8

Rise of the Humans: Developing Your Creativity, Empathy, and Other Uniquely Human Capabilities

Key Ideas

- We need to value our own intelligence—the uniquely human ways we learn, adapt, and create new value that we call organic cognition—over artificial intelligence—what we call silicon cognition.

- As technology advances and consumes more routine work, the value of work requiring organic cognition increases. If we focus on developing uniquely human skills, we'll continue to build value for ourselves and the organizations that engage us.

- To maximize human potential, we need to put humans at the center of every value proposition, augmenting human capacity with ever more capable tools and staying mindful of those most vulnerable to technological unemployment.

Play Is the Way Forward

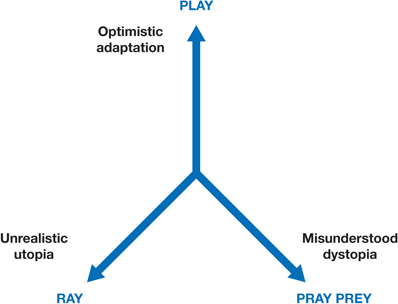

The future of work is often presented as a binary choice: a hunger game between organic and silicon cognition that results in either a dystopian nightmare in which humans fight for the last jobs not taken by robots or an nearly inconceivable utopia where artificial intelligence surpasses human intelligence, yet we bask in the leisure and self-expression afforded our newfound time free from work. Autodesk fellow Mickey McManus describes this choice as the “Ray-Pray-Play” model that perfectly captures our perspective (Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 Mickey McManus's Ray-Pray-Play

Concept credit: Mickey McManus.

Futurist Ray Kurzweil, director of engineering at Google and cofounder of Singularity University, leads the utopian charge. In his vision, we will create a massive, common, organic–silicon hybrid cognition called the singularity. While Kurzweil has proven to be prescient about many things (he enjoys an 87% accuracy rate with predictions to date), his big vision of this singularity is fraught with challenges, the most glaring of which is bias. Everyone has biases; they are the imperfect human shortcuts that allow us to quickly and even unconsciously interpret the world around us. These biases get incorporated into constructed silicon cognition, not necessarily for any malevolent purpose, but more simply because program designers don't even realize they hold a particular point of view.

Take, for example, facial recognition software. Some facial recognition software has failed spectacularly at recognizing nonwhite, nonmale faces because the algorithms and databases upon which it was based are biased by the world view of their largely white male developers.1 Biases are not necessarily racist, sexist, or otherwise bad, at least not intentionally so. They are, in all their complexity, a reflection of the experiences and perspectives of those who hold them. They are unwelcome, though, if they become codified in the systems that are meant to fairly and ubiquitously navigate the world. Biases run in every direction, but it's fair to say that we run the risk of magnifying our blind spots if we encode bias at scale.

Still, Kurzweil's utopia is the “Ray” in McManus's model.

McManus dubs the dystopian “technology eats the humans” perspective “Pray.” Indeed, there is a crowd of catastrophists predicting a future where technology consumes the majority of jobs, leaving humans scraping by on meager universal income supplements, leaving us to pray that we survive or, worse, that we don't become prey to one another and the machine.

McManus, though, adds a third perspective: “Play.” McManus and his colleagues at Autodesk believe, as do we, that humans are driven to create, explore, communicate, and learn through the acts of making and play. When we putter around making things without a clear and direct utilitarian need, often we are learning. Jazz, improvisation, analogy, metaphor, synthesis, interpretation—all of these types of creative play and learning are unique to human beings.

The idea of playful learning is especially intriguing when we think of it in the context of what makes us uniquely human. As it turns out, today's machine learning is more analogous to that of a four-legged species than it is to the human species. Let us explain.

The Uniqueness of the Human Drive to Learn and Create

Is pedagogy, the method and practice of teaching, innate to humans? Some psychologists say yes, although many biologists reject that idea. The answer, however, may lie in the definition of “teaching.” All animals learn, some through mimicry and some through guidance or behavior modification. In all species, behaviors are learned through repetition, usually for a utilitarian purpose, such as finding food rather than becoming it. Humans, though, seem special in the drive to create, explore, and synthesize information purely to expand our body of knowledge. Knowing that Zimbabwe has the most official languages—16!—may not help you secure your dinner, but it might win you a bar bet. And more than just stockpiling facts, humans seem to be distinct in their penchant to reflect on how we learn in order to improve our ability to teach others.

We turned to our stable of educators and scientists to validate or reject our theory, and we found ourselves in a long, learning-filled debate that itself validated the thesis. Lisa Rioles Collins is both a scientist and a voracious learner. When asked for her take on learning in humans versus other species, she shared these insights:

There is evidence that birds teach their young songs and that birds can learn the songs of other birds as well as other sounds. There is also evidence that birds with elaborate nests teach their young how to make those nests. There is lots of other evidence regarding “teaching” in nature. Cheetahs will bring live prey back to their cubs for them to practice killing their own prey. What I really think separates us from animals has more to do with our ability to reflect on our learning and on the learning process. We have the unique position and, thanks to modern technology, the time to sit and reflect on what we are learning, how we are learning, how we would like to learn, and how to better teach our students.

Dr. Maria Calkins, a university professor of psychology, summarizes it this way:

I think what makes us human is our ability to gain “wisdom” as well as being able to generalize learnings to new applications, which takes creativity. Human creativity involves generating original ideas, making nonlinear connections between things that are seemingly unrelated, looking at things from a variety of viewpoints, and putting ideas together in various ways to come up with something new. All of those, in my view, are unique to the human species.

Hungarian developmental psychologists György Gergely and Gergely Csibra hypothesize that humans have what they call the pedagogical learning stance, which allows an infant to retain generic information. According to their theory, human babies are able to learn information in a given instructional setting, through communication, that they can later apply to a wide range of potential new situations. “Natural pedagogy is not only the product but also one of the sources of the rich cultural heritage of our species,” Gergely and Csibra write in their 2011 paper “Natural Pedagogy as Evolutionary Adaptation.”2 They believe it is our ability as humans to accommodate that knowledge for future application that differentiates us from other animals.

With these scientists, psychologists, and educators informing our thinking, it seems that it may be our ability and inclination to continuously learn and disrupt ourselves that makes us uniquely human. No other animal species disrupts themselves by creating new innovations and new, more complex tools, and certainly not ones that threaten their very survival as a species.

Interestingly, some of what separates us from other animals is also similar to what separates us from today's artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. Silicon cognition has not been able to replicate or demonstrate innateness, that inherent sense of awareness, sentience, or wisdom found in humans. It struggles to apply learned skills and knowledge to new contexts. It simply lacks common sense. Paul Allen, cofounder of Microsoft, recently announced a $125 million investment in his AI lab called Project Alexandria with the goal of exploring how to develop “commonsense AI” because, as Oren Etzioni, a former University of Washington professor who oversees the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, says, “AI recognizes objects, but can't explain what it sees. It can't read a textbook and understand the questions in the back of the book. It is devoid of common sense.”3

DARPA has a similar initiative underway called The Machine Common Sense Program. “The absence of common sense prevents an intelligent system from understanding its world, communicating naturally with people, behaving reasonably in unforeseen situations, and learning from new experiences,” said Dave Gunning, a program manager in DARPA's Information Innovation Office (I2O). “This absence is perhaps the most significant barrier between the narrowly focused AI applications we have today and the more general AI applications we would like to create in the future.”4

In late 2019, Microsoft announced a $1 billion investment in Elon Musk's OpenAI to support building artificial general intelligence (AGI) because they believe “Modern AI systems work well for the specific problem on which they've been trained, but getting AI systems to help address some of the hardest problems facing the world today will require generalization and deep mastery of multiple AI technologies.”5

While there are many parlor tricks and even more practical examples of narrow artificial intelligence, we are a long way from achieving generalized AI despite mind-boggling investments by the likes of Microsoft to make it so. In a June 20, 2019, article for Wired, reporter Gregory Barber wrote that even as AI becomes increasingly capable of handling specific tasks, the lofty goal of general AI that easily switches among diverse tasks is still a long way off. How far? “Please don't hold your breath,” Barber wrote. “Preserve those brain cells; you'll need them to out-think the machines.”6

Or, as biologist Janine Benyus says, human cognition has benefited from “3.8 billion years of evolutionary R&D.”

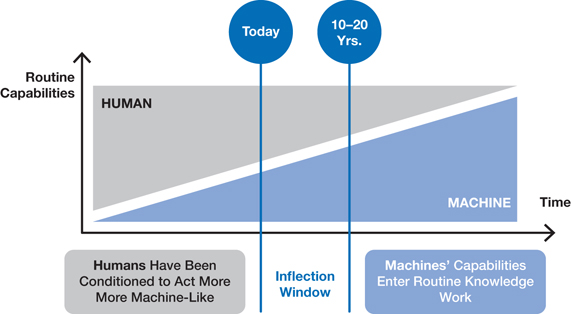

We are so focused on developing machine capabilities to perform cognitive work that we nearly fail to develop our uniquely human skills, and paradoxically we have trained humans to act more like machines. We are conditioned, for example, to respond to the stimulus of a smartphone alert and have trained ourselves to structure data in ways computers can understand. We test people on tasks that machines can do (retrieve information), rather than asking people to act more like humans (creating and collaborating). We ponder just how powerful silicon cognition can become and yet we don't even know what humans are capable of doing (Figure 8.2).

Figure 8.2 Routine Tasks—Human versus Machine Abilities

The Predictive Markets Declare Future Skills Favor Humans

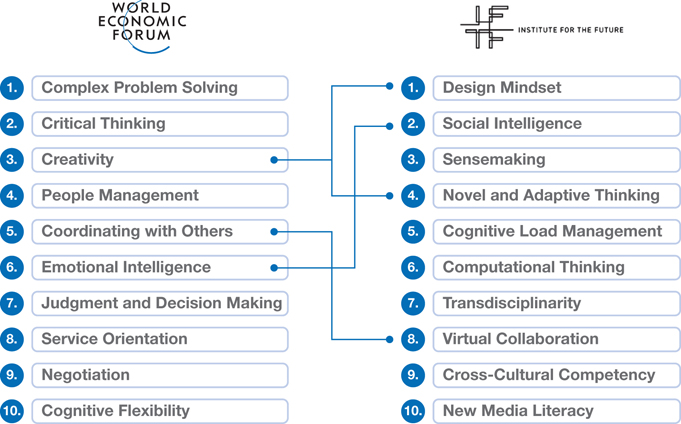

Will this uniquely human ingenuity drive us into the future? Check any list of future skills from the World Economic Forum to the Institute for the Future (Figure 8.3) and you will find one particularly intriguing similarity: none of them are specifically technical skills. The skills most needed in the future of work all center on uniquely human skills and our ability to think about our own thought processes and how we operate, and, more specifically, to collaborate with rising technology capabilities. To those we would add the ability to adapt fluidly as new data informs our surroundings. So why are so many people grasping at technology and sounding the alarm that schools need to teach more and better STEM skills, insisting that every kid must learn to code?

Figure 8.3 Future Work Skills: Institute of the Future and World Economic Forum

Data sources: Institute for the Future and World Economic Forum

Without a doubt, digital skills are important. They are, in fact, now a fundamental literacy just as are reading, writing, and the quantitative skills that involve the manipulation of numbers from math to statistics to economics to data analysis. Knowing how to code may help you get a job in coding, but, more importantly, it will help improve your logical reasoning. And, much more importantly, it will help you understand what can be coded and automated. That skill, says Dr. Randy Swearer, vice president of learning futures at Autodesk, is critical. “Humans need to understand what's computable. They don't need to understand a code, or to code, but they need to understand what's computable.”

The real advantage to digital fluency is that it enables uniquely human skills to be seamlessly augmented with technological capabilities. That empowers individuals to see what can, and perhaps should, be automated. It empowers you to see that your real value comes from your uniquely human skills—your ability to leverage the technology tool and provide the wisdom, judgment, and common sense to maximize the value you create.

Uniquely human skills. Soft skills. Nontechnical skills. Power skills. Noncognitive skills. Enablers. Whatever you decide to call them, these are the skills that are, at this point in technology's evolution, difficult for machines to achieve. In Chapter 7, we looked at the World Economic Forum's skills list focusing on individual skills. By comparison, we divide the Institute for the Future (ITF)'s Future Skills 2020 list into two camps: individual performance skills and the aptitudes that enable better human-to-human and human-to-machine collaborations. Let's take a closer look at each of these.

Individual Skills

We recognize these ITF skills to be foundational for every worker.

- Design mindset. ITF defines design mindset as the “ability to represent and develop tasks and work processes for desired outcomes.” Leaning on Heather's background and experience in design, we would extend this definition to include the ability to deal with ambiguity, focus on finding and framing challenges, and placing the human at the center in seeking novel solutions.

- Novel and adaptive thinking. ITF defines novel and adaptive thinking as “proficiency at thinking and coming up with solutions and responses beyond that which is rote or rule-based.”

- Cognitive load management. ITF defines cognitive load management as the “ability to discriminate and filter information for importance, and to understand how to maximize cognitive functioning using a variety of tools and techniques.” We can more effectively leverage these technology tools, including finding insights in data, when our own cognitive processes are not overwhelmed. And here, there is genuine reason or concern. Researcher Dr. Martin Hilbert at the University of Southern California calculated that the amount of data coming at us every day from sources as diverse as television to smartphones exploded from the equivalent of 40 newspapers a day in 1986 to as many as 174 in 2007. It's not surprising, considering the rise of social media and smartphone apps, that the number leaped to the equivalent of 280 newspapers in 2012. Imagine how high that pile of papers reaches today! Our ability to sift and filter through this data deluge will be essential for our ability to continuously adapt.

- Sensemaking. ITF defines sensemaking as the “ability to determine the deeper meaning or significance of what is being expressed.” While this is just one application of sensemaking, finding insights in analyzed data is an enormous opportunity. Soon every company will be both a data company and a learning company. To learn from data requires sensemaking to extract insights from observations that become transparent in data. According to IBM, in 2013 the world created more data than ever in human history.7 This trend in data creation is following an exponential growth curve as every connected person, every connected device, and every interaction leaves a data trail. The networking giant Cisco projected that every person will have four Internet-connected devices by 2020, up from two in 2010.8 The leading technology market research firms punctuate this projection—and the problem it creates. IDC projects growth rates for data to exceed 61% compounded annually,9 while Forrester reports that 60–73% of data is ignored today,10 presumably because we just can't process it. These trends are huge opportunities for future insights to be found by applying both data analytic skills and sensemaking.

Collaborative Skills

To be well prepared for human interaction and lay the groundwork for human-to-machine collaboration, IFT recommends we develop these skills:

- Social intelligence. ITF defines social intelligence as the “ability to connect to others in a deep and direct way, to sense and stimulate reactions and desired interactions.” We add “emotional” intelligence to this definition, adopting the guidance of author and science journalist Daniel Goleman, who believes that social and emotional intelligence comprises both self and social awareness and self- and social management. In short, his framework states that you must be aware of your own emotional reactions and responses as well as those of others before you can manage your own social responses or those of others. Social intelligence is essential for effective collaboration.

- Transdisciplinarity. ITF defines transdisciplinarity as “literacy in and ability to understand concepts across multiple disciplines.” We broaden the definition just a bit to include, specifically, the ability to set aside the tunnel vision of one discipline in order to assess the situation and fully understand the challenge from a fresh perspective. Only then can you integrate disciplines and technologies to optimally address the challenge. (See Figure 4.5 in Chapter 4 to review the I to T to X evolution toward trandisciplinarity.)

- Cross-cultural competency. ITF defines cross-cultural competency as the “ability to operate in different cultural settings.” Put another way, we need to develop a fluency of culture, much as one would a fluency of language, in order to adapt appropriately to different cultural settings. Cross-cultural competency is essential to successfully adapt in our hyperconnected and interdependent global economy in which no one culture dominates.

- Computational thinking. ITF defines computational thinking as the “ability to translate vast amounts of data into abstract concepts and to understand data-based reasoning.” Autodesk's Randy Swearer describes this skill as “not necessarily the ability to code, but the capacity to understand what can be coded or what can be computed.” Computational thinking, in the context of collaboration, is a tool to support your adoption and use of—your collaboration with—technology tools.

- New media literacy. ITF defines new media literacy as the “ability to critically assess and develop content that uses new media forms, and to leverage these media for persuasive communication.” Like computational thinking, new media literacy describes collaboration with technology tools.

- Virtual collaboration. ITF defines virtual collaboration as the “ability to work productively, drive engagement, and demonstrate presence as a member of a virtual team.” As we increasingly work on global and often virtual teams, we must hone our ability to forge new relationships with, and perhaps even lead, people we may never meet in person.

Stripping Stereotypes from Skills Categories

As we were writing this book, we needed to decide what language we wanted to use to describe uniquely human skills. We opted not to use the term “soft skills” because for many generations, the idea of “soft” and “hard” skills broke down along gender lines. Women were discouraged from pursuing the “hard” sciences thought to be the territory of men who dominated careers in mathematics, engineering, chemistry, and the like. Instead, women were ushered into the “soft” sciences such as psychology or sociology, or perhaps encouraged to skip science altogether. Perhaps worse, the “soft” skills of listening, empathy, compassion, and collaboration were relegated to women, while men did the heavy lifting of “hard” skills like competition and leadership.

These gender stereotypes have little place in the modern workforce, and not just as a matter of workforce equality. Study after study shows that a well-integrated mix of so-called hard and soft skills leads to greater professional and personal success.

For these reasons, we eschew the term “soft skills” in favor of “uniquely human skills” to capture those capabilities that enable better work and stronger relationships.

Understanding Uniquely Human Skills

In the emerging world of work, collaboration is king. According to data collected by the Harvard Business Review, in the past two decades time spent on collaborative activities at work by both managers and employees has increased by more than 50%.11 In writing this book, we spoke with Donna Patricia Eiby, creative director for the Future Work Skills Academy, a learning solutions provider formed by a global coalition of skills experts who came together to create the Future of Work Skills Academy based on the groundbreaking work by the Institute for the Future. Eiby highlighted the importance of the ITF skills:

Collaboration is the agency to deliver value through other humans or in concert with technology or a blend of both. Given the growth in both human-to-human and human-to-technology collaboration, it is not surprising that 50% of the IFTF's skills relate to collaboration. Skills requirements now move so fast in work that mastery may be a thing of the past. Instead the Generalist, as described in David Epstein's book Range, is the new normal by which we deliver value as transdisciplinary team. Therefore, effective team collaboration is mandatory in the Future or Evolution of Work.

Humans need to understand what is computable or codable for automation and the list of IFTF skills are not, at this point, automatable. I believe that the nonroutine work of humans is essentially managing friction. What does this mean? Friction is the space between you and your goals—whether that be greater sales, better solutions, happier workers, happier customers. Anything. Every organization operates in an ecosystem where the primary purpose is to identify friction between actors and their desires and then determine how to manage it. Managing doesn't mean reducing [friction]; in some cases an increase in friction, for example FOMO or Fear of Missing Out, can be a desired state. This is the work of humans and in the past, this has been the domain of only creatives, research and development, and marketing. I believe, in the evolution of work, we should see all human workers first and foremost managing friction. It is the heart and soul of nonroutine work. Can machines identify points of friction? Absolutely, if they are optimized to that goal. And in fact, AI (big data/machine learning) is a fabulous tool for identifying friction points. But it's humans who frame the problem and imagine the solution. And therein lies the heart of the matter: humans imagine and machines don't.

Eiby's work, with its emphasis on learning and uniquely human skills, reinforces our own theory that our uniquely human ability to create and explore at points of friction is also our uniquely human adaptation advantage. Still, it's difficult for many to stop chasing new skills.

Chasing STEM at Our Peril

Human skills are clearly important, but what about STEM? Society is currently obsessed with STEM skills, valuing science, technology, engineering, and math over humanities and social sciences and rewarding STEM practitioners with higher starting salaries. But when you look beyond entry-level jobs, something interesting happens.

David Deming and Kadeem Noray at Harvard University joined with the employment analytics company Burning Glass Technologies on research that found that “the earnings premium for STEM majors is highest at labor market entry and declines by more than 50% in the first decade of working life.”12 The reasoning for this decline, they say, is that STEM jobs experience the highest rate of technological change, and those in STEM jobs tend, over time, to learn new STEM skills more slowly than new graduates who have dedicated their full-time attention to learning the latest technologies. They also found that 58% of STEM graduates leave the field within a decade.

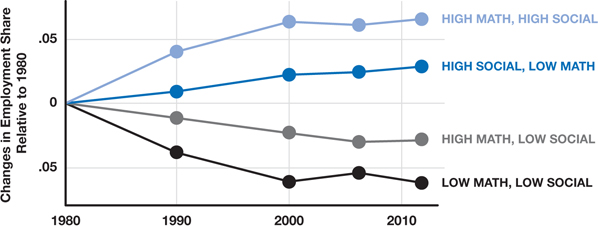

In another, earlier study, Deming looked at STEM-based jobs, specifically those requiring math skills, and coupled them with required social skills. He found that demand to fill jobs requiring high math and high social skills has surged and exceeded the supply of capable applicants. Conversely, demand for talent to fill jobs that require high math but low social skills and jobs requiring neither high math nor high social skills has been on the decline since the 1980s (Figure 8.4). Even more interestingly, jobs that required high social skills but not high math skills have risen in inverse correlation to jobs requiring high math skills but not high social skills. Accompanying the rise and fall of these coupled skills is the relative compensation for those roles (Figure 8.5). “Specifically, today's job market favors those who have the skills to be good team players. Social skills reduce the cost of coordinating with others,” Deming said. “Each time there's a new set of people, they have to figure out anew what their roles are.”

Figure 8.4 Deming: Changes to Employment Based on Task Intensity

Data source: David Deming, Occupational Task Intensity based on 1998 O*NET (source: 1980–2000 Census, 2005–2013 ACS), in “The Growing Importance of Social Skills in the Labor Market,” May 2017.

Figure 8.5 Deming: Changes in Hourly Income Based on Task Intensity

Data source: David Deming, Occupational Task Intensity based on 1998 O*NET (source: 1980–2000 Census, 2005–2013 ACS), in “The Growing Importance of Social Skills in the Labor Market,” May 2017.

Despite the clear advantage of uniquely human skills, we are gutting them from our educational programs globally. Following the 2002 education reform law known as No Child Left Behind, a law hyperfocused on improving math and reading competencies, 22% of surveyed schools reported that they had reduce or eliminated music and arts instruction.13 The 2008 global financial crisis further slashed education budgets, and arts and music programs fell victim to so-called cost savings. Paradoxically, investment in arts and music results in higher levels of both student engagement and persistence.14 Eighteen years after No Child Left Behind became law, these students are entering our workforce en masse.

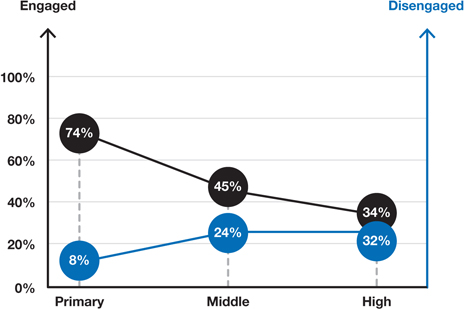

Perhaps worse, a 2016 Gallup survey of 3,000 schoolchildren found 74% of fifth graders reported that they are engaged in learning. That number drops to 45% by grade 8 and plummets to 34% by grade 12.15 Can we really afford to have our kids disengaged from learning when learning itself is the foundational skill for the future? Clearly not, as evidenced by Gallup's State of the American Workplace study that found only 30% of workers are engaged at work, a scenario that costs $450 to $550 billion a year in the United States16 (Figure 8.6).

Figure 8.6 Gallup: Engagement and Disengagement in Education

Data source: Gallup 2016 survey of 3,000 schools in the United States (https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/211631/student-enthusiasm-falls-high-school-graduation-nears.aspx).

This trend in cutting arts and music and hyperfocusing on technology is a global phenomenon. A recent BBC report found that “in China, the government has unveiled plans to turn 42 universities into ‘world class’ institutions of science and technology. In the United Kingdom, government focus on STEM has led to a nearly 20% drop in students taking A-levels in English and a 15% decline in the arts.”17

In the debate of STEM versus uniquely human skills, we spoke with Matt Sigelman, CEO and founder of Burning Glass Technologies. Burning Glass is an analytics software company that provides real-time data on job growth, skills in demand, and labor market trends. Sigelman shared this:

One of the most important trends for jobs in the future is the rise of hybrid jobs. In these roles, you need both technology fluency and human skills to be successful, and perhaps more importantly, to adapt to changes in your work and navigate your career trajectory. I have seen the recent reports that suggest that human skills are now more important and showing more unmet market demand than technology skills. Research from Burning Glass Technologies makes it clear that it is important to have balance: this is not a choice between either technology skills or human skills, but rather a combination of both.

One of the most interesting things we found in our research is that as jobs require more technology skills and knowledge, the intensity of human skills to be successful in the role also increases. That's particularly true for collaboration, research skills, and communication skills. For example, software development roles may be technical jobs, but those jobs are as likely to demand good writing skills as any other job we track. Jobs like these also now require business skills, like project management and data visualization, which are crucial to getting things done and yet haven't traditionally been found in technical roles. What we think may be happening is in our rush and focus on getting everyone to acquire technology skills, we are leaving the human skills behind at a time they are growing in demand.

In other words, a well-intentioned—but ultimately short-sighted—focus on exclusively on STEM will have serious consequences for our future global workforce. In fact, we're already seeing that it does.

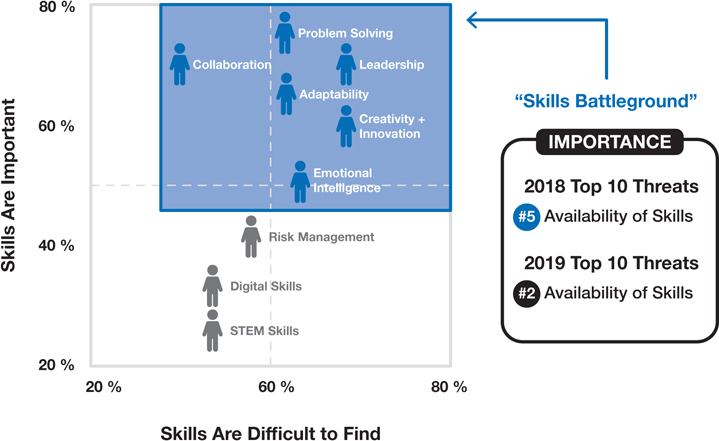

The Skills Battleground: Humans Need Apply

PricewaterhouseCoopers annually surveys CEOs worldwide. In 2019, for their 20th annual survey, the accounting firm polled 1,300 CEOs in over 75 countries to ascertain their greatest priorities looking ahead. This report sums up these concerns in the title alone: “The Talent Challenge: Harnessing the Power of Human Skills in the Machine Age.” The report found that human capital is the number-two concern, with 77% of CEOs reporting that not finding workers with the skills they need is a threat to their business. What is most interesting is that those skills are neither technical nor digital; they are uniquely human (Figure 8.7). Specifically, the skills CEOs found both most important to their business and the most difficult to find were problem solving, leadership, creativity, innovation, and, very notably, adaptability.

Figure 8.7 PricewaterhouseCoopers: Skills Battleground

Data source: PwC 20th Anniversary CEO Survey.

The Return on Being Human

Uniquely human skills will not only be valued in the future, but they are also having an impact today as we straddle the Third and Fourth Industrial Revolutions. As machines strip away routine and predictable work, the complex work that remains requires people who can think across disciplines. No wonder transdisciplinarity is high on ITF's list of valuable future skills. Having an undergraduate degree in one discipline and a graduate degree in another yields higher compensation than a concentration in a single discipline (Figure 8.8). Again, from the BBC report:

In the US, an undergraduate student who took the seemingly most direct route to becoming a lawyer, judge, or magistrate—majoring in a pre-law or legal studies degree—can expect to earn an average of $94,000 a year. But those who majored in philosophy or religious studies make an average of $110,000. Graduates who studied area, ethnic and civilisations studies earn $124,000, US history majors earn $143,000, and those who studied foreign languages earn $148,000, a stunning $54,000 a year above their pre-law counterparts.18

Figure 8.8 The Premium of a Liberal Arts Undergraduate Degree in the Legal Profession

Ironically, many of those undergraduate majors are often dismissed as useless for securing future jobs, even as they provide the key critical thinking and, more importantly, uniquely human skills needed for stable, long-term career success.

Burning Glass has found that if you graduate from a STEM program you get your highest premium in your first starting salary. Over 10 years, unless you infuse your STEM education with other skills, notably uniquely human ones, that premium drops dramatically. Placed in the context of the BBC research, it's reasonable to conclude that technology skills depreciate while human skills appreciate (Figure 8.8).

In their book The Future Computed, Brad Smith and Harry Shum put it this way: “As computers behave more like humans, the social sciences and humanities will become even more important. Languages, art, history, economics, ethics, philosophy, psychology, and human development courses can teach critical, philosophical, and ethics-based skills that will be instrumental in the development and management of AI solutions.” Further, a 2015 study by the British Council that surveyed 1,700 people in 30 countries across a variety of industries found that more than half the people in management and leadership positions had bachelor's degrees in either humanities or social sciences.19 We expect that number to grow even higher in the future as uniquely human skills continue to grow in importance for leadership.

Return on Humans for All Jobs: The Special Power of Empathy

The value of uniquely human skills is evident in jobs of every type, whether or not the job requires a higher education degree. Every job today experiences a return on uniquely human skills, especially those jobs that require extensive human-to-human interaction. Customer service. Personal care. Hospitality. Sales. The entire service industry, from restaurants to retail. This includes every job that involves interaction with other humans, which we would argue is almost 100% of work. In these high-touch jobs, the most powerful and underestimated uniquely human skill is empathy. Or, to use Donna Patricia Eiby's language, empathy is the key to removing friction.

In 2009, Dev Patnaik, founder and CEO of the innovation consulting firm Jump Associates, wrote the book Wired to Care: How Companies Prosper When They Create Widespread Empathy. In it, he details Jump's experiences using empathy to unlock creativity and innovation. Describing itself as a total systems thinking management consulting firm, Jump leverages empathy to create products and services better aligned with customers’ real needs and desires. “The best organizations and the ones that survive economic tsunamis,” Patnaik says, “are those with empathic cultures and managers who are able to step outside themselves and walk in someone else's shoes.”

The power of empathy isn't limited to the creation of commercial goods, however. It is the heart and soul of healthcare, education, and governmental reform. For example, an Italian study of more than 20,000 patients with diabetes looked at the power of empathy in wellness. Patients were divided among three groups of physicians. All physicians were prescreened for their levels of empathy. The patients treated by the physicians with higher levels of empathy had statistically significant lower levels of diabetic complications than those served by the physicians with lower levels of empathy.20

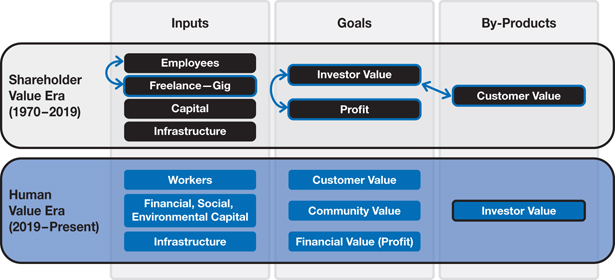

Evolving Beyond Shareholder Value: The Purpose of a Company

On September 13, 1970, in an article in the New York Times titled “The Social Responsibility of a Company Is to Increase Profits,” economist Milton Friedman argued that the sole purpose of a company was to generate returns for shareholders.21 For nearly 50 years now, companies have done precisely that. According to the Economic Policy Institute, from 1979 to 2018, productivity grew almost 70% while wages increased less than 12%.22 Friedman's declaration launched the shareholder value era. Companies merged, downsized, right-sized. They reduced the size of their workforces and treated our natural resources as unending. They prioritized shareholder value over employee value, and often even over customer value. Once a by-product of overall value creation, shareholder value became the guiding principle for companies. Where human workers were once considered an asset to develop, they instead became a cost to contain. The Business Roundtable, a collection of America's most influential CEOs and leaders, shared that corporate shareholder priority from 1997 to 2019.

Until something changed.

In 2019, the Business Roundtable released its “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation,”23 signed by nearly 200 CEOs, which reads, in part, as follows:

Americans deserve an economy that allows each person to succeed through hard work and creativity and to lead a life of meaning and dignity. We believe the free-market system is the best means of generating good jobs, a strong and sustainable economy, innovation, a healthy environment, and economic opportunity for all.

Businesses play a vital role in the economy by creating jobs, fostering innovation, and providing essential goods and services. Businesses make and sell consumer products; manufacture equipment and vehicles; support the national defense; grow and produce food; provide health care; generate and deliver energy; and offer financial, communications, and other services that underpin economic growth.

While each of our individual companies serves its own corporate purpose, we share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders. We commit to:

- Delivering value to our customers. We will further the tradition of American companies leading the way in meeting or exceeding customer expectations.

- Investing in our employees. This starts with compensating them fairly and providing important benefits. It also includes supporting them through training and education that help develop new skills for a rapidly changing world. We foster diversity and inclusion, dignity and respect.

- Dealing fairly and ethically with our suppliers. We are dedicated to serving as good partners to the other companies, large and small, that help us meet our missions.

- Supporting the communities in which we work. We respect the people in our communities and protect the environment by embracing sustainable practices across our businesses.

- Generating long-term value for shareholders, who provide the capital that allows companies to invest, grow and innovate. We are committed to transparency and effective engagement with shareholders.

Each of our stakeholders is essential. We commit to deliver value to all of them, for the future success of our companies, our communities and our country.

Reflecting on this profound shift, Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever from 2009 to 2019, said in a New York Times interview, “You cannot solve issues like poverty or climate change or food security with the myopic focus on quarterly reporting. We have to move the financial markets to the long term as systems change. We need to decarbonize this global economy if we want to keep it livable. We need to find an economic system that is more inclusive.”24

This sea change in corporate culture, at least in language, comes at a critical time as human and technology assets vie for their place in the corporate value chain. By acknowledging the value of human workers as an essential link in that chain, these CEOs are, in effect, embracing the power of the adaptation advantage and the potential of uniquely human skills, giving those skills and the humans who possess them renewed stature in the corporation (Figure 8.9).

Figure 8.9 Shareholder Value and Human Value Eras

To Maximize Human Potential, Place the Human in the Center

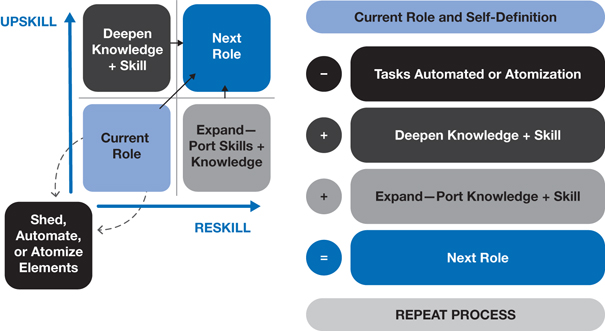

We've said it many times in many ways: technological capability is growing at an incomprehensible rate. We will soon experience automation and niche artificial intelligence, or, as we prefer to call it, silicon cognition, as reliable collaborative tools. What we can't say often enough, though, is this: every time we hand something off to a technology actor—whether to automation or niche silicon cognition—we must reach up and learn new skills that enhance and evolve our own capabilities. It is this awareness and ability to reach and learn that lies at the heart of the adaptation advantage.

Terms like upskilling and reskilling are used without explanation, so let's give them a definition. Reskilling is acquiring new skills to expand your abilities to new industries or contexts; by reskilling, you are often replacing one set of skills or applications with another. Upskilling is deepening your knowledge or abilities in the domains where you currently operate. To navigate the evolution of work, we will need to do both. But rather than continuously grasping for the newest technology, focus on nurturing your uniquely human skills alongside your technical literacy. That will enable you to reach greater levels of human potential. Your job is moving, and if you are not moving with it, it may be moving away from you (Figure 8.10).

Figure 8.10 Your Job Is Moving: Reskill and Upskill Every Day

We have only begun this journey. In 2015, the McKinsey Global Institute estimated that only 18% of the US economy had been digitized.25 Of those digital transformations, McKinsey claims, less than 30% are successful. Given these numbers, it's clear that most of the digital transformation is yet to come. This digital transformation is the necessary first step toward leveraging silicon cognition, automation, and augmentation, and so it is now that we must be mindful to place humans at the center of that transformation. Have no doubt about it: when we use phrases like “digital transformation,” we are really talking about “human transformation.”

While no one is insulated from the changes ahead, McKinsey reports that “Routine predictable physical and cognitive tasks will be the most vulnerable to automation in the coming years.”26 In some areas of our economy, early phases have already occurred. A recent study by Ball State, “The Myth and the Reality of Manufacturing in America,” found that the majority of the 5 million manufacturing jobs lost since 2000 were outsourced to history and replaced by technology.27 We had no plans for either upskilling or reskilling those 5 million Americans, so we lost them as a valuable resource to the industries to which they were contributing. This is a profound loss of human potential to our economy and our society.

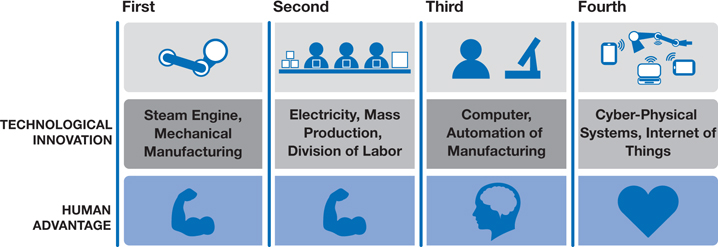

Looking ahead, it will be our least educated workers, especially those in routine or predictable work, who will be most vulnerable to automation. Indeed, they already have been. We must proactively plan for a productive and engaged workforce by placing the human at the center of our transformation plans (Figure 8.11). As Dame Minouche Shafik, director of the London School of Economics and Political Science, noted in a recent interview, “In the past jobs were about muscles, now they're about brains, but in future they'll be about the heart. We need to invest to make sure that both young people and current workers have access to the kind of training they'll need to adjust to this new labor market. That is what we should be thinking about.”28

Figure 8.11 The Fourth Industrial Revolution Requires Heart

Concept credit: Dame Minouche Shafik, director, London School of Economics and Political Science, and Dov Seidman, CEO, LRN and author of How.

Rise of the humans indeed.

Notes

- 1 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/09/technology/facial-recognition-race-artificial-intelligence.html

- 2 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3049090

- 3 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/28/technology/paul-allen-ai-common-sense.html

- 4 https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2018-10-11

- 5 https://news.microsoft.com/2019/07/22/openai-forms-exclusive-computing-partnership-with-microsoft-to-build-new-azure-ai-supercomputing-technologies/

- 6 https://www.wired.com/story/power-limits-artificial-intelligence/

- 7 http://bigdata-madesimple.com/exciting-facts-and-findings-about-big-data/

- 8 https://www.cisco.com/c/dam/en_us/about/ac79/docs/innov/IoT_IBSG_0411FINAL.pdf

- 9 https://www.networkworld.com/article/3325397/idc-expect-175-zettabytes-of-data-worldwide-by-2025.html

- 10 https://go.forrester.com/blogs/hadoop-is-datas-darling-for-a-reason/

- 11 https://hbr.org/2016/01/collaborative-overload

- 12 https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/ddeming/files/demingnoray_stem_sept2018.pdf

- 13 https://thehill.com/opinion/op-ed/7275-no-child-left-behind-act-wrongly-left-the-arts-behind

- 14 https://www.lawstreetmedia.com/issues/education/cutting-art-programs-schools-solution-part-problem/

- 15 https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/211631/student-enthusiasm-falls-high-school-graduation-nears.aspx

- 16 https://news.gallup.com/businessjournal/162953/tackle-employees-stagnating-engagement.aspx

- 17 https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20190401-why-worthless-humanities-degrees-may-set-you-up-for-life

- 18 https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20190401-why-worthless-humanities-degrees-may-set-you-up-for-life

- 19 https://www.britishcouncil.org/voices-magazine/what-do-worlds-most-successful-people-study

- 20 https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2012/09000/The_Relationship_Between_Physician_Empathy_and.27.aspx

- 21 http://umich.edu/∼thecore/doc/Friedman.pdf

- 22 https://www.epi.org/productivity-pay-gap/

- 23 https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans

- 24 https://www-nytimes-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.nytimes.com/2019/08/29/business/paul-polman-unilever-corner-office.amp.html

- 25 https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/high-tech/our-insights/digital-america-a-tale-of-the-haves-and-have-mores

- 26 https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/unlocking-success-in-digital-transformations

- 27 https://conexus.cberdata.org/files/MfgReality.pdf

- 28 http://www.alainelkanninterviews.com/minouche-shafik/?fbclid=IwAR3HF3bB