SALLY YOUNG

IN JUNE 1880, one of the biggest news stories in Australian history broke at Glenrowan, Victoria. After years of eluding the police, Ned Kelly and his gang staged a final confrontation at the Glenrowan Inn. Kelly was shot and arrested, while the other members of his gang were shot dead by police or died in the fire that burnt through the hotel after police tried to smoke them out. Sepia photographs of the bodies and burnt-out hotel were taken by several photographers, including JW Lindt, Oswald Thomas Madeley and John Bray. But none of these photographers were newspaper staff—they were a mix of studio, amateur and freelance photographers, some commissioned by the police. While the capture of the Kelly gang was a momentous story for newspapers, no photographs were included in their dramatic reports because it was still technically too difficult for a newspaper to print a photograph onto a newspaper page.

The only newspapers to record the event visually were illustrated newspapers, which relied upon engravers and woodblock illustration. While one ‘enterprising Melbourne newspaper’ employed commercial photographer Lindt to take photographs, these were only used as a guide for the paper’s woodcut artists.1 A sketch artist also rushed in person to Glenrowan to record the event for an illustrated newspaper, and he is visible in one of Lindt’s photographs of the body of Kelly gang member Joe Byrne. In the foreground at left, wearing a bowler hat, is the English artist Julian Ashton, who worked for David Syme’s Illustrated Australian News.2 Ashton can be seen with his sketchbook tucked under his arm, having just completed a sketch while sitting on the cold cement floor of a police cell using the light of a candle. Afterwards, the photographers persuaded the police to hang Byrne’s body on a pulley outside so they could photograph it.3 It took four days for Ashton’s sketch to be published, in the 3 July edition of Illustrated Australian News, while woodblock illustrations based on photographs of the hanging body appeared in several newspapers and journals, including the Bulletin, on 10 July.4

1.1 Joe Byrne’s body outside Benalla Police Station, sepia photograph by JW Lindt, 29 June 1880 (State Library Victoria Pictures Collection).

Eight years later, newspapers were in a much better position to include photographs after the development of the half-tone technique. Half-tone allowed engravers to incorporate a photograph into the rest of the text by setting and reproducing it on the same printing plate in a format that used different sized dots. This was a new and expensive process and the results were not always good. Nonetheless, as historian Kate Evans notes, it was a ‘great revolution in newspaper illustrating’ because, previously, newspapers had only been able to ‘tip in’ individual photographic pages ‘as exotic or artistic pages on separate glossy paper’. The new technique, Evans argues, ‘changed the relationship of the photograph to written text, and absorbed it into the everyday material of the paper’.5 It also, as veteran photographer Bruce Howard explains, heralded the birth of two new groups of workers within the newspaper industry: the photoengraving process department and press photographers.6

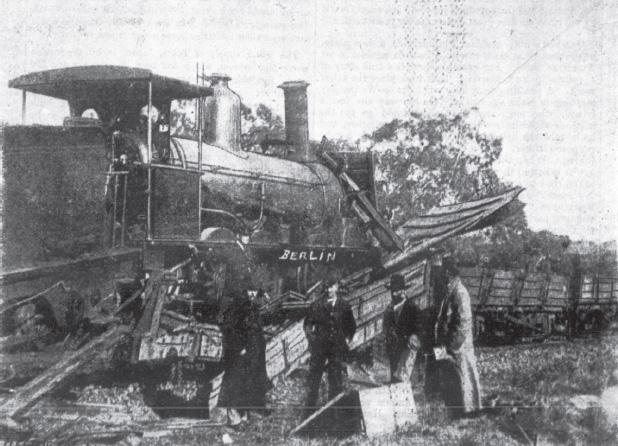

Using the new method, a photograph of a railway accident at Young, New South Wales, was published in 1888 by John Fairfax & Sons’ weekly newspaper the Sydney Mail. This has been widely claimed to be the first photograph to appear in an Australian newspaper.7 The photograph was taken by George Berlin, a travelling commercial photographer. Berlin had a distinctive way of ensuring he was given credit for the photograph—he painted his name on the steam engine of the train! This desire for attribution and recognition was an issue for photographers for the next hundred years as they were not routinely given by-line credits for their photographs until the 1980s.

Despite its advantages, the half-tone process was expensive and cumbersome for daily press deadlines. More than a decade after it was introduced, most papers still only published photographs occasionally, but continued using them as a basis for drawings that appeared in the paper.8 Mass-circulation newspapers used rotary presses, which, at first, were not as effective at printing half-tone as the offset printers used by the major illustrated magazines. This was also a discouraging factor.9

That photographs were not immediately taken up with enthusiasm was not only about practical, technical or economic factors. It was also about attitudes towards images. Although the Sydney Mail had begun as a weekly review edition of the Sydney Morning Herald for country readers, it had developed into a high-quality magazine with a reputation for its illustrations. By 1888, it had a seventeen-year tradition of using illustrations, but when it published the train accident photograph, it placed it in an incongruous manner, out of context and eleven pages away from the news story of the event, demonstrating an initial uncertainty about how to use ‘real pictures’ to illustrate news.

1.2 Railway accident at Young, photograph by George Berlin, 15 September 1888. The Sydney Mail, page 558 (National Library of Australia).

The papers ‘of record’, the broadsheet newspapers, were not merely unsure about photography but resistant. Evans documents how broadsheets ‘defined themselves against’ the populist appeal of photographs, associating them with ‘low-brow’, emotional news coverage.10 The Sydney Mail’s parent newspaper, the SMH, did not publish a photograph until twenty years after the Sydney Mail, replicating a trend also apparent in the United States in this era, whereby daily newspapers used a weekly magazine-type supplement to exploit the growing popularity of photography while insulating their primary product ‘from being downgraded by the photograph’.11

By contrast, the enthusiasm of the illustrated and tabloid-style press was reflected in their employment of the first press photographers. James HF Eastman began working with the Argus’s illustrated weekly magazine, the Australasian, in 1895 and spent more than forty years as a press photographer with the Australasian/Argus before he died while taking photographs at the Ford factory in 1934.12 The Herald and Weekly Times (HWT) appears to be the first Australian newspaper company to employ a full-time photographer, Edgar Sutcliff, in 1899.13 Around the same time, George Bell was hired as one of the Sydney Mail’s first generation of in-house photojournalists. The Sydney Mail then established its own in-house photographic department in 1902.14 Like many of the early press photographers, Bell had been a studio photographer, travelling the country on horseback taking stylised photographs using glass-plate negatives.15 He worked for the Sydney Mail (SMH) for nearly forty years. When the then Duke of York (later George V) made a royal tour of Australia in 1901, Eastman and Bell made a pictorial record of the tour for their papers.

The SMH published its first photograph in 1908, stirred by the great public excitement caused by the US Fleet’s visit to Australia. The SMH published its photograph on page two, showing the US Navy’s ‘Great White Fleet’ steaming into Sydney Harbour.16 Earlier that year, on 22 April 1908, the Age had published its first photograph—also of a train accident. Train accidents were a visual spectacle and newsworthy, because trains were the key mode of mass transport and supply, but there was also a practical appeal—train wreckage was not easy to move so stayed in place long enough for a photographer to get to the scene and take a photograph.

The Age made special mention of its first photograph, captioning it as ‘taken specially for the Age’. The commercial value of photographs that bore witness to a news event and were exclusive to a newspaper was increasingly recognised at a time when newspaper competition was robust. In 1903, there were twenty capital-city daily newspapers in Australia, owned by seventeen different owners. By 1919, this had risen to twenty-four daily newspapers.17 By 1912, both the Telegraph and the Sun in Sydney were employing photographers.18 Journalists also began to write about, and draw public attention to, the daring feats of photographers such as ‘Cheeky’ Jack Turner of the Sydney Sun, who took an extraordinary aerial photograph of the warship HMAS Melbourne in 1913 by climbing up the main mast and hanging on with one leg and one arm while focusing his large, heavy camera.19

Newspaper audiences were especially hungry for information during World War I, and broadsheets and tabloids began to publish pictures far more regularly during this period.20 While ambivalence towards photography was diminishing, it took time and stylistic innovations in newspaper design before photographs began to be seen as more than just an adjunct illustration and began to obtain a special status as an independent form of evidence associated with scientific—and journalistic—objectivity.21

Newspapers and other forms of printed material became increasingly visual during the 1920s, a period the pioneering media scholar Henry Mayer calls ‘by far the toughest and most ruthless period in Australian journalism’.22 In 1923, twenty-six capital-city daily newspapers, owned by twenty-one different owners, competed for news audiences.23 Improving technology in cameras allowed for a wider range of events to be photographed. Larger, more sensational photographs began to appear in the tabloid-style press on themes such as violence, crime, accidents and society scandals. Herbert Fishwick at the Sydney Mail and SMH had a special 40-inch telephoto lens made for his Graflex camera, especially for taking cricket photographs. This caused a sensation when the images were shown in England and heralded the birth of long-lens photography.24 The photographer’s place in newspapers became more assured,25 and the Australian Journalists Association (AJA) union accepted staff and freelance photographers as members.26 The SMH employed its own photographers in 1925, and the Age in 1927, when it hired Hugh Bull as its first full-time photographer. This was nearly three decades after rival HWT’s first full-time appointment. Bull’s camera weighed 20 kilograms.27 Bull’s appointment was the beginning of a press photography dynasty, with three of his sons and two of his grandsons also becoming press photographers.28

The growing significance of the image was cemented on 11 September 1922 with the first edition of the first pictorial daily newspaper in Australia. The Sun News-Pictorial (Melbourne) was the brainchild of Monty Grover, modelled on the London Mirror and Sketch.29 Its pictures-only front page continued into the 1930s.30 The front page of the first edition presents a tabloid formula of sport, crime, royalty, entertainment, celebrity, accidents and cute animals that would not be out of place today. It includes photographs of horseracing, the Prince of Wales, society belle Lady Loughborough, a car accident involving a ‘lady driver’, a cat (who had taken up residence at the Sun’s new office) and a policeman directing traffic. Inside the paper, more photographs of horseracing were accompanied by photographs of football, hockey, baseball, actors and a crime scene involving the ransacking of a bookmaker’s house. But the ‘file-footage’ photograph of the Prince of Wales in Cornwall, along with photographs seemingly taken out of convenience—such as the office cat—suggests that good images were scarce. The Sun openly stated that it needed more photographs in an ad on the back page, saying it would pay for news photos from ‘either amateur or professional photographers’.

1.3 The first pictorial daily in Australia. The Sun News-Pictorial, 11 September 1922 (News Corporation Australia/State Library of NSW).

By the 1930s, small photographs appeared more frequently on inside news pages, and photography had become more central to newspaper routines. The SMH now had ‘half a dozen or more’ photographers on staff.31 The Herald and Sun News-Pictorial photographers experimented with taking high-speed photographs at night and applied for a patent for their process. Photographs were increasingly seen as a lure for audiences, and many newspapers attempted to imitate the immensely popular Sun News-Pictorial with its bold use of headlines and photographs, a visual style encouraged by Keith Murdoch through his employment of staff photographers after the Herald bought the Sun News-Pictorial in April 1925.

In Sydney, when Robert Clyde Packer took charge in September 1931 as managing editor of the Sun, Sunday Sun, Daily Telegraph and Sunday Guardian, those newspapers also quickly increased their ratio of photographs to text.32 Packer had already had some success in the 1920s by imitating US tabloids and pioneering the ‘Miss Australia’ quest, asking women to send in full-length photographs of themselves in swimsuits, which were published in both the Guardian and Smith’s Weekly.33 The Australian Women’s Weekly, introduced in 1933 by his son Frank Packer, was also extremely influential, not only upon newspapers and news audiences, but also upon the careers of many press photographers who worked for the Packer family’s newspapers.

News photography became integral after the outbreak of World War II in 1939. Twenty-seven professional photographers and eighty-eight enlisted soldiers were accredited as Australian war photographers over the duration of the war. Reflecting both newsprint supply rationing and the shift to a more pictorial-news format, a number of newspapers changed to tabloid size. The tabloid Daily Mirror began in 1941, while the Argus, the Daily Telegraph, the Brisbane Telegraph and the West Australian all converted from broadsheet to tabloid size in the 1940s. Conservative broadsheets also modernised their news presentation. In April 1944, the SMH changed to printing news on its front page rather than advertising, one of the last metropolitan newspapers to make that shift. The SMH also published its first front-page photograph that year, taken by Harry Martin.34 Newsprint restrictions challenged the newspapers’ capacity to print large editions, and camera film was also in short supply during the war. But there was nonetheless a growing sense of the role of photography in news, and in drawing attention to social issues. Outside of newspapers, there was an increasing acceptance of photographers as artists, with photographers such as Harold Cazneaux, Max Dupain and, later, David Moore inspiring greater quality. Within newspapers, the visual was increasingly prominent, with illustrations and cartoons also blooming during this period.35

By the 1950s, cameras were lighter and had new types of shutters and electronic flashes. Press photography was now, as Evans notes, ‘vibrant, and influential’.36 On 28 July 1952, the Argus became the first newspaper anywhere in the world to produce an action news photograph in colour within hours of the event.37 The catalyst was a period of intense competition between the Argus and rival Melbourne papers. The Argus’s new owners, the London-based Daily Mirror group, believed colour would give the Argus a special advantage. The technology required was very expensive, so the Argus did not immediately use colour on a daily basis, but it used it regularly enough, according to newspaper librarian Chris Wade, to make it the ‘envy of the Australian newspaper world … especially when it published colour photographs for the Olympics, the Melbourne Cup and the Queen’s visit in 1954’. Circulation reportedly increased ‘by up to 25% for issues covering these special events’.38

However, the colour printers were unreliable as well as expensive, which meant that sometimes ‘printing problems resulted in The Argus missing all early morning sales as it was not distributed until after 9 or 10 am’.39 Other newspapers only began to make routine use of colour thirty or forty years later, in the late 1980s and early 1990s.40 The Argus was so ahead of its time that accumulation of debt from colour printing was one of several factors that led to its demise.41 It closed in early 1957. Also in Victoria, the Herald began publishing pre-print colour front and back covers around the late 1950s for special editions such as the Melbourne Cup or the football Grand Final. These colour covers were printed at off-set printers in the suburbs and then transported back to the HWT’s Flinders Street base for the black-and-white edition of that day’s newspaper to be added on the rotary presses.42

1.4 First colour news photographs published in Australia (reproduced in black and white). The Argus, 28 July 1952 (National Library of Australia).

The royal tour of 1954 encouraged newspapers to use more, and larger, photographs. That year, the chief photographer at the Brisbane Telegraph told a conciliation inquiry that his paper published about 6700 photos a year, on average about eighteen a day.43 Images of horseraces were a particular feature of newspapers’ expanding photographic coverage, providing critical visual information for news audiences of the day.

In 1956, the first Walkley Award for the ‘best news photograph’ was presented. The awards provided peer-reviewed, professional recognition of photographers’ work, And photographers could enter their own work or be nominated by someone else—a convention that still continues. The first winning photograph was taken by Maurice Wilmott of Sydney’s Daily Mirror. It purported to show, in a moving way, an injured veteran remembering his fallen comrades on Anzac Day. But as John Hurst explains in his history of the Walkleys, Wilmott’s editors had directed him to get something unusual that day instead of the standard images of the Anzac Day march. Wilmott saw the war widow planting small crosses and searched for a wounded veteran. He found the man drinking out of a bottle with his mates and offered him a ‘couple of quid’ if he would pose in the photograph. The man agreed so long as his face would not be shown. After the photograph was taken, Wilmott asked the man which war he had lost his leg in. Neither, the man told him. He had lost his leg in a tram accident in George Street, Sydney. Wilmott was not pleased but thought the photograph still conveyed the right message.44

1.5 Photographers at the Caulfield Cup in 1955 photographing the winning jockey, Bill Williamson, after he had won the Cup on Rising Fast. Neil Town, father of photographer Jay Town, is second from the right in the back row and was covering the race for the Herald.

Creating an impression is one thing, but in this case, the caption on the photograph blatantly misrepresented the man, describing him as ‘a disabled veteran of World War I’. The Wilmott photograph raises two issues that are central to any consideration of press photography. The first is the way in which photographers’ work is presented, which is related to their autonomy within their organisations, including their relationship with picture editors, and how their work is selected, used and interpreted. The second issue is the notion of photography as a window on ‘reality’. Newspaper readers are encouraged to view photographs as capturing an unscripted, real event. But in the 1950s and 1960s, press photographs were often arranged or ‘set up’, and so too were some of the most famous photographs of the 1970s and 1980s. Making events more presentable and fit for publication was an expectation and considered to be part of the job.

1.6 The first Walkley Award–winning photograph, photograph by Maurice Wilmott. Daily Mirror, 25 April 1956 (Walkley Foundation/National Library of Australia).

An article published in a careers supplement in the Daily Telegraph in 1957 tells ‘boys’ who aspire to a career as a press photographer that ‘frequently the photographer has to “make” a picture. This requires considerable ingenuity, news-sense, and artistic ability, in shifting both “props” and subjects into such a position that the resulting shot tells the whole story in an artistic picture that occupies the minimum of space.’45 Older photographers say that many of their pictures were set up and they had to think creatively about how to illustrate news. Later, a stronger sense of press photography as representing the ‘truth’ emerged, and this led many photographers to avoid intervening or altering a subject as much as possible, especially with hard news photographs. Veteran photographer Rick Stevens’ career coincided with this shift. He says he was trained how to set up pictures, but he ‘wouldn’t do that now’. These days, pictures ‘are taken as the event is happening in front of you’, and he dates this change specifically to ‘the early 1990s’.

Several other photographers confirm this shift in approach but make a distinction between different types of photographs. A common view is that ‘you can’t set up news pictures but most other things are set up’. In particular, portraits and social event photographs usually require some intervention. This can range from asking the subject to move into better light or closer to someone else in the photograph to requesting they perform some action or look in a particular direction. Peter McNamara, who worked for several publications including the Daily Mirror and the Courier-Mail, gives the example of ‘a handshake photo … at Queensland University. It was the top student award. So you get out there and the chancellor of the university would be all done up in his robes, and there was this girl and boy there; they’ve got their certificates. So, you’ve got them like this—the most boring photograph you could ever see … [with] absolutely no chance of getting that in the paper … So this is where a good newspaper photographer comes into his or her own right. The picture the chap actually took was … He had the Chancellor walking along … [with] his hand up … [and] the student running towards him, leaping up and giving him a high five with the rolled up … piece of paper. It just made you want to look at it … and it got used on page three.’

Several photographers on smaller, regional newspapers say that a lot of their photos are still set up because they are social pictures, or they are previewing an event or following up on something that has happened to someone. Shepparton News chief photographer Ray Sizer says that ‘95 per cent of our pictures are set up because certainly, regionally, you don’t have that option … There’s not news happening ten times a day; you can’t shoot it as it happens. You have got to create.’ Sizer also prefers ‘to employ local people when I can; if there’s two people of the same skill, I’ll always take the local one for all their local knowledge … [W]hen we’re looking for a baby for a picture … they’d say, “Oh, I know. Julie’s got a daughter, three years old. She lives round the corner.”’

At the other end of the spectrum, Verity Chambers, a former newspaper and freelance photographer, notes that ‘For the wire photographers—AP, Reuters, AFP—they’re extremely strict about arranged photographs’. Photographers who worked for newspapers before moving to news wire organisations also note this difference. Tony Ashby, who worked for the West Australian before going freelance and doing work for the news agency AFP, explains how, as a newspaper photographer, ‘You had to contrive [photographs] or they weren’t worth looking at in the paper’ whereas now, he ‘just get[s] it as it goes’, and he loves that.46 Veteran photographer Alan Porritt makes a similar observation, and Russell McPhedran, who retired after eighteen years at AAP, also insists that you could never set a photo up. ‘You would be sacked for that,’ he says, ‘whereas newspapers would pretend they didn’t know a photo had been set up.’ Former Age photographer Angela Wylie draws attention to a different dimension of set-ups, noting that, ‘in newspaper photography, often pictures are contrived in terms of trying to sell something, or are driven by press releases’.

There is also a perception that some organisational cultures are more amenable to set-ups. Several Fairfax photographers argue that News Corporation has more of a culture of setting up photographs, but the Australian’s Lyndon Mechielsen challenges that, insisting that ‘News Limited never set up hard news pictures. We just don’t do it … But stuff that isn’t hard news, there’s just this reality that you have to get a picture … [and] the eternal frustration between us and Fairfax is Fairfax take the piss out of us for [setting up photographs] but shoot the same pictures … And the wires have the same attitude, you know, “We can’t set stuff up, but we’re happy to shoot over your shoulder and do the same thing” … So, the hypocrisy is astonishing and always a source … of frustration and a defining difference between certainly the two major companies.’

There is also an international dimension to the question of setting up photographs. In 2005, Femke Rotteveel of the World Press Photo organisation stayed in Sydney for several days and was shocked by the photographs used in Sydney newspapers. According to photographer Tim Clayton, Rotteveel felt they were ‘stage-managed, set-up, old-fashioned, 20 years out of date and, above all, a lie’. Clayton suggests that editors are part of the problem and that ‘words people will understand that it is wrong to make up a quote, but feel quite happy to ask a photographer to make up a picture—to fabricate the truth, to contrive, to lie’.47

While the Wilmott photograph foreshadowed several ongoing debates about veracity and authenticity in press photography, it also foreshadowed issues of media ownership. Two years after Wilmott’s award-winning photograph, maverick owner Ezra Norton and his partners sold the Daily Mirror and other papers to the Fairfax group, which then sold them to Rupert Murdoch’s News Limited.48 By 1963, only six major newspaper owners remained.49 Consolidation, and cannibalistic and oligopolistic tendencies in newspapers had been so strong that one of those owners, the HWT, controlled approximately 43 per cent of daily newspaper circulation in Australia by 1960.50 Circulation began declining in the late 1950s,51 but large profits were still flowing from popular newspapers, and the broadsheets, with their ‘rivers of gold’ profits from classified advertising, had a particularly secure economic base.52 Television was a new rival for advertising and audiences from 1956, but the major newspapers’ parent companies owned both radio and television stations. The HWT, News Limited, John Fairfax Ltd, the Packer family company and David Syme & Co. all owned television stations by 1969.

Television’s newsgathering capacity in the 1960s was still quite primitive, and the commercial channels had little capacity for gathering overseas news.53 But by the mid-1970s, television was more advanced, including not only news but current affairs programs such as Four Corners and This Day Tonight.54 Television presented moving images of news—and entertainment—in an accessible way, which had a dramatic impact upon the newspaper industry, including upon the look, content and profitability of newspapers. Clive Mackinnon was twenty-seven years old when television came in and had been working as a newspaper photographer for ten years. He recalls thinking that the ‘television image’ was ‘too bold’ and would ‘never catch on’. But then newspapers ‘began using a bold image as well’. Early television crews were sometimes more organised in getting to jobs and setting up.55

Photographers in the late 1950s also reported that television cameras took up so much space that still photographers were being elbowed into corners, and they were also being pushed aside as the ‘publicity conscious’ gave preference to TV. They recall that with the advent of TV, they had to be more alert and ready to change their ideas about a subject or type of photograph quickly. And with the introduction of television, newspapers took to using ‘horror pictures to dramatise a particular incident and to sell newspapers’ because ‘these horror pictures were the type TV did not want’.56

Press photographers who recall the early days of television note that, to their consternation, television staff would often arrive at jobs first, and the competition between the two groups sometimes resulted in physical skirmishes. But there were also moments of cooperation. By the mid 1970s, television channels had their own helicopters—a luxury newspapers could not match, and one that gave television a terrific newsgathering advantage over newspapers. But Howard recalls how an enterprising picture editor at the Melbourne Herald organised a deal so that Herald photographers could hitch a lift in a television station’s helicopter to ‘hot news jobs’ and this would be reflected in the newspaper’s caption: ‘Bruce Howard from the Channel 10 helicopter’.57

In the 1970s, newspapers moved from ‘hot metal’ methods of typesetting to modern photo-composition, which further encouraged the use of photographs in newspapers and enabled a more ‘visual’ style of news for audiences familiar with television. By 1972, 236 of the photographers working on metropolitan daily newspapers were members of the AJA; forty-one of these were cadets. With forty-six photographers, the Victorian Herald Sun had the largest number of photographers, according to the AJA’s membership list. Computers were also arriving in newsrooms. The Herald proudly announced its new $30 000 process camera for making negatives, describing the technology as ‘modern photographic magic’.58 In the mid 1960s, photographers began switching from older, bulkier cameras to lighter, compact 35mm cameras.

But social change was also having a major impact. In 1963, Mervyn Bishop began a cadetship at the SMH, later becoming Australia’s first Indigenous press photographer. And Yvette Grady became the first full-time female staff cadet two years later. In 1977, the HWT announced its ‘first camera girl’, saying, ‘For the first time, we have a woman photographer on our staff’.59 Photographers were also moving into more executive positions. In 1971, after thirty years at the SMH, Frank Burke was made photographic manager, managing forty photographers, the first time a photographer had been appointed to manage the department.60 At the Herald, the new pictorial editor in 1973, Lester Howard, was also the first photographer to be appointed to that role.61

The 1980s saw much greater use of colour photographs, and photographers finally started receiving regular by-lines. In 1988, after complaints that the Herald’s darkroom was ‘unsafe’,62 the HWT opened its renovated darkroom, showcasing ‘dry’ printing of photographs. Camera and film technology developed at a significant pace, including high-speed film, often requiring no flash at all, and auto-focus lenses. Computers began to be used more widely at newspapers, and mobile phones also had a major impact on the work of photographers. Craig Borrow, a photographer for the Herald Sun for more than twenty years, recalls that in the old days, photographers were required to carry ten-cent pieces in their pockets, so they could use pay phones to call the office. Andrew Meares, a Fairfax photographer, observes that mobile phones have allowed the photo desk to ‘push [photographers] harder on the number of assignments per day’. Mechielsen notes that photographers can no longer ‘go missing’ as they had in pre-mobile days—a source of regret for some.

For photographers who worked on magazines, colour had become a reality decades earlier. The Women’s Weekly began publishing coloured photographic covers during World War II.63 Dennis Lingane missed out on a job at London’s City Magazine group around 1961 because he owned up at the interview to never having shot in colour, but he ended up getting a second chance. In newspapers, colour hit in the 1990s. Mackinnon, who began in 1946 and retired in 1990, never really worked with colour, only taking a few colour pictures towards the end of his career.

Guy Magowan, who worked for the West Australian, explains that during the ‘overlap from black and white to colour’, a lot of the paper was still printed in black and white, but pages one, three and five might be in colour, requiring photographers to complete assignments in both black and white and colour. This was fine for ‘a set-up picture’ but difficult for a news event, such as ‘cops chasing baddies down the road’. In those situations, photographers tended to go ‘back to the black and white because they’re not going to miss the best picture. Editors might ask, “Have you got it in colour?” But no, it’s all over by then … So in the end, the photographers were directed to “shoot everything in colour and if it’s in black and white, we’ll just scan the colour to black and white”.’64 In the awkward transition period, Neville Waller, who worked for ACP, carried two cameras because colour could be ‘very unforgiving … It was really hard to shoot colour in those days. It was technically very demanding.’ But photographers often received little or no training. Veteran photographer Bill McAuley recalls being told to ‘just put a different sort of film in the camera’ and to photograph in colour from that day onwards.65

Newspaper circulation began declining more dramatically in the 1980s and 1990s,66 and media law changes in 1986–87 led to a frenzy of buying and selling of media assets.67 Rupert Murdoch’s 1987 purchase of the HWT significantly reduced the number of independent newspaper publishers. Then, between 1987 and 1992, all of Australia’s afternoon newspapers closed, so that ‘newspaper penetration almost halved’ between 1980 and 2007.68 In the early 1990s, economic pressures on newspapers were further exacerbated when the internet started moving out of universities and into commercial and domestic use. In January 1995, the Age became the first Australian newspaper, and one of only a handful around the world, to publish an internet edition. Its first edition included no news stories or photos,69 but by 1996, the Age website was using imagery and illustrations, albeit mainly generic ones.

Slow dial-up internet connections were one obstacle to public use of newspaper websites. Another was newspaper attitudes to the online sphere. The Age’s early move to publishing an internet edition did not come from the newspaper’s management or newsroom. It was the brainchild of the company’s librarians and their interest in information archival and retrieval.70 Newspaper executives were firmly focused on the printed product and viewed the internet as a potential threat to that product and the traditional business model underpinning it.71 Many editors did not want material to be released online until it had appeared in print—including photographs. It was only at the end of the 1990s that the Age site was being updated multiple times a day and executives and journalists were becoming less resistant to updating breaking stories immediately online rather than waiting for the next day’s paper.

1.7 The Age website, 20 December 1996 (Fairfax Media).

In the late 1990s, digital cameras began to be used in Australian newsrooms, and as the quality of these cameras began to improve, major Australian news companies committed significant resources to digital. Dial-up, then bandwidth, also improved, increasing home access to faster internet and allowing for faster and greater use of content on websites and an expansion of newspapers into the online space. But, in a desktop era with very poor internet connectivity and little sense yet of how digital would work, management decisions were often still centred on protecting print revenues. The Age’s Penny Stephens observes that ‘for a long time, online existed, but it wasn’t really given a priority … It was all about the paper … [Online] built slowly over a long period of time.’

In the early 2000s, as digital cameras improved rapidly, mobile phone companies also began to produce phones with integrated cameras.72 As camera-equipped mobiles became cheaper and were more widely adopted in 2003, the news industry began to note the potential of using images taken by camera-carrying eyewitnesses.73 In May 2004, the Courier-Mail was inundated with photographs of a fire that destroyed a Brisbane bottle shop, publishing three of them, including two taken by passers-by and one taken by a journalist who lived near the hotel.74

A newspaper article in 2004 heralded a new era in which mobile phones would turn ‘accidental onlookers’ into ‘on-the-spot journalists, taking part in the newsgathering process’.75 This had potentially worrying implications for paid press photographers. In 2004, a member of the public photographed the arrest of an alleged underworld hit man and the image was published on the front pages of Melbourne newspapers, but according to Chris DeKretser, then an editor at the Herald Sun, ‘The snapper didn’t even want money for the picture—he was just doing his public duty’.76 Other citizens with camera phones, labelled the ‘snapperazzi’, did want money and began photographing celebrities in the United States and United Kingdom and selling their images to newspapers.77

After the terrorist attacks on London trains and a bus on 7 July 2005, many of the on-the-spot images of the bombings that appeared on television and in newspapers came from people who were caught up in the attacks. Underground and away from the media, they took images of what was happening using their mobile phone cameras.78 During extraordinary events, when images can only be obtained from citizens on location, such images are more likely to be used. But in many other cases, newspapers continue to send their own journalists and photographers to events to validate stories, obtain additional information and take high-quality images. The use of public-generated images marks an important shift, and one that is still unfolding, but it has not had the dramatically disruptive effect on traditional journalism that was initially predicted.79

Newspapers began to more comprehensively embrace the internet in the late 2000s, launching more detailed and more frequently updated online editions, setting up blogs and encouraging dialogue with readers. There were twelve years of development between the Age website depicted in figure 1.7 and that shown in figure 1.8. Photographs had become more prominent by 2008. Demand for mobile devices in Australia was fuelled by the release of Apple’s first-generation iPhone in July 2008 and its iPad tablet computer in 2010, along with better network coverage.80 This accelerated the phenomenon of citizens carrying camera- and video-enabled mobile devices, leading newspapers to invest more in ‘app’ forms of their online content. (Apps are specialised programs that are downloaded onto mobile devices.) These formats are also highly visual and have become multimedia platforms, incorporating videos, photographs and text.

1.8 The Age website, 5 November 2008 (Fairfax Syndication).

In 2006, Fairfax merged with Rural Press, further reducing the number of major Australian newspaper owners.81 By 2010, just two owners—Murdoch’s News Limited (now called News Corporation) and Fairfax—controlled more than 90 per cent of Australian newspaper circulation.82 Both had diversified into other types of businesses: particularly radio, magazines and online in the case of Fairfax, while News Corporation had become a major global company, with extensive interests across cable television, film, book publishing, sport and online. Both companies now made significantly more money from the non-newspaper areas of their businesses.83 Newspapers were no longer the well-resourced, highly profitable and prestigious enterprises they once had been.

Advertising—not the cover price—had always paid for the newspapers’ production of content, and advertisers had been lured to the internet by cheaper and more targeted alternatives to display and classified advertising. A different kind of advertising competition was also affecting newspapers online, with Google, Yahoo, Microsoft and sites such as Wikipedia, Amazon and eBay ‘capturing the lion’s share of traffic that can bring in ad money. And none of them has expensive newsrooms to feed.’84 The financial position of newspapers significantly deteriorated in the 2010s. Between 2011 and 2013, both News Limited and Fairfax erected online paywall subscription models for their products.85 After nearly two decades of giving online audiences content free of charge, newspapers were now trying to get their audiences to pay for it. But the revenue raised from this strategy was not enough to prevent a series of redundancies and job losses, which saw hundreds of newspaper staff, including photographers, depart the industry between 2009 and 2015.86

While these changes were occurring on the economic and business side of newspapers, mobile technology was extending what was possible in terms of production and access. In 2010, Meares won a Walkley Award for photographs of the 2010 election taken on an iPhone. He observes that the advent of mobile devices that can be updated and carried around has been a ‘game changer’ for news audiences and, therefore, for news executives and their approach to online. With the decline in print revenues focusing management’s attention on future revenue streams, new formats began to be explored, such as ‘The Pulse’, Fairfax’s live blog from question time in Canberra, which began in 2011. By 2015, photographs taken by Meares and Alex Ellinghausen were a core part of that live blog from Parliament House, which also includes video, text, links to other stories and, running down the right-hand side, comments posted by readers.

1.9 ‘The Pulse’, Sydney Morning Herald website, 11 August 2015 (Fairfax Syndication).

By 2015, only eleven daily capital-city newspapers were left. One is owned by Seven West Media. The other ten are owned by either News Corporation or Fairfax. A variety of new media players are also delivering news and commentary online in competition with newspapers and newspaper websites. This includes overseas newspapers that have established online-only websites in Australia, such as the Guardian and the Daily Mail, but also new players such as the Huffington Post, as well as websites controlled by entities that have traditionally been the subject of news (and photography) but that now report news themselves, such as AFL Media.87 Some new Australian players did not last very long, such as the Global Mail. Others, such as Crikey and New Matilda, have small subscription bases, few salaried journalists and no salaried photographic teams. These dramatic shifts in the newspaper industry have led to significant concerns about the future of press photography.

Photographers in the two remaining large newspaper companies see advantages and disadvantages in the photographic style and corporate culture of their competitors. There is also a sense that culture and approaches are influenced not just by the newspaper organisation but also the type of newspaper. For regional newspapers or those in smaller cities, locality matters. Karleen Minney of the Canberra Times says: ‘The bigger papers, because their reach is a much larger population, they can’t be specific because nobody’s interested in this one person in this one town. But in a smaller area like ours … you can draw everybody’s interest ’cause they probably are only a couple of degrees separated from that person … so you can, sort of, hone in and get a little bit tighter and a little bit more local. And by the same token … you have to be that little bit more careful that you’re not giving away too much, or you’re not getting too personal … because there are so many connections and strong relationships that you have to be kind of careful [not] to tread on.’

Grant Wells, formerly of the Advocate in north-west Tasmania, recalls a colleague who was off duty when a car crashed and burst into flames outside the wedding venue where he’d been taking photos. He got some incredible photos of the car on fire but also some abuse for it afterwards, as there was a person inside the car while it was on fire. It ‘wouldn’t have caused a stir if it was in one of the daily metros. But in a smaller community, you know who the person is. That’s a point of difference in how [local papers] cover things.’

Papers that are national, or specialist, such as the Financial Review, can have different emphases and styles. Lorrie Graham, for instance, recalls that the National Times ‘was a ratbag of an [organisation] … a very brave little … paper within an organisation that allowed it to be that … It did an incredible amount of investigative journalism. It pushed the envelope quite a bit when it was going after people. And it did in-depth stories, great in-depth stories. It wasn’t always right. And it wore a lot of shit from the other publications. But it was a very small, tight unit … I could come up with ideas.’

Aside from issues of autonomy, there are also thought to be key stylistic differences between tabloid and broadsheet newspapers. Fairfax was traditionally a broadsheet publisher, while News Corporation grew from large-circulation tabloid newspapers. Broadsheets use a mix of photographs, some of which are human-interest oriented, quirky or engaging, to contrast with the ‘shock horror’ of hard-news stories. But tabloids are perceived to have a greater need for such content and a distinct photographic style. Minney notes that tabloid photographs ‘seem a little … brashier, a little more stylised and bright and in your face … And in a broadsheet, it feels like it’s a little more … historical and a little more general and a little more environmentally telling a story not just with a subject.’ But the distinctions between tabloid and broadsheet photographs might be breaking down. Both newspapers are now more engaged in the online space, and in 2013, the Age and SMH overturned more than one hundred and fifty years of tradition when they moved to a ‘compact’ size, so that Fairfax could save costs. The new size was deliberately promoted as ‘compact’ rather than ‘tabloid’ because of the ‘sensationalist’ overtones associated with the term ‘tabloid’. Fairfax assured its readers that the change in size would not shift its content downmarket and that its papers would remain serious and thoughtful.

Herald Sun photographer Jay Town argues that ‘There’s a big difference between the set-up, cheesy, tight and bright Herald Sun–type [photograph] and then the nice, broadsheet Age picture—well, back when the Age was a fantastic broadsheet that could really showcase their photographers’ work.’ Town recalls how someone from the Age said to him twenty years ago, ‘“You could never work at the Age. You could never take our sort of pictures.” … I remember being really offended at the time but now I think about it, well … they’ve probably got a good point … I see things the way I shoot. I’ve had a few people say to me … “You’ve got the Herald Sun formula down pat, the way you shoot.” I’ve never shot to the Herald Sun formula; I just shoot to my formula. It just so happens that that’s what the paper likes or runs: … someone cuddling a dog … [the] kid kissing the rabbit … That’s what I like to do.’ Town says that he’ll ‘look at say some of the stuff that Jason South would’ve done … in the Age and … go, “Oh, that’s just fantastic. I just wouldn’t have thought of that.” It just drives me nuts … I just love it and I think, “I never would have got that.” I would’ve gone in there and [tried] to do the tight and bright thing … [But] there’s pictures getting in our paper now that never would’ve gotten in ten years ago because things have changed … And the opposite’s happening with the Age now that they’ve gone … compact; they’ve had to adjust their style.’

In the 2010s, as newspapers searched for content that was ‘clickable’ online, new demands were made of photographers. As the YouTube phenomenon fostered a culture of watching short videos online, there also became ‘a lot of pressure’ for photographers to provide photographs and video, which put strain on photographers ‘in certain news situations to be able to do that’. Some describe feeling pressure to take photographs on their phone for online and hating it because ‘you could miss a good picture’ on the ‘good camera while you’re trying to muck around doing a [phone] picture and you’re not going to get the same angle again’.

Town recalls how ‘a couple of years ago we were getting pushed hard into doing video as well as stills … Video just doesn’t hold for me at all … I’ve got no interest in doing it whatsoever. But we were getting pressured all the time to do it.’ More recently, newspapers seem to have stopped that push, having found that video was not cost-effective or delivering the audience results they hoped for. Some photographers, though, enjoy the possibilities of new media, and not least because, they say, multimedia formats offer diversity, autonomy and their voice as narrators. But the experience is salutary for others, like Town, who has realised that what ‘he loves about photography is its ability to ‘freeze time … You can’t do that with video … It’s all about timing and capturing it just as it is and then stopping it and then you’ve got it forever.’

Technology has dramatically shaped how press photographers take and deliver their photographs to news audiences, but technological change has to be seen in conjunction with significant shifts in other areas as well, including shifts in journalism, news audiences, changing newspaper styles and formats, news values, newspaper production routines, media ownership, industrial relations and working conditions, the economic fortunes of newspapers, and shifting attitudes towards photographs and their role in reporting and understanding news.

No matter which technology is used to take them, photographs have come to occupy a central place in print and online news journalism. Waller argues that ‘People are so visually oriented and need to see the picture.’ This is not only about photographs adding to textual information or providing a visual account of some event. As retired photographer Barry Baker points out, good news photographs ‘provoke an emotion or reaction of some sort’.88 Several photographers also argue that photographs are what attract the eye and encourage people to actually read news stories. Veteran photographer Bruce Postle found that ‘If there was a great picture on the front of the paper, you could tell immediately. You [would] walk into the … newsagent … and there’d be no papers left.’89 Canberra Times photographer Graham Tidy explains that ‘Even journalists will say, “We’d never get our stories read unless there was a terrific image to go with it.”’ Academic research supports photographers’ conviction that images draw readers to news stories.90 But beyond the undoubted commercial value of photographs to newspapers, photographers also speak eloquently of photographs as powerful instruments, more likely to be instilled in memory than moving images, and able to change world events. As Ashby observes, ‘Terrible things can be beautiful pictures.’91