SALLY YOUNG

PRESS PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO are tasked with photographing politics face some unique challenges. Many aspects of politics—including policies, laws, negotiations and the work of the public service—are more abstract in nature than a clearly visual news event, such as a fire or car accident. Nor does politics generally have the commercial news appeal of other types of photographs, such as sport, entertainment or celebrity images. Indeed, among news audiences, interest in politics may be low. There is also the important visual problem of how to represent, in an interesting and engaging way, what has traditionally been a world of middle-aged white men in suits. And while there is a range of institutions involved in politics—including parliaments, governments, the public service, lobbyists, authorities, councils, advisory committees and courts, to name a few—not all of these are accessible, or their work easy to capture visually.

Since the 1960s, Australian political reporting has emphasised the two major party leaders as symbols of politics, especially national politics. In both written and visual journalism, these party leaders tend to be used as a form of shorthand for politics more broadly. This personalisation has made the nature of leadership a key theme in political photographs. Potent and iconic photographs of politics have an impact upon political conduct in a way that is quite unique compared with other spheres of press photography. This is because politicians are not hapless, temporary or accidental subjects of news photographs in the way that a victim of crime or a train derailment is.

Politicians and their advisers spend a great deal of time, effort and money on political public relations techniques, including how they appear visually. They analyse media coverage intensely, accruing an institutional and historical store of knowledge and memory within party organisations. They also monitor how press photographers work and the impact of the photographs they publish. On the basis of what they learn and observe, politicians are constantly adapting the way they practise politics—including how they govern and campaign. They change their focus, strategies and routines, and increasingly try to circumscribe the boundaries of what can be photographed. In turn, photographers modify their working practices, including how they use new technology, to try to get around those constraints. The relationship between photographers and politicians is cooperative, competitive and reactive, and the constant interaction between the two groups influences how they carry out their work.

One of the most important political photographs in Australian political history had a major impact upon both politics and press photography. In March 1963, the Labor Party’s federal conference met at the Kingston Hotel in Canberra. Labor leader Arthur Calwell and his deputy leader Gough Whitlam were not delegates to the conference, which at that time consisted of six delegates from each of the six states. The conference was deciding an important question of policy that was taxing Labor’s leadership: whether Labor would support moves by the Menzies government to allow US bases on Australian soil that could be used to control nuclear-armed submarines. Menzies was using the issue to wedge Labor. Having won the 1961 election by only one seat, he needed to shift the focus away from domestic issues (where Labor was perceived more favourably) and on to issues of security and defence, where his own party was seen as more successful. Calwell and Whitlam were in favour of the bases. Both addressed the conference and then retired to Parliament House. After debate and deadlock among the delegates, the final vote was cast at 1.45 am. By this point, Calwell and Whitlam had returned to the hotel, and although Calwell could have gone back inside, inexplicably he chose to wait outside with Whitlam to find out the result of the final vote.1 The two men stood outside under a street lamp with conference delegates occasionally coming out to confer with them and update them on the progress inside.

When the astute political reporter Alan Reid spotted Calwell and Whitlam waiting impatiently outside, he saw a great opportunity and knew that a photograph was essential. Reid went on to become a legendary political reporter, covering politics from 1937 to 1985. He was also a faithful employee of Frank Packer, the conservative owner of the Daily Telegraph, TCN9 Sydney, GTV9 Melbourne, the Women’s Weekly and several other magazines and radio stations. Reid’s biographers, Stephen Holt and Ross Fitzgerald, have written that as Packer’s chief journalist in Canberra, Reid was given a brief ‘to depict the ALP conference in as unfavourable a light as possible’ to represent Packer’s interests in supporting Prime Minister Robert Menzies.2 Reid had originally planned to write a story about the ALP’s disunity over the US bases, but the two leaders huddled in the street presented a better opportunity to show Labor as weak and vacillating.

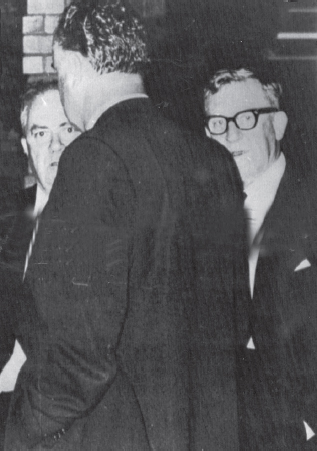

6.1 One of the ‘faceless men’ photographs, published in the Daily Telegraph, 22 March 1963. Photographer not cited, but probably Vladimir Paral (News Corporation Australia/Newspix).

There has been a longstanding debate about who took the famous ‘faceless men’ photographs, with the late Peter Hardacre, then staff photographer at the Daily Telegraph, often considered the most likely possibility. However, Reid’s biographers have published a more convincing account, arguing that they were not taken by a staff photographer.3 Fitzgerald and Holt describe how Reid had been frustrated when he could not summon a staff photographer at that late hour of the night but then noticed that one of the observers who had shown up at the hotel was a friend, fellow trout-angler Vladimir Paral. Paral happened to work as a scientific photographer at the John Curtin School of Medical Research. Reid asked him to rush home and get his camera and not to worry if the shots did not flatter the subjects. Paral developed his rushed shots in a darkroom at the John Curtin School and met up with Reid a few hours later in King’s Hall. Reid had the photographs sent to Sydney on the first flight out of Canberra.4

The visual imagery was powerful. There was something compelling about seeing party leaders standing out on the street, in the dark, furtively conspiring with party delegates and anxiously ‘awaiting instructions’ on what policy they would take to the electorate. The undisguised clandestine nature of the photographs added to their impact because they were taken outside of the usual, official, sanctioned settings of political photographs at the time—parliament and official events—in an almost paparazzi style. The images potently evoked weak, indecisive and undemocratic leadership. They were no accidental scoop but an exercise in media power—part of the machinations of Frank Packer and his formidable journalist. Since Reid had organised for the photographs to be taken, the selection published fitted his story. Left out, for example, was a photograph of a smiling Calwell after the vote went his way.

On the back of the Reid story and Paral’s powerful photographs, the Liberal Party produced a leaflet reproducing the most famous of the photographs and describing the Labor delegates as ‘36 unknown men, not elected to Parliament nor responsible to the people’.5 The implication that Labor’s leaders were not in charge of party policy was devastatingly effective. The Liberals called the election a year early and the ‘faceless men’ episode was widely seen as a significant factor in the Liberal Party’s electoral success in 1963 and even 1966.6 Gough Whitlam called the episode ‘a devastating blow against us’,7 using it as a catalyst for internal reform of the party’s structures. The photographs had an impact that is felt to this day, with the ‘faceless men’ tag still used frequently against the Labor Party, including during the party’s leadership crises in 2010–13.

The faceless men photographs taught Australian politicians an early lesson in the importance of being aware of visuals and of how things might appear. They would need to be on guard always, as a photograph could be taken at any moment. It seems Paral’s identity was kept secret for so many years in order to protect him—Paral’s use of his research school’s facilities to print the photos was against its rules. His pictures changed photography for the same reason they changed politics: they revealed the power of the unauthorised image, and have led press photographers ever since to try to capture what politicians do not want them to see.

The ‘faceless men’ photographs evoked weak leadership, but nine years later, one of the subjects of those photographs, Gough Whitlam, was photographed in a way that captured instead the essence of charismatic, popular leadership. Whitlam had become Labor leader in 1967. By 1972, his party was within sight of returning to government after twenty-three years in Opposition. At the campaign launch at Blacktown Civic Centre, Rick Stevens took a front-page photograph that captured the ascendant leader in a way that dramatically evoked a sense of imminent victory. The photograph has royal and biblical overtones, conveyed in Whitlam’s gesture and the woman’s reverence. The lighting and the photographer’s vantage point, from up on stage, add to the impact of the photograph and show how photographers were, at this point, becoming more physically central to the action of politics. Stevens gained a different visual perspective on politics that was closer to the leader’s viewpoint, looking down upon the crowd.

Stevens had deliberately moved away from the others in the media pack and gone up on stage because ‘I wanted to show Gough with people rather than looking up his nose from below.’ The lighting was different by accident rather than design. Stevens squeezed off a few frames but his flash didn’t work. As a young C-grade photographer, he panicked a bit because he didn’t know if he had captured anything: ‘in the days of film … you [couldn’t] look at the back of the camera to see what you’ve got’. Stevens explains that ‘if the flash had’ve gone off, it wouldn’t be as good a picture as it was because the flash … would have killed the atmosphere around it … [and it] would have probably just been Gough and the woman and the background would have been dark. Somebody was on my side that day … I don’t how many times I’ve put the film in the developer and I’ve sat there and developed and said, “Please be good, please be good, please be something on there.”’ Stevens won the Nikon Best News Picture of the Year Award for the photograph but recalls that ‘even though it won a major award, the picture editor … said it wasn’t that good. He didn’t want me to get a swelled head.’

6.2 Dorothy Scott kisses the hand of Gough Whitlam as he opens the Labor Party election campaign at Blacktown Civic Centre in Sydney, 13 November 1972. Photographer Rick Stevens, published in the Sydney Morning Herald, 14 November 1972 (Rick Stevens/Fairfax Syndication).

Whitlam’s one-time bitter opponent, Malcolm Fraser, was also the subject of important photographs that focused on the nature of leadership. Fraser was shown addressing large rallies around Australia in 1975 following the controversial dismissal of the Whitlam government. Open political meetings were regularly held in the 1970s and 1980s, including rallies and town hall and lunchtime meetings. These events visibly conveyed interaction between leaders and the public and allowed photographers to capture crowd scenes, interesting visuals and unscripted events, including placards, cheering, shouting or other forms of dissent or support. But Fraser was also the subject of photographs that captured the personal highs and lows of leadership. The emotion conveyed in these images is particularly striking because Fraser was often characterised as being aloof and unemotional.

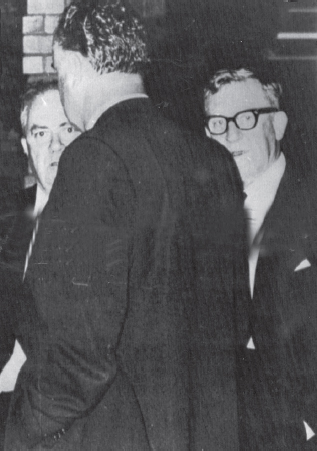

Bruce Postle’s famous photograph of Malcolm Fraser reading the newspaper in bed at the Windsor Hotel the morning after he retained office at the 1980 election is one of those photographs. Today, such a risky shot would be carefully managed by advisers, if it were allowed at all. Back then, the image reflected Postle’s unique approach. Famed for his ingenuity and for seeing a potential front-page photo in every job he was given, Postle worked for the Age from 1969 to 1996. He was artistic and creative in his approach to photographing the news. He saw himself as not just an observer or recorder of events but as ‘a director of what might be’.8

Postle had asked permission several times to photograph Fraser in bed but had been denied approval. The ‘idea of this tall, supposedly remote man in such a personal setting, between sheets and blanket’ appealed to him. On this occasion, Fraser agreed, and Postle was allowed a few minutes in the bedroom. He collected the newspapers on his way there. Mrs Fraser kept well out of sight so she wouldn’t appear in the photograph. Postle recalls how, when Fraser’s son rang to congratulate him, Fraser dropped the papers, threw his head back and smiled, so ‘I shot that picture [as well].’ The ‘one they used on the front page of the Age was the serious one of him sitting there reading … but I liked the other one much more, which they used on the day he died’.9

Winning three elections, Fraser was viewed as a strong leader who had a reputation for being not only ‘aloof’ but ‘arrogant’. This made a photograph published in the Sydney Morning Herald on the night Fraser lost the 1983 election to Bob Hawke especially poignant. Taken by Paul Wright, the photograph shows Fraser with his head bowed, crying, his face visibly contorted. It was a humanising image that vividly captured the vulnerability and disappointment that even a hardened political warrior can feel. It won Wright a Walkley Award in 1983. But another photograph, by Postle, was never published, and that illustrates the pull of human connections and the judgement calls that photographers make. Postle was again allowed into Fraser’s Windsor Hotel room the morning after the 1983 election, when Andrew Peacock was also there, and Fraser told him that he could photograph whatever he wanted. But Postle judged that Fraser ‘was still in shock … I mean he was still in his bloody pyjamas and you could see him head-to-foot in this picture. I took that picture, but I wouldn’t give it to the Age. They would have run it, but I had too much respect for the man … I actually cut the negative up.’10

6.3 Malcolm Fraser relaxes in bed at the Windsor Hotel after winning the 1980 federal election. Photographer Bruce Postle, published in the Age, 26 November 1980 (Bruce Postle/Fairfax Syndication).

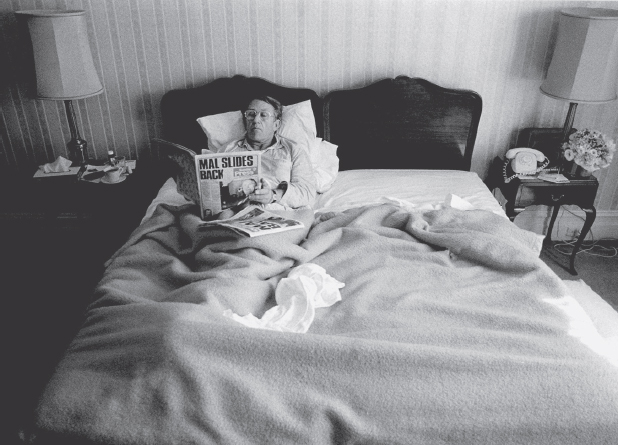

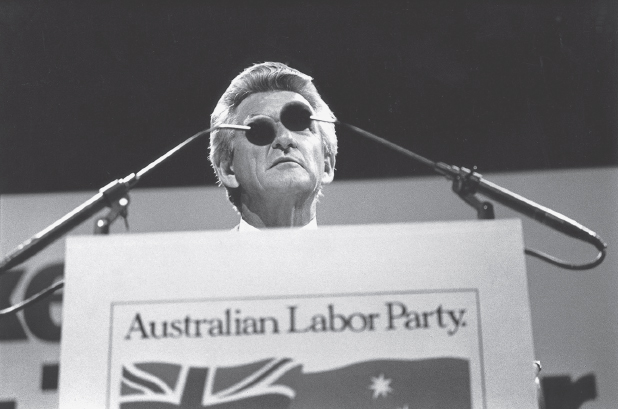

Vivid images are often the result of hard work and creative thinking on the part of photographers, rather than a result of pure chance. And not all political images relate to pathos, suffering or triumph. Lorrie Graham’s photograph of Labor leader Bob Hawke with two microphones covering his eyes conveys humour and whimsy. Graham was working in 1983 for the National Times, a weekly, and felt she ‘had to produce something different from photographers working on the dailies. A shot that was strong enough to work days after the event’. She saw the potential of this shot ‘the minute I walked into the opera house’, but while ‘everybody sort of assumes it was … such an obvious shot’, it took Graham all day to get it. She had to crawl around the floor and ‘manoeuvre my way around the entire opera house to get the position to get it. And it’s only one frame that it’s perfectly [lined up].’11 It took three and a half rolls of film to get the one frame where the microphones covered Hawke’s eyes.12 The resulting image of an insect-like Hawke led politicians and their advisers to tighten control of public appearances even more, and to pay more attention to the physical surroundings of photo opportunities.

6.4 Bob Hawke launching Labor’s election campaign, 1983. Photographer Lorrie Graham, published in the National Times (Lorrie Graham/Fairfax Syndication).

At other times, great images do result from chance. Peter Wells’ photograph for the Canberra Times capturing the moment that Hawke’s glasses were smashed by a cricket ball is a case of the photographer being in the wrong place at the right time. Wells had stood behind the batsman, a spot that photographers would normally avoid because it usually yields only a view of the sportsman’s back. But in this case, it turned out to be precisely where the best shot of Hawke could be snapped after Hawke tried to hook a ball during a social match. The dramatic photograph of a stricken leader at the moment of impact, his glasses smashing, resulted from a confluence of timing, vantage point and luck. The image also reflects a shift towards more candid images and action shots.

Hawke was a political leader who displayed an unusually emotional side. He cried publicly on several occasions but also exhibited joy and, at other times, overt anger. Photographs of Hawke crying were studies of vulnerability and grief that challenged traditional notions of stoic, masculine leadership. Some of the most striking were taken by several photographers in the Great Hall at Parliament House at a memorial service for the victims of Tiananmen Square. Graham Tidy recalls how the ‘television lights were sort of beaming down on [Hawke and] … tears started rolling down his cheeks and then … his nose started to run’. About four photographers present began ‘elbowing each other’ as Hawke’s tears flowed. Because the stage was ‘backlit, there was a big stream of snot coming out of [Hawke’s] nose and we’re all firing away there’. The photographs captured an outpouring of grief and a moment of emotional abandon, as snot cascaded from Hawke’s nose and landed on his expensive suit.

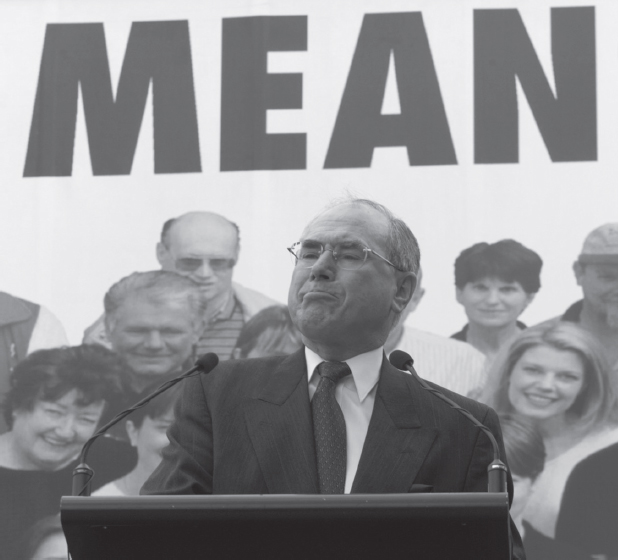

For a photographer, many small factors can make a large difference to the impact of a photograph. A split second, a shadow, a slight angle or a choice about whether to use a flash can all affect the final image. In 1996, Liberal Prime Minister John Howard addressed a hostile pro-gun rally in Sale, Victoria, after he had introduced a policy to buy back semi-automatic weapons following the Port Arthur massacre in Tasmania. Both Andrew Meares of Fairfax and Ray Strange of News Limited took a photograph at almost the same moment, but in Strange’s photo, the outline of a bullet-proof vest was clear, whereas in Meares’ photo, it was indistinct. Both conferred afterwards, wondering if the photograph showed what they thought they could see. They contacted Howard’s office and asked if he was wearing a bullet-proof vest. They were told that he was not. His office later said their advice had been technically correct because Howard was wearing a ‘ballistics vest’ not a bullet-proof vest. The semantics taught Meares ‘important lessons’ about how ‘the prime minister’s office treat the media and how we should treat them’. It was becoming less common for politicians to address large crowds, so the image conveys Howard’s bravery in doing so, but at the same time, the vest suggests a lack of trust in the crowd, a distance from it, and a sense of insecurity and potential violence, all of which have undemocratic overtones.

6.5 John Howard addressing a progun rally in Sale, Victoria, 16 June 1996. Photographer Ray Strange, published in the Herald Sun (Ray Strange/Newspix).

Howard’s demeanour was different from that of Hawke, who had been emotionally expressive and seemed to court and enjoy the TV and press cameras. While Howard was professional and courteous with photographers, his preferred medium was radio, and for several years during his time as prime minister, the standard shot of political activity became a shot of Howard in a radio booth doing an interview. Howard was not as interested in supplying expressive, risqué or novel treatments of leadership. While Howard was more naturally cautious and conservative in manner, his tenure also coincided with an increasing awareness of political public relations techniques and a tightening of access to political leaders.

Politicians and their advisers are especially concerned with image control and stage-management during elections, when the political stakes are highest. During the 1993 election, Liberal leader John Hewson held a series of lunchtime street rallies in the final days of the campaign. TV footage of protesters shouting abuse at Hewson (and him shouting back) was damaging as Hewson appeared to be mired in chaos and lacking control. His election loss was fresh in political advisers’ minds during the highly competitive 1996 election campaign. Both major parties put in place new logistical arrangements for the press ‘pack’ travelling with party leaders.13 By providing transport, the parties were able to keep the leaders’ daily schedules under tight wraps. The accredited media representatives on the campaign buses and planes were kept in the dark about where they were going and taken to locations for campaign events with little notice. They dubbed it the ‘magical mystery tour’.14

As the parties’ campaign teams moved away from the large public gatherings that had stung Hewson, they focused on setting up more controlled appearances at shopping centres and schools, as well as smaller pre-arranged events at selected businesses, hospitals, childcare centres, farms, factories or family homes (often a party supporter’s house). While politicians and their advisers wanted election campaigns to be as controlled as possible, they still needed to supply a steady stream of visually interesting material for newspapers and television.

Over the next few election campaigns, the secrecy and control of the campaign teams intensified.15 At the same time, the technology used by journalists and photographers was improving dramatically. In the 2000s, advances in digital equipment and satellite technology enabled photographers to transmit audiovisual material back to base quickly and wirelessly, allowing photographs to be published with greater speed and efficiency. By the 2010s, photographs could be sent from Blackberries, mobiles, iPads and laptops, and could be posted on blogs, Twitter or photo galleries.

The move to digital photography was not merely a technical shift though. It expanded opportunities for photographers, and left politicians scrambling to adapt. Prior to digital, politicians were used to working with photographers to get an image, one that was more likely to be positive as a result of it being a collaborative effort. When thinking about the impact of digital during his nineteen years in the Canberra press gallery, Meares recalls an incident in the early days of digital. John Howard was scheduled to give a speech at a venue in Gosford but couldn’t because it was a polling place. Meares, using a digital camera, quickly took a picture of the empty podium and sent it to the online department of his newspaper, who rapidly wrote a short story on Howard’s absence. Prior to digital, Howard would pose for photographers because he knew that getting a good picture in the newspaper was favourable to him. But with digital cameras, Meares realised photographers ‘no longer had to play by those rules’; they could quickly capture images of off-guard moments, ‘the set-ups … critical pictures … documentary pictures … it really opened up everything I could possibly see and translate into an image’.

The shift to digital allowed much greater opportunity for photographers to capture images without the cooperation of politicians and their staffers. The work practices of the prime minister’s office, and the offices of other senior politicians, changed as a result. They thought far more about which aspects photographers were going to accentuate. They limited access, provided more controlled photo ops, more sanitised venues, backdrops and visuals. They devoted more resources to crafting visual moments for news organisations, particularly after Labor’s visually oriented ‘Kevin 07’ campaign in 2007. Mike Bowers describes Kevin Rudd as ‘the most camera-aware politician I have ever met in my life … [H]e just had the ability to draw the camera to him’—and away from other politicians. Visually significant moments from the 2007 campaign included Rudd holding up a laptop at a press conference when promising new laptops for school students, visits to farms, schools and factories, and Rudd surrounded by young people in ‘Kevin 07’ T-shirts. These competed visually with Howard’s patriotic green-and-gold tracksuit worn during his morning walks.

Political scientist Rodney Tiffen points out that ‘the media maintain the pretence that they are reporting a[n election] campaign which exists independently of them, when in fact the primary purpose of those campaign activities is precisely to secure favourable news coverage’.16 Or as one photographer says, ‘Elections are not really for the public; they’re for us [the media].’ Photographers want images of politicians interacting with members of the public, and politicians and their advisers know this and try to facilitate it through set-up events, but spontaneity is difficult to achieve. Some photographers note that when an event is held in a public place, it is very daunting for an ordinary member of the public who happens to cross paths with a politician followed by a pack of photographers, camera crews and journalists.

The ordinary shopper who is walking through a shopping centre and happens upon a frenzy of cameras is often overwhelmed. And any member of the public who does want to speak to the politician can find they are jostled, crushed or knocked down in the scrum. After nearly four decades in the press gallery and having covered many elections, Alan Porritt observes that sometimes ‘the public do get upset because [the media pack is] in the way’. But Jason South notes that the presence of so many cameras also has a visual impact. He describes the photo opportunities that Australian politicians create as ‘always [looking] crap’ and a ‘mess’, with cameras everywhere, whereas ‘they don’t shoot it like that in America’, ‘the Americans do it amazingly’ because ‘they provide spectacle’. Pool photography (where a single designated photographer provides images to all other media outlets as well as their own) is one way that is achieved in the United States, but it is a control mechanism several campaign photographers say they are loath to see introduced here.

The Australian media have been increasingly willing to critique the way election campaigns are staged for the media, as opposed to the public. As campaigns have become more sanitised, journalists and photographers have been narrating events to reveal what is going on behind the pictures. To take just one example, in 2007 Michael Gawenda reported that a campaign event, a barbecue Rudd was ostensibly cooking for families at an event in Perth, was entirely staged. Half-cooked sausages were put on the barbecue when Rudd arrived; a car arrived with the ‘families’, who were then assembled around the barbecue; pictures were taken of Rudd talking to the families and, once this was recorded, the barbeque was switched off, the sausages put back on a tray and the families driven away in a van. No one ate the sausages!17 There has been a marked shift towards this sort of ‘meta-coverage’ in election reporting, where journalists report on the behaviour and performance of the news media and how election candidates interact with the media.18 This ‘meta-coverage’ is also visual and has seen the cameras zoom out from focusing on the candidates to wider shots that draw the viewer’s attention to how the candidates are performing for the cameras. Freelance photographer Andrew Chapman’s image of Kim Beazley in a fish market during the 1998 election reflects this phenomenon, in the way it draws attention to the media’s own role in election campaigns.

6.6 Kim Beazley during the 1998 election campaign at the Sydney fish market. Photographer Andrew Chapman, published in Campaign, Tandem Publishing, 2007 (Andrew Chapman).

Porritt, who spent thirty-eight years in the press gallery, and flew 48 000 kilometres during the 2013 election, says that covering elections is ‘tiring but can be a lot of fun’. The most difficult aspect is clothing because ‘sometimes you don’t stay in places where you’ve got washing machines. So you’ve got to take enough clothes … to last you ten days … If they’ve got a washing machine, you end up at two o’clock in the morning doing your washing … it’s just full on’. Meares notes that for photographers, an election involves ‘a lot of travelling and a lot of waiting around, and then short bursts of access to the candidate’. Chapman agrees that ‘there is a hell of a lot of waiting around’, ‘boredom’, ‘theatre’ and ‘crap’, but at least ‘when a politician has to go and bare their soul to the real people … the possibility exists that everything’s going to go off message … and that’s what the press love about it’. Angela Wylie notes the changes that have occurred in terms of spontaneity, saying that she ‘loved shooting pollies … It used to be much more real … You never used to know what was going to happen … Politicians walking down the street, or if it is a press conference, they can’t really hide’ and she liked ‘being able to find that in their face or in their body language’. But that has changed as it has become ‘extremely stage-managed’.

Ironically, this has made photographers hyper-vigilant. Meares says that at staged events, the photographers are ‘eagle-eyed for what goes wrong or what pulls away the curtain of that staged event … Australian political photography is quite unique in that way.’ He recalls a picture he took of Kevin Rudd at a Puffing Billy train station, where the focus was supposed to be on Rudd meeting ordinary people, but the image Meares chose to use instead was of Rudd driving away—‘a moment where he’d dropped his guard’.

While politicians make determined efforts to control how they appear, they cannot control everything, and incidents occur that confound their attempts to convey the stability, control and dignity befitting a political leader. In 2012, Lukas Coch won a Walkley Award for a photograph of Prime Minister Julia Gillard being dragged out of a restaurant by her security detail in Canberra on Australia Day. Gillard and the then Opposition leader Tony Abbott had been at the restaurant for an Australia Day citizenship ceremony when protesters came across from the Aboriginal Tent Embassy. Abbott had made comments that morning that had inflamed tension about how Indigenous Australians should view Australia Day. The restaurant had glass windows all around, so Abbott and Gillard could be clearly seen from outside. As the protesters began banging on the windows and shouting, it threatened to escalate into a security situation.

From outside, Coch saw the prime minister’s car move into place and her security staff inside. He tried to anticipate what might happen, but he did not expect that ‘they would run out and try and flee’. He was close to the door as they rushed out, and although Coch didn’t really look through the camera, he had pre-set it for the light and so randomly took a few pictures as best he could in the commotion. He was unsure if he had managed to get anything, but his image was used around the world. Other photographs showed that Gillard had lost a shoe in the melee, adding to the symbolism of the photographs.

Coch notes the symbolism and how the image conveys multiple meanings because it is an image of Australia Day, and because a female prime minister is being ‘kind of dragged … [by her] bodyguard’. The way he is carrying or dragging her speaks volumes about power and gender relations. There is also ‘the idea of the fairytale, like Cinderella, losing her shoe, [and] that you shouldn’t throw stones if you are in a glass house’. In the photo, Gillard also ‘seems a little bit scared … people were running … people stood in front of the car … banged on the car’.

Photos that capture vulnerability in political leaders—Fraser and Hawke crying, or Hawke’s glasses shattering in his face—clearly represent something potent that breaks through the carefully crafted images leaders usually provide. Meares notes that there is something about leaders’ suffering, generally, that resonates. But the images of Gillard also have a gendered dimension, because they suggest her reliance upon the man protecting her, and physically manipulating her in a way that touched a nerve.

6.7 Gillard and Tony Abbott being escorted by police and bodyguards out of a citizenship ceremony in Canberra, 26 January 2012. Photographer Lukas Coch (AAP Image/Lukas Coch).

By contrast, Tony Abbott, like Russian President Vladimir Putin, created many opportunities for photographers to take sanctioned, masculine action shots of him cycling, swimming and, infamously, wearing tight Speedo bathers dubbed ‘budgie smugglers’ in Australia. When he became prime minister, Abbott publicly vowed to forego the Speedos but continued his action-man events, which meant photographs of him swimming, working out and running still appeared regularly. Through such images, Abbott was able to portray himself as strong, fit and active, as opposed to images of him wearing glasses and reading, even though these more studious activities may represent a more ‘truthful’ or ‘real’ image of him.19

Press photographers are sometimes complicit in building a politician’s profile or image. This can be unintentional, or the photographer may be aware that the politician is using them to deliver a visual message, but the photographer may also be benefiting from that relationship through close access or exclusive opportunities. During media speculation about a possible leadership spill against Prime Minister Tony Abbott in 2015, one of his potential challengers, Liberal deputy leader Julie Bishop, seemed to be consciously building a public profile through photography, perhaps because she could ‘convey a lot [in images] without … undermining the leader through words’.20 Photographers were invited to photograph Bishop running, and there were some well-publicised photographs of her running overseas, including in Burma and in China, where her Chinese security guards had to run in their suits and ties to keep up with her.

Many political photographs show events that are either staged for photographers or instigated by them. From the politicians’ point of view, these are attempts to represent their leadership qualities in a positive light. But this goal clashes with the desire of the Australian media for ‘gotcha’ photographs, which draw attention to the errors politicians and their advisers make and humorously or irreverently pierce the stage-managed facade. In 1987, John Howard was photographed behind a too-tall podium, dwarfed by the microphones. The Liberal Party’s campaign slogan on the front of the podium read, ‘Get in front again’. This ironic juxtaposition reportedly led to Howard having his own podium, set for his height, sent with him as he travelled around the country. The shot of a politician with a doorway ‘exit’ sign above their head is a classic example of this genre, with the sign meant to be read as an indictment of their electoral chances.

Howard also gave a speech in front of a poster that read, ‘Cheaper diesel means cheaper goods’. Meares positioned himself so that only one key part of the sign was visible above Howard’s head (see below). The image ran on the front page of the Newcastle Herald. These types of photographs led political parties to employ ‘advancers’, young staffers in campaign teams who scout out locations and scope venues in order to remove or cover over any items that could be visually damaging. But even with advancers, there are still occasional failures of visual awareness. Tony Abbott fell victim to a similar cheeky camera angle in 2015 when he visited the Reject Shop, and Fairfax’s Alex Ellinghausen captured him on an angle where the words ‘The Reject’ loomed above Abbott’s head. Gillard was photographed with a freeway ‘exit’ sign behind her, and Rudd with photographs of Nazis behind him in a school-room history display.

6.8 John Howard stands in front of a billboard on the cheaper diesel fuel truck. The full text read, ‘Cheaper diesel means cheaper goods’, 4 September 1998. Photographer Andrew Meares, published in the Newcastle Herald (Andrew Meares/Fairfax Syndication).

Graham observes that political photography is ‘a fairly unique area’ of press photography because ‘with politicians, you’re going for the throat … they’re in the eye of the story and [of] a time, and you’re going for something very of that time’. Meares argues that ‘the skill set’ for political photography requires ‘being quick like a sports photographer but … intelligent to know the background story … Unlike doing sport, which is often repetitive … with politics it often only happens once.’ Context is crucial. Graham notes that a photographer has to ‘have the background’ to know which image will work. This means political photographers ‘look for images that fit the narrative of the moment’, so if the story is about the prime minister’s approval ratings going down, photographers are ‘looking for any image that portrays [the prime minister] looking weak or troubled’. Porritt also observes that as a political photographer, ‘You need to know what’s going on. You need to know who is doing what, who could possibly do what, who’s after somebody’s job.’

All of these factors give political photography what both Graham and Meares describe as a cartoon element. Graham thinks ‘politicians are sort of such unique animals … [that] photographing politicians, it almost becomes impossible not for it to be … cartoonish … [because] you try and condense all sorts of aspects of a story into one image’. Meares agrees that press photographers who specialise in politics are ‘political cartoonists, in a way. We’re often trying to pick pictures that are a little bit provocative … There’s an ambiguity that we’re playing with … either confirming prejudices … or trying to challenge them by an image in a different context.’ Political photographers are also ‘accentuating mannerisms, in a way a cartoonist uses caricature to overemphasise certain features’. Finding opportunities to accentuate features is particularly important when photographing in settings that are visually dull or repetitive.

Photographers who work at Parliament House in Canberra work in a very controlled environment with many rules. Only members of the Federal Parliamentary Press Gallery or Auspic (the official government photographic service) whose names are registered prior to parliamentary sittings can take photographs of members of parliament in the House of Representatives and the Senate. Press photographers’ access is granted through parliamentary officials and can be withdrawn by those officials for any breach of the rules that media organisations have to adhere to for photographs taken inside the building.

Those rules can be a source of great frustration for photographers because they act as a form of visual censorship. If a protestor jumps from the public gallery into the chamber, for example, that would potentially be very newsworthy, but the rules forbid photographs of ‘disturbances by visitors or any other persons, or unparliamentary behaviour’.21 Photographers also cannot photograph members of parliament any closer than ‘head and shoulders’ distance. They cannot use telephoto lenses ‘to inspect or take photographs of Members’ documents or computer screens’.22 There are restrictions about photographing in corridors at Parliament House, and a colour-coded map outlines where photographs can be taken. The rules are enforced by the Usher of the Black Rod in the Senate and by the Serjeant-at-Arms in the House of Representatives.

Although the rules restrict what photographers can show, they also limit the supply of photographs to those taken by sanctioned press photographers. In an era when photographs are increasingly being supplied to the media by the public—from iPhones and other camera devices—only press gallery members who have a valid pass can photograph in the chambers. Visitors to parliament, such as those sitting in the public gallery, are not allowed to take any camera devices into the chamber.

In the House of Representatives, the sanctioned press photographers can take a picture of anyone in the chamber at any time, but the rules in the Senate are more restrictive. In the Senate, only the senator who is on their feet and speaking (who has ‘the call’) can be the focus of photographs.23 One photographer comments that ‘They’re very precious in the Senate,’ and it comes back to them not wanting to be photographed doing something embarrassing like ‘falling asleep, nodding, yawning, picking their nose, or eating their earwax’. In July 2014, the President of the Senate sought to reform the Senate photography rules to make them consistent with the rules in the House of Representatives. But as Meares notes, ‘the long-awaited motion was quietly shelved’ four months later ‘without explanation’.24

Porritt recalls similar attempts when Bob Brown ‘was a senator [and] he put up a motion [proposing] that photographers could go into the Senate at any time for pictures and shoot anyone, whether they got [sic] the floor or not’. Only the first part was adopted. One experienced political photographer says, ‘It’s very frustrating for someone who … [has] an artistic eye; it’s very hard for us not to take a picture when we see it’s there. [The people who run the Senate] can hear us [take photos] … all of us [the photographers] are always in trouble.’

Breaking the rules around photography can have severe consequences. A photographer was banned from Parliament House for three days in 2014 for an alleged breach of the Senate photography rules. He seems to have been the first photographer to be kicked out for about two decades. But it is not only the individual photographer who can be denied access to the gallery; their employer’s access—for the whole newspaper—could also be withdrawn. Porritt says, ‘The big threat is that they could, if they wanted to, ban the whole bureau.’ A particular source of frustration for photographers is the treatment of different media. While they cannot photograph a senator unless that senator has the call, ‘there are six TV cameras in there’ filming them all the time. At public hearings, the photographers ‘have to ask permission before they press the button … [while] the TV guys walk in … hit go [and are ignored] because there’s no “click, click, click, click”’. Another source of frustration is that officials ‘keep changing the rules to suit themselves … so we’ve got no idea where it is we actually stand’.

While photographers have not, to date, been able to achieve a relaxation of the Senate rules, over time they have won some important battles to increase access. In the Old Parliament House, photographs used to be taken on the front steps because no photographs were allowed inside. The famous footage and photographs of Gough Whitlam after the dismissal were taken on the front steps for this reason. It was only from the 1990s that still photography was permitted in Parliament during question time, but there were restrictions around who could be photographed. This created equity issues and, when only the leaders of the government and Opposition could be photographed, accentuated the two-party system. It was only in 2010 that photographers were given access to the press gallery to take photographs, which meant they could then photograph the crossbenchers.

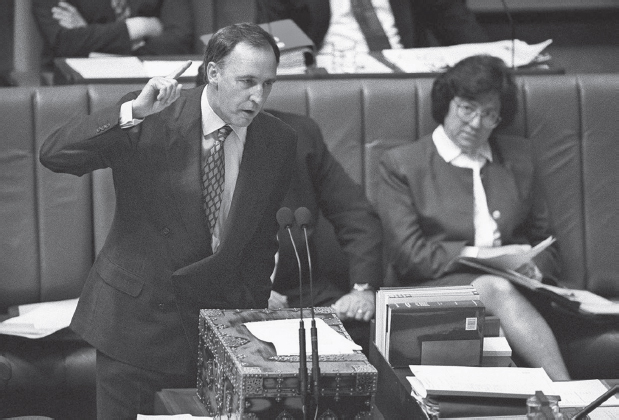

Aside from the rules, Parliament House can be challenging for photographers for other reasons. News Corporation’s Gary Ramage says, ‘We’re always trying to find new angles and new pictures because we photograph the same politicians every day.’25 Porritt also notes that it ‘can be quite boring’ because ‘you end up doing the same picture, of the same people, doing the same things, in the same place’. But he has also found ways around this, including learning the different quirks and expressions of politicians. ‘Tony Abbott has this winking habit and tongue [movement]’; Peter Costello ‘was always very animated [and] was one of the better people to take pictures of’. Porritt suspects Costello was animated ‘deliberately … just so he could hear all the shutters going off at the same time [because] there’s conditioning going on: the politicians learning what the press wants to take photos of and vice versa’. Alex Ellinghausen writes about how leaders have a ‘“thing” that makes them familiar’, including Rudd’s hair flick, Gillard’s ‘rapturous laugh’, Abbott’s wink and Bill Shorten’s deep frown when concentrating.26 Keating was an animated and combative parliamentary debater who was often captured in the chamber gesticulating in ways that captured the verbal confrontation of question time.

6.9 Paul Keating during question time in the House of Representatives, 16 October 1995. Photographer Lyndon Mechielsen (Lyndon Mechielsen/Newspix).

Inside the regulated spaces of Parliament House, politicians and photographers both find ways to achieve their goals. One photographer notes that ‘As soon as somebody says “no” to me … [it makes me] go that much harder … If we can’t photograph the senators in the Australian people’s chamber … we’ll go after them another way.’ Photographers report that politicians will deliberately enter the building by a particular entrance if they want to be photographed, or will use another entrance if they do not. The geography of Parliament House means politicians can come through the underground car park and enter without being seen, but sometimes, when they want to be visible, they choose instead to come in through the front entrance, allowing photographers to photograph them, and sometimes they stop to speak to reporters at a seemingly impromptu ‘doorstop’ interview.

It is always challenging trying to take an original photograph of politicians because they are people who have been photographed a lot. The more formal press conferences at Parliament House are key photographic events, but Porritt says they can be challenging because the background at the main ministerial press conference room at Parliament House ‘is so boring it’s not funny’, which means the photographer has to concentrate on the facial expressions of the speaker ‘or when they get animated’. In 2015, Abbott’s office attempted to provide a more interesting, and patriotic, background with an abundance of flags.

6.10 Tony Abbott and ministers, Parliament House, Canberra. Photographer Mike Bowers, published in the Guardian (online), 25 June 2015 (Mike Bowers/Guardian News & Media Ltd).

Australian photographers have enjoyed comparatively good access to national leaders compared with press photographers in many other countries. However, Australian politicians have recently been making moves towards a more American-style approach of controlling political imagery through pool photography and supplied photography. US press photographers have to comply with very strict White House restrictions on access to the President and on taking photographs. Events may be restricted to an official photographer employed by the White House, rather than being opened up to a press pack. Pool photography is prevalent. For example, in 2011, US newspapers agreed to have only one still photographer present at live presidential broadcasts, who then had to make their photographs available to all media.27

During the 2013 election, Kevin Rudd sometimes invited one photographer on his plane to accompany him at events, and that photographer was then required to share their images with other organisations. The well-known photograph of Rudd and Gillard in 2010, examining electorate maps but failing to make eye contact, was their first public meeting since she ousted him from the prime minister’s office six weeks’ earlier, and it was staged to challenge perceptions of their acrimonious relationship. It was also a pool photograph. Only one photographer was allowed in at the start of the meeting.28 In that case, restricting access may have been counterproductive because the homogenous view of a single camera reproduced across many outlets seemed to magnify the importance of that awkward interaction.

The British Prime Minister, David Cameron, had a personal photographer and filmmaker when he was in Opposition. They were controversially appointed to civil service roles after he was elected and then, after criticism, taken off the public payroll and re-employed by the Conservative Party.29 The Obama administration has been described as one of the most visually controlling administrations. It drew the ire of journalists in 2013 for its tendency to ‘self-publish’ and for ‘limiting press access in ways that past administrations wouldn’t have dared’.30 One of the areas of complaint related to the administration’s employment of Pete Souza as Obama’s photographer and the widespread reproduction of Souza’s images in many outlets, including Time magazine. The National Press Photographers Association criticised the White House for ‘pushing out its own White House photographs’ on its website ‘rather than allowing news organizations independent access to the President’.31 The shift towards political leaders preferring to circulate their own press release–style pictures taken by their own paid photographers was replicated in Australia in 2015 when Abbott hired News Corporation photographer Brad Hunter, raising concerns that press photographers might be denied direct access to the prime minister in lieu of supplied images.32 These moves led to concerns about decreased opportunities for independent press scrutiny.

Compared with other areas of press photography, political photography remains formal, official and journalism-centred. Press photographers are powerful because their photographs can boost or damage a leader’s political fortunes and a party’s electoral chances. But photographers are also vulnerable to the ever-present threat of losing access to their subjects. If they can’t take photos, they can’t work. Access can be denied because of breaches of frequently changing rules, but also because powerful politicians may prefer to give another outlet’s photographer more privileged access, or might deny a photographer opportunities as revenge for an unflattering image.

In a digital era, many images can be taken with a single camera, the space and page limits of printed newspapers are transcended online, and a 24-hour news cycle has led to a greater demand for content. In this environment, politicians are vulnerable because they are trying to provide a stream of suitable images in an era where they are far more regularly filmed and photographed than in the past. Even photographers are occasionally surprised at what a leader will do to deliver a photographable moment. Presumably, Abbott eating a raw onion at a Tasmanian produce farm in 2015 may have been motivated by the desire to create a visually interesting image.

Photographers and politicians both want visuals that tell a story and resonate with news audiences, even if the stories they each want to tell are often different. The two groups have a working relationship that is dynamic and marked by a mix of conflict and cooperation, monitoring, reaction and adaption, and formal and informal rules. Sometimes, politicians and photographers work together to achieve a result that is mutually advantageous in communicating a story. At other times, they try to circumscribe each other’s advantages.