SALLY YOUNG

SINCE PRESS PHOTOGRAPHERS began photographing news events in the late 1880s, Australia has become a far more diverse society. Immigration has been at the core of this shift as millions of people from all over the world have made Australia their home. Immigration has also had a critical impact upon the lives of Indigenous Australians, with the arrival of British colonists in 1788 effecting vast changes upon Aboriginal culture and society. As Jane Lydon observes, narratives and images have been the main ways in which non-Indigenous Australians form ideas about Aboriginal people.1 While mainstream media reporting has been frequently criticised in academic research for perpetuating racism and stereotypes,2 Lydon notes how photographs ‘exploit[ed] and distanc[ed]’ their Indigenous subjects through a colonial lens, but were also used to ‘argue on behalf of Aboriginal people to reveal Aboriginal suffering to mainstream Australia, to demonstrate Aboriginal humanity, and to urge their treatment with respect and equality’.3

This capacity for photographs to hurt or help is also evident in the ways in which migration and refugee stories have been told visually.4 Within Australia, the presence of stereotypes in press depictions of immigrant communities and the influence on social attitudes to those communities is the subject of longstanding and ongoing debate.5 This chapter draws upon themes and events raised by photographers, and considers the role of press photography in showing the changing face of Australia over time, including the way press photographs document social life and culture, but also act as a site for political debates about national identity, racism, political and civil rights, inclusion and exclusion, integration, assimilation and reconciliation.

Journalist and former TV current affairs host Ray Martin said in 2008: ‘I’ve spent over thirty years deeply involved with Indigenous affairs. I well recall that generation of old newspaper editors and hacks—when I first started out—with the tedious, racist maxim that “Abo stories don’t sell newspapers”.’6 Today, another challenge confronts photographers and journalists who want to tell Indigenous stories, and it is also related to media economics. In 2013, Laura Tingle reflected on the depleted economic resources of newspapers and how they ‘no longer have specialists’ in areas such as Indigenous affairs, immigration, refugees or asylum seeker policy. Tingle said ‘Indigenous affairs used to be a huge story. Ten years ago there was Mabo, Wik, and now it’s just not there because there isn’t the focus. There aren’t people there who’ve got their own interest in getting those stories into the paper. It’s as brutal and basic as that.’7

Many of the photographers interviewed for this book are committed to showing Indigenous communities, and telling their stories in a more fair and positive way than has previously been the case. But the commercial imperative of newspapers and the historically favoured narratives have sometimes made that difficult. Despite these obstacles, many press photographers cite their coverage of Indigenous news as some of the most important, and memorable, stories of their careers. Bryan Charlton nominates his photographs of the royal commissions on British nuclear tests at Maralinga in 1985 and into Aboriginal deaths in custody in 1987 as among his most significant.8 Lorrie Graham’s first ‘big story’ for the National Times was on an Aboriginal land rights claim. But there are also regrets. With hindsight, Barry Baker regrets that he missed opportunities to document and ‘do more’ for the local Aboriginal communities in Western Australia.9

Visits to remote communities are also described with great affection as some of the highlights of photographers’ working lives, including by Guy Magowan and Neville Waller. Verity Chambers describes photographing remote Aboriginal communities from Cairns to Broome, and from Darwin to Alice, as some of the best time she’s ever spent. Angela Wylie says remote Aboriginal communities are probably her ‘favourite gig’. Age photographer Justin McManus explains how much he enjoyed visiting the community of Balgo in Western Australia, meeting a whole lot of great people in the community, finding out how they lived in the desert, and listening to their stories and humour. McManus also recalls a trip to Wadeye in the Northern Territory, where he spent time with the Dumoo family, who told him of their desire to live back on their homeland.

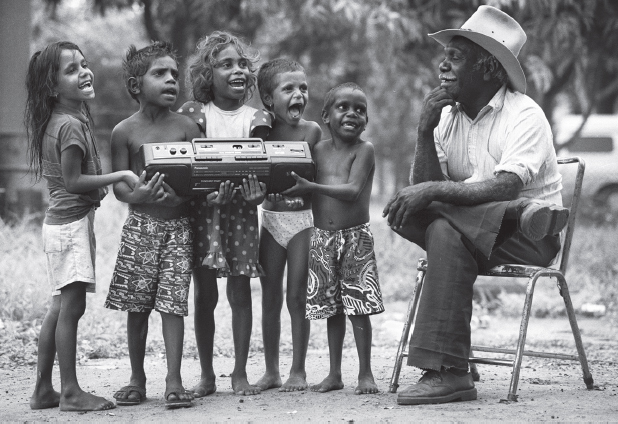

One of Baker’s most memorable photographs was taken in Kununurra in the Kimberley for the West Australian in 1993. He was covering a story on Aboriginal elders who were using the radio to communicate with younger generations, and ‘Instead of going to the radio station … which would have been a pretty bland sort of picture. [I wanted] to get one of the elders with the children … There was an Aboriginal elder sitting in a backyard on a chair with his legs crossed and a big white Stetson on his head, little Aboriginal children playing there, four-, five-, six-year-olds, seven-year-olds and a big radio blaring. I had to compose the picture with them … it just all came together perfectly.’10

8.1 66-year-old stockman George Dixon from Glenhill Station relates his story of the Dreamtime of the Barramundi on radio. Photographer Barry Baker, West Australian (Barry Baker/Westpix).

Looking at the content of newspapers over time, however, it appears that newspapers have generally not been as committed to Indigenous issues as many of their photographers have been. And that gap appears to be increasing as diminishing resources reduce newspapers’ willingness to be bold and to challenge perceptions about audience desires, as well as their capacity to send photographers to remote locations.

One newspaper that has consistently prided itself on its coverage of Indigenous affairs since its inception in 1964 is the Australian. As the only national, general news newspaper in Australia, it has more scope to move beyond regional and local-issue reporting. Clive Hyde recollects that in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Australian ran many front-page stories with his photographs on events such as the Aboriginal Barunga Festival. One photographer argues the paper remains both ‘ethical’ and ‘compassionate’ on Indigenous issues despite its ‘right-wing’ reputation. Renee Nowytarger notes how Chris Mitchell, as editor, would ‘invest a lot of money into sending a crew away [to Indigenous communities] and … doing it properly. So other news crews might leave, but we might get told to stay there for another two months.’ When Mitchell retired in 2015, after thirteen years as editor-in-chief of the Australian, Indigenous Australian lawyer, academic and land rights activist Noel Pearson described him as a ‘stalwart champion of [bringing] your fellow black Australians into the centre of national policy discussion’.11 Although there are more critical views of its coverage of Indigenous affairs, even its critics have tended to laud the Australian for the more comprehensive coverage it provides compared with other newspapers.12

For Mike Bowers, one of the crucial elements of Indigenous affairs reporting is consent. He says photographers need ‘the permission of the people to tell the story in Indigenous communities’. Bowers says that ‘when you go to those communities and especially those vulnerable ones, you have to spend a fair bit of time before you actually pull your cameras out … I think you have to get to know people … spending a couple of days [there] without pulling the cameras out and then, slowly, bring them out and start to do it. And that takes time. And what modern media organisations don’t have any more is time to … put into these things and that’s going to affect the quality of what’s around.’

In 2007, the Howard government controversially launched an Intervention in the Northern Territory. Following allegations of child sexual abuse and neglect in Northern Territory Aboriginal communities, this was a package of changes to welfare provision, law enforcement, land tenure and other measures. When Graham photographed the Intervention, she went to the community elders first to seek permission for taking photographs and was careful to ‘only document things that people [were] actually okay about documenting’. She also did a follow-up and made sure that if she had promised to deliver something to them, she did. Nowytarger also left her camera behind for the first few days ‘just to … see if they, you know, were comfortable with me being around’ and to ‘let people get to know’ her so they would trust her in documenting their lives.

McManus made it known when he started working with the Age in 2005 that he had a longstanding interest in Indigenous cultures. In February 2008, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd tabled a motion in parliament apologising to Australia’s Indigenous peoples, particularly the Stolen Generations and their families and communities, for laws and policies that had ‘inflicted profound grief, suffering and loss on these our fellow Australians’.13 To photograph the apology, McManus got in touch with the Edwards family, who had been severely affected by the policy of taking children from their parents in the 1960s. McManus met the family in Victoria in the days before the apology and then in Canberra on the day. McManus describes that day, saying it was ‘hugely affecting to see the outpouring of raw emotion … that had been built up … for decades and decades’. To photograph the Edwards family on the day, McManus knew it was crucial to have a ‘knowledge of their history and of their culture’, build up a rapport with them, ‘be respectful [and] … unobtrusive’ and ‘earn their respect and understand the enormity and weight of this occasion’.

Although some commentators have criticised the apology for being empty symbolism, McManus saw for himself that it ‘meant an enormous amount’ to the Indigenous people who were there that day. He says that while opinion writers may have said that the event didn’t mean anything, ‘It’s clear looking at those pictures and being there on the day that this was a moment of enormous significance for these people; that finally government policies that stole them away from family and culture, and subjected them to a life of heartbreak and pain, had been acknowledged. That is what those pictures document, the truth of how Indigenous people were affected by these policies.’

For McManus, Indigenous stories are ‘the stories of Australia’: ‘These are the stories that are unique to this land, to our identity as a people, [and] until we realise that, … we are lost as a nation.’ McManus feels a responsibility to highlight Indigenous issues while also telling positive stories around culture. He hopes this will go ‘some way to educating the broader community about a people and culture that is the spiritual heart of this country and is there for all Australians to embrace’.

This is especially important because, as several photographers are very aware, it is not difficult to find racist, patronising and paternalistic representations of Indigenous Australians in newspapers, especially in older newspapers, where social Darwinism infused reporting, and notions of primitivism and colonial benevolence were also highly apparent. To take just one example, in 1965 an Advertiser photograph of two Indigenous children at Snake Bay at Melville Island in the Northern Territory was captioned ‘Snake Bay children being taught how to eat in the style of the whites’. The accompanying article expressed the reporter’s hope that ‘all aborigines in time’ would have ‘enough contact [with whites] to want to lead orderly and useful lives’.14 Waller recalls how racism featured in ‘the conservative … country thing of the Weekly … when it was more country orientated, it was pretty bad’.

As Lydon notes, while images of disadvantage could be designed to inspire empathy and to appeal to a shared humanity, photographs of ‘unhygienic conditions, falling down humpies, rubbish and diseases were seen by many viewers as expressions of Aboriginal incapacity rather than a symptom of a cycle of disadvantage and lack of opportunity’.15 Assimilation policies and rhetoric, also visible in newspaper reporting of the time, positioned Indigenous Australians as ‘passive children needing to be taught and helped’.16

In light of these fraught and traditional tropes, newspaper photographers continue to face difficult choices when determining whether—and how—to document the difficult conditions apparent in some Indigenous communities. Keith Barlow photographed Evonne Goolagong in her family home in the town of Barellan, New South Wales, after she won her first Wimbledon championship in 1971. The photographs were criticised for having ‘belittled’ Goolagong by showing the poverty she grew up in. But for Barlow, ‘That wasn’t poverty; that was the scene of her success, the thing that built her career … I consider that a very good photograph to combine her success at Wimbledon with how it started at Barellan.’ Other photographers have also hoped that powerful photographs might draw public and political attention, resulting in better conditions for communities. But there is a risk attached to this because the images could also be interpreted as hurting that community or feeding racist stereotypes.

Nowytarger spent months photographing the Intervention in the Northern Territory. She photographed the poor housing conditions and hoped the images would help get the community new housing. She took a portrait of a twelve-year-old girl who had a baby and documented images of domestic violence and alcohol abuse. This was all controversial ‘but I think it’s important to tell those stories [or] … everybody ignores it’. Nowytarger ‘was very conscious of the way I would shoot stuff … I documented what it was … without changing anything. So if an adult’s giving a five-year-old a can of VB, I photographed a five-year-old drinking a can of VB … Young babies, you know, eighteen months old, sipping on Coke bottles … or kids with nappies that were [so] full of shit … [their] skin was burnt … I documented that because … I wasn’t there judging anybody, I was just documenting exactly what it was.’

Of course, Indigenous Australians have also long sought to draw attention to the problems they confront—including poor facilities but also discrimination. On 26 January 1938, the 150th anniversary of the landing of the First Fleet in Australia was marked by a celebratory parade and re-enactment of the fleet’s arrival in Sydney. Once these celebrations had concluded, Indigenous Australians began marching to the Day of Mourning Congress, a political meeting for Aboriginal people only, including many Aboriginal leaders. Members of the Aborigines Progressive Association wore formal black dress as a sign of grieving. Only four non-Indigenous people were allowed: ‘two policemen and two pressmen to write or take photos’.17 But the event was not publicised as the organisers might have hoped. At least nine newspapers mentioned the Day of Mourning protest in the days following, including the SMH and the Age, but in small stories on latter pages of the paper, and none included photographs of it.18

In the United States, civil rights movements were advancing their calls for an end to discrimination and segregation. A photograph published in 1955 was a rallying point for support. Emmett Louis Till was a fourteen-year-old African American who was brutally murdered by two white men after he allegedly whistled, or even smiled, at a white woman. Till’s mother insisted on a public funeral service with an open casket to show the world the brutality of his killing. Photographs of Till’s bloated, mutilated body in the casket, published in black-oriented magazines and newspapers, led to public outcry, rallies and intense scrutiny of the state of black civil rights in Mississippi. A few months later, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus to a white passenger, later saying she had Till in mind.19

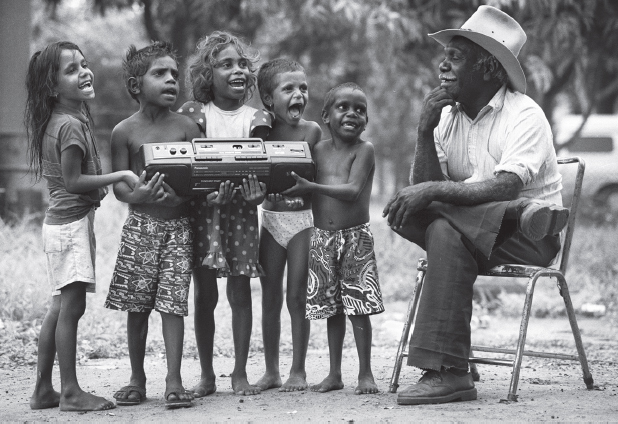

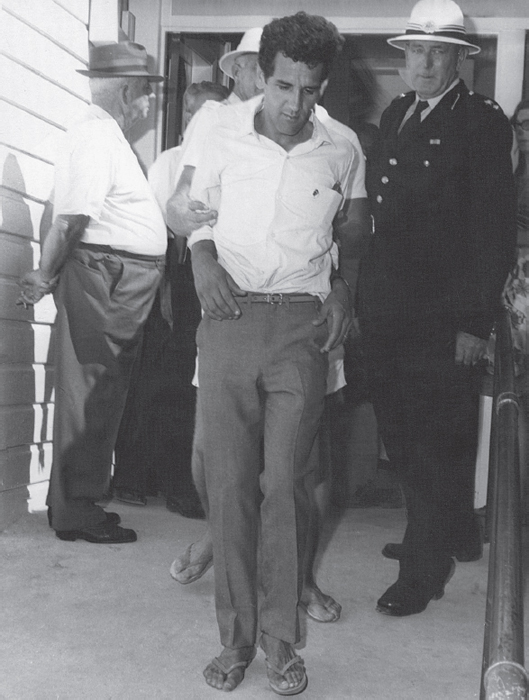

In February 1965, Charles Perkins, an Arrente and Kalkadoon man studying at the University of Sydney, led fellow students on a bus tour throughout rural New South Wales in order to highlight racial discrimination. The Freedom Ride was inspired by similar events in the south of the United States to draw attention to the civil rights movement.20 At the town of Moree, Perkins challenged a local ban on Aboriginal children swimming in the pool by taking a group of Aboriginal children there. They were escorted away by officials.21 The incident received press coverage in New South Wales and nationally, including in the Australian, where a photograph made the front page. The visuals were a key to drawing public attention to issues of discrimination and civil rights.22

8.2 The Freedom Ride, Charles Perkins taken forcibly away from Moree swimming pool. Photographer not cited, the Australian, 22 February 1965 (News Corporation Australia/Newspix).

In 1967, Australians voted overwhelmingly in a referendum for two discriminatory references in the Australian Constitution to be removed. The provisions had prevented the federal government from making laws for Aboriginal people and had excluded Aboriginal people from being counted in the census. It was a landmark moment in Indigenous rights but not an event that was represented in visual terms in newspapers. Even front-page stories tended not to include photographs.23 This may be at least partly due to the nature of the change: a Constitutional amendment following a nationwide poll does not lend itself to photographs in the way a more visually defined event might. The 1972 Tent Embassy—first a beach umbrella and then a tent pitched outside Parliament House in Canberra—was a more visual spectacle. Based upon ‘astute visual politics’, it was designed by Indigenous Australian campaigners inspired by the US Black Panthers.24 Both local and international newspapers reported on the Tent Embassy, making it a ‘major political embarrassment for the McMahon government’.25 Even so, while the Tent Embassy captured public imagination for its symbolism, wit and boldness, and contributed to policymaking and law changes,26 many newspaper articles only mentioned the embassy at first in 1972 rather than showing it through photographs.

Another visual moment, representing reconciliation and land rights, was also remarkably absent from newspapers of the day. In August 1966, Vincent Lingiari led a walk-off of 200 Gurindji workers and their families from Wave Hill in the Northern Territory as a protest against pay and work conditions. The protesters camped at Wattie Creek, where they sought the return of some of their traditional lands to develop a cattle station. On 16 August 1975, at Wattie Creek, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam transferred the Crown lease of Gurindji traditional lands to Lingiari, symbolically handing soil to Vincent Lingiari. Mervyn Bishop, an Indigenous photographer working for the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, and Barlow from the Australian Women’s Weekly were both present. The formal ceremony occurred under a shelter, and Bishop remembers that ‘as soon as the formalities had finished, I walked up to Mr Whitlam and I said, “Mr Whitlam, would you mind if we reshoot that situation again outside in the bright sunshine, with the nice blue sky?” And he said, “Very well.” … I said, “I’ll escort Uncle Vincent Lingiari out” … So, I positioned them, and arranged it so that Uncle Vincent had the deeds in his left hand and to hold his right hand out to receive the soil … I was using a Hasselblad, which is not a real fast-action camera … and I said, “I’m going to be taking a few pictures, then Keith’s going to be taking some pictures too.”’

8.3 Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pours soil into the hand of Gurindji landowner Vincent Lingiari (Wattie Creek), Northern Territory, 1975. Photographer Mervyn Bishop (Mervyn Bishop/Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. Reproduced with the permission of the Commonwealth of Australia).

Barlow remembers how he and Bishop took the ‘same photograph side by side, which is a very historic moment in terms of Aboriginal rights in Australia at the time’. Barlow’s colour images appeared in the Australian Women’s Weekly. Despite its now iconic status, Bishop’s image was held in storage at the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, where it remained unpublished for many years. But Bishop’s photograph has since been widely recognised and has gained importance. Other photographers also admire Bishop’s ingenuity and gumption in having the symbolic moment of the soil handover re-created in such a visually powerful way.

Bishop was the only Indigenous press photographer when he commenced at the SMH in 1963 and recalls that he was not conscious of overt racism during his eleven years with Fairfax.27 In 1974, Bishop began working as a photographer for the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, documenting ‘everyday’ issues. To avoid any suggestion that he was ‘like those white fella’ photographers who would represent Indigenous people in a negative light, he consciously asked Aboriginal people how they wished to be photographed and aimed to build up their self-esteem.

Over forty years after Bishop left the SMH, the absence of Indigenous journalists and photographers on newspapers is still a major gap.28 This is despite the profound contribution and importance of Indigenous photographers and Aboriginal photography, including the ascendancy of a ‘group of talented and committed photographer practitioners’ noted by Helen Ennis and others.29 In newsrooms, Bowers argues, ‘We need young Indigenous people to tell Indigenous stories … You need to get them trained up, visually—both moving pictures and still pictures—to tell their own stories about their own problems and their own cultures, because we can come in and we can do an interpretation of it, but it is that: it’s an interpretation of the way we see it … I think we need to get Indigenous people to tell Indigenous stories … And we should be looking at, and listening to, their story.’

Indigenous Australians have developed their own outlets for telling their own stories, including the creation of newspapers, broadcasting programs and internet sites. Shannon Avison and Michael Meadows see this as a reflection of ‘Indigenous perceptions of racism in mainstream media [and] essentially a failure by the public sphere to account for Aboriginal cultural needs’. These outlets, they argue, provide ‘opportunities for people who are regularly subordinated and ignored by mainstream public sphere processes’.30 Marcia Langton and Brownlee Kirkpatrick point to the significance of publications being ‘written and published in an Aboriginal context—unlike the “whitefella” media whose coverage of land rights is distorted by cultural concepts such as “newsworthiness”, business interests and just plain bias and ignorance’.31

One of the key Indigenous newspapers is the Lismore-based Koori Mail, which began publishing in May 1991 after a start-up loan from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission. The Koori Mail is a national publication that has traditionally included ‘a large amount of government advertising’.32 In 2000, the paper published 6000 copies.33 By 2011, it sold about 9430 copies and had 4000 subscribers throughout the country.34 The National Apology took place on the day the Koori Mail was published, which meant it had to pre-empt the story and was not able to publish photos from the actual event until two weeks later. The image chosen for the day of the Apology shows a group of women who are either from the Stolen Generations or are the daughter of someone who was.

8.4 The day of the National Apology, Koori Mail, 13 February 2008, page 1. Photographer not cited (Koori Mail).

In the United States, there is a conscious, overt tradition of ‘photo-journalism’ in which images are used as a form of activism, agitating for social change.35 In Australia, this also occurs, although the language around it tends to differ. One prominent example of advocacy journalism occurred in 2013, when the Global Mail did a visually striking exposé on the Indigenous housing crisis at Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory.36 The audio and visuals were by Ella Rubeli, and Debra Jopson was the writer. Rubeli was named the 2014 Walkley Young Australian Journalist of the Year for her ‘extraordinary’ use of video, photojournalism, print and multimedia in multi-platform storytelling.37 This is an interesting example precisely because it is not from a newspaper. Although the Global Mail had experienced newspaper journalists and editors, including Bowers as the site’s director of photography, it was an online-only outlet with a different funding model and purpose. A not-for-profit site dedicated to long-form and project-based journalism focused upon the public interest, the Global Mail was founded with philanthropic funding from internet entrepreneur Graeme Wood and operated between 2012 and 2013, closing after Wood said he would no longer fund the site and alternative funding did not eventuate.38 The Tennant Creek story, therefore, suggests not only the possibilities of online multimedia formats and new players with different agendas but also the economic challenges that new players face.

Since the end of World War II, Australian society has been transformed by immigration policies including the postwar policy of mass immigration. Still photographs have been identified as a key influence on public perceptions about immigration.39 Photographs tell migration stories that begin in a home country and end—if successful and sanctioned by government policy—in Australia. The mode of transportation is central to such images. In European representations of migration, for example, the train is ‘one of the enduring tropes’.40 In Australia, the ship or boat is the mode that has attracted the most attention and controversy, despite many postwar migrants arriving by plane.

Several photographers have had their own experiences of migration during the postwar period. For example, Tony Ashby’s parents were ‘ten-pound Poms’, British immigrants who received assisted passage. Ashby was born in Kent in England and came to Australia at the age of twelve. When he first arrived with his family, they were placed at a migrant camp. Russell McPhedran spent his early childhood in Glasgow, Scotland, and migrated to Australia with his family in 1950, at the age of fourteen. Stephen Dupont’s parents emigrated from Denmark in the late 1950s, and Julian Kingma’s parents, from Holland, were also part of the wave of postwar European migration.

From an early stage in that postwar migration push, Australian politicians practised careful visual stage-management around the arrival of ships. In 1945, the Labor government established the Department of Immigration and placed Arthur Calwell at its helm. Calwell had a history of turbulent relations with the press but, as immigration minister, recognised the significant role newspapers could play in promoting government policies to the public. He was very aware of the role of the visual in aggravating or calming Australian anxieties about immigration.

In April 1947, Calwell was suspected of being behind an incident when press photographers were prevented from boarding the refugee migrant ship Misr, which had docked at Freemantle, even though journalists were allowed on board. Calwell was asked about the photographic restriction in parliament. His denial was ambiguous. While he denied that he had issued any instruction preventing photographers from boarding, he said he had expressed a view that ‘emotional scenes’ of family reunions should ‘not be the subject of Press photography’.41 This was curious, because in other cases, images of immigration were judged very suitable for press photography. The issue seemed to be that the Misr was a ship that contained non-British immigrants, including some Jewish and Greek immigrants. The state president of the RSL said this contradicted Calwell’s claims of giving preference to British immigrants and—expressing some of the xenophobia Calwell was up against—described the ship as being in a ‘filthy condition’ and as having transported ‘an ill-assorted bunch of migrants’.42

Calwell was keenly aware of the importance of press photographs in particular, stating in his autobiography that early on in the postwar migration process, after accepting a number of Jewish refugees, ‘[o]ne newspaper printed a photograph of a very old woman who had to be carried down the gangway on a stretcher. The caption on the photograph described the woman as “the sort of migrant Mr Calwell is bringing to this country”.’43 Calwell expressed himself surprised by the extent of ‘xenophobia’ in the Australian community but had a visual way of soothing fears.44 Calwell explains in his autobiography that when shiploads of displaced persons arrived in Melbourne in late 1947, comprising men and women from Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, his department deliberately selected a ‘choice sample’ of:

one shipload with nobody under fifteen and nobody over thirty-five … all … had to be single … Many were red-headed and blue-eyed. There was also a number of natural platinum blondes of both sexes. The men were handsome and the women beautiful. It was not hard to sell immigration to the Australian people once the press published photographs of that group.45

On 8 December 1947, the Argus published, on page three, the headline ‘800 BALT MIGRANTS ARE HERE FROM EUROPE’ above a photograph showing immigrants who had just disembarked from the Kanimbla. The image showed Calwell’s selection of ‘handsome’ and ‘beautiful’ young adults listening to him give a welcome speech, with women prominently shown in the foreground. The caption underneath the photograph was ‘Fine new Australians … All are single’.46 The Sydney Morning Herald described them as ‘bronzed, athletic types’ in an article headlined ‘YOUNG MIGRANTS FROM BALTIC COUNTRIES REVEL IN AUSTRALIAN OUTDOORS’, noting that all were ‘fine swimmers’.47 This was a period of bipartisan agreement on population growth through immigration, and the press reflected that political consent. Overall, the images in newspapers represented immigration in generally positive ways, as beneficial for the country.48

Photographs played a very important part in the process of introducing Australians to ‘the other’. In 1949, Calwell was still occasionally heading to the docks to be photographed with new arrivals. He gave a ‘paternal kiss’ on the head to six-year-old Isobel Savery, Australia’s 100 000th British immigrant since the end of the war. Tellingly, he then recreated the action a moment later so that photographers could capture it. Calwell pointedly described the girl to the crowd and journalists as ‘this auburn-haired blue-eyed beautiful child’. She was given a doll, a koala and a box of chocolates, encouraging a benevolent and patriotic visual representation in newspapers.49

Immigration progressed and became more diverse after the slow dismantling of the White Australia policy,50 and then the embrace of a policy of multiculturalism under the Whitlam Labor government in 1972. Newspapers chronicled the increasing cultural diversity of Australian society, especially in metropolitan cities. Photographs of ‘ethnic’ festivals, family reunions at docks and airports, and community and individual achievements all highlighted how Australian society was changing. There were many photographs documenting the transformation through human-interest and biographical stories. Not all of the media or public attention to immigration was positive, however. In their analysis of Australian newspaper reporting of immigration between 1935 and 1977, Naomi Rosh White and Peter B White found that in the 1960s, immigrants were publicly defined as a social problem for the first time.51 This was often on the basis of limited access to social goods and benefits—a common theme in cross-cultural reporting of immigration, where immigrants are represented as a threat to the jobs or housing opportunities of local citizens.

In 1976, the first Vietnamese refugees fleeing conflict and persecution in their war-torn country arrived in Australia by boat, landing at Darwin Harbour on 26 April. The Northern Territory News gave the story front-page status, but the incident was not accorded such prominence in other Australian newspapers, indicating a lack of awareness of its significance.52 The Northern Territory News ran two photographs above the headline ‘VIETNAMESE REFUGEES CAN STAY’. The top image was of the boat moored in the harbour, paying attention to one of the defining tropes of migration photography—the mode of transportation. The lower photograph was a staged group shot of smiling young men in front of a government building.

8.5 First arrival into Darwin of Vietnamese ‘boat people’, Northern Territory News, 28 April 1976, page 1. Photographer not cited (Newspix).

While the first ‘boat people’ arrivals between 1976 and 1981 were received by the Australian public with press interest and general sympathy, continuing arrivals became a matter of increasing concern. Public discussion became more focused on connections with unemployment and the impact of people ‘jumping the immigration queue’.53 Boat arrivals were a major news topic during the 1977 federal election, and there were vocal claims that Australia was losing control of immigrant selection.54 As the number of people arriving by boat increased, opposition grew, and was reflected (and encouraged) by references in some newspapers to an ‘invasion’, a ‘flood’ and the ‘yellow peril’.55 Opinion-poll data showed that the Australian public’s opposition to boat arrivals increased steadily between the late 1970s and the early 2000s.56 In 1992, in response to a wave of unauthorised Indochinese boat arrivals, the Keating (Labor) government instituted a policy of mandatory detention, which required that all non-citizens arriving without a valid visa would be placed in detention centres.57

In 1996, after the Liberal Party’s disendorsement of her for xenophobic statements, Pauline Hanson became the first female Independent to be elected to the House of Representatives. She attracted extraordinary media attention and founded the One Nation Party. Both Hanson and her party represented a populist, conservative, anti-multicultural unease, including a specific unease about Asian immigration. Media reporters found she provided a remarkable degree of access compared with other politicians, who were far more circumspect.58 One photographer observes, ‘In a strange way, she was a breath of fresh air because she was so candid … Everyone just jumped at that.’ Hanson was not only accessible and verbally unfiltered, but also a distinctly visual phenomenon as a female politician, with red hair and bright lipstick, who sometimes draped herself in Australian flags. Hanson’s ascension also coincided with the development of digital cameras, especially from 1998 onwards, which meant photographers could be more mobile in covering her. Hanson was not only refreshingly ‘unspun’; she also campaigned in more physical settings with crowds and greater visual possibilities. Sometimes that extended into potentially threatening situations. Ray Sizer recalls Hanson speaking at Echuca in 1998, where it became ‘very, very aggressive’.

Increasingly, the Howard government seemed to be responding to Hanson’s lead and to her popularity within some sections of the Australian community, as demonstrated by its hardening stance on immigration and asylum seekers. Kate Geraghty was working at the Albury Border-Mail in 1999–2000 when Kosovo refugees were held at the Bandiana barracks near Albury–Wodonga as a temporary safe haven and then controversially sent back by the federal government.59 She describes how only one photographer and one journalist went ‘because we knew that they were traumatised’ and that to have a different photographer every time would not be helpful, especially as they were ‘going out there every day, nearly’. This was Geraghty’s first assignment ‘dealing with people who had suffered and who had fled war’. She learned ‘how to build trust … [with them by] spend[ing] time … [and] explain[ing] where you’re coming from’.

Between 1997 and 2000, the number of people held in detention centres quadrupled.60 The arrival of refugees and asylum seekers in Australia by sea became increasingly newsworthy and controversial. The Woomera Immigration Reception and Processing Centre in outback South Australia was particularly criticised for its poor conditions, including overcrowding. Charlton was sent to cover protests and a breakout of detainees at Woomera in 2000. This was a very difficult story for Charlton. He felt like he ‘was in another country, in a war-zone’, and describes it as probably the most confronting thing he has seen.61

Asylum seekers arriving by boat have captured public and media attention even though ‘usually only a small proportion of asylum applicants in Australia arrive by boat—most arrive by air with a valid visa and then go on to pursue asylum claims’.62 The focus on boat arrivals is undoubtedly connected to the media’s history of rendering such arrivals as a visual phenomenon since the 1970s, leading to much greater attention and anxiety being accorded to boat arrivals than to plane arrivals or visa over-stays. On 26 August 2001, the Norwegian container ship the MV Tampa rescued 433 survivors from an Indonesian wooden ferry that was sinking off the northwest of Christmas Island. The survivors persuaded the Tampa’s captain to sail towards Christmas Island and Australian territorial waters. On 27 August, the Howard government refused the Tampa permission to enter Australian waters. Australian special forces boarded the Tampa to prevent passengers disembarking at Christmas Island, denying them the right to claim refugee status in Australia. The asylum seekers were sent to Nauru for processing. This event dominated news coverage for over a week. The tough stance taken by Prime Minister John Howard was credited with aiding his re-election at the 2001 election.63

A key aspect of media reporting of that and subsequent events has been the attempt by various Australian governments to limit visual representations of asylum seekers. Several photographers view this as a determined effort to prevent humanising images of asylum seekers that might cause Australians to show more sympathy, and thus shift the terms of the debate. Visual control has more recently included photographers and journalists being manhandled, cameras being confiscated and photographers being forced to delete images of asylum seekers.64

In 2001, Wylie went to Nauru to photograph the asylum seekers who had been on the Tampa. They ‘had been stuck in the ocean, and it was really a case of them not having a face or a voice for weeks’. When the asylum seekers finally got off the boat and onto Nauru, they were put into a camp at the top of a hill. Wylie and her colleagues were on the outside of the fence, and the asylum seekers ran towards the fence, wanting to talk to them and get messages to their relatives. She was aware of the symbolic and social importance of stories like the Tampa and felt her role was ‘to give a voice to those people’, ‘to get the other side of the story, when no one had been able to speak to them, and they didn’t have a voice, and no-one had seen what they looked like. They were just people who … politicians were talking about and arguing about, but no-one had asked them their opinions.’ While Wylie was there, news came of the September 11 terrorist attack in the United States.

One photographer talks about the Australian military physically stopping them from taking photographs of the Tampa asylum seekers being moved: ‘the navy … were barging into us to push our boat … away’. And after the Australian government contacted the Nauruan government, a local fixer was warned by the Nauruan government that he would be arrested if he helped the photographer’s paper. Graham points out that Australian journalists and photographers were ‘not allowed to actually get to know or interview or [even] get to know a name or back story of any of these refugees’ because it would ‘personalise, [and Australians would] start to care … start to sort of understand that they’re people’.

Bowers was on Christmas Island as debate raged over the Australian government’s response to the Tampa. When asked how photographers illustrate the asylum seeker debate, he says, ‘Well, you can’t. That’s the whole reason they keep [them] off shore, so you can’t … get access to it. Only what they release. It’s a disgrace. They don’t want to put a face on it. If you see a face, if you can put a face of a kid who’s an asylum seeker there, people go, “Well, what’s the kid done wrong?” … So they try absolutely everything they can … Both governments are the same. The Labor Party and the Liberal Party … and in years to come I think it’ll be a great stain on this country, that we allowed children, particularly, to be incarcerated in these far-off places and we damaged them mentally and physically … I think it’s a disgrace, the way we’ve behaved over this, and I don’t think there’s any reason, no matter what they’ve done, that we should lock up children.’

Visual images have been central to recent debates about immigration and border control, and not all of them have been produced by the news media. Two days after the 2001 election was announced, the immigration minister, Philip Ruddock, told journalists, in a claim later proved to be false, that asylum seekers had threatened to throw their children overboard when approached by the Australian Defence Force. This claim was then repeated by Prime Minister John Howard and the defence minister, Peter Reith. A still photograph released to the media as evidence of children having been thrown into the sea was later found to be of an entirely different incident and actually showed children being rescued from a sinking ship by Australian forces.65 The false ‘children overboard’ claim was not corrected or retracted by the government prior to polling day, although doubts were known.66

Australia’s status as an inclusive, multicultural nation was also being challenged in other ways. On 11 December 2005, outbreaks of mob violence erupted on Cronulla Beach in Sydney’s south after a week of growing tension between groups of young men of Anglo-Celtic background and young men of Middle Eastern background. That day, thousands of people had gathered at the beach after text messages had been circulated calling for the targeting of men of ‘Middle Eastern appearance’ in retaliation for assaults on a group of volunteer surf lifesavers. Several incidents of mob violence and vandalism occurred during the day, followed by more retaliation attacks later that night.

Steve Grove identifies Cronulla as an example of the more challenging environments that photographers find themselves in, compared with journalists, who, he says, no longer ‘tend to get out of the office as much’. Grove notes how, at Cronulla, up to six photographers ‘were all on their own; they didn’t have reporters with them … all operating virtually independently [of each other] … They [were] all in different parts of Cronulla: one’s on the train … another one’s down somewhere else.’ Grove contrasts this with how, when he was out on the road in earlier years, ‘you went everywhere with a reporter … It was almost like a professional sin … if there was [not] a reporter there to write words about the picture that the photographer had captured.’

Andrew Meares’ coverage at Cronulla for Fairfax included shocking images of violence against individuals and the disturbing behaviour of the crowd. Meares writes about his experiences on that day: ‘While press photography can be callous it actually requires compassion. I wanted to show the brutality and I wanted to save [a man being beaten by the crowd] and realised the best and only option I had was to continue taking photos.’ But as the attack on the man continued, Meares ‘imagined he probably would have ended up on the ground and the crowd would’ve just kept kicking him. Then what? My photos couldn’t stop that. I felt pathetic.’ Meares was so close to the violence that he was struck by a beer bottle in the head, resulting in ‘two stitches and eight columns on the front page’.67

A page from the Daily Telegraph on 13 December used photographs from the riot to show clear images of individuals’ faces, accompanied by the headline ‘Faces of Hatred’. Readers were asked, ‘Do you know these people?’ and police contact details were provided. This was press photography as a policing and monitoring tool as well as an eyewitness account.

8.6 ‘Race Riot: Heroes and Villains’, relating to the riots in Cronulla, Daily Telegraph, 13 December 2005, page 5. Photographer(s) not cited (News Corporation Australia/Newspix).

In the following months, images of the Cronulla riot were subpoenaed from media organisations and drove police investigations and prosecutions. As Meares argues, this use of photographs may be problematic because many images reflect complex newsgathering processes and do not tell ‘the whole story’. For example, the press did not capture images of the night-time ‘retaliation raids’ following the main riot as these were more random and mobile, and occurred in darkness when neither eyewitnesses nor the police were present. Meares reflects that ‘responding only to the scenes depicted, and prosecuting those few faces captured on camera and splashed across the front page’ did not help to resolve the community tensions at Cronulla. More broadly, he asks whether the use of the photographs in securing evidence for the police might mean that the presence of photographers at such events ‘may not be tolerated under similar circumstances in the future’.68

In the decade following the Cronulla riots, asylum seekers continued to be represented as a political threat in some conservative, populist and nationalistic media discourse. Meanwhile, the Australian government’s policy of off-shore processing of asylum seekers, and restrictions imposed by both the government and by news organisations’ dwindling resources, challenged photographers’ ability to report. Geraghty’s photograph ‘Asylum’ depicts the arrival of asylum seekers at the processing centre on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea in October 2013. It shows Iranian Pezhma Ghorbani, aged twenty-six, and his fellow asylum seekers pressing identity cards against the window of a bus transferring them to the detention facility.69

8.7 ‘Asylum’: Pezhma Ghorbani from Iran (centre), along with his fellow asylum seekers, holds his identity card at the window of the bus after arriving on the second plane carrying asylum seekers to Manus Island in Papua New Guinea, 2 August 2013. Photographer Kate Geraghty, published in the North West Star (Kate Geraghty/Fairfax Syndication).

Not only was Geraghty’s photograph a humanising image of despair, but it also highlighted the issue of press access to detention centres. Just months later, high application fees for press visits to Nauru were introduced, effectively controlling, and limiting, media presence.70 Bowers says, ‘I tried to get to Nauru and they put up the fees for journalists to $8000 to apply for a journalist visa to Nauru. Now, you can’t tell me that hasn’t come from [the Australian] government … It’s a disgrace … [Even if you pay $8000,] there’s no guarantee … they’re going to give you a visa … The only stuff coming out of Nauru is sanitised.’

Some of the most extraordinary photographs of a refugee journey to Australia were taken by Barat Ali Batoor, who fled Afghanistan in 2012 and paid people smugglers to take him to Australia. Batoor had been documenting the displacement of his own Hazara people since 2005 and always intended to photograph his journey. The people smugglers agreed but only allowed him to take photographs once he was on the boat. In Indonesia he set out with ninety-two others for Christmas Island. On the second night, ‘the water got rough … our boat leaked and one of the engines stopped … We really lost our hope and [were] thinking we are going to die … I kept documenting whatever was happening … we turned back and [were] coming towards Indonesia … [it] took us around six to seven hours until … we saw a small island … our boat crashed onto the rocks, so we all jumped into the water and I took the last few photos when the people were in the water and trying to swim to the shore.’

The passengers survived. Batoor’s camera was destroyed in the sea, despite his best efforts to protect it. But the memory card with his images was unharmed. He was officially recognised as a refugee and resettled in Australia in 2013, after his images received widespread recognition following their publication in the Global Mail. ‘The First Day at Sea’ was awarded two Nikon Walkley Awards: Photo of the Year and Best Photo Essay.

Several photographers who have had close contact with asylum seekers were shaped by those experiences. One says that ‘talking to people here who are very anti-refugees, you almost want to say to them maybe you should go overseas and have your kids tortured, and burnt, and raped and pilfered, and then you come back and tell me if you think you want to move them … That’s one thing that I find hard in dealing with.’ Another speaks about the sadness in the eyes of children in what are effectively prisons, and wonders about the power of photographs to change the circumstances, given the visual fatigue that is now present: ‘The problem I think nowadays … though is … [people] see so much of it on the internet, on the TV, on their phones, on Facebook. Everywhere they look, they see grief. They’ve become, almost, nonchalant about it. So it takes an iconic image to actually make a difference these days.’

8.8 ‘The First Day at Sea’. Photographer Barat Ali Batoor, published in the Global Mail (Barat Ali Batoor).

One of those iconic images, taken overseas but with an impact on policy in Australia, was a photograph of drowned Syrian boy three-year old Aylan Kurdi, whose body washed up on a beach at Bodrum in Turkey. Nilufer Demir’s shocking images show a Turkish gendarmerie carrying the boy from the water. Within hours of being taken, the photographs were shared on social media. European newspapers debated whether to run the images, as dead children are normally not shown in newspapers, and especially not on the front page. But ‘almost every UK newspaper broke [that taboo] and ran an image on the front cover’ the next day.71 Although British Prime Minister David Cameron had initially said ‘we can’t take any more people fleeing from war’, within days he had agreed to accept 20 000 more refugees.72 In Australia, the images were published and widely discussed on television, radio and social media. Prime Minister Tony Abbott was also initially steadfast about not changing Australian policy but, following media, public and backbencher pressure, pledged $44 million in emergency aid to refugees in camps, and agreed to accept an additional 12 000 refugees from Syria and Iraq to resettle in Australia.73

Overseas responses to immigration are important in drawing Australian attention to the global scale of people seeking refuge. Ten years after the Tampa, Geraghty sought out asylum seekers who had been sent back to Afghanistan. She found some were dead, killed by the Taliban for fleeing, while the remainder lived in hiding and in fear. En route to Iran, Geraghty received the news that Reza Berati, an asylum seeker on Manus Island, had been killed. She was ‘the only media who photographed and covered the body-less funeral of Reza Berati, in Tehran with his sister and family’.

In 2015, Geraghty and journalist Ruth Pollard documented the Syrian refugee crisis in the Mediterranean for an Australian readership. She photographed privately funded boats rescuing refugees at sea. In Italy, when the refugees landed, Geraghty noticed how the authorities were helpful and welcoming. The authorities there had ‘a water truck and they were spraying down the cement wharf so that the refugees wouldn’t burn their feet, ’cause they didn’t have shoes on’. Geraghty recalls, ‘They were handing out balloons to the children. In Australia, refugees aren’t treated that way. And so just by photographing that stuff, you know, we were hoping to start a conversation; this is how others are treating refugees.’

Geraghty also photographed ‘a gentleman from Syria called … Abdullah and he’d just arrived on a boat from Turkey on a dingy. And I noticed that he had a big black … garbage bag. And then he disappeared behind a tree and then he comes back out and he’s wearing blue suit pants … the white shirt … tie … [and] doing his hair. And … in a bit of broken English and broken Arabic, he said basically … this is his first day of his life, and so he wanted to wear his best … suit. And I just thought … what a proud man … He was by himself; his family had been killed [in Syria] … and I just thought, the people who are fleeing … they’re human beings. They have pride, they have, you know, all the same emotions that everyone else does … I loved photographing that moment.’

Migration and refugees are a global phenomenon, and bringing events and perspectives from different countries home to an Australian audience is a crucial part of broadening out what is usually a very parochial debate around asylum seekers within Australia.

Australian media representations reflect the distinct formation of Australian national identity and how it has historically been shaped by colonial and postcolonial fears of Asian ‘invasion’, Aboriginal resistance and Muslim violence.74 One of the most striking findings of our research is the gap between the views of many press photographers and the management of the outlets they work for. Management decisions about news content are influenced by perceptions of audience expectations and concerns about limited resources. This means that the determination of many press photographers to show diverse and positive representations of Indigenous Australians and refugees, for example,75 which would foster audience empathy and understanding, and might spur political action in relation to their needs, is not always matched by a commensurate level of resourcing or commitment within their organisations. This is a source of frustration to many of the interviewed photographers.

Press photographers also face difficult choices when documenting shifts in Australian society. Social advocacy journalism requires photographers to document, for example, squalor and disadvantage in order to galvanise the public and politicians into action. While such images might sometimes achieve that, at other times—even if taken with the explicit purpose of helping in mind—they are criticised for contributing to a racist stereotype or being unsympathetic to the communities depicted. Photographs are open to interpretation, and responses to them vary. This has been especially true as social and government responses to Indigenous politics and to asylum seeker boat arrivals have become increasingly politicised, playing out as contentious issues in the media. Longstanding attempts by politicians and governments to shape visual representations of people affected by government policies, and even to suppress those visuals, indicate just how important those representations are.