SALLY YOUNG

TO UNDERSTAND PRESS photography, we cannot think only about the content of press photographs; we also need to think about what is not shown, what has occurred outside the frame and beyond the viewer’s sight. This includes how a photograph has been arranged and selected, but also how it is contextualised on a page or screen, including how it is explained and given meaning through placement, headings, captions, text and the use of other photographs. For the majority of photographers, and especially those who are not picture editors, many of these factors are beyond their control most of the time, and the final presentation of their photographs is heavily influenced by the work and motives of others, including picture editors, editors, journalists, newspaper managers and owners.

This chapter highlights how newspapers are powerful political actors in their own right. It has been well documented that newspapers are not detached, neutral arbiters of issues, even if they have traditionally promoted themselves that way. Newspapers have various political, commercial and policy interests. They often form and express an editorial stance on issues such as taxation, industrial relations, criminal law, social policy or asylum seekers. Sometimes, they advocate for or against a political party, leader or policy proposal. Some newspaper publishers, and some specific newspapers, have been more politically strident and campaigning than others. This is not fixed—the strength of a newspaper’s activism, as well as its position on issues, can vary over time.

To talk about ‘a newspaper’ in terms of its preferences is somewhat confusing because a newspaper is an inanimate object. When we talk about a ‘newspaper’ in this way, the term is used as shorthand for the editorial position of a newspaper as established, usually, by the newspaper’s owners and executives, and reflected in the content produced by its staff. In Australia, newspaper power has traditionally been considered to be unusually strong by international standards. Two factors that have contributed to this are the high concentration of newspaper ownership and the often close relationships between senior politicians and powerful newspaper owners, including Keith Murdoch, Rupert Murdoch, Warwick Fairfax, Frank Packer, Kerry Packer and Kerry Stokes.

Newspapers are sometimes open about their attempts to influence politics. For example, the Sun News-Pictorial ran a campaign in 1970 calling on politicians to introduce laws for compulsory seatbelts. At other times, newspapers are coy about the extent to which their reporting stems from a predetermined stance or is deliberately aimed at influencing a political outcome. Newspapers developed out of a history of ‘yellow’ (partisan) journalism and a tradition of press barons using their outlets to try to influence political debate, but in the mid to late nineteenth-century, newspapers began to promote the ideal of impartial journalism as a way of responding to changes in politics and society, attracting larger audiences and cementing journalism as a valued civic service.1 Newspapers moved away from relying upon a small number of political sympathisers paying high subscription fees. Instead, the economic model that propelled newspapers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries depended upon circulation and advertising revenues, which meant attracting a wide audience of many people paying a cheap price for the newspaper.2 In the 2010s, we have seen this economic model reverse, as mass advertising declines and subscription fees return in the form of online ‘paywalls’.

Despite their promotion of objectivity over partisan journalism, newspapers are not actually bound to be impartial in their presentation of political news, unlike television broadcasters—which have to adhere to licence conditions about objectivity. Newspapers are free to express strong views and opinions and to favour particular politicians or parties. The Australian Press Council states that a newspaper ‘has a right to take sides on any issue’.3 In its election guidelines, it also ‘upholds the right of a newspaper … to favour the election of one party and to oppose the election of another’, but it still expects that news reports should be fair and balanced, and that fact and opinion be made clearly distinguishable.4 These different aims can be difficult to reconcile. Reflecting this, and the greater advocacy and partisan role that newspapers play, Australians have traditionally said in surveys that they view newspapers as more ‘biased’ than TV and radio.5

When a newspaper does ‘take sides’, this partisanship is expressed most clearly in the newspaper’s editorials, but it can also influence its news coverage, including the selection and presentation of photographs. When senior editors give reporting staff instructions to report news in some predetermined, partisan way, these are referred to as ‘riding instructions’.6 This does not seem to happen as often as the more conspiratorially minded would believe, and it is tempered by the professionalism of newsworkers, including their adherence to professional standards that they value. Nonetheless, there have been some famous (or infamous) examples of allegedly partisan reporting in Australia. These include Keith Murdoch and the Herald’s support of Joe Lyons in the 1930s; the 1961 federal election, when John Fairfax Ltd threw its editorial support and key staffers behind Labor’s Arthur Calwell; Frank Packer and the Daily Telegraph’s undermining of John Gorton and promotion of William McMahon for the Liberal leadership in the late 1960s and early 1970s; the 1972 election, when the Age and Rupert Murdoch’s Australian backed Gough Whitlam’s Labor; and the 1975 elections, when Rupert Murdoch’s papers turned sharply against Whitlam, leading his own journalists to go on strike to protest against distortion of their copy.

As a result of changes in ownership, Rupert Murdoch is viewed as the last remaining dynastic and ‘hands-on’ newspaper owner in Australia. Several photographers express a view that Murdoch is politically powerful. Alan Porritt, who worked for the Australian, says of Gough Whitlam that ‘Murdoch got him in [in 1972] and Murdoch got him out [in 1975]’. Porritt also says that ‘The power of newspapers then, I think, was a lot stronger than it is now because Murdoch could make or break someone quite easily, and he did.’ Several photographers also mention the Murdoch press’s role in promoting Tony Abbott in 2013. When there is a strong newspaper view on some issue and it is very evident to staff working on the newspaper, ‘riding instructions’ may not be necessary. Self-censorship has been identified by Australian newsworkers as a key influence on their work.7 Media-ownership concentration in Australia means there are very few newspaper employers to work for. Job losses, casualisation and outsourcing in the 2000s have exacerbated conformist pressures—especially in the more partisan, campaigning news-rooms. Depending upon where they have worked, photographers describe very different experiences of this in terms of political photographs and have dealt with it in different ways, which are explored in this chapter.

Newspapers have sometimes been accused of deliberately using photographs in service of a political goal. This section looks at two cases, occurring seventy years apart, where that goal was alleged to have been motivated by a paper’s economic self-interest.

During World War II, John Dedman, as Minister for War Organisation of Industry in the Curtin Labor government, was responsible for reorganising non-essential industries to free up workers and resources for military needs and essential services. In late 1942, there had been talk that Dedman might demand that metropolitan newspapers reduce their resources and staff.8 Six months prior, in July 1942, Dedman had introduced a wartime restriction on clothing that restricted the sizes and styles of women’s dresses to avoid wasting material. When the rule was introduced, the Sydney Sun reported that ‘The new skirt lengths are ideal.’9 But after word spread that Dedman might rationalise newspapers, the Sun began to ridicule him over the clothing regulation.10 On 3 January 1943, the paper published two photographs. The first was of a tall woman wearing a too-short dress, and the other was of a short woman wearing a dress that was too long, down to her ankles. The paper claimed that Dedman’s rules forced women to wear such unsuitable dresses—including some women who would have to, as the headline said, ‘SHOW [their] KNEES’ because the length of their dresses had to correspond to their bust measurements. (Dedman responded that this was false and ‘ridiculous’.11)

Both of the women in the photographs later made affidavits. They said the Sun photographer gave them the dresses to put on. He then asked the tall woman to hitch her dress up while he stood six steps below her to take the photograph in order to make it look even shorter. The other woman said the bust portion of her dress was ‘padded with brown paper’ and the photographer climbed a stepladder to photograph her, making the dress appear even longer. Dedman’s department lodged an official protest, saying the women were never obliged by the regulation to wear those dresses and had never worn them except for a few minutes when the photographer directed them to. The department asked the paper to publish its letter but the paper refused. The department’s letter to the Sun editor charged him ‘with deliberately faking these photographs in order to mislead the public’, and branded the photographs ‘barefaced deception’.12

Seventy years later, Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd accused Rupert Murdoch of using his newspapers to campaign against him during the 2013 federal election. He claimed Labor’s National Broadband Network (NBN) policy of extending high-speed broadband internet into Australian homes was the reason for Murdoch’s antagonism, because it was a potential threat to News Corporation’s pay television interests through Foxtel.13 It is debated whether this was the motivation, but it was certainly apparent that Murdoch’s tabloids, especially the Daily Telegraph and Courier-Mail, supported the Abbott-led Coalition during the election in an unusual way, more like the partisan approach of a British ‘red-top’ (tabloid) newspaper.14

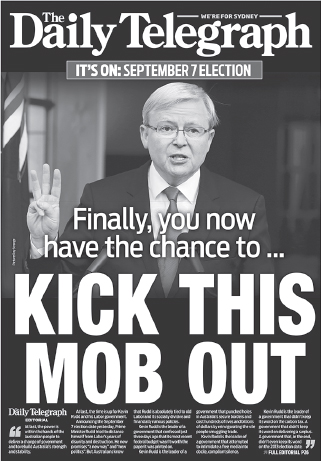

On the first day of the campaign, the Rupert Murdoch/News Corporation–owned Daily Telegraph infamously directed readers to ‘KICK THIS MOB OUT’. The headline was accompanied by a photograph showing Rudd mid-speech, mouth open, lips apart and pursed. This was an early, and still fairly mild, image. Later images were more unflattering, and photographs were repeatedly selected showing Rudd with an open mouth. This is a cross-cultural technique of ridicule, and in British politics, partisan newspapers often represent politicians they disapprove of by showing them mid-sentence, with their mouth hanging open.15

7.1 Daily Telegraph front page during the 2013 election, 5 August 2013. Photographer Ray Strange (Ray Strange/Newspix).

While digitalisation has been liberating for photographers in many respects, Peter Davis argues that it has also meant newspaper photographers have become increasingly ‘alienated’ from their work as they are less involved in how their images and stories are being represented.16 The digital editing of photographs by Murdoch tabloids during the 2013 campaign was, by Australian newspaper standards, remarkable and controversial. At one point, a photograph of Rudd’s face was edited onto a Nazi uniform to represent Rudd as a bumbling Nazi from the 1960s television program Hogan’s Heroes. Another photograph of Rudd and Peter Beattie, Labor’s ‘star candidate’ for a key marginal seat in Queensland, represented them as clowns framed by circus tents that had been photoshopped in behind them. Photographs were also altered in ways contrary to the usual tradition that news photographs bear witness and represent ‘reality’. Putting this far more bluntly, Rodney Tiffen says that the Daily Telegraph’s editors behaved ‘like a group of ageing attention-seekers who have just discovered Photoshop’.17 Photographs can be captioned, altered and represented in various ways, and photographers often do not have the final say in how their work appears, as these examples vividly show.

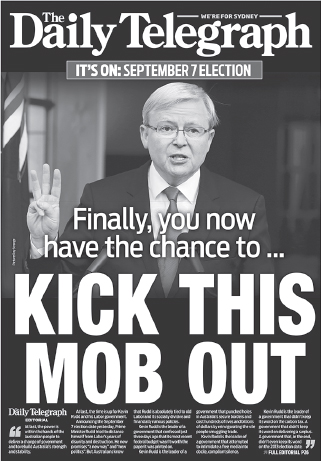

In stark contrast to the visual representations of Rudd, photographs of Tony Abbott published on News Corporation tabloid front pages during 2013 were overwhelmingly positive and noticeably presidential in nature. Several front pages showed Abbott with an Australian flag fluttering behind him. The flags appear to have been added to the photographs through digital editing. Headlines imposed over the photographs stated the newspaper’s stance unambiguously. One said that ‘AUSTRALIA NEEDS TONY’. Other similarly positive and patriotic photographs were headlined ‘TONY’S TIME’ and ‘I’M READY’. These were cases of outlets using photographs as a form of editorialising.

7.2 Sunday Telegraph front page during the 2013 election, 1 September 2013. Photographer not cited (News Corporation Australia/Newspix).

As in the Dedman case, critics alleged that the newspaper’s manipulation of images was motivated by its commercial interests. What had changed were the techniques involved. Whereas the ‘faked’ photos in 1943 required dresses, a stepladder and paper padding, in 2013 the photographer might take a standard photograph of a politician, which others then change significantly through digital editing. The Murdoch press’s unusually strong stance in 2013 was noted by many, including photographers. Neville Waller notes that Murdoch’s attempts ‘to manipulate things’ politically were far more ‘blatant’ than Packer’s had been. Verity Chambers says that although the Daily Telegraph ‘does some great reporting and certainly very good photography’, she had ‘never seen a newspaper declare its politics in the way it did before the [2013] election. They almost completely undermined their own political reporting. The photographers [and reporters] just kept on doing their jobs … But those front pages … Unfortunately, it just declares that nothing you’re going to read … [in the paper during the campaign] is going to be balanced.’

Notably, the ‘faceless men’ picture (discussed in the previous chapter), the Dedman dress images and Murdoch’s 2013 election coverage were all alleged to be cases of anti-Labor bias. While claims of newspaper bias have been made by all political parties, the Labor Party has traditionally viewed itself as the victim of what early Labor politicians tellingly called the ‘capitalist’ press. Historically, the more rancorous battles between newspaper owners and politicians have also involved Labor MPs and leaders. The election-eve editorial stances of newspapers until the 1970s and 1980s show that Labor has been the less favoured party in commercial newspaper coverage.18 But in the more polarised and partisan newspaper market of the twenty-first century, News Corporation columnists also accused their media rivals, Fairfax Media, of a pro-Labor, anti-Coalition bias.19

One does not need to accept every allegation of bias, including the ones presented in this chapter, in order to understand that photographs can—and have—been used by newspapers in an apparent attempt to achieve some political aim. The aim may be an altruistic one—publishing photographs of tragedies to spur politicians into action that protects the community, for example—or it may be to serve the political and commercial interests of newspaper owners. High political intrigue is not necessarily in the photographer’s mind as a photograph is taken. The photographer who came armed with dresses and a ladder is more likely to have been aware of how his photographs would be used for a political purpose. But for many other photographers, that isn’t the case, and their experiences of navigating political agendas within their organisations are varied.

Aside from external politics, photographers have to navigate the politics of their own organisations. Sometimes they are directly instructed by editors or management to photograph a particular politician in a favourable or unfavourable light. Guy Magowan, who worked on the West Australian newspaper, says that for the 1993 election, Paul Keating ‘wasn’t liked’ in Western Australia, but when he came, ‘you’d always try and get the best pictures of him. And I had some great stuff of him. And the editor says, “Ah we’re not using that. The bloke’s a prick.” … I’ve got good pictures of [Keating] sitting in a RAAF jet with a pilot, and they didn’t want to use it [because] they had a set against him and the government at the time.’

Magowan says editorial instructions on how to photograph particular politicians included to ‘make him look stupid’. Magowan did not like such instructions, so he ‘just took every angle and let them choose’. Magowan talks about one particular editor who ‘was a classic and would say, “I want him doing this, I want him looking like that” … [T]he pressure really came on, you know, [to] make [a politician] look stupid or … ridiculous … That pressure was on then, when he was the editor. …. We looked upon it as the dark days.’20

Porritt says that ‘Back when I was working for newspapers, especially the Australian, they could say, “Look, we want a picture of such and such in this sort of light. We don’t want a happy, smiling [photograph], [we want] grumpy or downtrodden or downcast or whatever. So, yeah, they could do that. And you do it … [W]orking for AAP, I didn’t do that because there was no point. I didn’t want to do it anyway.’ Porritt adds, ‘We went on strike about [political bias] … in ’75 … because of Murdoch; they were slanting stories. They can’t do that.’

Murdoch’s News Corporation (formerly News Limited) is viewed as a particularly political news organisation. Waller says, ‘If you were working for News Limited … there would be a certain amount of things that you wouldn’t get published if it was detrimental to whoever Rupert [Murdoch] was in favour of at that particular time … There is a bias … News Limited particularly.’ In magazines, Waller found that Frank Packer’s influence was fairly subtle: ‘You might have photographed McMahon’s children … puff pieces [but] it was probably a reasonable story on its own.’ For Waller, self-interested newspaper reporting was not just about politicians. He found proprietors were ‘pushing whatever makes them money’, including pay TV, free-to-air TV, lotteries and casinos.

One photographer who has worked for News Corporation says that no one ever told him not to take a critical picture of a favoured politician and that was not his ‘role’. He says it was up to him to capture the picture as it happened, and it was ‘for someone else to decide whether it gets published or not’. He stopped wondering why some pictures were not run and whether it had anything to do with political bias, saying it was ‘way above my pay rate’ to worry about such things. Clive Hyde, who was a photographer and picture editor at News Limited/News Corporation in Darwin for twenty-eight years, says he tried to keep himself separate from any political agenda and didn’t think he’d ever gone purposely out of his way ‘to make somebody look bad … to help out in Murdoch’s push to get rid of a government’.

Fairfax photographers also identify various influences on their work. Chambers says that over thirteen years at the SMH, she saw ‘little things once or twice where people don’t want to upset big advertisers’, but the perception of influence—that Gina Rinehart walks into Fairfax and demands favourable coverage, for example—was false. As Chambers emphasises, ‘People try to do their job as professionally as they can’, but power of various kinds can influence photographic content.

Aside from owners, politicians and advertisers, other wealthy, powerful people can influence news content. In 2014, photographer Brendan Beirne took photographs of an unedifying brawl between James Packer and his friend Channel Nine boss David Gyngell on the streets of Bondi. Demonstrating the advantages of digital, Bernie reportedly took about three hundred photographs during the three-minute fight.21 News Corporation paid out a final sum estimated to be over $200 000 for the photos, which it splashed across its newspapers around the country. But it is unlikely many other Australians who were the subject of such photographs would receive a personal visit from News Corp boss Lachlan Murdoch. Murdoch visited Packer, his long-term friend, at Packer’s apartment just as his News Corporation executives determined how the photographs would be used.22 Although Murdoch’s newspaper group had previously run a campaign against street violence and ‘king hits’ (or ‘coward punches’), which could kill, its coverage of the street brawl between two rich and powerful men included headlines such as ‘PACKER WHACKER’, and commentary that seemed to play down the violent exchange between the men as a tiff or the sort of fight brothers would have.

Hyde describes another case of influence when the Northern Territory’s Country–Liberal Party government was negotiating with developer Warren Anderson, then one of Australia’s richest men. Hyde received a tip that Anderson was on his way to the airport, so he waited there. When Hyde asked to take a photograph, Anderson told him to ‘get lost’. Hyde said he was going to take the picture anyway, and Anderson threw a punch at him. They ‘danced’ around the airport for a while, knocking over chairs. Hyde managed to get some photographs of Anderson, but when he got back to the office, a senior executive said, ‘“I’ve just had Warren Anderson on the phone … and those photographs are not to be published anywhere whatsoever and I want them here in my office.” [Hyde] said, “You’re not getting them.” And he said, “I’m the boss. I want them.” So I said, “You’re going to have to sack me because you’re not getting them.” He said, “I’ve known you for a long while; put them in your bottom drawer and leave them there.” I said, “I don’t understand,” and he said, “… [T]his bloke is a big wheeler and dealer …” I said, “That’s a load of bullshit. The whole bloody country wants a picture of Warren Anderson,” but nope, they still haven’t been published.’23

Sometimes censorship is about social mores rather than political or commercial concerns. John Ibbs explains how, in response to large demonstrations, the Charles Court Liberal government in Western Australia made it illegal for more than three people to gather in public without police permission. Every Saturday morning, civil libertarians would go to Forrest Place to stage demonstrations in protest. Police warned the speakers that if they didn’t leave, they would be arrested. In December 1980, a protester who was dressed up as Father Christmas refused to leave, so the police arrested him. Ibbs and his colleagues took images of police putting him in the back of the van, but their boss said he couldn’t publish photos of Father Christmas being arrested.24

While some photographers have experienced—or observed—the demands of a newspaper with an overt political agenda, others say that they have experienced a more subtle and far less direct form of influence, resulting instead from their awareness of context. Rather than taking a strong political stance, a newspaper may already have reported some event in a particular way, and because of that pre-existing narrative, photographers have a sense of what sort of images would be of interest to their paper to illustrate that narrative. As Angela Wylie says, photographers focus on ‘what the story of the day is’.

Andrew Meares observes that ‘if a politician is struggling, I will often shoot smiling pictures and concerned or stressed pictures’, and it’s the stressed pictures that tend to be used because the ‘smiling pictures don’t necessarily sit with the narrative of the time’. Chambers observes that with political photography, ‘there’s a certain atmosphere about what’s happening … [and] reading the mood … There are definitely personal interpretations.’ For example, ‘You might be looking for John Howard to look slightly smaller in stature, or you might be looking for Keating to be towering above.’ Chambers notes that ‘most photographers would say that they didn’t have an agenda, but I think, again, like any journalist, it’s that impossible nature of trying to be objective’. She points out that there are many complex factors affecting how photographs represent events, including ‘the personality of the editor, the different styles of reporters, the different political beliefs that photographers might have’.

Meares says he has never been told how to shoot at Fairfax, but he is aware that certain pictures get published, and that phone calls between the prime minister’s office and journalists and editors can shape coverage. Wylie, who spent more than twenty-five years at the Age, says she never felt editorial pressure: ‘I feel quite proud of that, and I definitely feel I have a personal independence. I’ve never felt pressured.’ Meares identifies what he views as different organisational cultures, arguing that ‘News Limited have more of a campaigning culture’, whereas ‘It’s more ad hoc at Fairfax.’ He contends that News Corporation ‘run certain agendas through access they’ve been given by the politicians or not … In a way, that’s the News [Corporation] model: “If you don’t give us access, we can threaten you and we can use our cameramen as … paparazzi or we can give you nice pictures if you let us in.”’ Meares’ interpretation of the tactics used by his employer’s rival is part of a broader debate about whether there is more editorial independence around the Fairfax model.

If more negative images are published in relation to one side of politics than the other, this is not necessarily a result of editorial instruction or newsroom culture; sometimes it might be more personal, an outcome of interactions between photographers and individual politicians. It can be about accessibility and relationships. One photographer admits that while he tries ‘not to play sides, as far as possible … there are some times when I’ve taken pictures of [politicians] and I either don’t like him or whatever and I’ll take a picture of him in the worst possible light that I possibly can and send it up. Whereas if I like them, I probably won’t do that.’

Negative photos (or a lack of photographs) can also result simply because a politician does not like being photographed. During his first period as prime minister, Robert Menzies is said to have avoided photographers. CJ Lloyd recounts how, during a visit to a Sydney dockyard in January 1940, ‘Menzies turned his back or put his hands over his face whenever a cameraman [sic] tried to photograph him’ and ‘walked away as soon as the cameras appeared’. Menzies later grew more accommodating with the media.25 Several photographers describe Keating as difficult or ‘incredibly negative’, whereas many describe John Howard as being ‘very obliging’ and ‘respectful’.

Waller notes that ‘Everyone’s got some sort of nice quality and you’re trying to get that out, [so] if someone rubs you up the wrong way, you can get a slightly worse picture.’ Photographers have to navigate through personal interactions. One photographer says he never makes friends with politicians, while another says he tries to remain an ‘outsider’ rather than an ‘insider’. Several photographers say they always try to keep personal attitudes separate from how they are photographing someone, and Meares says that to achieve fairness, he has a rule of being ‘equally cruel to all’. Mike Bowers admits that it can be difficult for a photographer to suspend their dislike for a politician. He says he tries hard to make sure it doesn’t ‘taint what I do, photographically. But I find it hard to divorce it, and anyone that tells you differently is lying to you.’

Sometimes more negative photos might emerge because of the party apparatus more broadly, including other MPs and party staffers. Waller has found that politicians who don’t know ‘how to handle the media properly’ or don’t have ‘a good press secretary’ can suffer because ‘you’ve got to feed the media correctly; if you start sort of being difficult, it comes back to bite you’. There can also be an element of self-fulfilling prophecy if party officials are uncooperative because they feel newspapers have been unfair or overly critical. This might help explain why several photographers suggest that Labor politicians tend to be more defensive. According to Andrew Chapman, ‘The Liberals have always been very open about being photographed and very gracious … [while] the Labor Party tend to be more paranoid and secretive.’ Porritt has also found Coalition members easier to get along with: ‘[I]t was so obvious. [Labor members] didn’t want to know you … There were a few [Labor] senators early on when Whitlam was in Opposition who wouldn’t even look at you. But the Coalition politicians would have a laugh with you.’ Porritt found it very strange that ‘the Labor people didn’t see the power of images to help them [or] … realise that a picture could either make ’em or break ’em’.

Photographers’ work is based upon their knowledge of newsroom culture and newsgathering processes. Successful photographers are successful because they so adeptly anticipate what their news organisation wants and needs. This could be something that fits with their employer’s and/or editor’s stance on an issue, or just something that fits the story of the moment (and these two things may be difficult to untangle). But at other times, the meaning ascribed to a particular image can be defined by contextual matters beyond the photographer’s control. One photographer recalls being completely surprised by other journalists’ interpretation of an image he took of a politician and was angry at himself for not anticipating that reaction. Photographs can be used in a selective way as part of the political agenda of a newspaper, or to present a slanted version of events. When this happens, some photographers deliberately separate how they do their job from how their work is used by their employer. Others report that they have more say in the selection and editing processes. And some note that their ultimate means of control over their own work is their ability to withhold particular photographs and not submit them to editors.

Most of the time, the ethical dimensions of political photography are not visible to the audience. They are determined when individual photographers make decisions about what to photograph and which photographs to submit to their editors, or when decisions are made collectively within newsrooms. But sometimes, controversial decisions about editing photographs spill out into the public domain. Given how easy it is to manipulate digital photographs, allegations of that occurring in Australian political photographs are noticeably rare, but there have been some examples of manipulation, and two of the most prominent instances occurred before photoshopping was even possible.

In December 1940, after three months of the Blitz, with German bombs still hitting London, the Hobart Mercury published a front-page article on 5 December, criticising Australian federal politicians for their absence from parliament the day before, when ‘the Empire is fighting grimly for existence’. As a contrast, the Mercury placed a photograph of the destruction in London above a photograph of a nearly empty House of Representatives, which showed only one member in his seat. But this photograph had been altered. It had been taken sixteen days earlier, on the day parliament assembled, when it was nearly full, but the Mercury had manually erased all MPs except one to make a point about MPs missing parliament because they were at dinner. Menzies was outraged and described the ‘fake’ photograph as a ‘public scandal’.26

In 1976, a press gallery photographer’s accreditation was withdrawn for two weeks after he photographed the then leader of the Opposition, Gough Whitlam, in his office. The resulting photograph, taken by News Limited photographer Maurice Wilmott, had been taken without permission, but it was also altered by others when published. In the original photograph, Whitlam’s personal secretary was shown behind him. In the version published in the Daily Telegraph, Whitlam’s secretary had been painted out and the caption described Whitlam as a ‘lonely figure in the Federal caucus room’. Like Menzies thirty-six years earlier, Whitlam was outraged by the ethical breach.27

It is interesting that both of these examples are parliamentary photographs, because in Parliament, as noted previously, written rules circumscribe photographs of parliamentarians. By contrast, when it comes to politicians’ private lives, social conventions and journalistic culture circumscribe the boundaries. Compared to British newspapers, Australian media have tended to be comparatively discrete about politicians’ private lives. The British paparazzi-style of political photography is not common in Australian newspapers, and allegations of longstanding extramarital affairs conducted by Australian prime ministers have not been reported during their tenure.28 There have been exceptions to this discrete approach to politicians’ private lives, but such examples tend to be rare and controversial.29 Australian photographers are restrained by their own sense of what is acceptable in terms of privacy and the public interest, as well as the conventions of their newsrooms and journalism in Australia more broadly. Two incidents have helped define those limits in relation to photography.

In February 1975, Deputy Prime Minister and Treasurer Jim Cairns’ relationship with his staffer Junie Morosi had been the subject of intense interest and speculation. Cairns had responded to a hostile reporter’s questioning by saying that he had ‘a kind of love’ for Morosi. Alan Reid argues that the publicity around Morosi was especially ‘pictorial’ because she presented press photographers with a very ‘photogenic subject’.30 During the ALP’s National Conference, a photographer hid in a tree and waited while Morosi, her husband, Cairns and his wife all had breakfast on a balcony. The photographer took a photo just when Cairns’ wife left the balcony, and with Morosi’s husband out of shot. The Daily Telegraph published the photograph showing only Cairns and Morosi the next day, with the headline ‘BREAKFAST WITH JUNIE’.31

Another incident in 1997 was also controversial. Senator Bob Woods had been in the news both for his extramarital relationship with a woman who was a Liberal Party worker and as the target of an investigation by the Federal Police into allegations he had rorted his parliamentary expenses. After the revelations of his infidelity, he returned to the family home and was photographed having an emotional private discussion with his wife Jane in their backyard. Photographs were published by the Daily Telegraph. The photographer had reportedly obtained them by waiting for hours at a distance with a powerful long-range lens trained on the couple’s backyard. In an unusually strident condemnation, the Australian Press Council described the photos ‘as a blatant example of the unjustified breach of privacy’. Calling them ‘sneak photographs’, it said it did not see any ‘compelling public interest in the obtaining and publication of pictures of this kind’.32

Newspapers make decisions behind the scenes about what is reasonable, where the limits of privacy are situated and what is in the ‘public interest’. Despite claims that our era has seen the end of privacy, it appears there still are some limits. In 2014, the Northern Territory News suggested that it had private emails containing a nude photograph of a female politician—taken three years before she entered politics—but it did not publish the photograph.33 On another occasion, when a newspaper did publish nude photographs of a female politician, it was the victim of manipulation rather than the perpetrator. In March 2009, the Sunday Telegraph published what they promoted as ‘nude photos of [One Nation politician] Pauline Hanson’, only to find out soon afterwards that the photographs were of someone else. Hanson later received an undisclosed settlement and a brief apology on page two of the paper.34

Privately taken photographs have been increasingly used in other types of news reporting—such as for victims of crime—and are more regularly finding their way into political photography as politicians increasingly use social media and post private photographs of themselves and their families. In 2014, questions were raised around ethics, privacy and consent when the Australian published a photograph of Greens senator Larissa Waters’ six-year-old daughter wearing a princess costume to criticise Waters for hypocrisy over her stance against the gendered marketing of toys. The photo was taken from Waters’ Facebook site without permission and published with the girl’s face blacked out.35

Some politicians have been remarkably indiscreet in the face of the possibility that images they consider to be private, and have transmitted through email or text messaging, could be published. In 2013, News Corporation’s Courier-Mail reported that Queensland Liberal National party MP Peter Dowling had sent a woman photographs of himself naked, including a photograph of his penis in a glass of red wine. On its website, the Courier-Mail published several photographs of ‘Peter Dowling and his mistress pictured on holiday abroad’ and also showed a montage of the more explicit photographs with a red ‘CENSORED’ banner covering the most explicit parts.36

Some online sites, such as political blogs and celebrity gossip websites, which profit from hits to their content and are unconcerned by traditional journalistic ethics, are pushing the boundaries. US politician Anthony Weiner’s sexting (sending explicit sexual material by mobile phone) was revealed by website The Dirty and a conservative blogger. Major newspapers then published the revelations—mostly by describing the more explicit photos. The New York Post showed Weiner’s bare chest on its front page. Visual images are of historical importance to tabloids especially, and tabloids have been the outlets that have tended to push the boundaries of ethics in political photography in Australia. But tabloids face intense competition online as sites post more sensational and explicit images, such as the website headline promising ‘ANTHONY WEINER’S UNCENSORED PENIS PICTURE PLUS 10 OTHER IMAGES THAT ARE EVEN MORE OBSCENE’.37

Politicians have also been caught out by mobile phones used by others to record their behaviour. In December 2015, the Herald Sun published a video clip online, and stills from the video in its printed paper, that they said had been sent in by a concerned ‘witness’ who had used their mobile phone. The video showed Labor leader Bill Shorten appearing to be texting on his phone as he drove along a busy street.38 Politicians have also been the source of mobile phone photographs leaked to newspapers. In early 2016, junior minister Jamie Briggs resigned following complaints by a female public servant of harassment in a Hong Kong bar. A pixelated photograph of the 26-year-old woman was published on the front page of the Weekend Australian. Briggs admitted the photo came from his own mobile phone but denied leaking it to the newspaper, saying he had ‘sent it to a few people’.39 The leak was widely condemned as a breach of her privacy.

In democracies, peaceful protest and dissent are considered to be both an expression of free speech and an important way in which members of the public communicate their dissatisfaction to political leaders. But the visual images of protest and dissent published by newspapers represent events in very different ways depending upon whether the cause and conduct of the protest are supported by the newspaper and public opinion.

As previously discussed, representations of anti-Vietnam war protests varied and shifted over time as popular support for the anti-war movement increased. But in another area of protest, newspaper hostility has been far more consistent. Keith Windschuttle found in 1988 that the way newspapers report industrial dissent, unions and strikes ‘has been remarkably consistent and predictable: unions are ruining the economy and strikes are always bad news’.40 Henry Mayer also found a long-established pattern of newspaper reporting since the early 1900s. Mayer argues that the editorial position of newspapers on strikes ‘consist[s] of two, and only two, points: first, the union claims will ruin the economy, and even if seen as just, the time is not good now; second, even where a right to strike is granted, the [strikers] always act “irresponsibly”’.41

This pattern of reporting has happened, Mayer argues, not because of some conspiracy or deliberate policy but simply because reporters have been unable to ‘even begin to grasp what goes on in the mind of factory-workers’—a perspective ‘possibly shared by most middle-class people’.42 This is an interesting point because, even when Mayer wrote his analysis in 1968, newsworkers had been involved in strikes for over a hundred years. Many of the earlier strikes centred on the more working-class printers, but later strikes involved middle-class journalists and, indeed, photographers who battled for pay parity.

Even if we grant newsworkers a better understanding of the desire for improved industrial conditions than Mayer does, we should also note that newsworkers’ employers—the target of their strikes—are less likely to be supportive of industrial action. Media companies are large employers, and industrial relations are a major issue for them. More so than many other political issues, the presentation of strikes is unlikely to be neutral.

In 2005, the Howard government made changes to federal industrial relations laws through its ‘WorkChoices’ legislation. It argued the changes were about creating more flexible, modern workplaces, while opponents—particularly unions and the ALP—argued they were about stripping conditions from workers. Newspapers had strong views on the issue. The Australian acknowledged in 2007 that ‘We have always supported the [Howard] Government’s IR policy.’ The Herald Sun argued that it was a considerable achievement, and the Daily Telegraph said, ‘People are better off now.’ At Fairfax, the SMH argued similarly that ‘we believe WorkChoices was the right policy, a necessary reform’. The AFR, with its business audience, was also supportive.43 In the Latham Diaries, former Labor leader Mark Latham recalls a dinner he had with News Limited executives, including Lachlan Murdoch, before the 2004 election. Latham claims that they ‘pressed hard for me to drop [Labor’s] policy dedicated to [the] abolition of [WorkChoices], but I told him there was no chance of that’.44

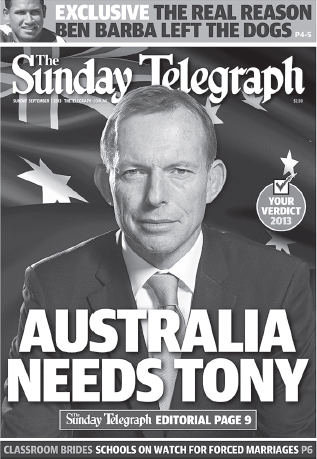

The Herald Sun’s coverage of one anti-WorkChoices rally left the reader in no doubt about how to interpret the photographs. Reflecting one photographer’s observation that newspapers ‘put protests they don’t agree with on latter pages of the newspaper’, this event—part of a national day of action—was shown on pages four and five of the Herald Sun (the front page was about cricketer Shane Warne’s marriage break-up). Aerial shots showing large numbers of people attending a protest can further protesters’ campaigns by showing how much popular support exists for their cause, and this page included such photographs. But it also showed several close-up photographs. On the right, two photographs showed protesters with clenched fists gesticulating, and the smaller photographer showed a bald man in a CFMEU T-shirt with a clenched fist. The open-mouthed shouting denoted anger, and the headline also framed the interpretation of the photos as a ‘FIGHT’ and ‘Industrial Anger’. The word ‘fury’ was also visible, and in the photo captions, readers were directed to note the ‘clenched fists’, ‘anger’, ‘raw nerves’ and ‘chants’. The caption ‘workers show their solidarity’ suggested Marxism. At an event of this kind, and especially in the digital era, many photographs would have been taken. It is fascinating that those that were chosen so closely mirror what many previous studies of strike coverage—both in Australia and elsewhere—would predict.45 The article and photographs positioned the strike as chaotic, disruptive and threatening.

In the British context, Anders Hansen and his colleagues note the prominence accorded to bald protesters in newspaper photographs. They argue that a ‘wider “mythic” view of society [has been] established in past reporting of conflict situations in which organised groups of politically motivated extremists, anarchists and general “trouble makers” are said to travel the country in pursuit of violent confrontation’. This is the ‘rent a mob’ or ‘rent a crowd’ who ‘are motivated by less than political ideals’.46 Chief among the visual representations of them is the bald, angry protester who visually suggests that a ‘militant minority’ is to blame for the strike.47 Hansen and colleagues discuss a British newspaper photograph of a bald protester: ‘With no head hair he readily becomes assimilable to a public perception of skinheads—a group widely identified with anti-social behaviour and thoughtless violence … Mouth open, he appears to be shouting in anger, a further form of public behaviour often associated with “yobbish” activity.’

7.3 Page 5 of the Herald Sun, 1 July 2005. Photographers Craig Borrow and David Caird (Craig Borrow/David Caird/Newspix).

The image sets up powerful connotations of ‘“them” versus “us”; “order versus disorder” … and “civilised norms” versus “deviant behaviour”’. When protesters are shown in conflict with police, this adds another dimension of ‘“legitimate force” versus “illegitimate violence”’.48

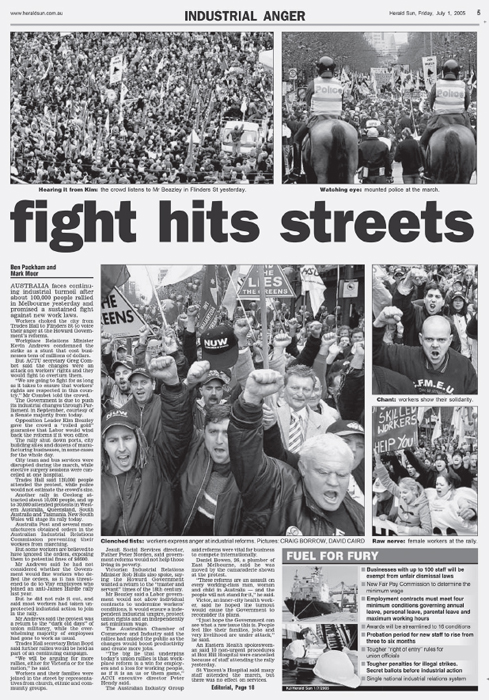

The bald protester is another cross-cultural motif. It was also a visual theme in photograph selections for the Herald Sun’s coverage of a series of protests against meetings of the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Melbourne from 11 to 13 September 2000. Those protests were part of a broader anti-globalisation movement concerned about poverty, foreign debt and the environmental impact of globalisation. The Herald Sun, part of a large multinational corporation, had already stated its opposition to the protests and argued that the WEF was an ‘open door to prosperity’, and that foreign investment and free trade were a ‘poverty buster’.49 The Melbourne 2000 protests were closely modelled after the World Trade Organization (WTO) protests in Seattle in 1999, which had been organised as an ‘image event’.50 The Australian protest organisers also tried to create a carnival atmosphere with costumes, large puppets and dragons, music and large banners. Eyewitness photographs of the events highlight some of those theatrical and visual elements.51 But the Herald Sun’s selection of photographs was remarkably similar to negative coverage of strikes and protests in other contexts and countries. In one photograph, a bald protester is prominent and framed by the headline ‘SHAMEFUL’. One veteran photographer observes that if a newspaper is against a protest, the shot selected by editors will often be of ‘the “rent a crowd” element’. In this case, the photograph selected zoomed in on a bald, militant-looking individual in the same way, and seemingly for the same effect, as the British study describes.52

Analysing photographs in the context of a newspaper’s pre-existing stance on an event, and in terms of perceptions about its corporate and political interests, has a long tradition in studies of news content. This is often performed in conjunction with the analysis of how news is gathered, selected and framed. At this level, there needs to be some recognition of the view from ground level when photographers are surrounded by conflict. Violence naturally tends to stand out to them, as it does to news audiences—which is why conflict is judged to be ‘newsworthy’. Clive Mackinnon remembers an incident at an anti-apartheid protest when he saw a mob ‘belt’ a mounted police officer ‘with poster flags’, knocking him off his horse, and then one of them jabbed a broken-off stave into the horse, which he found extremely distressing to watch. Photographers face physical dangers at potentially violent or unpredictable events. They have to learn to ‘read what is happening’ and, as Ibbs says, to ‘look for trouble and see where it [is] coming from’.

Kari Andén-Papadopoulos challenges the assumption that photographs ‘mainly function to support dominant news frames and elite political discourse with little or no potential for independent influence on audiences’. She argues that the famous Abu Ghraib photographs ‘were not in any simple way “spoken for” or tamed by the dominant news frames, but quite the opposite’: the photos independently came to ‘function as a critical prism’ through which US foreign policy was viewed. The ‘heretofore banned sight of American troops in the role of sadistic torturers [became] an integral part of our understanding of the Bush administration’s “war on terror”’.53 In other words, news photographs can transcend their context on a page or in a newspaper and come to have an independent life.

7.4 Front page of the Herald Sun, 12 September 2000, page 1. Photographer AP (Newspix).

A local example of this is a Walkley Award–winning photograph published in the Herald Sun in 1994. It is a reminder that newspaper photographers capture what they see, that the images they take are not always used in service of some preordained worldview, and that it is too simplistic to view a single newspaper as always visually representing protests or strikes in negative terms. Peter Ward’s image shows a policeman applying a pressure-point hold to an anti-logging protester. This bald protester is dressed respectably, his face contorted in pain as he sits peacefully, arms linked with others. The image was so powerful and aroused such sympathy for the protester that it led to police abandoning the practice. Ward said it was one of his proudest working moments.54

7.5 A police officer uses pressure-point techniques to subdue a demonstrator during a protest in East Melbourne. Photographer Peter Ward, published in the Herald Sun, 1994 (Peter Ward/Newspix).

As the visual aspects of news have been emphasised on screens in a post-television, post-internet world, protest groups have increasingly employed visual means of protest—protests as ‘spectacle’55—which seek public and media attention. Not content to be the subjects of images produced by others—including organisations they view as unsympathetic—protest groups stage events for, and even distribute photographs to, news organisations as a way of trying to influence media coverage. This supply role challenges newspapers’ control over the selection of images. Some environmental groups have been particularly focused on visually oriented protest, with the photograph judged as especially important by Greenpeace.56 Greenpeace hires freelance photographers, usually paid day rates, to take photographs, and has an archive of more than 130 000 images at its head office, which it seeks to circulate to news media.57 The Sea Shepherd Society has also gained favourable news coverage partly by supplying images to news media outlets.58 In Australia in the early 1980s, a photograph of a section of the Franklin River was used by the Wilderness Society in double-page colour advertisements in newspapers, as well as on postcards and other material.59 There were prominent news photographs of pro-wilderness demonstrators marching through Hobart in 1981 to oppose dams, and of demonstrators lined up in their rubber rafts stretched across the Gordon River as a blockade near the proposed Franklin River dam site in 1982. These contributed to publicising the issues, culminating in a political commitment by Bob Hawke that the dam would not be built.60

Newspapers sometimes have strong views on politicians, issues or events and express them quite clearly through their content—including photographs. Many other times, that might not be the case, or the paper’s views may not be so overt or direct. News narratives are not always affected by overt political bias, and there is more than one coherent viewpoint in a newspaper. In many instances, ‘context’ might be a more relevant factor than ‘bias’ or ‘editorial direction’. Photographers have an awareness of what the story of the day is, a sense of how their paper is going to cover it, and what images they need to take to go with that story. They know from past experience what is usually deemed ‘newsworthy’. They have their own ways of navigating their work in the larger context of their organisations. Photographers describe a spectrum of experiences, running from overt editorial direction, including censoring of photographs that do not fit the political agenda of their paper, through to those who say they have never encountered direction or believe it is overstated.

When talking about media power, it is difficult to avoid an emphasis on News Corporation. It owns fourteen of Australia’s twenty-one metropolitan daily and Sunday newspapers (nearly 70 per cent) and is the largest player in Australia in terms of newspaper circulation.61 Most of News Corporation’s newspapers are tabloids, the type of papers most noted for a visual and strident, campaigning reporting style. Journalists, when surveyed, tend to describe it as the most partisan newspaper employer.62 The photographers interviewed for this book tend to mention the company most in terms of politics and power. Another overrepresentation in this chapter is geographical. The three examples given of dissent all occurred in Melbourne, and the coverage of the Herald Sun, the only major tabloid in Melbourne, is prominent in that discussion. This selection bias is partly event-driven: the WorkChoices protest was largest in Melbourne, and Melbourne was also the site of the WEF, but a counter-example from the same newspaper—Ward’s image of the anti-logging protester—shows that such images can transcend their context and are not always anti-strike or anti-protest.

The missing piece of the puzzle, both in this chapter but also other studies of media power, is how audiences interpret photographs. Even if a newspaper promotes one side of politics, or a particular view on an issue, that does not necessarily mean its readers follow suit. If newspaper culture and hierarchy influence photographers’ work, so too do audience interpretations of their photos.