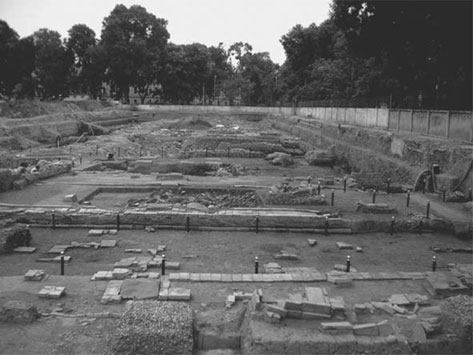

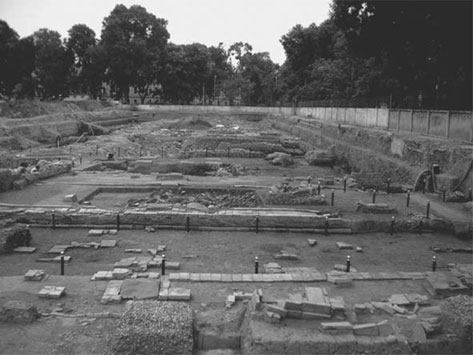

Figure 13.1 Archaeological site at the Thang Long Citadel in Hanoi (Photo C. Long)

13

Modernity, Socialism and Heritage in Asia

In the rugged mountains in the northeast of Laos, close to the Vietnamese border, the Vieng Xay Caves are being transformed into a tourist attraction. During the 1960s and 1970s these caves served as the base area for the Lao communist movement, the Pathet Lao. Today they are the centrepiece for a tourism development strategy designed to alleviate poverty in one of the poorest parts of this very poor nation. I have been integrally involved in the project, especially in the interpretation of the site and the management of its artefact collections. In the process, I have come to understand the complex place of heritage in communist states. Heritage – of both the non-communist and communist periods – is bound up in processes of political and ideological legitimation and economic development in ways that have some parallels to the incorporation of it into the national project in more plural societies, but also in ways that are unique to communist states. To understand the role of heritage in communist states, it is necessary to acknowledge the deeply ideological nature of officially endorsed heritage in all societies – in the sense that official heritage expresses the cultural, social and political beliefs of the politically powerful. It is thus necessary to understand the way that communist ideology interacts with the main currencies of heritage – the past, modernity and development.

Working in Vieng Xay also alerted me to the importance of understanding the diversity of communist experience. For much of the time since the Bolshevik Revolution, there has been a tendency in the non-communist world to see communism as monolithic and totalitarian. This was always an oversimplification that hampered rather than helped understanding even in the USSR and Eastern Europe. It was far from helpful in Asia, where the communist experience differed substantially from Europe and even between the individual communist states of Asia. This chapter, then, seeks to explore the interaction between communism as an ideological form with particular approaches to the past and heritage as a way of interpreting and remembering the past for today’s and future purposes, taking account of the particular historical and political circumstances of the three states that constitute my case studies.

There is a growing interest in the heritage of socialism 1 in those countries that have experienced communist pasts, whether Communist Party rule has ended or continues. This interest is particularly strong in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (see, for instance, Light et al. 2009; Hall 2001) and, perhaps to a lesser extent, in the countries that made up the Soviet Union (Boym 2001; Kliems and Dmitrieva 2010; Sezneva 2002). Given the pressing need to negotiate new personal, local and national identities in the wake of communism; the lustration imperatives in nations that experienced substantial repression; the accessibility of previously closed archives; the increased openness of formerly closed societies, and the new diversity of public views; and the pressing need for new strategies of economic development, including heritage tourism (see Wang, Chapter 14 in this volume), the ferment around socialist heritage is understandable. Common to these societies is a fairly clear sense that the socialist period was a distinct period of time that is now in the past, with an end date somewhere between 1989 and 1991. This is not to say that legacies of socialism do not remain – they clearly do, both tangibly (for instance as buildings) and intangibly (as ways of thinking and doing things, even in relations between different social and ethnic groups).

However, the situation is more complex in those societies that remain under the rule of communist parties, including China, Vietnam and Laos.2 In many ways, the analysis of the treatment of socialist heritage in these countries is more complex than in any of the others precisely because they are hybrids: essentially capitalist economies overseen by communist parties.3 Many of the reasons for the interest in socialist heritage in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, thus, do not apply in the remaining Asian communist states. Lustration is not even vaguely on the agenda, controls on information remain tight, public views limited. However, identities at all levels – particularly national – are in ferment (a phenomenon not at all confined to these states in the present moment) and pressures for economic development are strong, entailing a dramatic opening up to tourism amongst other strategies.

This renders many of the usual academic approaches to the study of socialist heritage of only limited value in the Asian cases, especially approaches that examine socialist heritage through the lens of tourism studies (see Henderson 2007; Light et al. 2009; Hall 2001). One of the points of this chapter is to make the case for the study of socialist heritage in China, Vietnam and Laos as a way of understanding these societies and the evolution and present day reality of their political systems. To consider the place of socialist heritage in those nations of Asia in which the communist parties still hold power is to understand both contemporary strategies of development, tourism and commemoration and the historical and contemporary place of socialism in these societies.

The Distinctiveness of Asian Communism

There has always been more than a hint of Eurocentrism to analyses of communism, the Cold War struggle in which it represented one-half of the ideological divide and its ‘demise’ between 1989 and 1991. Much of the discourse about communism in Asia has always had a rather uncomfortable orientialist feel to it, seeing it as little more than a foreign implant. For some opponents of Asia’s communist regimes, communism was, thus, imposed by outsiders or their local stooges, trampling on national traditions and identities (thus communism played, in their minds, a similar role, although the terms of geographical threat were reversed, to the role it played for the right wing in 1930s Europe, which warned against Bolshevism as an ‘Asiatic barbarism’). Thus, for most writers and for a good number of American politicians, ever since he was identified as the leader of the Vietnamese independence movement at the end of the Second World War, Ho Chi Minh was either a Vietnamese nationalist or a communist – few could conceive of him as legitimately both.

Similarly the very idea of the Cold War – a conflict fought without actual military clashes with its front line at the Berlin Wall – ignores the reality that for many in Asia and other parts of the world, such as Southern Africa, the war got very hot indeed. And, as Anderson (2010: 59–60) writes, twenty years after the collapse of the Soviet Union the summary ‘the collapse of communism’ looks a little simplistic: ‘viewed in one light, communism has not just survived, but become the success story of the age’. Of course such a view raises numerous questions about what communism might mean in the Chinese or Vietnamese or Lao context. Can China, a state with fewer social protections than the US, and where getting wealthy is encouraged as a moral strength by the Communist Party leadership, be really considered communist? Certainly the state has a more active role in the economy in the Asian communist countries than in western capitalist ones, but it is in the forms of political organisation that China, Vietnam and Laos remain categorically identifiable as remnant Leninist states. However, it is not my purpose here to discuss the extent to which these countries can be meaningfully categorised as socialist or communist. My point is that we need, at the outset, to be careful to understand the distinctiveness of communism in Asia – indeed, its distinctiveness in each of the three states that are the focus of this chapter – and to understand it in its social, cultural and political context. Only with such an understanding can we comprehend the way that communism is treated as heritage and the function that communist heritage plays in these contemporary societies.

Just as it is misleading to see communism in Asia as the imposition of an alien culture, it would be unwise to ignore the very real sense in which Asian communists – especially during the revolutionary period itself – saw themselves as part of an international movement whose ideological and organisational heartland was in Soviet Russia. Particularly in their early days, the socialist states of Asia drew on the Soviet Union for models of political and economic organisation in very direct ways. Even today, the form of the Party and its role in the political structure are identifiably Leninist. Yet in China, Maoism came to represent a legitimate alternative ideological and organisational philosophy to that emanating directly from the USSR. Maoism had more limited influence in Vietnam and Laos, where Soviet ideas remained strong and where the Parties were loath to emulate the radicalism of their Chinese comrades. The do-or-die struggle of Vietnam’s and to a lesser extent Laos’ communists with the Americans throughout the 1960s and much of the 1970s – the period of the greatest destructive radicalism in China – helps to explain the relatively restrained nature of their transformations: North Vietnam simply could not afford the great disruptions of a Cultural Revolution or Great Leap Forward when it was engaged in full-scale conflict with the US.

Nevertheless, despite their diversity, there are some broadly shared characteristics of the socialist revolutions in the Asian communist states that mark them out as distinctive from the socialist states of Russia and Eastern Europe, and which continue to condition attitudes to and understandings of socialism in them. First, central to Maoism and the strategies of the Asian Parties, was the recognition by the communists that they needed to win the support of the peasantry, which made up the vast majority of the population. Lenin’s Bolsheviks had always distrusted the peasantry and much of the first two decades of Soviet history consists of a virtual war against it, from which the Russian countryside never recovered. In contrast, the Asian socialist revolutions were built on the support of the peasantry, an inevitability given the small size and lack of political development of the urban working class. In Vietnam, and even more in Laos, the communists cultivated support among ethnic minority groups that had been historically marginalised by both colonial and indigenous elites, although the relationship between the communist regimes and ethnic minorities has, in the post-revolutionary period, become more complex, with tensions over land rights, concepts of national unity and identity, and attitudes to culture, traditions and modernity.

Second, but no less important, the Asian communist revolutions were legitimately nationalist events in a way that the Bolshevik Revolution was not. The Soviet state eventually developed a substantial chauvinism, but nationalism was not an important element of the revolutionary program or ideology in its early days. The Central and Eastern European states remained until their final days cursed by their original sin: there, the communist parties – except for Yugoslavia and Albania – came to power only with the brutal assistance of the Red Army, and could, with substantial justification, be portrayed by their opponents as the local dupes of an aggressive and alien power. In contrast, a major element of the communist claim to legitimacy in the Asian states was, and remains, their leading role in the recovery of national independence and integrity after the years of national shame represented by the colonial period or Japanese occupation. Anti-colonialism and the defence of national independence remain major sources of communist legitimacy in China, Vietnam and Laos, and thus, important elements of the heritage domain. Indeed, as I shall discuss later, the intersection of heritage, nationalism and communism is a fluid, vital space in these societies today.

Communism and Modernity

While there are very important ways in which the Asian communist regimes are distinctive from the Soviet model, there are some fundamental consistencies of particular relevance to us here. Marxism drew heavily on enlightenment concepts of progress, reason and science. All Marxist regimes have had pretensions to be engaged in the realisation of scientific principles of historical change, moving towards the historically inevitable development of a communist society. This was one of the sources of the radical brutality of communist regimes: convinced of the rightness of their understanding of the ‘laws’ of human development and of their role in leading the forces of progress, communists saw all those who held alternative views, even if only moderately incompatible, as standing in the way of the realisation of an ideal society whose eventual existence was a given. The strength of communist ideas of historic inevitability and the justice of their vision made them lethally impatient with resistance or even difference.

The undeniable fact of the enlightenment origins of communism does not render it an imported concept in the Asian societies in which it took root so successfully. Nevertheless, a valid question remains: how did communism ‘fit’ with local traditions of social and historical development? And, flowing from this, how does communism fit in with traditional understandings of heritage and culture in Asia?

Despite its emphasis on internationalism, Marxism became the ideology of choice for many nationalists in the twentieth century. Ho Chi Minh, of course, was attracted to it after reading Lenin’s Theses on the Colonial Question while living in Paris. Lenin’s innovation was to see the struggle of colonised nations against their imperial oppressors as fundamental to the broader struggle of the working masses against capitalism. Metropolitan capitalism was, he argued, dependent on its ability to exploit the colonies and the metropolitan working class could not expect true liberation without the national and social liberation of the colonies. Thus, he saw that the first stage in the revolutionary process in the colonies would involve a struggle for national independence, in which communists would take important, but probably not exclusive, roles (Ho Chi Minh 2007). Marxism became entirely compatible, indeed inseparable from, the fight for independence in the minds of Asian revolutionaries. In fact, Marxism enabled some Vietnamese, Chinese and Lao intellectuals to deal with the shattering disruption of colonialism, helping to restore a sense of meaning and narrative direction that their societies once possessed but which had been lost as a result of European intrusion. The description of capitalist modernity provided by Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto – ‘all fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify’ – must surely have struck a powerful chord among Asian intellectuals in the years after World War I. We are entirely familiar today with the postmodern critique of the ‘totalising grand narrative’ of Marxism, but this was precisely what was attractive about it to its adherents, as Menand (2003: xv) writes:

Marxism gave a meaning to modernity. It said that, wittingly or not, the individual performs a role in a drama that has a shape and a goal, a trajectory, and that modernity will turn out to be just one act in that drama. Historical change is not arbitrary. It is generated by class conflict; it is faithful to an inner logic; it points toward an end, which is the establishment of the classless society. Marxism was founded on an appeal for social justice, but there were many forms that such an appeal might have taken. Its deeper attraction was the discovery of meaning, a meaning in which human beings might participate, in history itself.

Marxism may radiate a distinctly Enlightenment teleological vision but it found, in China and Vietnam in particular, soil fertilised with a need for a new understanding to replace the traditional verities – in Vietnam and China the Confucian worldview – that had been shattered with the ‘feudal’ monarchies. Marxism promised to give intellectuals and revolutionaries an active role in the formation of new national identities and societal trajectories instead of the role of passive natives or collaborators in the imposition of colonial modernity.

Communism and the Past

Marxism, in other words, enabled Asian revolutionaries to break with the past. This is an important point. In recent years, certainly since the concerted economic liberalisation in China, Vietnam and Laos, the Communist Parties have sought to portray themselves as defenders of ancient national traditions. We will return to this later, but for now we should note that in their revolutionary days the Parties had, at best, an equivocal attitude to the past. In some instances there was an effort to reclaim authentic traditions of the people, ‘untainted by colonialism, finding, as it were, the authentic […] essence that would be a source of national pride’ (Ninh 2002: 173). Perhaps more common was the attitude expressed in the Vietnamese pamphlet, A New Culture, written just before the August Revolution, but popularised after it, and published by the Cultural Association for National Salvation (a Viet Minh organisation):

As in other spheres, the task of construction in the cultural arena has to begin with destruction: for a new culture to develop, it needs a cleared piece of land that contains no outdated or colonial vestiges. Therefore, the first task is to completely eradicate the poisonous venom of the feudalists and colonialists.

(cited in Ninh 2002: 63)

Yet revolutionary regimes also have a powerful reliance on history as part of their claim for legitimacy. For the seizure of power to be more than just an usurpation, the revolutionaries must be able to portray their act as both necessary and in accordance with the wishes and interests of the masses. During the revolutionary period itself, this might entail a breach with the past – a rejection of the corrupted, illegitimate ancien régime. However, in the long term, efforts are made to establish links with a purer past, an uncorrupted proto-revolutionary tradition. It is for this reason that history itself and its instrumentalisation as heritage have been of such vital, but problematic, importance to communist regimes. In many cases when events turned out a different way to how the ideology presumed they would, the record of those events was written, or altered, to suit political needs rather than reality (for an excellent exploration of this process in the Vietnamese context see Giebel 2004). All political regimes seek to shape and influence the historical record, the national story and identity, very often using heritage preservation strategies as one means of doing so. Communist regimes, however, have had a greater political will – the need to fit the revolutionary project into a Marxist teleology – and means – total, or approximating total, control over the cultural and intellectual means of production – to do so.

The relationship between history/historiography and heritage is always complex, even more so in Vietnam, Laos and China because historiography is officially constrained and there is an official version of history. In the Party-controlled state, nearly all heritage, as with most history, has a political significance beyond what it is expected to have in more pluralist societies (where heritage, nevertheless, still frequently serves a political purpose).

In any country, particularly in communist countries where control over the interpretation of the past is subject to substantial political influence, historiography has an important influence over conceptions of heritage. In Vietnam, China and Laos, official historiography is heavily politicised, although this is slowly changing (Stuart-Fox 2003; Evans 2003; Goscha and Ivarsson 2003; for an example of the official historiography see Communist Party of Vietnam 2005: Ch. 1). The historiographies of these countries can be broadly characterised as shaped by a form of vulgar Marxism, with heavy emphasis on class struggle; the doctrinaire use of concepts such as feudalism, reaction and resistance; efforts to establish a long lineage of nationalism and proto-revolutionary movements; and an attempt to combine nationalism and proletarian internationalism (including an effort to link their own revolutions with the Russian revolution of 1917; see Giebel 2004). It is this basic framework that continues to shape the official worldview of historians from these countries, the official discourse on history and, hence, the discourse on heritage.

Communism and Heritage

The treatment of communist heritage is a different question to the treatment of heritage under communist regimes, although the two are clearly linked. Before turning to communist heritage itself, I want to first briefly examine what role heritage plays in the communist regimes with which we are concerned.

Some of the uses of heritage by communist regimes differ little, or only in degree, from the way it is used by other political regimes, including liberal democratic ones. In other cases, there are particular characteristics of communist systems – and, moreover, particular communist nations – that give it a distinctive nature. As suggested earlier, revolutionary regimes must be able to portray themselves as at the least a historical necessity, even if popular support is reluctant. In the case of China, Vietnam and Laos, revolutionary legitimacy was initially based on the communist promise of social justice and social revolution, and more definitively in the latter two countries, on communist leadership of the national independence struggle (even in China, where the communists’ main enemy was an indigenous nationalist organisation, Mao’s forces were able to portray themselves as the more determined and successful of the anti-Japanese resistance forces during the 1930s and 1940s, and the more likely to restore and defend Chinese national integrity). At present, none of these regimes is in any meaningful sense engaged in the ‘construction of socialism’, and, having achieved the goal of winning and consolidating independence, there is no outside enemy to present an immediate threat. Thus, the two primary sources of their legitimacy are now largely no longer effective. The fundamental problem for regimes such as these is the extent of the claims that they make: the Party is the leading force, the historically ordained organisation guiding the people towards a happy future. However, if the Party ‘is in total control then it is also responsible for everything’ (Confino 2008: 143). In political systems where legitimacy is more organically derived, processes of legitimation are more subtle and political parties need to spend little time on justifying the system itself. Having claimed sole right to political power, communist regimes, on the other hand, find themselves constantly having to justify that monopoly and the system that enshrines it. Since the end of the period of ‘socialist construction’ and the defeat of external (and, to a considerable extent, internal) threats, regime legitimacy has been dependent on continual economic growth to improve living standards and on the association of communism with national independence and the preservation of traditional culture – indeed, especially in China, with its growing sense of nationalist assertiveness (as discussed in Ai’s chapter, this volume).

Heritage has been important to both these legitimacy strategies. The primary way in which it has been integrated into the program of economic growth is through tourism. Tourism is an important source of foreign exchange for Vietnam and Laos – the latter in particular – and a growing source of income for China. Cultural heritage is employed as an important component of tourism strategies in all three countries. In Laos, the World Heritage site Luang Prabang is now widely known around the globe for its charming streetscapes and Buddhist and royal legacies and is a centrepiece of Lao tourism marketing (Long and Sweet 2006; Dearborn and Stallmeyer 2010). In Vietnam, culture – such as intangible culture, for example, music, as well as the cultural practices of ethnic minority groups – is central to the national tourism strategy. Vietnam, like Laos and many other states, has realised the tourism potential of World Heritage sites and is enthusiastically adding to its list of sites (the Thang Long Citadel in Hanoi was added to the list in 2010).

Breidenbach and Nyıri (2007) show that Chinese official policy towards World Heritage tends to see it as a form of advertising for tourism development. Chinese World Heritage sites, they argue, are heavily managed by the Chinese authorities, not so much to preserve their cultural and natural values, but to maximise the economic benefits and to mold ‘local ways of life into the national development ideal’ (Breidenbach and Nyıri 2007: 326). In China, tourism is seen as a low-cost development option for poor regions and World Heritage – heritage of all kinds – is seen as a resource for such tourism.

In all three countries, heritage is brought into the national project not as backward-looking nostalgia or as a form of defensive identity preservation, but as an assertion of national dynamism and pride. Heritage, in its many forms, is incorporated into the national development narrative as the recuperation of worthy national traditions that had been suppressed or damaged during years of colonial and neocolonial intervention. Heritage – particularly World Heritage listing – is seen not as a form of preservation against the depredations of ‘development’ but as a resource for a nationally grounded, distinctive (hence marketable) development program:

the traditionalizing frame [the use of traditional narratives to interpret heritage sites] operates in the service of a radically future-oriented message: China is modern and powerful; after decades of isolation and backwardness it stands today on the world stage as an equal player […] Endorsement by UNESCO is seen as a token of China’s belonging to the world and to that end, not only locals but also tourists are subjected to the civilizing mission. The exhortation on the Jiuzhaigou ticket to ‘be civilized tourists’, repeated on signs and by guides, echoes Sichuan Tourism Bureau Deputy Director Zhang Gu’s declaration that ‘the construction of scenic spots and scenic areas must both fully reflect modern material civilization and fully display the positive and advancing spiritual civilization of the Chinese race’.

(Breidenback and Nyıri 2007: 328)

Of course every heritage narrative excludes at the same time as it includes, and for communist regimes, the mechanisms and motivations for the control of the narrative are generally more powerful than in more pluralist societies. Economic development is a powerful source of regime legitimacy and heritage can be incorporated into development programs through tourism, as I have argued. However, there remains the imperative to ensure that the heritage fits into the accepted national narrative and this is sometimes a difficult negotiation. As I have argued elsewhere (Long 2003), when Vietnam was successful in getting the former royal capital, Hue, on the World Heritage list in 1993 it was forced to reassess its attitude to the ‘feudal’ past, modifying the doctrinaire assessment of the Nguyen dynasty that built Hue – a dynasty that was portrayed as consisting of reactionary feudalists who had not only repressed the population, but also had been unable to defend the nation from the French colonialists – to recuperate a sense of Vietnamese civilisational achievement manifested in the beauty of Hue’s imperial monuments. It was the employment of a technocratic language of heritage practice – validated and given authority by the World Heritage system – that enabled this recuperation and shifting of heritage meaning.

A similar process is occurring today with the nomination for World Heritage listing of the Thang Long Citadel in Hanoi.4 This extraordinary site in the centre of the city dates back over more than 1300 years, the archaeological layers revealing the early Chinese presence in the area and the succession of Vietnamese dynasties, while the remaining architectural vestiges speaks of the Nguyen, French and post-colonial eras. Balancing claims for significance at both a national and universal level is never simple (Askew 2010; Beazley 2010). The significance values that resonate at a national level are not always of outstanding universal significance, as is required for a site to be added to the World Heritage list. In the Thang Long case, the process of nominating it for World Heritage listing meant that its significance values – primarily to do with its longevity as the political power centre of the nation and a place where cultural interchange was manifested in architecture, built form and the plastic arts – needed to be interpreted through a universal lens. As in Hue, this enabled the recuperation of otherwise historically and ideologically awkward periods – feudalism, colonialism – as elements of the long narrative of Vietnamese civilisation culminating in the modern, independent and confident Vietnamese state under the rule of the only force able to unite the nation, draw on historic precedents of national independence and protect its cultural traditions – the Vietnamese Communist Party.

Figure 13.1 Archaeological site at the Thang Long Citadel in Hanoi (Photo C. Long)

Figure 13.2 French-era building within the Thang Long Citadel, used as the Headquarters of the North Vietnamese Army during the war against the USA and its allies. Beneath it is a bunker and meeting rooms of the Army High Command (Photo C. Long)

While these World Heritage listings have enabled the redemption of some elements of the past, this is possible because the social, economic and political power structures of which they are a manifestation are historic – that is, feudalism and colonialism can be safely incorporated in a heritage narrative because they are ‘dead’. More problematic are the cultural traditions and heritages of living cultures outside the mainstream narrative, especially those of minority groups. Communism’s claims to universality are contradictory to many local cultural expressions, particularly those relating to religion or ‘superstition’ (see related discussion in Byrne, Chapter 19 in this volume). In particular, communism claims scientific rationality as a basis of progress and has little time for what it considers to be ‘unscientific’ rituals (Long 2003).

One common explanation for the success of nationalist forces in the post-Second World War anti-colonial struggles was their ability to appeal to local heritage and traditions. Such an interpretation was understandable at the height of the nationalist struggles because there was a presumption – by no means reinforced by the actual pronouncements of nationalists themselves – that those defending or reclaiming national independence must be cultural nationalists as well. This view, at least as it applied to the nations under examination here, was far from accurate, tending to emphasise the nationalist over the revolutionary aspects of the movements. While nationalism played an important role in Asian revolutionary movements, they all sought and embarked upon radical social, political and economic change as well. These states were not in the Singaporean or Malaysian mould: part of the reason why they have not been major advocates of the ‘Asian Values’ ideology espoused by Lee Kuan Yew or Mahathir Mohammed.

Kim Ninh questions the usual analysis of the success of the Vietnamese communists, the ‘continuity thesis’, which posits that the success was due to the Communists’ ability to harness the ‘traditional strengths of a country that possessed an ancient civilization and a strong sense of national identity. In this view, the communists’ ability to take control of the nationalist movement was due to their success in representing the needs of the bulk of the population within a political vision that deeply appreciated the influence of the past upon the present as well as the future’ (Ninh 2002: 238). Instead, Ninh argues that:

the powerful moment of unity between the communists and many within the intellectual community […] was not in the preservation of the nation’s past and cultural achievements but in their very destruction in order for a new Vietnam to emerge into the modern world. Far from the discourse of historical continuity and national confidence with which we have become familiar, what I want to draw out is the profound ambivalence about the worth of national culture that pervaded not only the intellectual community but important Party writings on cultural and intellectual issues.

(ibid.: 240)

What is striking, then, about contemporary official attitudes to heritage in Vietnam is the extent to which this ambivalence about the worth of the past is being resolved and the extent to which the disjuncture with the past that was cultivated in the early revolutionary years has been rejected, with a new emphasis on historical continuity. Something similar is going on in Laos and China, I would argue. In the former, historiography and heritage policy – especially as manifested in the National Museum in Vientiane and in recent archaeological research – are geared towards pushing back the timelines of the emergence of a distinctive Lao ‘nation’ (Pholsena 2006: Ch. 4), part of the effort of the contemporary Lao state to ‘write an autonomous history against foreign influences’ (ibid.: 102).

In China, communist historiography initially emphasised struggle and rejection of the past. There was some variation within this – for instance, Mao’s incorporation of elements of China’s ‘glorious ancient culture’ during the 1940s United Front period (Whitmore 1980: 25) and some increase in nationalism after the Sino-Soviet split. However, in general, Mao advocated a doctrinaire understanding based on struggle and the distinctiveness between the communist period and the feudal past. Today, though, as China becomes more confident of its global power, more assertive and more important on the global stage, it has become much more nationalistic. In addition, socialist rhetoric appears rather anachronistic on the world stage, whereas nationalism is a truly global language. China is concerned, too, to overcome its history of national subservience, as part of a broader civilisational challenge to western dominance.

Official attitudes to the past, including approaches to heritage, then, have shifted from the revolutionary emphasis on disjuncture from the backward and shameful past as part of the effort to create a new socialist society, to more purely nationalistic narratives emphasising continuity with valued national traditions. Along with developmental objectives designed to produce economic growth (including heritage tourism strategies), the idea of the Party as the defender of national traditions is a crucial element of the claim to legitimacy in the post-socialist moment. That these three states now feel it necessary to portray themselves as defenders of ancient national traditions indicates, just as much as the shift to the free market, the extent to which the revolutionary project has in fact lapsed, perhaps even failed. Indeed, we might argue with Žižek (2009: 132), that the erasure of cultural traditions that accompanied the initial revolutionary upheavals, especially during the Cultural Revolution in China, helped pave the way for ‘the ensuing capitalist explosion’.

Communist Heritage

It remains for us now to examine how socialist heritage itself fits into this broader context of heritage in Vietnam, China and Laos. Heritage is of vital importance in countries transitioning from socialism because new identities are being forged and new national stories are being created. Similarly, heritage has been of vital importance in the post-colonial world because post-colonial nations have had to forge new identities after the colonial period. In the post-colonial socialist countries, it was the communist party that took the lead role in shaping new identities in the immediate aftermath of the defeat of colonialism, but today there are new pressures and new influences as populations are exposed to global media and the old socialist verities lose their traction. The enormous increase in personal opportunities for many people in countries like Vietnam, Laos and China as a result of modernisation, population shifts, the relaxing of communist socialisation efforts (no one is trying to create the socialist ‘new man’ any more), the shift to market economies, demographic changes (Vietnam in particular had a baby boom after the war, giving it today a large population of young people with no direct experience of the struggles for socialism and independence), the influence of new media and global youth and consumer culture, means that new personal identities are having to be forged as well. Major international corporations view the populations of Asia, particularly China and Vietnam, as fantastic markets with enormous scope for growth – great effort is being put into advertising and creating the same kind of consumer culture that exists in the developed capitalist nations such as those in Western Europe, the USA, Japan and Australia. The changing demographics of international tourism are also shaping the way countries view their heritage and culture as a tourist attraction (Winter 2010). The rapid growth of tourism from Asian countries (in particular China and South Korea) is already shaping the tourism industry in the countries of Southeast Asia, such as Vietnam and Laos (ibid.). Growing numbers of Chinese tourists are also being exposed to the tourism offerings of Europe, Australia and the USA. For all of these reasons, heritage is a vital part of contemporary discourses on identity, while there is also considerable pressure to make sure that heritage protection does not get in the way of progress and change. It is this dynamic context in which we have to consider socialist heritage.

For all the reality of market liberalisation and the corrosive effect of capitalism on traditions and non-commodified cultural expressions, it would be a serious mistake to assume that economic reform in Vietnam, Laos and China has led to the abandonment of the ideological sphere by the Communist Party. The heritage of the socialist period is caught up in a long-term process of identity formation in formerly colonised states. The chief heritage goal of the current regimes is to portray Party rule as the force that has allowed the reclamation of the historical and cultural essence of these nations after the destructive hiatus of colonialism and western intervention. As we have seen, this is not necessarily how it was in the early revolutionary years, when a revolutionary disjuncture with the past was emphasised. However, heritage remains firmly within the sphere of state interest. This is not to say that it remains exclusively the domain of the state. Indeed, in her analysis of the transformation of Vietnamese war memorials – martyr temples, more accurately – Schwenkel (2009: 136) argues that ‘state and non-state memory work […] inform and constitute one another in particular communal and state sites of memory’. She shows how secular state recollection of the war dead, aimed at reinforcing and remembering sacrifice and dedication to the nation, is in recent years being supplemented – not replaced – by ‘intensified family and community practices’ that see the war dead as ‘venerated souls in need of ritual care’ (ibid.).

Similarly, Schwenkel (2009: 128) argues that rejection of socialist-era monuments in Vietnam by some of the younger generation

should not be read as a call for a new political regime or a rejection of official historical memory. It is rather an appeal for a new regime of representation that reproduces and conveys similar visual knowledge and narratives of the past […] but through very different iconography and aesthetics.

This desire for a new iconography and aesthetics plays out in different ways both within and between individual countries. In Vietnam, there has been a substantial effort to render Vietnamese war memorials, for instance, more ‘traditional’, more Vietnamese and, hence, less ‘foreign’, with architects adding ‘cultural icons to standard obelisk designs, including dragons, lotuses, bronze drums, or crowns resembling sloped pagoda rooftops’ (Schwenkel 2009: 130). In other cases, obelisks have been replaced by traditional temple-style structures. In Laos, the trend towards a more ‘Lao’ style of architecture – as distinct from a socialist international style – began with the construction of the National Assembly building in 1990, and continues to be reflected in the sweeping roofs and prominent use of naga motifs in most subsequent institutional – particularly museum – buildings, including the Kaysone Phomvihane Museum and the Army Museum in Vientiane (Askew et al. 2007: Ch. 7).

Similarly in China the shift away from more traditional communist monuments to contemporary architectural expressions of a global aesthetic – most clearly expressed in the edifices constructed for the Beijing Olympics – is not a rejection of the power of the current regime, but a transformation of its aesthetic manifestation. However, it is not a transformation that entirely elides the aesthetic manifestations of socialism. The emphasis of contemporary Chinese urbanism is firmly on size, power and the spectacular, a reflection in many ways of the priorities of the contemporary communist state. The state uses nationalism to boost its legitimacy and to protect itself from internal and external criticism. China’s heritage is being mobilised for the same purpose, including its socialist monumental heritage in places like Tiananmen Square. The monumental architecture of socialism – so long as it reflects these values – can be easily incorporated into the nationalist spectacular.

While the shifting aesthetic expression of nationalism leaves some space for the incorporation of the monumental manifestations of socialism, the lapsing of the commitment to create the ‘new socialist man’ in the face of the growth of the new capitalist consumer – especially in China and Vietnam5 – has also not entirely seen the abandonment of efforts to encourage ideological rectitude or good citizenship. In Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh has for a long time served as a moral example, used by the Party to exhort people to lead useful lives. The idea that the Party would create a ‘socialist man’ has largely been abandoned, but not the idea that the Party can shape a particular kind of citizen – Ho is the model of this particular citizen and diverse artistic forms are used to promote it, including operas and music. The Party paper, Nhan Dan, reveals an eclectic mix of cultural events: various celebrations of traditional cultural practices, memorial events to kings, commemorative activities about Ho Chi Minh, and in 2010, several events commemorating anniversaries of the recognition of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1950 by countries including North Korea.

Figure 13.3 Socialist realist sculpture outside the Mausoleum of Mao Tse Tung in Beijing (Photo C. Long)

Most of the Asian socialist states did not have highly developed tourism industries during the years of socialism. This is because they were ideologically suspicious of visitors from nonsocialist states, or were engaged in warfare for much of the time (Vietnam and Laos) or had virtually no demand for domestic tourism because of the poverty of their populations. From 1954 until 1979, only 125,000 visitors used the Chinese state travel organisation to visit the country (Hall 2001: 95). However, just as Light et al. (2009) argue was the case in Central and Eastern Europe during the socialist period, there has been some use of major places of communist commemoration in a rudimentary domestic heritage tourism process: for instance the mausoleum of Mao Tse Tung in Beijing, Ho Chi Minh’s mausoleum, house and museum in Hanoi, various military and revolutionary museums throughout Vietnam and China, the Kaysone Phomvihane museum and house in Vientiane, the new Army Museum in Vientiane and the Vieng Xay Caves in northern Laos. In all of these cases the state organises school trips, subsidised excursions and organised visits ‘as a means of developing social integration, patriotism, and support for the communist ideal’ (Light et al. 2009: 230). Foreign tourists are also encouraged to visit these places and do so in large numbers. Mao’s and Ho’s mausoleums are particularly well visited. Visits to them are carefully stage managed by the local authorities to create a sense of awe and reverence that reinforces the power and legitimacy of the communist regime.

It is worth noting that in Vietnam and Laos at least there is a heavy emphasis on the domestic spaces of great leaders as heritage sites. Ho’s stilt house is an extremely important site for tourists and Kaysone has two sites to visit – one in Vientiane and one in Vieng Xay. Prince Souphannouvong is similarly commemorated in Vientiane and Vieng Xay. In all these places ordinary domestic objects like clothing and shoes, radios, furniture are given pride of place, alongside books and other elements of ideological struggle and evidence of their former occupiers’ revolutionary lives. What is important here is to show that these leaders lived lives that were not radically divorced from the lives of the people (and indeed they did live rather modest lives, unlike Mao or many contemporary leaders). There is a heavy emphasis on modesty, struggle and privation: the leaders are portrayed as first among equals. Such house museums also draw heavily on cultural traits common in Vietnam and Laos of respect for elders, and especially in Laos, there is a strong quasi-religious element to adulation of communist leaders (the former Central Committee meeting room outside Kaysone’s cave in Vieng Xay contains a bust of the leader shrouded in red with a small shrine of incense and flowers in front of it).

The use of such religious motifs in communist commemoration and the persistence of vernacular, non-state commemorative practices at war memorials, as discussed earlier, suggest that there are limitations on the ‘totalitarian’ pretensions of communist regimes. Communist regimes may seek to control all political, cultural and social expressions, but they seldom actually do. Today, when the conditions for such control are less favourable than ever thanks to economic liberalisation and growing global integration and exchange of information, communist governments must seek some accommodation with traditional forms of cultural expression, such as religion. In Laos, the government has tolerated Buddhism for most of the revolutionary period and now draws on it explicitly for legitimacy (Evans 2003) while at the same time ensuring it maintains supervision over the Buddhist hierarchy. In Vietnam, there is a growing religious tolerance, although this quickly turns to repression when religious leaders stray from the realm of the soul to the realm of politics. Similarly, in China spiritual manifestations that acknowledge the ideological pre-eminence of the Party are accepted while those that challenge it – such as Falun Gong – can be harshly treated. In all three cases, one of the strategies for accommodation between Party and religion is the treatment of religious expressions and places as forms of heritage – elements of the past to be recuperated as far as possible into the national story. Thus, the 2003 inauguration in Vientiane of a statue to the Lao king Anou, who resisted Siamese dominance in the early nineteenth century, was dominated by elements of Buddhist kingship ceremonies, with little direct reference to the current political system (Askew et al. 2007: 204–6).

Heritage, thus, still plays an important role in the communication of ideological and exhortatory messages. In China, heritage and tourism are explicitly engaged in the creation of a national ideology emphasising patriotism and socialist rectitude. The State Council’s 2001 Notice on Further Accelerating the Development of the Tourism Industry’ calls for ‘closely connect[ing] the development of tourism with the construction of socialist spiritual civilization; cultivat[ing] superior national culture through tourist activities; [and] strengthen[ing] patriotic education’ (cited in Breidenbach and Nyıri 2007: 329). Breidenbach and Nyıri conclude:

Figure 13.4 ‘Shrine’to Kaysone Phomvihane in the Central Committee meeting room at Kaysone’s cave site in Vieng Xay (Photo C. Long)

‘This formulation reveals the combination of a belated mass-bettering socialist tourism with the ideology of modernization through consumption and the idea that the correctly framed consumption of places is an instrument of strengthening national consciousness. Hence the need to control the representation of places and to locate them in the nation’s history and the present through spatial arrangements, naming, legends, songs, and dances. No tourist site in China can have a purely local meaning.

(ibid.)

‘Red tourism’ – the increasing global interest in heritage associated with the communist past – is a widely noted phenomenon and of growing importance in the tourism markets of eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union (see Wang, Chapter 14 in this volume). In Beijing, crowds visiting Mao’s tomb wind for hundreds of meters around Tiananmen Square. Ho Chi Minh’s tomb is a major drawcard in Hanoi, while revolutionary heritage sites like the Cu Chi Tunnels near Ho Chi Minh City are integral elements of most international tourists’ itineraries (Schwenkel 2009: 88ff). Some aspects of the socialist heritage are clearly attractive to many tourists. This will ensure that at least some of it is protected and remains important in state heritage strategies. However, the popularity of Mao’s tomb raises another important issue about the role of socialist heritage in contemporary Party-run states. A very large number of the visitors to Mao’s mausoleum are Chinese. The question must inevitably arise: why is Mao still celebrated so substantially in China despite the great disasters and suffering for which he was responsible (and which many, if not most Chinese, are aware of) and despite the dramatic shift away from the Maoist vision that has taken place in China since the early 1980s? The answer is relatively simple: to abandon Mao is to call into question the Party’s legitimacy and its continued right to rule.

Red tourism in China, thus, performs the function of transforming the socialist past into a story of nationalism and nation building, while at the same time acting as a form of economic development. Branigan (2009) argues that communist heritage in China serves either to boost revenue through tourism in poor areas or else serves as a resource for the development of the ‘national ethos’. The history of communism that is portrayed in places like the former revolutionary base area of Yan’an – where daily re-enactments of battles with Chiang Kai Shek’s nationalists take place – carefully ignores the great disasters like the Great Leap Forward, emphasising instead the efforts of Mao and his comrades to build the nation (see Wang, Chapter 14 in this volume).

However, there is something more than the preservation of Party legitimacy behind the clinging, despite all the changes, to vestiges of the socialist past. Abandonment of the communist worldview in its entirety would be to abandon a narrative of progress and such a narrative is crucial in developing countries, much more so than in the developed west, where a narrative of progress is much harder to sustain in the face of the evidence of the twentieth century and where the cultural influence of postmodernism is much stronger. If the enlightenment is largely dead in the postmodern, post-industrial west, it is well and truly alive in places like China and reflected in the ideology of growth and progress; the domination of nature by humans as manifested in enormous dams; and in nationalism and the power of the nation state. In this sense, these Party-led states of Asia continue the enlightenment project of which socialism was also a symbol.

Malarney examined the transformation of traditional rituals in the early years of the Vietnamese revolution. ‘The party completely banned some rituals’, he writes,

notably communal house ceremonies or those involving attempts to contact or manipulate the spirit world, but they sought to reform those they allowed to remain. The cadres involved in reforming rituals and writing up the new ritual regulations had a very sophisticated understanding of the way in which rituals could reproduce ideas and practices unsanctioned by the party. Cadres also understood that when reforming rituals, they could not change them to such an extent that they became meaningless and people rejected them […] Thus, in reforming rituals, the general strategy employed by the party was to selectively remove certain parts, give greater emphasis or meaning to other preexisting parts, and sometimes add new components.

(2002: 63–64)

Malarney’s description of the process of ritual transformation could equally well apply to contemporary Vietnam, Laos and China. Transformations in modes of production, according to the Marxist worldview, would lead to changing ideological and cultural manifestations. This won’t necessarily be the case in contemporary China, Vietnam and Laos. Abandoning the socialist past in its entirety is to abandon any claim to legitimacy of the Party as the sole representative of the people’s interests. In the early days of the revolution, as Malarney shows, officials sometimes rejected outright earlier cultural expressions. As often as not, though, they sought to alter and reclaim them for the purposes of the Revolution. A similar process is taking place today, but it is the traditions of the Party itself, the traditional expressions of socialism, that are being changed, transformed, but ultimately – it is the Party’s hope – continued and utilised in the process of building distinctive, independent national cultures.

Notes

1 I will use the words ‘socialism’ and ‘communism’ interchangeably – no doubt to the chagrin of Marxist political scientists.

2 Here I wish to exclude North Korea, a state that indubitably grew out of the Soviet model but which appears to have transmogrified into a strange hybrid that we might characterise as paranoid Stalinist- feudalism, a state that does not approximate to any of the other remaining ‘communist’ countries or to the states of Central and Eastern Europe at the time of the collapse of their regimes. I also wish to exclude Cuba, not only for geographical reasons, but because it seems to me categorically different to China, Vietnam and Laos, the other remaining Party-ruled states, because it retains a substantial commitment to a socialist economy. In Cuba, the socialist period is certainly not the past: the revolution continues, at least for the supporters of the Party, whose numbers are not insubstantial.

3 I prefer the term ‘hybrid’ over another commonly used term to describe such states, ‘transitional’, because the latter suggests a particular trajectory, usually presumed to be towards western style liberal capitalist democracy. It is not at all clear that this is the direction in which these states are heading, or, even, that such a societal form will outlast the hybrid communist model.

4 I was involved as aUNESCO consultant engaged by the Hanoi People’s Committee to work on the nomination documents for the Citadel in 2008.

5 One manifestation of this is the rise of TV game shows like The Price is Right, shown on Vietnamese television and offering an enticing glimpse into the new world of consumer capitalism.

References

Anderson, P. (2010) ‘Two revolutions’, New Left Review, 61. Jan/Feb: 59–96.

Askew, M. (2010) ‘The magic list of global status: UNESCO, World Heritage and the agendas of states’, in S. Labadi and C. Long (eds) Heritage and Globalization, London and New York: Routledge.

Askew, M., Logan, W.S. and Long, C. (2007) Vientiane: Transformations of a Lao Landscape, London: Routledge.

Beazley, O. (2010) ‘Politics and power: the Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome) as World Heritage’, in S. Labadi and C. Long (eds) Heritage and Globalization, London and New York: Routledge.

Boym, S. (2001) The Future of Nostalgia, New York: Perseus Books.

Branigan, T. (2009) ‘Communist heritage is good for business as China prepares for 60th anniversary’, The Guardian, 27 September. Online:www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/sep/27/china-60-anniversary-communism (accessed 8 April 2010).

Breidenbach, J. and Nyıri, P. (2007) ‘“Our common heritage”: new tourist nations, post-”socialist” pedagogy and the globalization of nature’, Current Anthropology, 48.2: 322–330.

Communist Party of Vietnam (2005) Seventy-five Years of the Communist Party of Vietnam (1930–2005): A Selection of Documents from Nine Party Congresses, Ha Noi: The Gioi Publishers.

Confino, A. (2008) ‘The travels of Bettina Humpel: one Stasi file and narratives of state and self in East Germany’, in K. Pence and P. Betts (eds) Socialist Modern: East German Everyday Culture and Politics, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Dearborn, L.M. and Stallmeyer, J.C. (2010) Inconvenient Heritage: Erasure and Global Tourism in Luang Prabang, New York: Left Coast Press.

Evans, G. (2003) ‘Different paths: Lao historiography in historical perspective’, in C.E. Goscha and S. Ivarsson (eds) Contesting Visions of the Past: Lao Historiography at the Crossroads, Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies.

Giebel, C. (2004) Imagined Ancestries of Vietnamese Communism: Ton Duc Thang and the Politics of History and Memory, Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Goscha, C.E. and Ivarsson, S. (eds) (2003) Contesting Visions of the Past: Lao Historiography at the Crossroads, Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies.

Hall, D.R. (2001) ‘Tourism and development in communist and post-communist societies’, in D. Harrison (ed.) Tourism and the Less Developed World: Issues and Case Studies, Wallingford: CABI.

Henderson, J.C. (2007) ‘Communism, heritage and tourism in East Asia’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 13.3: 240–254.

Ho Chi Minh (2007) Down With Colonialism!, London: Verso.

Kliems, A. and Dmitrieva, M. (2010) The Post-Socialist City: Continuity and Change in Urban Space and Imagery, Berlin: Jovis Diskurs.

Light, D., Young, C. and Czepczynski, M. (2009) ‘Heritage tourism in Central and Eastern Europe’, in D J. Timothy, and G.P. Nyaupane (eds) Cultural Heritage and Tourism in the Developing World: A Regional Perspective, Abingdon: Routledge.

Long, C. (2003) ‘Feudalism in the service of the revolution: reclaiming heritage in Hue’, Critical Asian Studies, 35.4: 535–558.

Long, C. and Sweet, J. (2006) ‘Globalisation, nationalism and World Heritage: interpreting Luang Prabang’, Southeast Asia Research, 14.3: 445–469.

Malarney, S.K. (2002) Culture, Ritual and Revolution in Vietnam, Honolulu: University of California Press.

Menand, L. (2003) ‘Foreword’, in E. Wilson, To the Finland Station, New York: New York Review Books.

Ninh, K. (2002) A World Transformed: The Politics of Culture in Revolutionary Vietnam, 1945–1965, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Pholsena, V. (2006) Post-war Laos: the Politics of Culture, History and Identity, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Schwenkel, C. (2009) The American War in Contemporary Vietnam: Transnational Remembrance and Representation, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Sezneva, O. (2002) ‘Living in the Russian present with a German past: the problems of identity in the City of Kaliningrad’, in D. Crowley and S.E. Reid (eds) Socialist Spaces: Sites of Everyday Life in the Eastern Bloc, Oxford: Berg.

Stuart-Fox, M. (2003) ‘Historiography, power and identity: history and political legitimization in Laos’, in C.E. Goscha and S. Ivarsson (eds) Contesting Visions of the Past: Lao Historiography at the Crossroads, Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies.

Whitmore, K. (1980) ‘Communism and history in Vietnam’, in W.S. Turley (ed.) Vietnamese Communism in Comparative Perspective, Boulder: Westview Press.

Winter, T. (2010) ‘Heritage tourism: the dawn of a new era’, in S. Labadi and C. Long (eds) Heritage and Globalization, London and New York: Routledge.

Žižek, S. (2009) First as Tragedy, Then as Farce, London: Verso.