3

WINDSOR

Birth of a dynasty

When Britain’s Queen Victoria married Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha on 10th February 1840, Saxe-Coburg-Gotha replaced Hanover as the name of the British royal family. The name change was automatic. Its most immediate effect was that Britain’s Queen and her future children could now proudly bear the family name of the man she loved — and in 1947 Philip Mountbatten assumed the same would happen when he and Elizabeth Windsor married. The Lord Chancellor of the time, Lord Jowitt, agreed. He examined the proclamation that had changed the royal family’s name to Windsor in 1917 and declared that it only applied to male heirs. The rubric did not mention female descendants, so, following the pattern set by Queen Victoria, the Princess and her issue should now take the name of her husband. For the five remaining years of George VI’s reign the young couple — plus their children when they arrived — were duly referred to as “the Mountbattens,” and the former Elizabeth Windsor was happy and proud to be known as Elizabeth Mountbatten. This remained the case after the Princess succeeded her father in February 1952. It is not always realised that Queen Elizabeth II came to the throne as Elizabeth Mountbatten, and that for eight weeks it was quite true to say, as Lord Louis Mountbatten proudly boasted one night over dinner at Broadlands, “that the House of Mountbatten now reigned.” But as Episode 3 of The Crown reveals, that boast provoked a bitter backlash from Queen Mary and Winston Churchill. When the arguments were over, the reigning house of Mountbatten was no more and Queen Elizabeth II was a Windsor again, with the old name proving more powerful than people expected. “Windsor” was not just any family surname or title: it was a made-for-purpose brand identity that had been created by history — and by Elizabeth’s beloved grandparents, King George V and Queen Mary, one of whom remained alive in 1952 to defend what she had helped to fashion 35 years earlier.

As co-founders of the house of Windsor, King George V and Queen Mary (right) created a new royal brand with which other brands were keen to associate — and to the end of her life, Queen Mary fought to defend the invented identity that had been the saving of the Crown at a time of peril. Credit 31

“Windsor” had, at the outset, been the product of war — the Great War of 1914 whose official declaration George V, aged 49, had had to sign on 28th July 1914. “It is a terrible catastrophe,” the King noted in his diary that night, “but it is not our fault.” He and his wife threw themselves immediately into war work, with the King traveling to France that November to visit the troops. “I cannot share your hardships,” he told them, “but my heart is with you every hour of the day.” Queen Mary, meanwhile, vigorously encouraged voluntary sewing and knitting campaigns, only to discover that she was provoking unemployment — her prolific consignments of free socks and shirts led to women getting dismissed from mills and clothing factories. Perplexed, she turned for advice to a prominent trades unionist, Mary Macarthur, inviting her to Buckingham Palace — to the horror of her ladies-in-waiting — for a meeting that proved to be the first of many. “The Queen does understand and grasp the whole situation from a Trade Union point of view,” Macarthur reported back to her colleagues. “I positively lectured the Queen on the inequality of the classes, the injustice of it…Here is someone who can help and means to help!”

Queen Mary’s willingness to embrace the radical stemmed from the misfortunes of her youth. Her parents, Prince Francis and Princess Mary of Teck, were the laughing stock of the Victorian royal family, literally outcasts because they were driven abroad to flee their debtors — living “in Short Street,” as their industrious eldest daughter would put it in later life. Born in 1867 and christened “May,” the teenage princess took advantage of her parents’ exile in Florence in the 1880s to add Italian to the English, French and German that she already spoke.

1917. The Saxe-Coburg-Gothas don a new British uniform. “Do you realise,” Lord Rosebery congratulated the King’s private secretary who came up with the name, “that you have christened a dynasty!” Credit 32

When her parents came back to England, May expanded her studies to include history and the social problems of an industrial society, putting her interests into practice by visiting poor houses, asylums and ragged schools. Statuesque and strong-featured, Princess May of Teck would have made the ideal wife for any socially concerned European prince or aristocrat — if she had not been born of “morganatic” blood.

The morganatic marriage, die morganatische Ehe, was an aristocratic Germanic device to prevent a nobleman or woman passing on their nobility to a spouse of lesser rank, so-called because all that the lesser-born partner could receive from the marriage was the morgengeba, the morning gift or dowry on the day after the wedding. It was social inequality enshrined in law, since the dowry might involve money, jewelery or property, but carried no precedence or succession rights — thus preserving the “purity” of the family title, while also consigning the morganatic partner and their descendants to a permanently inferior social status. May’s morganatic taint came from her grandfather, a duke who had married a mere countess, thus disqualifying his descendants from marriage into many of Europe’s royal and noble families.

Queen Victoria, however, had no time for such continental snobberies. She had watched May mature through all her misfortunes in Short Street and she considered the earnest young woman, now 25, to be the ideally solid partner for her wayward grandson Eddy, the elder son of the future King Edward VII, and thus a future heir to the throne. When flu carried off poor feckless Eddy in January 1892 on the eve of his marriage to May, the family were, perhaps, less inwardly broken-hearted than they outwardly appeared — and who better to pass on to May’s care than the new heir in line, Eddy’s younger (and significantly less feckless) brother George? The young man duly proposed and was accepted, and the couple were married in the Chapel Royal, St. James’s, on 6th July 1893. This more-than-semi-arranged marriage of Georgie and May (they became George and Mary on his accession to the throne in 1910) produced a strong emotional bond, particularly under the strains of the war that the King took so personally. “Very often I feel in despair,” he wrote in one of the daily letters that he and his wife exchanged when their war duties took them apart, “and if it wasn’t for you I should break.” Mary responded warmly, but with regretful rebuke at her husband’s face-to-face formality: “What a pity it is,” she replied, “that you cannot tell me what you write, for I should appreciate it so enormously.”

Forty-four years old when he came to the throne, George V had spent much of his youth as a naval officer, and his stiff, quarterdeck upper lip was part of his style. Having sent his eldest son David to the Western Front, the King dispatched his second son Bertie to a succession of postings on naval warships where the young midshipman — checked off daily as “Mr Johnson” on the ship’s roll call — learned to shovel coal, sling his hammock in the communal mess room, and eventually saw action in a gun turret at the Battle of Jutland in the summer of 1916.

In London, Queen Mary was seeking to fashion her own response to the appalling toll of war. Jutland had seen 6,000 British deaths in a single battle; 57,470 had died on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 1st July — more than had been killed in the Crimean and Boer wars put together. That August colourful “street shrines” started appearing on the brick walls of terrace houses in the East End of London, folk memorials created by locals to honour those from the neighbourhood who had lost their lives.

The names of the local casualties were framed by flags, flowers and ribbons, as well as by pictures of military leaders and members of the royal family. When Queen Mary appeared in Hackney that August, walking quite informally and with no obvious security from shrine to shrine, huge crowds gathered to cheer. The Queen bowed her head and laid a posy beside each of the ten rolls of honour, talking at length to those who had gathered in grieving. Men and women wept openly. It was difficult to imagine any princess of Germany, Austria or Russia getting such a warm and welcoming response from their people — if, indeed, any of them would have dreamed of mingling with their subjects in the street.

But events in faraway St Petersburg changed the tone. “Bad news from Russia,” noted George V in his diary on 13th March 1917, “practically a Revolution has broken out in Petrograd.” Two days later came the news that his cousin Nicky, Tsar Nicholas II, had been compelled to abdicate: “I am in despair.” The Russian Revolution struck a chill into monarchies all over Europe. Within 18 months, two other emperors had vanished, along with eight ruling sovereigns — all victims of military defeat — and even the monarchies of victorious countries felt the difference: “I have noticed, since the news came to hand of the Russian revolution,” noted Colonel Unsworth, a Salvation Army officer from Essex, ‘a change has come over a certain sector of the people in respect to their attitude towards the King and the royal family. In the streets, trains and buses, one hears talk…A friend of mine saw written in a second-class railway carriage, ‘To hell with the King. Down with all royalties.’ ” Railway second-class carriages were the equivalent of business class in aeroplanes today. So, Unsworth was wondering, might the slogans in the third-class carriages be even more disloyal?

August, 1916. Queen Mary visits Hackney’s “street shrines,” folk memorials created in London’s poorest areas to honour locals killed in the war. The Queen bowed her head and laid a posy beside each. Credit 33

In June 1917 George V’s financial adviser, Lord Revelstoke, wrote to the King’s private secretary, Lord Stamfordham, suggesting that the King should be better briefed on the anti-monarchical and republican sentiment in the country — to the indignation of the private secretary. “I can unhesitatingly say,” he responded, “that I do not believe there is any Sovereign in the World to whom the truth is more fearlessly told by those in his immediate service, and who receives it with such goodwill — and even gratitude — as King George. There is no Socialist newspaper, no libellous rag, that is not read and marked and shown to the King if they contain any criticisms, friendly or unfriendly, of His Majesty and the Royal Family.”

The truth of Stamfordham’s claim resides today in the Royal Archives, in a file entitled “Unrest in the Country.” Inside are the carefully marked articles from radical publications — and the project went beyond clippings. Stamfordham assembled a “floating brains” trust of experts who were felt to have their fingers on the pulse of the country. Part intelligence network, part think tank, their deliberations and reports are also included in the files.

One such gathering took place at the end of April 1917 when the chief talking point was an inflammatory letter that the novelist H. G. Wells had sent to The Times calling for the creation of “A Republican Society for Great Britain,” designed to show that “our spirit is warmly and entirely against the dynastic-system that has so long divided, embittered, and wasted the spirit of mankind.” In a much-quoted exchange, Wells had made no secret of his contempt for George V’s “alien and uninspiring court” — to which the King had famously retorted, “I may be uninspiring, but I’ll be damned if I’m an alien.”

The word “alien” hit a particularly sensitive spot in the spring of 1917. The Zeppelin airships that had erratically bombed East Anglia and Sandringham in 1915, creating Wolferton Splash, had been supplemented by a far more formidable threat — heavily armed German “battleplane” bombers manufactured by the Gothaer Waggonfabrik factory that was located, of all places, in Gotha, the southern section of the duchy from which the British ruling family took their name. The first Gotha bombing raid killed 95 people in and around Folkestone on the south coast in Kent, with a June raid on London killing 162, and in the next 16 months Gotha battleplanes would carry out a total of 22 raids on England, dropping 186,830 pounds of explosives. But the numbers were less important than the popular bewilderment that this dreadful destruction should be raining down from enemy aircraft that bore part of the King’s family name.

The issue of the royal family’s Teutonic origins and links had been on the agenda since the beginning of the war, when Dickie Mountbatten’s father, Prince Louis of Battenberg, had been hounded from the admiralty by the witch-hunt against all things Germanic. But with the arrival over London of the Gotha battleplanes, the issue became serious, and Stamfordham discussed the problem with another member of the “Unrest in the Country” think tank, the former prime minister Lord Rosebery.

In a letter of 15th May, Stamfordham had come up with an idea of an English surname — “Tudor-Stewart” was his suggestion — that could be used by the entire royal family, Battenbergs and Tecks included. At a meeting two days later, Rosebery suggested “Fitzroy,” and over the weeks that followed “Plantaganet,” “York,” “Lancaster” and even “England” were canvassed. After some discussion, the Tecks (Queen Mary’s family) and Battenbergs chose to go their own way, the Battenbergs becoming Mountbatten while the Tecks became Cambridge, leaving Stamfordham with the dilemma of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. Pondering all the alternatives one day — he was said to have been looking out of the window at the famous Round Tower at the time — the private secretary hit upon “Windsor.” It clicked immediately. “Do you realise,” Rosebery congratulated him, “that you have christened a dynasty!”

It was an extraordinary leap of imagination. Just saying the word “Windsor” conjured up the benevolent solidity of the stone Round Tower rising on the mound first built beside the Thames by William the Conqueror. No monarchy in history had done as such before. Newcomers and usurpers had taken over old names. But for an ancient clan coolly to reinvent itself with a fresh identity plucked from the air reflected hard-eyed realism — plus a certain measure of fear. On 17th July, the Privy Council announced the change, along with the royal family’s renunciation of all “German degrees, styles, dignitaries, titles, honours and appellations.” A new dynasty had been created to meet public demand. The decree gave no explanation for the reinvention, but the reason was obvious, and would become the guiding principle of the new House of Windsor — survival at any price. In Germany, the Kaiser remarked that he was looking forward to the next performance of “The Merry Wives of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.”

George V, Queen Mary and their “Unrest in the Country” advisers had understood the changes that mass industrialisation had wrought. The still-feudal monarchies of Germany, Austria and Russia, with their morganatic marriages and class-based barriers, saw themselves as the summit of a social pyramid in which the monarchy stood on the shoulders of the nobility, below whom were stacked the merchant middle classes, with the common people below that. Hierarchy mattered.

It was Stamfordham’s analysis — and the instinct of the King and Queen — that hierarchy was out of date. They had the same vision, in fact, as Karl Marx — that power in the modern world lay at the true foundation of the pyramid, with the people.

“Are we going to keep the king?” a left-wing activist had asked at a socialist summer camp in 1913. “Of course, we are,” came the answer, displaying the wobbly logic of which both socialists and monarchists are capable. “In England, the King does what the people want. He will be a socialist King.” A still more emphatic answer came at the Labour Party conference a few years after the war in 1923, when votes were invited on the proposition “That the Royal Family is no longer necessary as part of the British Constitution.” Three hundred and eighty-six thousand votes supported the motion; 3,694,000 voted against. General affection for the monarchy survived across Britain through the 1920s and 1930s, little shaken by the hardships of the Great Depression, and on 6th May 1935 the Silver Jubilee of George V’s 25 years on the throne was marked by celebrations all over the country. A spectacular panoramic oil painting by Frank Salisbury of the royal family entering St. Paul’s Cathedral for the service of thanks presented the latest iconography of the Royal House of Windsor, which featured by that date the little princesses Elizabeth and Margaret Rose. The girls were taken out on the balcony of Buckingham Palace at the end of that day for their first experience of the crowds surging and cheering in their thousands against the Palace railings, in spontaneous acclamations that swelled up every night for the rest of the following week. “I had no idea they felt like that about me,” declared the 69-year-old King. “I’m beginning to think they must really like me for myself.”

This was the history that fuelled the outrage of the 84-year-old Queen Mary early in February 1952, when Ernst August of Hanover brought her the news of Louis Mountbatten’s toast down at Broadlands to the new reigning “House of Mountbatten.” She angrily summoned Jock Colville, Churchill’s private secretary, to take instant action, and the prime minister responded at a cabinet meeting that same day. Churchill shared the old Queen’s historical memories and indignation. There were war criminals and German finance contributions to discuss, but to the very top of the agenda for 18th February 1952 went “Name of the Royal Family.” “The Cabinet’s attention was drawn to reports that some change might be made in the Family name of the Queen’s Children and their descendants,” read the cabinet minutes. “The Cabinet was strongly of the opinion that the Family name of Windsor should be retained, and they invited the Prime Minister to take a suitable opportunity of making their views known to Her Majesty.”

Within two days Churchill had passed on the government’s unanimous verdict to the Queen — provoking a domestic explosion. “Philip was deeply wounded,” recalled his naval comrade Mike Parker 50 years later, still shaking his head at the memory of the ructions that ensued. “I’m just a bloody amoeba,” the injured husband famously complained. “I’m the only man in the country not allowed to give his name to his children.” Philip sat down immediately to write a paper arguing his case, and also suggesting a compromise — that his children might take the name of Edinburgh and that the royal house might now be known as the House of Windsor and Edinburgh. Churchill was unimpressed — in fact, he flew into a rage when presented with the paper. He instructed the Lord Chancellor, the Lord Privy Seal, the Home Secretary and the Leader of the House of Commons — the biggest legal guns in his government — to spend two long meetings with Colville stamping every breath of life out of Philip’s proposals.

The grievance would rumble on for years. The Conservative politician R. A. Butler later said that the only time he saw the normally equable Elizabeth II close to tears was when confronted by the troubled issue of the family surname. But in the short term the issue was settled by a proclamation of 7th April 1952 declaring the Queen’s “Will and Pleasure that I and My children shall be styled and known as the House and Family of Windsor, and that My descendants, other than female descendants who marry and their descendants, shall bear the name of Windsor.” The proclamation had been prepared and taken to the Queen’s study in Buckingham Palace by her private secretary “Tommy” Lascelles, a confirmed pro-Windsor and anti-Mountbatten man, and as Elizabeth II bent her head to sign the document, he later related with grim satisfaction, he stood over her like “one of the Barons of Runnymede.”

(1887–1981)

PLAYED BY PIP TORRENS

“He is the most attractive man I have ever met,” declared Alan “Tommy” Lascelles (pronounced to rhyme with “tassels”) as he joined the staff of Edward, Prince of Wales in 1921. Eight years later, Lascelles resigned in disgust at his master’s incorrigible womanising and neglect of his royal duties, and his sense of betrayal infused the rest of his career with a dark and holy anger. Lascelles fumed in his diary against Edward VIII as “the most tragic might-have-been in history,” and even when he located the principles that he valued in George VI and his daughter, he saw himself as more their tutor than their Private Secretary (1943–52 to the king, 1952–53 to Elizabeth II). It was for Lascelles to teach them their job and enforce the Faustian bottom line of modern monarchy: that kings and queens must “abide by the rules of conduct expected of them by those who put them there,” since those who put them there are the people who pay for them.

(1867–1953)

PLAYED BY EILEEN ATKINS

“I played with Lilibet in the garden making sand pies!” wrote Queen Mary delightedly in her diary for 14th March 1929. “The Archbishop of Canterbury came to see us and was so kind and sympathetic.” Less than three years old, the future Elizabeth II was already learning lessons from her grandmother who, as co-founder with George V of the House of Windsor, helped develop the blend of grandeur with accessibility that lies at the heart of the modern popular monarchy. Queen Mary taught her granddaughter the value of an upright posture; the helpfulness of high heels and fancy hats for a lady of limited stature; and the over-arching importance of putting Crown before self. She also passed on a special Windsor trick for dealing with over-intimate remarks and presumptuous questions: to keep smiling levelly at the perpetrator as if you are hearing absolutely nothing — then move on smartly.

The Duke and the Cry Baby

“What a smug stinking lot my relations are…You’ve never seen such a seedy worn out bunch of old hags…” Whenever family business brought him to London, the exiled Duke of Windsor liked to let his feelings rip, and in February 1952 the notes that he wrote to his wife about the funeral of his brother George VI were especially direct: “Cookie & Margaret feel most.” (“Cookie” was the couple’s nickname for Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother). “Mama [Queen Mary] as hard as nails but failing. When Queens fail, they make less sense than others in the same state…

“Mountbatten. One can’t pin much on him but he’s very bossy & never stops talking. All are suspicious & watching his influence on Philip.” The ex-King’s only kind words were for his niece the new Queen (“Shirley Temple” in the Windsor code) who invited him to lunch with her husband in Clarence House: “Informal & friendly. Brave New World. Full of self-confidence & seem to take the job in their stride.”

In Episode 3 of The Crown, Peter Morgan introduces the former King Edward VIII to the drama, starting with a flashback to his abdication in December 1936 — “A few hours ago, I discharged my last duty as King and Emperor” — while we watch the little princesses play unsuspectingly with their corgis and bicycles. Later in the episode we follow the Duke, played by Alex Jennings, as he arrives in London in February 1952, mingling his role at his brother’s funeral with his manoeuvrings to save the £10,000 annual pension that George VI had been paying him while he was alive. We see the Duke triumph on screen at the end of the episode, working out a deal with Winston Churchill that also helps resolve the impasse over the royal family name. In reality, the Duke of Windsor did not retrieve his £10,000 pension — Cookie and Mama made sure of that. But the dynamics of the plot are based on an intriguing strand of history: that Edward VIII was an old friend of Winston Churchill, and that Churchill nearly destroyed his own political career when he took the King’s side in 1936 and tried to save him from having to abdicate. The two men became close in the summer of 1919 when the 25-year-old Prince was due to deliver a speech at a banquet for the victorious Allied war leaders after the First World War. The 34-year-old Churchill, Secretary of State for War and Air in Lloyd George’s post-war coalition, sent the young man some speaking advice — that he should not feel ashamed to read out his speech, but that if he did go the written route, he should “do it quite openly, doing it very slowly and deliberately.” It would be better, of course, to memorise his text, or to speak with only glancing reference to notes, and in this event Churchill recommended creating an improvised lectern from the table glassware and crockery — a fingerbowl placed on top of a tumbler, with a plate on top of that as a mini-platform for your notes. “But one has to be very careful,” he warned, “not to knock it all over, as once happened to me.” In the event, the young Prince of Wales committed his 1919 speech to memory and delivered it entirely without notes — to Churchill’s approval. “You are absolutely right to take trouble with these things,” he wrote. “With perseverance, you might speak as well as anybody in the land.”

As abdication loomed 15 years later, Churchill instinctively took the King’s side. He was a royalist — “the last believer in the divine right of kings,” as his wife Clementine once put it despairingly. He was also a romantic, defending Wallis Simpson, Edward VIII’s much-reviled American sweetheart, to be “as necessary to his happiness as the air he breathed.” With pressure and publicity mounting in December 1936, the King turned to Churchill, long out of office but rebuilding his reputation through his sturdy opposition to German Rearmament and a founder member of “Focus,” a cross-party group that spoke out against Fascism. Churchill’s advice to the King was to play for time, hoping for some sort of solution short of abdication — a German-style morganatic marriage, perhaps, whereby Mrs. Simpson might become his wife, but not his Queen, renouncing royal status for herself or any children. This proposal received short shrift, not least from the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin. “Is this the sort of thing I’ve stood for in public life?” he asked disgustedly. Ernest Bevin was even firmer on behalf of the Labour Party: “Our people won’t ’ave it,” he said.

On Friday 4th December Churchill went to dine with Edward VIII in Fort Belvedere, the King’s castellated residence near Sunningdale on the fringe of Windsor Great Park. The King must keep up his strength, Churchill insisted with emotion. He suggested the King must see a doctor, and that he should on no account go abroad. Above all, the King must play for time and ask for as long as he needed to make up his mind — “there is no force in this country,” he declared, “which would or could deny it you.” Parliament would be debating the subject shortly, and Churchill felt confident that the so-called “King’s Party” would prevail. “Good advances on all fronts,” he wrote to the King the following day, claiming success with his lobbying activities. There were “prospects of gaining good positions and assembling large forces behind them.”

1919. Winston Churchill and the Prince of Wales share cigars and conversation after a luncheon party at the House of Commons to honour US airmen who had flown the Atlantic during the Great War. Credit 36

But Churchill had gravely mistaken the mood of the country. That weekend MPs canvassed opinion in their constituencies, and when they returned to Westminster on Monday they strongly backed the intransigence of Baldwin and Bevin. The King could not have it both ways — he would have to renounce Mrs. Simpson if he wanted to keep the throne. When Churchill rose to his feet in the Commons on Tuesday to plead the King’s cause, “filled with emotion and brandy” (according to one observer), he was brutally shouted down. The once-respected former minister begged his colleagues not to rush to judgement and to give the King more time — to be ridiculed by an overwhelmingly hostile House.

“It was,” wrote The Times the next day, “the most striking rebuff in modern parliamentary history.” Robert Boothby, Churchill’s loyal ally in his stand against Hitler, was devastated. “In five fatal minutes,” he wrote, the Focus crusade against appeasement had “crashed into ruin.” Like Violet Bonham Carter and Churchill’s other allies, Boothby was appalled by this latest “Churchillian” error in judgement. “No one will deny Mr. Churchill’s gifts,” editorialised the Spectator gloatingly, “but a flair for doing the right thing at the right moment — or not doing the wrong thing at the wrong moment — is no part of them…He has utterly misjudged the temper of the country and the temper of the House, and the reputation, which he was beginning to shake off, of a wayward genius unserviceable in council, has settled firmly on his shoulders again.” Staggered by the unanimous rejection, Churchill shuffled out of the Chamber humiliated. “What happened this afternoon,” wrote Boothby in fury to his former hero, “makes me feel that it is almost impossible for those who are devoted to you personally to follow you blindly (as they would like to do) in politics. Because they cannot be sure where the hell they are going to be landed next.”

In the days that followed, Churchill helped Edward VIII frame the eloquent words of the abdication speech that was now inevitable, and he also fought his friend’s corner in the deeply bitter negotiations over the pension that George VI reluctantly agreed to pay his brother. It was hardly surprising that when Britain’s desperate wartime situation eventually brought Churchill out of the wilderness, initially as First Lord of the Admiralty in 1939 and then into Downing Street in May 1940, George VI had his reservations — “I cannot yet think of Winston as P.M.,” he noted in his diary. And Churchill ruefully described in his memoirs how he had been “smitten in public opinion…It was the almost universal view that my political life was ended.” “I have defended you so many times,” says Churchill in Episode 3 to the Duke of Windsor. “Each time to my cost and in vain.”

There was much to recall when Churchill and the Duke of Windsor met again in London in the run-up to George VI’s funeral in February 1952, and the tears welled up in the old prime minister’s eyes. “Nobody cried in my presence,” the Duke reported home to Wallis. “Only Winston as usual,” prompting the Duke and his wife to devise and bestow another of their clever nicknames upon the great war hero — “Cry Baby,” which said more about them than it did about him. After a few glasses of brandy, the Duke liked to deliver an after-dinner parody of the Fort Belvedere meeting when Churchill had pleaded with him not to abdicate, complete with a spoofed-up Churchillian accent: “Suhrrr, we must fight…” As “Tommy” Lascelles wrote sadly in 1944, Churchill’s sentimental loyalty to the Duke was “based on a tragic false premise — viz that he [Winston] really knew the D of W, which he never did.”

1952

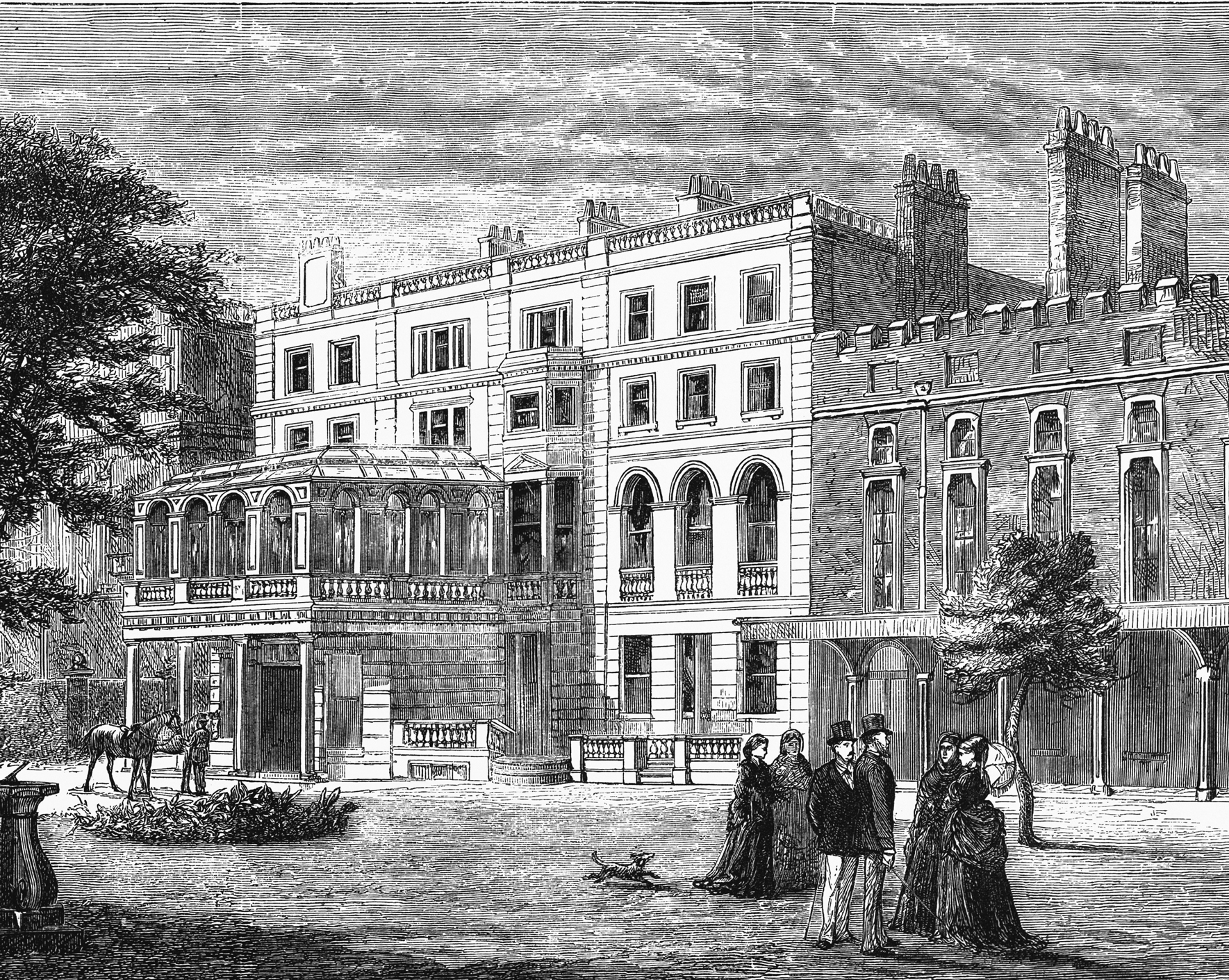

Clarence House is tacked on to the side of St. James’s Palace like a brightly iced Christmas cake. Designed and built by John Nash, the architect of Regency London, the white stuccoed mansion was the home of the Duke of Clarence, who later became King William IV (1830–37), and it has traditionally been the perch of retired royals or of royals-in-waiting: Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother lived there for nearly half a century until her death in 2002, to be succeeded by Prince Charles as he restarted his married life with his new wife Camilla. But early in 1952 Clarence House seemed destined for a higher purpose, as the principal home base of Queen Elizabeth II and her young family — a new perch for a new monarch, with the huge royal standard fluttering overhead. “Thank you for all this,” says Elizabeth at the opening of Episode 3 of The Crown, looking appreciatively around the renovations that her husband has been supervising. “It looks splendid.” “This is the first proper home I’ve ever had,” responds Philip contentedly, leaning down to kiss his wife’s cheek as the family breadwinner sets off on her daily commute to Buckingham Palace — no longer a royal residence, just a very grand office.

Lacking a single modern bathroom or a proper electrical system when the royal couple first inspected it in October 1947, Clarence House had emerged from the war in a mournfully derelict state, with bomb-damaged ceilings and a leaking roof. Lighting was provided by surface wiring on cleats tacked on to the wall by the Red Cross, the principal occupants after 1942, along with a temporary department of 200 Foreign Office civil servants concerned with the welfare of British prisoners of war. Parliament voted £50,000 for restoration, despite protests that the money could be better spent on public housing, and the work was completed in a speedy 18 months (and a cost overrun of £28,000), with Elizabeth and Philip visiting as often as twice a day. Elizabeth helped to mix the soft “Edinburgh Green” shade of paint for the dining room — “Put a bucket of hay in there,” she said when someone complained about the smell, “and that’ll take it away” — while Philip delighted in bringing back gadgets and labour-saving devices from the Ideal Home Exhibition. His office boasted the latest intercom, telephones and switchboard, along with a fridge for cold drinks, while his wardrobes could magically eject any uniform or shirt he wanted at the press of a button. The young Duke had picked up many of his ideas from his gadget-crazy uncle, Dickie Mountbatten, though he did not go in for the latter’s ultimate time-saving contrivance — a “Simplex” shirt with built-in Y-fronts.

An engraving of Clarence House around 1874, showing the large covered carriage porch, or porte-cochère, and how the white stucco building was connected directly to the red brick walls of St. James’s Palace on the right, with the two royal homes sharing the same long garden alongside the Mall. Credit 37

“The Duke” developed an unconventional reputation among the 11 staff, each of whom had their own carpeted bedroom and radio, and a “sleek, white, very futuristic television set” in the servants’ hall, a wedding present from the Mountbattens: word circulated that their boss did not own a single pair of pyjamas! “Never wear the things,” he said to one valet, while another reported him totally unembarrassed to be discovered one morning naked in bed with the Princess (who always wore a silk nightgown). Sir Frederick “Boy” Browning, Treasurer of the Duke’s Household, tracked the Duke down to the Palace pool across the road one day to find Philip giving his children swimming lessons stark naked. The Clarence House emphasis was on informality — light, serve-yourself lunches in the relaxed style that had impressed the Duke of Windsor on his 1952 visit, with casual dishes such as bangers and mash for supper. They almost lived like “ordinary people…” recalled John Gibson, the nursery footman in charge of polishing and pushing Prince Charles’s pram, “a lot less formal than some people I came across — people much further down the social scale.” Both Elizabeth and Philip loved playing with their children in the extensive garden that Clarence House shared with St. James’s Palace.

As the couple confronted the unexpected challenge of taking up their new royal duties in February 1952, both of them were attracted by the prospect of continuing to operate from their purpose-designed and cosy home base, defying tradition and the expectation of the royal establishment that they would move down the road to the grandeur of Buckingham Palace. Philip and Elizabeth decided that they did not, in fact, want to live “above the shop.” Staying in Clarence House would avoid the disruption of a move, and Philip, so happy in the up-to-date setting he had worked so hard to fashion, had developed a particular aversion to the cold formality of the Palace, headquarters of what younger courtiers called the “old codgers,” headed by “Tommy” Lascelles, whose disapproval he could sense. As a precedent, the very first occupant of Clarence House had continued living there after he became King William IV in 1830, strolling to work every morning next door in St. James’s Palace.

Philip set out his case in one of his naval-style position papers with the full support of his wife — and he was able to cite an unexpected ally. Queen Elizabeth, now the Queen Mother, was most reluctant to move out of her long-established quarters in the Palace, and her son-in-law developed this into a longer-term proposition. Looking only 20 years or so into the future, he argued, Prince Charles would require his own residence as Prince of Wales. As the annex to St. James’s Palace where so many subsidiary royal gatherings took place, Clarence House was the ideal HQ for the heir to the throne. It would be “blocked” if the lively and youthful Queen Mother were to be installed there — and that turned out to be precisely what came to pass. Thanks to the Queen Mother’s longevity, Prince Charles had to set himself up as a young man in the comparative remoteness of Kensington Palace, and did not move into the St. James’s Palace complex until 2003 — when he was well into his fifties.

But Philip’s pleadings cut no ice with Lascelles and the “old codgers,” who were emphatically supported by Winston Churchill. Buckingham Palace was the long-established focus of royal and national sentiment, insisted the prime minister, and the monarch had no choice but to live there. Elizabeth, Philip and their children went off to Windsor for their Easter holidays early in April 1952, and when they returned to London it was to move into Buckingham Palace — only a few days after the proclamation that had affirmed the enduring primacy of the House of Windsor. In the course of a few months, the Duke of Edinburgh had lost three of his young life’s most cherished components — his naval career, his family home and his family name. It did not make for a happy husband.

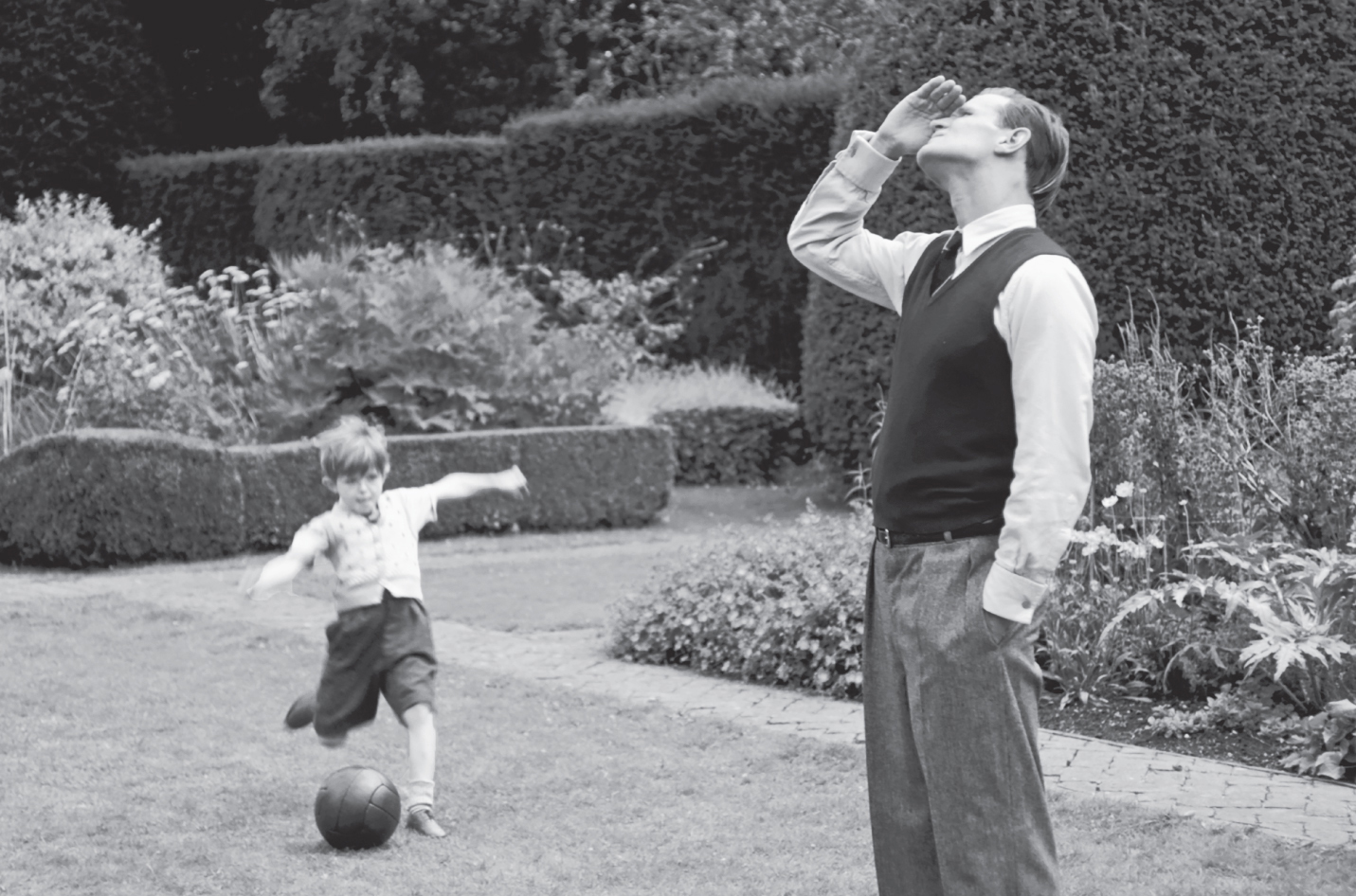

Renovated at a cost of £78,000 in 1948–49, Clarence House became the home base of Princess Elizabeth, the Duke of Edinburgh and their two children, Prince Charles, aged 2, and Princess Anne, aged 1, photographed in the garden after their parents’ return from Malta in the summer of 1951. Credit 38