unabashedly say to Dante, “Never, never did art or nature present to you / delight like my beautiful members did / in which I was enclosed” (31.49–51). For this reason, Beatrice can accuse Dante of being unfaithful—that is, unfaithful to her beauty:

“And if the highest delight failed you

upon my death, how is it that a mortal thing

could draw you after it in desire?

“You ought to have, at the very first wound

inflicted by deceitful things, risen upward

after me who was no longer merely mortal.” (Purg. 31.52–57)

In other words, how is it possible that you could have settled for anything less? Surely, any other attractive thing ought to have struck you as a pale shadow after you had a real experience of beauty. Beatrice exposes, as it were, the pilgrim’s primal act of infidelity: sinning against the memory of her. Dante falsified his own experience, feigning to himself that any beauty could remotely compare.

It is at this point that Beatrice forcefully elicits a confession from the confused pilgrim; she demands that he admit that he had been unfaithful to her, unfaithful to love, unfaithful to beauty. In the midst of this overwhelming experience, the pilgrim can barely whisper an answer:

After drawing forth a bitter sigh,

I found my voice to reply, but only with great pain,

and my lips gave shape to my voice, but with labor.

In tears, I said: “Things put in front of me,

with their false delight, turned around my steps,

the moment that your face was hidden from me.” (Purg. 31.31–36)

In a moment of complete vulnerability and spiritual nudity, Dante has to let his soul be radically known, to let all of its secrets be viewed by all. From this vantage point, all the “false images of good” don’t just seem misdirected; they seem paltry, pathetic, reprehensible, detestable, sick, and small. By confessing his primal act of infidelity against Beatrice, the pilgrim is forced to return to the “root” of his soul, an idea that Dante hints at in one of the most powerful passages of this scene:

With less resistance you can rip out, by the roots,

a massive oak . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

than I lifted my chin at her command.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Then the nettle of repentance so stung me

that whatsoever had once drawn me,

the more I loved it, the more it now became hateful. (Purg. 31.70–71, 73, 85–87)

And yet, while Dante endures this excruciatingly personal confession, being made to uproot sin from the core of his being, he also has returned to the root of humankind in the garden. Having returned to the garden on behalf of humanity (and reentered the state of original justice), Dante has become a kind of new Adam, and thus he must also confess and unchoose, as it were, humanity’s original act of infidelity, the act in which humans presumed that all things lay within their reach. Human perfection is a beautiful thing, but even such perfection has to be understood as a limited power within the larger context of God and the cosmos.

Thus, throughout these canti, the poor pilgrim, laboring to keep up, can barely understand what’s happening around him. And when he asks for explanations, Beatrice’s words only make things more difficult to understand. For example, Beatrice’s explanation of the mysterious pageant just adds to the riddle: “Know that the vessel which the serpent broke / was and is not,” she says (Purg. 33.34–35). She refuses to explain what the eagle stands for. Nor does she explain the fox, the harlot, or the giant, but rather says that those figures have to be understood as referring to “the 500, 10, and 5.” Here her speech becomes “dark narration” (33.46), a “hard enigma” (33.50). And so the pilgrim quite understandably asks:

“But why do your words, so long desired,

soar so high above my sight,

so that the more they help me, the more I am lost?”

Beatrice responds:

“So that you know,” she said, “that school

you followed, and see how well its doctrine

can follow my words;

“and so that you may see that your way is as distant from

the divine as the highest heaven, which moves so swiftly,

is out of tune with the earth.” (Purg. 33.82–90)

Dante never mentions what specific “school of thought” it is that Beatrice criticizes, but scholars have suggested that Beatrice here rebukes, not so much particular false doctrines, but rather a presumptuous mind-set that could believe that any set of human, rational explanations could effectively communicate all that needs to be known. Indeed, Beatrice suggests that the very darkness of her words was intentionally planned in order that the pilgrim recognize by how much heavenly realities exceed earthly ones, that he recognize how poorly equipped he is to understand opaque celestial truths with earthly rational instruments. The poet then creates a dreamlike sequence of canti, full of obscurity and mystery, in order to help the pilgrim, standing in for humanity, “unchoose” man’s original act of presumption. Dante has returned to the garden, as a second Adam, to undo the original father’s mistake.

In a way, then, this is Dante’s ultimate justification for using poetry. Here in the garden, the dreamlike, apocalyptic images, which resist rational categorization, invade, as it were, the supreme seat of human reason. We have a de facto announcement that the poetry that is to follow will be something that has never been seen before, because it will attempt to treat what is beyond nature. From here on out, the Virgilian tradition will be able to offer little assistance, just as the Roman poet is of no help here in the garden. From here on out, the poet will have to strike out on his own; he will have to be radically innovative as he treats something never attempted before—and this is exactly what he says at the beginning of the next canticle: “The waters that I enter have never before been crossed” (Par. 2.7).