FAY ANDERSON

NEWSPAPER PHOTOGRAPHS PROVIDE an illuminating reflection of Australian society and national identity. Many images of women, children and celebrity are considered ‘soft news’, but they are far from frivolous and reveal imagined and tangible societal values as well as important editorial strategies. By tracing these photographs, we better understand entrenched and changing ideas about women, social aspiration, sexuality, female empowerment, childhood and popular culture.

As Anne-Marie Willis argues, the existence of press photography itself generated events to photograph: ribbon-cutting ceremonies, prize and cheque presentations, ‘the grip and grin’, beauty contests and social events. They were sometimes arranged, performed and posed specifically for photographers, and the stories were usually pre-notified assignments from the pictorial editor.1 Many were also set-ups, as several photographers avow. The pre-arranged ‘soft’ photographs were often not actual events but occurred when photographers were sent out on ‘quests’ to take ‘hot and wet weather’ shots, images of children and animals, and the unusual and quirky. It was a skill, and early photographers were valued for ‘thinking outside the box’ and ‘making something out of nothing’. Whether soft news or staged, they offer us a unique insight not only into Australian society and identity, but also into the history of press photography.

Women in Australian newspaper photography have been historically marginalised, both in front of and behind the lens. Newspapers were professionally a male enclave, and the anecdotal and statistical evidence reveals that women photographers were discriminated against in recruitment, in the job, and in advancement until the 1980s and 1990s.2 The casual sexism and complex treatment of women that are revealed in some of our interviews were echoed in the visual representation of gender, in popular culture, and in the depiction of the domestic realm in newspapers, especially tabloid newspapers. Women were visible and idealised if they accorded with gendered expectations of beauty and morality, or concealed or vilified if they did not. Many stories about women were consigned to soft news. The political realm was more contested as women gained equal rights in the 1970s, but they were still largely absent in hard news images. Overall, women tended to be visually represented at the extremes: as successful, moral, beautiful, criminal or victims. The coverage usually combined didacticism and diversion. Consequently, press photography produced through story assignment and editorial intent both reflected and influenced social, marital, maternal and aesthetic aspirations.

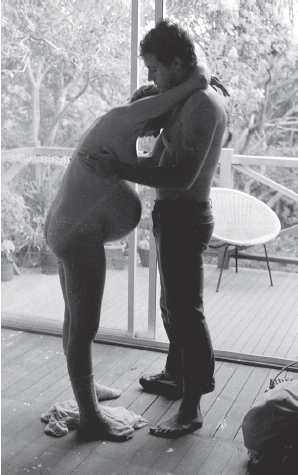

Daily newspapers in the nineteenth century were exclusively aimed at a male audience and focused on commerce, politics, shipping and law.3 By the 1920s, a greater focus on a female audience was accompanied by the growing use of photographs. Particular sections—including the women’s page, entertainment, advice columns and social pages—were increasingly illustrated with images and skewed to a female readership, or what male editors imagined women were interested in. At the same time, with the encroachment of consumer culture, women were identified as a source of revenue,4 establishing a link between editorial press photography of this nature and advertising and advertorial content. The domestic realm became highly valued; home economics, kitchens, interior decoration and recipes for the family were heavily promoted.

Until the late 1960s, women’s and social pages were a staple of newspapers and aimed exclusively at female readers, with photographs of farewells and arrivals on P&O cruise liners, afternoon teas, debutantes and ‘coming out occasions’, parties and galas. Men were the supporting players rather than the primary visual focus, although it was always implicitly understood they were the conduit to social position and elevation. The pages were orientated towards the middle class or aspirational, with occasional coverage of events on more prosperous real estate such as Government House.

The social run has remained vivid in photographers’ memories because it was usually the first round they were sent on after their cadetship or, as Bryan Charlton recalls, when they were ‘slowly let off the leash’.5 It was usually an unpopular assignment. Julian Kingma and others regarded trawling around restaurants, clubs, anniversaries and social events as ‘boring’ with ‘not a lot of photographic merit in it’. Yet the social round functioned as an important training ground, where the photographers learned how to approach their subjects. Karleen Minney observes that the social pages were photographically unexciting but, as a gallery, they were always popular. As Grant Wells notes, ‘faces sell’. They also, as Minney points out, can have a special resonance for the people shown in the photographs or their family members. But the public appetite for viewing social events was a source of frustration for many of the interviewed photographers, who were politically conscious and far more interested in depicting social justice and diversity.

These social and women’s pages reflected the commodification of marriage: engagements, weddings, receptions and honeymoons. Regular pages included ‘Saturday Brides’, ‘Weekend Weddings’, ‘Wedding News’ and ‘Newlyweds’, along with special features such as the ‘First Brides of Spring’. The fiancées and wives of sportsmen were regularly featured and privileged but were not sexualised or given the same prominence as their contemporary successors, the ‘WAGs’. Charlton, a sports photographer, is mystified by the fact that the partners of sporting people are now sometimes more popular than the sportspeople themselves.6

A less socially acceptable aspect of marriage was also visually covered. Until the Whitlam government introduced no-fault divorce, marital separations and divorce were popular newspaper fodder. Tabloid newspaper Truth sensationally described in 1940 the ‘tales told in divorce court’ where ‘there’s no limit to the twists, turns, pranks and wiles of human nature’.7 Before the passage of the Family Law Act in June 1975, a marriage could only be dissolved if one party could prove that the other was at fault in the breakdown of the marriage. ‘Matrimonial offences’ such as adultery, cruelty or ‘desertion’ had to be proven before divorce could be allowed.8 Photographs of the couple, and even their children or property, illustrated sensational divorce announcements and cases.

Mothering was considered equally newsworthy, but the coverage was also selective. As numerous critics observe, newspapers reinforced and perpetuated idealised concepts of motherhood based on spousal dependence and self-sacrifice. The pictorial depiction did not extend to visibly pregnant women, who rarely featured in newspapers until the 1980s. The press, as Roslyn Weaver and Debra Jackson note, also played an equally significant role in constructing and reflecting images of aberrant and deviant motherhood.9 This early and simplistic media construction of motherhood and maternity began to change in the late 1980s though. Helen Ennis traces the orientation towards realism in Australian photographic practice. Its emergence in broadsheets during the 1980s paralleled greater gender representation among the photographic staff.

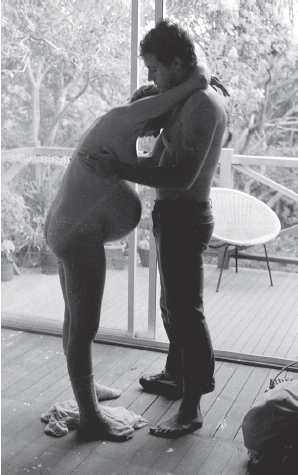

In 1984, the SMH decided to cover a medical story about home births, and the pregnant woman who was featured asked specifically for a female photographer. Susan Windmiller, who had recently completed her cadetship with the SMH, was assigned. On her arrival, she found the woman already naked and in labour. Windmiller discreetly took about ten photographs, including an image of the woman embracing her husband, who was supporting her during a contraction. The photograph was taken in silhouette. Despite this being a striking image, another photograph—of the happy couple after the birth, holding their baby—appeared on the front page. The silhouette photo was considered ‘too confronting’ and graced page three. Windmiller recalls the ensuing controversy: the switchboard was jammed on the day of publication, and during the following week, there were letters to the editor about whether the image of the woman naked should have been published. The silhouette image was named the best SMH photograph of the week. Although the Sun photographers took pictures of ‘page-three girls’ and ‘saw no problem with their images, they removed my photo, which had been posted on the wall. Several men found it offensive and put it in the bin.’10

9.1 Home birth by Amanda Mooy-Malone, at Naremburn, 14 March 1984. Photographer Susan Windmiller, published in the Sydney Morning Herald (Susan Windmiller/Fairfax Syndication).

Despite this growing move towards realism, images of ‘normal’ mothering featuring pregnant or post-pregnant bodies or breastfeeding were considered visually unappealing. By the 1990s, mothers were more visible, but usually when they accorded with an aesthetic ideal such as a celebrity ‘baby bump’, ‘yummy mummy’ or ‘milf’. The ‘yummy mummy’ ideal arose from increasing media attention on celebrity mothers, particularly after Annie Lebowitz’s nude portrait of actor Demi Moore, when Moore was seven months pregnant. The photograph famously appeared on the front cover of Vanity Fair in 1991. While successive celebrities have emulated the pose, Weaver and Jackson critique the pressure it puts on women to return to and maintain pre-pregnancy looks, body weight and fashion sense.11

While the pictorial representation of motherhood has changed, photographs of social events have also become less traditionally gendered and more democratised, no longer restricted to a particular class. Several photographers mention Angela Wylie’s enchanting 2005 photograph of three unknown young women caught in a wind tunnel at Oaks Day, squealing with joy as they try to hold onto their dresses, hats and drinks. Wylie describes it as ‘just fluff really, and nothing to do with sport or the racing’. She had the time to walk around and look for it. ‘I was standing in a place where there was nice light, hoping I might be able to get a good picture of someone’s hat flying off, and then I heard these squeals.’ That ‘piece of fluff’ ended up ‘probably being my most famous picture’, she says.

The democratisation of imagery is partly attributable to the introduction of visually orientated newspaper weekend magazines and partly to the more recent arrival of a multimedia platform that gives staff photographers a new outlet for their work. As Ennis observes, the resulting photo essays, social documentary and sublime portraitures permit a more expansive visual interpretation of gender, race, poverty, Australian identity and contemporary life.12 Groups who were once demonised or invisible, such as the gay community, now featured. Indeed, the Mardi Gras has become almost mainstream in some newspapers. The documentary approach of showing ordinary people’s lives and pain in close detail, which first gained popularity among American and European photographers, began to feature more readily in Australian newspapers.13 Although photo galleries and sound slides have not always provided the opportunity for longer-form journalism in the way some photographers had hoped the new methods would.

There are still some visual echoes of the past. Pictorial stories still focus on social events, ‘bathing beauties’, the ‘party of the week’, fitness, body language and ‘faces’. For paparazzi, the wedding, the honeymoon and the first-baby shots are the ‘Holy Grail’.14 While once socially unacceptable behaviour and a greater cross-section of the community appear in newspapers, the visual can still provide a forum to judge the lives of others.

Long-serving Shepparton photographer Ray Sizer recognises the universal appeal of ‘hatches, matches and dispatches’. Newspaper pictures of babies and children were regarded as a form of good news. Baby competitions and baby quests were a common feature and, in the 1930s, offered an escape from the privations of the Depression. Today baby and toddler shows and more sexualised child beauty pageants continue to attract visual interest, but the latter, along with the ascendancy of ‘pageant mothers’, also attracts media curiosity and ridicule.

Until the 1970s, babies sometimes appeared naked, and the celebration of whiteness was explicit. Aboriginal babies and children were depicted differently, and their images reinforced notions of paternalism, racism and protection. The captions accompanying those images often portrayed Indigenous children as exotic or primitive when they were photographed in their communities, or in need of care when they appeared in hospitals and children’s homes. Race was visually marked.

Many photographs of children functioned as light relief.15 The first day of school, Christmas, Easter, agricultural shows and summer were all excuses to feature children. On quiet news days, photographers were sent on ‘quests’, when they roamed, looking for a picture. Photographers would sometimes use their own children, and several concede that parenthood influenced their work. Stephen Dupont says he approached photography differently and was very affected by the suffering of children after the birth of his daughter. His emotions allowed him to convey something ‘different and more strongly’.

9.2 ‘The Women’s World’, Courier-Mail, 26 July 1935, page 20 (News Corporation Australia/National Library of Australia).

Stories involving the suffering of children—either due to illness, loss, accidents or as victims of crime—are identified as the most confronting assignments. The ‘lost child’ is central to colonial and contemporary experience and has long haunted the Australian imagination.16 The disappearance of the Beaumont children—Jane (nine), Arnna (seven) and Grant (four)—in Adelaide on Australia Day 1966 had an extraordinary effect on the Australian psyche. Fifty years later, their case is still listed on Crime Stoppers, with a million dollar reward, the poster illuminated by their radiant faces. More recently, awareness and acknowledgement of family violence, child abuse and paedophilia have resulted in a new and necessary visual trope: the victim in silhouette.

9.3 Front page of the Advertiser, 28 January 1966, with the headline ‘Massive Hunt Fails To Find Trace Of Children’, relating to the missing Beaumont children case. Photographer not cited (News Corporation Australia/Newspix).

Two striking photographs reveal a different, less mediated era and the immense visual power of children. One of the most haunting photographs is Steve Cooper’s 1986 photograph of a police officer gently carrying the dead body of a three-year-old girl. And in 1970, Mervyn Bishop was on the early morning round when he took one of his most celebrated photographs, of a nun, Sister Ann Bourne, carrying a small boy into St Margaret’s hospital in Darlinghurst after the child had swallowed medication from his mother’s pill bottle. As Bishop was printing the image, renowned photographer Bob Rice, who was in the darkroom, exclaimed, ‘Oh mate, what a beauty. Bisho, what a beauty!’ The photograph ‘didn’t get a run in the Sun but the SMH used it on the front page the next day’, Bishop explains. Years later, the boy who featured in the photograph had become an ear, nose and throat specialist. He called Bishop and they met at one of the photographer’s exhibition openings. His mother, who had initially been unhappy about the photograph, had changed her mind and had taken an interest in Bishop’s career. Later captioned ‘Life and death dash’, Bishop’s image earned him the News Photographer of the Year Award.17

Since 1988, the growing recognition of child vulnerability, sexual exploitation and the rights of parents and children has had a profound effect upon ideas of privacy and informed consent, and has resulted in legislative changes. When the Commonwealth Privacy Act 1988 was enacted, media organisations in the course of journalism were exempt, provided they met certain requirements, including being publicly committed to standards that deal with privacy.18 The Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance Code of Ethics and the Australian Press Council’s Privacy Policy are two such standards, but most news organisations apply additional codes of conduct relating to children. Fairfax’s Age specifies that ‘special care should be taken when dealing with children (under the age of sixteen) and the editor must be informed when children have been photographed or interviewed without parental consent’.19 The Australian’s code states that ‘extreme care should be taken that children are not prompted in interviews, or offered inducements to cooperate’; employees are instructed not to ‘identify children in crime and court reports without state specific legal advice’ or to ‘approach children in schools without the permission of a school authority’.20 Consequently some of the prosaic photographic routines surrounding children—hot weather photographs, quests and spontaneous images without permission—have disappeared.

Many of the interviewed photographers reflect on the changing regulations and ethics: parental permission, police checks and clearances, and protocols at schools. Some admit they now feel uncomfortable raising their camera at anyone in the street. Rick Stevens recalls an earlier time, when the camera identified him. In his later years, though, ‘if I had a job at the beach, I wouldn’t march across the sand with a camera’. The impact of the privacy laws over the last thirty years is described by Sizer as ‘incredible’, particularly for regional and community papers, which photograph local, daily life more extensively. He recalls that ‘virtually every baby born’ in Shepparton would have a picture published in the paper. Another photographer recognised the necessity of parental consent after his newspaper published a child’s photograph and the mother had to move house because she had escaped an abusive relationship.

One photographer experienced the ramifications of increasing public concern about the depiction of children when they attended a world gymnastics championships competition and returned to the office with some beautiful shots of young Chinese gymnasts in full flight. Unfortunately, none of what the photographer considered to be the best pictures were published because they featured ‘crotch shots’—young girls with their legs spread-eagled while performing amazing athletic feats. The fear that the images could be misused and misinterpreted guided the editorial decision not to publish.

Some editors still transgress, and the Australian Press Council continues to receive complaints about the visual treatment of children.21 The basic privacy accorded to all children is not always provided to the offspring of public figures and celebrities, who are stalked and photographed by the paparazzi. Images of Princess Mary and her children in their bathers while on holiday at a Byron Bay beach in 2015, for example, were splashed across some news sites.

The pictorial depiction of women has also sometimes shifted. Julie Ustinoff and Kay Saunders observe that notions of ideal womanhood and celebrity are just two of the many and varied concepts that have informed our national identity. Masculinised Australian icons such as the Anzac, the emergency services hero and the surf lifesaver have been privileged in images of national identity.22 The rare exceptions, though, are a number of photographic genres that focus on female beauty: Miss Australia, the beach girl, and the more contentious ‘page three girl’.

In 1907, a Sydney-based gentlemen’s magazine, the Lone Hand, organised the first nationwide contest to find Australia’s ‘ideal woman’.23 Since the first Miss Australia was crowned in 1926, the competition established both the standard and type of young woman deemed representative of the ideal white, Anglo-Australian woman.24 Subsequent contestants and winners of the coveted title gained celebrity status and appeared frequently in newspapers.

Tania Verstak, a 21-year-old Chinese-born Russian immigrant who won the competition in 1961, was of particular significance as the first ‘new Australian’ woman to win. As Ustinoff and Saunders argue, Verstak’s ‘manner, subtle exotic beauty and unreserved public appreciation of the nation and its people endeared her to many; she was an ideal ambassador for both the charity she represented and her country’. Verstak’s crowning reflected ‘a manifest attitudinal shift in the construction of (feminine) national identity’ and symbolised the success of Australia’s postwar immigration policy.25 Verstak was a constant presence in the newspapers during her ‘reign’, and a parade through the streets of Sydney was held in her honour after she won Miss International. Terry Phelan’s luminous picture of Verstak looking over her shoulder ran on the full front page of the Sun News-Pictorial. Beauty contests still have currency and the power to create celebrity, evidenced by Jennifer Hawkins, who won the Miss Universe title in 2004 and represented ‘a quintessential Australian contestant’.

9.4 Sunday Mail ‘Sun Girls welcome the US Air Force’, Courier-Mail, 22 April 1959, page 1 (News Corporation Australia/National Library of Australia).

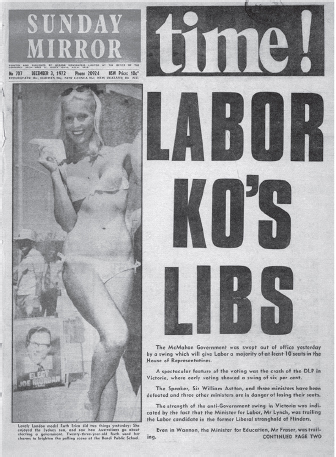

Another pictorial symbol of Australian womanhood was the ‘girl in the bikini’—a popular staple of many Australian newspapers, with continuing resonance. The early images followed common visual conventions: women were a passive part of the landscape, and were displayed to be looked at.26 In some examples, women simply functioned as a gratuitous decoration for men. In 1959, the Courier-Mail published a photograph of Sunday Mail ‘Sun Girls’ dressed in bathing suits and Digger hats holding a kangaroo on a lead and welcoming an American flier. Images of ‘beach girls’ posing with fluffy animals and four-legged creatures, including zebras and donkeys, were equally popular.

These women’s pictorial visibility was entirely linked to their physical allure, but unlike the professional model ‘pin ups’, they were often enlisted by photographers on the beach or in parks. This approach captured the sporty, outdoors persona emblematic of Australian cultural identity, but it was also convenient. Every photographer from this era remembers ‘looking for pretty girls’. The women’s names and suburbs were often included in the caption to promote a girl-next-door persona, but the convention was dropped when several women received ‘creep phone calls’.27 For Guy Magowan, the ‘worst thing’ when he was at the Daily News was being sent out to find a model: ‘Go down to a beach on a hot day, take your shoes off, roll up your pants, and walk around with a camera, asking some woman, “Would you mind having your picture taken?” Some guys were good at it, but I wasn’t that good at it. You couldn’t do that now; you wouldn’t do it.’28

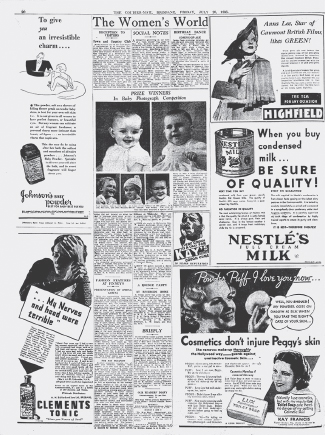

The ‘hot weather’ photographs reflected prevailing attitudes about women, public space and the centrality of beach culture, as well as a newspaper’s commercial strategy. They were intended to brighten the paper up and be ‘good to look at’. Anne-Marie Willis observes that for as long as photographs have been used in newspapers, the trivial and the serious have occupied the same page. Images of attractive women were juxtaposed and competed on the same or opposite pages with copy on hard news or images of serious men on ‘a mission’.29 On 3 December 1972, for example, the Daily Mirror published a photograph of a model posing incongruously at a polling booth at Bondi alongside the announcement of the Whitlam government’s historic election victory.

9.5 London model Ruth Erica in a bikini outside a polling booth at the Bondi Public School. Sunday Mirror, 3 December 1972, page 1. Photographer not cited (News Corporation Australia/National Library of Australia).

Even inclement weather didn’t prevent newspapers from printing images of women in bikinis. The Daily Telegraph captioned one photograph, ‘Threatening skies couldn’t keep 18 year old Jenny Austin away from the beach.’ Surrounding the photograph were reports on an amputee being kicked to death, a petrol drought and the rescue of a young refugee.30 The beach girls were young, often still in their teens, and signalled an emerging visual trend in the 1960s: the transition from ‘young people’ (as they were referred to in the newspapers) to teenagers. The teen page reflected the emergence of the ‘teenager’ as a new kind of entity: as consumers and, for young women, as a physical ideal.

Not everyone was comfortable with the growing permissiveness. Bruce Howard relates a story about one of his editors at the Herald who didn’t like seeing a girl in a bikini because it showed her navel. ‘He would walk out of the picture conference into the phone room next door to ask the girls if they were offended by it,’ Howard recalls. ‘And if, you know, they thought it was alright, he’d come back and say, “Aw yeah, oh okay, but not page one”.’

This editor’s concerns aside, there has been a long tradition, since the 1940s, of using women ‘to express ideas and ideals’, as Kate Evans observes.31 Madeleine Hamilton chronicles the changing meaning of pin-up girls: during the war, they were depicted as the ‘approachable girl next door’ and symbolised private and personal obligation. Hamilton demonstrates that these women were assertive and confident and, when involved in the production of pin-up material in the 1940s and 1950s, displayed significant agency in their visual presentation.32

Fashion photography has an equally long pedigree in Australia. It was an important training ground for photographers and models, and provided a roll call of renowned photographers, including Max Dupain, Athol Shmith and Helmut Newton. In 1938, Newton, who was a German Jew, fled the Nazis and moved to Australia. After serving with the AIF for five years, he embarked on his celebrated photographic career.33

According to Hamilton, by the 1950s, the pin-up often evoked a more erotic aesthetic, providing a foundation for the sexualised imagery that appeared after the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s.34 The evolution began in 1959, when the Sydney Daily Mirror introduced its ‘page three girl’, later known as the ‘Mirrorbird’. Inspired by its success, the Mirror’s rival, the Sydney Sun, also adopted the feature in the 1960s. The images comprised a ‘cheesecake photo’ of a model, usually in a bikini and typically located on half of the third page, the second most prominent page of the newspaper, and sometimes on the first.35

Any analysis of the Australian ‘page three girl’ comes with a number of caveats. First, this trend should not be conflated with the widespread publication of ‘hot weather’ photos; the ‘page three girl’ provided different erotic capital. The most extreme example, identified by Willis, was the Mirror’s schoolgirl competition in 1980, in which the women were featured in a thumbnail wearing a school uniform and in an accompanying but larger bikini photo.36 As Willis explains:

The Mirrorbird achieves the unique distinction of appearing as sexually alluring as possible while remaining within the bounds of propriety. Her bikini might be tiny, but she never appears topless or naked. Fingers seductively fiddle with bikini strings or hands are placed on hips or thighs, near but never touching the pubic area … The posed bodies [are] sexually charged but the expressions on the girls’ faces deny this.37

Second, the London Sun did not inspire the antipodean version of the ‘page three girl’. It was the other way around. Rupert Murdoch, the owner of the Mirror, transformed British news photography when, in 1969, he added the Sun to his growing media empire and published a photograph of a topless model. It became a daily feature, driving the circulation, with regular models attracting national prominence and provoking conflicting discourses around objectification, empowerment and commodification as aspiration.38 Darren Tindale, a former picture editor of the Sunday Herald Sun, says Australian readers would not have tolerated nudity because they regarded themselves as more sophisticated.39

While the hot weather photographs provided a vital apprenticeship for the younger photographers, page three images were mainly ‘a senior photographers’ job’. Verity Chambers recalls that technically and stylistically, they were ‘extremely difficult’. Stevens and Lorrie Graham were both briefly and unusually trialled as page three photographers when they were cadets. Both admitted that they were not very good because they posed the women as if it were a fashion shoot. Yvette Grady shot both high fashion for the Australian and ‘page three girls’ for the Daily Mirror. She explains the difference: ‘When I shot page three girls, I was shooting them in a very modest way, with their legs crossed away from the camera. Neville Whitmarsh said, “Yvette, you’re shooting them incorrectly” … He taught me that I had to shoot with the legs crossed but with the butt towards the cameras so you get this lovely, leggy shot. It was more sexualised, whereas with the Australian, it wasn’t. It was about beauty. It was about beauty and art.’

The images were shot on medium format because the ‘quality had to be perfect’, and ‘lighting was everything’ for both fashion and page three features. You also had to ‘see what form a body takes’, Chambers explains. Grady adds, ‘You can shoot the most beautiful woman in the world; if you don’t know how to work with natural light, you can ruin her.’

‘It was a senior job; it wasn’t that easy. Printing them was really hard,’ recalls Chambers, who printed the photos early in her cadetship. ‘Neville Whitmarsh would come up in the darkroom with a cigarette hanging out of his mouth and try to give you tips on how to print them. They were perfectionists about it and if you did a bad print you’d be admonished quite strongly.’

It was considered the most important image that was published in the Mirror, and Chambers lists the masters: Warwick Lawson, Neville Whitmarsh and Wayne Jones. Ivan Ive, a photographer for almost fifty years for a series of newspapers including the Sun, and who occasionally moonlighted as a cover girl photographer for Pix magazine, was another who specialised. Ive also mentored Russell McPhedran when he was a fledgling cadet at the Sun and whose daily photos became known as ‘McPhedran’s girl’.

9.6 Photographer Ivan Ive with model Marlene Saunders (Fairfax Syndication/National Library of Australia).

Occasionally, the genre revealed contradictions in the overtly masculine workplace. Banter and suggestive chatter sometimes permeated the news-room, but as Chambers notes, it was the culture of the time. In 1967, before Grady’s arrival from Canberra, Mirror photographers were given a mandate to ‘get rid of all naked photographs of women pasted on the dark room walls and all the page three girls as well. Everything had to be removed,’ Grady recalls, despite being assigned to photograph the latter. Graham describes her experience of photographing ‘page three girls’ as ‘weird’: ‘And all I was saying to these girls is, “I actually really don’t understand why you’re doing this” … It was very odd … I mean, obviously, it didn’t work out … There may have been some hidden agenda.’

The demise of the ‘page three girl’ in Australia did not occur because of increased prurience or greater sensitivity to the objectification of women but rather cynical editorial pragmatism and waning readership. According to McPhedran, Derryn Hinch, the new editor of the Sun, stopped the publication of ‘page three girls’ because he wanted to upgrade the photo, and it wasn’t ‘his style’. On numerous occasions, the Mirror had attempted to cease page three, but according to Willis, the editor was inundated with letters of complaint. When the Mirror merged with the Telegraph in 1990, the ‘page three girl’ was finally dropped. The ‘page three girl’ has been more enduring in the United Kingdom, despite the collective feminist protest under the ‘Boobs Aren’t News’ banner in recent times. In January 2015, the Times reported on its demise, but the Sun appears to be continuing the tradition online.40

The visibility of women in newspapers was largely dependent on the currency of their beauty and the commercial appeal of the private domain. The visual representation of women in politics was more complicated, and even when they should have featured in hard news, they were often trivialised while men were photographed doing ‘serious work’. In 1978, Gaye Tuchman pointed to two aspects of women’s ‘symbolic annihilation’ from the public sphere: distortion and absence.41

As Australia’s first female prime minister, Julia Gillard presented as a visual novelty. She drew attention to this herself, both in her remark about male politicians in ‘blue ties’ and in comments she made after leaving office, noting that she had to put a lot of thought into what she wore in terms of making her clothes look unremarkable and trying not to draw attention to them. Graham suggests that in photographs, ‘women politicians particularly cop it. Because actually there’s a weird double standard about the way they look and the way they dress, so there are all these kind of nit-pickety things that people are constantly looking for.’

An early indicator of what was ahead for Gillard was the public mocking of her following a photo shoot in her kitchen, which showed an empty fruit bowl, interpreted by some as symbolising an ‘empty house’. Marian Sawer notes that Gillard was subjected to endless media commentary for having an ‘unnaturally spotless’ kitchen with no fruit in the fruit bowl, as depicted in an image that originally appeared in the Sun-Herald on 23 January 2005. According to a staffer, Gillard had just returned from overseas and had not even unpacked, but the metaphor of the empty fruit bowl ‘proved irresistible to many commentators’.42

The story was part of the media landscape that led Opposition senator Bill Heffernan to describe Gillard, who did not have children, as ‘deliberately barren’—a statement for which he later apologised.43 The Liberal Party’s 2010 campaign against Gillard seemed to deliberately highlight opponent Liberal leader Tony Abbott’s traditional family. But it also promoted his sporting prowess and machismo, with Abbot appearing for photo opportunities in ‘budgie smugglers’ and CFA gear.44

9.7 Julia Gillard, pictured in her Altona home, 22 January 2005. Photographer Ken Irwin, published in the Sun-Herald, 23 January 2005 (Ken Irwin/Fairfax Syndication).

Another key visual moment involving Gillard, and symbolising the treatment of female politicians, occurred at a 2011 rally, when Tony Abbott infamously stood next to signs that read, ‘Ju-Liar, Bob Brown’s bitch’ (referring to Bob Brown, the leader of minority government partner the Greens), as well as ‘Ditch the Witch’, featuring a drawing of Gillard on a broomstick. Multiple studies have documented that news media coverage disproportionately focuses upon how women politicians ‘look or sound, what they wear, or how they style their hair’.45 News media are more likely to focus on women candidates’ personal life, appearance and personality, while male candidates receive more news attention for their policy positions and policy priorities.46 The treatment of Gillard had antecedents. Joan Kirner was subject to a particularly vicious campaign; on the announcement of her election as premier of Victoria, Truth ran a photograph of Kirner in a bathing suit headlined, ‘MISS PIGGY FOR PREMIER’.47 Much has also been written about the pictorial representation of Cheryl Kernot, Amanda Vanstone, Bronwyn Bishop, Natasha Stott-Despoja, Kate Ellis and Pauline Hanson.

Several photographers noted Gillard’s visual treatment and her appeal. Although primarily a sports photographer, the Daily Telegraph’s Phil Hillyard gained extraordinary access to document Gillard’s first week in office, and he went with ‘fresh eyes’, which helped him capture her trust. His black-and-white images offered a candid insight into her working life behind the scenes, and conveyed an intimacy that came from Gillard being comfortable in his presence.

One image showed Gillard at what appeared to be a boring meeting, with one of her high heels kicked off under the table. It was the type of candid moment that Hillyard was looking for. Hillyard’s editor ran thirteen pages, just of his pictures, on the Saturday, all in black and white. Hillyard says he felt the press were very hard on Gillard as her term went on, and he was impressed with how she worked and by what’s required of the job. Andrew Meares notes that the publication rate with Julia Gillard photographs was very high; if they took a picture of her, there was a high probability that it got published. That was ‘partly’ to do with gender—she was the first female prime minister, and her clothing was ‘different everyday’—but she also ‘had a vibrant wit and laughter and was not afraid to show that through photographs’.

Like images of women and children, celebrity and popular culture have long been driving forces in press photography. Michael Schudson refers to the ‘journalism of entertainment’, with its distinctive formats and pictorial style, accessible language and photographs.48 In Australia, scandal and entertainment news proliferated during the early twentieth century, with an increasing use of artists’ illustrations and photographs.

Images of Hollywood ‘movie stars’ filled the entertainment sections of Australian newspapers, joined later by television personalities, entertainers and sporting identities. A recent and lucrative addition are the ‘reality stars’ who feature in a slew of reality television programs and are famous for simply being famous. Graeme Turner emphasises the tradition of celebrity in Australia and its ‘cultural pervasiveness’.49 The local Australian celebrity plays an important role in the ‘elaboration of cultural identity’.50 And sometimes the international celebrity is also co-opted within the Australian setting.

The benchmark for wannabe celebrities is the Kardashian family, who have marketed a global media empire with a net worth of $300 million. Charlton comments on the current obsession with celebrity: ‘I don’t know who they are and I don’t care who they are. They take up more space in the paper and news has changed.’51 Celebrity culture predated modern communication technology, but the rise of mass communication facilitated a seismic expansion in how it was consumed.52 In addition, celebrity moved beyond traditional entertainment content into hard news domains. Social and digital technologies are a vital part of this story, facilitating the sharing of rumour, gossip and images through memes and other formats. Often this content has its genesis in images from news reporting, or it is transferred across from citizen images and even selfies.

Philip Drake and Andy Miah note how new online media forms have reconfigured the nature and ubiquity of celebrity production.53 In 2014, the British pictorial tabloid the Daily Mail, the leading online newspaper in the world,54 launched its Australian version. The Mail’s critics attribute its popularity to its daily diet of celebrity reports featuring the ‘sidebar of shame’, which includes a thumbnail image and an attention-grabbing heading, mainly focusing on the appearance, weight, age and conduct of female celebrities and various royals, and often accompanied by vicious public comments posted at the bottom of the reports.

Photography in Australia is tied inextricably to the nation’s imperialist and colonialist past.55 Several present and former picture editors say that the royal family has always been a circulation booster despite the move away from ‘Empire’ as a dominant aspect of Australian identity. There is also, as Chambers notes, ‘a celebrity status attached’. While newsworthy, the first royal visit to Australia did not auger well when Prince Alfred, the fourth son of Queen Victoria, was shot in an assassination attempt in 1867. The Prince recovered and newspapers printed pages of illustrations.56

The Australian press largely adhered to the early British deference towards the royals. For two years, and unlike the American public, the Australian and British public remained unaware of Wallis Simpson’s relationship with Edward VIII and the looming abdication crisis due to a concerted press campaign to cover it up. The story broke in Australia in October 1936, with photographs of Simpson and her palatial new home appearing in December.57 Press photographers in the United Kingdom were increasingly less reverential by the late 1960s, and Princess Margaret became a pictorial favourite. McPhedran made the pilgrimage to Fleet Street in the 1960s and secured a position at the London Daily Express when Bob Hassell, the royal photographer at the Express, told him that if he ‘fogged’ (exposed to light) his film of Princess Margaret water-skiing, he would give him a trial. McPhedran duly complied and worked for the Express for six years.

McPhedran says the Australian royal tours were always memorable. Keith Barlow agrees, ‘they were amazing things to cover’. Possibly the most notable was Queen Elizabeth II’s first visit to Australia as reigning monarch in 1954. Accompanied by the Duke of Edinburgh, she inspired unprecedented excitement. As Kate Evans observes, it was a ‘visual event’ before the launch of television. Newspapers carried supplements with hundreds of photographs and commemorative specials.58

It was considered ‘the greatest tour’ until Prince Charles and Princess Diana landed in 1983, though Charles was largely relegated to the pictorial background due to the ‘Diana effect’.59 ‘Everyone just fell in love with her,’ Phelan remembers. ‘You couldn’t take a bad picture of her.’ Princess Diana was the quintessential pin-up. The photographers’ animated recollections revolve around the significance of the tours, the protocols and their photographic approach.

The routines and etiquette were prescriptive. Neville Waller, who covered at least twelve tours, says it was a ‘travelling circus’. ‘You’re very much told what you can and can’t do, where you could and couldn’t stand,’ Lloyd Brown recalls. ‘Everyday, they’d have a running booklet of what was going to happen, and the timing. You weren’t really allowed to ask them to position themselves.’ All the photographers were accredited, and if they strayed from the rules, they would be ‘thrown off the tour’, Barlow explains. They were permitted to meet the royal visitors on the first day after all the formalities and were given warm gins and tonic and some biscuits. There are now very specific instructions regarding media arrangements on the official website of the British Monarchy: taking photographs of people eating or drinking (except during the ‘loyal toast’) is discouraged, and a strict dress code is issued to media representatives.60

For many photographers, it was also the first time they encountered the British media pack, who were, according to Stevens, ‘very competitive’. Wells recalls a bus full of photographers with ‘their fancy cameras and ladders hanging off them’ during a photo op at a mine in Queenstown. ‘With the local guys, they tend to give each other a bit of space; there was none of that here.’ McPhedran observes that the British photographers were more intrusive, and the Australians were more respectful. The tours were ‘hard work’ and involved inordinate waiting, but photographers like Stevens thrived on the rivalry.

The greatest challenge was to get a shot that offered something unique in fairly prosaic settings. For Stevens, it was photographing Princess Diana leaving a train. Magowan’s encounter was more accidental, when as a callow, C-grade photographer, he was sent to Government House for a tree-planting. After taking the requisite shot, Magowan wandered around the grounds to find the Queen sitting on a chair. ‘I took a picture, then I got a tap on the shoulder telling me that I shouldn’t be there and to get lost,’ Magowan recalls. ‘I developed the film, and then realised that’s what the commotion was about; her feet couldn’t touch the ground’.61

9.8 The Queen and Duke of Edinburgh at Government House Perth following a tree planting ceremony, 29 March 1977. Photographer Guy Magowan, published in the West Australian (Guy Magowan).

The near misses, or missed opportunities, dominate their recollections. When covering the 1954 tour for the Daily Telegraph, Barlow was given an old camera with a magazine that held eighteen films. As he walked to his vantage point, he heard a metal noise: the back of the camera had flown open and he’d lost half the film. Only two images survived. Naivety might well have derailed Brown from the Melbourne Age. After taking photographs of the Queen and Prince Phillip in Sydney, a local photographer suggested to Brown that he should go and have a drink before transmitting them. ‘I think I was conned because when I got to the post office, there was a huge line to send pictures. I learned a lesson never to do that again; get rid of the pictures first, then go and have a drink.’ Chambers also learned a valuable lesson after she persuaded Prince Charles’ minder to get him to wear a bushfire helmet for a photo. ‘He put on the helmet and, as I lifted my camera to take the picture, I realised I was on my last frame of film. Everybody got the picture except me.’

The royal tours were stage-managed performances. The Palace and the press have always co-existed symbiotically, spinning stories and photographs to suit their preferred narratives. One of the apparently great ‘gets’ occurred on Perth’s North Cottesloe Beach when Prince Charles emerged from the surf and was kissed by Jane Priest, a model.62 It was later revealed that the kiss was an elaborate royal stunt arranged by photographer Kerry Edwards and the social writer for the Sunday Independent, and consented to by the Palace to make Charles appear more relatable and an irresistible object for a beautiful young woman.63 As Meares reminds us, access is often dependent on the photographers being ‘complicit in the myth-making process’.

Like their interactions with the royals, entertainers were sometimes important career markers in the photographers’ lives. In the words of Alan Porritt, the photographers had ‘a front row seat’. The visual attention given to celebrity escalated after World War II, when international actors and entertainers began to visit Australia with the obligatory photo ops and press conferences, and the diffident but inevitable validation-seeking question, ‘How do you like Australia?’ First came Britain’s acting royalty, the Oliviers, then English and American cast members in Australian films and, later still, singers and bands, including Frank Sinatra, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and ABBA. Particularly coveted were images of celebrities behaving badly, such as Joe Cocker being deported after drug charges in 1972, and the image of Sinatra fleeing a media posse after he referred to female journalists as ‘the broads who work for the press’ and ‘hookers’.64

The singular watershed in many of the older photographers’ recollections was the Beatles’ tour in July 1964, which they covered as young men. It was, according to Brown, ‘much bigger than anything they’d seen here, other than the royal tour’. The photographs of the Beatles’ arrival at Sydney’s Mascot International Airport in the ‘pissing rain’ and the band on the balcony of the Southern Cross Hotel in Melbourne are embedded in the photographers’, and public’s, memory. It was mayhem. Logistically, the tour was difficult, explains Brown, because it wasn’t photographically organised and they had to anticipate the fans (mainly female)65 and the band. Brown got ‘some good shots of them but the better ones were from the roof,’ he says.

9.9 The Beatles wave to fans from the balcony of the Southern Cross Hotel in Melbourne, Victoria, during the Beatles 1964 World Tour, 15 June 1964. Photographer not cited (News Corporation/Newspix).

Photographing entertainers, concerts and music events was a common way of gaining photographic experience and developing a portfolio. Many of the interviewed photographers depicted homegrown and international talent in the 1970s and 1980s, conveying the gritty youth culture of a rebellious new generation. The challenge was to capture the entertainers differently, as Dupont explains: ‘A film premiere with all the photographers lined up with flashes going off … Rather than be in the huddle, why don’t you do an aerial? Find a different way of capturing that event, so that you come out with a photograph that is uniquely yours … It’s an artistic thing, a creative thing, as well as trying to find a different way of seeing.’

With the more frequent arrival of entertainers and a greater emphasis on celebrity in the newspapers, a more troubling photographic practitioner, the paparazzo, emerged. It would be naive to suggest that there were no ruthless newspaper photographers. In the late 1960s and 1970s, as Bill McAuley explains, ‘they would do anything to get the picture. Tell a lie, misrepresent themselves in a different way back then … That sort of disappeared. Then a professional newspaper photographer would go to any lengths to get the image, but there was a line.’66 According to Waller ‘sometimes you might get into trouble from the editor for not taking a picture’.

The most notorious and mythologised Australian example occurred in 1969, when freelance photographer Peter Carrette posed as a doctor and took a grainy photograph of singer Marianne Faithfull as she lay in a coma after a drug overdose in the intensive care unit of Sydney’s St Vincent’s Hospital. A number of Sydney photographers remember that the photograph evoked outrage and a sense of wonder at his audaciousness. McAuley describes it as ‘a line that was definitely crossed’.

Carrette, whom Peter McNamara regards as ‘the first real paparazzi photographer’, remained ambivalent about the experience. The photo, after appearing on page one of the Sydney Sunday Mirror on 13 July 1969, was sold to Europe and the United States for A$18 000. Carrette, who reportedly received A$2000, told journalist John Huxley that he was ‘ripped off shitless’.67

Many photographers speak of their recent encounters with a ruthless new breed of paparazzi who, untethered and opportunistic, pursue their game and the big money. Like citizen photographers who snap celebrities, they do not have to adhere to a code of ethics. ‘It’s open paparazzi war,’ McAuley observes.68 They are ‘dangerous’, Stevens insists; the ‘competition is so fierce that it’s no longer about quality, but about being first’.

The demand has also compromised professional photographers, who are expected to adopt some of the more invasive methods, forcing at least one photographer’s resignation: ‘There’s this emphasis on celebrity and capturing people who don’t want to be photographed. I’ve done it but I’m dead against it, and won’t ever do it again.’ Another photographer, who freelanced early in his career as a celebrity photographer, found it ‘incredibly uncomfortable’, conceding, ‘Every time, I would say, “This is the last time. I don’t want to do this anymore” … I don’t like invading people’s privacy in that way. My idea of photography is to have a 35-mil lens and to be up in someone’s face and be photographing something where that person is acknowledging that you’re there. It’s not stealing. Long lens photography is kind of stealing.’

Celebrity news has always been privileged—Errol Flynn’s rape charges were front-page copy at the height of World War II—but a seismic shift occurred with the internet and, later, social media. Both encourage unmediated visuals from problematic sources, and the sheer amount of coverage just feeds the demand. SMH journalist Jo Casamento writes of the prize scalps, the appeal of reality television personalities, the combined worth of couples, and the fate of those in the ‘bargain basement’.69 Several picture editors acknowledge the frequent use of photographs by ‘paps’ released by online agencies such as INFphoto.com, which ‘specialise in celebrity pictures, and amateurs’.

Certain celebrity women have become favourite marks. Jamie Fawcett, a paparazzo who works for OMGnews.com.au—another Australian supplier of celebrity photographs—has said that if Lara Bingle were to get ‘her boobs out on the beach, that shot would be worth $10,000’.70 Bingle became the contemporary manifestation of the girl in the bikini after her debut as the face of Tourism Australia (a deliberate and explicit coopting of Anglo female identity into the Australian national mythology), later emerging as the ‘WAG’ and even the ‘page three girl’. In 2014, Sydney’s Daily Telegraph published a photo taken by an amateur photographer showing a glimpse of the Duchess of Cambridge’s bare bottom, defying the ‘antiquated code of etiquette’ set by the British media.71

There are even more contentious suppliers. In 2010, Woman’s Day published a four-year-old photograph of Bingle semi-naked. Bingle was in the shower and appeared distressed. It was alleged her footballer boyfriend, Brendan Fevola, had taken the photograph. Woman’s Day editor Fiona Connolly said the publication of the photograph was newsworthy, adding that the magazine did not pay for the image and it had been ‘doing the rounds’ among sportspeople. Most newspapers published the image, and Fairfax printed a story critiquing the ethics and the breach of trust, but it also seemed to be an excuse to feature the photograph.72

Social media have played an important role in contemporary identity-formation.73 Celebrities and the celebrity industry—agents, managers and publicists—have always used a number of strategies to control and manufacture their image.74 They now supply photographs directly to media organisations who feed 24-hour demand, or they share their images with their followers on Instagram and other social media sites. The royal family, for example, bypass legacy media to connect directly with their audience. The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge frequently release family photographs taken by the princess, and professional images are posted online by Kensington Palace’s Twitter and Instagram accounts and then picked up by Australian media outlets.

Olivier Driessens points out that the press and the promotional and publicity industries are structurally embedded into a media economy.75 An example of photographic censorship caused by the conflation of media management and promotional and commercial arrangements became public knowledge in 2015 after singer Jessica Mauboy failed to sing the national anthem at the Melbourne Cup. The Victoria Racing Club objected to Mauboy’s shoes because they were not stocked by the VRC’s sponsor Myer, causing the singer to abandon her appearance. It was then reported that the VRC and Myer had also vetoed the publication of photographs of Hollywood actor Hilary Swank holding the Melbourne Cup, again because of an unsanctioned wardrobe choice. The Herald Sun, as a sponsor of the Melbourne Cup carnival, reportedly ‘agreed to pull the picture at the VRC’s request, leaving the newspaper forced to find a replacement front-page picture’. Another photograph arranged at short notice by the newspaper was then also pulled because the model was wearing an outfit from a rival department store.76

This symbiotic relationship between the VRC, public relations and news photography had its origins exactly fifty years before, in 1965, when British model Jean Shrimpton became the first celebrity to be brought to Melbourne to ‘kick interest’ in the racing season. The VRC and Orlon, a local synthetic fibre company, sponsored her two-week promotional visit to Australia. Sun News-Pictorial photographer Ray Cranbourne’s now celebrated, but then scandalous image of Shrimpton wearing a mini-skirt five inches above her knee and bare arms, with no stockings, gloves or hat, attracted the requisite attention. The photograph, taken on Derby Day, captured Shrimpton’s beauty and movement, and the surrounding women’s disapproving and delighted expressions. Youth culture was about to explode.

As well as unleashing the paparazzi and thereby devaluing press photography, a narcissistic celebrity culture has increasingly driven the news enterprise, leading contemporary news audiences to invest even further in the minutia and vacuousness of celebrity, particularly female celebrity. As John Hartley notes, ‘we are in a period of demand-led rather than supply-led journalism’.77 The consequences of this become apparent when surveying Australian newspapers. As Jason Stanley finds in his US study of women’s absence from news photography, diverging newspaper strategies have meant the press have more generally replaced hard news with articles focusing on entertainment, celebrity, fashion and lifestyle, in which photographs of women often appear.78 This equally applies to Australian press photography.

Even when deserving of hard-news treatment, images of women are still often consigned to the women’s section or softer news.79 The Australian narrative is still orientated towards fixed notions of Australian gendered identity and towards stereotypes of beauty, success, victimhood and crisis.