Apart from wishing to effect a personal reconciliation with the Governor-General, and to obtain recognition of his services in Java, Raffles’s principal purpose in visiting Calcutta was to seek approval of the measures he had taken in Sumatra and to alert Hastings to the dangers of a resurgence of Dutch power and influence in the Indonesian islands.

Before he left England for Bengkulu late in 1817, Raffles had proposed in a paper submitted to George Canning, President of the Board of Commissioners for the Affairs of India,33 various measures to protect British commercial interests in the Eastern Archipelago. Chief among these measures was the establishment of a British port which would serve as a resort for the independent trade and “for the protection of our commerce and all our interests, and more especially for an entrepôt for our merchandise”. He thought that the East India Company’s existing stations at Bengkulu and Pinang were too remote to serve these purposes, and he considered that a settlement should be formed on Pulau Bintan in the Riau Archipelago, which would become “a commercial station for communication with the China ships passing either through the Straits of Sunda or Malacca, [and so] completely outflank Malacca, and intercept its trade in the same manner as Malacca has already intercepted that of Prince of Wales Island”. It would possess great advantages as vessels from China, Cambodia, Thailand, Patani and Terengganu “must pass in sight of that island, which forms the southern side of the Strait of Sincapore at its opening from the China seas”. If, however, this proved impossible, a British station might be established in the vicinity of Sambas or Pontianak in western Borneo.34

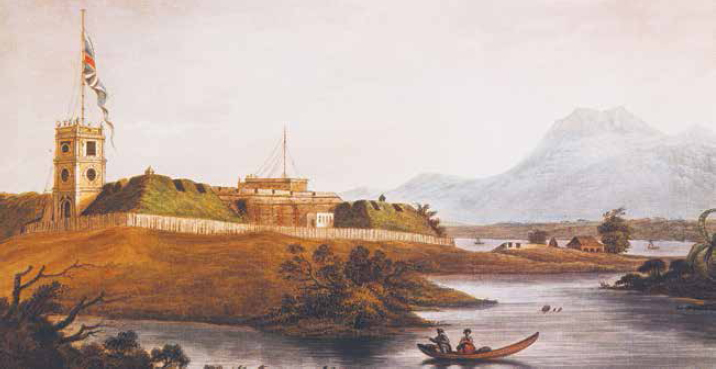

Fig. 11

Fort Marlborough, Bengkulu, built by the British East India Company 1713–19.

Aquatint by Joseph Stadler after a drawing by Andrews, 1799.

Raffles had disclaimed all intention of seeking an “extension of territory”,35 but after taking up his post as Lieutenant-Governor of Fort Marlborough in March 1818 his ideas quickly changed, at least with respect to Sumatra, because of what he regarded as the aggressive measures adopted by the newly installed Dutch Commissioners-General at Batavia. “Prepared as I was for the jealousy and assumption of the Dutch Commissioners in the East”, he wrote to the Secret Committee a month after his arrival,

I have found myself surprised by the unreserved avowal they have made of their principles, their steady determination to lower the British character in the eyes of the natives, and the measures they have already adopted towards the annihilation of our commerce, and of our intercourse with the Native Traders throughout the Malayan Archipelago. Not satisfied with shutting the Eastern ports against our shipping, … they have dispatched commissioners to every spot in the Archipelago where it is probable we might attempt to form settlements, or where the independence of the Native Chiefs offered any thing like a free port to our shipping.

These included the Lampungs in southern Sumatra, as well as Pontianak and the minor ports of Borneo, and even Bali. Moreover, a Dutch Commissioner from Batavia had recently been despatched to Palembang, “to organize, as it is said, all that part of Sumatra”. Because of these activities, Britain had been left without “an inch of ground to stand upon between the Cape of Good Hope and China”.36

Raffles wrote in even more dramatic terms to his friend, Charlotte Seymour, Duchess of Somerset, on 15 April 1818:

The Dutch are worse than I even expected, and your Grace knows that was bad enough – they are doing all they can to exclude us from the Eastern Seas altogether and have already obliged most of the Independent Ports to submit to their authority … My arrival has I understand created the utmost alarm – I believe they look upon me as worse than Buonaparte – they say I am a spirit that will never allow the East to be quiet and that this second Elba in which I am placed is not half secure enough – The Dutch keep up a force of 3 line of Battle Ships[,] half a dozen frigates & innumerable smaller vessels to enforce their regulations, but thank god they dare not interfere with me personally – I have written home very fully on the subject and if the Government is not right down mad, Ministers & the East India Company must interfere – it will not be long I think before we come to close quarters – I am now endeavoring to establish a position in the Straits of Sunda, [and] if I succeed in this, I shall soon set up a Rival Port to Batavia & make them come down to my own terms –.37

This is a reference to what he described to the Secret Committee on 3 July 1818 as “a respectable Establishment” in Semangka Bay, which would secure the passage of the Sunda Straits for the East India Company’s outward and homeward bound ships and would be retained pending a reference to Europe.38

Fig. 12

Charlotte Seymour, Duchess of Somerset (1772–1827), with whom Raffles maintained a steady correspondence from 1817 until his death.

Contemporary miniature portrait.

Furthermore, in order to induce the Dutch to withdraw from Palembang, Raffles informed the Netherlands authorities at Batavia that Padang and Melaka would not be returned to them as provided by the Convention of 1814. “The position I have taken up”, he wrote, “is that the Dutch can have no claim to possession where their flag did not fly on the 1st January 1803; and under this view, [their] claim to Malacca and Padang is at least questionable, these stations having been under the English flag since 1795”. If the British were obliged to hand over Melaka, there was always the possibility of forming an establishment in the Riau Archipelago, or on some adjacent island. Moreover, if the Dutch formed a connection with Pontianak, a rival post could be established at Sambas. This might lead to regional conflicts, so it would be better if the Dutch were compelled to withdraw from Borneo altogether, or at least recognise the Equator as the boundary of their settlements. Java was in their exclusive possession, but their pretensions to Sumatra should be discounted and the integrity of the island maintained. “Sumatra”, wrote Raffles, “should undoubtedly be under the influence of one European Power alone, and this power is of course the English”.39

After establishing the small British station at Kalambajang east of Semangka Bay, Raffles wrote to the orientalist, William Marsden:

I am already at issue with the Dutch Government about their boundaries in the Lampoon country … I demand an anchorage in Simangka Bay, and lay claim to Simangka itself. If we obtain this, we shall have a convenient place for our China ships to water; and should we go no further within the Archipelago, be able to set up our shop next door to the Dutch. It would not, I think, be many years before my station in the Straits of Sunda would rival Batavia as a commercial entrepôt.40

Following the arrival of a Dutch Commissioner at Palembang, and the consequent appeal in June 1818 by Sultan Ahmad Najmuddin for assistance,41 Raffles despatched a small force of 100 men overland under the authority of Captain Francis Salmond, the Master Attendant at Bengkulu, with instructions to afford the Indonesian ruler “the protection of the British Government”.42 Salmond was placed under arrest by the Dutch Commissioner, H.W. Muntinghe, and sent as a prisoner to Batavia, eliciting from Raffles a formal “Protest” to the Governor-General G.A.G.P. van der Capellen about the treatment of a “publicly accredited and recognised” British representative, and also about the system pursued by the Dutch authorities which appeared to aim “at an absolute despotism over the whole Archipelago”.43 The object of the “Protest”, he explained in a letter to Charlotte, Duchess of Somerset, on 13 August 1818, was “to bring the different questions at issue to a point – and to oblige our Ministers to come to some immediate understanding with the Dutch Authorities in Holland”.44 The “Protest”, which was published in the Annual Register for 1819,45 and given wide coverage in the English and Scottish press,46 caused “a great sensation”, with consequent embarrassment and annoyance to the British Government and the East India Company.

Fig. 13

Baron G.A.G.P. van der Capellen (1778–1848), Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies 1816–26.

Portrait by C. Kruseman.

Raffles sent a copy of the “Protest”, together with his correspondence with the Dutch authorities at Batavia, to the Secret Committee on 12 August 1818, under a covering letter in which he argued for the maintenance of “the integrity” of the larger islands of the Malay Archipelago: “Could the return of Banca be negociated and the integrity of Sumatra be preserved under British Protection, the greatest advantages might be anticipated”.47

The Secret Committee replied in a despatch to the Governor-General dated 30 October 1818:

Having attentively examined the agreement concluded with the present Sultan of Palembang upon his elevation to the throne, we find no article by force whereof we are under any obligation of interference, or have any right to interfere in the manner described by the Lieutenant Governor of Bencoolen. If the Dutch, or any other European power, shall wantonly oppress that weak state, still more if their oppressions shall be auxiliary to hostile projects against the British government, there may exist a case for extraordinary interference … But it would be a strong measure to object to the establishment of a Dutch Residency or Factory in the Palembang country, merely because the ancient practices of that Nation gave us reason to apprehend that their ulterior designs may be mischievous or inconvenient to us.48

Raffles met with more success in extending British informal control over the region of Pasemah ulu Manna in southern Sumatra, which he visited in May 1818 ostensibly for the purpose of preventing incursions by the Pasemah people into the British Out-Residency of Manna. Before his visit, local British officials had attempted to reduce friction between the Pasemahers and the coastal peoples by regulating trade and issuing passes to those wishing to enter the East India Company’s districts; but when the contract system of supplying pepper was introduced at the beginning of the nineteenth century,49 British supervision of the remoter districts was withdrawn, leaving the people in Manna largely unprotected against attacks by their neighbours.50 The British Resident had concluded a treaty with Pasemah ulu Manna in 1815,51 but according to Raffles this had been broken by British officials themselves.52 When he visited the region in 1818, he found the people “reasonable and industrious, an agricultural race more sinned against than sinning”,53 and after consulting with the rulers he agreed to pay compensation and allow the cultivators the option of planting pepper on the same terms as those of the coast. They were also permitted to settle where they wished and the pass and the toll systems were abolished. In return, the rulers of Pasemah ulu Manna agreed by treaty to accept the East India Company’s protection of their country.54 This arrangement seems to have produced general peace and stability in the region during the remaining period of British rule, and even found favour with the Supreme Government in Bengal, which considered it to have been “well calculated to promote the welfare and happiness of the inhabitants of that part of the country”, an opinion shared by the Directors of the East India Company.55

On returning to Bengkulu in June 1818, Raffles found a Dutch officer waiting to take charge of the settlement of Padang, which had been in British hands since 1795.56 As the Anglo-Dutch Convention of 1814 had referred to the cession of only those colonies which had been in the possession of the Netherlands at the Peace of Amiens, Raffles refused to return Padang until the costs incurred by the British administration were settled.57 He decided, moreover, to visit Padang himself, accompanied by Lady Raffles and the American naturalist, Dr. Thomas Horsfield,58 and when the party travelled inland to Pagarruyung in the central highlands,59 he concluded treaties with the Minangkabau rulers providing for the cession of Padang and the coastal regions from Inderapura to Natal to Great Britain, and for his own appointment as British “Representative in all the Malay States”.60 In this role Raffles imagined reviving the ancient authority of Minangkabau and creating a strong central government in the island under British control.61 He accordingly stationed a British agent with a small Bugis force in central Sumatra and determined to oppose any Dutch attempt to return to Padang. “[W]ith an influence at Menangkabau and the exclusion of the Dutch from Sumatra,” he wrote to the Secret Committee on 5 August 1818,

Fig. 14

Lady Raffles, born Sophia Hull (1786–1858), married Stamford Raffles in 1817.

Miniature portrait by A.E. Chalon, 1817.

a prospect is now held out of rendering Sumatra within a short period as valuable a possession to Great Britain as Java. It is certainly in a less cultivated state, the People less civilized, and much remains to be done, but I am satisfied that by a liberal and enlarged policy, a very few years would be necessary to draw forth most important revenues … At all events, as the British Government has now obtained the sovereignty of the country, I consider it impossible that the Dutch can be permitted to do more than re-establish a Commercial Factory there –.62