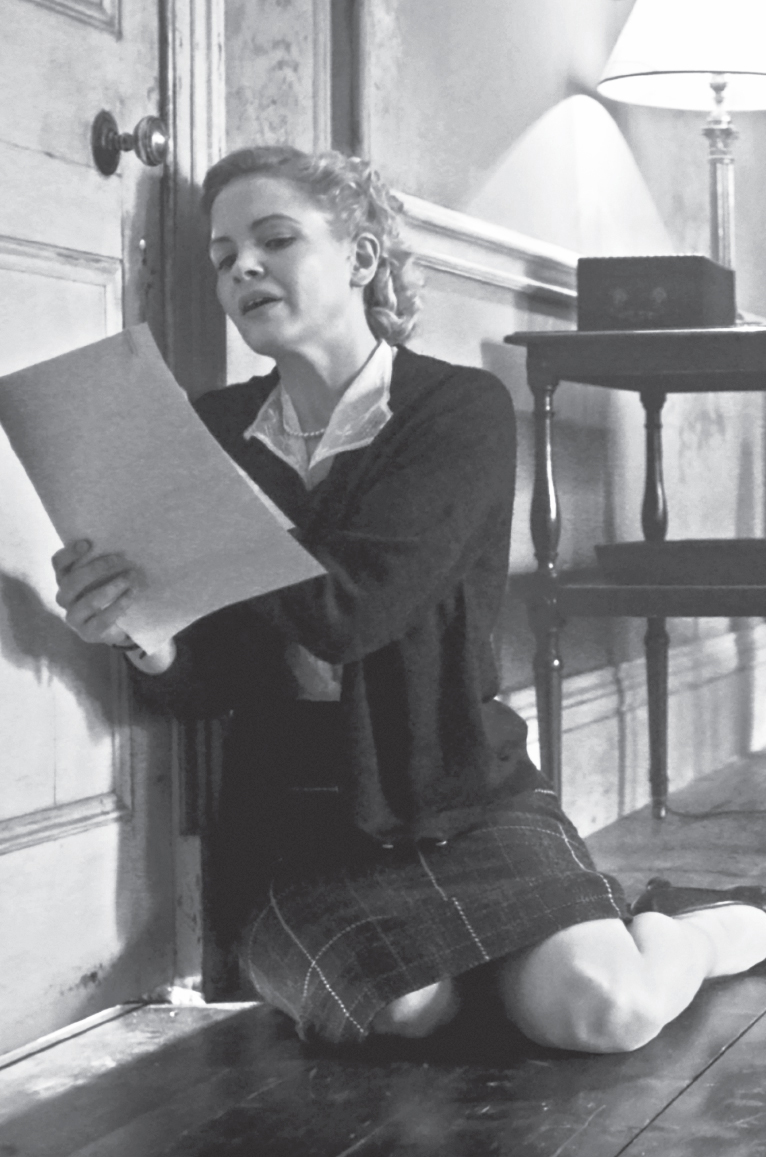

On the face of it, there is as much invention as history in Episode 4 of The Crown, “Act of God.” The principal catalyst in this episode, Venetia Scott, Winston Churchill’s attractive young secretary who gets killed by a bus, never existed. In the early days of December 1952, the “Great Smog” was not experienced as a life-and-death crisis by Londoners long inured to the routine of their winter “pea-soupers.” Nor did Clement Attlee and the Labour Party seek to bring down the Churchill government for its handling of the issue. On the other hand, the heroic Venetia Scott is a carefully researched, true-to-life-and-spirit composite of the remarkable team of women who worked so devotedly for Churchill in Downing Street. The “Great Smog” (the word was a combination of “smoke” and “fog” first coined by newspapers in Edwardian times) did eventually prove the catalyst for Britain’s first clean air legislation. And as for Labour not attacking Churchill more strongly, they didn’t need to. The ageing leader was undermined by the treachery of some of his own closest cabinet colleagues. Marion Holmes was the youngest of Churchill’s secretaries, 22, fair-haired and blue-eyed, according to one of her Downing Street colleagues, “like a fairy” — the most obvious physical model for Venetia Scott. “That’s a damned pretty girl — lovely,” Churchill once remarked to his guests at Chequers (the country residence of British prime ministers), while Marion was out of the room fetching a whisky and soda. “The sort of girl who’d rather die than have the secrets torn out of her.” “Oh dear, she’s very young,” he said on another occasion to his wife Clementine. “I mustn’t frighten her.”

Londoners learned a new word — and developed new health precautions, when the Great Smog struck in December 1952. This was a new type of struggle for which the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, was ill-prepared…Credit 64

Fully aware of the knee-quaking effect that his tantrums could have on others, the irascible prime minister tried to adopt a paternal attitude towards the team of half a dozen or more young women who made up his typing pool. Working on a continuous shift and relay system, his secretaries would take his dictation from 8.30 in the morning, while he was having his breakfast — usually in bed — until well after midnight and into the small hours, often in his dressing gown. “You must never be frightened of me when I ‘snap,’ ” he once told Marion Holmes. “I’m not thinking of you. I’m thinking of the work.” Holmes found that Churchill might suddenly go silent, then launch into a long strand of dictation without any warning, unaware of everything and everyone around him as he stalked up and down. He might sound out one tricky phrase to himself as many as 20 times sotto voce, going around and around with it until he got it right — often with the help of a glass of brandy or his beloved Pol Roget champagne. “You can’t make a good speech writer on iced water,” he used to say.

Whenever the prime minister cleared his throat, his secretaries knew they had to get their pencils out and start scribbling their shorthand (they might easily get through an entire notebook in a single session), or else locate one of the so-called “silent” typewriters that was always nearby and try to type out the words as they flowed. When Churchill returned to Downing Street in 1952, he moved his bedroom upstairs and reserved the room across the hall for his personal secretaries. “Girl!” he would shout from his bed, and one of them would come running with her pad and pencil at the ready. “Give me!” was his abrupt instruction when he considered the current document finished, and he would reach out to take the paper as it was peeled off the roller. After the briefest of breaks to look over the words, he would start dictating again.

Phyllis Moir, who joined Churchill’s staff in 1932, was the first secretary to document the strange ordeal experienced by Venetia Scott in Episode 1 — taking dictation while her boss splashed around in the bath. The dictating was always done with relative propriety, with the orator’s tones being broadcast through a slightly open bathroom door. But occasionally the prime minister would stalk out into the corridor with a towel draped round his expansive midriff, still loudly declaiming the speech he was due to deliver somewhere that evening. Staff took it in their stride in Downing Street, but the rotund and dripping spectacle stalking down a corridor at full volume would “scare the wits” out of unsuspecting housemaids in country houses, according to Moir, when Churchill went away for the weekend.

During the war his energies never seemed to relent, with dictation continuing full flow on some occasions until 4.30 in the morning. Working for Neville Chamberlain, Churchill’s predecessor in No. 10, Marion Holmes had been accustomed to stopping work every day at 6pm. But when Churchill arrived in May 1940, she wrote in her diary, “it was as if a superhuman current of high-voltage electricity was let loose.” The new PM seemed to relish the blizzard of official papers generated by any crisis, processing each document on the spot and sending it onwards, usually garnished with one of his specially printed red labels demanding “Action This Day.” “We must go on and on like gun horses till we drop,” Churchill told Elizabeth Nel, who joined his staff in 1941 at the height of the Blitz.

Transportation caught the smog headlines to start with — the stories of people sitting on the bonnets of cars or walking in front of them to give directions to drivers. London airport was shut down and air travellers had to travel more than a hundred miles to catch their flights in Bournemouth. Credit 65

“Fool,” “mug” and “idiot” were some of the gentler words that the prime minister flung at Nel’s head when she mistakenly typed her first memo single-spaced, not with the double spacing that no one had told her he preferred. If frustrated, Churchill would actually stamp his feet like a small child, but the recruit came to accept his frequent “snaps” as part of the grander project of which she was part. “Good heavens,” he once said to Nel when he thought he had made her cry, “you mustn’t mind me. We’re all toads beneath the harrow, you know.” (The line was Rudyard Kipling’s, an allusion to the heavy grid of spikes drawn by farmers across their fields to aerate the soil, doing for any wildlife caught in its path.) Delivered with a cherubic smile, his contrition was irresistible — along with his compelling sense of mission. “One would have the feeling,” Nel recalled, “of sharing a tremendous experience with him.” It was this same sense of purpose and urgent loyalty towards her boss that drew the fictitious Venetia Scott to step out into the smog in “Act of God” — only to be knocked down and killed by a bus.

While Venetia herself was fictional, her fate was not uncommon in London’s era of the “pea-souper.” On 7th December 1952 two railway workers repairing tracks near Norwood Junction, south London, were killed by a suburban train that failed to see them in the fog. The next day, two busy commuter trains were unable to see the warning signals and collided near London Bridge. With 38 ambulances out on emergency calls at one stage, London buses were ordered off the streets, crawling back to their depots in nose-to-tail convoys. But the severest fatalities resulted from the sick and elderly breathing in the toxic fumes and dying at home or in hospital. A windless anticyclone over London had trapped the smoke from the city’s coal-burning power stations, blending smoke particles, carbon dioxide, hydrochloric acid and, most lethal of all, some 400 tonnes of sulphur dioxide (as was later calculated) into a deadly cocktail whose principal ingredient was sulphuric acid.

The chemicals came from the low-grade coal burning in the grates and boilers of almost every home in those days before the advent of oil- and gas-powered central heating, and especially from the coal-fired electrical power stations whose towers loomed along the Thames — at Fulham, West Ham and, most substantially, at Battersea. A few hundred yards down the river from Westminster, the four huge towers of the massive Battersea Power Station sprayed out the largest exhaust output of all, so it was no coincidence that Westminster was heavily showered with yellowish black flakes of soot and grit — part oil, part mud — that caused a stinging sensation in the eyes and the lungs. “The fog itself swirled into the wards and seemed to consist principally of smuts,” recalled Sir Donald Acheson, later Chief Medical Officer of the United Kingdom, then a young doctor at the Middlesex Hospital near Tottenham Court Road, “so that the wash basins and baths turned darker and darker grey, until it was literally possible to write one’s name on them — which I actually did.” The wards of the Middlesex started to fill with middle-aged and elderly patients with breathing difficulties, and after one or two days the young medic called the senior surgeon asking for permission to cancel all routine operations and admissions from the waiting lists. All the available surgical wards, and even the obstetric wards, were filled to overflowing with patients who were displaying the most acute respiratory distress.

Labour Prime Minister

(1883–1967)

PLAYED BY SIMON CHANDLER

“Citizen Clem” was the longest serving leader of the Labour Party and the architect of Britain’s “cradle-to-grave” welfare state. Charitable work in London’s East End turned the 23-year-old ex–public schoolboy into a social reformer dedicated to alleviating poverty through state intervention and the redistribution of wealth — “a right established by law, such as that to an old age pension, is less galling than an allowance made by a rich man to a poor one.” Thrice wounded in the First World War, he was a patriot who did not let his socialist principles prevent him building the free world coalition against Stalin in the 1940s, nor secretly developing Britain’s own nuclear deterrent. Slight, reticent and pipe-smoking, Clement Attlee was tap water to Winston Churchill’s champagne — a bank clerk to the dog of war. But the nation and the egalitarian consensus he shaped between 1945 and 1951 made him Britain’s greatest ever peace-time prime minister.

This is the scene depicted so graphically in “Act of God,” but it was not the angle projected by the media at the time. Transport problems caught the main headlines — the stories of people sitting on the bonnets of cars or walking in front of them to give directions to drivers, and the closing of London airport. To catch their flights, travellers had to journey from the capital down to Hurn airport near Bournemouth by train — drawn by one of the country’s 19,000 coal-fired steam locomotives that were only exacerbating the smog problem. Shipping was halted on the Thames, and drivers abandoned their vehicles in the street to walk to work. “London has never seemed so empty of traffic since the war years when petrol was drastically rationed,” reported the Manchester Guardian.

The cancellation of every sporting fixture in south-east England caught the headlines on the weekend of 6th and 7th December. Britons were “passionately addicted” to their football, reported the New York Times: the dog and horseracing tracks were shut down — and even cinemas were affected. “Screen visibility nil” warned one manager on a notice outside his theatre; the film could only be seen from the very front rows. On 8th December, the audience at the Royal Festival Hall on the south bank of the Thames found that the extra-thick river fog meant they could not see the stage at all. Much worse, and the subject of numerous lurid headlines, was the increase in what the Guardian described as “footpad crime and burglary…The smash-and-grab-men are harvesting fast. The smog made it impossible for the information room at Scotland Yard to direct area wireless cars to 999 calls, and the police are having to use pedal cycles.” When it came to fatalities, the deaths that first caught the headlines were the demise at the Smithfield Show of 11 prize cattle suffering from breathing difficulties, eight of them slaughtered at their owners’ request: “the smoke-laden air of London has proved especially harmful to those cattle from areas where the air is normally cold but dry.”

It was only after winds had dispersed the smog on 10th December that the facts about human illness and death began to be realised, and when the figures were tallied they came as a shock. On 18th December 1952, the health minister Iain Macleod reported to the Commons that deaths in Greater London had more than doubled in the week ending 13th December — to 4,703 as compared to 1,852 in the corresponding week of 1951, and that “a large part of these increases must be attributed to fog.” A second smog of the month on 27th December, with acrid white clouds swirling through the streets and seeping “into houses gay with Christmas season decorations,” finally brought home the gravity of the situation — with more deaths in the capital, reported the Lancet, than the fatalities from the disastrous cholera epidemic of 1886. “Massacre” was the headline in Lord Beaverbrook’s Evening Standard, which pointed out how December’s full death toll of some 6,000 Londoners matched the 5,957 killed by Nazi bombers in September 1940, the worst month of the Blitz. “The economic loss — from grounded airplanes, dirt and slowed commerce — runs into millions of pounds,” reported the New York Times “…Many Londoners, coughing and feeling vague chest aches, are experiencing a feeling of fright.” From shrugging its shoulders a few weeks earlier, the Churchill government announced that it was now treating the recurring smogs as “a problem of the very greatest urgency” — the 180-degree change of direction that “Act of God” dramatises as being provoked within days by the death of Venetia Scott.

Clement Attlee was tap water to Winston Churchill’s champagne — a bank clerk to the dog of war. But for fifteen years, from 1940 to 1955, the two men took it in turns to occupy 10 Downing Street, and were closer friends than they allowed the world to know. Credit 67

Once the facts were known, the process of enquiry and legislation that led to the Clean Air Act of 1956 was relatively bipartisan, reflecting a respect and even affection between Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee that was deeper than the outside world guessed.

Churchill’s supposed jibes about the man who defeated him for prime minister in 1945 were well known: “a sheep in sheep’s clothing”; “a modest man who has much to be modest about”; “an empty taxi drove up to 10 Downing Street, and out of it stepped Clement Attlee.” But not all these sneers can be traced back to Churchill, and in private he would often defend his laconic opponent as a patriot — “a faithful colleague who served the country well at the time of her greatest need.” He was referring to the bitter debates inside the Inner War Cabinet on the evening of 28th May 1940 following the ignominious retreat of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk, when Britain stood alone in what would become known as her “darkest hour.” Neville Chamberlain and Edward Halifax were urging that some sort of peace deal now had to be attempted with Hitler, outshouting Churchill two to one, until Attlee and his Labour colleague Arthur Greenwood weighed in. The mere suggestion of surrender talks would shatter national morale, they argued, and Churchill never forgot Attlee’s staunchness in what Peter Hennessy has described as “the most crucial two hours in modern Cabinet history.” Even as the rivals later tussled over political issues such as nationalisation and the nature of welfare provision, Churchill would regularly praise the solidity with which the Labour leader — “an honourable and gallant gentleman” — had served as his loyal and highly efficient deputy in the Coalition cabinet that eventually won the war.

After the war, Churchill was surprisingly accommodating towards many features of the “Socialist Commonwealth” that Attlee’s Labour government implemented in the years between 1945 and 1951. Thirty years later, radical Conservatives of the Margaret Thatcher era looked back with surprise and regret that when Churchill regained power in October 1951 he had not sought to reverse more aspects of Labour’s welfare state — especially the nationalising of transport and energy. But Churchill was never a “Tory” in the hard-line sense — “I am an English Liberal,” he wrote in 1903. “I hate the Tory party, their men, their words and their methods.” He was proud to have introduced the first Unemployment Insurance Scheme as a Liberal frontbencher in 1908, and to have shaped and carried the Widows’ Pension and the reduction of the Old Age Pensions from 70 to 65 when he was Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1924. While criticising Attlee’s post-war agenda, Churchill came to accept its main framework as Britain’s equivalent of Roosevelt’s “New Deal,” and his offer to the electorate in October 1951 was not to abolish the welfare state, but to manage it more efficiently — “houses with red meat, and not getting scuppered.”

When the constituency count narrowly went his way, the re-elected prime minister did not minimise the challenge. “In the worst of the war I could always see how to do it,” he confessed to Oliver Lyttleton, his Secretary of State for the Colonies. “Today’s problems are elusive and intangible.” He struck a similar note in his tribute to Queen Mary following her death in March 1953. “It requires not only courage but mental resilience for those whose youth lay in calmer and more slowly moving times,” he declared, “to adjust themselves to the giant outlines and harsh structure of the twentieth century.” He might have been talking about the giant outline of the Battersea Power Station itself looming up in its angular ugliness out of the smog. Harold Macmillan, his minister of housing, had been partly responsible for the troubles of December 1952 by resisting calls for smoke controls the previous summer, and Macmillan subsequently obstructed the appointment of a commission of enquiry. But once the Committee on Air Pollution started its work under Sir Hugh Beaver in May 1953, progress was rapid. “Few reports into a social evil have led to such swift action,” wrote Brian Clapp approvingly in An Environmental History of Britain. Within ten years of the Clean Air Act becoming law in 1955, industrial smoke emissions had been reduced across the country by some 74 per cent and “smog” was a stinky relic of history.

Whatever their day-to-day political differences, Churchill and Attlee personally continued to treat each other with respect. Attlee and his wife Violet were invited to all major Downing Street events, both official and private, including Churchill’s eightieth birthday party in November 1954 and Clementine’s seventieth a few months later. Attlee was on better terms with the Conservative leader, in fact, than some of the leading members of Churchill’s own party, who had been trying to dislodge him for nearly a decade.

As early as 1945 a group of Conservatives led by Robert “Bobbety” Cecil (Viscount Cranbourne, later Marquess of Salisbury) had come up with a plan to put the old warhorse, by then 70, out to pasture in the House of Lords while remaining the nominal head of the party, thus allowing his deputy, Anthony Eden, to fight the day-to-day battles in the House of Commons. Eden was unwilling to push the issue in 1945, but seven years later, with Churchill closer to 80, Bobbety was still trying, and he saw his opportunity on the morning of Friday 22nd February 1952, when Charles Moran, the prime minister’s doctor, arrived in his office for a hastily summoned meeting convened by “Jock” Colville, Churchill’s private secretary.

Churchill had suffered a mild stroke the previous afternoon — an arterial spasm — Moran reported. When the prime minister awoke from his regular nap and picked up the telephone, he found his mind had gone blank, temporarily unable to summon any words to utter. He had since recovered his speech, but Moran could only foresee a recurrence of the problem — or worse — in the future. This was surely the moment, Salisbury proposed, for the PM to be moved gracefully “upstairs,” and the other men agreed.

They also agreed that only the Queen could propose such a drastic course of action to Churchill with any chance of success, so they arranged a meeting that very afternoon with Tommy Lascelles at Buckingham Palace. Lascelles concurred with the trio that a mentally impaired prime minister was a serious constitutional problem, and he felt that Bobbety’s plan to cajole Churchill sideways might stand some chance of success. But the private secretary adamantly refused to involve the Crown in the matter. He thought that the young Queen, not yet two full months in the job, had not the slightest chance of persuading the prime minister to step aside. If she did broach the subject, Lascelles speculated, Churchill would thank her courteously for her suggestion, then move on imperiously to other business — “It’s very good of you Ma’am, to think of it…” were the words that Lascelles suggested to Moran that Churchill might deploy. A botched intervention by the new monarch would damage both her prerogative and her relationship with her first prime minister — though it might have been different, added the private secretary, if King George VI had still been alive…

So, the old warhorse would stay in harness — until his next stroke, at least — though there is one caveat to make about Lascelles’ refusal to raise the question of Churchill’s possible resignation with the Queen in February 1952. Only a few days earlier, the private secretary and the prime minister had been conferring together — not to say plotting — to abort the ambitions of the Royal House of Mountbatten and to guarantee the preference of the “old codgers” in the Palace that the House of Windsor should continue to rule. One good turn deserved another. Lascelles’ preservation of Churchill inspired the semi-comical “non-intervention” scene that Peter Morgan depicts towards the end of “Act of God,” when Elizabeth summons her prime minister to question him on his handling of the smog crisis, only to change course and sidestep confrontation when she sees the sun miraculously breaking through the fog. “But what if the fog hadn’t lifted?” she asks her grandmother Queen Mary afterwards. “And the government had continued to flounder? And people had continued to die? And Churchill had continued to cling to power and the country had continued to suffer? It doesn’t feel right, as Head of State — to do nothing…Surely doing nothing is no job at all?”

ROBERT CECIL

(1893–1972)

PLAYED BY CLIVE FRANCIS

As a direct descendant of William and Robert Cecil, counsellors to the first Queen Elizabeth, and grandson of Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, Queen Victoria’s last prime minister, “Bobbety” Salisbury prided himself on his service to the monarchy, to the Church of England and to the Conservative Party. An early supporter of Winston Churchill in his fight against appeasement, he took a stand when he could see that the great man’s powers were failing — as he later took a stand against Princess Margaret’s wish to marry the divorced Peter Townsend. Much-imitated for his difficulty in pronouncing the letter “r,” Bobbety is remembered for the question he put to leading Conservatives in January 1957 when trying to discover whether they favoured “Rab” Butler or Harold Macmillan to succeed Anthony Eden as prime minister: “Well,” he enquired, “is it to be Wab or Hawold?”

“It is exactly right…” replies the elder woman, drawing on all the experience of her 43 years as Queen. “To do nothing is the hardest job of all, and it will take every ounce of energy that you have. To be impartial is not natural, not human. People will always want you to smile or agree or frown, and the moment you do, you will have declared a position, a point of view — and that is the one thing as Sovereign that you are not entitled to do. The less you do, the less you say, or agree, or smile…” “Or think? Or feel? Or breathe? Or exist?” interjects the young Elizabeth despairingly. “The better,” concludes her grandmother with firm and icy decisiveness. It was bitter advice, but Elizabeth II would follow it strictly for the rest of her reign, and the harsh truth it contained would see her safely, if not always happily, through many a foggy crisis ahead.

“Does the name Donora mean anything to you?”

As London’s meteorologists struggled to understand the combination of factors that had generated the Great Smog of December 1952, they had a model to hand on the other side of the Atlantic — the small industrial town of Donora on a collar of the Monongahela River, just south of Pittsburgh, in Pennsylvania steel country. For four days at the end of October 1948 a layer of stagnant air over the town had trapped the poisonous exhaust fumes of the Donora Zinc Works, along with the pollutants from local steel mills, slag dumps and a sulphuric acid plant, to create a noxious fog that killed 800 animals, sickened 7,000 humans and killed at least 20 people, who died following agonising, asthma-like breathing difficulties. Moved by the tragedy, President Truman convened a national conference of scientists and weather experts who came up with a relatively straightforward diagnosis and remedy — the need for stringent smoke control regulations, some of which were embodied in America’s first ever air pollution legislation, the Air Pollution Control Act of 1955.

This was followed by the Clean Air Act of 1963, which funded a federal programme to address air pollution reduction techniques, but, as in Britain, it took a major city disaster to stir up decisive action. At the end of November 1966, New York City’s Thanksgiving celebrations were overwhelmed by a smog that more than doubled the sulphur dioxide content of the air at street level. The city’s 11 municipal incinerators were shut down; landlords were asked to turn down apartment block thermostats to 60 degrees; Consolidated Edison and the Long Island Lighting Company limited their sulphur emissions by switching to natural gas from fuel oil; and state governor Nelson Rockefeller declared a “first alert advisory” to cover the New York metropolitan area, Connecticut and New Jersey. By the time the alert was lifted three days later, 168 deaths had been reported from respiratory distress.

By comparison to Donora and London, New York got off comparatively lightly from its smog. But one striking photograph from the top of the Empire State Building by Neal Boenzi of the New York Times had a dramatic effect on national sentiment, helping to inspire the Clean Air Act of 1970 and the establishing of the United States Environmental Protection Agency by Richard Nixon in the same year. In Donora, meanwhile, where the Zinc Works closed in 1957 with the loss of 900 jobs, followed ten years later by the US Steel facility with the loss of 5,000 more, a group of activists opened the Donora Smog Museum to commemorate the “folks [who] gave their lives so we could have clean air…We here in Donora say this episode was the beginning of the environmental movement.” On display inside the museum is one of the original oxygen tanks which firefighters carried round the darkened streets in 1948 to bring relief to gasping citizens, and outside is an orange sign that proudly proclaims, “Clean Air Started Here.”

Rainbow One

Over Whitsun weekend towards the end of May 1953, Mike Parker, the Duke of Edinburgh’s old naval comrade and now private secretary, found himself summoned to No. 10 Downing Street. There he was sent up to the prime minister’s office, where Churchill kept him standing in front of his desk for no little time before he deigned to look up from his papers. “Is it your intention,” he finally asked balefully, “to wipe out the royal family in the shortest possible time?” The prime minister had been horrified to come across a newspaper report of the Queen’s husband being transported to his pre-coronation engagements by helicopter, and wanted to know how such a risky method of travel had been adopted without the permission of Her Majesty’s Government. It was only after much reassurance as to the sterling safety record of the Royal Navy Helicopter Squadron — and the offer of a naval helicopter for the PM’s next trip outside London — that Churchill was even faintly mollified.

The prime minister had raised even more difficulties the previous October when confronted with the news that the Queen’s husband wanted to learn to fly, and he had made it a matter for cabinet discussion. He was worried about Philip’s own safety, but he was still more concerned that, once the young man had earned his wings, he might feel inclined to take his wife and family flying with him. Churchill’s younger colleagues tried to argue Philip’s case, pointing out that the late King himself had earned his wings as an RAF pilot — as had his brothers the Dukes of Windsor, Gloucester and Kent — and that flying “was now widely regarded as a normal means of transport.” Skating tactfully around the prime minister’s age (Churchill would be 78 the following month), they remarked how young men these days considered learning to fly “little more hazardous than learning to drive a motor-car.” Perhaps their strongest argument, in view of the recent cabinet decisions that had gone against the Prince, was that it would be “a great disappointment” if this young man’s personal wishes were frustrated. Churchill said he would take up the matter with the Duke on his forthcoming visit to Balmoral, and two weeks later he was able to report back that he had secured the necessary assurances — and particularly that HRH “had no intention of attempting to fly jet aircraft.” This had special resonance in the aftermath of the Farnborough Air Show disaster of the previous month, when a prototype DH110 jet had crashed into the crowds, killing 31 people. Most important of all, the Duke had undertaken not to pilot any plane in which the Queen was a passenger.

On reflection, the prime minister felt able to withdraw his objection to the Duke undergoing basic training as a pilot “under the guidance of a Royal Air Force instructor,” and the approval was duly minuted as Cabinet Conclusion 85 of 14th October 1952. Philip had always wanted to fly — “like all small boys,” as he once put it, “who want to drive railway engines.” As an adult, he came to see the exercise of piloting an aeroplane as “an intellectual challenge,” and, if he had had his way, he would have left school for a career in the Royal Air Force rather than in the Royal Navy. But Uncle Dickie had urged the cause of the navy as offering better family connections — and so it had proved, of course, in the most spectacular fashion.

One consequence of Elizabeth coming to the throne was that her husband was showered with high military ranks, among them Marshal of the Royal Air Force, and Philip decided that he could not morally accept that dignity without earning his wings as a pilot. The Crown shows Peter Townsend teaching Philip how to fly. In fact, the Duke’s instructor was Flight Lieutenant Caryl Gordon of the RAF’s Central Flying School, who took him up for his first proper lesson from White Waltham airfield near Maidenhead on 12th November 1952, and had him flying solo by Christmas. He rated his royal pupil as “above average,” though he admitted to being “perturbed” when he watched the Duke’s first solo spin “by the number of turns he completed before recovering.” Windsocks were set up in Windsor Great Park to turn the polo field at Smith’s Lawn into a landing strip, and Elizabeth brought Charles and Anne out to watch their father land his Chipmunk Trainer, then clamber up inside to inspect the cockpit — though not to fly off with him afterwards.

By February 1953 Philip had graduated to a more advanced plane, the Harvard Trainer, and an RAF examining unit described his flying as “thoughtful with a sense of safety and airmanship above average.” His navigation skills were outstanding, which was hardly surprising after his years of combat service in the navy, though Flight Lieutenant Gordon did have cause to lecture his charge on one occasion about the hazards of overconfidence — a lesson, he reported, that was received “with humility.”

On 6th May 1953 the Duke celebrated his newly awarded wings by flying solo over Windsor Castle. He loved flying, he later said, because it was totally consuming — when you are piloting a plane, you cannot think of anything else. Credit 71

On 4th May 1953, a month before the coronation and a few weeks before his thirty-second birthday, the Duke of Edinburgh was duly awarded his pilot’s wings by the Chief of Air Staff at Buckingham Palace in the presence of the Secretary of State for Air, the Captain of the Queen’s Flight and a very broadly smiling Queen. The family were due to travel to Balmoral next day for a brief pre-coronation break, and, while Philip decided he would fly himself up to Aberdeen, his wife and his children travelled separately.

“I feel very strongly,” Philip later wrote, “that flying isn’t a sort of black art which can only be done by devotees or daredevils.” He loved flying, he said, because it was totally consuming — when you are piloting a plane, he explained, you cannot think of anything else. As the Duke gained experience, it became quite routine for him to pilot all the aircraft of the Queen’s Flight with a co-pilot beside him — his call sign was RAINBOW ONE — and in that fashion he did fly his wife and children for many hundreds of hours, as he had once assured the cabinet that he wouldn’t. In 1956, he also took his first lessons in a helicopter and received his wings as a Royal Navy helicopter pilot. But by then Winston Churchill was no longer prime minister.