4

Ed Pincus and the Emergence of Personal Documentary

The social turmoil of the late 1960s and early 1970s brought with it a wholesale reevaluation of many of the institutions that had seemed to define American culture for the previous generation. The federal government had involved the nation in a war during which the American military perpetrated shocking, inhumane brutalities against a humble underdog—to many young people coming of age, America seemed the new Third Reich. State governments that had condoned generations of American apartheid came under attack from their own disenfranchised citizens and from “outside agitators,” including a president and attorney general educated at Harvard. Under pressure from students and faculty, colleges and universities were beginning to rethink their economic and ethnic exclusivity. And a new wave of feminism was questioning the nature of male–female relationships, the institution of marriage, and one of the central assumptions of the American nuclear family: a belief in privacy. Indeed, the broad green lawns that surrounded the new suburban homes springing up during the post–World War II years were a visual emblem of the idea of privacy; they kept auditory evidence of family problems away from the ears of potentially prying neighbors.

Within this volatile social climate, it is hardly surprising that for a new generation filmmaking became a means for investigating problematic traditions and promoting cultural change. Newsreel and other filmmaking collectives made it their business to confront mainstream depictions of international events and national policy. Many avant-garde filmmakers confronted the fundamental assumptions of moviegoing and television watching, inventing new formal strategies that redefined the nature of spectatorship. And in Cambridge and other locations, documentary filmmakers began to carry 16mm cameras and video camcorders into the inner sancta of family and personal relationships in order to see what might be learned about the ways in which the unfolding of daily experience reflected problematic ideas and social patterns.

In Cambridge this new interest took two different forms. In some instances, filmmakers directly confronted family members, recorded the results of these confrontations, and shaped these records into new understandings of family life and their own positions within it. In other instances, filmmakers reexamined the previous generation’s records of family interaction—stories frequently retold within the family, home movies, family photographs—to see what these records might tell us about the ways in which the traditional family had functioned and how changes in technology and social organization were affecting what had seemed essential to an earlier generation and its concept of family.

THE MIRIAM WEINSTEIN QUARTET AND RICHARD P. ROGERS’S ELEPHANTS: FRAGMENTS OF AN ARGUMENT

Some filmmakers in this new generation, directly or indirectly influenced by the women’s movement which began to find significance in what was called the personal, began to avoid famous personalities, newsworthy events, and the obviously lofty subjects. . . . Everydayness for the first time became a possible subject. Ordinary people in ordinary situations, no longer defined by a social role that was their entrée to being the subject of a film—race car driver, actress, prisoner, poor person, politico. Their justification for being a film subject was often only that they had a relationship with the filmmaker or were somehow accessible to the filmmaker. Like any possibility, this one has been abused and there have been a rash of sentimental personal films. But in the most interesting, people divorced from their social definitions became interesting in new ways.

ED PINCUS

Also, previous to the women’s movement, there was a branch of SDS, the Weathermen, whose slogan was “The pig is in us.” We were supposed to look inside.

IDEM1

In the general introduction to this study, I suggest that ethnographic film and what came to be called personal documentary are the inverse of each other. This seems obvious to me in the same way that it seems obvious that during the dawn of documentary filmmaking, the two major forms—what Erik Barnouw called “films of exploration” (Nanook of the North, Grass, Moana) and the City Symphony: that is, films about the industrial centers of modern nations (Berlin: Symphony of a Big City, The Man with a Movie Camera)—were the inverse of each other: the explorations of far-flung locations and peoples in Flaherty’s and Cooper-Schoedsack’s films were tied to the industrial center of modern life by a celluloid umbilical cord. In Cambridge, however, this connection was more than theoretical conjecture; it was (and remains) a fact of everyday experience. Alfred Guzzetti, who would complete his landmark personal documentary, Family Portrait Sittings, in 1975, was a student in the first class in filmmaking Robert Gardner taught in the Carpenter Center and remembers admiring Gardner tremendously: “I was in awe of Dead Birds and then Rivers of Sand.”2 Guzzetti thought of these films as very “Other,” but his own rebellion in Family Portrait Sittings against cinema verite filmmaking’s tendency to base films on short-term explorations of high-profile events in favor of a more in-depth look at quotidian family life may owe something to the in-depth explorations of everyday experience that produced Gardner’s first ethnographic features. Another instance: between the time Ross McElwee began shooting the footage that would find its way into Backyard, his first personal documentary, and the completion of that film in 1984, he accompanied John Marshall to the Kalahari Desert to assist in the shooting of what became N!ai, the Story of a !Kung Woman (1978).

While the emergence of personal documentary was an important new development in the 1970s, it was preceded both by a considerable body of personal cinema produced by American avant-garde filmmakers and by what remains the most interesting satire of personal documentary. Among the most important figures in this earlier exploration of the personal are Stan Brakhage, Jonas Mekas, Carolee Schneemann, and Andrew Noren. Much of Brakhage’s early filmmaking was centered on his family life with Jane Brakhage and their children. The “personal” for Brakhage, and for these other filmmakers, however, meant more than a focus on the activities of self, family, and friends; the filmmakers’ personal events and activities were recorded by handheld, often gestural camerawork, and presented within idiosyncratic editing strategies that were intended to express the filmmakers’ psychic experiences and aesthetic interpretations of the events and activities depicted. In Window Water Baby Moving (1959), for example, we are not simply watching Jane Brakhage give birth to a daughter; we are watching Stan Brakhage’s immediate reaction to the birth process—we can feel his excitement, his anxiety, the ways in which the process of birth triggers particular memories—and his subsequent interpretation of what the experience meant to him in an expressive montage.

Much the same can be said of Carolee Schneemann’s Fuses (1967), the filmmaker’s record and interpretation of her lovemaking with composer James Tenney; of Walden (1969), Mekas’s “home movie” of the emergence of the New American Cinema in New York during the 1960s; and of Huge Pupils (part 1 of The Adventures of the Exquisite Corpse; 1968), Noren’s record of light and love. In all these films, gestural camera movement and new approaches to editing create visceral forms of personal expression roughly analogous to the kinds of personal expressiveness characteristic of abstract expressionist painting. An exploration of the various forms of the “personal” in personal cinema is a challenge for a different book, but roughly speaking, the distinction between this earlier, “avant-garde” sense of the personal and what I am calling “personal documentary” has to do with the use of sound and in particular, of conversation, usually recorded in sync.

The widespread popularity of personally expressive cinema during the 1960s was depicted and satirized by Jim McBride in his David Holzman’s Diary (1967), though in one of the strange ironies of film history, McBride’s satire was largely irrelevant in relation to the personal cinema I’ve just described—except for the fact that Andrew Noren was the inspiration for David Holzman.3 It was, however, remarkably prescient. McBride and L.M. Kit Carson, who played David Holzman in McBride’s film, had interviewed some of the major proponents of cinema verite (“Ricky Leacock, Pennebaker, Bob Drew, the whole bunch”) for a monograph sponsored by the Museum of Modern Art.4 The monograph was never completed, but their research was incorporated into David Holzman’s Diary, in which McBride conflated his interest in the immediacy of the on-the-spot sync-sound filmmaking that had emerged during the early 1960s (along with the claims of those who celebrated cinema verite’s supposed access to unmediated reality) with the personal revelations of the avant-garde filmmakers who were so visible in New York (McBride and Carson had also interviewed Andy Warhol, Gerard Malanga, and Noren). Though David Holzman’s Diary is a fiction, and a trick film (even contemporary audiences are shocked when the credits roll), as Jim Lane has said, McBride’s film seems, in retrospect, at least a premonition, and perhaps an instigation, for the rise in personal documentary in Cambridge beginning in the decade that followed.5

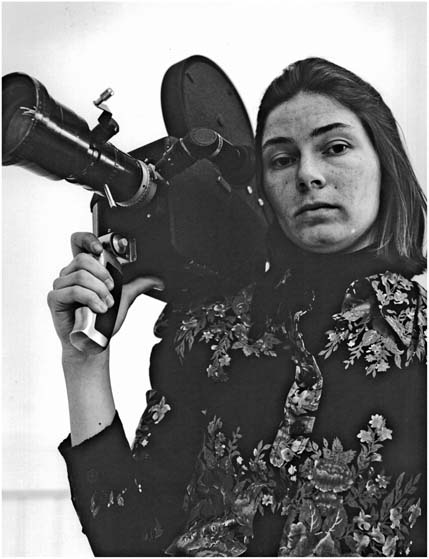

While David Holzman doesn’t resemble Andrew Noren in the slightest (nor could David Holzman’s Diary ever be mistaken for a Noren film), McBride’s feature is remarkably close to films that Miriam Weinstein, Richard P. Rogers, Ed Pincus, Ross McElwee, Ann Schaetzel, and others would come to make during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Further, as Ed Pincus has suggested, the emergence of the form of personal documentary McBride imagined in David Holzman’s Diary had much to do with the impact of the wave of feminism that was developing at the same time. For the first generation of avowedly feminist filmmakers, both women and men, the idea that in gender relations “the personal is the political” was particularly relevant to filmmaking. Of course, Hollywood, much of the European art cinema so popular during the 1960s, and even a good many avant-garde filmmakers had portrayed women in very limited ways, undervaluing women’s labor and fantasizing about women’s bodies. A new generation of independent women filmmakers, and particularly documentary filmmakers, envisioned and created a counter-cinema that exposed the realities of women’s lives in middle-class American culture. Among the earliest of these feminist filmmakers, and perhaps the most prescient of the developments in personal documentary that would soon occur, was Miriam Weinstein (fig. 18).

FIGURE 18. Miriam Weinstein in the 1970s. Courtesy Miriam Weinstein.

Between 1972 and 1976, Weinstein completed a quartet of films about her own life—My Father the Doctor (1972), Living with Peter (1973), We Get Married Twice (1973), and Call Me Mama (1976)—that offered a panorama of crucial developments in the life of a young, middle-class woman and of Weinstein’s exploration of the options available for the personal documentary filmmaker.6 Ed Pincus was an important model for Weinstein’s filmmaking: “Ed was the elder statesman of the Cambridge scene (he is probably only a few years older than I am). . . . In 1968, which was a time of tremendous social upheaval, the young media types would meet at Ed’s house/office. There was a lot of discussion about how we would cover events that were happening, disseminate information, etc. etc. I remember covering actions by VVAW (Vietnam Veterans Against the War) and similar groups.”7 Pincus’s Diaries (1971–1978), which has much in common with Weinstein’s films, would not be finished until two years after her final personal documentary, but Pincus often presented early rushes, and Weinstein believes she probably saw some of these.8

In My Father the Doctor Weinstein’s interview with her father is embedded within still photographs and home movies of her grandparents, parents, and of herself and her sister as children. The interview focuses on Saul Weinstein’s pride in his daughter’s education (she graduated from Brandeis with honors in painting) and on Miriam Weinstein’s interest in how her father became a doctor and how he feels about her being a filmmaker: “Are you surprised?,” she asks him. His disappointment is evident; he had imagined that Miriam would find her way into a profession more appropriate to her being a “brain.” In Living with Peter the focus is Weinstein’s anxiety about living with Peter Feinstein without being married, an anxiety evidently not shared by her mother (“I think it’s great, because I’ve done it, long before you did”) or Peter’s sister. Throughout the film, Weinstein talks with Feinstein about the possibility of their getting married—he doesn’t want marriage, she does—and with a pair of friends (Deac Rossell, who ran the film program at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, at the time, and his wife, Mickie Meyers) who got married without living together first and are enthusiastic about their choice.

We Get Married Twice documents Weinstein and Feinstein’s two weddings, one of them held informally at their home, the ceremony conducted by a Methodist minister friend; the other, a more formal wedding in a synagogue, overseen by a rabbi, and instigated by Weinstein’s mother and acceded to by Feinstein, once it was made clear to him that a formal wedding would be economically rewarding: “So being a pragmatist, we decided it would be fun to get married in true style in New York City by the same rabbi who married Saul and Sally Weinstein.” Call Me Mama focuses on the typical activities of Weinstein’s young motherhood: she and her two-year-old son, Eli, are seen at home, in a park, visiting a friend and her young daughter, and reading, as Weinstein in voice-off describes the pleasures and struggles of being a mother. The struggles seem to have included Feinstein’s early lack of interest in his young son: “I was having a difficult time being a mother and trying to make sense of my life. Although the women’s movement had made it okay for women to work, etc. etc., I did not really believe it. And Peter had very little interest in being around little children, so it was not a happy period, although both my kids were great kids and I loved being with them. But still, I look at that movie and I see claustrophobia.”9

Each of the four films uses a different filmmaking strategy. In My Father the Doctor Weinstein intercuts between recycled photographs and home movies of her family and her interviews with her father: she is never visible, but we hear her behind the camera asking questions; indeed, her presence as filmmaker/interviewer and his responses as subject/interviewee provide the drama of the film.10 In Living with Peter Weinstein is also the interviewer behind the camera, though in this case, the fact of her filming, at least in the case of her conversations with Feinstein, is more directly an issue: Feinstein is clearly annoyed (or pretends to be annoyed) by the filming, and when Weinstein asks him, “Do you feel any pressures to do it [get married]?,” Feinstein responds, “Well, I didn’t until you started making this movie!”11 Later, when they are talking about their visits to family over Thanksgiving, she tells Peter, “This film is about you and me and about marriage. Could you please say something about Thanksgiving that’s more relevant?” Near the end of the film, Weinstein jumps through time, and in a later conversation with Feinstein, it becomes clear that he has given her a wedding ring for her birthday. Weinstein’s interviews with Feinstein are more intimate than those with her father in My Father the Doctor or with the other subjects in Living with Peter; especially during their conversation in the bathroom as Feinstein is shaving, their conversation is a kind of intimate banter reflected by Weinstein’s filming in extreme close-up.

In addition to interviewing Feinstein and the others, Weinstein sits on the bed in their bedroom and addresses the camera in several monologues, first talking about how her unmarried status has caused her to be rejected by an insurance company “for moral reasons” and admitting, “I just wanted to kind of use it [this rejection] as an excuse to get married. . . .” In a second monologue, she reveals that none of the people she’s interviewed seem bothered that she is living with Peter: “The whole thing has been a little bit anticlimactic.” A final monologue, after Peter has given her the ring, reveals that the idea of marriage has become “less important” to her, though she continues to want marriage more than Peter, “and in a way that’s why I’m making the movie too. Because I want to talk about it and I want it to be something I can talk about.” She has a ring but is not a wife, and “girlfriend is getting a bit ludicrous at this point.” Weinstein’s monologues in Living with Peter are, of course, evocative of David Holzman’s monologues in David Holzman’s Diary and a premonition of the monologues in several of Ross McElwee’s films—though hers seem a good bit more unrehearsed than McElwee’s. Indeed, the intimacy and immediacy of Weinstein’s films is generally reflected in, and communicated by, a variety of glitches: the sound of the camera, a visible microphone here and there, sudden changes in sound level and light values.

For We Get Married Twice, which was made with the assistance of the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard, Weinstein asked others to document her two weddings: Len Gittleman did camera and sound for the informal wedding at home, and the formal Jewish wedding was recorded by Henry Felt (camera), Marilyn Clayton (sound), and Ed Joyce (lighting). The differences in the weddings are reflected by the differences in the two documentations. The more intimate first wedding is presented in a free-form style, evocative of Brakhage and Mekas. No sync sound is used; at the beginning Weinstein and Feinstein introduce this wedding in voice-over; subsequently we hear the comments of the participants and guests (along with the sound of the camera running), and near the end of this section of the film Weinstein talks about the after-party and the days that followed. We see bits of the events in stills and in handheld motion pictures, often in passages of slow motion and stop action, and very largely in close-up.

The depiction of the first wedding lasts a bit more than 7 minutes; the formal wedding, about twice as long, is presented in a more traditional documentary manner. Nearly the entire event is presented in sync sound and focuses on interviews with various participants and guests who are identified by superimposed titles (“my sister,” “my sister’s boyfriend,” “my father”). Weinstein is told by her mother that filming will not be allowed in the synagogue during the ceremony because of the lights and the distraction (Feinstein asks Sally Weinstein, “God doesn’t like extra light?,” triggering some barely repressed anger). Despite this restriction, the ceremony is represented in the finished film—as an audio recording; the screen remains dark during this passage (a premonition of a remarkable moment in McElwee’s Time Indefinite; see p. 217). While the second wedding may have placated her parents, Weinstein herself seems less than enthusiastic about it (“I didn’t like the rabbi”), while Feinstein seems to have found it exhilarating.

Call Me Mama was also recorded by others—John Terry (photography) and Pat Lockhart (sound recording)—but directed and edited by Weinstein. Recognizing that she could not mind Eli and make a film (Feinstein is entirely absent from Call Me Mama), “I decided somebody else had to be behind the camera and I would have to be in the film with Eli.” Call Me Mama is recorded sync sound, and Weinstein provides an ongoing voice-off narration about her struggles to be a good mother and to continue to do her own work. The result is reminiscent of Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen’s Riddles of the Sphinx, which was finished the same year.

Weinstein’s quartet of films may now seem typical of the feminist filmmaking of the 1970s, but her exploration of the possibilities of her own presence in documentations of her own experiences is an early breakthrough that would be developed by many other filmmakers. Further, however personal these films seemed during the 1970s, they seem a good bit more than personal now. Earlier chapters of this book have suggested that in the films of the Marshalls, Robert Gardner, and Timothy Asch, the quest to objectively document long-surviving cultures under the threat of transformation by the relentless spread of modern life led first to idealized fantasies, then to careers in which the personal lives, beliefs, and the filmmaking and teaching activities of the filmmakers themselves became increasingly central. The inverse has tended to be true in the history of personal documentary. What began as a variety of attempts to depict and analyze the filmmakers’ most personal feelings and activities has increasingly become ethnographic evidence about life in the United States, including the changing role of filmmaking within family life.

This is certainly evident in Weinstein’s films. As is clear in films that have recycled home movies—Alan Berliner’s The Family Album (1986), the Austrian Gustav Deutsch’s ADRIA, Film—Schule des Sehens 1 (1990), much of the work of Peter Forgács—the home movie was for many decades largely a record of certain forms of performance for the camera. The advent of sync sound didn’t entirely change this, of course, but it added the option of interviewing, and as a result, amateur home movie makers and personal documentary filmmakers alike could not only record their family members’ antics in front of the camera but could elicit responses to questions asked within the immediacy of family interaction. In Weinstein’s My Father the Doctor it is obvious that Weinstein’s position as filmmaker has given her the reason and the courage to ask her father about his feelings and is the motivation for Saul Weinstein’s considered and sometimes revealing answers: when Saul reveals his earlier hope that Miriam might go into the sciences or mathematics, Miriam responds that girls weren’t expected to understand about science and math. Saul’s startled “Why?” suggests how assumptions about women were changing; Saul has given up a stereotype, even if Miriam continues to be affected by it. Further, his attempt to take his daughter’s filmmaking seriously confirms his considerable respect for her intelligence.

The debate about living together versus marriage in Living with Peter may seem quaint to a post–sexual revolution audience, but Weinstein’s film does document, from within an unfolding relationship, an issue that affected many middle-class American young people and their families during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Living with Peter reveals not just the issue itself, but the ways in which young people and their parents articulated their ideas about this issue. During the years when Weinstein was making her personal documentaries, she was in touch with Jane Pincus, who was one of the founders of Boston’s Our Bodies, Ourselves collective: Weinstein remembers, “We began to think that maybe personal concerns deserved some attention—a very new idea for women.”12 Weinstein’s candidness about her own deviousness in pushing for marriage reveals how women (and men) could identify themselves as feminists while continuing to see themselves in problematic ways and allowing themselves to be patronized by men even within their personal relationships. Weinstein’s four films reveal a woman in the throes of personal transformation: on one hand, she is acceding to the conventional by pushing for marriage and later, by taking full charge of her young son; on the other, she is demonstrably a working filmmaker—and she was among the first to carry her camera and tape recorder into her family life to document the ways in which societal changes were affecting intimate relationships in American middle-class lives.13

At the beginning of Elephants: Fragments in an Argument (1973; the opening title divides elephants into its three syllables: el·e·phants), and following the credits (which are accompanied by the sound of his father apparently looking at and identifying family photographs), Richard P. Rogers presents a montage of close-up shots of elephants in a zoo: we see skin, a tail, an ear, an eye, the face seen through the bars of a cage, a foot with a chain around it, the top of the head, the back, the trunk, an ear, and skin again. During this montage we hear, first, Rogers’s father, B. Pendleton Rogers, saying that his son, “like anybody else, has to sit down, and do some—as you are—weighing the different possibilities. You do have to take some chances; you do have to have some faith; you do have to be a little brave,” followed by his mother Muriel Gordon Rogers’s first comments (these begin as we see the chained elephant’s foot): “I do think that possibly Kathy Rogers, Kathy Dodge had guts.” My assumption is that Rogers means to evoke the well-known story about the blind men and the elephant: asked to touch an elephant and decide what it is, the man who touches the leg decides the elephant is a pillar; the man who touches the tail, believes it’s rope, and so on. In its various guises in several cultures the story has usually been thought to illustrate that a single point of view cannot reveal the truth.

The relevance of this story to Elephants is multifaceted. Rogers seems to be making the film to try and come to terms with the various forces shaping his life as a young man: near the end of the film, intercut with a second montage of the elephants, we see him cleaning his small apartment as he delivers a brief monologue that begins, “I’m twenty-nine years old; I live at 20 Trowbridge Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, in this apartment; I teach at Harvard University where I went as an undergraduate and where I went as a graduate student.14 I wanted to make a movie about anger or about limits and about the forces that limited someone, but they had no control over, like their family and their past and their relationship to power in the society that they lived in.” While Elephants draws no clear conclusions, the body of the film does explore the forces that seem to be affecting Rogers.

In Elephants family is represented in two ways—the same two ways Weinstein uses in My Father the Doctor: through family photographs from the past and through conversations with family members (in this instance, Rogers’s father and mother). The family photographs and Rogers’s parents’ comments make clear that both families were rich and powerful, but that for whatever reasons, much of their power and money has vanished—though both parents, now divorced, seem to live quite luxuriously: the father in Manhattan, the mother in the Hamptons. Early in Elephants, as Rogers’s mother talks about the family’s past (sometimes we also hear the father’s voice superimposed with hers), Rogers presents a black-and-white photo montage (one image dissolving into the next) that makes clear how luxurious the lifestyle of his recent ancestors was. While B. Pendleton Rogers seems worried about his son’s lifestyle and is dubious that Rogers’s filmmaking will yield him a decent living, Rogers’s mother is downright hostile: she seems entirely self-involved, desirous of being left alone: “I don’t like your tripod and your cameras and all your instruments all over my living room; it is my right to tell you to get them the hell out!” For the young filmmaker, family seems largely repellent; indeed, he seems to have foresworn any financial support from them.

The review of family history via photographs ends with a shot of Rogers as a baby, followed by a live action color shot of Rogers as an adult (his face, in close-up, moves across the frame from right to left). As we hear Rogers reading a passage from Karl Marx (“It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness”), the film transitions from imagery of Rogers’s family’s past and present, first into a color sequence of close-up images of his cramped and grungy apartment and then into a long sequence of black-and-white imagery photographed on city streets, often in slow motion: kids having their pictures taken by apparently loving parents; porn theaters (Rogers films imagery inside one of the theaters), prostitutes, indigent street people, young women chosen for their erotic appeal. It is clear that Rogers is more at home, at least as a filmmaker, in these lower-class settings than with his angry mother or his vague father.

During the on-the-street sequence, imagery of one young woman (Terry Villafrade) becomes increasingly prominent and leads into the final major focus of the film: Rogers’s relationship with her. We see black-and-white film imagery of Villafrade, shot apparently at various moments over a period of four years, contextualized by a sync-sound interview, during which she describes meeting Rogers when she was seventeen (she was in Cambridge alone, with no place to stay, and approached him), and their various, sometimes erotic, interactions over the years (Villafrade is naked in several shots). While this seems an affectionate, if rather haphazard relationship, it is clear, at least to Villafrade, that both she and Rogers interacted out of loneliness and that this relationship has no future. This sequence is interrupted by a long, color shot of Harvard Yard set up for graduation and leads into the closing sequence of Rogers cleaning the apartment and describing what he had hoped to accomplish by making Elephants. The film concludes with Rogers’s voice-over, “I don’t have any way to end this,” and as we see end-of-roll perforations, “Why don’t you just let it run out?,” followed by a brief interchange with his father, who says, “Nothing ventured, nothing lost,” and is corrected by Rogers: “It’s nothing ventured, nothing gained.”

While Elephants has much in common with Weinstein’s earliest films, Rogers’s first foray into personal documentary is in some senses quite distinct from My Father the Doctor, Living with Peter, and We Get Married Twice. Weinstein’s films document small but real successes in her life, as a daughter, partner, and wife, as well as in filmmaking. Elephants, while technically more adventurous and accomplished than Weinstein’s films, is a record of a period of confusion and frustration; the film provides no conclusion and no indication that filmmaking has been useful to Rogers personally, except in the sense that it has given a lonely young man a way of interacting with his family’s past and the world around him. Elephants feels ragged and a bit out of control—an effective expression of a life in crisis.

Rogers would return to personal documentary ten years later, with 226-1690 (1984)—the title refers to his phone number in New York City. Using only messages left on the answering machine he shared with photographer Susan Meiselas, from New Year’s Day 1984 to Christmas of that year, accompanied by imagery shot (by both Rogers and Meiselas) out the windows of their apartment in lower Manhattan, Rogers fashions a fascinating, engaging revelation of the complex life he and Meiselas were living during that year, a life full of work, lovers, the demands of friends and family (we recognize the voices of B. Pendleton Rogers and Muriel Gordon Rogers, neither of whom seems to have changed during the years since they were recorded for Elephants), within ongoing political developments.

1973 was a pivotal year in the emergence of the forms of personal documentary that were to become characteristic of Cambridge; and Weinstein and Rogers invoke the two approaches to the cinematic exploration of family that would characterize the feature films that would become the major achievements of Cambridge-based personal documentary: the use of filmmaking as a means of engaging family life as it is evolving around the camera and the exploration of familial past using visual documents of this past and oral history. While these two approaches are combined in Weinstein’s films and in Elephants, Ed Pincus, Alfred Guzzetti, and Ross McElwee would develop forms of personal documentary that would be characterized by an emphasis on one or the other of the two approaches.

ED PINCUS’S DIARIES (1971–1976)

There is a strange existential experience of seeing oneself on film, seeing oneself as others see you. . . . What a humiliating and humbling experience to appear equally as others appeared before. What is the nature of all our lives and our relations with others, our little lies and pretenses? . . . A new kind of filmmaker has emerged who deals with these questions. They find their material directly around them. They relate to the old traditions of American cinema verité by having a deep respect for the world as it exists independently of the presence of the camera, and although they often participate in different ways in the film, they do not in general manipulate action for the camera. . . .

ED PINCUS15

Ed Pincus’s career as a filmmaker and filmmaking teacher has been productive, influential, and very unusual. For several of his most productive years he was stalked by Dennis Sweeney, who had threatened his life and the lives of his family and who did kill civil rights attorney and liberal Democratic politician Allard Lowenstein in 1980.16 Because of this, and because of his personal inclinations, Pincus turned away from filmmaking and remained largely out of the public eye for decades: since 1987 he and Jane Pincus have managed a flower farm in Vermont. Pincus’s reemergence in 2007 as co-maker with Lucia Small of The Axe in the Attic, a documentary of the Hurricane Katrina disaster and the experience of trying to document it (see chapter 7), made clear that Pincus remained capable of making contributions to modern independent cinema.

Pincus began his career as a filmmaker in Cambridge not long after studying photography at the Carpenter Center at Harvard and telling Robert Gardner that he had absolutely no interest in filmmaking. When two friends, Sweeney and D.J. Smith, who knew Pincus had made a couple of short films, asked him if he’d be willing to go to Mississippi and document the freedom schools that had been established by civil rights activists, he agreed—“I had wanted to go down south and do something in the civil rights movement”—and proceeded first to enlist David Neuman (a Harvard dropout-turned-craftsman friend who would collaborate with Pincus on several films) to do sound; and then, to rent a camera from John Marshall: “I asked John for some instruction [on how to use the camera], and he said, ‘Put it on your shoulder and push the button; you’ll do fine.’ That was all the instruction I had. David had about the same amount of instruction for taking sound. We had to figure things out from scratch.”17 In the end Black Natchez (1967) had nothing to do with freedom schools, but it remains a fascinating document of the civil rights campaign in Mississippi.

Pincus’s experience shooting Black Natchez in 1965 had much in common with the anthropological expeditions discussed in earlier chapters: Pincus and Neuman were venturing into what was, for all practical purposes, a different culture, one in which they themselves were strangers and in which they could not assume they’d be out of harm’s way. One important difference, of course, was that whereas Gardner and Asch could remain essentially neutral during the conflicts they documented in Dead Birds and The Ax Fight, Pincus and Neuman were resolute supporters of black liberation; indeed, that was the reason they were excited to undertake this project. And their presence as young white men living among and filming Natchez blacks announced this ideological commitment.

During their forty days shooting in Natchez, Pincus and Neuman worked in the tradition of Frederick Wiseman’s brand of direct cinema, struggling to remain as invisible as possible to their subjects—not all that difficult, since, like the patients in Wiseman’s Hospital (1969), the people they were documenting were embroiled in a deeply emotional, life-endangering struggle: Black Natchez documents the conflict within the black community of Natchez about which approach to the white power structure might be most effective for improving the situation of local blacks. Older, financially more established businessmen were nervous about confrontational strategies; a younger group was committed to large-scale nonviolent marches; and a third group was interested in establishing a secret cadre for taking guerrilla action against the Ku Klux Klan. A second film, Panola, not completed until 1970, was also a product of the Natchez shoot.18 Panola is a 21-minute portrait of Panola, a wino who hides his fury about racism within an off-the-wall performance: “He said the only way to be free in Natchez is to make people think you’re crazy.”19 Both Black Natchez and Panola reveal Pincus’s fast-developing skill as a cameraman. Throughout Black Natchez Pincus’s ability to work in-close with those he films is obvious, and Panola ends with Panola’s astonishing performance of his existential agony, captured in a nearly 2-minute shot filmed with remarkable dexterity, as Panola offers a tour of the small shack where he and his large family live.

Pincus and Neuman’s second project also began as an attempt to document a different culture, in this case the hippie commune culture that was developing during the late 1960s: “We chose Harry’s commune. One of the reasons was that a lot of people said it was a very good commune, and it represented what people thought was the best happening in San Francisco.”20 Unfortunately, this commune was breaking up just as their shooting got underway, and as a result, they chose to focus on the daily life of a single hippie family—Harry, Rickie, and their son Joshua—and the result was One Step Away (1967). Pincus and Neuman were also rethinking their approach to documentary in a direction that would culminate in Pincus’s decision to make Diaries (1971–1976). While in Black Natchez Pincus is at pains to suppress all evidence of his own presence and his own attitudes about the unfolding events, except insofar as the shaping of the footage implicitly reflects these attitudes, in One Step Away, his conclusion that the hippie way of life was not really all that different from conventional American life, that in many instances it was only an exaggeration of the conventional, is evoked by his use of the rather sardonic texts that introduce the various sections of the film. In large part, like Black Natchez and Panola, One Step Away reflected the direct-cinema approach Wiseman was developing, but in this instance Pincus’s subject was the daily life of a real family, again filmed in-close with considerable intimacy, this time in a manner implicitly revelatory of the filmmaker’s attitudes.21

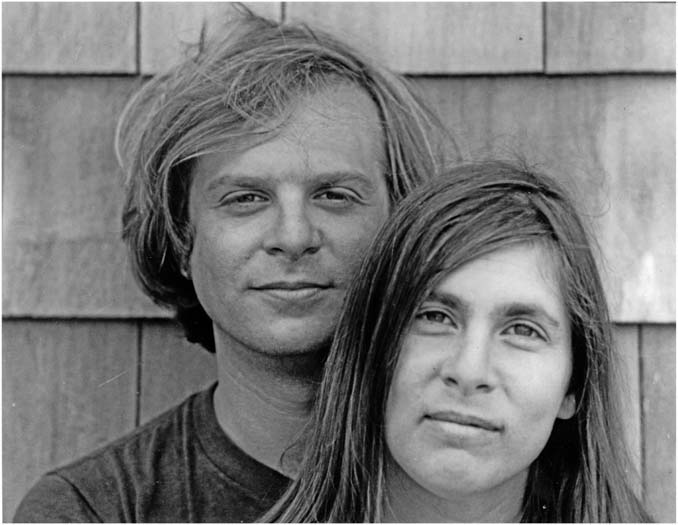

Even if in retrospect it seems evident that Pincus’s earlier films were gradually becoming more personally revealing, Diaries (1971–1976), begun once Pincus was teaching at MIT, represents a radical shift in his approach to filmmaking: a commitment to use portable sync-sound technology not to film a far-flung cultural group or set of sociopolitical events but to record and interpret his own personal life within a period of experimentation and change. During 1971, when Pincus began to shoot what would become Diaries, he and Jane Pincus, a committed feminist and one of the founders of the Our Bodies, Ourselves collective (and one of the producer/directors of Abortion [1971]),22 had agreed to transform their eleven-year marriage by opening up the possibility of exploring sexual and emotional relationships with additional partners while remaining married to each other: “The notion that no one person could fulfill another’s needs (whatever that meant) was in the air.”23 This decision was made essentially in tandem with Ed Pincus’s decision to document what would happen to their marriage and their children over an extended period (fig. 19).

Pincus devised a plan to record footage of his personal life, as uncompromisingly as possible, for five years, then wait another five years before editing what he had shot—though at the outset what editing might entail was ambiguous. Pincus’s ten-year plan can be read as a reaction to the tendency of cinema-verite filmmakers to focus on particular events unfolding in a very limited time frame: “A very important part of the Diaries project was wanting to see what changes happened over a five-year period in people’s lives, in the tenor of their politics, and perhaps in the way a filmmaker shoots.”24 In the end Pincus would adhere to his plan; he would shoot until 1976 and wouldn’t finish editing what he had shot until 1980. Because Diaries has been out of general distribution since the early 1980s, the following discussion includes more description of what occurs in Pincus’s inventive and influential personal documentary than might be necessary were the film better known.

FIGURE 19. Ed and Jane Pincus during the shooting of Ed Pincus's Diaries (1980) in the early 1970s. Courtesy Ed and Jane Pincus; photograph: Edna Katz.

Diaries was released as a 200-minute personal epic, divided into five unequal sections. “Part One,” subtitled “Christmas eve 1971,” is 52 minutes long. It begins in medias res with Ed and Jane dealing with the reality of Ed’s filming (JANE: “I feel like I’m sacrificing myself for your film; I don’t consider it my film. Get you mad?”; ED: “Doesn’t make me happy”; JANE: “Tough shit”), with Ed involved in a romantic relationship with Ann Popkin, and with Jane and Ann working to deal with their discomfort with this situation. When Ed and Jane leave Cambridge to visit David Neuman in California, Jane struggles with feelings of inadequacy that she has apparently been dealing with for years, and though she can joke about Ed’s lover—“She’s a very nice girl,” she tells David—the situation also means “a lot of agony for the wife.” When Jane returns to Cambridge to rejoin their children, Ed stays in a cabin owned by Jim and Clarissa McBride, where he takes mescaline: after a shot during which Ed films himself in a mirror (reminiscent of similar shots in McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary), the repeated intertext “sometime between 5:00 and midnight” expresses his loneliness during the mescaline trip. At the end of this sequence Jim McBride films Pincus trying to deal with what seems to have been a long and unpleasant evening.

Once Ed returns from the “trip” within his trip, the remainder of part 1 immerses viewers within the busy-ness of everyday life at work (the office of the Film Section at MIT is introduced briefly, along with Pincus’s colleague Ricky Leacock); and Diaries cuts directly from one aspect of his life to another: Pincus’s son Ben has stitches taken out of a finger; Jane considers a tubal ligation; David Neuman and Ed visit an old friend who works at Simon & Schuster; Jane leaves for Paris to spend time with her lover Bob; Ed spends time with Ann; Jane returns, pregnant, and plans to abort the pregnancy (ED: “So it’s like Bob’s kid?; JANE: “Yes, but it’s not a kid, it’s an abortion”); Ed documents anti-war demonstrations, attends a therapy session; and Jane and Ed travel to New York State with their friends Emmanuel and Aliza, who is also aborting a pregnancy; the men talk with each other and, after the abortions, with the women. The abortion sequence is presented without melodrama, indeed as a kind of idyll: flowers are blooming everywhere. Throughout part 1 (and generally throughout Diaries), Pincus moves from one part of his life to another via direct cuts—a way of suggesting the simultaneity of all these ongoing, developing relationships and activities.

Near the end of part 1, as Jane is driving Ed to Ann’s house, they discuss the fact that they are now living apart (Ed has moved into his office at MIT). Although each of them has had several lovers, both, says Jane, struggle with intimacy; indeed, she has realized that her tendency to sneeze is an expression of her need for more connection than she generally feels with Ed. During Ed’s subsequent visit with Ann, she confirms Jane’s analysis (“You’re seeing a lot of women to escape your real life problems with Jane”). Life goes on for the MIT Film Section (Ed records a meeting in which Ricky Leacock explains how much a planned renovation of the Film Section’s building will cost), and part 1 concludes with a monologue by Ed—the only such monologue in the film—during which he speaks to the camera, explaining that he has moved into his office because he feels he cannot live up to Jane’s demands and that he hasn’t been shooting film recently. He is interrupted by a phone call from Jane, and they discuss seeing a marriage counselor. In the final shot of part 1 Ed films Ben, the Pincuses’ daughter Sami, and Jane in their bedroom at home.

While self-revelation (albeit within highly controlled and usually highly synthetic situations) has become the stuff of reality TV, during the five years when Pincus was documenting his and his family’s experiences, his and Jane’s openness involved a continual confrontation of convention. Ed and Jane Pincus had grown up during the 1950s and early 1960s, an era when secrecy was endemic in middle-class American life (Todd Haynes portrays this quite accurately in Far from Heaven [2002]). For their generation (this is also my generation) virtually everything about one’s family life, from how much money one made to the nature of one’s sexual activities, was “personal.” Indeed, one important aspect of the youthful rebellion that characterized the late 1960s and early 1970s was the refusal of many young and middle-aged people to continue being secretive about their beliefs and activities or to accept secrecy about governmental policies that directly affected them: the release of the Pentagon Papers was a macrocosmic version of what was happening within the microcosm of many American families during those years. Two quite different reflections of this determination to be open and honest are evident from the beginning of Diaries. One is the frequent nudity, of Jane, of Ann, of Ben, and of Ed himself. In general, this is not exploitive nudity—though clearly Ed takes pleasure in Jane’s body. Often it is evident during a particular shot that Jane is nude or partially nude, but there is no effort to expose her. Both Ann and Ed are seen nude in Ed’s office loft early in the film, but here the camera is presumably mounted on a tripod on the floor of the loft, angled up, so that we see that they are nude together, but there is no attempt to reveal either of them in any detail. And sometimes Ben and his playmates are nude, in a bathtub or playing, but this is the nature of living with young children and, again, receives no undue focus.

A second kind of openness involves the ways in which Pincus makes visible (and audible) the filming process itself. The first conversation in the film reveals Jane’s concern about looking beautiful for the camera and that she feels judged by it (“I have a mustache,” she laughs, in an early close-up), and Ben’s first line in the film is “What’s that wheel?” Ed responds, “That’s the camera.” The sound of the camera running is audible, sometimes more, sometimes less, throughout Diaries (1971–1976) and becomes a motif. While there was nothing new in the 1970s about drawing attention to the apparatus of filming—many avant-garde filmmakers had engaged in explorations of the apparatus of the camera and projector—Pincus’s decision to maintain the audience’s awareness of his process in these ways was still unusual in the world of American documentary filmmaking: in the direct cinema of Wiseman, the Maysles Brothers, and others, the filmmaker’s goal was to be as invisible as possible, especially insofar as the camera and sound equipment were concerned.

During the original shooting and within the finished film, Pincus doesn’t merely depict the nature of his relationships with Jane, Sami, Ben, David Neuman, Ann Popkin, and the others included in the footage, or reveal a particular change or transformative moment in a relationship. Pincus’s five-year plan allows him to track the continually shifting nature of his relationships with family, lovers, friends, as well as the gradual changes in how his subjects (including Ed himself) interact with the camera and his filming. In other words, the life Pincus is revealing is a reality in continual flux within which he and Jane test, and retest, their marriage and their idea of marriage, adjusting to each other’s changes on the basis of what they learn during each new adventure. They exemplify William James’s understanding of reality as always “still in the making,” always awaiting, “part of its complexion from the future.”25

Part 2 of Diaries, the longest in the film (72½ minutes), immediately reveals how much things have changed during the months between Ed and Jane’s considering a marriage counselor and the summer of 1972, when they have rented a house in Vermont by a small lake. After the personal (and political) turmoil of late 1971 through early 1972, the opening section of part 2, which takes place in the Vermont landscape, seems idyllic, even Edenic. Early on, after several family scenes, including one in which Jane tells her visiting father how disrespected she feels by his disapproval of her hanging her batiks in the kitchen, we realize that although Ed stands up to her father (FATHER: “Ed, how did you feel about your wife turning your kitchen into a studio?”; ED: “I really liked it”), it has not been clear during the first hour of Diaries that Jane is a batik artist. Implicitly, Ed has changed since part 1: he’s become more accepting of Jane’s creativity. A kind of rebirth seems in the air, symbolized not only by this episode but by the Pincuses’ new puppy, and by a scene during which Jane, Ann, and a third woman are lying nude in a kiddie pool, enjoying the sun (Ed, nude himself, hovers nearby; it is not clear who is doing the filming). Around this same time, it seems that Ed has been physically involved with both Jane and Ann, together; to Ed’s embarrassment, they complain about his “looming” above them during the recent sexual adventure. During this passage—and in fact all through Diaries—the presence of Ben and Sami playing and fighting is pervasive, part of the auditory and often visual atmosphere of the film, and evidence not only of the continual change in the children and in their relationships with each other, but of Ed’s and Jane’s commitment to rethinking their marriage within a commitment to family.

A jump through time brings us to “fall 1972” and a brief passage during which Jane is working on batiks and Ed is filming. Jane, whose relationship with Bob seems in hiatus, explains that she was sexually open with him in ways she has never been with Ed. This is followed by “South by Southwest,” a nearly 30-minute interruption in the Pincus family narrative during which Ed and David Neuman travel from California through Arizona (Tucson, where Ed makes contact with a now-married former lover and her newborn), New Mexico (a bridge over the Rio Grande near Santa Fe, and Taos), Arizona again (the Grand Canyon), and Las Vegas. After this interlude, Pincus returns to Cambridge, where Jane is learning the flute, and where Ed films the broadcast of his appearance on Robert Gardner’s Screening Room and spends time with Christina, apparently a new lover, and Ann. About two hours into the film, Diaries (1971–1976) announces an intermission.

Pincus’s determination to record the realities of a nuclear family undergoing experimentation and change is quite radical (of course, what is radical here is not simply the couple’s taking lovers but their openness about this process, both with each other and with the camera and implied audience), but it is not Pincus’s only commitment as filmmaker. His documenting the development of his family life is interwoven with a second commitment, this one specifically cinematic: he means to explore and redefine the relationship between filmmaker and subject within film history, and especially within the history of cinema verite filmmaking. From the beginning of Diaries (1971–1976), Jane (and Ben and Sami) are the objects of Ed’s filmic gaze, but he himself is also on screen regularly: twenty-three times during parts 1 and 2. In three instances, Ed films his reflection in a mirror, and in two others he has set up the camera in order to film himself, but in most instances, someone else is holding the camera: Ann, during their conversations; Jim McBride, during Ed’s mescaline trip; David, when Ed is driving in Tucson; and other people in other instances. While we are often not sure who is filming Ed, it is obvious that the documentation of his open marriage involved also the opening up of the filming process itself: that is, in Diaries (1971–1976) the marital experimentation and the filmic experimentation are analogous to one another.

Subsequent to the intermission, the mood of Diaries changes: part 3 (20¾ minutes) opens, just as part 1 does, with a mirror shot in which we see both Ed and Jane, but in this instance, Ed’s hand is seen in the foreground giving Jane a ring, as Ed says, “Will you marry me?” The remainder of this section of the film seems to confirm the Pincuses’ comfort in the ongoing development of their domestic life, and this development is apparent in a variety of ways: for example, Jane has finally gotten the tubal ligation she considered during part 1, and much of part 3 is focused on Ed’s cousin Jill’s wedding in New York, a traditional wedding during which Ed, Jane, the children, and Ed’s mother function in conventional ways. The adventurousness of the open marriage is alluded to during two passages focused on Christina, but Christina’s comments that conclude this section of the film—“Everybody has to learn that they are alone. . . . You gotta learn how to be alone!”—seem contradicted by Ed’s immersion in both nuclear and extended family.

Part 4 (30 minutes) confirms the changes in part 3; indeed, the opening of part 4 (“winter 1974—a broken leg”) seems a further counterpoint to Christina’s comments on having to learn to live alone. Pincus, now with his leg in a cast, films the family functioning around him. Jane’s batiks are hanging here and there, more visible than at any previous moment in the film; and her developing creativity is also emphasized by the motif of her playing the flute: we can hear how she has improved (the ongoing improvement in her ability as a musician remains a motif). In the following sequence, when Ed visits the MIT Film Section office on crutches, we can see that a romance is brewing, or is underway, with a woman there; and it is evident that an involvement with other lovers continues (near the end of part 4, Ed and Jane talk about Ed’s feeling more temptation in the city than in Vermont).

Part 4 also confirms Pincus’s increasing openness about himself, his deepening engagement with domesticity; and it marks a change in his thinking as a filmmaker. Early in part 4, Ed films (and has someone else film) the process of rehabilitating his leg; we see various men, nude, undergoing whirlpool treatments in a training room. Also during part 4, Pincus includes a shot (again a shot made by someone else) of himself teaching at MIT (he refers to Rossellini’s Voyage in Italy [Viaggio in Italia, 1953]: “The action . . . is the . . . small moves between couples”), and at a party we see Ed, talking with Ricky Leacock (the conversation filmed by a third person) about the somewhat different costs of being a private versus a public person. In part 4, Ed also seems increasingly appreciative of his family life. Ben’s curiosity about filmmaking becomes more obvious, and Sami is developing as a performer; in several instances she and a friend do song and dance numbers for the camera. The obvious intimacy of this nuclear family is encapsulated in one noteworthy composition midway through part 4: parts of Ed’s, Jane’s, and Ben’s bodies are intertwined on a bed; they seem almost a single being.

The change in Pincus’s thinking as a cinematographer is evident in a conversation he has early in part 4 with Christina, who wonders what Ed is learning about his life from recording footage for Diaries. Pincus’s response—“It’s interesting, light’s just become more important”—annoys Christina: “That’s not what I’m asking! That disgusts me that that’s your answer! That’s a technical answer to this philosophical question. . . . I mean what about just this nitty-gritty sort of human aspect of your life? It has nothing to do with light!” While, in the end, Pincus does admit that he’s found out “a lot about myself; I just don’t want to talk about it,” his immediate response to Christina’s query is, “I don’t know if you’re right about that,” which is implicitly confirmed by his focusing on patches of reflected light on the wall of Christina’s loft, and, at the end of the conversation, by his transitioning from the window in her loft to a window in his Vermont home (actually, Pincus’s awareness of light is quite evident throughout Diaries). This interchange between Ed and Christina reflects a gradual change in emphasis from the nitty-gritty of Ed’s and Jane’s working on their relationship to the physical beauty of Vermont and to Ed’s increasingly idyllic engagement with his children and Jane so evident in part 5 (“filming every day in January—the small events of days at home”), which begins with an unusual voice-over: “Today is January 1st and I’m going to try to film every day” (unusual because this is the first voice-over in the film spoken within the present, rather than from the distance of the editing process).

While part 5 (22 minutes) is increasingly idyllic, this is not because the Pincuses have retreated from their experimental marriage into conventional monogamy. Early in the section, Ed asks Jane about her upcoming visit to Joe. Jane responds, “It’s piquant, it’s unusual, it’s an adventure, it’s a risk; it will not jeopardize our marriage, but it will change it in small ways.” When Ed asks why, she responds, “I’m not sure. . . . I somehow feel sexier already, toward you . . . and I feel also very thankful that I can have that kind of adventure, and recognize it as some kind of adventure and that there’s maybe some dangers, but—and maybe I’m being stupid, I don’t know—but I guess I feel pretty good about it.” The return to a series of upbeat domestic moments confirms the idea that Jane’s adventure not only does not endanger the marriage but may invigorate it.26 This idea is cinematically confirmed soon after this conversation when Jane, in a flirty manner, says to Ed, who is filming her, “You look cute. Can I take a picture of you?” Ed says, “Sure,” and we see that the camera changes hands; Jane pans around to Ed, who is sitting at a desk, naked from the waist down.

As has been suggested, throughout Diaries (1971–1976) Ed opens up his process by releasing his camera into many other hands. This, however, is the first instance where we witness the transfer of control from his hands to another’s. That Jane has asked to make this image (another first in the film—though we assume she is filming in other instances) brings Diaries full circle from Jane’s voicing concern at the opening of the film about the presence of the camera and being the object of its gaze. And it creates a cinematic “ring” (echoing perhaps the ring Ed gives Jane at the beginning of part 3) that joins the man and woman as co-creators of both a marriage and a family and as makers of the film we are watching.

Part 5 concludes with four distinct but related sequences that function as a coda to Pincus’s domestic epic. The first of these, titled “Summer 1975—freeze tag,” focuses entirely on Ben (fig. 20), Sami, and some other children playing freeze tag in a lovely, green-glowing Vermont landscape. The very idea of freeze tag evokes the larger project of Diaries (1971–1976), which freezes a series of moments in several intertwined lives; and a shot of Ben trying, without too much success, to freeze in position echoes the nature of the lives depicted in the film: Ed and Jane work to maintain their stability as a couple and as parents within a continually changing social landscape. The freeze tag sequence also confirms the film’s increased focus on Ben and Sami. When Ben throws a tantrum because he doesn’t want to be “it,” Sami functions as his therapist, explaining that being “it” is “part of the playing, part of the whole game, and if you don’t be it, it’s no fun for anyone else. You gotta be it sometimes, Ben, just try it!” I read this interchange as not only a poignant record of the interaction between two siblings (Ben does become involved with the game), but also as a metaphor for Ed and Jane: early in the film, Jane seems the one who is struggling with both the experiment of open marriage and with this experimental film; in the final sections, and despite the strength of their ongoing relationship, Ed is “it” and must deal with Jane’s going off with other men.27

FIGURE 20. Ben Pincus in Ed Pincus's Diaries (1980). Courtesy Ed and Jane Pincus.

The second sequence begins with Ed’s voice-over announcing, “That summer, we decided to live permanently in Vermont,” followed by a lovely sequence of Jane walking through a snowscape outside of their Vermont home in beautiful winter light. Pincus explains how this move has involved him in commuting from Vermont to MIT and that part of the reason for this change in their lives is that “Dennis Sweeney had become a problem in my life. . . . Dennis had turned vicious and now threatened Jane, Ben, and me”; “Five years later, in March 1980, Dennis walked into Allard Lowenstein’s office and shot and killed him.” This is followed by a conversation between Jane and Ed—they are in a car; Jane is driving—revealing their anger and frustration with Sweeney and his threats. This is the final instance in the film of what has been a motif throughout: filming conversations in a moving car; and like so many other motifs in Diaries this one functions both literally and metaphorically. In a variety of senses, Ed, Jane, Sami, Ben, and their friends and extended family members are continually “on the move.” Sometimes one or another person is driving this movement (in this final instance, Jane is driving the car, though Sweeney is implicitly driving the Pincuses into a new kind of life), but as in freeze tag, the lives Pincus portrays are made up of a series of moments of stability within ongoing social, political, physical, psychological, and emotional change.

Immediately after Ed and Jane’s conversation about Sweeney, an intertitle, “summer 1976—a friend has terminal cancer” introduces a brief sequence that reveals Ed’s visit to his friend David Hancock’s home and Ed’s subsequent sadness about David’s illness. This is followed by a cine-memorial to David, a series of five shots, beginning with David, looking very gaunt, in a bed covered by a blanket with red edging. This bit of red is carried into the shots that follow: a red geranium on a window sill; a view out the window at distant trees with leaves changing that pans to a crayon drawing of the geranium; a ground-level shot of David’s burial in which several women have red skirts; and finally, a rainy fall day and a tree with leaves turned red. This “bouquet” of red is Pincus’s tribute to his friend and to the passion for life and for Vermont that David had apparently always exhibited.

The conclusion of Diaries (1971–1976) is a 3-minute shot of Ed, Jane, and Ben, in the early fall after David’s death, outside their Vermont home, on Yom Kippur.28 As the credits roll, Jane is cutting Ed’s hair and Ben is whining about Sami’s bothering him (Sami is heard, behind the camera, defending herself, though we never see her during this shot).29 As Jim Lane has suggested, “The cutting of Ed’s hair suggests not only a renewed bond between the couple but also a transformed Ed, an Ed more content with his revised role as husband and father. His unique relationship with the camera (which he warns his children not to knock over during the scene) underpins this realization. This relationship has changed over time, as has his relationship with his family.”30 Throughout this final family portrait, a reflection on the left side of the frame appears rhythmically, a final emblem of cinema itself and of Pincus’s decision to embed the filmmaking apparatus within the reshaping of his personal life and the lives of his family. This final image also encapsulates what Pincus knew by 1980, when he finished editing Diaries: that he had not only documented a redefinition of marriage and family, and rethought how filmmaking could function within domestic, everyday life, but had exited from filmmaking altogether. Pincus would leave his teaching job at MIT in 1979 and, in concert with Jane, would establish and manage Third Branch Flower, in Roxbury, Vermont. He wouldn’t finish another film for twenty-seven years.

Flannery O’Connor’s belief in “the possibility of reading a small history in a universal light” seems relevant to Pincus’s quest to document the particular changes he and his family went through during a half-decade, for while Pincus’s focus is even more intimate than what O’Connor would call “local,” this intimacy represents a substantial portion of a particular American generation during an unusually eventful extended moment.31 During the early 1970s many thousands of young married couples (my present wife and I were among them) experimented with new definitions of marriage, definitions that challenged traditional monogamy and conventional assumptions about privacy. Pincus is one of few filmmakers who has chronicled, from inside the experience itself, this generation’s experimentation and the ways in which their experiments affected the day-to-day lives of couples and families.

Ultimately, Pincus’s revelations in Diaries (1971–1976) have much in common with what John Marshall reveals in A Group of Women, A Joking Relationship, and A Kalahari Family, what Robert Gardner reveals in Dead Birds and Rivers of Sand, and what Timothy Asch reveals in Dodoth Morning, A Father Washes His Children, and even perhaps in The Ax Fight. All these films reveal the lives of families and their attempts to find moments of stability and intimacy in a continually changing environment within which the fact of filmmaking itself is emblematic of both transformation and a hunger for continuity.

During the interim between his shooting and editing Diaries, Pincus collaborated with Steven Ascher on Life and Other Anxieties, which was shot during 1976–77 and completed in 1977 (the two men would later collaborate on two editions of The Filmmaker’s Handbook, first edition published in 1984).32 Life and Other Anxieties begins more or less where Diaries ends, with a prologue during which Pincus returns to the summer and fall of 1976, when he discovered that David Hancock had cancer of the liver. In voice-over he explains:

Six months ago I hugged David and he felt strong like an oak tree. The next time I talked to him, his voice was distant: he told me he had cancer of the liver. He had been planning to go to Europe to make a film; and now he wanted to do a film about his dying, about the brutality of the medical establishment. He’d asked me to help him; I was never able to do that. When Steve came to visit, I asked him to shoot for me. I tried to give David’s death meaning, but none comes. David was a good friend; what more can I say?

Footage of Hancock at his Vermont home is followed by Pincus’s indicating that he has received a grant to make a film in Minneapolis during the following winter: his plan is to attract strangers to the project and to film whatever the strangers indicate they would like him to film. Before he and Ascher travel to Minnesota for the winter-spring, Hancock is filmed one more time (he is on the phone, looking very frail, saying, “Looks like it’s all over”); his funeral follows. Ascher and Pincus then travel to Minneapolis, and the remainder of Life and Other Anxieties intercuts between the filmmakers trying to convince people to be involved in their project and the various events they end up being a part of.

Except for the sequences involving Hancock (and footage shot when Pincus flew home to Vermont for ten days—Jane, Sami, and Ben make appearances), the personal dimension of Life is the personal struggle of Pincus, who did the shooting, and Ascher, who took sound, to get the film made: this involves a range of personal interactions with strangers, evocative in a general sense of Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s Chronique d’un été (Paris 1960) (Chronicle of a Summer (Paris 1960); 1961). At one point, in desperation, Pincus and Ascher follow random people around, filming them; but they do find their way to a variety of willing subjects and are able to weather the brutal Minnesota winter (they film at a party on an evening when there is a ’80 degree wind chill). The result is an engaging panorama of men and women, young and old, black and white, working and playing in the Twin Cities area. The film is dedicated to Hancock, who was a Minnesota native.

As this book goes into production, Pincus is at work on what might be considered a further response to Hancock’s death, and in particular, to Hancock’s asking Pincus to produce a film about his (Hancock’s) death—a request Pincus didn’t feel he could grant (Life and Other Anxieties seems, in a sense, an atonement for this decision). In 2012, Pincus learned that he had AML (acute myeloid leukemia), a rare and dangerous form of leukemia. His response, a response that echoes Hancock’s, was to throw himself into a film about facing his own imminent mortality. The tentative title is The Elephant in the Room; Pincus is co-making it with Lucia Small.

ALFRED GUZZETTI: FAMILY PORTRAIT SITTINGS

Here was a subject (my family) that I already knew a lot about, and I felt that this offered an opportunity to make a film that went deeper, into more detail, than the cinema verite films, including the personal documentaries that were being made. Ed Pincus was committed to a very pure kind of cinema verite; Diaries is an exploration of that purist point of view. Ed has always been tactful enough not to talk about Family Portrait Sittings, but I suspect he didn’t like it.

ALFRED GUZZETTI33

Like Ed Pincus, Alfred Guzzetti was drawn to family as a subject for documentary because, like so many filmmakers coming of age in the late 1960s and early 1970s, he believed that the personal is the political, and because a focus on family would allow him to circumvent what he had come to feel was one of the crucial limitations of the forms of documentary that had become popular during the 1960s and early 1970s: “At the time, I felt that cinema-verite documentary, which was all the rage, was nearly always superficial—I sometimes still feel this way. One reason is that people who make cinema-verite documentaries encounter their subjects in the way that Flaherty prescribed: practically without preconception. This is wonderful in one sense—it allows for certain kinds of discoveries—but on the other hand, diving into something new and exploring doesn’t take you very deep, given the amount of time you have to learn about your subject and the amount of shooting time you usually have.”34 Making a film about his own family, Guzzetti reasoned, would allow him to come to his subject with long-term experience and considerable knowledge, and it would allow for an extended shooting schedule, enough time to produce something substantive. Unlike Pincus, however, Guzzetti decided to focus not on an ongoing experiment in redefining the experience of family, but rather on the history that had brought his family to its present situation, and in general, on the way in which families come to represent themselves over time.

Family Portrait Sittings divides into three approximately equal parts, each of which has somewhat different emphases and reflects different aspects of what Guzzetti came to understand about his family during his three years of shooting. Part 1 begins with a brief foreword during which we hear Domenick Verlengia, Guzzetti’s maternal great-uncle and the oldest surviving member of his family, in voice-over, describing his decision to leave Italy and emigrate to the United States. The excitement of this decision is suggested by a series of forward tracking shots through South Philadelphia streets. The final tracking shot comes to a stop as Verlengia says, “And I arrive here in Philadelphia the thirteen of May, 1921.” The film’s title is then superimposed over a close-up of hands sewing a man’s suit coat (Verlengia was a tailor), which is followed by a listing of those whose voices chronicle the family’s history: Guzzetti’s great-uncle; his grandmother, Pauline Verlengia; his paternal grandfather’s cousins Guido and Savaria D’Alonzo; his own parents, Felix and Susan Verlengia Guzzetti.

During the remainder of part 1, the focus is on the background of the two families. Domenick Verlengia describes the history of his family up until his emigration to America: his focus is the intelligence of his mother, who died young, and brother (Guzzetti’s grandfather), who knew how to make a suit by the time he was fourteen years old. His narration of the Verlengia family history is accompanied by forward tracking shots through Abruzzo, Italy, with stops in the locations mentioned. Verlengia’s review of his family history is followed by the Guzzetti cousins’ voice-over review of their family’s history (translated by subtitles), beginning with a story from 1365 and ending with two brothers, Quirino and Nicolino, coming to America. An extended passage of black-and-white photographs of the two families follows, with Guzzetti’s parents, grandmother, and uncle describing the families’ early years in Philadelphia, years that led to the union of Susan and Felix. Interrupting this photo montage, in two instances, are sync-sound moments from interviews first with Pauline Verlengia and then with Domenick, and finally with Sue and Felix, sitting on a couch in their apartment, talking about their courtship (fig. 21). Black-and-white home movies and photographs of their wedding bring part 1 to a close.

Part 2 focuses on the Guzzettis’ early married life: the struggle for jobs during the Depression; Sue’s decision to go to teacher’s college; Felix’s employment by Economical Coal Company and his interest in photography; Domenick’s tailoring work; and the arrival of children: Alfred in 1942 and Paula in 1946. The emergence of Felix and Sue’s family is formally signaled by Guzzetti’s inclusion of his father’s color home movies, which become a subtext of Family Portrait Sittings from here on, a kind of secondary chronology of events represented by artifacts produced during this chronology. The motif of Guzzetti’s parents sitting on the couch (and Domenick Verlengia sitting in a chair), speaking to Guzzetti behind the camera, becomes central in part 2, as the parents discuss their history and their differences in temperament and attitude over the years, along with some of the sacrifices their family required: most obviously, their move from South Philadelphia to a new neighborhood where the children could have more room and better schools—a neighborhood, it turns out, neither parent is comfortable in, though the children thrived. Sue’s and Felix’s very different personalities and the resulting mixture of agreement and conflict during their years together are echoed by their changing positions on the couch: sometimes they sit next to one another, at other times, at opposite ends of the couch. Part 2 ends with Sue and Felix discussing their relationship to religious belief (both, in somewhat different ways, make clear their ambivalence) and with a silent, color shot of young Paula eating cereal at the kitchen table.

FIGURE 21. Susan and Felix Guzzetti on couch in family home in Alfred Guzzetti's Family Portrait Sittings (1975). Courtesy Alfred Guzzetti.

Part 3 continues the motifs established in part 2: Sue and Felix Guzzetti’s commentary on their history together, Domenick Verlengia’s reflections on his involvement with his niece’s family, accompanied by the color home movie records of the development of the Guzzetti children: like most home movies, these are focused on birthday parties and other family get-togethers. More fully than earlier parts of Family Portrait Sittings, however, part 3 reveals struggles with issues that were becoming increasingly important in the 1950s and 1960s, including Sue’s emerging as what Domenick Verlengia describes as the “prime mover” of the family and her own ambivalence about her “aggressiveness” (during this section of the film, Sue and Felix are arranged on the couch so that Sue is in the very center of the frame, and Felix to her right). Later in the section, the elder family members discuss the Vietnam War and President Richard M. Nixon (Domenick Verlengia is outspoken in his contempt for Nixon and the war), and various forms of more local political struggle, including Sue on a picket line demonstrating for better working conditions for teachers. In a break from strict chronology, Guzzetti’s grandmother asks Domenick Verlengia to “tell Alfred about the story when pop died, how you took over the house,” and Verlengia describes the political discussions he once had with his brother.

Part 3 ends with a sequence during which we see both Felix Guzzetti and Alfred shooting film, a kind of shot/countershot between two generations and two modes of filmmaking (Felix is shooting with a small 8mm camera; Alfred in one instance with a CP16 and later with a professional grade Arriflex), followed by Felix’s comments on his son’s filmmaking:

I’ve never seen anybody who’s as enthusiastic over making these films that have no commercial value at all, actually have no . . . they don’t, Alfred. You can never make any money out of it. You know that and I know that, and not once has anyone of us said, “Well, he is crazy, he is doing all this work and he gets no commercial rewards.” But we know how you feel about these things and we know you’re happy in it, and that remark will never, never come out of me, that you’re crazy for doing them. . . .