NEOLITHIC AND COPPER AGE MORTUARY PRACTICES IN THE ITALIAN PENINSULA

Change of Meaning or Change of Medium?

For Gianni Bailo Modesti – In Memoriam

The goal of this paper is to reassess the changes in mortuary practices documented in the Italian peninsula during the late 5th and 4th millennia BC, at the transition between Neolithic and Copper Age. For much of the Neolithic, burial was carried out within the nucleated village in the form of a relatively simple performance, which started with the interment of an articulated body and ended, in most cases, with the disturbance of the grave and the scattering of the dry bones. In the late and final Neolithic, however, burial was increasingly undertaken at peripheral or otherwise distinct areas within villages, and by the early Copper Age it was moved to purpose-built extramural cemeteries. Moreover, disarticulation practices became increasingly complex in this time period, and caused most of the deceased to lose their individuality. Finally, the Copper Age saw the appearance of the first richly furnished burials, which are often interpreted as markers of growing social inequality. It is argued in this paper that the emergence of the cemetery as a separate locus for the performance of burial does not depend on radical changes in the political structure of society. Rather, it would mark a profound modification in the symbolic toolkit used by prehistoric society to express individual and group identity as well as beliefs concerning the human body. In other words, it is not a change in the meaning of burial per se that we are witnessing in the Copper Age but a change in the medium chosen by society to stress overarching ideas of group identity, which were previously conveyed by co-residence in the nucleated village. However, since social relations derive their meanings from the practices through which they are articulated, modifications to the social understanding of burial did emerge from the changing media employed for their expression. The most important of these concerns the body of the deceased, which Copper Age communities turned into a major locus for social reproduction.

Keywords: body, burial, identity, Italy, mortuary practices, Neolithic, Copper Age.

Introduction: burial, politics, and identity

A central avenue of investigation in funerary archaeology claims that changes in burial rituals are to be explained with changes in the political structure of society. Explorations into the political aspects of burial were especially favoured by processual archaeologists in the 1970s and early 1980s. This tradition of studies can be traced back to Binford (1971), who famously maintained that burial directly reflects the structure of society, and that differences in funerary treatment are informative about power inequalities and social hierarchy amongst the living. He also argued that the social persona of the deceased, or the composite of a person’s social identities recognised as appropriate for consideration in death, would vary according to their lifetime rank.

Working within a similar research milieu, Tainter (1978) introduced the concept of energy expenditure into mortuary analysis. He claimed that the more energy is expended by mourners during all stages of the funerary performance – be it in the lavishness of the funeral, the monumentality of the grave or the quantity of goods deposited therein – the higher is the standing of the deceased within their community. In a similar vein, Saxe (1970) argued that cemeteries are established by corporate groups to legitimise their rights to access restricted resources, for ancestors provide a powerful medium to support political claims. Finally, O’Shea (1981) assessed the viability of mortuary data as an indicator of ‘vertical’ (i.e. hierarchy-driven) and ‘horizontal’ (i.e. descent-driven) social distinctions. By examining changes in burial patterns at a number of native cemeteries in the American Central Plains, he found that ranking would emerge quite clearly from variations in the mortuary record while the ‘horizontal’ dimensions of society would be more difficult to identify.

In the last three decades, these concepts have been applied to investigating the changes in funerary customs which occurred in the Italian peninsula during the late/final Neolithic and early Copper Age (c. late 5th and 4th millennia BC). Burial, in particular, was widely employed as a proxy for two major phenomena that were thought to characterise prehistoric Italian society at this important juncture: the rise of social ranking and the establishment of political claims over land or other restricted resources.

In numerous works dedicated to the Italian Copper Age, Cazzella (1992; 1998; 2003a) argued that the appearance of richly furnished burials would reflect the emergence of structural inequalities within prehistoric society. In particular, he interpreted the practice of burying adult males with rich sets of tools and weapons as a marker of a ‘Big Man’ society, in which men competed for power through the accumulation of prestige-giving goods. Since power could not be transmitted by descent in societies of this kind – he argued – the funerals of these individuals were marked by acts of conspicuous consumption whereby the symbols of their lifetime authority were removed from circulation. Thus, the burying of ‘Big Men’ would have sanctioned the opening of a new power contest within their communities. Similar readings were championed by Barker (1981), Guidi (2000), and Peroni (1989; 1996), and greatly contributed to shaping scholarly interpretations of Copper Age society in the central Mediterranean region.

With regard to the politics of resource procurement and land use, Skeates (1995: 229) noted that the earliest Copper Age cemeteries to be found in east-central Italy lay at the heart of the agricultural zone stretching through valley bottoms and coastal lowlands. Following Saxe (1970) and Bradley (1981), he proposed interpreting this evidence as the archaeological correlate of the political claims made by emerging elites over arable land and pastures. However, he tempered his reading by pointing out that graves in this period presented no exterior monumental aspects. Therefore, he argued, such claims might have had a rather limited outreach, and were perhaps intended more for the immediate funeral audience than for society at large. Notably, such interpretations were not solely put forward for the fertile valley bottoms of middle Adriatic Italy, but were also extended to the rugged landscape of southern Tuscany and northern Latium, where arable land is historically scarce. For example, it was suggested that Ponte San Pietro, a Copper Age cemetery in this region, had been purposefully established near now-depleted copper and antimony deposits, perhaps as a way to claim access to critical ore sources (Giardino et al. 2011). The fortune of such readings is most apparent in a recent synthesis of research on the Italian Neolithic, in which the rise of corporate burial in the 5th millennium BC is ascribed to the need to legitimise control over valuable resources by placing the dead in the landscape (Pessina & Tiné 2008: 304).

The limits of these approaches, which tend to equate funerals with a social arena for power contests, have been revealed by an alternative tradition of mortuary analysis stemming from contemporary social theory (Bourdieu 1977; Giddens 1984). For the purpose of this work, two lines of critique can be isolated within this tradition of study. The first challenges the assumption that modifications in burial practices are induced by changes in the political configuration of society. The second argues that politics provide just one of the many answers that could be given to questions of mortuary variability and ritual change.

Processual archaeologists tended to see the fossil record as directly reflecting the dynamic behaviour of people in the past. This prompted a frantic quest for ‘middle range theories’ which were thought to provide meaningful links between past and present (Binford 1977; Schiffer 1987; Trigger 2006: 414–15). In mortuary archaeology, in particular, a key component of middle range theories consisted of Saxe’s (1970) and Binford’s (1971) concept of the social persona whereby the deceased were rather mechanistically reduced to the sum of the social roles they had maintained in life. Dissatisfactions with this standpoint have been voiced by many a scholar (Barrett 1990; 1994; Hodder & Hutson 2003; Parker Pearson 1982; 1999; Thomas 1999; Ucko 1969). A common point of their critiques to the Binford-Saxe agenda is that ‘social systems are not constituted of roles but by recurrent social practices’ (Parker Pearson 1982: 100). Social theory emphasises that roles are not defined once and for all, but are continuously created and re-enacted through daily practice (Bourdieu 1977; Giddens 1984). As such, they are open to negotiation and reworking in all spheres of social life including, of course, funerals. This implies that no direct relationship can be postulated between burial and the political structure of society. Rather, both burial and politics are to be conceptualised as strategic engagements that contribute, subtly or openly, to the making and breaking of the fabric of society.

The second line of critique stresses that politics represent at best one of the possible angles for approaching the study of mortuary practices (Robb 2007b). Far from being solely concerned with status and power contests over restricted resources, funerals are increasingly understood as powerful media for social communication, which have the capability to convey several messages at once: cosmological and religious beliefs, the well-being or crisis of the social group, ideas concerning the body and personhood, and the place occupied by the dead within an idealised life-cycle (Bloch 1971; Fowler 2010; this volume; Gnoli & Vernant 1982; Goody 1962; Metcalf & Huntington 1991; Robb 2002). In particular, a fruitful strand of this research tradition claims that burial acts as a meaningful arena for defining, challenging and reworking people’s identity (Barraud et al. 1994; Brück 1995; 2001; Shanks & Tilley 1982; A. Strathern 1981; M. Strathern 1988).

Identity is an ambiguous concept that refers to the recognition of the self at both individual and group level (Diaz-Andreu & Lucy 2005; Meskell 2001). Individual identity is often conceptualised in terms of gender, age, status, and other aspects of human life which are deemed central to the self-understanding of people. However, identity is far more complex and multi-layered a concept than it might appear in the first instance. For example, it has been pointed out that each person embodies several facets of identity at the same time, each facet interacting and recombining with the others in potentially infinite ways (Meskell 2002; 2007). Moreover, Fowler (2004; 2008) drew our attention to the fact that the ideas of individual personhood and the bounded body underpinning personal identity in Western society are historically contingent. In other cultures, persons may be conceived of as partible and permeable, or as made from a combination of distinct substances, or indeed as resulting from the encounters and relationships in which one would engage in the course of their lives. This suggests caution in extending our own ideas of identity to non-Western societies.

Other aspects of identity are by definition relational. This is the case of class, caste, religion, and ethnicity. Interestingly, group identity is no less open to contrasting definitions than individual identity. In a seminal work, Jones (1997) convincingly argued that the culture-historical agenda that characterised prehistoric archaeology for the best part of the 20th century was shaped by Western ideas of ‘people’ and ‘culture’. She claimed in particular that the normative and bounded idea of the ethnic group elaborated in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries is specific to our own society, and cannot be extended uncritically to the prehistoric past. On the contrary – she argued – ethnic identity must be understood as a dynamic and contested notion, which is continually recreated and renegotiated through social practice. A similar interpretive framework has also been proposed for religion and the reworking of identity following colonial encounters (Edwards 2005; Edwards & Woolf 2004; Insoll 2007).

A common point of these investigations lies in recognising that identity cannot be understood in isolation, but only as something that is articulated through social relations. Lying at the intersection between personal ideas of the self and cultural representations of society as an orderly cosmos, identity is constantly challenged and redefined through social reproduction. Hence, it is on the dynamic interplay between individual beliefs and societal values that we must focus our attention if we are to explore how identity was conceptualised in the prehistoric past.

In this paper, I shall apply the ideas of identity hitherto discussed to investigate the profound modifications in mortuary practices, which occurred in the Italian peninsula (broadly defined as the landmass lying south of the Apennines) during the late 5th and 4th millennia BC (Fig. 2.1). I will argue, in particular, that the rise of the cemetery in this time period is not to be interpreted as a marker of major social changes, but ‘merely’ as the emergence of a new medium to express the same principles of group identity and solidarity which were previously conveyed by co-residence in nucleated villages. I will also maintain that the changing role of mortuary practices brought about, and in turn rested upon, a new understanding of the human body, which was conceived of as a more partible and permeable entity than had been previously. In turn, novel ideas of the body allowed prehistoric communities to inscribe social change into the very bones of the deceased, thus naturalising it through reference to a seemingly immutable ancestral cosmos.

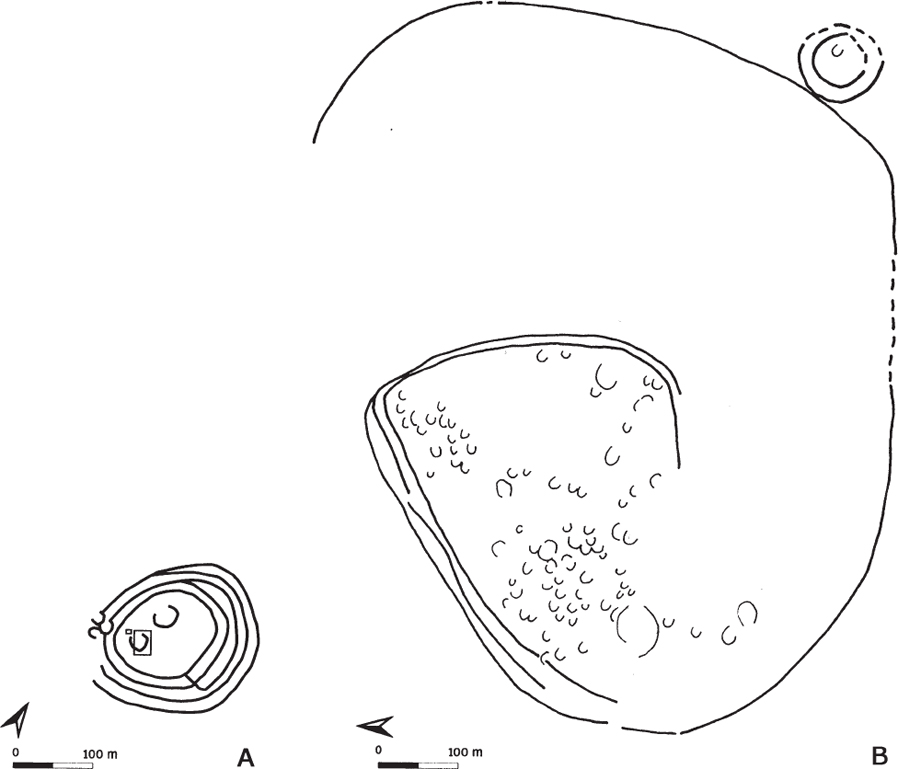

The Italian Neolithic: the age of the village

To the archaeological imagination, the Italian Neolithic is the age of the village (Robb 2007a: 76). This is best exemplified by the substantial villaggi trincerati (ditched villages) brought to light in the Apulian Tavoliere, the hinterland of Matera, and southeast Sicily since the late 19th century (Pessina & Tiné 2008). Typically measuring between 80 m and 300 m in diameter, with a few much larger, these substantial settlement sites were surrounded by series of round or elliptical ditches, which sharply divided the inner inhabited space from the outer landscape (Fig. 2.2).

At Lagnano da Piede, for example, five concentric ditches, some of which were certainly in use at the same time, encircled a 5 ha village; within it, a series of C-shaped interrupted ditches enclosed smaller areas that are normally interpreted as domestic compounds (Mallory 1984–87). At Passo di Corvo, one of the largest and best investigated villaggi trincerati in the Tavoliere, the settled area marked by the C-shaped ditches was surrounded by three large enclosures, the outer extending about 6 km out of the village to encircle what is thought to be the community’s farmland (Tiné 1983). Although ditched villages are typically found in southern Italy and Sicily, structured enclosures separating the inhabited space from the landscape are relatively common in the Italian Neolithic (Pessina & Tiné 2008: 154). For instance, traces of wooden palisades were unearthed at Pienza in the middle Tyrrhenian peninsula, and dry-stone walls encircled the inhabited area at Pulo di Molfetta and other contemporary sites in southeast Italy (Radina 2002). Similar arrangements are also known at northern Italian sites (e.g. Degasperi et al. 1998), but these lie beyond the scope of this paper.

Fig. 2.1. Map of the sites mentioned in this paper. 1: Pienza; 2: Conelle di Arcevia; 3: Ripoli; 4: Ponte San Pietro; 5: Casale del Cavaliere; 6: Maccarese; 7: Quadrato di Torre Spaccata; 8: Ortucchio; 9: Grotta dei Piccioni; 10: Cala Tramontana; 11: Passo di Corvo; 12: Pulo di Molfetta; 13: Lagnano da Piede; 14: Balsignano; 15: Cala Colombo; 16: Murgecchia; 17: Serra d’Alto; 18: Masseria Bellavista; 19: Scoglio del Tonno; 20: Arnesano; 21: Samari; 22: Serra Cicora; 23: Bronte.

Fig. 2.2. Neolithic ditched enclosures from the Apulian Tavoliere. A: Lagnano da Piede; B: Passo di Corvo (Pessina & Tiné 2008, modified).

The debate over the meaning of Neolithic enclosures has traditionally focused on the Apulian evidence, which is the most intensively researched (Brown 1991; Skeates 2002). In this region, ditches have been variously interpreted as structures built for defence (Robb 2007a: 94; Trump 1966: 42), herd containment or corralling (Jones 1987; Whitehouse 1968), the drainage and perhaps catchment of water (Bradford 1950; Gravina 1975; Tiné 1983), and the symbolic demarcation of community boundaries (Cassano & Manfredini 1983; Morter & Robb 1998). Micromorphology has revealed that water did flow in the ditches of Passo di Corvo and other Apulian sites (Pessina & Tiné 2008: 155), but it is doubtful whether water management was the intended goal of ditch building given the porosity of the base sediment, the high number of interrupted enclosures, and the frequency of villages built on relatively high ground (Manfredini 1972; Skeates 2002). It must perhaps be recognised that all interpretations have their own difficulties and limitations, and ditches may have served a plurality of functions (Robb 2007a: 94).

Whatever their practical role, it is fair to say that ditches must have provided Neolithic people with a discernible boundary between the inhabited village and the landscape (Pessina & Tiné 2008: 154; Robb 2007a: 94; Skeates 2002). Interestingly, recent research has shown that ditches were not built once and for all, but were continuously maintained through a series of practices encompassing filling as well as digging; meaningful acts of deposition including burial were also carried out at Neolithic ditches (Conati Barbaro 2007–08). It is not hard to imagine that such practices would have strongly contributed to reinforcing the common identity of the village community, and would have also helped to develop a cultural distinction between ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’. Furthermore, similar concepts of boundedness and separation can be discerned in the C-shaped ditches surrounding household compounds. These might have informed ideas of intra-kin bonds vis-à-vis the collective identity of the village population. Significantly, mortuary practices carried out in the ditches would have further contributed to defining these structures as liminal boundaries that separated not only a group from another, but also the living from the dead (Skeates 2002: 178).

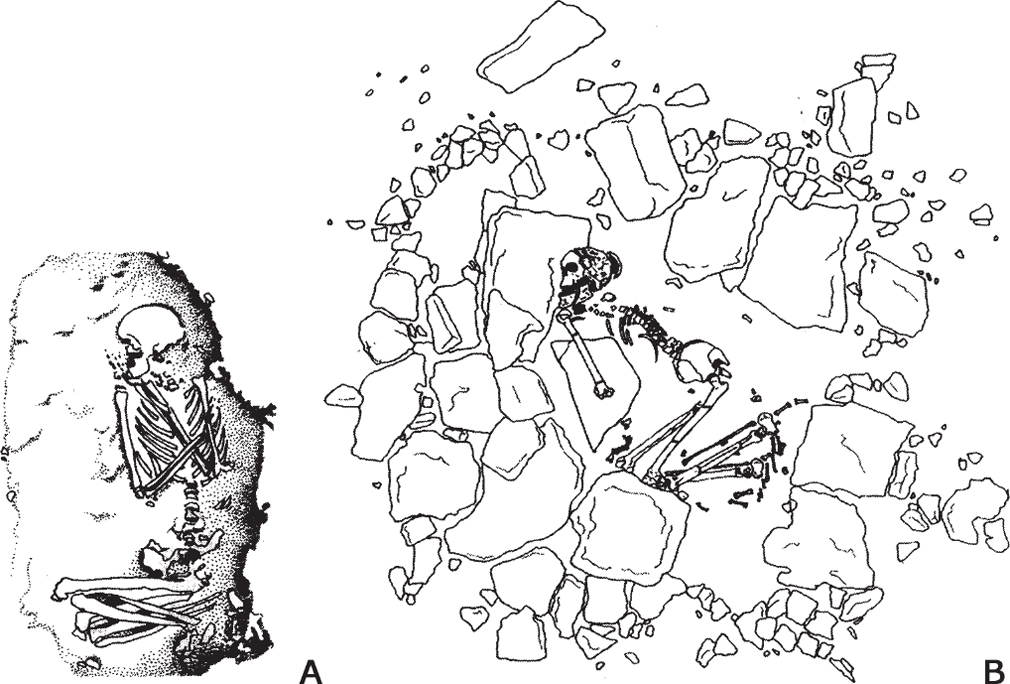

The centrality of the village for the Neolithic way of life is further emphasised by the frequent occurrence of burials (or scattered human remains) at open settlements and inhabited caves, the latter being especially common in the central Apennines (Grifoni 2003; Skeates 1997). Neolithic burial practices are extremely varied and do change remarkably in both space and time. Nonetheless, two recurrent features can be recognised in the Italian peninsular record. Firstly, for much of the Neolithic, the basic burial rite consisted of the primary inhumation of crouched individuals in earthen pits, stone-lined trenches or slab-built cists without durable goods (Fig. 2.3). Secondly, primary burial was frequently followed by the intentional or unintentional disturbance of the grave, which caused human remains to be disarticulated, fragmented, and finally dispersed within or outside the village (Pessina & Tiné 2008; Robb 2007a). The secondary treatment of bodies could take several forms ranging from the reburial of selected bones (e.g. at Samari: Cremonesi 1985–86) to their cremation (e.g. at Balsignano: Radina 2002). Acts of ancestor commemoration were also enacted at Neolithic villages. These focused on either the skull, which was sometimes removed from an otherwise complete burial (e.g. at Cala Colombo: De Lucia et al. 1977), or the undisturbed individual grave. The intentionality of the latter practice can be postulated in those cases where the undisturbed body is contained in a durable stone structure, which would have served as a visible marker for the perpetuation of ancestral memory.

Fig. 2.3. Neolithic primary burials in earthen pits and stone-lined trenches. A: Passo di Corvo; B: Balsignano, tomb 2 (Pessina & Tiné 2008, modified).

Gender is normally not stressed in the Italian Neolithic (except for a statistically significant tendency to bury males on their right-hand sides and females on their left-hand: Robb 1994a), but age occasionally is. Adult burials are slightly more numerous than children’s and were left undisturbed more frequently. Moreover, children and juveniles were usually excluded from skull curation and other acts of veneration, seemingly because their untimely death had prevented their becoming ancestral beings (Robb 2007a: 63). However, unequal preservation of children and adult bone might have concurred to creating such a scenario, and caution must be taken in interpreting data that might be distorted by a sample bias.

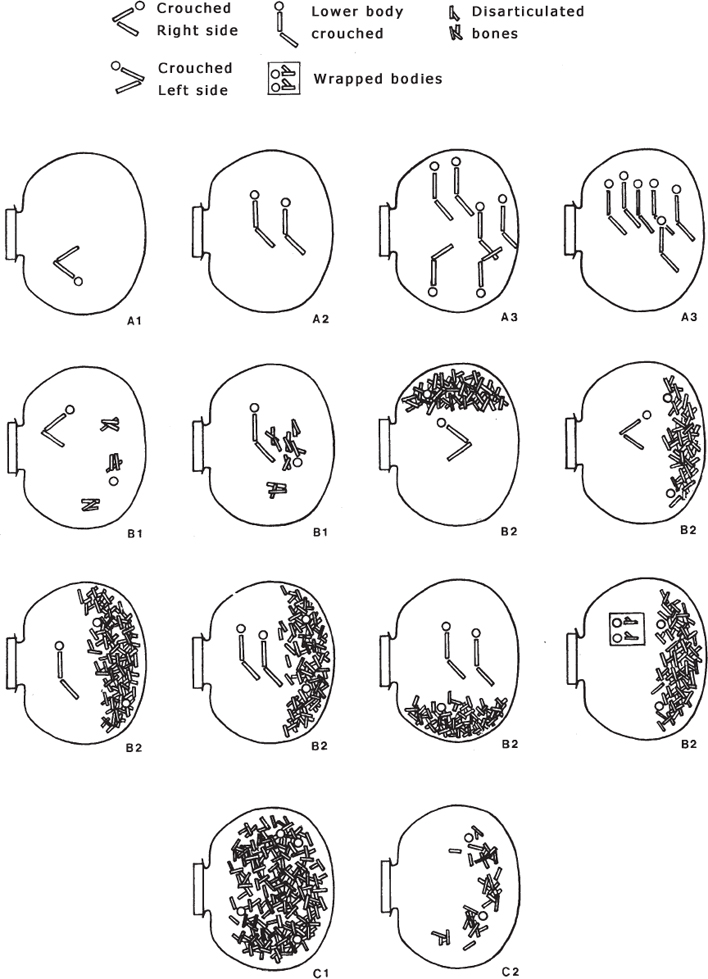

Following Gnoli and Vernant’s (1982) concept of the ‘good death’, Robb (2002) proposed interpreting the multifarious burial patterns of the Italian Neolithic according to their responding to an ideal life narrative, against which the circumstances of death would have been judged and the prescribed funerary rituals would have been performed (Fig. 2.4). Individual burial within villages or inhabited caves would have marked the normal deathway in Neolithic Italy. For most of the deceased, and with near-certainty for children and juveniles, this would have been followed by the disturbance of the grave and the dispersal of the bones, which would have marked the transformation of the dead into a non-individualised ‘ancestral presence’ for the village community. In a few cases, however, the social being of the deceased would have been preserved for remembrance and veneration by retaining their skulls or other selected remains. Finally, extraordinary circumstances of death would have compelled the performance of exceptional mortuary treatments. For example, epidemics and warfare would have dictated mass burial at special locales, and the stigmatised dead would have been left unburied. The latter practices is probably documented at Passo di Corvo, where a young woman was found lying face-down at the bottom of a well (Tiné 1983).

Fig. 2.4. Burial pathways in the early and middle Neolithic of the Italian peninsula (Robb 2002).

Two notable points emerge from Robb’s reconstruction of the Neolithic burial programme. Firstly, burial and ancestor commemoration rituals were overwhelmingly performed at villages or other inhabited sites. Ditches and houses would have provided special foci for primary and secondary burial1, although human remains are generally found wherever domestic activities were carried out, seemingly as a part of the normal detritus of daily life. Secondly, the disturbance and dispersal of human remains were probably the consequence, either wanted or unwanted, of an array of mundane tasks such as digging new pits and building new houses. However, some ancestors were singled out for individualised remembrance either by removing selected bodily remains from their graves or by consciously avoiding disturbing their tombs, for these would have been permanently inscribed in the village landscape and social fabric. It stems from both considerations that burial, both primary and secondary, was not conceptualised as qualitatively different from the rest of the day-to-day accomplishments carried out in the village, but just as one of these accomplishments – doubtless an important one. This strongly reinforces the impression that Neolithic identity and social life would have revolved around an overarching principle of co-residence within the bounded village (Robb 1994b; 2007a). Importantly, the principle was ample enough to include the newly as well as the more distant dead, whose incorporation into a village-centred cosmos would have secured the well-being and orderly reproduction of the community.

From village to cemetery: the late Neolithic and Copper Age

The picture hitherto sketched gradually changed during the late and final Neolithic (c. 4500–3600 cal. BC), when burial was increasingly performed at peripheral or otherwise distinct locales within the village as to signify separation from daily life. Moreover, mortuary rites became more complex and formalised, with special regard to secondary practices of bone manipulation and reburial. The first appearance of this long-term trend can be traced back to the late Serra d’Alto phase in the advanced middle Neolithic (Pessina & Tiné 2008: 287). In this period, small segregated burial areas were first established at sites such as Serra Cicora and Murgecchia, either at the edge of villages or, significantly, at abandoned settlement sites (Conati Barbaro 2007–08; Ingravallo 2004; Lo Porto 1998). The earliest-known cemetery proper was also founded on the outskirts of Pulo di Molfetta, a large open settlement in Apulia. Excavations carried out at this site in the early 20th century brought to light over 50 stone-lined tombs, in which a staggering variety of primary and secondary inhumation rituals had been performed, and durable goods had occasionally been placed with the dead. Interestingly, certain tombs were found devoid of any human remains. These might be interpreted as either cenotaphs or temporary repositories for burials that were later moved elsewhere (Mosso 1910; Radina 2002).

This trend gained momentum from the late 5th millennium BC. In the southern peninsula, cemeteries were established away from domestic sites at Masseria Bellavista, Scoglio del Tonno and Cala Tramontana (the latter on the Tremiti islands), and also at Bronte in Sicily (Palma di Cesnola 1967; Privitera 2012; Quagliati 1906). The high frequency of secondary burials and the growing standardisation of good assemblages witnessed at these sites openly anticipate characters that will become widespread in the Copper Age. The first hypogeal chambers reminiscent of Copper Age rock-cut tombs also appeared in the advanced 5th/early 4th millennia BC at a handful of sites including Arnesano, Serra d’Alto-Fondo Gravela and perhaps Scoglio del Tonno (Manfredini 2001; but see Pessina & Tiné 2008: 289–91 for problems of interpretation).

In the central peninsula, key evidence for this transitional phase has been yielded by the large aggregation site at Ripoli. Here, a distinct cemetery area was constructed in the unusual form of nine linear cavities cutting across the centre of the village. At least 45 individuals were buried in them, their number in each trench varying from one to 14. Skeates (1995) reconstructed a complex ritual process that would have started with the deposition of the bodies, left uncovered to decompose in the graves. Then, certain bodies would have been disarticulated and eventually all trenches would have been filled up with selected artefacts and the remains of funerary feasts. However, this reading is debated due to the scarce information available for the site, which was investigated over 100 years ago (Grifoni 2003). Caves continued to be used for burial in the late 5th and early 4th millennia BC. Even at these sites, however, interment and bone manipulation rites were progressively moved away from the cave mouths where domestic life concentrated to be increasingly performed in the deeper recesses. This pattern is particularly apparent at Grotta dei Piccioni in Abruzzo, where primary and secondary inhumation, skull deposition, and other ritual activities were all carried out at the bottom of the cave (Cremonesi 1976).

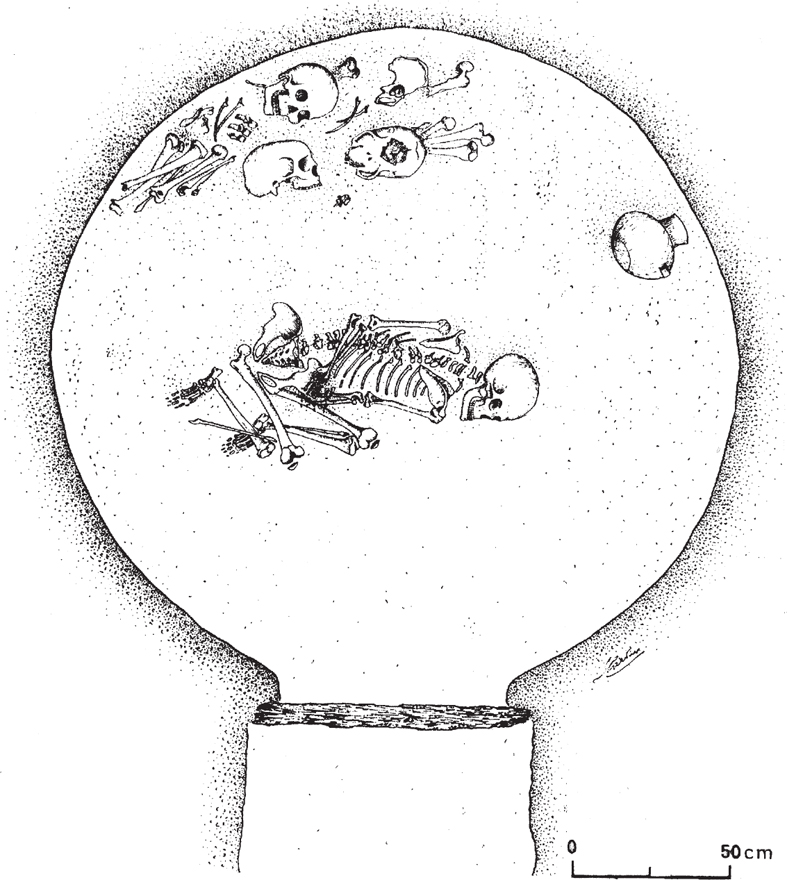

From about 3800 cal. BC, in the final Neolithic and early Copper Age, the lengthy process of separation of the dead from the living described above was brought to an end. Burial was finally moved out of domestic sites and cemeteries were created in the landscape as separate and often secluded locales for the performance of funerals and other mortuary rituals. Based on regional difference, burial was practised in rock-cut chamber tombs, uninhabited caves (or uninhabited parts of otherwise occupied caves) and, to a lesser extent, trench graves (Cocchi Genick 2009). Particularly informative in this respect is the evidence provided by the so-called Rinaldone and Gaudo funerary traditions, which were first elaborated in this time period (Cazzella & Silvestrini 2005; Passariello et al. 2010). Whereas the former is found all over central Italy with special foci in the central Tyrrhenian region and the Marche lowlands, the latter flourished in southwest Italy up to the lower Tiber valley (Carboni 2002). Both traditions are typified by small rock-cut chamber tombs preceded by entrance shafts or short corridors, and sealed by removable slabs. The new tomb structure allowed mourners to access the grave in order to carry out reburial practices and ancestor veneration rites (Fig. 2.5).

Fig. 2.5. Rinaldone-style chamber tomb from Ponte San Pietro, west-central Italy (Miari 1995).

The new mortuary programme emerging at the onset of the Copper Age was characterised by an unprecedented degree of ritual elaboration (Conti et al. 1997; Dolfini 2004). Evidence from Rinaldone-style burial chambers, albeit not uniform, suggests that the ritual process was generally divided into the following steps:

1. Interment of a fleshed and often furnished individual in crouched position, normally placed on the left-hand side regardless of their gender;

2. Manipulation of the dry bones, which were removed (partly or totally) from the grave and probably circulated within the cemetery;

3. And reburial of selected bones (usually skull and long bones), which were stacked along the tomb walls or near the entrance with the remains of other individuals (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1. The Copper Age burial programme as documented by Rinaldone-style chamber tombs, central Italy.

Interestingly, the new burial process seems to have necessitated the intermediate step to be especially elaborate. This was marked by a mind-boggling variety of bone manipulation practices ranging from the mere removal of the skull from an otherwise articulated skeleton to the complete transgression of the bodily boundaries by means of disarticulation and, more occasionally, bone fragmentation. Goods were also removed from the grave at this stage to be circulated, fragmented, and occasionally re-deposited with secondary burials.

Similar rituals were also performed in the chamber graves and entrance shafts of the Gaudo cemeteries (southwest Italy), although a greater stress was placed here on disarticulation and bone handling/circulation (Bailo Modesti 2003; Bailo Modesti & Salerno 1998). Likewise, cemeteries were divided into clusters of tombs in which descent groups would have interred their deceased and venerated their ancestors (Fig. 2.6). Such overarching similarities between Rinaldone and Gaudo burial programmes suggest that, in most of the Italian peninsula, Copper Age mortuary practices would have followed a common tripartite structure involving the interment of the fleshed body, the manipulation and circulation of the dry bones after the flesh had naturally decayed, and the final reburial of selected bones with other ancestral remains. Crucially, the fact that all stages of this process are seemingly found in the extant burial record suggests that the Copper Age mortuary programme was not intended to be linear or equifinal, for not all individuals ended up being disarticulated, and those who did were rearranged in extremely diverse manners. It would thus appear that unlike burial and manipulation practices were applied to different individuals based on their social identity and personhood as well as, presumably, the circumstances of their death. If we try to discern a meaningful pattern in the multifarious burial record of Copper Age Italy, an opposition is easily noticed between the relatively small number of individuals that were left undisturbed in the grave and the vast majority of the deceased, whose bodies were, to a smaller or greater extent, transgressed and reworked (Dolfini 2006a; 2006b). The number of possible outcomes of bodily disarticulation practices is also noteworthy, and seems to greatly exceed the spectrum of choices available to Neolithic society.

Gender and age were sometimes stressed in burial through the deposition of stereotyped sets of goods. Typically, men were disposed of with flint, groundstone or copper-alloy tools and weapons while women and children were accompanied by small ornaments including necklaces, pins, and conical V-bored buttons. To a lesser extent, gender and age were also expressed through body arrangement. In the Copper Age, however, the focus was not placed on body orientation as in the Neolithic, but on manipulation, since men were left articulated more often than women and children (Bailo Modesti & Salerno 1998: 183; Dolfini 2006a; 2006b). Moreover, whereas gender-specific goods were mostly placed with articulated burials, disarticulated and selected remains were either left unfurnished or were provided with gender-neutral goods such as copper awls and fragmented pots. This seems to suggest that gender and age, as well as presumably other elements of a person’s identity, had to be removed during the ritual process in order to integrate the new dead into a non-individualised and perhaps undifferentiated community of the ancestors (Dolfini 2004; Skeates 1995). However, in striking contrappunto to this widespread practice, the personal identity of a relatively small number of individuals, mostly adult males, was carefully preserved by leaving their bodies not only undisturbed, but also fully furnished with the complete panoply of goods with which they had been buried in the first place.

In parallel to the rise of the cemetery as a place to be exclusively devoted to the performance of mortuary rites, the long-lived nucleated village seems to disappear from the Italian landscape, or at any rate to become rarer. Substantial villages are replaced by dispersed and often short-lived settlements, isolated dwellings, and seasonally inhabited caves and open-air stations. This trend is apparent at several late Neolithic sites across the peninsula, where sizeable habitation sites give way to rather insubstantial settlements whose features often amount to a handful of pits, cobblestone floors, and hearths (Anzidei et al. 2002; Grifoni et al. 2001; Manfredini et al. 2005a; Moscoloni 1992). The trend continues well into the Copper Age at sites such as Quadrato di Torre Spaccata, Casale del Cavaliere, and Maccarese (Anzidei & Carboni 1995; Boccuccia et al. 2000; Manfredini 2002). Copper Age sites often lie close to one another on river terraces, and it is uncertain whether this should be interpreted as evidence of the same community moving to neighbouring unexploited soils or smaller groups dwelling nearby (Cazzella 1992; Gianni 1991; Moscoloni & Silvestrini 2005). In either case, however, the outcome is similar: from the late 5th millennium BC, and increasingly so during the 4th and 3rd millennia BC, communities were generally smaller and villages left fainter footprints in the landscape than they did in the early and middle Neolithic.

Fig. 2.6. Outline of Copper Age mortuary practices as documented by Gaudo-style chamber tombs, southwest Italy (Bailo Modesti & Salerno 1998, modified).

Table 2.2. Changes in settlement and burial patterns in the Neolithic and Copper Age of the Italian peninsula, c. 6th–3rd millennia BC.

|

Early and Middle Neolithic |

Late Neolithic and Copper Age |

Settlement |

Long-lived nucleated villages and (permanently?) inhabited caves |

Short-lived settlements and seasonally inhabited caves; a number of substantial settlements; aggregation sites? |

Burial place |

Within villages, especially near houses or in ditches |

In cemeteries built at the edge of villages or in extramural cemeteries |

Grave structure |

Earthen pits, stone-lined trenches and slab-built cists |

Rock-cut chamber tombs and burial caves; a number of trench graves |

Primary burial |

Inhumation of a crouched individual lying sideways |

Inhumation of a crouched individual lying sideways |

Secondary burial |

Removal of skull; intentional and unintentional bone scattering; occasional reburial of selected bones |

Great variety of manipulation and reburial practices; frequent reburial of selected bones (see Table 2.1) |

Gender and age |

Loosely defined by body orientation and burial treatment |

Strictly defined by stereotyped grave goods and, more occasionally, burial treatment |

Ancestor rituals |

Skull curation in villages; veneration of undisturbed bodies? |

Wide array of bone and artefact manipulation practices at cemeteries; veneration of undisturbed bodies? |

The demise of the nucleated village during the late Neolithic and Copper Age was long considered to be a consequence of growing seasonal mobility due to intensified pastoralism, which is especially apparent in the Apennine uplands (Barker 1981; Maggi 1998; 2002; Maggi & De Pascale 2011). Recent research has nuanced this picture by showing that lowland alluvial plains and fertile river valleys were intensively cultivated, and villages in these areas were often substantial and long-lived (Anzidei et al. 2011; Fugazzola Delpino et al. 2007; Laforgia & Boenzi 2011; Maniscalco & Robb 2011). A small number of villages were also surrounded by walls, ditches and palisades, which are normally interpreted as defence structures (Cazzella 2003b; Cazzella & Moscoloni 1999; Cerqua 2011; Cipolloni Sampò 1988; Manfredini et al. 2005b). However, notwithstanding the possibility that some communities might have continued to dwell together in large numbers during the Copper Age, some of the large upland sites including Conelle and Ortucchio might be interpreted as seasonally inhabited aggregation sites, where a dispersed population would have gathered to exchange livestock and goods, arrange marriages, and perhaps carry out youth initiation rites in which red deer and wild boar were hunted (Robb 2007a; Whitehouse 1992b). Moreover, some of the alleged defence works appear to have been maintained for very short periods of time (e.g. Cerqua 2011), thus casting doubts over their actual or intended function.

The salient features of the long-term changes outlined in this section are summarised in Table 2.2.

E pluribus, unum

The modifications in settlement and burial patterns hitherto discussed lend themselves to several possible interpretations. As we have seen above, the rise of corporate burial in the late Neolithic and Copper Age might be read as a new political strategy aiming to express ownership or inheritance claims over land and other restricted resources (Pessina & Tiné 2008; Skeates 1995). While this remains a perfectly possible scenario, it is not clear whether land was actually a rare commodity in the sparsely inhabited Neolithic and Copper Age world, perhaps with the exception of a few densely populated areas in the Adriatic lowlands. Moreover, if burial was employed as a strategy for political control, we should ask ourselves why the sourcing locales of obsidian and greenstone – some of the most prized and most widely exchanged materials in the late Neolithic world – were not protected by a ‘firewall of ancestors’, but lay apparently open for anyone to exploit.

Another long-standing tradition of studies argues that the richly furnished male burials making their appearance in the Copper Age ought to be seen as the first markers of social inequality. By displaying the prestigious tools and weapons acquired through prowess in combat and control of long-distance exchange routes, tribal leaders and ‘Big Men’ would have expressed their power according to the new ethos of the ‘prestige goods economy’ (Barker 1981; Cazzella 1992; 1998; 2003a; Guidi 2000). However, if prestige was gained through the procurement of exotic materials such as obsidian and greenstone, why did the far-reaching exchange networks of these goods flourish in egalitarian Neolithic society and crash dramatically in supposedly unequal Copper Age, where emerging tribal leaders would have needed them the most to justify power and social control? The demise of obsidian and greenstone exchange is often interpreted as the consequence of the emerging ‘trade’ in metal, which would have become the new, pervasive symbol of social prominence. Yet, failing to recognise the unlike function and social role of obsidian and copper tools in Italian prehistoric society, this reading leaves much to be desired; it also underestimates the fact that, in Copper Age Italy, metal did not circulate as extensively as obsidian and greenstone (Dolfini 2010).

I would propose here an alternative, heterodox explanation for the momentous shifts in settlement and burial patterns discussed in this paper. It is my contention that this phenomenon does not indicate any radical change in the political structure of prehistoric society. Rather, it marks a profound modification in the symbolic toolkit used by society to express individual and group identity as well as beliefs and cosmologies concerning the human body. In other words, it is not a change in the underlying ‘meaning’ of burial that we are witnessing here, but a change in the medium chosen by society to represent and reproduce itself. However, since social relations derive their meanings from the practices through which they are articulated, it would be wrong to presume that changes in the expression of burial did not cause any change in its social understanding. As we shall see in the remainder of the article, alterations to the Neolithic burial programme rested upon a wholesale re-signification of the human body, which was turned into one of the core symbolic resources deployed by society to reproduce itself.

In the early and middle Neolithic, the village acted as the principal locus for the enactment of social life. Burial was performed within the bounded village as one of the many practices, both ritual and mundane, which helped to define social relations and a sense of being in the world. When afforded archaeologically visible formal inhumation, the dead were laid, crouched and (mostly) unfurnished, in simple pits, stone-lined trenches or slab-built cists. Bodies were arranged according to loosely defined yet fairly recurrent norms dictating orientation and burial treatment, which would have responded to shared ideas concerning cosmology and identity including gender and age. Over time, most of the graves were disturbed and the dry bone dispersed, possibly during the performance of daily tasks. In a few cases, however, selected bodily remains were formally reburied, either during one-off special ceremonies or as a part of calendrical rites.

It would appear that the disturbance of the grave and the scattering of the bones responded to overarching cosmological principles dictating that all traces of the individual identity be erased during the ritual process. In this way, the individualised deceased were turned into a non-individualised ancestral presence that would have guaranteed the well-being and orderly reproduction of the village community. A principle of group solidarity and continuity was expressed through the Neolithic burial programme, in which the community took precedence over the individual (Shanks & Tilley 1982; Skeates 1995). The burying and scattering of human remains near houses, in ditches, and at other inhabited locales would have strongly contributed to the self-representation of the group as a bounded social body, and a common sense of belonging would have emerged from dwelling in a space where, from living memory, the community had interred, manipulated, and reburied its dead. Importantly, these practices were fully integrated into the daily life of the village. Burying and commemorating the dead was just one of the many tasks that were carried out at domestic sites together with the building and burning of houses, the digging and filling of ditches, the erection of palisades and so on. In Neolithic Italy, burial was not conceptualised as qualitatively different from other social practices, but just as one of the possible media – doubtless an important one – that communities had at their disposal for reproducing the core principle underpinning social life: co-residence in the bounded village.

In the late Neolithic, and increasingly so in the Copper Age, the tie between coresidence and the common history of the group split apart (Robb 1994b: 49). In most of peninsular Italy, the long-lived enclosures that had so conspicuously embodied Neolithic life disappeared from the landscape, only to be replaced by smaller and more scattered settlements, isolated houses, and seasonally inhabited caves or open-air stations. Due to their insubstantial structures, their short occupation span and, above all, their failure to accommodate the whole community within the same inhabited space, domestic sites lost their previous centrality as loci for the reproduction of group identity. Even for those communities that continued to dwell in large villages, co-residence seems to have lost its earlier importance, possibly due to an economic regime that required a higher degree of seasonal mobility. Under these circumstances, a new medium had to be found around which social relations could coalesce. Interestingly, late Neolithic society did not actually conjure the new medium out of thin air, but – as human societies habitually do – picked it from the spectrum of cultural resources that were already at hand. It is perhaps unsurprising that the choice fell on burial due to its long-standing role as a prime means for ascribing group identity and structuring social interaction. All that was required in the new circumstances was to realign the old mortuary rituals to the changing needs of increasingly mobile communities, and turn one of the many media of social reproduction into the core medium around which group identity could newly crystallise. This was a process of cultural selection, not of outright invention: E pluribus, unum.

The changing role of burial brought about a number of important modifications to the enactment and social understanding of funerary practices. The first was the invention of the cemetery, which emerged in the cultural landscape of late Neolithic Italy as the principal locus for the performance of funerals and ancestor rites. As we have seen above, this was concomitant to the slow but inexorable waning of the nucleated village as a cultural resource. It could perhaps be said that the demise of the village necessitated the cemetery to be invented insofar as smaller and more dispersed groups did require meaningful places to gather periodically in order to bury their dead, commemorate their ancestors, and ultimately reinforce the common genealogic ties that the new lifestyle had loosened. Yet such a dramatic change in the topography of burial did not rest upon a wholesale alteration in its meaning, but on an unprecedented surge in its importance as a medium for the reproduction of group identity and social relations. This is neatly indicated by the fact that the basic tenets of the Neolithic burial programme were carried through into the new era, albeit in an ‘augmented’ form. As previously, the dead were laid sideways in the grave and oriented or manipulated according to their gender, age, and presumably the circumstances of their death. As previously, the loss of individual identity through disarticulation was recognised to be the chief avenue for incorporating the new dead into the collective cosmos of the ancestors. And just as previously, ‘special’ ancestors were singled out for individual remembrance and veneration by leaving their bodies undisturbed in the grave, although the importance of this practice grew over time (Dolfini 2006a; 2006b).

The second change concerns the structure and nature of mortuary practices. Primary and secondary burial rites grew increasingly complex in the Copper Age, to a degree that has no parallels in the Neolithic world. This phenomenon can perhaps be explained by considering that, since the ancestors had become the core medium of social reproduction, a fairly simple funerary rite no longer responded to the novel needs of Copper Age communities. Genealogy had to be played up in order to tie together the threads of a common history that the new role of the village had thrown into jeopardy, and the ancestors, either real or conveniently ‘rediscovered’, were the obvious means for doing so (Robb 1994b; 2007a). In the 4th and 3rd millennia BC, people increasingly defined themselves by handling, circulating, breaking, selecting, mixing and reburying the physical bodies of their ancestors in a mind-boggling array of ritual practices. Formally, such practices would have been justified by a richer and subtler categorisation of the identity of the deceased (e.g. in terms of gender: Barfield 1998; Robb 2007a; Whitehouse 1992a; 1992b; 2001). At a deeper level, however, they were motivated by the novel desire and, indeed, social need to stress group identity and genealogic ties. In turn, the new mortuary rites required a grave structure that could periodically be accessed by the mourners: the Copper Age chamber tomb was thus born. Nevertheless, the old order was recognisably preserved within the new; for the segmentary structure of Neolithic society as expressed by the C-ditched village compounds was recreated in the cemetery in the form of separate tomb clusters where kin-groups would have buried their own dead and commemorated their own ancestors (Robb 1994b: 49).

The final and perhaps deepest change lay in the social understanding of the human body. Following Robb (2002), I have argued above that Neolithic burial was enacted according to an ideally linear programme dictating the articulated body to be disarticulated and dispersed amongst the living. However, linearity was lost in the growing complexity of Copper Age mortuary performances, as indeed was the prior (ideal) equi-finality of the burial programme. Not only were now bodies transgressed and fragmented in entirely new ways, but for the first time it was also perfectly possible to ‘interrupt’ the disarticulation process before its ‘natural’ end marked by the complete reorganisation of the body and the scattering or reburial of selected remains. Yet none of the seemingly interrupted acts of bodily manipulation found in Copper Age chamber graves is to be understood as an unfinished inhumation process. Rather, it must be recognised that all dead, be they articulated or reorganised, isolated or inextricably mixed together, selected or fragmented, underwent the ritually correct and definitive burial afforded by their personhood and identity (Dolfini 2006a: 61).

It could be suggested that, in the Italian Copper Age, the body was reconceptualised as a more partible and transgressible entity than it had been previously, and that body parts and substances would have been given specific qualities and meanings (Chapman 2000; Chapman & Gaydarska 2007; Fowler 2004; 2008; Jones 2005; Strathern 1988). Body parts could also be extracted from the dead to be employed in a range of interactions and ritual exchanges, and objects could be paired up with them, and presumably circulated with them, in mutually reinforcing signification processes (Dolfini 2004; Lucas 1996). It is not inconceivable to think that such an extensive reconfiguration of the dead might reflect broader changes in the social understanding of the living. At a time of sweeping economic and social change a mighty effort was seemingly made to represent the social body as unchanging by intensifying burial and ancestor rituals, and the tension between old and new order was thus naturalised by reference to the physical body of the dead. In this way the body, and in particular the ancestral body, became the surface on which identity, and the social relations previously expressed by the nucleated village, could newly be inscribed.

Concluding remarks

In this paper I have proposed an alternative reading for the dramatic transformations affecting prehistoric Italian society at the transition between Neolithic and Copper Age, in the late 5th and 4th millennia BC. In particular, I claimed that the momentous changes in settlement and burial patterns occurring in this time period need not indicate any radical modifications in the political structure of society. Rather, they seem to mark a profound discontinuity in the symbolic toolkit deployed by communities and kin-groups to express identity and social relations in a changing world. Since co-residence in the nucleated village could no longer be used to express a common sense of belonging and being in the world, a new medium had to be found to replace it. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the choice fell on burial, which had been employed since the early Neolithic as a prime means for structuring social interaction. Thus, I would argue, the unprecedented surge in mortuary practices witnessed at this time seems to reflect a change in the role of burial as a medium for expressing individual and group identity, not a wholesale modification in its underlying ‘meaning’.

However, the new role fulfilled by burial triggered three important changes that progressively eroded, and ultimately altered, the underlying principles of Neolithic social reproduction. The first is the invention of the cemetery, which emerged in the cultural landscape of the late Neolithic as the principal locus for funerals and ancestor rites; the second lies in the structure and nature of mortuary practices, which grew increasingly complex and elaborate in order to reinforce the genealogic ties that the new, more mobile lifestyle would have unwound; and the third is a general modification in the social configuration of the human body, which was reconceptualised as a more partible and permeable entity than it had been previously. Herein lies the most significant alteration in the meaning of mortuary practices, for new ideas of identity and personhood would have been naturalised through reference to the ancestral body. In a mighty effort to represent a fast-changing society as unchanging, prehistoric Italian communities realigned the old mortuary practices to the new social needs, and inscribed on the human body the unresolved tension between the old and the new order.

I wish to thank J. Rasmus Brandt, Marina Prusac and Håkon Roland for inviting me to the ‘Ritual Changes and Changing Rituals’ conference in Oslo, and for providing the opportunity to publish my research within this volume. I am also grateful to Chris Fowler, Alessandra Manfredini, John Robb, and an anonymous reviewer for commenting upon earlier drafts of this article, and wish to thank Giovanni Carboni and Claudio Giardino for sending relevant material. All opinions and errors are mine.

Note

1 The term ‘secondary burial’ is used in this work to signify the secondary stage of a funerary rite, which in the Italian Neolithic and Copper Age normally entailed the reorganisation, manipulation, selection, and reburial of dry bones. The term is never used here in the sense of ‘addition of burials in a context that already contains one set of remains’, as often intended in British prehistory.

Bibliography

Anzidei, A. P. & Carboni, G. 1995: ‘L’insediamento preistorico di Quadrato di Torre Spaccata (Roma) e osservazioni su alcuni aspetti tardo-neolitici ed eneolitici nell’Italia centrale’, Origini 19: 55–255.

Anzidei, A. P., Carboni, G. & Celant, A. 2002: ‘Il popolamento del territorio di Roma nel Neolitico recente/finale: aspetti culturali ed ambientali’, in Ferrari & Visentini (eds), 473–82.

Anzidei, A. P., Carboni, G., Carboni, L., Catalano, P., Celant, A., Cereghino, R., Cerilli, E., Guerrini, S., Lemorini, C., Mieli, G., Musco, S., Rambelli, C. & Pizzuti, F. 2011: ‘Il Gaudo a sud del Tevere: abitati e necropolis dell’area romana’, in Atti della XLIII Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 309–21.

Bailo Modesti, G. 2003: ‘Rituali funerari eneolitici nell’Italia peninsulare: l’Italia meridionale’, in Atti della XXXV Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, vol. I, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 283–97.

Bailo Modesti, G. & Salerno, A. 1998: Pontecagnano. La Necropoli Eneolitica: L’Età del Rame in Campania nei Villaggi dei Morti, Istituto Universitario Orientale: Naples.

Barfield, L. 1998: ‘Gender Issues in North Italian Prehistory’, in R. D. Whitehouse (ed.): Gender in Italian Archaeology: Challenging the Stereotypes, Accordia Research Institute: London, 143–56.

Barker, G. 1981: Landscape and Society: Prehistoric Central Italy, Academic Press: London.

Barraud, C., de Coppet, D., Itenau, A. & Jamous, R. 1994: Of Relations and the Dead: Four Societies viewed from the Angle of their Exchanges, Berg: Oxford.

Barrett, J. C. 1990: ‘The Monumentality of Death: The Character of Early Bronze Age Mortuary Mounds in Southern Britain, World Archaeology 22.2: 179–89.

Barrett, J. C. 1994: Fragments from Antiquity: An Archaeology of Social Life in Britain, 2900–1200 BC, Blackwell: Oxford.

Binford, L. R. 1971: ‘Mortuary Practices: Their Study and Potential’, in J. A. Brown (ed.): Approaches to the Social Dimensions of Mortuary Practices (Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology 25): 6–29.

Binford, L. R. 1977: ‘General Introduction’, in L.R. Binford (ed.): For Theory Building in Archaeology, Academic Press: New York, 1–10.

Bloch, M. 1971: Placing the Dead: Tombs, Ancestral Villages, and Kinship Organization in Madagascar, Seminar Press: London.

Boccuccia, P., Carboni, G., Gioia, P. & Remotti, E. 2000: ‘Il sito di Casale del Cavaliere (Roma) e l’Eneolitico dell’Italia centrale: problemi di inquadramento cronologico e culturale alla luce della recente datazione radiometrica’, in M. Silvestrini (ed.): Recenti acquisizioni, problemi e prospettive della ricerca sull’Eneolitico dell’Italia centrale, Regione Marche: Ancona, 231–47.

Bourdieu, P. 1977: Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Bradford, J. S. P 1950: ‘The Apulia Expedition: An Interim Report’, Antiquity 94: 84–95.

Bradley, R. 1981: ‘Various Styles of Urn: Cemeteries and Settlement in Southern England c. 1400–1000 BC’, in Chapman et al. (eds): 93–104.

Brown, K. 1991. ‘A Passion for Excavation: Labour Requirements and Possible Functions for the Ditches of the “villaggi trincerati” of the Tavoliere, Apulia’, Accordia Research Papers 2: 5–30.

Brück, J. 1995: ‘A Place for the Dead: The Role of Human Remains in the Late Bronze Age’, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 61: 245–77.

Brück, J. 2001: ‘Body Metaphors and Technologies of Transformation in the English Middle and Late Bronze Age’, in J. Brück (ed.): Bronze Age Landscapes: Tradition and Transformation, Oxbow Books: Oxford, 149–60.

Carboni, G. 2002: ‘Territorio aperto o di frontiera? Nuove prospettive di ricerca per lo studio della distribuzione spaziale delle facies del Gaudo e di Rinaldone nel Lazio centro-meridionale’, Origini 24: 235–301.

Cassano, S. M. & Manfredini, A. (eds) 1983: Studi sul Neolitico del Tavoliere della Puglia: indagine territoriale in un’area-campione, British Archaeological Reports, International Series 160: Oxford.

Cazzella, A. 1992: ‘Sviluppi culturali eneolitici nella penisola italiana’, in Cazzella, A. & Moscoloni, M. (eds): Neolitico ed Eneolitico (Popoli e Civiltà dell’Italia Antica 11), Biblioteca di storia patria: Rome, 349–643.

Cazzella, A. 1998: ‘Modelli e variabilità negli usi funerari di alcuni contesti eneolitici italiani’, Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche 49: 431–45.

Cazzella, A. 2003a: ‘Rituali funerari eneolitici nell’Italia peninsulare: l’Italia centrale’, in Atti della XXXV Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, vol. I, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 275–82.

Cazzella, A. 2003b: ‘Aspetti e problemi dell’Eneolitico in Abruzzo’, in Atti della XXXVI Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 221–38.

Cazzella, A. & Moscoloni, M. 1999: Conelle di Arcevia: un insediamento eneolitico nelle Marche, Gangemi: Rome.

Cazzella, A. & Silvestrini, M. 2005: ‘L’Eneolitico delle Marche nel contesto degli sviluppi culturali dell’Italia centrale’, in Atti della XXXVIII Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, vol. I, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 371–86.

Cerqua, M. 2011: ‘Selva dei Muli (Frosinone): un insediamento eneolitico della facies del Gaudo’, Origini 33: 157–248.

Chapman, J. 2000: Fragmentation in Archaeology: People, Places and Broken Objects in the Prehistory of the South-Eastern Europe, Routledge: London.

Chapman, J. & Gaydarska, B. 2007: Parts and Wholes: Fragmentation in Prehistoric Context, Oxbow Books: Oxford.

Chapman, R., Kinnes, I. & Randsborg, K. (eds) 1981: The Archaeology of Death, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Cipolloni Sampò, M. 1988: ‘La fortificazione eneolitica di Toppo Daguzzo (Basilicata)’, Rassegna di Archeologia 7: 557–58.

Cocchi Genick, D. 2009: Preistoria, QuiEdit: Verona.

Conati Barbaro, C. 2007–08: ‘Custodire la memoria: le sepolture in abitato nel Neolitico italiano’, Scienze dell’Antichità 14(1): 49–70.

Conti, A. M., Persiani, C. & Petitti, P. 1997: ‘I riti della morte nella necropoli eneolitica della Selvicciola (Ischia di Castro – Viterbo)’, Origini 21: 169–85.

Cremonesi, G. 1976: La Grotta dei Piccioni di Bolognano nel quadro delle culture dal Neolitico all’Età del Bronzo in Abruzzo, Giardini: Pisa.

Cremonesi, G. 1985–86: ‘Samari (Gallipoli)’, Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche 40: 424–25.

Degasperi, N., Ferrari, A. & Steffè, G. 1998: ‘L’insediamento neolitico di Lugo di Romagna’, in Pessina & Muscio (eds): 117–24.

De Lucia, A., Ferri, D., Geniola, A., Giove, C., Maggiore, M., Melone, N., Pesce Delfino, V., Pieri, V. & Scattarella, V. 1977: La comunità Neolitica di Cala Colombo presso Torre a Mare, Bari, Società per lo Studio di Storia Patria per la Puglia: Bari.

Diaz-Andreu, M. & Lucy, S. 2005: ‘Introduction’, in Diaz-Andreu et al. (eds): 1–12.

Diaz-Andreu, M., Lucy, S., Babić, S. & Edwards, D. N. (eds.) 2005: The Archaeology of Identity, Routledge: London.

Dolfini, A. 2004: ‘La necropoli di Rinaldone (Montefiascone, Viterbo): rituale funerario e dinamiche sociali di una comunità eneolitica in Italia centrale’, Bullettino di Paletnologia Italiana 95: 127–278.

Dolfini, A. 2006a: ‘Embodied Inequalities: Burial and Social Differentiation in Copper Age Central Italy’, Archaeological Review from Cambridge 21.2: 58–77.

Dolfini, A. 2006b: ‘L’inumazione primaria come sistema simbolico e pratica sociale’, in N. Negroni Catacchio (ed.), Preistoria e Protostoria in Etruria: Atti del VII Incontro di Studi, II, Centro Studi di Preistoria e Archeologia: Milan, 461–72.

Dolfini, A. 2010: ‘Metalwork Exchange in Chalcolithic Italy: Fact or Fiction?’, Paper presented at the 16th Annual Meeting of the European Association of Archaeologists (Den Haag 2010).

Edwards, D. N. 2005: ‘The Archaeology of Religion’, in Diaz-Andreu et al. (eds): 110–28.

Edwards, C. & Woolf, G. 2004: ‘Cosmopolis: Rome as World City’, in C. Edwards & D. Edwards (eds): Rome the Cosmopolis, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1–20.

Ferrari, A. & Visentini, P. (eds) 2002: Il declino del mondo neolitico, Comune di Pordenone: Pordenone.

Fowler, C. 2004: The Archaeology of Personhood: An Anthropological Approach, Routledge: London.

Fowler, C. 2008: ‘Fractal Bodies in the Past and Present’, in D. Borić & J. Robb (eds): Past Bodies: Body-Centred Research in Archaeology, Oxbow Books: Oxford, 47–57.

Fowler, C. 2010: ‘Pattern and Diversity in the Early Neolithic Mortuary Practices of Britain and Ireland: Contextualising the Treatment of the Dead’, Documenta Praehistorica 37: 1–22.

Fugazzola Delpino, M. A., Salerno, A. & Tinè, V. 2007: ‘Villaggi e necropoli dell’area “Centro Commerciale” di Gricignano d’Aversa – US Navy (Caserta)’, in Atti della XL Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Presitoria e Protostoria, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 521–37.

Gianni, A. 1991: ‘Il farro, il cervo ed il villaggio mobile’, Scienze dell’Antichità 5: 99–161.

Giardino, C., Guida, G. & Occhini, G. 2011: ‘La prima metallurgia dell’Italia centrale tirrenica e lo sviluppo tecnologico della facies di Rinaldone: evidenze archeologiche e sperimentazione’, in Atti della XLIII Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Presitoria e Protostoria, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 181–86.

Giddens, A. 1984: The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration, University of California Press: Berkeley.

Gnoli, G. & Vernant, J.-P. 1982: La mort, les morts dans les sociétés anciennes, Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme: Paris.

Goody, J. 1962: Death, Property and the Ancestors: A Study of the Mortuary Customs of the Lo Dagaa of West Africa, Tavistock: London.

Gravina, A. 1975: ‘Fossati e strutture ipogeiche dei villaggi neolitici in agro di S. Severo’, Attualità Archeologiche 1: 14–34.

Grifoni, R. 2003: ‘Sepolture neolitiche dell’Italia centro-meridionale e loro relazione con gli abitati’, in Atti della XXXV Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, vol. I, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 259–74.

Grifoni, R., Radi, G. & Sarti, L. 2001: ‘Il Neolitico della Toscana’, in Atti della XXXIV Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 57–70.

Guidi, A. 2000: Preistoria della complessità sociale, Laterza: Roma.

Hodder, I. & Hutson, S. 2003: Reading the Past: Current Approaches to Interpretation in Archaeology, 3rd edition, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Hodder, I. (ed.) 1982: Symbolic and Structural Archaeology, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

Ingravallo, E. 2004: ‘Il sito Neolitico di Serra Cicora (Nardò, Lecce): note preliminari’, Origini 26: 87–119.

Insoll, T. 2007: ‘Introduction: Configuring Identities in Archaeology’, in Insoll (ed.): 1–22.

Insoll, T. (ed.) 2007: The Archaeology of Identities: A Reader, Routledge: London.

Jones, A. 2005: ‘Lives in Fragments? Personhood and the European Neolithic’, Journal of Social Archaeology 5: 193–224.

Jones, G. D. B. 1987: Apulia I: Neolithic Settlement in the Tavoliere, Society of Antiquaries: London.

Jones, S. 1997: The Archaeology of Ethnicity, Routledge: London.

Laforgia, E. & Boenzi, G. 2011: ‘Nuovi dati sull’Eneolitico della piana campana dagli scavi A.V. in provincia di Napoli’, in Atti della XLIII Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Presitoria e Protostoria, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 249–55.

Lo Porto, F. G. 1998: Murgia Timone e Murgecchia (Monumenti Antichi dei Lincei 30), Accademia dei Lincei: Rome.

Lucas, G. 1996: ‘Of Death and Debt: A History of the Body in Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Yorkshire’, Journal of European Archaeology 4: 99–118.

Maggi, R. 1998: ‘Storia della Liguria fra 3600 e 2300 avanti Cristo (età del Rame)’, in A. Del Lucchese & R. Maggi (eds): Dal diaspro al bronzo, Luna: La Spezia, 7–28.

Maggi, R. 2002: ‘Pastori, miniere, metallurgia nella transizione fra Neolitico ed età del Rame: nuovi dati dalla Liguria’, in Ferrari & Visentini (eds): 437–40.

Maggi, R. & De Pascale, A. 2011: ‘Fire making Water on the Ligurian Apennines’, in M. Van Leusen, G. Pizziolo & L. Sarti (eds): Hidden Landscapes of Mediterranean Europe, British Archaeological Reports, International Series 2320: Oxford, 105–12.

Mallory, J. P. 1984–87: ‘Lagnano da Piede I: An Early Neolithic Village in the Tavoliere, Origini 13: 193–290.

Manfredini, A. 1972: ‘Il villaggio trincerato di Monte Aquilone nel quadro del neolitico dell’Italia meridionale’, Origini 6: 29–154.

Manfredini, A. 2001: ‘Rituali funerari e organizzazione sociale: una rilettura di alcuni dati della facies Diana in Italia meridionale’, in M. C. Martinelli & U. Spigo (eds): Studi di Preistoria e Protostoria in onore di Luigi Bernabò Brea, Museo Archeologico Regionale Eoliano: Lipari, 71–87.

Manfredini, A. (ed.) 2002: Le dune, il lago, il mare: Una comunità di villaggio dell’età del Rame a Maccarese, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence.

Manfredini, A., Sarti, L. & Silvestrini, M. 2005a: ‘Il Neolitico delle Marche’, in Atti della XXXVIII Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, vol. I, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 197–208.

Manfredini, A., Carboni, G., Conati Barbaro, C., Silvestrini, M., Fiorentino, G. & Corridi, C. 2005b: ‘La frequentazione eneolitica di Maddalena di Muccia (Macerata)’, in Atti della XXXVIII Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, vol. II, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 433–44.

Maniscalco, L. & Robb, J. 2011: ‘L’organizzazione dello spazio durante l’età del rame in Italia meridionale, Sicilia e Malta’, in Atti della XLIII Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Presitoria e Protostoria, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 279–85.

Meskell, L. 2001: ‘Archaeologies of Identity’, in Hodder, I. (ed.): Archaeological Theory Today, Polity Press: Cambridge, 187–213.

Meskell, L. 2002: ‘The Intersections of Identity and Politics in Archaeology’, Annual Review of Anthropology 31: 279–301.

Meskell, L. 2007: ‘Archaeologies of Identity’, in Insoll (ed.): 23–43.

Metcalf, P. & Huntington, R. 1991: Celebrations of Death, 2nd edition, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Miari, M. 1995: ‘Il rituale funerario della necropoli eneolitica di Ponte S. Pietro (Ischia di Castro, Viterbo)’, Origini 18: 351–90.

Morter, J. & Robb, J. 1998: ‘Space, Gender and Architecture in the Southern Italian Neolithic’, in R. D. Whitehouse (ed.): Gender in Italian Archaeology: Challenging the Stereotypes, Accordia Research Institute: London, 83–94.

Moscoloni, M. 1992: ‘Sviluppi culturali neolitici nella penisola italiana’, in A. Cazzella & M. Moscoloni (eds): Neolitico ed Eneolitico (Popoli e Civiltà dell’Italia Antica 11), Biblioteca di Storia Patria: Rome, 9–348.

Moscoloni, M. & Silvestrini, M. 2005: ‘Gli insediamenti eneolitici delle Marche’, in Atti della XXXVIII Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, vol. I, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 421–31.

Mosso, A. 1910: ‘La necropoli neolitica di Molfetta’, Monumenti Antichi dei Lincei 20: 237–356.

O’Shea, J. 1981: ‘Social Configurations and the Archaeological Study of Mortuary Practices: A Case Study’, in Chapman et al. (eds): 39–52.

Palma di Cesnola, A. 1967: ‘Il neolitico medio e superiore di San Domino (Arcipelago delle Tremiti)’, Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche 22: 349–91.

Parker Pearson, M. 1982: ‘Mortuary Practices, Society and Ideology: An Ethnoarchaeological Study’, in Hodder (ed.): 99–114.

Parker Pearson, M. 1999: The Archaeology of Death and Burial, Sutton: Phoenix Mill.

Passariello, I., Talamo, P., D’Onofrio, A., Barta, P., Lubritto, C. & Terrasi, F. 2010: ‘Contribution of Radiocarbon Dating to the Chronology of Eneolithic in Campania (Italy)’, Geochronometria 35: 25–33.

Peroni, R. 1989: Protostoria dell’Italia continentale: la penisola italiana nelle età del Bronzo e del Ferro (Popoli e Civiltà dell’Italia Antica 9), Biblioteca di storia patria: Rome.

Peroni, R. 1996: L’Italia alle soglie della Storia, Laterza: Rome.

Pessina, A. & Muscio, G. (eds) 1998: Settemila anni fa… il primo pane: ambienti e culture delle società neolitiche, Museo Friulano di Storia Naturale: Udine.

Pessina, A. & Tiné, V. 2008: Archeologia del Neolitico. L’Italia tra VI e IV millennio a.C., Carocci: Rome.

Privitera, F. 2012: ‘Necropoli tardo-neolitica in contrada Balze Soprana di Bronte’, in Atti della XLI Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Florence, 543–56.

Quagliati, Q. 1906: ‘Tombe neolitiche in Taranto e nel suo territorio’, Bullettino di Paletnologia Italiana 30: 17–49.

Radina, F. (ed.) 2002: La Preistoria della Puglia. Paesaggi, uomini e tradizioni di 8000 anni fa, Adda: Bari.

Robb, J. E. 1994a: ‘The Neolithic of Peninsular Italy: Anthropological Synthesis and Critique’, Bullettino di Paletnologia Italiana 85: 189–214.

Robb, J. E. 1994b: ‘Burial and Social Reproduction in the Peninsular Italian Neolithic’, Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 7.1: 27–71.

Robb, J. E. 2002: ‘Time and Biography: Osteobiography of the Italian Neolithic Lifespan’, in Y. Hamilakis, M. Pluciennik & S. Tarlow (eds): Thinking Through the Body: Archaeologies of Corporeality, Kluwer Academic/Plenum: London, 153–71.

Robb, J. E. 2007a: The Early Mediterranean Village: Agency, Material Culture, and Social Change in Neolithic Italy, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Robb, J. E. 2007b: ‘Burial Treatment as Transformations of Bodily Ideology’, in N. Laneri (ed.): Performing Death, The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: Chicago, 287–97.

Saxe, A. 1970: Social Dimension of Mortuary Practices, Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor.

Schiffer, M. B. 1987: Formation Processes of the Archaeological Record, University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque.

Shanks, M. & Tilley, C. 1982: ‘Ideology, Symbolic Power and Ritual Communication: A Reinterpretation of Neolithic Mortuary Practices’, in Hodder (ed.): 129–54.

Skeates, R. 1995: ‘Transformations in Mortuary Practice and Meaning in the Neolithic and Copper Age of Lowland East-Central Italy’, in W. H. Waldren, J. A. Ensenyat & R. C. Kennard (eds): Ritual, Rites and Religion in Prehistory, British Archaeological Reports, International Series 611: Oxford, 211–37.

Skeates, R. 1997: ‘The Human Use of Caves in East-Central Italy during the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Copper Age’, in C. Bonsall & C. Tolan–Smith (eds): The Human Use of Caves, British Archaeological Reports, International Series 667: Oxford, 79–86.

Skeates, R. 2002. ‘The Social Dynamics of Enclosure in the Neolithic of the Tavoliere, Southeast Italy, Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 13.2: 155–88.

Strathern, A. 1981: ‘Death as Exchange: Two Melanesian Cases’, in S. Humphries & H. King (eds): Mortality and Immortality: The Archaeology and Anthropology of Death, Academic Press: London, 205–23.

Strathern, M. 1988: The Gender of the Gift, University of California Press: Berkeley.

Tainter, J.A. 1978: ‘Mortuary Practices and the Study of Prehistoric Social Systems’, in M. Schiffer (ed.): Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 1: 105–41.

Thomas, J. 1999: Understanding the Neolithic, Routledge: London.

Tiné, S. 1983: Passo di Corvo e la Civiltà Neolitica del Tavoliere, Sagep: Genoa.

Trigger, B. G. 2006: A History of Archaeological Thought, 2nd edition, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Trump, D. H. 1966: Central and Southern Italy before Rome, Thames and Hudson: London.

Ucko, P. J. 1969: ‘Ethnography and Archaeological Interpretation of Funerary Remains’, World Archaeology 1(2): 262–80.

Whitehouse, R. D. 1968: ‘Settlement and Economy in Southern Italy in the Neothermal Period’, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 34: 332–66.

Whitehouse, R. D. 1992a: ‘Tools the Manmaker: The Cultural Construction of Gender in Italian Prehistory’, Accordia Research Papers 3: 41–53.

Whitehouse, R. D. 1992b: Underground Religion: Cult and Culture in Prehistoric Italy, Accordia Research Institute: London.

Whitehouse, R. D. 2001: ‘Exploring Gender in Prehistoric Italy’, Papers of the British School at Rome 68: 49–96.