FAY ANDERSON

AS DOUG UNDERWOOD reminds us, journalists have long trafficked in the causes of trauma.1 From the shipwreck and storm chronicles of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to contemporary newspaper photographs of bushfires, floods, drought, cyclones and accidents, issues of suffering, ethics and loss have been associated with the reporting of disaster.2 Whether natural or human-made, disaster and devastation have always been persistent themes in the press, as has the centrality of the landscape in the national consciousness.3

In any disaster story, the primary objective is to capture the magnitude of the destruction. ‘It’s easy pictorially to go into an area where there’s a picture everywhere you look,’ explains Rick Stevens. ‘But, in a lot of cases, you’ve got to be fairly sensitive too about what you’re showing and how you go about it. It’s there in front of you; you’ve just got to record it.’ Fairfax’s Nick Moir, who has built his reputation covering extreme weather and environmental events, elaborates. The role of a disaster photograph is to show the ‘epic, meteorological nightmare and when the storm or fire is the most powerful and dangerous’, to depict the extent of the destruction and to draw attention to people’s plight.

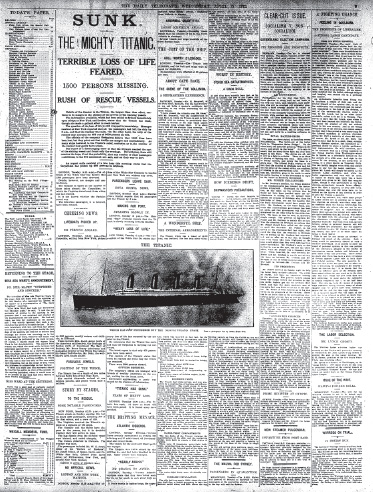

It was not by chance that the first photograph published in an Australian newspaper in 1888 was of a train accident. Disaster has immediate appeal and inspires public curiosity. Yet the iconography of disaster, until the ascendancy of camera phones, has often revealed the inadequacy and challenges of news photography, since photographers usually arrived after the event.4 Almost twenty-five years after the 1888 train accident, one of the most enduring disaster narratives originated when the Titanic sank to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean on 15 April 1912. Its visual treatment reveals how disaster was represented in the early twentieth century, how technology shaped the story, and the commercial strategy of the newspapers. If photographs were used, they were limited to a file image of the Titanic before its departure from the Southampton docks—only artists’ illustrations were able to show the ship’s collision with the iceberg. Later, newspapers published grainy photographs of survivors or thumbnails of high-profile casualties and the primary villain, JB Ismay, the managing director of the White Star Line.

News of the sinking took two days to reach Australia and reports were buried on the inside pages, with confirmation of the loss of more than fifteen hundred lives appearing days later. At this time, the early pages of many newspapers (including the front page) were dedicated to classified advertisements, shipping news and notices rather than hard news. In the case of the Daily Telegraph, news of the doomed ship’s demise was printed on page nine.

11.1 The Titanic, Daily Telegraph, 17 April 1912, page 9. Photographer not cited (News Corporation Australia/National Library of Australia).

The reporting of early bushfires illuminates the trajectory of disaster representation. Due to slow communication and transport, photographers often arrived several hours after the event, if at all. The Victorian bushfires on 15 January 1939, known as the Black Friday fires, influenced how subsequent bushfires were photographed.5 The reports were heavily illustrated with close-up images of the fire; the remains of homes; destroyed buildings and cars; the random nature of devastation, with one solitary house still standing or a lone chimney; and symbolic motifs featuring toys and banal household items. The lexicon associated with these images included the ‘perished’, ‘devastation’, ‘desolation’, ‘agony’ and ‘holocaust’.

The coverage was gendered. Women were ‘refugees’ watching their ‘gallant, menfolk’, according to one report.6 Men were either heroic firefighters or survivors. The firefighters’ images evoked the virtues and physicality of the Anzac: tough, laconic, dependable and fearless.7 Many of these features have continued in bushfire representation. Black Friday continues to resonate because it is part of the older photographers’ collective memory. They recall their mentors’ stories of people climbing into water tanks and getting boiled alive or anecdotes of miraculous escape. Fate—both fortunate and tragic—is a central theme of disaster reporting.

Coverage of the Tasmanian bushfires in 1967—indeed fire coverage generally until the late 1990s—did not dramatically deviate from the established photographic style, except that aerial views were used to show the scale of the disaster, photographers were expected to get even closer, and the prime minister and assorted politicians made mandatory appearances to ‘take a look’.8 There was also the occasional photograph of a male villain, an arsonist or suspect, or a feckless bureaucrat.

Due to the frequency of bushfires in Australia, most if not all staff photographers have covered fires. Moir says that his ‘aim is to show how scary, violent and nasty bushfires are and to get as close as possible’. Disaster can promise beautiful suffering. As Bruce Postle observes, ‘bushfires especially, floods, drought, made dramatic photos’.9 Several picture editors credit Simon O’Dwyer’s work with providing a compelling visual perspective on Australia and bushfires.

11.2 A raging bushfire forces a fire brigade member to hide from flames near Orangeville in south-western Sydney on 26 December 2001. Photographer Nick Moir, published in the Sydney Morning Herald (Nick Moir/Fairfax Syndication).

In their recollections, some photographers discuss bushfires more than other natural disasters because of their ‘crazy’ unpredictability, the fury, and the danger of getting lost in the smoke. Moir notes that ‘with bushfires, it’s all about remaining calm, knowing where you are and thinking really logically. It’s when you can’t see where you’re going, when you get caught in thick smoke, that it does get scary.’ Terry Phelan repeats one mentor’s advice, ‘Don’t get caught in the open,’ and Alan Porritt offers another mantra: ‘Just remember, you can’t outrun the wind.’ Several photographers have been close to losing their lives. Colin Bull and a journalist from the Sun News-Pictorial found themselves stranded along the track in Cockatoo during the 1983 Ash Wednesday fires, in which forty-seven people died across Victoria, and twenty-eight in South Australia. Earlier in the day they had been with a fire crew who perished. Bull’s camera was so hot that they were throwing it between themselves ‘because they couldn’t hang onto the camera’.10

Craig Borrow was traumatised when, as a callow nineteen-year-old in Aireys Inlet during the Ash Wednesday fires, he found himself alone and without any communication in inaccessible, densely forested terrain and with only one road out. ‘It was just dark, it was just black,’ he says ‘It was quite frightening. The wind was just phenomenal. And there was just sparks in the air, it was just like fireworks. I’d just started to take photos but I’d never done a fire before and I didn’t know exposures, and this was film in those days, and I was thinking, “My God, this is Armageddon.” As I’m running back to the car, there was a tree to my left and it just burst into flames. It was just that hot that things were bursting into flames. Telegraph poles were on fire. It happened so quickly.’

Before the advent of the emergency service’s occupational health and safety legislation, photographers had unmonitored access to fires. They wore shorts and singlets or, incongruously, before the 1970s, shirts and ties if they were sent from another assignment in the city. They hitched or jumped on the back of fire trucks and then later worked out how to get back to their cars.11 Their pictures reflect these interactions and this intimacy. Porritt recalls driving down a country road when a man appeared: ‘He got closer to the car, and the skin was just hanging off him.’

During this earlier era, when photographers accompanied the firefighters, the lines were sometimes blurred. It was not unheard of for them to help the ‘firies’. ‘You were there with them and you’re getting the results. It was challenging: it was exciting,’ Guy Magowan says. Borrow’s experience reflected the cavalier institutional attitude to health and safety during the 1980s. When he returned home early in the morning, covered in ash and reeking of smoke, his family were quite complacent. ‘And I’m thinking, “Gee, the world’s nearly ended.” After what I’d seen, I thought that Lorne and Aireys Inlet had basically just been wiped off the face of the earth.’

Since the late 1990s, photographers have been given basic bushfire safety training with emergency services agencies, issued with an accreditation card and been required to wear fire protection gear. They check in at a staging ground, which is sometimes miles away from the fire, and are escorted in. Forensic teams also provide pooling opportunities, taking the media to view bodies and devastation.

Moir, who voluntarily undertook firefighting training with the Rural Fire Service, is more ambivalent about the media training he later received, observing that ‘it gives you enough information to get into trouble and not enough to get out’. The new lines of control have frustrated some photographers, as Porritt, who covered the 2003 Canberra fires, and Magowan from the West Australian acknowledge. Jason South says that photographers are hampered by the rules, and those who want ‘decent fire pictures usually drive themselves in through the back’: ‘It’s more dangerous now; you’ve got to get in before the roadblocks. They cause me anxiety, not fear, the bushfires now, because you’ve got to avoid the police; that just adds another whole layer of difficulty.’ The logistics of gaining access to a scene are as important as a safe exit, South observes.

Fire and disaster photography more generally are affected by changing logistical problems. Older photographers traversed hundreds of kilometres to reach fires, floods, plane and train accidents, and road trauma. The remoteness compounded the technological difficulties. Before digital, they sometimes ran out of film or, due to heat and climate conditions, found the chemicals compromised. More specifically, they were driven by time pressures: ‘You’ve got to get there; you’ve got to get the picture; you’ve got to make the deadline.’ With digital, the deadline has gone, and as Porritt says, ‘speed is king’. Photographers have to ‘get the picture out first’.

Newspapers no longer rely solely on their photographers. With the demand for more photographs, editors are sourcing images directly from the emergency services. During the Black Saturday fires in 2009, the Country Fire Authority was shooting photographs from its trucks. Many of the images were published over the first week and featured on a number of front pages. One of these was the touching photograph of David Tree sharing his water with a koala, later named Sam, in the Strzelecki State Forest. The image, taken by Mark Pardew, a firefighter for the Department of Sustainability and Environment, would prove a ‘double-edged sword’ for Tree, who was both celebrated and abused on social media, with accusations that he staged the photograph or abandoned the koala.12 While Pardew’s photograph wasn’t posed, a number of photographers mention the proliferation of digitally manipulated photographs. As long as they’ve got flame and a couple of ‘firies’, no one knows the difference, Porritt observes about the approach of less ethical photographers.

Like fire images, cyclone photography emphasises extensive damage, efforts to mitigate the destruction, and the individuals affected by the disaster.13 Disaster visuals present various perspectives on the relationships between humans and nature.14 Press photographs often convey nature’s power, both visually and symbolically, and masculine dominance in disaster management. These depictions, however, depend on access and communication.

In early cyclone coverage, news photographers were rarely able ‘to get the picture’. For example, there were few photographs taken of the cyclone that hit Broome on 26 March 1935, destroying a pearling fleet at the Lacepede Islands and killing 141 people. The published images show minor damage to houses and ships, and were sourced from the Aborigines Department.15 Despite this source, the experience of the Indigenous community was largely missing in the coverage.

This pictorial invisibility extended to the Larrakia people during Cyclone Tracy forty years later. Cyclone Tracy is arguably the most significant tropical cyclone in Australia’s history. It ripped through Darwin on Christmas Eve in 1974, causing sixty-five deaths and the destruction of most of Darwin, with 90 per cent of homes rendered uninhabitable, and affecting the Australian perspective on the tropical cyclone threat.16 Unlike Broome, Cyclone Tracy attracted significant media interest, despite failed communication and fragmented early reports. It was, according to Bruce Howard, perhaps the ‘biggest news event ever in the country’. This was despite the fact that the Whitlam government had considered banning all media, and initially only emergency services were given entry, so the press contingent was small.

Photographers’ recollections focus as much on the challenges of cadging flights and the anxieties over equipment as on their experiences on the ground. Keith Barlow negotiated an early flight on Christmas Day with several of his ACP colleagues from the Daily Telegraph. Barlow arrived in Darwin at midnight with no change of clothes, an apple, one camera and three or four rolls of film. Stevens went to work in Sydney on Christmas Day, managing through journalist Bob Howgarth’s Canberra contacts to get on a Hercules carrying emergency supplies from the Richmond airbase, returning home six weeks later. He flew into Darwin at first light on Boxing Day with two cameras, ‘a whole heap of film’ and a transmitter but no power.

Howard’s journey was even more circuitous, and on his arrival in Alice Springs on Boxing Day, he managed to leave a media scrum behind. Fortuitously, several weeks before, Howard had photographed Jim Cairns, the then acting prime minister, and after seeing him at the airport, he wrote him a note emphasising the importance of photographing what had happened. During the flight, Howard conducted the rudimentary photographers’ check: camera, lenses, film. The one thing missing were envelopes. Howard removed the ‘chuck bags’ out of the backs of the plane seats and put them in his camera bag.

By late Boxing Day, a telephone line and telex had been set up, but there was no power for days, so the picturegram machine did not work and there was no way for photographers to transmit their images. If it was difficult to get in, it was even more challenging to send the film back to the newsroom. Barlow photographed the airport where people had sought refuge and sent the first colour photographs for the Women’s Weekly back to the ACP newsroom on a returning flight. Howard considered the route: the first commercial flight would be the milk run from Darwin down the coast to Perth, and then the red-eye special coming through the night would be in Melbourne in time to make the first-edition the next day. After hitchhiking on two trucks to the airport, Howard put all his films and the caption material into one of the vomit bags, addressed it to the picture editor of the Herald with the message ‘Ring on arrival’ and sent it out on a Fokker Friendship aircraft.

As the days progressed, Lloyd Brown and Howard shot their pictures and sent their film from the RAAF base at the airport. Stevens and Howgarth hired a car and roamed around. ‘It was a huge job,’ Stevens recalls. ‘It was a lot bigger than what anybody had thought because back in Sydney they still didn’t know what’d actually happened.’ Stevens gave his first envelope stuffed with film to an injured man on a stretcher who was being evacuated to a Sydney hospital. Before electricity was connected again, all the photographs from Darwin were taken in a vacuum. The photographers did not see their photographs developed or published until they returned home, and the newspapers insisted that the ‘graphic’ photos arrive by direct jet.17

Cyclones are an important media event because of their catastrophic visual appeal, but there were no photographs from Darwin ‘as it happened’. The photographers’ often innovative approaches to photographing the devastation dominate their recollections. The flatness of Darwin did not permit an easy vantage, Stevens remembers. ‘It’s no good just photographing one house that’s lost a roof. You need to show a row of houses.’ Stevens climbed to the top of a tower to get an angle showing the extent of the destruction. ‘I had this massive view. All the bits of tin, the roofs, were all wrapped around the trees. There wasn’t one leaf left on the trees, and every house underneath was just flattened. That was probably my major picture. I’d never seen anything like that before.’

Brown, who hitchhiked into Darwin, describes the scenes as unbelievable. ‘I’d never ever since or before covered anything like it.’ Barry Baker concedes that the photos ‘were quite easy to take but I had to get around and get them’. Navigating the city was problematic. They found the federal police difficult to deal with, and the local police were even worse, denying them access and questioning what they were doing. ‘They were quite nasty to us at times,’ Baker says.18

While bodies were completely absent in the coverage, the photographers say they disbelieved the official death toll, arguing that it was underestimated, given that the itinerant people were not properly registered and the Indigenous population was largely ignored. One of the few images of an Indigenous child (unnamed) was taken at Darwin Hospital with two figures of institutional authority, Jim Cairns and a nurse, in the frame. Children provided pathos.19

The dominant coverage showed the devastation, the wounded, emergency workers at work and people collecting water. There were related stories about growing lawlessness, bruised optimism, and exodus. Within several weeks, three-quarters of Darwin’s population had left. The photographers recall the desperation and the fear of disease—some men even disguising themselves as women to get on evacuation planes—as well as widespread looting and threats to shoot. In the visual representation of disaster, men are the dominant actors in times of crisis, appearing either as heroes and outback warriors or, occasionally, as cowards.20

The coverage of Darwin also provided an alternative narrative about women. Five days after the cyclone, Vic Sumner from the SMH photographed Helen Greentree clutching her dog Tiffany outside her tent, with her 12-gauge shotgun—to frighten off looters—in her lap. Resilience was a dominant theme.

11.3 Shaken by the power of Cyclone Tracy, Helen Greentree sits outside her tent, her dog Tiffany clutched to her chest and her 12-gauge shotgun resting on her lap, 29 December 1974. Photographer Vic Sumner, published in the Sydney Morning Herald (Vic Sumner/Fairfax Syndication).

Symbolic images, reminiscent of bushfire coverage, were equally important for Darwin: the washing being hung out ‘amid ruins’, ‘Jim Casey returning from holidays, suitcase in hand’ to his ruined house, and Danny McIver holding his cat, a sink and a shotgun amid the rubble.21 Absent were the brief biographies of all the Australian casualties, accompanied by small photographs, a mandatory feature of more recent disaster reportage.

When asked how magazines differ from newspapers, Neville Waller explains that ‘they weren’t into fire and floods to the same degree’. Like bushfires, floods are a staple in daily papers and offer a similar narrative of drama, excitement, tragedy and recovery. From the Townsville floods of 1927 to Northern Tasmania in 1929, and from the Hunter Valley in 1955 to Neville Bowler’s superb 1972 image of water gushing down Elizabeth Street in Melbourne, the flood photograph has captured the raging torrent of water and a different form of helplessness.22 Between 1852 and 2011, floods have killed at least 951 people and the damage has cost an estimated $4.76 billion.23

The photographers’ resourcefulness was as compelling as the event itself, particularly in the early period of heavy cameras, cumbersome equipment and picturegram machines. Barry Norman recalls going to the Maitland floods in February 1955 as a sixteen-year-old cadet for the Telegraph. He was assisting the renowned John Jones, who lost contact with Norman while covering a navy helicopter that crashed while trying to rescue stranded people. So Norman was instructed to find a pharmacy, buy a Box Brownie and film, and photograph the flood damage himself. The camera and the photos, Norman says, weren’t very good.

In 2011, beginning with rains in September and then culminating with Category 1 Cyclone Tasha crossing the Far North Queensland coast on 24 December, floods decimated parts of Queensland, with thirty-five reported deaths.24 On his day off, Neville Madsen, a Toowoomba Chronicle photographer, took a series of photographs that became the Walkley Award–winning photo essay ‘Toowoomba flood rescue’. It includes a striking image of an emergency worker struggling to save a mother and daughter from floodwaters surging through Toowoomba streets. Madsen says that ‘getting the perfect snap is a mix of logistics, emotion and simply watching and waiting. News photography was often about ensuring you were in the right place at the right time.’25

11.4 Hannah Reardon-Smith and her mother Kathryn struggling against floodwaters as an emergency services worker battles to rescue them from flash flooding in Dent Street, Toowoomba. Photographer Neville Madsen, published in the Toowoomba Chronicle, 2011 (Neville Madsen/APN Australian Regional Media).

In contrast to Madsen’s frightening images, photographs of floods can also convey humour, particularly those featuring animals and accompanied by droll captions. Flood photographs tend to convey a distinctive brand of Australian masculinity and attire, from the ties and hats before 1950 to the tight stubbies and singlets of the 1970s and mullet haircuts of the 1980s.

It is impossible to examine disaster photography without acknowledging the newspaper industry’s widespread and accepted practice of staging or posing photographs. It was a highly valued skill. These photographs functioned to illustrate a point or to make an event look interesting. Meaningful images are often descriptive and symbolically significant; the photograph of a teddy bear amid rubble has become a rhetorical device, and audiences rarely consider the provenance. When questioned about set-ups, those photographers reputed to be the most notorious ‘stagers’ seem to be the most self-conscious, and the most reluctant to discuss them.

Most of the older photographers have set up photographs. When they started, it was an expected part of the job, and a few are refreshingly candid. After the first group of photographers had left Darwin, Phelan was sent there to record the scenes of reconstruction. ‘And that’s one of the times, even on big news jobs, when you’ve still got to move things around the way you want them,’ Phelan explains. After finding the worst street, Phelan asked a young mother and her young child, who was on a tricycle nearby, to come back to the street. Standing on his car, he took a photograph of the child. ‘I know some people might think it’s cheating, but it’s just moving things around. It was all there. I just put it into the spot where I wanted it to be.’ The editor ran it ‘big’ with the caption, ‘A spark of life’.

Howard explains the genesis of a photo of a little girl with half a basketball after the Mount Macedon fire: ‘The picture was set up in that I had to tell her to stand near the burnt tree and hold the ball and not look at the camera … In the background, using a wide-angle lens, were the smoking remains of what had been their family home. So it had been pretty traumatic. And I said, “Now, look away,” so that’s why she’s looking away … People will look at it and say that it’s an instant news picture after a terrible bushfire. Well, it is in a way. But not quite.’

And Waller recalls the Jindabyne floods when they rowed two elderly ladies out into the floodwaters. It wasn’t considered faking because they actually went out there, Waller says. One of the most discussed photographs was taken by Barlow. The treatment of his image of a rooster with an egg amid the flotsam of heavy floods in Riverstone in December 1961 still rankles him. The editor of the Women’s Weekly, Esme Fenston, rang Barlow and asked if the picture was manipulated and if the egg had been placed in the shot. Barlow denied it, but the Weekly refused to publish the image. The following April, though, Life magazine devoted a full page to the photograph, and it later featured in an advertising campaign in the United States.26 A number of photographers insist the photograph wasn’t staged and that a newspaper would have published it.

One of the most challenging photographs to take, and one that lends itself to visual cliché and manipulation, is the drought photograph. There are the ‘go-to pictures’ of cracked earth and animal carcasses, but these are often not even taken in Australia. Newspapers increasingly source these cheap, generic file pictures from Getty and other agencies, and their use is devoid of relevance, attribution or context.27

Despite these frustrations, the photographers we interviewed were committed to recording drought and climate change. Don McCullin, the renowned British photographer, emphasises the importance of a photographer’s ‘emotional approach’ and awareness.28 The more poignant images reflect an emotional connection with the farmers. Renee Nowytarger explains the context surrounding one of her photographs of a farmer in a pink dust storm, his head bowed as he walks towards the cattle he has to shoot because there isn’t enough food or water: ‘You don’t need to see the gun to the head of the cow. It’s the farmer’s demeanour. He looked broken. It was more personal for me because I’d spoken to him about it and how much he hated doing it, and it was just raw for him, and it meant something to me that it wasn’t in your face but you could tell what was happening. You knew that that’s what had to happen.’ Lorrie Graham, who published a book of her photographs on the rural crisis, says the drought became personal for her after she became close to the farmers who were being ‘turfed off their land’.

11.5 Gavin Gaiter on his property Packsaddle walking in a sand storm (caused by the drought). He has resorted to shooting poor, unhealthy cattle that don’t have the strength to survive. Photographer Renee Nowytarger, published in the Australian (Renee Nowytarger/Newspix).

If drought is visually difficult to convey, there are some disasters that demand attention. Editorial gatekeeping is influenced by a hierarchy of factors: human-interest, national prominence, graphic appeal, emotional engagement, exclusivity and proximity, both cultural and geographical.29 Many claims are made about the commercialisation of disaster.30 Now it’s considered ‘clickbait’. Whether natural, or due to human error, some disasters are important media events. Three in particular deserve further examination: the Westgate Bridge collapse and the Granville train disaster—both of which helped to define the 1970s and the psyches of the cities they affected—and, later, Thredbo.

On 15 October 1970, the partially constructed Westgate Bridge in Melbourne collapsed, killing thirty-five people. An amateur photographer, a ten-year boy who was standing across the river, took one of the important images. The boy’s father brought him to the offices of the Sun News-Pictorial with the unprocessed film, and the image ran as the main picture the following day.31 As Brown observes, ‘it wasn’t a great picture’. The grainy image is devoid of any compositional skill, but the photograph’s worth derives from three non-aesthetic factors: it shows the dust rising at the moment the bridge collapses, conveying a clichéd sense of ‘history in the making’; it is an important precursor to the now endemic circulation of photographs of disaster as it happens; and it reveals the early exchange of in-demand images from the public.

11.6 Front page of the Sun News-Pictorial, 16 October 1970, relating to the collapse of the Westgate Bridge. Photographer Udo Rockman (News Corporation Australia/Newspix).

Most of the photographers assigned on the day missed Victoria’s most important industrial accident. Brown, whose car was installed with an early car radio, left a nearby job and recalls ‘how some men rode that great slab of steel and concrete from thirty metres up in the sky down to the ground, and weren’t killed. It was amazing.’

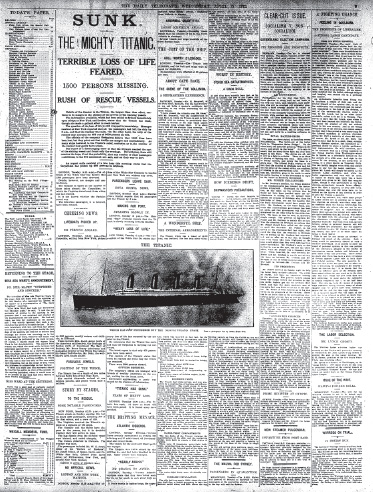

There were some compelling pictures. One of the most visually arresting and intimate was taken by an uncredited photographer. It shows a workman covered in oil and blood, his head bandaged and hands resting on his lap. Historian Rose Butler notes an almost complete absence of weeping men in the Australian cultural discourse.32 The absence is particularly evident in disaster imagery. All the victims of the bridge collapse were construction workers—supervisors, steel workers, riggers and welders working on the bridge when 2000 tons of steel and concrete broke away and dropped 50 metres. Most were immigrants.33

11.7 Westgate Bridge worker, published in the Age, 16 October 1970, page 3. Photographer not cited (Fairfax Syndication).

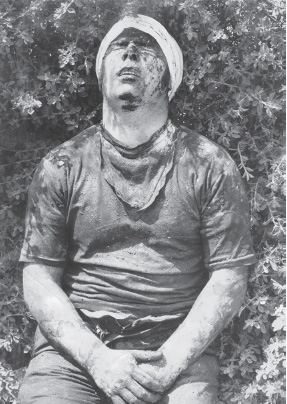

Seven years later, on a warm summer morning on 18 January 1977, a crowded Sydney-bound train derailed near the western-suburbs station of Granville, pushing away piers that help up a road bridge, which then collapsed on the train. Eighty-three people died and more than two hundred were injured in the worst rail accident in Australian history.

The collision occurred at 8.07 am, which suited the news production schedules of the afternoon dailies, so the initial coverage blanketed successive afternoon editions of the Sydney Mirror and the Sydney Sun. Russell McPhedran was one of the first on the scene. He spent the entire day taking photographs of the dead and injured and sending film back to the office. It was, he says, ‘one of the worst stories’ he had to photograph. Steve Grove remembers it as the ‘biggest disaster story’. As he stood in the darkroom developing the pictures, he realised it was a very significant event in the city’s history, but there were some pictures that weren’t published. ‘They were too horrific for you to see. It came down to a sense of responsibility … You’d think about the fact that we’re a morning newspaper, and people always say you don’t want to be sitting there and eating your Weeties and looking at a bunch of dead bodies.’ Others, including Porritt, missed the ‘biggest story’ because they were already out on jobs and, in the days before mobile technology, were only contactable by beepers.

Although the two accidents were entirely different, and many of the victims at Granville were women and children rather than construction workers, the visual representations did not dramatically differ. Photographs of Granville include aerial photographs, distant but concealed images of casualties, and portraits of survivors, rescuers (described as ‘an army of heroes’ and ‘unknown soldiers’) and priests.

11.8 Granville Train Disaster, Daily Mirror, 18 January 1977, page 1. Photographer not cited (National Library of Australia).

The tabloid newspapers used wrap-arounds for both disasters, with an emphasis on the ‘pictures’ for the first three days before the attention diminished. Missing in the coverage was the contemporary convention of biographical profiles of the victims and the coverage of every funeral. The Westgate Bridge collapse resulted in a royal commission, and a judicial inquiry investigated the Granville disaster.

The coverage of disasters had changed by 1997, when late on the night of Wednesday, 30 July, a landslide destroyed the village and ski resort at Thredbo in New South Wales, killing eighteen people. Photographers were now kept away at a discrete distance. The last survivor, ski instructor Stuart Diver, endured more than three days entombed underground next to his dying wife, Sally, before his rescue on 2 August. Graham Tidy recalls arriving at sunset. The police had established roadblocks and escorted the media to the other side of the valley, where they trained their cameras and lenses on the area where the rescuers were digging. The photographers, unlike the journalists, waited outside on long shifts. Mike Bowers photographed every one of the bodies that were removed. After three days, Tidy was driving home when, halfway down the mountain, he heard a newsflash saying they’d heard voices. He slammed on the brakes and turned around: ‘It wasn’t for another eight hours when they pulled Stuart Diver out. It was very dark and cold. I got the images of him being pulled out from quite a distance. It was nothing like the image you saw in the paper that was taken just above him by one of the workers. I jumped in the car and drove back to Canberra with the unprocessed film. It was a pretty memorable time.’ But despite the waiting, and as Tidy alludes, it was a photograph taken by Sydney paramedic James Porter as Diver was pulled from the rubble that became the most circulated photograph of the landslide.34

‘Dramatic scenes’ of wrecked and twisted cars are a more frequent feature of Australian newspapers than are landslides. One photographer recalls riding the tow trucks on the Hume Highway ‘covering smashes’ and getting ‘really good on the spot pictures’. The photographs of road trauma often conveyed spectacle and could exploit the victims, but the stories could also advocate powerfully for change in an era without enforced speed limits, compulsory seat belts, blood alcohol limits or penalties. In 1959, the Courier-Mail called for greater care in the wake of high road fatalities during the Christmas period. A decade later, the editor of the Sun News-Pictorial, Harry Gordon, led the campaign ‘Declare War on 1034’, which demanded action on Victoria’s high death toll after 1034 road deaths in 1969.35

A number of photographers, including Grant Wells, convincingly argue that photographing car accidents is of public interest and a deterrent. ‘That’s what we do when showing these things. Obviously, it’s very personal and hurtful for any family involved, but you could argue that there’s a wider good,’ Wells says. Ray Sizer, a regional photographer from Shepparton, agrees. When a fatal accident picture appears on the front page, ‘That’s my justification,’ he observes. ‘If there’s one life we can save by someone seeing that picture and thinking, “Oh well, maybe I better slow down,” or some parent having a talk to their son and saying, “This could be you next time,” that sort of thing. So that’s our role, to promote road safety and make people think and be aware of it.’ While the perception of photographic power is often anecdotal, the declining fatality statistics that follow TAC campaigns, greater police presence and changed laws appear to validate Sizer’s point.

But photographers also self-censor. Darren Tindale recalls a head-on accident in which a very young child had been killed. He put his camera down when an ambulance officer ‘picked this little body up off the road’. Some refer to a ‘file’ of pictures that will never be published. ‘That goes in the file,’ a number of photographers told us of the images that were too graphic.

In the midst of all disaster stories are the traumatised communities. Cait McMahon alerts us to the paradox of identifying with victims and wanting to protect them from further harm, while simultaneously indulging in curiosity and voyeurism.36 Some photographers reveal still raw emotions when discussing public criticism of their work. Occasionally they receive hate mail, and those who photograph for local papers often experience particular hostility because they are part of a small community and conspicuous. Wells remembers being abused quite frequently when covering car accidents and, more specifically, in 2013 when two miners were killed at the Mount Lyell copper mine. The regional photographers have to be more sensitive because they usually know the victims and have to live with the people they cover. They can’t just have a ‘kick your door’ attitude, Wells observes. Even their relationships with the emergency services can be compromised. There is important trust that a photographer can gain by being in a local community for a period of time. ‘If you mess up in a situation like that, you’re tarred with that brush forever by everyone who comes through the force,’ he says.

At other times, families of victims have sought photographers out. Justin McManus reflects on whether those affected by the devastating Black Saturday bushfires, which claimed 173 lives, were hostile towards his presence. ‘It depended on the people. Some people didn’t want the media around; others did; others wanted their story told,’ McManus says. ‘My experiences with the people were almost entirely good and positive. A few people in Narbethong on the Sunday after the fire weren’t that happy, but it was so raw at that point and that’s their right; it’s their property I’m intruding on.’

Verity Chambers is equally ‘divided’ about photographers descending on disaster areas and the nature of ‘disaster porn’, as some of the worst excesses are called. Photographic attention can create awareness and aid funding where it is desperately needed (the nationwide telethon appeal to aid Cyclone Tracy’s victims was the precursor), and the public can also begin to understand the enormity of the disaster. At the same time, Chambers is torn about photographers flocking to disaster because of the kudos, and the ‘amazing images no matter where you point your camera’. ‘I know some photographers who seem to lack empathy,’ she says.

Chambers’ ambivalence is partly inspired by her personal experience. In 1991, she photographed an eleven-year-old girl whose mother and brother had been burnt to death in their house during a bushfire. A chaplain of the fire brigade had brought the girl back to the family home, and as she came out onto the road completely overcome with grief, Chambers took her photograph. Images of children and young people appear frequently in the news coverage of disaster events, and their use to tell stories of dramatic events is not unique to the construction of Australian narratives.37 Chambers, who was working for the Daily Telegraph, says, ‘I had to take the photograph; it was my duty as a press photographer.’ When she returned to the newsroom, one of her mentors, Anthony Weate, a senior photographer, told her not to lose the negative. Chambers recalls how the photograph was received: ‘I soon found out that the newsroom had received hundreds of calls wanting to know how they could do that to that poor child. I started thinking, How could we? … I hoped that the photograph would teach other people to not throw a lit butt out a window or make sure that their homes were prepared for fire season. I started to veer toward the didactic thinking that the photograph could have an educational effect. The other side of me knows that this is a kind of intrusion on people’s grief and is voyeuristic.’ The image ran on the front page under the headline ‘Fire Storm’ and won a Walkley Award the following year.

11.9 Rebecca Burns walking through the burnt-out garden after fires at Kenthurst, October 1991. Photographer Verity Chambers (Verity Chambers/Newspix).

The compassionate photographers, like Chambers, admit they wrestle with their conscience about the ethics of photographing traumatised people. Clive Mackinnon still struggles with his decision to photograph a mother and her two teenage children looking at the ruins of their house after the Ash Wednesday bushfire. ‘I pulled up in the car and said, “I’m from the Sun. Do you mind if I take a picture?” And she said, “Do what you like.”’ Mackinnon reflects: ‘It’s a pathetic picture; I was annoyed with myself for taking it, but it was a bloody good picture.’

Magowan continues to grapple with his decision in 2008 to photograph a man who had learned his wife had drowned. Magowan admits that he felt awful because it appeared on the front page. Like many contentious images, it won an award. He expounds on the aftermath: ‘There was that much criticism towards the editor at the time, not towards me. It ended up on Media Watch. It did affect me a bit, that one. But at the end of the day, I’m just doing the job to show this is what can happen in life. I still question, Did I need to take that picture? Because there were other pictures I could’ve taken. But on the other hand, you also question yourself: Why didn’t I try this angle or that angle for any kind of picture?’38

Clearly many photographers recognise the ethical dilemmas of their vocation and acknowledge their feelings of guilt. The issue is complicated by newspapers’ criteria for selecting and discarding photographs. The editorial process is largely based on purely subjective factors, including personal values and cultural sensitivity.39 The abiding agreement in the industry is that you don’t publish recognisable faces, and that dead bodies are usually partially or completely covered. Bowers argues that bearing witness is integral to his vocation and recalls the advice of Robert Whitehead, editor of the SMH: ‘“Dead bodies don’t sell newspapers … Graphic does.” There’s a fine line between the two, and it’s hard. I think finding that line is hard sometimes too.’

The complexity is also compounded by the MEAA Code of Ethics, which is vague in relation to what newspapers can or cannot show. As previously indicated, there is no direct reference to still imagery, bodies or news of a graphic nature. Principle 3 of the Australian Press Council’s Statement of Principles states that respect must be shown for the privacy and sensibilities of individuals, and Principle 5 relates to matters of taste.

A photograph of a dead child can garner acclaim but also convey beauty and heartbreak. Steve Cooper’s Walkley Award–winning photograph for the Australian shows a police officer gently carrying the body of a little girl. Three-year-old Cindy-Lee and her eleven-month-old sister, Raeleen, had been pulled from the arms of their father by surging waters when torrential rains flooded Sydney’s western suburbs on 5 August 1986.40 Cooper’s photograph emphasises the visual poignancy of children, and their association with both risk and nostalgia.41

11.10 A policeman carries the body of toddler Cindy Carrick, who was swept away at Mt Druitt. Photographer Steve Cooper, published in the Australian, 7 August 1986, page 1 (Stephen Cooper/Newspix, supplied by State Library of NSW).

Over ten years later, the Press Council considered complaints against the Adelaide Sunday Mail over its publication on 12 July 1997 of a photograph of a dead child, one of seven members of two related families who were washed from the rocks by a freak wave and drowned at Kiama on the New South Wales coast. And in another case, the Press Council upheld a complaint from a family in 1992 when they objected to a photograph that showed their relative’s body in the passenger seat of a car under a bloodstained white sheet, with a leg protruding from under the covering. The editor, in his defence, argued that road trauma was a ‘huge issue’ and that the public seemed reluctant to take an honest look at a frank depiction of what an accident scene was like.42

In cases where the Press Council has upheld the public’s complaints, rightly or wrongly, it distinguishes between photographs of unidentified victims of foreign carnage and a front-page picture of a body in a local community, where many people might know the deceased.43 The council argues that public distress—and more specifically the suffering of the family and friends of people involved in accidents, tragedies and other occasions of private grief—should not be exacerbated by the publication of such images. ‘There should,’ the Council says, ‘be a compelling and over-riding public interest in their publication.’44

Some might argue that this is a double standard, and decisions not to publish photographs of local bodies has less to do with recognition and privacy than with the press privileging the lives of Australians over other nationalities. In other cases, when the Press Council has refuted the complaints on the basis of taste and privacy and has supported the newspapers, the council has emphasised ‘public interest’, a nebulous concept.

The ethics of showing suffering is more complicated than the Press Council suggests. Moir argues that ‘there is a responsibility to show it but endeavour to do no harm’. McManus took a photograph that illustrates the devastation of the Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria. As he was returning to Narbethong along the Maroondah Highway, McManus saw a body under a sheet and a policeman stationed there, with police tape around it. ‘I said, “Is it okay if I take a picture?” and he said, “Yeah, that’s all right.” It was quiet and it was eerie; there was blue smoke filtering through the bush … It was peaceful … Until you take your mind back a few hours and you think of the firestorm this person must have confronted. You’re processing all of this in a matter of moments while also thinking about how best to photograph this. In fact it was simple: don’t get too close. The power of the picture is in the space and silence; a lone body in the burnt-out landscape. That’s what gives it the power; if I’d had gone closer … it would have lost its context.’

11.11 After the fire at Narbethong, a dead body lies on the side of the Maroondah Highway, 8 February 2009. Photographer Justin McManus, published in the Age (Justin McManus/Fairfax Syndication).

Moir is insistent that it is the public’s responsibility to view these photographs. ‘This stuff needs to be recorded; this is Australia’s greatest natural disaster. People need to know how bad it is.’ Moir says of McManus’ image: ‘People had a problem with that. But our job in the media is to cover stuff, not to pretend it hasn’t happened.’ There is considerable evidence to support the didactic importance of showing suffering and disaster.

In photographers’ recollections of disaster, it is evident that their own professional communities have also been traumatised. Since the 1980s, and largely in response to the increased vulnerability of journalists, several organisations have emerged to provide assistance to the press. The Committee to Protect Journalists was created in 1981 to promote press freedom and the rights of journalists. The Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma (DART) was developed in 1994 and is a ground-breaking resource for journalists who cover disaster and violence. It is dedicated to informed, innovative and ethical news reporting on violence and tragedy.45

DART has expanded the focus of many news organisations, and there is a growing consideration of domestic stories on mental health. There have been numerous major psychiatric and psychological studies conducted on the subject of trauma, which have focused primarily on print journalists, and on photojournalists to a lesser extent.46 The findings are that journalists and photographers can suffer sleeplessness, flashbacks and, in more extreme cases, post-traumatic stress disorder, and their employers rarely alert them to the potential emotional consequences of the job.

Interviews reveal the photographers’ guilt and depression, exacerbated by long hours, physical and mental exhaustion, and alcohol, which is, according to one photographer, ‘a terrific mix’. Trauma can manifest physically. One of the first photographers on the scene at Granville admits that he ‘still gets a bad feeling when driving under a bridge’. But the most profound consequences are the emotional responses. Brown remembers those weeks in Darwin after Cyclone Tracy when he ‘just got up and went back outside and covered the job again’. He says, ‘It was with me all the time. But your job is to record photographic information, not for yourself, but it’s for the rest of Australia and the world. So you get into it.’ The smell of death or of burnt flesh is a potent recollection of a number of photographers.

Photographer Noel Stubbs, who took a Walkley Award–winning photograph of a Vietnam War protester, moved from Sydney to Darwin in 1971 to become chief photographer at the Northern Territory News. Soon after photographing Cyclone Tracy in 1974, he gave up photography to work as a technician with Telstra. His son-in-law, Garry Casey told journalist Nigel Adlam, ‘He rarely touched a camera again. But he was enormously proud of his Walkley Award and spoke about it until his final days.’47 Stubbs’ career choices are a reminder that press photography is not always a lifetime vocation and that even award-winning photographers can depart the profession in a manner that hints at the psychological pressures of the job.

One source of anxiety is the public abuse. One photographer describes the locals at Thredbo who didn’t quite know how to deal with their grief and so made the media the enemy: ‘We were spat on for carrying cameras through the village and called scum, and it was really very nasty … And you’re being abused by everyone from the police to punters, and seventeen-year-old lift attendants. It was just the worst job I think I [have] ever done. I haven’t been back to Thredbo. I’ve had to pass through there a few times and felt sick, basically. It was worse than the tsunami; it was worse than anything I’d ever done.’

A feeling of powerlessness is often expressed. Photographers are observers, while the emergency services are engaged in saving lives. ‘You’re intruding on someone’s grief … And they’re probably at their lowest point in their life and you’re certainly not there to make it better,’ Borrow explains. ‘But the ambos and the police, they are trying to help them.’

The Black Saturday bushfires required photographers to remain on the scene for extended periods, which sometimes exacerbated the trauma both for the photographers and for some in the community. Other locals wanted to tell their stories and welcomed the presence of the media. At the same time, the press were responding to an insatiable interest in the catastrophic event as the public tried to make sense of a complex cauldron of risk.48 Borrow regularly returned to the hamlets over a three-month period. ‘I had to live it. I thought we were just wallowing in, you know, the sadness of it. But that’s what we were doing. I could’ve stayed up there but I just didn’t want to.’ McManus agrees. ‘Your empathy does wear thin; it’s difficult after a few weeks. Hearing similar stories over and over. You reach saturation point. It’s overwhelming hearing of the profound loss and sadness that people are enduring. There comes a point where you just want to take the picture and get out,’ McManus admits. ‘You can’t feign empathy. You take a certain amount of respect into any job you do … you’ve got to keep that professional air about you and respect your subject.’