Plate 1. Statesmen of the Great War: Sir James Guthrie’s theatrical depiction (1924–30), with Arthur Balfour, wartime foreign secretary, standing (center). Seated to the right of Balfour is Herbert Asquith, prime minister until 1916; to the left, leaning forward, is Sir Edward Grey, foreign secretary in 1914, then Winston Churchill and, two farther down, David Lloyd George, Asquith’s successor as premier.

Plate 2. Tomáš Masaryk, father of the new Czechoslovakia, on a postcard celebrating Czech-American solidarity with President Woodrow Wilson, whose calls for national self-determination ignited anti-imperialist feeling across the world.

Plate 3. On a 1915 recruiting poster John Redmond, leader of moderate Irish nationalism, calls for patriotic Irishmen to fight with the British Army to defeat German militarism and thereby win Irish Home Rule.

Plates 4 and 5. Two views of a very different Irish nationalist. Éamon de Valera in Dublin in 1916, under British military arrest after the Easter Rising, and as president of Ireland in 1966, escorted by his own soldiers during commemorations for the fiftieth anniversary of the Rising.

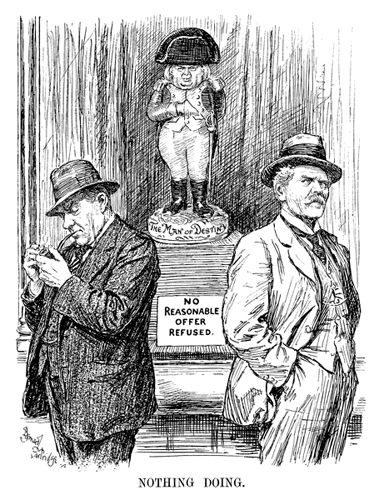

Plate 6. The two “ordinary men” who dominated interwar British politics, Stanley Baldwin (left) and Ramsay MacDonald, turn their backs on the Napoleonic figure of Lloyd George. A Bernard Partridge cartoon for Punch, June 12, 1929.

Plate 7. The other “superman” of the era depicted as “Adolf Churchill” by Will Dyson in the Daily Herald, March 30, 1933, two months after Hitler seized power in Germany. Dyson was satirizing Churchill’s die-hard campaign to maintain British rule in India.

Plates 8 and 9. In the early 1930s a consumer boom and the availability of cheap mortgages via Building Societies helped pull southern Britain out of the slump and head off the appeal of extremist politics that wracked the continent.

Plate 10. British avant-garde war art remained representational. Richard Nevinson’s painting of a French machine-gun crew locked into their gun, La Mitrailleuse (1915), was Futurist in style but appealed to critics, civilians, and soldiers alike.

Plate 11. Paul Nash used Cubist techniques to evoke the blasted landscape of The Menin Road (1919) outside Ypres, where thousands of British Empire soldiers met their end—a landscape (and a war) from which there seems to be no exits.

Plate 12. John Singer Sargent was a grand old man of British society portraiture. But Gassed (1919) captured the pity of war and the dignity of its victims with unique power.

Plate 13. The Peace Ballot of 1935 was signed by 11.6 million people, over a third of the UK’s population. The results showed strong support for the League of Nations, but opinion was split down the middle on the use of force to keep international peace.

Plate 14. In October 1939, a few weeks into another great war, the next generation of soldiers set off for Cambridge railway station, paying wary respect to the men who marched away in 1914—never to return. Cambridge Daily News, October 21, 1939.

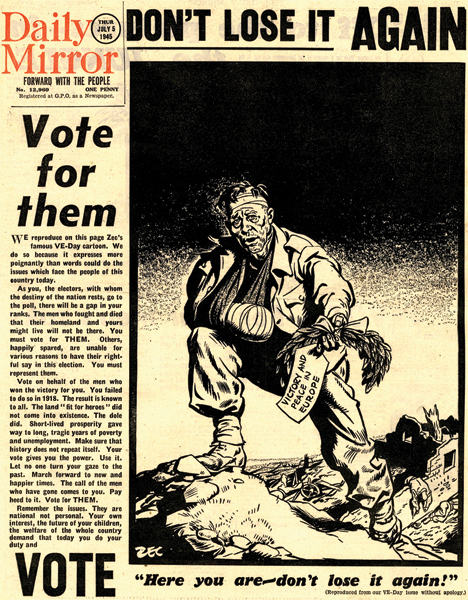

Plate 15. Zec’s cartoon for Victory Day on May 8, 1945, was reprinted by the pro-Labour Daily Mirror for the General Election on July 5, 1945. This warning—that the people had won the war of 1914–18 but lost the peace—was fundamental to Labour’s manifesto and its postwar program.

Plate 16. By the mid-1930s most Americans regarded their entry into the Great War as a disaster. Here banker J. P. Morgan (right) confronts Senator Gerald P. Nye of North Dakota during Nye’s inquiry into how the “merchants of death” in Wall Street and the arms industry had supposedly dragged America into Britain’s war.

Plate 17. But after Pearl Harbor, Woodrow Wilson’s war was gradually rehabilitated. The 1944 movie Wilson depicted the president (played by Alexander Knox) as an internationalist visionary, tragically frustrated by parochial pigmies on Capitol Hill.

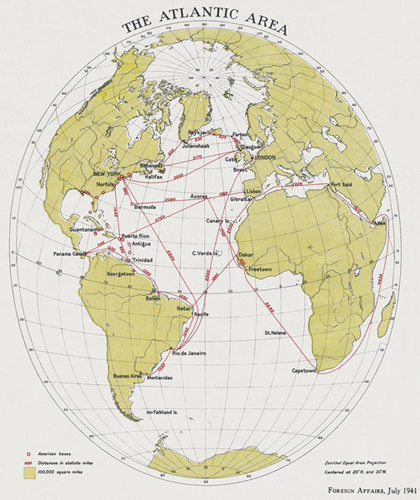

Plate 18. In this map from the journal Foreign Affairs, July 1941, the Atlantic—for isolationists an oceanic barrier against aggressors—becomes a lake linking the countries of western civilization. This points towards the “North Atlantic Treaty” of 1949.

Plates 19 and 20. Opening captions from the BBC TV series The Great War (1964), which helped reshape British attitudes fifty years on. The descent into the hell of the trenches (top) and (bottom) the haunted face of a solitary survivor.

Plates 21 and 22. In fact the lone soldier had been cropped from a group photo of Royal Irish Riflemen on the Somme in 1916, but the image has become perhaps the most familiar face of a Great War Tommy—used here for the cover of a book to accompany the Imperial War Museum’s 2002 exhibition about 1914–18 war poets.

Plate 23. Edmund Blunden, one of the soldier poets who survived 1918, helped shape our sense of “true” Great War poetry through his introductions to anthologies and his editing of Wilfred Owen’s poems.

Plate 24. The Central London Recruiting Depot, August 1914. Men queuing for war, it seemed to Philip Larkin, like crowds to watch a cricket match. This picture inspired his poem “MCXMIV” (published 1964), which evoked an idyllic prewar world.

Plates 25, 26, and 27. By the late 1990s Northern Ireland was finally moving out of the Troubles. The Island of Ireland Peace Tower (top) near Mesen/Messines in Belgium, commemorated the men of the whole of Ireland who fought in the British Army in 1914–18. It was dedicated by Mary McAleese, the Irish president, and Queen Elizabeth II on November 11, 1998 (middle). Three tablets (bottom) record the dead from the Ulster division and two Irish divisions who fought alongside one another in 1917.

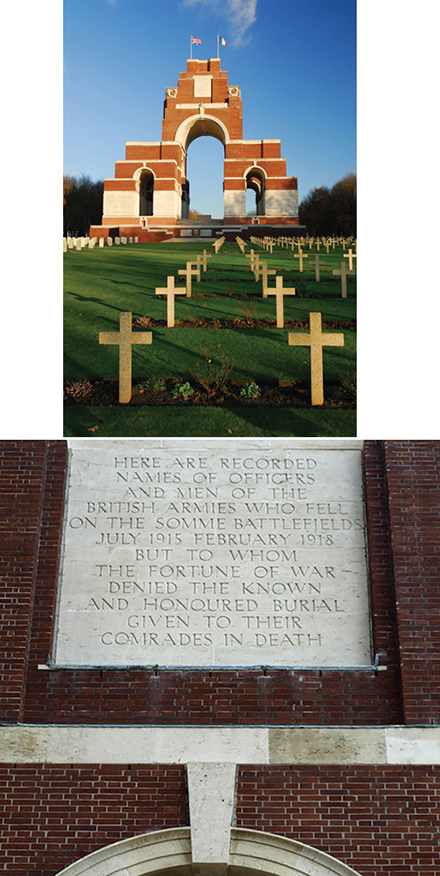

Plates 28 and 29. Sir Edwin Lutyens’s “Memorial to the Missing of the Somme” (top) commemorated those whom “the fortune of war” denied “known and honored burial” (bottom). In front are the graves of three hundred French soldiers (crosses) and three hundred British soldiers (headstones).

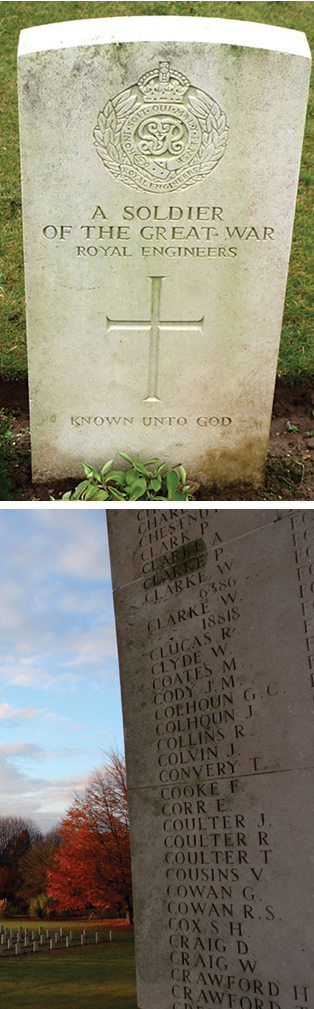

Plates 30 and 31. Each headstone commemorates a British soldier “Known Unto God” (top)—the French crosses state starkly “Inconnu” (Unknown). On Lutyens’s interwoven arches are inscribed the names of some seventy-two thousand British soldiers whose remains were never found.