FAY ANDERSON

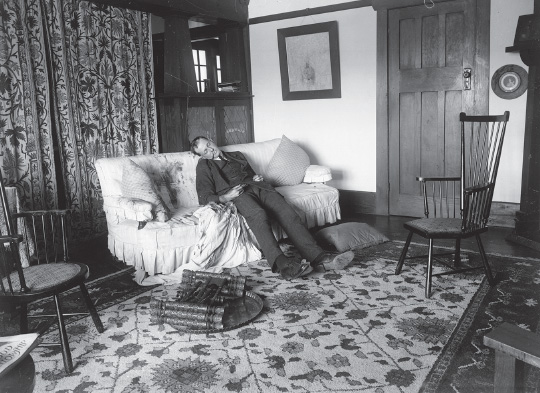

ON 15 MARCH 1921, Sydney’s Daily Telegraph published a photograph of Claude Tozer slumped on a sofa in an immaculate drawing room. His patient Dorothy Mort had shot him once in the chest and twice in the head. According to reports, Mort was ‘a strangely neurotic and passionate’ woman who had had an affair with the ‘dashing’ young state cricketer and medical practitioner, and had murdered him when he attempted to break off their relationship. Police, journalists and several photographers who attended the crime scene found Tozer downstairs and Mort bleeding in a bedroom from a self-inflicted bullet wound to her chest.1 The photograph of Tozer remains one of the most graphic crime images published in an Australian newspaper.

In 1927 the Australian Journalists Association (AJA) revisited the Telegraph’s decision to print the photograph and called for a policy of keeping newspapers free from ‘anything likely to excite horror’.2 It was a vain request. Despite protestations, the press and public have always been fascinated with crime, violence and the macabre. ‘It’s part of the Australian culture. It goes back to Ned Kelly,’ Darren Tindale observes. JW Lindt’s photograph of the dead body of Kelly gang member Joe Byrne captured the sensationalist allure and also the contested debate about the first published photograph associated with a criminal case.3

The visual representation of crime dominates our newspapers. At the same time, criminal cases are so ubiquitous that they are often consigned to inside the paper unless they conform to certain news values or provide a narrative to keep alive the story.4 The murder of nine-year-old Mary Hattam in 1958, for example, appeared only briefly in some newspapers. The case became national front-page news after Rupert ‘Max’ Stuart, an Indigenous fairground worker, was convicted of murder and sentenced to death. It has remained one of the ‘most discussed criminal cases in South Australian history’ due to the intervention of Rupert Murdoch, proprietor of the afternoon daily the Adelaide News.5 Murdoch supported the campaign of his editor, Rohan Rivett, who used the newspaper to raise doubts about the trial. Amid allegations of a coerced confession, Rivett advocated for a royal commission into the conviction, his activism ultimately saving Stuart from the gallows.

10.1 Scene of the shooting murder of Dr Claude Tozer, at the home of Dorothy Mort, Lindfield, NSW, 21 December 1920. Photographer not cited, published Daily Telegraph, 15 March 1921, page 6 (NSW Police Forensic Photography Archive, Justice and Police Museum/Sydney Living Museums).

Newspapers employ motifs and narrow narratives when covering criminal cases: images of the arrest, the crime scene, the victim, their family and friends, witnesses, the perpetrator, the arrest, court appearances and the aftermath. There are important photographic rituals surrounding the visual representation of violent crime that inform our understanding of criminality, celebrity, gender, ethics and Australian identity. These traditions and routines will be the focus of this chapter.

Most of the interviewed photographers remember crime stories with vivid clarity but are rarely nostalgic. Deemed the least favoured assignment, criminal cases were ‘particularly hard to cover’.6 Very occasionally, they suppressed their memories. Rick Stevens, who began his career in 1961, cannot recall covering Snowtown, a depraved series of twelve murders involving a marginalised underclass: ‘It was so ghastly, I actually forgot about it. I didn’t get involved. I couldn’t get involved.’ Photographers mediated their emotions while engaging with the police and vulnerable or aggressive people, as well as demanding editors. ‘There were a lot of devastating jobs,’ Angela Wylie says, but ‘you build up a way of dealing with them’.

Photographers, like journalists, cover crime during police rounds or when assigned to breaking or ongoing stories. Unlike photographers in the United States and United Kingdom,7 Australians have rarely specialised; they have always been expected to do ‘everything’. As a number of photographers pragmatically explain, crime is simply ‘part of the day’s work’. No matter how senior, all are assigned to criminal cases, even the most mundane court appearances.

Police rounds were a seminal apprenticeship. There was always ‘something exciting going on,’ Neville Waller remembers. As an ACP copy boy in 1960, he listened to the police radio and frantically went through the folders of all their contacts. The ‘ambos and coppers’ provided crucial tips. Waller followed the countless prison escapees and bank robberies and the high-profile kidnapping of eight-year-old Graeme Thorne on his way to school on 7 July 1960. The first recorded ransom demand in Australia was sent to Graeme’s father, who had appeared (with the family’s Bondi address printed) in Australian newspapers after winning £100 000 in the Opera House Lottery a month before. Graeme’s body was found on a vacant block over a month later.

Lloyd Brown, who worked at the HWT for forty-seven years, recalls that ‘you could get quite close’ to the police during the rounds. From the 1950s, the Melbourne Herald’s photographers and journalists worked out of police headquarters when they were on police rounds. That stopped, Clyde Hyde, a former HWT photographer, says, ‘when somebody decided to blow the building up’. The homicide police continued to be a fixture at the Herald’s Christmas parties. Stevens elaborates on the dynamics of the police round: ‘Most of it was spent hanging outside pubs really, waiting to get the journalist out of the pub … The police drank, photographers drank, journalists drank … The more you drank, the more information you got, and the drunker they got, the more information they released.’

Before communications moved from analogue to digital, police radios were rigged to press cars, and it was common on the round for a journalist, photographer and driver to spend an entire shift in the car ‘just waiting’ for something to happen. In 1923, the Victoria Police became the first force in the world to use wireless communication in cars. During periods when domestic assault and violence spiked (public holidays and Sunday nights were particularly notorious), the photographers didn’t need to wait. Brown covered three separate murders on Christmas Day in 1949; his wife came along to keep him company.

The symbiotic relationship between journalists, press photographers and the police was established during police rounds, at crime scenes and, as Stevens observes, frequently in pubs. It was also based on mutual trust and discretion; the police were regarded by the press as excellent sources and as a means of gaining access. Familiarity was not only confined to the police. Hyde explains that crime photography was dependent on a good relationship ‘with both sides of the law’. As Lyndon Mechielsen explains, people rarely leaked information for altruistic reasons but because they might hate someone, want to distort the news process or want a particular end result; sometimes the leaker was just too intimate with the police journo. Closeness with police and other insiders promised exclusivity but could compromise reporting.

This relationship was central to the media’s depiction of the disappearance of nine-month-old Azaria Chamberlain from a tent at a camping ground at Uluru on 17 August 1980, which resulted in the wrongful murder conviction of her mother, Lindy Chamberlain, and a suspended sentence for Azaria’s father, Michael, for being an accessory after the fact.

The tragedy extended over three decades and included three coronial inquests, a seven-week trial and Chamberlain’s guilty verdict, two appeals, Chamberlain’s release in 1986, and an eleven-month royal commission, which ultimately exonerated the couple in 1987. The case culminated on 12 June 2012, when the Northern Territory coroner, Elizabeth Morris, announced that the cause of Azaria’s death was ‘the result of being attacked and taken by a dingo’.8

It would prove to be one of the most photographed cases in Australia’s history. Many commentators argue that an increasingly hostile media (and journalists working in collusion with the police) effectively tried Chamberlain by demonising the family and destroying any possibility of a fair trial through a slew of apocryphal stories.9 Mechielsen, who was then a NT News photographer, believes his newspaper ‘probably thought she was guilty and probably pushed that line. It was pretty conservative up there.’ The photographers’ interaction was more complex. Russell McPhedran covered the case from ‘day one’ for Fairfax and became friends with the family. ‘I thought she was guilty at the start because we spent most of our time with the police. Journalists are always with the police because that’s how they get their information,’ McPhedran recalls. ‘They thought she was guilty and I thought she was guilty. I then spent time with her and thought, no she wasn’t.’

Mutually beneficial relationships also extend beyond the police. The relationship between the media and the authorities was particularly transparent in 1986 when the NT News ‘got the drop’ that Chamberlain was going to be released, sending Mechielsen to Berrimah Prison. Apparently, the News had some sort of ‘yarn’ about the government of the day that was ‘smart enough to realise that if it signed off on that particular day and leaked it, that was going to subsume the news for the next number of weeks’. Mechielsen says ‘it was one of those classic cases of politicians using the timing to distort the news process and not come under scrutiny … when they should have … It was a really interesting time.’10

Asked whether personal opinions and official intervention influenced photographers, Waller replies that it should not affect your work. But it was not always easy to stay objective, as one photographer concedes. He chose not to photograph someone he thought was innocent but would ‘go flat out to photograph a fellow that [sic] was a murderer or a sex assaulter … I’d get his bloody picture; if I could help justice, I certainly would.’

Photographs of arrests also resulted from police tip-offs. The image of Leslie ‘Squizzy’ Taylor’s ‘surrender’ filled the front page of the Sun News-Pictorial on 22 September 1922. Ray Blackburn, a longstanding picture editor for the Age, was alerted to Ronald Ryan’s return to Melbourne in 1966. Ryan and Peter John Walker had escaped from Pentridge Prison in December 1965 when Ryan seized a rifle and shot dead a prison officer, George Hodson. Ryan was the last man executed in Australia.

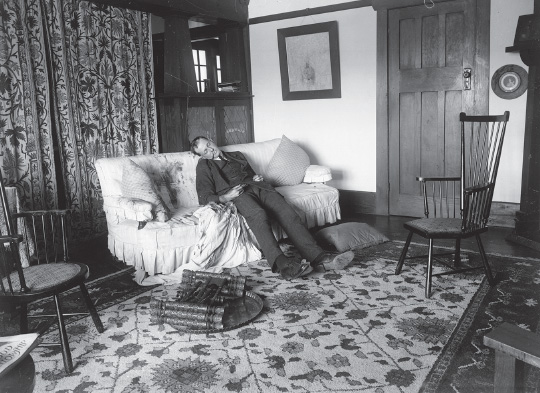

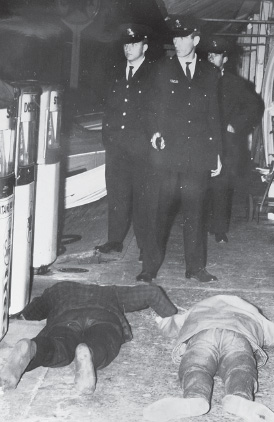

Peter McNamara’s photograph of two suspects arrested for the ‘Bobbin Heads double murders’, the killing of Police Sergeant Adam Schell and night watchman Frederick Marshall in 1968, also resulted from leaked information. McNamara, who had begun his cadetship at the Daily Mirror four years earlier, remembers a cryptic ‘call’ that a policeman was down. The police in attendance were later disciplined because senior police wrongly assumed they were posing for McNamara. As Susan Sontag argues, ‘one never understands anything from a photograph’ without context.11 Several photographers conceded that their presence protected a suspect from being beaten up or even shot by the attending police.

10.2 Two suspects arrested for the Bobbin Heads double murders, 1968. Photographer Peter McNamara, published in the Daily Mirror (Peter McNamara/Newspix).

Sometimes a photographer stumbles upon an arrest. Wylie noticed police arresting a man when she took a detour along Beaconsfield Parade in Melbourne on her way to work in 2004. She didn’t recognise Carl Williams, the leading figure of Melbourne’s gangland murders, but thought she should stop. ‘I casually got out of the car and took about ten photos. I was the only photographer there,’ Wylie recalls. ‘There’s nothing really beautiful about that photo, but it tells a story.’ Wylie is modest: her deft speed and instinct captured a portly Williams, handcuffed and surrounded by three detectives, his expression betraying hubris and contempt.12

More surprisingly, until the 1990s, the police regularly asked news photographers to photograph suspects, to provide crime scene prints for trials or even to take police photographs when their photographic unit was not on hand. At other times, photographers accompanied the police on Friday and Saturday nights to ‘shoot pictures’ of murders and road accidents for the coroner’s court. This conflating of newspaper photographs and police images was fraught. Grim crime scene photographs like Tozer’s were never intended for newspapers or for public dissemination. The police photographer, as Helen Garner notes in her essay on writing about darkness, is immune to ideas of art.13 Crime news photography is also supposed to record, but with some rhetorical enrichment.

10.3 Police arrest Carl Williams, a major suspect in Melbourne’s gangland war, in Port Melbourne, Victoria, 17 November 2003. Photographer Angela Wylie (Angela Wylie/Fairfax Syndication).

The merging of roles was sometimes a rite of passage. The unusual closeness to death and the more clinical aspects of forensic photography made an impression on all the interviewees who moonlighted as police photographers. ‘That was something that stuck with me for years: when you see people blown apart with a shotgun or beheaded in road accidents’, Bruce Postle admits.14 McPhedran elaborates: ‘Some guy had stabbed his girlfriend to death and then himself. A policeman came out of the house and said, “Hey son, come here. The police photographer has been held up. Would you like to take some pictures for the police—not for your newspaper—just the police?” I said, “Yeah, yeah,” anything to get in there. I went in and it was barely light. The police doctor was there and told me to take one from this angle, and my eyes were just getting adjusted to the light. All I could see was the girl on the bed and he was lying on top of her, still alive and still holding the knife. There was blood all over … Then the doctor said, “Now we’ll have one here.” I said, “No you won’t. I have to get out of here.”’

The press also photographed murder re-enactments for police. A chilling image from 1963 shows Eric Cooke, who confessed to murdering eight people, pointing to the spot where he ran down and killed one of his victims, Rosemary Anderson. Despite Cooke’s testimony and the photographic evidence, the court did not find his confession credible. Anderson’s nineteen-year-old boyfriend, John Button, served five years for manslaughter, having been intimidated into confessing during a 22-hour police interrogation. His conviction was not quashed until 2002, after new evidence came to light corroborating Cooke’s confession. Another young man wrongly convicted of one of Cooke’s murders, Darryl Beamish, only narrowly escaped the death penalty and served fifteen years in prison for the crime, which he didn’t commit. Beamish features in a celebrated photograph taken by Barry Baker at the moment his conviction was overturned in 2005.15

10.4 Eric Cooke, who murdered eight people and terrorised Perth, pointing to the spot where he ran down and killed Rosemary Anderson, 11 September 1963. Photographer not cited, published in the West Australian (News Corporation Australia/Newspix).

The dynamics have changed since the 1990s due to police occupational health and safety, forensic integrity, media advisers and a social media presence. Renee Nowytarger observes that while crime cases still play a prominent role in newspapers, photographers are ‘held quite a fair way back’. Tip-offs are now forbidden, but unofficially they still occur. In 2014, a police officer was investigated for disclosing confidential information to a journalist about footballer Ben Cousins’ court appearance over reckless driving.16 These relationships, dynamics and reporting routines guarantee photographers’ access to crime scenes and influence what is seen in newspapers.

One of the most compelling photographic genres attached to crime, and one that does not directly involve newspaper photographers, is the mugshot. The Australian press has published mugshots since the 1920s, but their history as criminal identification dates back to 1888, when Alphonse Bertillon, a French police officer and biometrics researcher, standardised the process, leading police to compile mugshot photo books.17 American photographer and theorist Alan Sekula argues that police archives were utilised repressively to prove identity, as evidence of recidivism and as a method of criminal classification.18

Garner suggests that mugshots ‘are wonderful evocations of period and of class—precious historical documents’.19 As the mugshots of Great Britain’s Moors murderers—Myra Hindley and Ian Bradley—show, they can become iconic. In particular, Hindley’s mugshot, with her peroxide blonde hair and expression of menacing defiance, continues to epitomise pure feminine evil.20

On 7 November 1949, Jean Lee seduced William ‘Pop’ Kent, a 73-year-old, part-time bookmaker, in a ploy with accomplices Robert Clayton and Norman Andrews to rob him. She accompanied him to a grim boarding house in Carlton, where she was joined by Clayton and Andrews, and they beat, tortured and strangled Kent. Like Hindley, the most severe approbation in this case was reserved for Jean Lee rather than her co-accused. In 1951, Clayton and Andrews were executed, and Lee was the first woman to be hanged in over fifty years, and the last woman hanged in Australia.

10.5 Mugshot of Jean Lee, ‘To Be Hanged’, Barrier Miner, 14 December 1950, page 1. Photographer not cited (National Library of Australia).

As a sex worker and single mother, Lee was the antithesis of social and moral respectability in the early 1950s. In the wake of World War II, newspapers reflected a repressive conservatism and anxiety about women’s status, policing their sexual behaviour.21 Though photography was finally becoming a separate and compelling feature of Australian newspaper journalism, and had ceased to be subsidiary and unevenly integrated, as it had been during the 1940s, it is striking how little visual coverage was given to the murder of William Kent in Melbourne. Both the print and visual coverage of Lee presented a moral and cautionary tale about sex, promiscuity and greed. The dominant representation of Lee was restricted to only six photographs, including four mugshots. The reliance on these mugshots was intended to symbolise her criminality and her moral and physical decline. Unlike her two co-accused, Jean Lee was the pictorial focus.

Mugshots were not always used to denote criminality. Rather than symbolising guilt, Ronald Ryan’s mugshot is now used as a commentary on the change in attitudes to capital punishment. And in exceptional cases, mugshots are published for their comedic potential, most notably in the case of Tony Mokbel, the balding, convicted drug dealer who skipped bail and was arrested in Greece sporting an ill-fitted toupee.

In almost every high-profile crime story, newspapers publish a crime scene image. The crime scene is the visual and symbolic space, and its representation can take a number of forms. As Kate Evans notes, the first common form often includes markers: bloodstains, a chalk drawing, a dotted line conveying the chain of events and action, an empty room or driveway. Often, the chalked space a victim inhabited or an area marked out by, and for, forensic examination is also photographed or created.22 Crime photographs do not show the act. They have a different meaning and currency.23

Crime scene images play an important role: they emphasise the loss of life and provide a clear trajectory of events when photographers have not had immediate access to the crime itself. Meticulous diagrams of all the relevant sites (accompanied by chalked outlines where bodies had fallen) were part of the coverage of mass shootings at Port Arthur, Walsh Street, Hoddle Street, Queen Street and the Strathfield Plaza, as well as the Russell Street bombing.

If the bodies are never found—or, in the case of Lindy Chamberlain, no crime was committed—then the site is still marked, but the trajectory is often speculative, signifying the victim’s possible movements. Diagrams accompanied reports on the disappearance of the Beaumont children from Glenelg beach in 1965 and are still included whenever the case is revisited. The police are often photographed searching for clues or gathering evidence. The image of Les Ratcliffe being comforted by Senior Inspector CE Lehmann during the search for his eleven-year-old daughter Joanne, who was abducted along with four-year-old Kirste Gordon from the Adelaide Oval on 25 August 1973, is both intrusive and distressing. The children were never found.

10.6 Senior Inspector CE Lehmann comforts Joanne Ratcliffe’s father Mr Les Ratcliffe during the search for his daughter. Photographer not cited, Adelaide Advertiser, 27 August 1973, page 1 (News Corporation Australia/Newspix).

As ‘a crime scene’, Uluru formed a tangible and ‘imaginative backdrop’ to the Chamberlains’ ordeal.24 Scandalous rumours swirled around the Chamberlain family, suggesting that the name ‘Azaria’ meant sacrifice in the wilderness and reinforcing the significance of the outback in public perceptions of the case. But while the area offered drama for journalists (and opportunities to fictionalise), it was a source of great frustration for photographers. ‘It was a terrible job. Nothing was happening. We were kept behind a police line, and we just stared at the Rock all day. It was as hot as Hades,’ Bryan Charlton, a photographer from the Adelaide Advertiser, recalls. ‘It was not great for pictures.’25

The photographs reflected the limited access given to photographers during the trial, the visual importance of both Lindy Chamberlain and Uluru, and various logistical problems. Again, Charlton provides the context: ‘I had to send my film back to Adelaide each day on a light aircraft that would travel between Ayers Rock and Alice Springs. To make sure the film got to its destination, I would tear a twenty-dollar bill in half and tell the person taking the film that they’d get the other half when the film got to Adelaide. You had to make sure the parcel wouldn’t get left behind or overlooked.’26

The unpublished images (including figure 10.7) also reveal the intense interest in the case, the heat and the informality. Hyde bluntly explains the appeal of the outback. ‘I used to say, every eighteen months to three years, there is an international story in Darwin. The murder stories in Darwin are amazing, particularly in the eighties. The nineties were pretty boring, but they did a little bit in the 2000s, like chucking prostitutes off the bridge into crocodile-infested waters. Even small towns down south don’t seem to have that.’

10.7 Photographers at the Chamberlain trial. Reporters and TV news crew photographers shown include Ian Mainsbridge (News Ltd), Peter Watkins (Adelaide Advertiser) and Russell McPhedran (Sydney Sun/Sydney Morning Herald). This picture was taken in the searing heat outside Berrimah Prison in Darwin, November 1982, by a remote-control camera on timer by Russell McPhedran (Russell McPhedran).

Peter Falconio’s murder and the abduction of his girlfriend, Joanne Lees, by Bradley Murdoch in 2001 ignited further debate about the media’s sensationalist treatment of a telegenic young woman and the emotional resonance of the outback.27

More recent media such as online video and interactive galleries provide even greater opportunities to display the crime scene or, according to some critics, to exploit the victim and their family. In the emotionally charged case of Jill Meagher, who was raped and murdered by Adrian Bayley in Melbourne in 2012, the police evidence book, which contained images from the crime scenes—including the contents of Meagher’s handbag, retrieved from a laneway—featured in online slideshow galleries. The thirty-eight photographs, including ‘an ABC-branded pencil found at the scene of Jill Meagher’s rape and alleged murder’, were sourced from Victoria Police.28 Closed-circuit television footage showing Bayley lurking near a shop on Sydney Road was posted on all press news sites.

A second common form of crime scene image shows the crime scene without markers, and is often produced when photographers are able to gain closer access. Buildings often assume central importance in notable cases, including the Sydney Hilton hotel (which was bombed in 1978), the Whiskey Au Go Go nightclub (firebombed in 1972), the Childers Backpacker Hostel (where fifteen backpackers were burned to death in 2000), and Snowtown.

The disused bank vault where eight dismembered bodies were discovered in six barrels has stigmatised the small farming community of Snowtown in South Australia. Charlton and Chris Mangan were the first photographers granted access to the cleared vault after the police held a press conference. Stevens was dispatched from Sydney to photograph a number of other relevant sites in the North of Adelaide. ‘I remember going into a house and thought, this is the filthiest house I’ve ever been into … and the carpet was stained where people had been sitting and just watching television all day … Pictorially it was challenging,’ Stevens explains. ‘There wasn’t that much to photograph because it had all happened.’ Aside from the sinister bank vault, other images show police digging up various suburban backyards looking for bodies, and photographs of friends of the victims or suspects.

Photographs of crime scenes can also convey heartbreaking loss. Two important sites have defined the massacre at the historic Port Arthur penal colony in Tasmania on 28 April 1996, when Martin Bryant murdered thirty-five people and seriously wounded another twenty-five. The first is the Broad Arrow Café, where Bryant indiscriminately shot tourists and staff, killing twelve and injuring another ten within fifteen seconds. The second site of immense symbolism is a stringybark tree where Bryant executed Nanette Mikac and her daughters, three-year-old Madeline and six-year-old Alannah.

Eight years earlier, the murder of two young police constables, Steven Tynan and Damian Eyre, on Walsh Street, South Yarra, in Victoria had conjured up similar feelings of horror. Several photographs of the crime scene were published, conveying the premeditation of the murders.29 The first was an overhead image of the stolen Holden Commodore used by the killers to entice the police. The other photograph shows both the abandoned car and the police car, the driver’s door open where Constable Eyre had struggled with one of the attackers before he was executed. Four suspects stood trial but none was convicted of the murders.

The coverage of another police shooting differed in its composition and provoked greater controversy. In 1998, Bandali Debs and Jason Roberts murdered two police officers, Gary Silk and Rodney Miller. Michael Gawenda, the editor of the Age, published Jason South’s distant image of Gary Silk’s concealed body, a pool of his blood visible in the colour image. After a story conference, the editorial team agreed that the photo appropriately conveyed the malevolence of the murders. South elaborates on the ensuing uproar after the photograph was ‘splashed across the front page’: ‘It was a story that deserved that kind of treatment. It would’ve been distressing for their families, but they are a different kind of job. I was comfortable with those pictures running … The police union took the discrepancy to the Press Council and the Herald Sun jumped on the bandwagon and said they would never have run it. I don’t know the ethics of whether I should be shooting a dead body in Melbourne, but I’ll shoot it and we’ll debate it afterwards. People higher up the food chain make those decisions.’

On the same day, the Age and other newspapers published a series of graphic photographs of the car bombing in the market in Omagh, Northern Ireland, where twenty-nine people were killed and another 220 injured. In the letters to the editor, the photographs, showing body parts and uncovered corpses, did not provoke the same level of fury as the photograph of Silk.30

‘If it bleeds, it leads’ is a truism and a cliché, but it is more complicated in the Australian context. Mike Bowers explains that you could get away with a lot more in black and white than you could with colour. ‘There are unwritten rules and you usually can’t publish blood or dead bodies. It also depends on the identity of the dead body,’ Bowers maintains.

The Police Union complained to the Australian Press Council that the photograph invaded the privacy of Gary Silk and offended the sensibilities of those close to him. The photograph of Silk had, according to the Police Commissioner, exacerbated the overwhelming anguish already being felt in the wake of the policeman’s death. In response, the Age representatives said they ‘deliberately took the decision to publish the photo because it was a shocking event’ and furnished the council with images of bodies in other Australian and overseas newspapers, arguing that ‘these were equally shocking and demonstrated that such photographs were commonly used in modern newspapers where “the use of photographs is as important as words”’.31

The Press Council conceded that the publication of pictures of dead bodies presented them with ‘difficulties’ and they ‘adopted a general approach that there is a difference between photographs of the unidentified victims of foreign carnage and a front page picture of a body in a local community where a victim is well-known’. The council agreed that it was a ‘horrific crime’ and its enormity was ‘graphically reinforced by the picture’. On the other hand, the colour photograph used displayed the dead man’s blood loss in a manner that could not help but distress those who were close to the deceased. On balance, though, it was ruled that the Age’s ‘decision to publish was in the public interest and therefore did not breach its principles’.32

The ethical considerations surrounding the publication of images of the dead and the notion of public interest are complex. In 1938, the AJA demanded that no photographs of ‘local corpses’ should be published.33 In the Media Entertainment & Arts Alliance’s code of ethics, the AJA’s successor stipulates that journalists should ‘respect private grief and personal privacy. Journalists have the right to resist compulsion to intrude.’34 The standard is vague and subject to interpretation. There are also no guidelines about images of tragedy or horror. As historian John Taylor observes, the press usually err on the side of caution. The editing of horror is not necessarily a conspiracy of censorship, nor is its publication always gratuitous.35 The ethics have been further complicated by the internet, which allows for more graphic visuals and has removed editorial gatekeeping. ‘The internet doesn’t really have a filter,’ observes Craig Borrow.

Photographers admit that their impulse is ‘to take the picture’, while the decision to publish graphic imagery is the province of the editor. Tindale says, ‘There’s no rule. It’s picture by picture, story by story.’ Alan Porritt agrees that ‘it’s an editorial decision’. If you didn’t heed editorial advice, Steve Grove observes, ‘you’d be back doing cheque presentations’. Others lost their jobs when they ignored their editors.

Much has been written about photographing death, and the debates often revolve around whether images of violence are exploitative or didactic.36 Susan Sontag argues that audiences become desensitised to photographs of suffering with repeated viewing.37 Susie Linfield, a journalist and critic, is troubled by the distrust of photography and the way Sontag positions it as treacherous and reductive. Many photographers dispute the idea that photographs of crime are necessarily voyeuristic, though they admit some are. They agree with Linfield that viewing such photographs is an ethically and politically necessary act, connecting us to our modern history of violence and revealing our capacity for cruelty.38 We need to look at uncomfortable images.

The media are more likely to show the dead bodies of those who are considered less worthy of deferential treatment. Most newspapers, including all the Melbourne dailies, for example, published an image of Frank Vitkovic’s body in 1987 after he threw himself from the Australia Post building in Melbourne, having shot eight office workers in a Queen Street building. Bill McAuley from the Australian ‘ran in with the cops, with everyone else running in the opposite direction’.39 Ray Kennedy from the Age took photographs from the street.

10.8 Queen Street shooting: the 22-year-old gunman lies dead on the footpath after throwing himself from the Australia Post building. Photographer Ray Kennedy, published in the Age, 9 December 1987 (Ray Kennedy/Fairfax Syndication).

Julian Kingma, who was only a second-year cadet for the Herald, was the paper’s first photographer on the scene, and his first image was also of Vitkovic on the road. ‘For a photographer who wanted to be a genteel portrait photographer, it was really confronting,’ Kingma concedes. ‘There was so much adrenaline at the time; you didn’t have much time to think about it except for what people had taught me up to that point. You just had to take pictures and respond.’ Kingma’s picture ran on the front page of the Sun. ‘It was my first front page and the scenario was really foreign to me, of a body and bullets on the ground,’ says Kingma. ‘Amongst that morbidness, I was proud that I got page one out of a terrible circumstance.’ Kingma’s ambivalence reflects the pressure on photographers and the hierarchy surrounding publishing decisions. The visual coverage of both Queen Street and the earlier Hoddle Street massacre, where images of the victims’ bodies were published, provoked outrage and was described as ghoulish, sensational, and irresponsible in letters to the editor.40

Since the ‘hoodlum’ Squizzy Taylor terrorised Melbourne in the 1920s, criminal identities have featured prominently in newspapers. Initially inspired by louche newspaper and cinematic representations of American gangsters, press photographs have defined the ‘celebrity’ criminal in Australian life. Their deaths, however, continue to attract inconsistent treatment.

Warren Lanfranchi, a drug dealer, standover man and murder suspect, was shot dead by infamous Detective Sergeant Roger Rogerson in Sydney in 1981. The photograph of his body, lying in a gutter, was widely published. Lanfranchi’s girlfriend, Sallie-Anne Huckstepp, accused Rogerson of murdering Lanfranchi and lobbied the media about police corruption. The media’s treatment of Huckstepp’s subsequent murder in Centennial Park in 1986 was gratuitous. Labelled ‘the girl who knew too much’, she was repeatedly identified as a sex worker and drug addict. Accompanied by an image of her dead and only partially covered body, the Daily Telegraph’s report did not even bother to name Huckstepp, instead captioning the photo ‘Lanfranchi lover’s body found in lake’.41

The Melbourne underworld killings between 1998 and 2010 were a circulation bonanza and involved the murders of thirty-six criminal figures. The news photographs both enthralled and repelled. The most public murder occurred at a children’s ‘Auskick’ football clinic, where Jason Moran and Pasquale Barbaro were gunned down in a car with four children sitting in the back seat. Rowland Legg, the senior sergeant on call, matter-of-factly described the scene inside Moran’s van as ‘messy’.42 Most newspapers carried images of the empty car and the equally dramatic photograph of Moran’s mother, Judy, slumped and weeping at the crime scene.

Photographs of ostentatious underworld funerals showed familiar faces adorned with dark glasses revelling in the photographic attention. Borrow photographed ‘nearly every funeral. These characters, they love it. They think they’re in a movie, a Godfather movie. Kissing either cheek,’ Borrow remembers. ‘You’d look at them and take their photograph and three weeks later you’d be at their funeral. They’re playing games but they’re playing games for keeps.’

Equally important to the public, and to newspaper circulation, are images of the accused being led to and from court. This performance is culturally significant, providing a reassuring vindication of law and order. There is also a stylistic continuity to this imagery. The photo of the court appearance remains visually unchanged: Jean Lee being accompanied by detectives into the watch house before being charged with the murder of William Kent in 1949; Eric Cooke leering at the waiting press throng in 1963; and Ivan Milat, who was charged with the murder of seven backpackers, smirking for the waiting cameras on the way to court in 1994.

It is called ‘parading’, Terry Phelan explains. Phelan covered the Hoddle Street massacre for the duration of a cold Sunday night in 1987, when Julian Knight killed seven people and injured another nineteen. Phelan scrambled back to the Melbourne magistrates’ court, where the police walked ‘their trophy down Russell Street’ as the media throng photographed Knight, ‘a skinny little bloke with a serious gun belt around his waist’.

In notorious cases, if the suspect is not paraded, newspapers rush to print the ‘first picture’ of the suspect from other sources,43 falsely implying that their face might provide a clue to their motives. Martin Bryant’s photograph was splashed on every front page. ‘This is the man,’ trumpeted the Mercury.44 Miranda Devine, a News Limited columnist, expressed disappointment that there were no answers in Bryan’s ‘blank eyes’.45 According to Geoff Turner, the Australian also manipulated an image of Bryant to lighten the eye area, making him look ‘deranged’, which the paper said was not intentional. The picture dominated the paper’s front page under the heading ‘FACE OF A KILLER’, with the drop-head ‘Violent loner spooked locals’. The newspaper apologised to its readers on the following day.46 The acquisition of the image was equally controversial and it remains in doubt whether a journalist broke into Bryant’s home, or was let in by police.47

Certain factors shape press interest: the deployment of the press in institutional settings such as the courts, the need to produce stories to fit news production schedules, news values, and editorial judgements about the appeal of a story and public interest.48 As Yvonne Jewkes observes, any offence (or alleged offence)—particularly one that deviates from the moral consensus—is made eminently more newsworthy if children are involved. This is true regardless of whether the children at the centre of the story are victims or offenders.49 The media descend during the initial crime and return if an offender is put on trial. They remain transfixed, particularly when the case offers longevity or there are doubts surrounding justice.

One of the earliest and most sensational examples was the ‘Gun Alley Murder’, which coincided with the ascent of pictorial daily newspapers, particularly the Sun News-Pictorial. On 31 December 1921, twelve-year-old Alma Tirtschke was raped, strangled and dumped in a Melbourne laneway. According to historians John Lack and Kevin Morgan, the press inflamed public outrage, pressured police for an arrest and matched the government’s initial reward. Although the suspect, Colin Ross, had an alibi, dubious scientific evidence and testimony compromised his trial. In addition, the Herald prejudiced the verdict by publishing Ross’ photograph and printing the names and addresses of the jury.50 Ross was found guilty and executed, then posthumously pardoned by the Victorian state government on the basis of new scientific evidence in 2008.51

Penny Stephens recalls the first time she encountered the media pack. In June 1997, she was sent by the Age to Moe in Gippsland. A one-year-old boy, Jaidyn Leskie, had gone missing in the economically disadvantaged community, provoking speculation about Jaidyn’s mother’s boyfriend and babysitter, Greg Domaszewicz, who would later become the prime suspect. Stephens found the scrum confronting and ‘repulsive’. ‘Suddenly there’d be a hint of a rumour that one of the parties that we needed to photograph was somewhere. Everybody would drive off, and you’d all chase each other. It was just crazy,’ she says. Jaidyn’s body was found in a dam over six months later.

Jay Town, a News Limited photographer, spent two weeks in Moe during Domaszewicz’s committal hearing, which he describes as ‘just phenomenal’ and ‘ridiculous’. Town recalls the intrigue surrounding a pig’s head that was thrown through the window of Domaszewicz’s house (where the little boy had stayed on the night he disappeared) and the complicated sexual histories of many people in the case. ‘The worst part about this is some poor little kid’s lost his life over it. And instead we’re all worried about this theatre in Moe,’ Town says.

Some cases, like Jaidyn Leskie and the 2015 discovery of Khandalyce Pearce-Stevenson’s remains in a suitcase on the side of a highway in South Australia, capture the media’s and public’s imagination. The fact that the body of Khandalyce’s mother, Karlie Pearce-Stevenson, had been discovered in Belanglo State Forest five years earlier only intensified the controversy and tragedy.

The fascination with cases such as these is compounded by the archetypal narrative of the lost child, which haunts the Australian imagination.52 The most famous example of this narrative is the Chamberlain case, which was, as Mechielsen says, ‘a phenomenon’. Photographers still remember the excitement, even revelry, surrounding the trial, along with the key sites of importance. ‘The newspaper office was in Mitchell Street, with the police station right next door, the courthouse over the road, and the Darwin Hotel [and pub] over the road from that,’ Hyde recalls. ‘Alan “Spider” Funnel would base himself at the Darwin Hotel; his bathtub was full of green cans. We all looked after each other, and it was long stints those blokes were sent up for. We played up; it must’ve cost them a fortune. The Chamberlain stuff was fascinating.’

The main reason for the persistent media attention was Lindy Chamberlain herself. ‘People had a direct response to her,’ Mechielsen explains. ‘It was a deep emotional response.’ Chamberlain became the most photographed woman in the country, and her appearance became a public obsession. Women suspected of murder are subjected to intense scrutiny regarding their physical appearance and attractiveness, explains Jewkes. The media value particular aspects of femininity—youth, slenderness, decorativeness—which are constructed to suit the ‘male gaze’.53

The headlines rather than the photographs vilified Chamberlain, reflecting editorial positions on her innocence or culpability, as well as anxieties about gender and mothering. During the trial, the headlines accompanying the images declared: ‘Azaria: Trial of the decade’, ‘Bloody handprint on jump-suit’, ‘Baby’s blood on scissors’, ‘Azaria’s throat cut: QC’, ‘Dingo invented’, ‘Chamberlain’s account laughable’, ‘Poor bubby’s blood in sleeping bag’ and ‘Lindy the killer’. Lindy Chamberlain describes the combined impact of the headlines and the photographs: ‘I have seen pictures of myself that I have not even recognised, and it has only been the caption underneath that has told me it is supposed to be me. When you want to make things look bad you print no smiling photos and you say emotive words like “guilt” and “anger”.’54

10.9 Michael and Lindy Chamberlain arrive at the Alice Springs Courthouse during the second inquest into the disappearance of their baby daughter, Azaria Chamberlain, at Ayers Rock (Uluru), 13 September 1982. Photographer Nigel McNeil, published in the Sydney Morning Herald (Nigel McNeil/Fairfax Syndication).

Gaining access to bereaved family and friends, like the Chamberlain family, is an important if dark aspect of newspaper photography. One of the most contested rituals is the ‘death knock’ or, using the parlance of the 1970s, ‘intrusion’. This occurs when editors dispatch journalists and photographers to ask the family how they’ve been affected by a death, either criminal or accidental. A photographer is usually enlisted, with the aim of getting a photograph of the deceased, or to photograph a family member, often holding a photo of their loved one.55 Verity Chambers reminds us that a death knock almost always happens in the hours following somebody’s death, so usually the family hasn’t had any time to process what’s happened: ‘Often that’s hitting them when they’re terribly vulnerable; if you ask them for consent, they might make a different decision a week later.’ One photographer candidly explains that press photographers, ‘whether we admit it or not, we’re persuading people to do things they don’t want to do. People are always uncomfortable about the process of being photographed but there is a legitimate reason for needing to persuade people to be photographed.’

Photographers universally dread the death knock. Borrow says approaching people at the lowest moment of their lives is ‘probably one of the harder things to do’. Stevens says that he spent most of his time avoiding the death knock, and both Tindale and Lorrie Graham mention the importance of gentle negotiation. For the latter, death knocks were also educational. ‘They teach you more about what not to do … than what to do. About the way you want to live your life, or the way you conduct yourself with people.’ Mervyn Bishop maintains it was one of the worst things, particularly when children were involved. Ruthless journalists compounded Bishop’s feelings of uneasiness.

Grove elaborates on the unethical behaviour of some of his colleagues: ‘The Daily Mirror and the Sydney Sun were fierce competitors and fought tooth and nail. They’d do some terrible things. They’d turn up to a death knock, where they’d ask a family member of a deceased person for some pictures of their loved one. They ask if they could take the whole album back to the office so that they’d know, when their competitors turned up, there wouldn’t be any photos for them to use.’ Geoff Turner notes that one survivor of the Port Arthur massacre alleged that she and her daughter were harassed by photographers after leaving Port Arthur and were woken at 2 am by journalists.56

Sometimes journalists and photographers tell the news desk that the family was not at home. ‘The editor would want you to try again, but you’d go back and knock on the grass and just say they wouldn’t talk,’ explains Guy Magowan. ‘The grass knock would happen reasonably frequently.’57 Stephens recalls times when, ‘all the attending photographers agreed that they would not knock on the door. Sometimes intruding is just the wrong thing to do.’ Today, this kind of pact with the opposition is less likely to occur, with an increasing number of freelancers and agency photographers refusing to comply with a collective arrangement.

What journalists call ‘the death watch’ can involve intrusion into others’ grief and the invasion of privacy. Access occurs in a number of ways: when contacting the families; during an arrest; at funerals; even, in some cases, in the immediate aftermath of a murder. According to the Australian Press Council, the obtaining of news and photographs should ‘be carried out with sympathy and discretion’. But the recommendations are ambiguous. ‘Reporters and photographers should do nothing to cause pain or humiliation to bereaved or distressed people unless it is clear that the publication of the news or pictures will serve a legitimate public interest,’ the council stipulates, ‘and there is no other reasonably practicable means of obtaining the material’.58

Despite the potential for exploitation and sensationalism, the initial contact could uncover remarkable stories.59 Some people would welcome a photographer into the house because it gave them an opportunity to record that their loved one had existed, Chambers recalls. This intimacy can be compromising, though, especially when grieving family members regard photographers as counsellors. ‘We have to be careful about how we treat people when they’re in shock because people will tell you a lot of things,’ Stephens says. ‘And sometimes that’s very cathartic for them, but it’s not always healthy.’

After the brutal rape and murder of their daughter, Anita Cobby, in 1986, Garry and Grace Lynch developed a close relationship with sections of the press and enlisted them when advocating for victims’ rights and truth in sentencing laws. Phyllis Chan, the mother of thirteen-year-old Karmein, continued to appeal to the media after her daughter was abducted by one of Australia’s most notorious child sex offenders, ‘Mr Cruel’. She allowed photographers intimate access when she and her daughters conducted a service for Karmein in May 1992 at the spot where her body was discovered in Thomastown. The newspapers agreed to her request that the girls’ faces not be shown. Mr Cruel has never been identified. Bruce and Denise Morcombe campaigned to keep their son Daniel’s abduction in the public eye until his murderer was convicted eleven years later in 2014.

Ongoing visual attention and a galvanised press can also keep ‘cold cases’ in the public eye. In 1983, Ray Sizer photographed Michelle Buckingham’s mother, Elvira, holding a photograph of her sixteen-year-old daughter, who had been stabbed nineteen times. Michelle Buckingham lived north of Shepparton, not far from Sizer’s family home. He recalls interviewing Elvira and taking a picture of her sitting on her bed with a teddy bear and in a sense ‘confronting her grief’. Sizer never forgot the murder and encouraged colleagues to stay with the story: ‘I’d actually been trying to get journalists to start chasing up cold cases but nothing ever happened and we’ve interviewed Michelle’s mum again. And every time I see her, I give her a hug. I pushed Tammy [journalist Tammy Mills] but Tammy certainly did the work, did the hard work.’

The case was reopened in 2012. After years of police work and Mills’ report, a witness came forward, prompted by Sizer’s photograph of Elvira Buckingham. Thirty-one years after the murder, Sizer photographed Buckingham’s alleged killer, Steven Bradley, being escorted by the police to a small courthouse in Shepparton.60 Bradley was convicted in October 2015. Elvira Buckingham died five weeks before his trial.

Family members or the police supply photographs of victims—now often lifted from social media sites—and these images are seared in the collective consciousness. Chilling headlines accompany poignant snap shots of happier times: the smiling Beaumont children; Donald Mackay, the anti-drugs campaigner; Anita Cobby after winning a beauty title; a radiant Jill Meagher; and a joyful Luke Batty before he was killed by his father in 2014. But until the victim is named, and a photograph released, the reportage is often clinical, prosaic and sometimes unnecessarily sensational. A day after Cobby’s body was discovered and before her identification, the headline read, ‘NAKED WOMAN’S THROAT CUT’.61

Photographs of victims are not only symbolic; they can act as a catalyst. Some of the most powerful newspaper images have influenced social attitudes and legislative change. The case of a two-year-old boy, Daniel Valerio, led to the introduction of mandatory reporting of suspected child abuse in Victoria in 1993. A shocking police photograph of the bruised toddler after he had been hit by his mother’s partner, Paul Aiton, encapsulated institutional inaction and was reportedly obtained by a photographer taking a photograph of the police brief of evidence.62 Daniel was returned to the family home soon after the photo was taken and Aiton then beat him to death in 1990. The photograph was tendered to the Supreme Court as evidence.

10.10 A police photograph of Daniel Valerio, 1990, used as part of the evidence in the trial and then widely published in newspapers. Photographer unknown (supplied by Fairfax Syndication/permission sought from Victoria Police, who advised that they did not believe they had ownership of the photograph).

The coverage of the Port Arthur massacre and photographs of Walter Mikac, a quietly spoken pharmacist who became the face of the national tragedy in the wake of his family’s deaths, influenced the collective determination to restrict gun ownership and enact subsequent reform. The church service for all the victims of the massacre sent a powerful message about gun violence, but it also required a level of photographic intrusion. ‘That’s when emotions took over for most of us,’ Stevens recalls. ‘Because it’s an image of Walter and his brother coming out of the church, which … you‘ve got to take. You can’t not take it but it’s … one of those pictures you don’t like taking.’

10.11 Walter Mikac, who lost his wife and two children during the Port Arthur massacre, is comforted by family and friends at the Memorial Service for the thirty-five victims of the shooting in Tasmania, 1 May 1996. Photographer Rick Stevens, published in the Sydney Morning Herald (Rick Stevens/Fairfax Syndication).

The pictorial representation of loss has, however, changed since the death of Princess Diana and the rise of collective public grieving, with symbolic and virtual outpourings disseminated by Twitter and Facebook. For example, when teacher Stephanie Scott was murdered on the eve of her wedding, #PutYourDressOut encouraged women to express their sadness and solidarity by leaving their wedding dresses outside their homes, and yellow ribbons were tied to the fence of Leeton High School. Newspaper photographs have shown this shift from private mourning to mass displays of grief.

Photographers observe with some relief that social media have made the death knock and other rituals associated with crime reporting less common, and obtaining photographs easier. Journalists and subeditors regularly source images from social media sites, including Facebook, Instagram, Couchsurfing and even dating and swinger’s websites when they relate to particular cases. Chambers says death knocks don’t happen ‘so much anymore because they just rip off someone’s picture from Facebook, which they consider to be in the public domain’.

But publishing social media images can lead to ethical complications, as Chambers points out. The selective use of Mayang Prasetyo’s Facebook photos in reports of her murder and dismemberment at the hands of her husband Marcus Volke in 2014 is one example. The Courier-Mail and international tabloids, including the New York Post, used a Facebook photograph of Prasetyo in her bikini in syndicated reports of her death. The reports were accompanied by lurid headlines such as ‘MONSTER CHEF AND THE SHE MALE’. Both the use of images and choice of words were rightly criticised.63

Despite these insensitive editorial decisions, newspapers are no longer gatekeepers, which means that social media can further compromise criminal cases. During the emotional Jill Meagher case, the Victoria Police appealed to the public via Facebook to exercise restraint when disseminating the CCTV images of her then accused killer or sharing details about his criminal background, to avoid prejudicing the trial. The CCTV footage of Bayley following Meagher was released by the police and came to define the case. ‘Trial by media’ was displaced by ‘trial by social media’.

With new technology, images are supplied from more diverse but not always credible sources, such as Facebook, screen grabs, Twitter updates, and even Google Street View images. Journalists are increasingly expected to illustrate their stories with their own photographs, which are often poorly composed, homogenised, illustrative flash news pictures of police cars or tape, signifying that ‘we were at the scene’ but little else.

Crime photographs are important historical artefacts shaped by routines and relationships. These factors inform the photographers’ approach, influencing the images they take and, at times, compromising them. Access to crime scenes, victims, families and suspects enhance intimacy and accuracy, but the ethics and fraternisation involved are sometimes questionable and invasive. Reflecting on a lost era, photographers note how their images have illustrated both continuity and change—bank robberies and prison escapees, for instance, are no longer photographic staples. Powerful photographs of crime are both deeply moving and, by their nature, intrusive. They exploit some victims and can provide a voice to people who would otherwise go unheard. They are an essential aspect of news photography, capturing brutality, aching loss, domestic violence, child neglect, injustice and courage.