6

Ross McElwee

As of the new millennium, no personal documentary filmmaker had become better known than Ross McElwee. Despite what we might imagine was the influence of Ricky Leacock and Ed Pincus at MIT and of Alfred Guzzetti, McElwee’s teaching colleague at Harvard since 1986—all of whom abjured or at least avoided voice-over narration in documentary film—McElwee has become the most inventive explorer of voice-over in the history of personal documentary. Indeed, if his approach to narration no longer seems as distinct as it once did, that is because so many working in personal documentary in recent years have been under his influence. McElwee is also among the few filmmakers who have entirely devoted themselves to personal documentary. Aside from youthful experiments and from his earliest feature films—Charlene (1977) and Space Coast (1979, co-made with Michel Negroponte)—and one collaboration with Marilyn Levine (Something to Do with the Wall, 1991), McElwee has been devoted to personal documentary for going on thirty years.1

McElwee’s seven personal documentaries reveal a filmmaker exploring, on one hand, the nature of his personal relationships with family members and with friends and colleagues as they have developed over time, and on the other, the continually evolving ways in which McElwee’s self-identification as a filmmaker has affected these relationships. Further, since each new McElwee personal documentary builds (explicitly and implicitly) on the previous films, those who continue to follow his career are involved with his work on a meta-level: each new experience with McElwee’s life and filmmaking causes us to rethink the long chronicle of McElwee’s experiences and our reactions to it over time. As spectators, we are learning not only from McElwee’s experiences but from our own experiences with him. Indeed, on a certain level, McElwee as filmmaker seems more intimate with us than he is with those he films. Decade after decade we have been his trusted confidants, continually learning not only about McElwee, but about our ongoing, always evolving “relationship” with him.

FINDING A MUSE: CHARLEEN

In a way, by having made The Blue Angel, the most widely circulated German film, I had made a German woman the toast of many lands, and, if nothing else, had spread good will for the Germans at a time when they were not very popular.

JOSEF VON STERNBERG, FUN IN A CHINESE LAUNDRY2

Ross McElwee has become synonymous with autobiographical filmmaking, and his mentoring of filmmakers and films during his many years teaching at Harvard has probably had nearly as significant an impact on the field as his films. At MIT both Ed Pincus and Ricky Leacock were crucial influences. Ed Pincus’s Diaries was important for McElwee—“I’m sure I was influenced by it in all kinds of ways”3—and when he graduated with his master’s degree in 1977, he worked as Pincus’s teaching assistant for an additional year and a half. Ricky Leacock, especially his Happy Mother’s Day (1963) and his general attitude toward filmmaking, were also important. McElwee implicitly pays homage to Leacock by having him speak the opening narration in Sherman’s March (1986) and by having him appear in Time Indefinite (1993), and he has made his appreciation explicit: “When I was at MIT, Ricky was always irreverent, always encouraging us to do films for ourselves, to do films that were not conceived of as commercial entities. This is not what you hear in a lot of film schools, where you’re encouraged to produce films that will get you jobs in public television, or in commercial television or Hollywood. Ricky was always very caustic and irreverent about those reasons for making films.”4

Both Pincus and Leacock seem to have agreed that their job was to see that those men and women who wanted to make films got to make them (often whether they were matriculated at MIT or not), and by the time he left MIT, McElwee had shot footage for the three films that would, each in its own way, provide him with the cinematic approaches and elements that, combined, would make his films distinctive and memorable: Charleen (1979), which was McElwee’s thesis film; Space Coast (1979, co-made with Michel Negroponte); and Backyard (1984), McElwee’s breakthrough autobiographical documentary.5

If it took some years before McElwee settled on the combination of cinematic elements that we now recognize as his distinctive approach to autobiographical filmmaking, one of his central themes—the American South—was evident from the beginning. Though Charleen focuses on McElwee’s good friend, Charleen Swansea, he had originally envisioned the project as a portrait of the South,

or at least of Charlotte, North Carolina, with Charleen as a witty tour guide. I wasn’t at all sure that the film would be an intimate portrait of Charleen herself, though I hoped this would be the case. As it turned out, Charleen enjoyed being filmed and was a natural performer, in the sense that even though it was simply her own life that she was performing, she always performed it with a certain élan that was very “filmable.” She enjoyed revealing her life to me and the camera. As a result, much of the Southern detail simply got eclipsed by Charleen herself.6

As McElwee would explain later, in Backyard, his move to the North, and in particular, New England—first, to Providence, Rhode Island, where he was an undergraduate at Brown, then to Cambridge, to attend MIT and later to teach at Harvard—was seen by some members of his family as a kind of abandonment of his heritage; and while McElwee has often made comic use of his subsequent difference from his relatives, his films, at least up through Time Indefinite (1993), seem to have as an implicit goal a confrontation of certain prejudicial assumptions that northerners often have about his native region.

This confrontation is evident from the beginning of Charleen, as McElwee provides information about Swansea’s unusual background, and his own relationship to her, in a scrolling text:

Charleen Swansea Whisnant taught poetry in the schools of Charlotte, N.C., where I grew up. I first met her when I was a high school student and we have since become good friends.

When Charleen was quite young, she ran away from home to find a new father, preferably a famous one. She was in turn “adopted” by Albert Einstein, e. e. cummings, and Ezra Pound.

She now publishes a literary journal and teaches in the Poetry-in-the-Schools Program.

McElwee’s reference to Swansea’s impressive (and somewhat mysterious) connection with three famous northern intellectuals is followed by a remarkable sequence of Swansea at work in the Poetry-in-the-Schools Program: remarkable, because of her obvious ease and effectiveness at working with African American young people.7

In order to model the direct expression of feeling that poetry demands, Swansea asks a young man, Fred, to stand beside her while she pretends to be someone in love with him. “I luv ya, Fred!,” she says to Fred; then, explaining to the class that a sure way to win the attention of a beloved is to enunciate specifically what one loves about him, she says, “Freddy, you smell like a melted Hershey bar, and every time I look at you, Fred, and look into your laughin’ black eyes, it makes me feel like it’s the middle of the night and ain’t nobody in the world but me and you in the dark.” That all this is done in very close physical proximity with Fred, and to the amusement of Fred and the apparent delight of the class, represents a crossing of racial barriers in a manner that, even thirty years later, can seem surprising in any sector of the United States (indeed, for those overly concerned with decorum in the classroom, Swansea’s teaching might seem dangerously “inappropriate” because of the erotic innuendo implicit in her performance of passionate attraction). If we can assume that the fear of miscegenation remained alive in the South of the late 1970s, Swansea’s teaching is a high-spirited defiance of this fear.

At least as we witness it in Charleen, the Poetry-in-the-Schools Program seems dedicated to offering young people, African American young people in particular, an opportunity to broaden their horizons. And judging from what McElwee shows us, Swansea’s mission is to move both the black and the white South in a progressive direction. This is evident during the second sequence of Charleen, when Swansea is the guest at a Bible study gathering at her mother’s home, attended entirely by older white women. Swansea describes an incident that occurred when she was trying to give a group of young people the tools to ask for what they need. When she challenged a quiet, resistant, formidable-looking young man named Peanut, sitting in the back of the class, to “tell me what you want; talk me out of my money!,” he walked up to her, pulled out a knife, and said, “Give me your money!” A fellow classmate tells Peanut, “Nigguh, put up that knife! That’s why we tryin’ to teach you to talk, so you don’t have to use that knife!,” and Swansea explains to the women’s group, “I realized that Jasper had said it better than I’d ever said it, and I think it’s really true, that those youngsters who can’t read, who can’t talk, who can’t talk you into giving them or society into giving them what it takes to live, are gonna click that knife open.” Swansea’s story doesn’t simply confirm her skill at working with African American youngsters, it demonstrates her willingness to educate an older generation of southern white women by sharing what she feels she has learned through her teaching.

That McElwee begins Charleen with these two incidents reveals his admiration of Swansea’s courage and commitment as a teacher and makes clear at the outset that he means to document Charleen Swansea within a context of the problematic racial history of the South as this history reveals itself in the present. The two sequences make clear that southerners (Swansea, McElwee, and implicitly Swansea’s mother) are aware of this history and engaged in confronting the problems it continues to pose. Much of what follows in Charleen involves Swansea, her boyfriend (we learn early on that she is separated from her husband and is living with their two children), and a racially integrated group of young people preparing, then presenting what might now be called a noncompetitive poetry slam to students in a rural school (the group at the school seems with a single exception white). Throughout Charleen it is obvious that the city of Charlotte and the area around it remain largely segregated, but it is equally obvious that there are southerners, old and young, who, with persistence, courage, and good humor, are working to confront the imbalance of power and opportunity that segregation has created.

Having demonstrated Swansea’s commitment to using poetry and her teaching abilities in the interest of progressive cultural change, McElwee focuses increasingly on Swansea’s day-to-day life, and in particular on her relationships with Ezra Pound (she is in the process of selling her Pound memorabilia in order to fund her daughter’s and son’s college education), her boyfriend Jim, her father, her children, friends, and acquaintances, and on her interactions with McElwee and the filmmaking process he has instigated. The racial issue is evident, often subtly, within each of the situations McElwee documents, though it is Swansea’s effusive, engaging personality that becomes the foreground of Charleen. During the time when McElwee was documenting Swansea’s experiences, her relationship with Jim was in flux. She and Jim argue, try to work together on the poetry slam, and following the event, break up, seemingly for good—we learn in Time Indefinite (1993) that she and Jim later married. It is also clear that Jim’s living with Swansea creates some tension with her children, Tom and Ena; Ena in particular, while part of the crew for the poetry slam, enjoys rebelling against both Swansea and Jim.

McElwee’s documentation of Swansea begins as fly-on-the-wall observation, and whatever information McElwee provides is presented in a series of brief visual texts. However, from the beginning, and increasingly as the film unfolds, Swansea engages the camera and even McElwee directly. The first instance occurs during the drive to Swansea’s mother’s home—she talks to McElwee and Michel Negroponte, who took sound for the film, about Tom being ill the previous evening and how excited she is to be visiting her mother. The camera follows Swansea to the door of her mother’s home, and Swansea holds the door for McElwee and Negroponte. Later, Swansea provides a tour of some of the Pound material directly to McElwee and Negroponte, and during later scenes often addresses the filmmakers. Midway through the film, when Swansea says that she doesn’t think she’ll stay in her job, McElwee can be heard asking, “Why not, Charleen?,” and later, after she drives her maid to the bus stop, she expresses her discomfort with her relationship with the woman (“the only person I know in my life who, when I talk to her, I don’t look in her eyes”), then, as the maid gets on the bus, asks McElwee, “Can I go?” McElwee says, “Sure.” In other words, McElwee is “present” within the film in two distinct ways: as the implicit narrator of the visual texts and as an invisible character within the scenes documented. Of course, McElwee would continue to explore and expand this combination of detachment and engagement.

Charleen concludes with two events, one professional, the other personal. The poetry concert is presented successfully in Piedmont: McElwee documents the cast and crew gathering to travel to the concert, the concert itself and the audience’s response, and the trip back. Then, following a final visual text, “After the concert, Charleen said she wanted to be alone. Several days passed. Finally, she asked us to come to her house. She had been in the hospital and now she wanted to talk to us” The film concludes with an extended conversation with Swansea, who has injured her hand by smashing it through glass panels on Jim’s door—after finding out that Jim had been “off for the weekend with a girl younger than me.” Swansea seems devastated by his leaving, but says she recognizes the realities of having a boyfriend much younger than she and claims to be excited about moving on and seeing where life will take her: “I’m gonna love it,” she laughs. The final shot reveals Swansea alone in a classroom, singing “Georgia on My Mind” backed by a limited pianist on an out-of-tune piano.

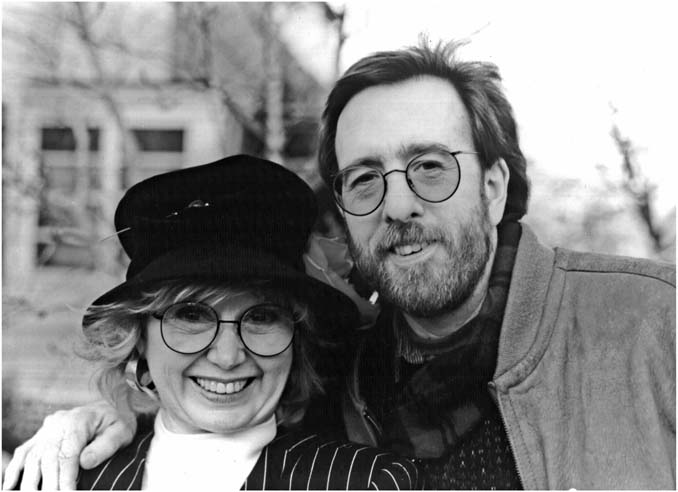

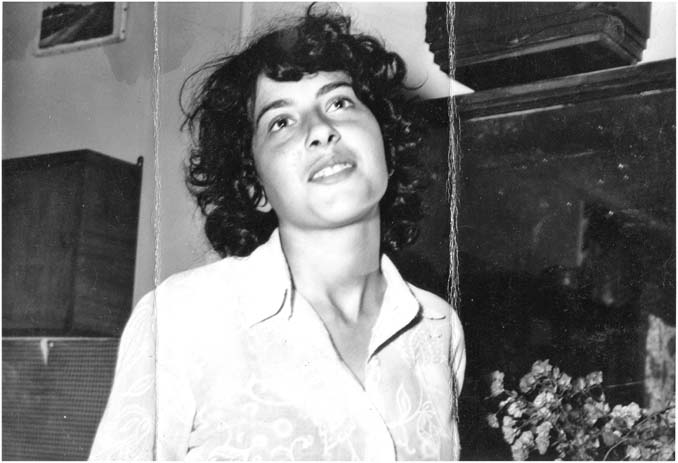

FIGURE 27. Charleen Swansea and Ross McElwee in the early 1990s. Courtesy Ross McElwee.

In the sequence in her home, Swansea’s lying across her couch, her melodramatic assessment of her embarrassing situation, and her final attempt to put a positive face on the situation come across as instances of Swansea’s typical candidness, but also as a kind of melodramatic comedy, even perhaps an evocation on McElwee’s part of Scarlett O’Hara’s final lines in Gone with the Wind. And this comedic edge is confirmed by Charleen’s singing with the out-of-tune piano. What is clear, especially from our perspective several decades later, is that in Charleen, McElwee had found one of his primary topics—the American South—as well as his Marlene Dietrich, an attractive, highly intelligent and accomplished natural performer, who seemed to defy the conventions of her place and time and who would continue to be a crucial figure in nearly all of McElwee’s most successful films (fig. 27).

It would be five years before McElwee would develop the more complex kind of presence that makes his later films distinctive, in the remarkable Backyard.8

FINDING A VOICE: ANN SCHAETZEL’S BREAKING AND ENTERING AND McELWEE’S BACKYARD

In the Diaries [Pincus’s Diaries] McElwee discovered the basic elements of a first-person observational cinema that he would develop further to the point of transforming the conventions of direct cinema: long-term solo filming; observation of one’s familiars; presence of the filmmaker behind and in front of the camera (he becomes not only a character apart, but he also created a genuine cinematographic persona, a Keaton-like screen double); confessional monologues addressed to the camera (abandoned in his later work); and, most importantly, a subjective and partial commentary in the first person.

DOMINIQUE BLUHER, “ROSS MCELWEE’S VOICE”9

For most of those filmmakers who were excited about the potential of observational cinema, one of the advantages of the new options afforded by sync-sound, on-the-spot filmmaking was the chance to avoid the forms of narration that had come to seem inevitable in documentary filmmaking. Both Ricky Leacock and Ed Pincus avoided narration, as did Alfred Guzzetti. By the end of the 1980s, however, filmmakers working in personal documentary were exploring the possibilities of new forms of narration: not the voice-of-god expert narrator so common in informational documentary, and still quite common today (in nature documentary, for example), but voice-over narration by the filmmaker, commenting on the personal activities represented in the sync-sound imagery. McElwee has become the most famous and the most adept filmmaker with this kind of voice-over, at least within the history of personal documentary—within the more general annals of personal filmmaking, Jonas Mekas’s voice-overs in such films as Walden (1969) and Lost Lost Lost (1976) are also remarkable and memorable. But McElwee’s first major experiment with this form of narration, Backyard (1984) was preceded by Ann Schaetzel’s Breaking and Entering, which was made at the MIT Film Section and finished in 1980.10

Schaetzel’s voice-over carries Breaking and Entering; without it, the imagery would have little impact. Her narration is sporadic through most of the film, but her opening comment—heard over a sync-sound, first-person shot made by Schaetzel on an airplane—frames the entire film: “I’ve come home in a state of anger. I came back to hurt my parents; I came back to hurt them because they hurt me. It’s really that simple.” Her comments are presented in a quiet, intimate voice, as if she is speaking to a friend. This opening is followed by a brief shot of her arrival at the airport gate, where her smiling father approaches her and apparently hugs her while she is filming: he seems to have no consciousness of his daughter’s anger.11 In fact, at no point in Breaking and Entering is Schaetzel’s anger ever evident to her mother and father (or to her sister and her husband). We are the only ones within the context of the film who know that more is involved here than a family visit.

Schaetzel’s anger is a result of events that took place when she was sixteen and seventeen—that is, fourteen years before this visit to her parents and sixteen years before the release of Breaking and Entering.12 Early in the film, she mentions that when her father found out she had made love when she was seventeen, he was furious, and “he threatened to kill Bob. Later he modified it and was only going to charge him with statutory rape”—the end of this voice-over coincides with her father’s saying, apropos of an entirely different subject, “I just have a continual feeling that there’s a conspiracy to make life difficult.” Schaetzel does not reveal the full story of this past event until nearly the end of the film:

When I was eighteen . . . no, when I was sixteen, I met a boy who I guess he was a man then; he was twenty-one, who was very, a very sexual person. I met him on a bus because I was working during the summer at a magazine office . . . and I knew nothing, really one of the amazing things: I knew nothing about sex. My mother had told me when I was pretty young that sexual intercourse took place when a man put his penis in a woman’s bottom. I didn’t like the sound of that.

But I fell in love with this guy, I fell in love with him, passionately in love with him and my parents forbade me to see him because they, they thought he was too old. . . . So I saw him anyway, daily, for two years, and . . . on my seventeenth birthday, I made love with him for the first time, and it was from the beginning extraordinary love-making. It was simple and powerful.

My parents discovered at one point I think about the time I was seventeen-and-a-half, that I’d been seeing him and that we’d made love. And they sent me to a farm in Belgium for the summer. . . . My mother wrote me letters everyday in which she told me my deception of them was proof that I didn’t love them and that my affair with Bob was sordid.

When I went back to Washington, I couldn’t stop seeing Bob. From then on, I was terrified of sex.

The effect of this event is evident throughout Breaking and Entering, not simply in what Schaetzel says, but in the rather depressive tone of her voice and in the nature of her cinematography.

Once she has landed in Washington, D.C., where her parents live (her father worked in the State Department much of his life and at the time of the filming was a consultant for Honeywell), Schaetzel documents everyday events: her parents reading the newspaper, a dinner party with their friends, her father pontificating about this and that, a small anniversary party thrown by her sister (during which barely suppressed friction between the parents is obvious), conversations with her mother and sister, her father’s visit to the dentist, her mother’s getting dressed to go out. . . . Ann, filming, generally does not play an active role in these conversations, and while the parents seem much involved with appearance (throughout Schaetzel’s description of the incident with Bob, her mother is ironing handkerchiefs), they seem quite oblivious to Ann’s filmmaking. Though neither parent evinces the slightest discomfort in front of the camera, this seems less a form of acceptance than an implicit indication of a smug obliviousness not merely to their daughter’s real motive for recording them but to the revelatory potential of the camera and to Ann’s seriousness as a film artist.

Breaking and Entering concludes after Schaetzel’s mother leaves the house, having told her daughter, “Don’t forget to baste.” After a few brief shots of the now-quiet house, Schaetzel cuts to a close-up of a chicken roasting on a rotisserie, and the sound of the turning rotisserie continues to be audible once the screen goes dark and the credits roll. This sound has several levels of implication: the revolving chicken seems to represent the boring repetitiveness of her parents’ marriage; it suggests the way in which the parents’ intervention in Ann’s love life has continued to affect their daughter and produce the anger (the heat) that they are so oblivious to; and it confirms with subtle humor that Schaetzel’s revenge on her parents is complete: they have been “cooked” by their daughter’s filmmaking without having any sense of what their normal activities and conversations have revealed about them.

In a very real sense, Breaking and Entering is about Schaetzel’s narration. Her implicitly depressive voice-over helps us understand that Schaetzel’s thoroughly anti-romantic black-and-white cinematography is an expression of suppressed anger and depression. The film seems an instance of what Laura Mulvey once called “scorched earth filmmaking”: that is, feminist filmmaking that “consciously denied spectators the usual pleasures of cinema.”13 Breaking and Entering shares an implicitly grim, shell-shocked mood with Su Friedrich’s films up through Gently Down the Stream (1981) and with Sally Potter’s Thriller (1979).

McElwee’s Backyard, finished four years after Breaking and Entering, depicts another trip home by a filmmaker who feels alienated from his family, and it expands on the narrative strategy developed by Schaetzel. After handwritten credits, Backyard begins with a brief précis, spoken by McElwee and illustrated by a series of three still photographs of his father and himself, camera in hand (each photograph separated from the next by one second of darkness):

[first photograph: long shot of the father and son in the McElwee backyard in Charlotte, North Carolina]

Before this film begins, I have to tell a story about my father and me.

When I was eighteen, I left my home in North Carolina to go to college in New England, and ended up living in Boston. Ever since then, my father, who was born and raised in the South, and I have disagreed about nearly everything.

[cut to second photograph: McElwee and father in medium shot, looking at each other]

When I graduated from college, my father, who’s a doctor and conservative Republican, asked me what I planned to do with my life. I told him I was interested in filmmaking, but that there were also several other alternatives, such as working with black voter registration in the South, or getting involved in the peace movement, or possibly entering a Theravadan Buddhist monastery.

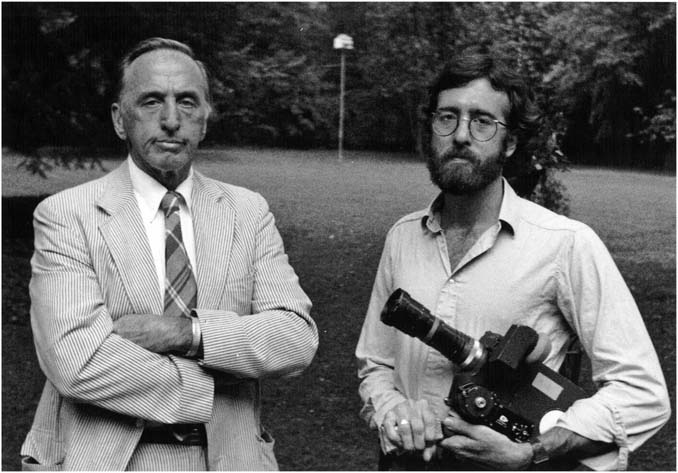

FIGURE 28. The third photograph of Dr. McElwee and Ross McElwee from the opening précis of Ross McElwee's Backyard (1984). Courtesy Ross McElwee.

My father thought this over for a moment and said, “Son, I think your concept of career planning leaves something to be desired. But I’ve decided not to worry about you anymore. I’ve resigned myself to your fate.”

[cut to third photograph (fig. 28): the McElwees in medium shot, but closer to the camera than in the previous image, looking at the camera]

I didn’t know exactly how to respond to this, but finally I said, “Well, Dad, I guess I have no choice but to accept your resignation.”

This opening sequence reveals several major changes in McElwee’s approach to documentary and several distinctions from Schaetzel’s approach in Breaking and Entering. For one thing, McElwee makes it immediately clear that this voice-over means to do more than provide contextualizing information about the action within the film. This voice-over posits a relationship between the filmmaker and the viewer that supersedes the film itself (“Before this film begins . . .”). Further, it seems evident in McElwee’s monologue that he has carefully written and practiced speaking his comments; McElwee’s pun on “resignation” feels more literary than anything in his previous films, and his delivery is carefully modulated: when he recalls what his father said to him, he subtly imitates his father’s speech. This commentary is not in service of the visuals, but vice versa; the use of the three photographs is clearly (and humorously) illustrative of what McElwee says, and the changes from one photograph to the next provide a subtle and witty punctuation for the monologue. Further, McElwee’s review of his “other alternatives” not only demonstrates a youthful rebellion against Dr. McElwee and what he represents, it suggests that McElwee can be the butt of his own humor: his listing of alternatives seems amusingly typical of the often self-righteous pretension of youth—pretension that, judging from the fact that we are watching a finished film, seems, even to McElwee in the “present” of the voice-over, a thing of the past.

The most obvious change in approach, of course, is the humor of this précis, humor evident not only in what McElwee says and in his delivery of the monologue but in the way in which the three photographs reveal the two men. McElwee’s father is dressed in a suit and tie, arms folded over his chest, while McElwee is casually dressed and holding his camera, which is pointed at his father as if it were a gun. The wry humor of the précis is confirmed in the opening sequence of the film proper, when McElwee himself is seen playing the beginning of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” on the family piano (playing badly, on a piano that is out of tune); in voice-over he indicates that the one thing his father and he do agree on is the unlikelihood of Ross’s having a musical career.

McElwee cuts directly from the piano playing to a hospital operating room where his surgeon father is cutting off a growth, and McElwee’s voice-over comments, “In the past I’ve felt queasy when I’ve seen my father’s scalpel cut through warm living flesh, but I discovered that, as long as I was filming my father operating, this problem disappeared completely.” He adds, “Unfortunately, I had other problems,” just before his camera malfunctions—the conceit is that his father’s presence has the power, or more precisely used to have the power (the voice-over implicitly postdates the shooting), to interfere with McElwee’s equipment. The film’s third sequence is also comic: McElwee films his stepmother Ann and his father, sporting a yarmulke, listening to a couple singing “Silent Night” to them on the phone, a ritual that “occurs every Christmas.” “For some reason,” McElwee comments, again in voice-over, “my father is wearing a yarmulka, despite the fact that he’s a staunch Presbyterian.”

While Backyard begins with repeated instances of McElwee’s deadpan humor, it is soon clear that the film is about a good deal more than family foibles and a son’s oedipal struggle with his father. During the first piano-playing shot (he returns to this shot twice during the first half of Backyard), McElwee indicates that he had come home “to make a film about the South, which for me meant making a film about my family.” That this is the second mention of the South as a region (the first is Ross’s apparent interest in working with black voter registration), and that it is followed by his introduction of Melvin and Lucille Stafford, African Americans who have worked for the McElwee family since Ross was a child (“As I grew up, I never questioned the fact that black men were taking care of the yard, while their wives were taking care of me”), makes clear that Backyard is about the specific issue of race in the South. If, growing up, he never questioned the fact that blacks helped his family to function, McElwee is certainly questioning this now—or at least using the making of this film to see the reality more clearly than he could as a child.

As McElwee is introducing the Staffords in his voice-over, Melvin Stafford is seen raking leaves, with neighboring dogs barking at him, and McElwee asks whether the dogs always act this way. Melvin says yes and evinces surprise that the dogs never seem to get used to him, before McElwee moves in for a closer shot of the dogs, barely visible through the brush that separates the two yards. Within the context McElwee has created, the implicit evocation of slavery is obvious. Then, we see Lucille Stafford working in the kitchen, asking Ross if he wants some soup, as McElwee’s brother Tom and his friends come in and leave the kitchen (Tom hugs and kisses Lucille). After further shots of Lucille and Melvin Stafford working (Melvin and Ross also discuss Ross’s childhood treehouse), McElwee concludes the sequence with the third shot of him playing the piano: the awkwardness of his playing on the out-of-tune piano now suggests McElwee’s discomfort with his recognition that while the McElwees and the Staffords seem very comfortable, even affectionate, with one another, their relationship is nevertheless an instance of the history of the problematic racial politics of the South and the resulting economic disparity between the two “races.”

During the remainder of Backyard McElwee confirms his awareness of some of the obvious and subtle ways in which racial history has affected the present-day South, and he does this within a particular cine-historical context. By the early 1970s, film scholars were beginning to explore the representation of African American characters in American cinema and to recognize that a relatively predictable set of stereotypes accounted for most roles African Americans had played in commercial films. The first edition of Donald Bogle’s Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks appeared in 1973 and, with its provocative title, established what Bogle, and most scholars after him, understood as the most prevalent stereotypical film roles available to African American actors.14 Two of these stereotypical figures, the tom and the mammy (and her offshoot, the aunt jemima), were conventionally depicted as loyal domestics whose lives were defined by the white families they worked for.15

It cannot have escaped McElwee as he was editing Backyard, and it does not escape those who have learned about ethnic stereotyping, that Lucille and Melvin seem, at least at first, to fit these roles. In a very general sense, Lucille and Melvin Stafford look like the mammy and the tom in D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (which of course is set in the Piedmont region of the Carolinas, where Charlotte is located); and we see them almost entirely within the context of the McElwee household (McElwee never depicts the Staffords in their own home—though he does visit the backyard of Clyde Cathey, a beekeeper who does yard work for the McElwees and their neighbors, and he goes with the Staffords to visit Lucille’s hospitalized brother).16 Further, even though it is obvious that the McElwees are financially well off—they live in an elegant neighborhood, near a country club—Melvin must struggle to start the McElwee’s old lawnmower but doesn’t offer the slightest complaint about this.

Of course, although McElwee’s depictions of the Staffords evoke two of the stereotypes Bogle defined, the Staffords are not actors playing scripted stereotypical roles in a fiction film. They are individuals who are documented doing their jobs and living their very real lives. They are, of course, instances of the southern class system, the twentieth-century inheritance of the history of slavery, but they are neither caricatures nor sociological data; they are living individuals not only in McElwee’s film but in his life. The stereotypes defined by Bogle are normally understood within the history of the representation of blacks in literature and the visual arts, but they must also be understood as exaggerations of particular social roles that real African Americans have played in southern society: while many African Americans have in fact worked as domestics and as domestic laborers in and around white southern homes, and may have acted or even felt grateful to have these jobs, for viewers to conflate Hollywood stereotypes with real individuals, that is, to understand the Staffords merely through the lens that Bogle and other scholars of African Americans in cinema have provided, is to reduce the Staffords to caricatures and to participate in precisely the kind of reductive thinking that produced these racist stereotypes in first place.

Within Backyard the most obvious distinction between whites and blacks, other than the differences in social class, is the way in which the two groups react to McElwee’s filming. It is evident from the beginning of the film that Dr. McElwee is dubious about his son’s involvement in filmmaking and is uncomfortable in front of the camera (though it must be said that he does give his son entry to the operating room and allows Ross to join him in visits to recovering patients). At one point, he looks at the camera and says, “I’ll be glad when that big eye’s gone.” In another instance, as he is being filmed putting up a volleyball net for a party, he expresses puzzlement about what his son uses his “expensive film” to record. Even at the end of the film, McElwee follows his voice-over explanation that he and his father are “getting along pretty well these days” with a final instance of his camera jamming in the operating room—confirming the earlier suggestion that his father’s proximity (and implicit hostility to his son’s career choice) causes his equipment to malfunction. Tom McElwee is also uncomfortable around the camera and hides behind a newspaper when Ross is filming him at the breakfast table. And when McElwee visits the country club kitchen, the (white) man in charge (most of the other employees in the kitchen are black) asks, with a wry, uncomfortable smile, whether McElwee is filming “all the dirt here.”17

McElwee’s stepmother and grandmother do seem supportive of his filmmaking. McElwee tells us that during his visit Ann suggested various activities for him to film and that his grandmother offered to sing some old songs for the camera, but in general McElwee indicates that “I had many contradictory feelings about being home again, and I felt very awkward about filming members of my family.” These contradictory feelings are certainly confirmed when his grandmother sings for him and he mentions that he “was especially struck by the lyrics to one of her songs”:

Lilac trees are blooming in the corner by the gate,

Mammy in her little cabin door,

Curly headed pickaninny coming home from school

Just crying ’cause his little heart was sore.

All the children round about have skin so white and fair

None of them with him will ever play,

But mammy in her lap takes this dusty little chap

And she croons in her own kind way:

“Now honey, don’t you mind what them white childs do,

And honey, don’t you cry so hard.

Go out and play as much as you please,

But stay in your own backyard.”

McElwee was struck enough to use the lyrics as the source of his title, and I would guess that most viewers are struck by this elderly woman’s apparent obliviousness about the implications of the lyrics she sings so beautifully. Her smile when she finishes the song is both endearing and a vestige of the South’s troubling past, as is suggested by the faded quality of this imagery.18 However, even if we think of the way of life emblemized by the song as fading, the lyrics come through loud and clear and continue to have more relevance in McElwee’s life, and in ours, than we might wish.

Generally, the African Americans filmed by McElwee betray little discomfort with his camera. Melvin and Clyde seem completely at ease with McElwee’s filming, and Clyde is happy to recall stories about his beekeeping. When Ross is filming Tom McElwee in the kitchen, hiding behind the newspaper, Tom asks, “You like the camera, Lucille?” And Lucille responds, “It don’t bother me.” Indeed, Lucille seems to accept that filmmaking is part of Ross; she laughs the first time she sees Ross filming her, but she goes about her business, asking him if he needs anything, even as he films. Early in the film, McElwee explains that his mother “died the year before I moved to Boston; my father has since remarried,” and even if Ross gets along with Ann she seems to be something of a stranger to him, as in fact are his father and brother: early in the film McElwee explains that “since moving away, I felt I’d become a kind of stranger to my own family. My brother had even taken to calling me ‘the Yankee.’” If his family considers him a stranger, however, there is no evidence in the film that Melvin and Lucille feel this way. Early in Backyard, we see Lucille Stafford transferring boxed shoes to a bag, and in voice-over McElwee comments, “Lucille was given the last of the clothing that belonged to my mother.” I read this moment as a suggestion that McElwee sees Lucille not exactly as a replacement for his mother but as what she has always been: one of the women who has helped raise him, and someone who continues to support the person (and the filmmaker) he has become.

An exception to the pattern I’ve described occurs when McElwee joins Lucille and Melvin when they visit Lucille’s brother in the hospital. On one level, this suggests that McElwee feels himself a part of the Stafford family, though in the hospital sequence it seems clear not only that Lucille Stafford’s brother is uncomfortable with Lucille and Melvin but also with McElwee’s camera. After Lucille and Melvin leave the room, McElwee remains for a moment filming, and the brother’s discomfort with his presence becomes obvious. As McElwee later explained:

He makes a gesture, a sideways move of the hand that’s right on the border between being a wave, a perfectly innocent good-bye, and a somewhat hostile shooing me away. This man is very depressed, and a lot of the reason he’s depressed is because he’s oppressed. For whatever reason (I don’t know the specifics of his history), his alcoholism, growing up black in the South, never having had anything of material value, starving himself—that’s what Lucille said; he’s suffering from malnutrition—that gesture is very important; it’s emblematic of an anger that blacks in the South want to express, but can’t really because of the mutual interdependency between blacks and whites, and because of an odd sense of family. And I don’t mean “family” in a sentimental way: it’s not a good situation. . . . Certainly there’s the implication in that scene of the cameraman as one more white exploiter of the black class. I am victimizing the helpless, using them for fodder for my film. If I’d cut the shot before the gesture, I would have cleaned the scene up as far as implicating myself in this idea of white domination of blacks. But then it would have been dishonest. Godard’s comment about every cut being political is very true.19

The conclusion of Backyard reconfirms McElwee’s nuanced exploration of the issue of race in his own backyard. First, he returns to his father in an operating room visually, as his voice-over defines the temporal distance between the footage we’ve been looking at during the film and his commentary about it: he mentions that he goes down to visit his father whenever he can, “and I continue to make films. My brother is now a surgeon and Lucille continues to keep the house in order while Melvin keeps mowing the lawn. And basically, things go along smoothly, pretty much the way they always have.” Immediately after this voice-over concludes, McElwee’s camera malfunctions as his father passes near it, and the last we see of the hospital is a brief blurry image of a black orderly leaving the operating room. Things may seem to be moving smoothly, but clearly the tensions that McElwee experienced during the time when he was shooting are still in evidence.

Of course, “smoothly” for whites is different than it is for blacks: Tom McElwee has become a surgeon and Ross an accomplished filmmaker, so accomplished that he can use those moments when his camera malfunctioned as humor within the accomplished film we’ve been watching. But Lucille and Melvin have gone nowhere. During the film’s final shot we see, from inside the McElwee home, a window that looks out onto the backyard, as Melvin, on the old McElwee lawnmower, rides by. McElwee’s composition of the small window inside his film frame suggests the constrictions of black life in the South, even within households like his own; and the fact that we see Melvin through the metal grid of the window guard suggests that, for all his family’s good will toward the Staffords and African Americans in general (MCELWEE: “I’m told that when my father set up his practice in Charlotte . . . he was the first doctor in the city to have a desegregated waiting room”),20 life in the McElwee backyard remains a kind of prison for them.

DOPPLEGÄNGER: SHERMAN’S MARCH

He said, “You can’t be in love and be in this business.”

UNNAMED FILM DIRECTOR, AS REPORTED BY PAT RENDLEMAN21

In his canonical meta–short story, “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” Ernest Hemingway uses an unusual narrative strategy.22 “Snows” charts the demise of Harry, a writer whose African hunting safari has been interrupted by a serious infection that has developed from an untreated scratch; as he lies in his tent on an African plain, he is dying of gangrene. As Harry drifts in and out of consciousness, he remembers a series of events that he had never gotten around to writing about, and he realizes that he has failed as a writer because he has allowed himself to become distracted (by wealth and fame) from doing justice to his gifts. Of course, most readers of “Snows” will remember that Hemingway himself was a devotee of hunting in Africa, and a good many of those who have written about the story have drawn comparisons between Harry and Hemingway. What is unusual about the story’s narrative strategy, however, is the way in which it offers Harry as an example of literary creativity gone awry within a story that demonstrates its author’s literary creativity going full bore. Hemingway uses italics to present the various events that Harry feels he should have written about, not so much as a way of calling attention to these events as memories (other memories, memories implicitly not worthy of becoming literature, are not italicized), but rather calling attention to the fact that while Harry did not write about these events, Hemingway did; indeed, for anyone familiar with Hemingway’s career, the italicized passages in “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” evoke the italicized chapters that separate the longer stories in his first important book, In Our Time (1925). As Hemingway said in Green Hills of Africa (1935), the nonfiction account of his own 1933 safari, “The hardest thing” for a writer, “because time is so short, is for him to survive and get his work done.”23 In “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” Hemingway uses Harry to dramatize the dangers that time can pose and demonstrates, through his completion of “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” that it is possible to resist the moral and aesthetic corruption that destroys Harry’s career. Harry is the writer Hemingway might have become but has not.

In Sherman’s March: A Meditation on the Possibility of Romantic Love in the South during an Era of Nuclear Weapons Proliferation (1985), McElwee uses a similar strategy, but for a documentary comedy. He creates a Ross McElwee character, a character obviously based on his own experiences, who seemingly fails to achieve his goals, but within a film in which McElwee demonstrates, as director, that this Ross McElwee character is not the only Ross McElwee we need consider. McElwee’s double presence as director and character is set up as the film begins. First, we see a map of the American South and hear what seems to be a traditional voice-of-god narrator who provides a brief description of Sherman’s “march to the sea” during 1864, leaving “a path of destruction sixty miles wide and seven-hundred miles long.” That some aficionados of documentary will immediately recognize that this is Ricky Leacock’s voice provides an in-joke: Leacock, as McElwee has explained, “pioneered a kind of filmmaking in which narration, didactic narration at any rate, was to avoided at all costs.”24

At the conclusion of Leacock’s opening narration, we hear McElwee himself ask Leacock, “Do you want to do it once more?,” and Leacock’s response: “Do it again. Yes.” This has a variety of effects. First, it reveals that the supposedly disembodied, voice-of-god narrator is in fact an actor, performing the role of expert; and second, it makes clear that McElwee is in charge of this process. As a result, when McElwee subsequently begins his own narration, with “Two years ago, I was about to shoot a documentary film on the lingering effects of Sherman’s march on the South,” we understand both that this is the voice of the film’s director and that, like the immediately previous Leacock narration, this one is a performance by an actor (McElwee himself) who is implicitly directed. That this is the case is evident in McElwee’s suggestion that he was working on a documentary on Sherman “two years ago.” At first we may understand the Leacock narration (and the map and photographs that follow it) as vestiges of this earlier project,25 but even as we imagine that this is the case, we cannot not realize that, whenever this material was recorded, it has become the beginning of the film we are watching. The fundamental reality of Sherman’s March, of course, is that the film that begins to unfold (or has already begun to unfold) as the McElwee character heads South to see his family “to try and begin my film” has already been completed by McElwee, the director. Clearly, whatever frustrations and failures McElwee will be documenting have been recycled into the completed film we are watching (McElwee’s indication that he has gotten a grant to make his film confirms these implications; obviously not everyone is successful in getting financial support from grant agencies).

In his opening narration McElwee explains that the woman he’d been seeing has decided to go back to her former boyfriend and that he is staying in a friend’s currently vacant studio loft, as he is seen in extreme long shot in an empty New York loft, first pacing back and forth in front of very large windows, then sweeping up, then looking into what appears to be an empty refrigerator. This moment provides deadpan humor, in part because it is obvious that McElwee has either directed someone else to film him or he has somehow figured out a way to film himself in long shot as he reenacts activities that he may have originally performed when he came into this loft or, more likely, that he has decided will be adequate to evoke whatever that original experience was. Already, McElwee is present in this scene not only as an actor, and as the person telling us about his situation, but as the person who set up this amusing composition (McElwee seems tiny in this huge space, as “tiny” as his character supposedly feels) and as the director who, much more recently, has edited the film we are watching so that we hear his character’s comments as we watch him. This prelude to the body of Sherman’s March—the title and director credits appear immediately after McElwee’s first voice-over concludes—has much the same function as the prelude to Backyard. In both cases, McElwee’s introduction of himself creates a larger (implicitly directorial) context for the actions of McElwee as character.26

In the sequence that follows the opening credits, McElwee develops both his McElwee character and our consciousness of him as director, confirming the comic mood evident in the scene in the New York loft—and beginning the articulation of the complex approach that made Sherman’s March a breakthrough not only for McElwee but for autobiographical filmmaking. In voice-over McElwee introduces us to his family as they walk through the woods to attend a picnic and Scottish festival at a resort. McElwee films his sister and brother, then his father, and sets up the basis for the action that follows in a voice-over: “For a long time, the consensus among family members is that what I really need to do is find what they call ‘a nice southern girl’. . . . They’re on vacation in the mountains of North Carolina and they’ve invited me to go with them to a picnic and festival. They’ve also invited a number of family friends and their sons and daughters—mostly, it seems, daughters.” This voice-over, like the earlier one, has a doubling effect, first, because McElwee refers to his family as “they,” even though he is with them on this vacation (he could of course have said, “We are on vacation”—though, as a filmmaker Ross is not); but also because the voice-over is superimposed with McElwee’s sync–sound recording of the family walking through the woods: we hear his voice-over just after he says, “Hi, sis!,” and “Where’s dad? Oh, he’s way back there.” That is, McElwee is present simultaneously as a character within the action and as a commentator on the action.

Further, as Dominique Bluher has said, this and subsequent voice-overs add a doubling effect as a result of McElwee’s unusual use of the present tense: “Whereas McElwee writes and records the commentary during editing . . . the commentary is written in the present tense”—what Bluher calls a “past-present”: “More shrewdly, the manner of dating or using temporal deixis, creates an effect of coexistence, as if he were commenting on the images for viewers during the projection of the film in a movie theater. . . . In this manner, three presents superimpose themselves one on top of the other: the past-present (images), the present-present (speech utterance), and the future-present (projection); or, from another perspective, two pasts (shooting and the recording of voice-over) actualize themselves in each new projection.”27 I would add an additional “present”: the present when McElwee brought the images and the speech utterances together in the editing. Precisely at the statement, “mostly, it seems, daughters,” McElwee cuts to a line of young women walking through the woods, which is amusing because of McElwee’s precise timing. If, on one hand, we see McElwee, within the present of the film’s action, somewhat at the mercy of his family, the obvious wit of his cut to the young women filing past his camera is evidence of his total directorial control over what we are seeing and hearing.

The deadpan survey of the almost ludicrously phallic Scottish games, “various demonstrations of strength and virility,” that follows at the picnic seems to confirm the idea that McElwee himself is not strong or virile. But again, regardless of the self-effacement he performs in the action or draws our attention to in his voice-overs, it is clear that ultimately McElwee is in complete control of what we are seeing and how we are seeing it. This simultaneous development of the McElwee character as a bit of a sad sack about whom his family is concerned and of McElwee’s considerable wit as director continues throughout Sherman’s March and evokes a certain tendency in 1920s American film comedy, and in particular—as Bluher has suggested—Buster Keaton, who, like McElwee, often played self-effacing roles within films over which he had virtually total directorial control. The embarrassments and dangers Johnny Gray experiences in The General (1926), for example, are funny because, and only because, we understand that Buster Keaton created these experiences for the character he plays and that he survived his dangerous stunts and completed this remarkable film.

During the sequence after the Scottish games, McElwee takes advice about his love life from his sister Dede and subsequently attends a fashion show with his stepmother Ann, where one of the women modeling clothing is “a childhood sweetheart of mine, someone I haven’t seen in over twenty years.” These two events introduce another subtle but crucial aspect of McElwee’s approach. The conversation with Dede takes place in a canoe, as Dede paddles while making suggestions about how McElwee might “tidy up” and dress more carefully to attract women. Dede wears sunglasses so that it is difficult to see precisely where she is looking, and we understand the conversation as Dede talking with McElwee-as-the-camera. However, during the next two conversations—the first with his stepmother Ann; the second, with Mary, the childhood sweetheart—McElwee is holding the camera so that it is to the right (and slightly below) where we assume his face is, so that when Ann tells McElwee that she has planned to attend the fashion show, she looks to the left of the camera, at McElwee. That is, the gaze of McElwee’s camera is quite distinct from his gaze as a character within the action. The same is true, but even more dramatically, when he meets Mary at the fashion show: Mary looks to the left of the camera at Ross, who judging from her gaze, is standing up, and the camera captures the excitement of the reunion from below. After they greet each other, Mary asks what McElwee is doing, and he responds, “I’m making a film about Sherman’s march to the sea.” Mary sees this as a joke, but they agree to meet each other later. During their subsequent conversation, the same visual situation is created: Mary talks with McElwee, looking to the left of the camera, which provides us with an oblique angle onto the interchange.

This unusual strategy has a variety of effects, the most obvious of which is to create humor through the very awkwardness of McElwee’s conducting a social interaction (including a hug at the beginning of the reunion and kiss good-bye when Mary leaves the resort) while carrying a camera and recording equipment. But there are more subtle and suggestive implications as well. That the camera literally provides an angle on these situations different from the one experienced by the McElwee character confirms the doubling effect evident in other ways earlier in the film: there is McElwee the character and McElwee the filmmaker—a filmmaker who knows as he is shooting that, whatever else is going on, he is in the process of making a film. That is, McElwee is automatically somewhat detached from the emotional involvements that his character seems to be experiencing. The separation of the McElwee character’s gaze from the gaze of McElwee’s camera remains obvious in nearly every important interchange in Sherman’s March, and the few exceptions to this pattern prove the rule. Of course, many filmmakers who have filmed within events have carried their cameras on their right shoulders, and during interviews their subjects have looked slightly to the left of the camera’s gaze. McElwee’s distinctive exploitation of this device, however, gives it a complex psychological dimension.

McElwee’s use of the split gaze confirms the implicit doubling evident in the voice-overs, when McElwee seems to be speaking to us even while he is engaged in the film’s action. While we understand that it is McElwee’s camera that is viewing his conversations from a different angle than he himself has, the effect is that we seem to be present at these events, experiencing them from the camera’s position. Like his speaking to us in voice-over, this positioning of the camera creates the sense that we are McElwee’s confidants (as we are Schaetzel’s confidants in Breaking and Entering), intimates who are present during his experiences, and in many cases, closer to him, both physically and emotionally, and often politically, than those we see him speaking with. This becomes particularly evident during McElwee’s subsequent interactions with Pat Rendleman and Dede’s friend Claudia, the next two women McElwee meets on his march through the South.

This sense of the two Ross McElwees and the film’s positioning of the viewer as director McElwee’s confidant and partner are confirmed during several extended monologues that McElwee delivers to the camera in voice-over and in person. After Pat Rendleman leaves for Hollywood, McElwee, lying in a motel room bed, complains to the camera about his situation(“Having two large empty beds is twice as depressing as having one large empty bed”) then, as we see a shot of the moon, he remembers his experience in Hawaii as a child, when he and his family saw the white flash of the Crossroads nuclear test from eight hundred miles away: “We could see the ocean sparkling for miles out on the horizon, and behind us, Honolulu was as visible as if it were broad daylight. This flash gave way to a lingering lime green which then faded to a sort of deep dark red, and then finally, the stars and moon started to come back out through the redness. No one on the beach said anything.” The bedroom scene, of course, presents the sad sack McElwee, but the memory of the nuclear flash functions on a different register: McElwee’s elegant, sobering description suggests the immensity of the Crossroads test; whatever humor is created by his bedroom scene complaint is overshadowed by this memory, and it sets the stage for his complex response to events that occur later in Sherman’s March.

McElwee’s most memorable on-screen monologue occurs the night after a costume party McElwee attends with Claudia and her daughter Ashley. Dressed as a Union officer, McElwee talks about the good time he had at the party, then provides some history of Sherman, revealing the complexity of the general’s feelings about the South (he had lived in the South before the Civil War, then at the end of his campaign offered the South very generous terms at the surrender).28 At the beginning of the monologue, McElwee says, “I have to be quiet . . . because my father is asleep upstairs, and I think he already has enough questions about the validity of my film project without seeing me dressed up like this, talking to my own camera, so I have to be quiet.” McElwee repeatedly looks over his shoulder while he is speaking to the camera, as if afraid of being interrupted, and the effect is that we seem to be taking part in a secret conversation with him. Within the action of the film, he is speaking to the camera, but within the larger context of the finished film, he is in fact speaking to those of us who are watching this scene: even as he plays the role of the nervous son, McElwee is fully aware that he is speaking not just within the present but to the future viewers of the film he is directing.

McElwee’s development of a complex relationship with the viewer occurs just as his tour of the South in search of love (and for the remnants of Sherman’s military campaign) is getting underway. The first potential girlfriend is Pat Rendleman, whose narcissism and apparent inability to imagine how she might appear to those who will watch McElwee’s film make her a comic character. Rendleman’s performing her cellulite exercises for the camera (and saying that “I’d do them a lot better if I had on some underpants”) keeps the McElwee character awake that evening (“I keep wondering how I should have responded to Pat’s comment about not wearing any underpants; I mean, that’s not like telling someone that you’re not wearing any socks”), and provides the Sherman’s March audience with laugh-out-loud humor. Rendleman’s remarkable ability to make a fool of herself on camera is confirmed when she describes the screenplay she plans to write: in the movie she imagines, she becomes the best actress in the world in a love scene “comparable to Romeo and Juliet”; she moves to a South Seas island where she founds a think tank and cures cancer, and when her jealous “Tarzan-lover” beheads her, her head arrives in Hollywood to address the planet. The doubling of McElwee as actor and director is nowhere more obvious than during the Rendleman sequences. As a character, McElwee pretends to be fascinated, even infatuated with Pat—and while this may be the case, it is only in the sense that Rendleman is the perfect subject for the comedy McElwee the director is making. As inventive as McElwee is as a writer (his voice-overs are consistently witty, intelligent, and carefully researched), he could never have written the lines that Pat Rendleman provides him with. It is a tribute to his abilities as an actor, in fact, that he can listen, seemingly with serious interest, to Pat’s description of her screenplay and stay engaged with her as she subsequently pursues her career in Atlanta and leaves for Los Angeles.

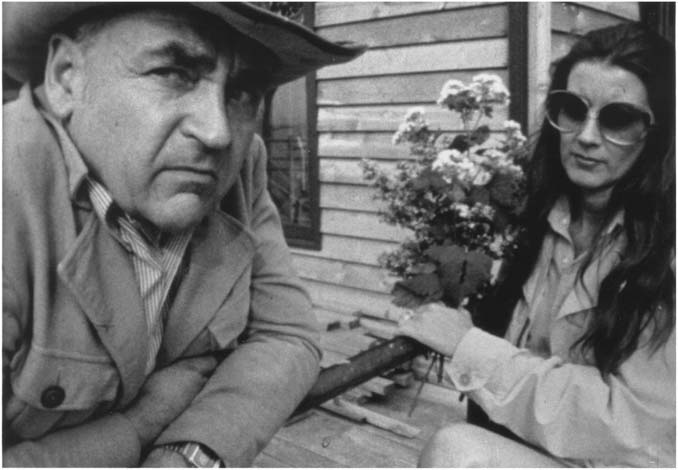

McElwee’s interactions with Claudia and her daughter Ashley are not material for the kind of humor that Rendleman creates, but the people Claudia introduces him to (an evangelist who sees the coming destruction of the planet as a temporary stage on the way to the Second Coming and several survivalists who are in the process of setting up a compound in the mountains where they’ll be able to weather a nuclear holocaust—it includes a tennis court) are material for grim amusement (fig. 29). Again, the McElwee character pretends interest in what these men (and Claudia herself, who provides McElwee with a tour of her fallout shelter) believe, in the service of director McElwee’s determination to make these people part of his portrait of the modern South. The description of the Crossroads test that precedes McElwee’s visits to Claudia suggests the immense scope of even a single nuclear detonation, rendering these survival plans as childish as Ashley’s dollhouse. During Sherman’s March, McElwee’s creation of his often diffident character is more than a means for creating humor; it allows him to function as a kind of spy within what would otherwise be hostile territory for a northern intellectual. Obviously, it would be something of a stretch to call Sherman’s March an ethnographic film, and yet, McElwee’s lovelorn character is in large part a disguise that allows him to create a memorable and intimate panorama of a region of the country and the people who live there that can seem as surreal as the worlds we visit in Robert Gardner’s Dead Birds and Deep Hearts.

FIGURE 29. Claudia’s survivalist friend speaks with McElwee as he films, in Ross McElwee’s Sherman’s March (1986). Courtesy Ross McElwee.

During the remainder of Sherman’s March, McElwee’s interactions with southern women vary a good deal, both in terms of his feelings for these women and in the ways in which the film depicts these relationships. None of the young women we meet after Pat Rendelman is absurdly comic in the way Rendleman is, and in certain instances McElwee does in fact develop feelings, or revisits earlier feelings, for these women. His visit to Winnie on Ossabaw Island, for example, is full of humor, but not at her expense. Unlike the other women McElwee has met, Winnie is an intellectual, a linguist working on her Ph.D. When McElwee asks her to discuss her work on camera, she responds, “I can’t explain the theory of linguistics in two and a half minutes; that’s ridiculous!” But she and McElwee talk at some length about linguistic concepts (a series of jump cuts humorously suggests both Winnie’s willingness to talk at length about her work and McElwee’s growing interest in Winnie), leading to his asking her how it is that she always got involved with her instructors and professors. Winnie, embarrassed, replies, “You’re really fascinated by someone who can talk well and think well about the things that you find most interesting. For a very long time I thought the most important things in life were linguistics and sex. It’s easy to see how one would get involved with a linguistics professor.” McElwee moves in for an extended stay, and soon is describing to Winnie his own research on Sherman, which Winnie engages, just as he has engaged her linguistics research. Not surprisingly, McElwee soon feels that he’s “stumbled into Eden.”

During McElwee’s conversations with Winnie, his camera doesn’t take a separate angle from the McElwee character.29 Here, character and director merge, and a real relationship is formed. We learn later—when McElwee returns to Ossabaw Island after an extended stay in Boston where he has taken an editing job—that Winnie has moved on from the sexual relationship they had been sharing by the end of his first visit. In other words, even when McElwee has achieved a relationship, his commitments as a filmmaker have taken precedence.

McElwee next visits ex-girlfriend Jackie. Like Winnie, Jackie is not material for McElwee’s humor, in part because her commitment to antinuclear work seems a more sensible response to the threat of nuclear war than building fallout shelters or mountain hideouts and also because she is clearly a committed and energetic art teacher at a public school in Hartsville, South Carolina, where her students seem to be primarily African American. Jackie is reluctant to talk with McElwee about whatever their former relationship has, or has not, meant to her, and when they do have a moment alone together, it is clear that Jackie is in no particular hurry to fall in love: “I think it’s all more trouble than it’s worth.” When McElwee suggests that she’s “become cynical in her middle age,” Jackie replies, “Yeah, haven’t you?” If Jackie is more fully involved in her political concerns and her teaching, and in her plans to move to California, than with her love life, McElwee is more fully involved with his filmmaking than with searching for a mate, even when he pretends that he is searching, which is, in fact, not far from cynicism.30

After a brief interlude when McElwee talks with a would-be Burt Reynolds stand-in and a visit to a historical exhibit that emphasizes that the Civil War was a testing time for a breed of new and deadly weapons, McElwee travels to Charleston, South Carolina where he reunites with Charleen Swansea, who professes to be bored with his “singleness” and advises him to “forget the fucking film and listen to DeeDee,” a young woman she believes is the perfect partner for him. The meeting with DeeDee reestablishes the split gaze situation, and Swansea speaks probably the most memorable, and most ironic, line in the film. “Would you stop!,” she says to McElwee, and covers the camera lens with her hand; when McElwee says, “Don’t touch that lens!,” she replies, “I can’t help but touch it. This is important. This is not art, this is life!” A moment later, when McElwee films Swansea explaining to DeeDee that McElwee is no longer filming, just turning the camera from one person to another, Swansea’s delusion about what is happening is underlined: in fact, this meeting with DeeDee is, at least for McElwee, art, not life, something that DeeDee may understand more fully than Swansea does.

Throughout this visit to Charleston, the potential relationship with DeeDee seems less McElwee’s focus—both McElwee and DeeDee are humoring Swansea—than Swansea herself. Swansea’s considerable accomplishments as an intellectual and as a teacher, so obvious in Charleen, are invisible in Sherman’s March. Indeed, here, Swansea plays a role closer to Pat Rendleman. Further, unlike Winnie, Swansea seems not only disrespectful of McElwee’s filmmaking, but uninterested in his research on Sherman, even when McElwee tells her that Sherman “painted portraits of his friends in Charleston; he did still-life watercolors of the landscape”—clearly one of the aspects of Sherman that McElwee relates to: he too is creating portraits of people and landscape imagery of the South. What seems implicit throughout the Charleston visit becomes clear when DeeDee and McElwee talk about her commitments as a Mormon and her desire “to bring the priesthood into her home.”31 The Charleston visit ends when Swansea announces she has found still another perfect woman for McElwee, and filmmaker McElwee conveniently runs out of film: what appears to be end-leader creates a kind of cinematic ellipsis.

A visit to Sheldon Church, torched by Sherman’s troops in November 1964, leads to the McElwee character’s assessment of his filmmaking process: “It seems like I’m filming my life in order to have a life to film, like some primitive organism that somehow nourishes itself by devouring itself, growing as it diminishes. I ponder the possibility that Charleen is right when she says that filming is the only way I can relate to women. I’m beginning to lose touch with where I am in all of this. It’s a little like looking into a mirror and trying to see what you look like when you’re not really looking at your own reflection.” As he delivers this voice-over, McElwee is visible in successive long shots, in each of which he is further from the camera, as if to say that for McElwee the director, the value of the lovelorn character McElwee has been playing, this particular reflection of himself, is beginning to diminish. But McElwee’s subsequent visit to Columbia, South Carolina, quickly reveals that he will be staying with the character awhile yet. After McElwee, standing by the Congaree River, delivers a monologue about Sherman’s destruction of Columbia, he steps back and seems to lose his footing in the weeds by the river, then apparently “loses his footing,” when he comes upon Joyous Perrin, an attractive, sexy nightclub singer, performing Aretha Franklin’s song, “Respect,” in a parking lot. As with Winnie and Jackie, McElwee provides no laughter at Perrin’s expense; and while she is certainly attractive, he seems less interested in Joyous as a possible mate than in her commitment to her artistry.32 When Joyous leaves for a nightclub tour in preparation for her planned move to New York City to further her career, McElwee decides to visit one more old flame before returning north himself.

Of McElwee’s relationships with women he knew before beginning what would become Sherman’s March, his involvement with Karen seems the most substantial, though there is no evidence that for Karen their relationship was ever more than an affectionate friendship. Like Joyous, Karen is not material for humor; she is a lawyer and a feminist (we see her marching in support of the Equal Rights Amendment). Nowhere in Sherman’s March does McElwee himself, or at least the McElwee character, seem less mature and a less likely mate: as McElwee says in voice-over, “Bumbling around with my camera, I don’t really know how to film these things and I’m ruining our friendship.” Nowhere in the film is McElwee as filmmaker more evident: after his first conversation with Karen, he films himself with his filmmaking rig in a full-length mirror, the only time this happens in Sherman’s March (a premonition of this self-portrait has occurred earlier: as he hugs Joyous Perrin good-bye, we see McElwee’s back in long shot in a mirror).

Further, during his final conversation with Karen, she confronts McElwee’s filmmaking. Just after McElwee asks, “Why aren’t you in love with me?,” he snaps his fingers in front of the lens to make a slate for this roll of film, and Karen tells him to stop filming. “That’s cruel,” she says. McElwee replies, “No, it’s not cruel,” but Karen is adamant: “It is. Stop.” A moment later he resumes filming, but it seems clear that this is the end of the road, not only for this relationship, but for McElwee’s use of his camera to instigate (or to pretend to instigate) relationships. Our last glimpse of Karen is at a lake, where she turns her back to the camera, saying “Stop it. You stop it.” McElwee’s visit with Karen suggests that his commitment to the role of lovelorn sad sack is running out of gas (like his sports car and the leaky container Cam, Karen’s boyfriend, brings to get the car started), while his acceptance of himself as a filmmaker is becoming more complete.

What remains is an extended denouement that includes McElwee’s visit to the spot in Charlotte where the Confederacy officially died; the serendipitous discovery that Burt Reynolds is in Charlotte and McElwee’s unsuccessful attempt to make contact with the actor (“The production staff informs me that I’ll be arrested if they catch me on the set again”); his visit to the General Sherman statue at the southeast corner of Central Park (filmed by Michel Negroponte); and his return to Cambridge, where he explains that he has gotten a job teaching filmmaking (we see Sever Hall on the Harvard campus, where filmmakers-teachers still have their offices). At Harvard McElwee begins auditing courses, one of them a music history course taught by a young musician, Pam, who McElwee finds attractive. Sherman’s March ends during a concert at Boston’s Symphony Hall where McElwee watches an orchestra and chorus (including Pam) perform Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.”

That McElwee’s travels through the South conclude with his visit to a monument to the death of the Confederacy is suggestive on several levels. The Civil War involved the dividing of America into two distinct entities and the separation of American history into two eras: before the war, when, as historian Shelby Foote suggests in Ken Burns’s The Civil War [1990], the United States was a plural noun, and after the war, when “the United States” became singular. As he travels the South, McElwee is of two minds: he remains a child of the region he travels, seemingly quite comfortable with his personal history and the people he meets, and he has become a northern intellectual, visiting his native region and exposing its sometimes engaging, often bizarre dimensions. This schizoid identity is expressed in the doubling of McElwee as a character–voice-over and in the doubled gaze of his character–camera. Further, in planning, shooting, and editing Sherman’s March, McElwee was engaged in two separate but related activities: the apparent desire for a romantic relationship and the quest to complete his first feature-length film, a new kind of documentary.33 While, at first glance, McElwee’s concluding Sherman’s March with “Ode to Joy” may seem simply an amusing ellipsis that suggests that his quest for a mate continues, a closer reading suggests that the film’s mock-triumphant conclusion is a confirmation of McElwee’s maturation as a filmmaker: he has been hired by one of the most prestigious universities in the world to teach filmmaking and he has completed the film we have just finished watching.

In her canonical novel, O Pioneers! (1913), Willa Cather depicts two fundamentally different kinds of passion. The romance between Marie Shabata and Emil Bergson, who fall in love and are murdered by Marie’s husband in the midst of their first erotic encounter, represents a form of youthful passion distinguished by its fierce necessity, its sharp desire, and its inevitable brevity. The novel’s other form of passion is represented by protagonist Alexandra Bergson’s creativity in transforming wild land into productive farmland (her relationship with the land is described in more erotic terms than any other relationship in the novel). At the end of O Pioneers! Alexandra does find a human mate, her old friend Carl Linstrum, but it is clear that their friendship is based in large measure on Carl’s recognition that Alexandra’s fundamental commitment is to her creative urge, expressed in her passionate relationship with the spirit of the land. O Pioneers! and Sherman’s March are, of course, worlds apart, but McElwee’s articulation of himself as a double character throughout his film suggests a very similar understanding of the complex nature of passion. In frustration after her failure to instigate a relationship between DeeDee and McElwee, Charlene Swansea complains, “How can you be a filmmaker if you never have any passion!” McElwee answers with his only heated comment in Sherman’s March: “I have plenty of passion.” This passion, however, is not for the women he meets during the film, but, like Alexandra’s, for the creative urge that is fueling the making of this film.

The pretense of McElwee’s search for romantic love in the South is really a vestige of the filmmaker’s youth (at the time when McElwee was completing Sherman’s March he was the same age—thirty-nine—as Cather was when she was writing O Pioneers!). On the other hand, McElwee’s creative passion for making Sherman’s March, which throughout the film always takes precedence over his enacted desire to find a romantic partner, is evidence of his adulthood: McElwee’s “march” through the South is ultimately a rumination on the experience of filmmaking itself as well as a testament to McElwee’s recognition that, whatever else he may be or may become, fundamentally he is determined to be defined, to define himself, not by his family, his native region, his education, or his mate, but through his creative passion as a film director and its results.

NESTING DOLLS: TIME INDEFINITE