My mother, Barbara Holmes, joined the Women’s Land Army in 1943, aged 19.

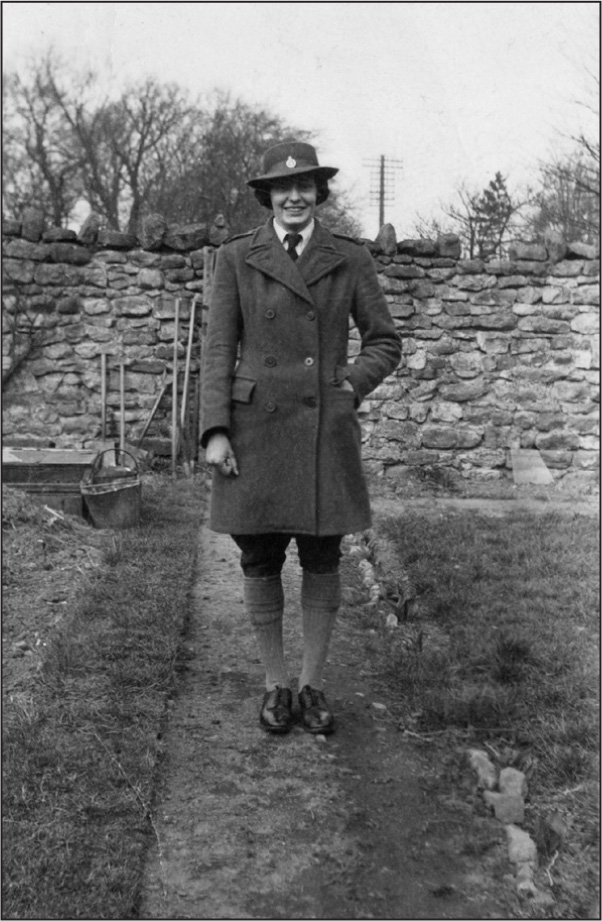

I have two black-and-white photographs of her in uniform that were taken in the back garden of her family home in Beckwithshaw village just outside Harrogate, North Yorkshire. In one she stands bareheaded in shirt and tie, knitted sweater, corduroy breeches, long socks and brogues. The other shows her in a short, belted coat and felt hat, complete with Land Army badge. They capture her in characteristic stance – her head tilting shyly forward, but smiling proudly.

Like Grace in the novel, she continued to live at home to help her father run the village pub, with her two older sisters Connie and Sybil, and twins Joan and Myra. Brother Walter was in the RAF and Ernest had joined the army.

Practical by nature and upbringing, she took to Land Army tasks with determination and gusto, working alongside old school friends for neighbouring farmers whom she’d known all her life; namely, the landowning Williams family who held an almost feudal status in the village (they owned the Smith’s Arms and most of the houses, built the church, vicarage and village institute) and the Wintersgills’ hen farm that was close to the now famous RHS Harlow Carr.

There was a certain glamour attached to being a Land Girl – at least to the image of it if not the reality, which meant ploughing, tractor driving, digging, weeding, trimming and labouring in all weathers. After working all day in the fields, Mum would cycle home to join her sisters behind the bar in the Smith’s Arms. It was here that she met my father, Jim Lyne, home on leave from the Royal Navy in 1944. The story goes that Connie looked out to see him and his pals crossing the yard. ‘Watch out, here comes the Navy!’ she warned. Well, the Navy arrived in Mum’s life and never left. There was a whirlwind courtship and an engagement soon after; a ruby and emerald ring and long separations while Dad served in the Mediterranean, only returning home on leave on rare occasions.

Meanwhile, disaster! Mum’s precious ring was lost while working in the hen huts. She and her Land Girl pals were down on their knees in a frantic search through beds of straw. Triumph; the ring was found and safely restored to Mum’s finger in time for Dad’s next shore leave.

Like many women of the time, once the war ended, Mum settled into the more traditional roles of housewife and mother. She rarely looked back to her wartime service, except perhaps to mention that the uniform was hard wearing and well made, especially the coat, or that the life was hard but worthwhile. She never boasted about her contribution to the war effort or softened her experience with fond nostalgia. That was not her style.

But I found among her possessions after her death in 2008 a plain, somewhat scuffed cardboard box. I opened this little treasure carefully and folded back the tissue paper to reveal a small green and red enamelled badge, embellished with a wheat sheaf and a royal crown with three words that sang out Mum’s unspoken pride. The badge read ‘Women’s Land Army’.