7

Robb Moss

Like Ross McElwee, Robb Moss earned his M.F.A. in filmmaking from MIT, studying with Ed Pincus and Ricky Leacock, and he became McElwee’s colleague in the Visual and Environmental Studies Department at Harvard in 1983 (Moss is now Senior Lecturer in the Visual and Environmental Studies Department, as well as a creative advisor for the Sundance Documentary Labs). Further, like McElwee, Moss established his reputation with films—The Tourist (1991) and The Same River Twice (2003)—in which he appears as a character. In 2004 Moss described his relationship with McElwee:

People who don’t know anything about us sometimes write to me as Ross. They don’t even mean to reference Ross; they’re just conflating Robb and Moss. And we’re not only colleagues, we’re close friends, who look enough alike that we could be brothers. And we were in Africa about the same time in the early Seventies. Our families often vacation together. Our wives are very good friends. It’s bizarre. . . .

Ross was a year or so ahead of me at MIT. The fact that our films seem related to each other probably has less to do with each other’s films as such, and more to do with whatever originally drew us to MIT and our initial influences there—the people that we knew and the autobiographical films that were the dominant trope of the place.1

The commitment of the two men to personal documentary may be, as Moss suggests, a function of their early development and their influences at MIT, but their filmmaking careers have in certain instances seemed to be in conversation with each other. Moss is one of several friends who get together for a low-key bachelor party just before McElwee’s marriage to Marilyn Levine in Time Indefinite (1994), and we see Moss at the wedding; and in the final scene of Moss’s The Tourist, McElwee and Levine and their infant son Adrian are seen with Robb and Jean Kendall and their adopted daughter, Anna—the climax of each film is the arrival of a longed-for child.2

The considerable interplay between Moss’s and McElwee’s lives and careers can, however, obscure the distinctions between them. While McElwee has been consistently devoted to personal documentary for decades, Moss has always explored a variety of approaches to filmmaking. The Tourist is a personal documentary in the McElwee mode, but it is the only film in which Moss uses voice-over; and Moss’s other films reveal a wide range of interests and procedures. In 2008, for example, Moss and Peter Galison, professor of the History of Science and of Physics at Harvard, completed Secrecy, a feature about the recent history and the dangers of governmental secrecy; and as this is written, Moss and Galison are in the early stages of a film about the only licensed, operating, underground permanent nuclear waste facility in the world.3 Moss’s most remarkable film, The Same River Twice, is a personal documentary, but it is not focused on Moss himself or his family. Like Secrecy, it reveals Moss’s ongoing propensity for using filmmaking as a means of educating himself, in this instance about how a number of the close friends of his youth have changed during the interval of twenty years—as measured by how they respond to the imagery of their younger selves in Moss’s earlier film, Riverdogs (1982).

RIVERDOGS: A POSSIBLE EDEN

By the time he arrived at MIT in 1977, Moss had finished one film: The Snack (1975), an exercise in surrealism made when Moss was an undergraduate at University of California-Berkeley (where he studied film with William Rothman). In 1978, he took the fall semester off to shoot Riverdogs, which was his thesis film (he graduated from MIT in 1979). Moss had spent a number of years working as a river guide on western rivers, and Riverdogs is a 30-minute record of a thirty-five-day, 280-mile pleasure trip through the Grand Canyon by Moss and a group of river guide friends (fig. 33), or, as he says in one of the introductory texts in The Same River Twice (2003), which recycles imagery from the earlier film, “one of my first films about one of my last river trips.” Riverdogs is a poetic evocation of a particular experience shared by Moss and a group of friends, but not an overtly personal film. Moss does not appear as a character at any point (though in one instance, a river rafter addresses a comment to him); generally he functions as the invisible observer characteristic of early observational cinema.4

Riverdogs begins with a visual text—“I used to be a river guide. My friends and I worked for a rafting company, lived in things like tepees and tree houses, and spent close to six months of each year out of doors. In our spare time we took our own river trips. I used to think I would always live on rivers”—as we first hear, then see cars arriving at the Colorado River before dawn (a text indicates that it is “MILE 0/Lee’s Ferry, Arizona”). The film ends once the river trip has concluded, as the group packs up and gets back on the road. In between, we see the group making their way down the river, playing games, hanging out, scoping out the more difficult rapids, cooking, hiking into side canyons, talking, singing, sunning, reading, kayaking, and in some instances conversing about aspects of the trip. In general, Riverdogs alternates between sync-sound passages during which the rafters interact and montages accompanied by the sound of the river, and in a few instances by extradiagetic music.5

FIGURE 33. The “tribe” of Riverdogs, with Robb Moss on far left, holding the camera. Courtesy Robb Moss.

While the trip down the river is the plot (Moss is careful to reveal the gradually changing terrain), several distinctive characters emerge: Barry Wasserman provides some humor, for example, and our attention is regularly focused on Danny Silver and Cathy Schifferle hiking and talking. By the end of the film, we have become familiar enough with some members of the group that when Wasserman and Jim Tichenor vocalize the group’s debate about whether to stay on the river for one extra day, as Tichenor urges, or conclude the trip, as Wasserman is suggesting, their personalities, even their positions in the debate, seem familiar. This is not to say that these individuals are the protagonists of the film; Moss’s focus remains consistently on the group working together. Our growing to know some individuals better than others reflects the realities of any group activity and helps to energize the film, the way the periodic rapids in the Colorado energize the river trip itself.

By the time Moss shot the footage that he would edit into Riverdogs, he was already a capable cinematographer: the film is consistently gorgeous, and Moss is adept at filming activities both on land and from inside boats, rafts, and kayaks. On one level, Riverdogs is a contribution to the considerable history of outdoor sporting activity filmmaking (films by and about skiers, and so on) that remains generally under the radar of serious film study. But to see it as merely a celebration of river rafting is to miss the point. This is implicit in the opening minutes of Riverdogs, when, once the river trip is underway, we realize that suddenly the rafters seem to be going about their activities nude. It is during the precise moment of this realization that Moss reveals the title of his film. The word riverdogs seems to designate not simply a group of people on a river rafting trip, but this group who, for a time, are leaving their more conventional lives and selves behind.

As Riverdogs develops, the nudity of the rafters comes increasingly to seem both a metaphor for getting back to basics and evidence of a kind of spiritual engagement with the natural world. Indeed, this spiritual dimension of the trip seems implicit from the beginning of the film, in the particular imagery Moss uses of the group assembling at Lee’s Ferry. The arrival of the vehicles is presented so as to emphasize the headlights of the cars, which create circular reflections and circles within circles suggestive of mandalas and eye-of-god cathedral windows, that is, of the traditional emphasis on circularity of so much religious and spiritual imagery. Further, Moss’s indication that he “used to be a river guide” and that he used to think he “would always live on rivers” frames this particular river trip as not simply a pleasure excursion but a special experience that brought an earlier way of life to a close, at least for Moss.

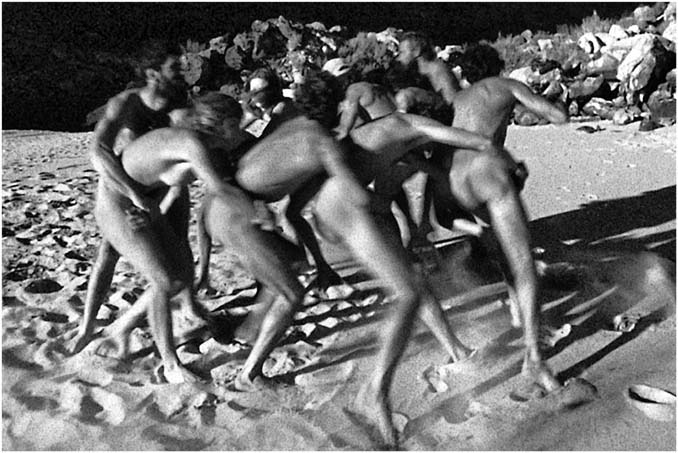

While there is nothing in the action of Riverdogs to suggest that, as a group, the participants in the river trip saw themselves a part of anything like a spiritual ritual, the importance of this adventure to Moss is reflected throughout the film. The fact that he is filming the trip at all, of course, suggests its importance to him; and Moss has explained, “When I shot Riverdogs . . . I wanted to evoke the experience of a river trip, which was what we went back for again and again and again, and what our small community of river guides had fallen in love with. We were like a small tribal group. The film was a bit like salvage anthropology: this way of life was passing, at least for me, and I was trying to get hold of it with a camera.”6 That this river trip is one of many for the participants seems evident in the way that all the members of the excursion seem to know their roles and in the fact that the group seems entirely comfortable with one another (fig. 34). That these sixteen men and women had become something of a “small tribal group” is also suggested by a ritual they perform as they prepare to tackle the final major rapid: they paint each others’ faces in a way that evokes the face painting in Gardner’s Deep Hearts and, of course, in other, more conventional depictions of native peoples.

FIGURE 34. Several Riverdogs play a circle game (the one in the front of the “snake” tries to catch the one in the rear) in Robb Moss’s Riverdogs (1982) and in The Same River Twice (2003). Courtesy Robb Moss.

At the conclusion of Riverdogs, as the roped-together flotilla of rafts and boats drifts toward the point of disembarkation, Moss provides a final echo to the circular reflections that begin the film and their implications: a tracking (or, really, floating) shot circles entirely around the flotilla and the rafters relaxing on it. The “way of life” Moss is depicting is, on one level, quite specific, but on another level, it represents more than just this group of friends. Moss has said that Riverdogs “was an homage to the Sixties, a Seventies film that grew out of Sixties values,”7 and few films do a better job of capturing the spiritual idealism that was such a crucial part of the early moments of the American cultural revolution. As an artifact of a particularly hopeful moment in American culture, at least for a good many young people, Riverdogs stands with D. A. Pennebaker’s Monterey Pop (1968) and William Greaves’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1972); and as clearly as either of those two films, it focuses on a group of young people who demonstrate, throughout the film, a commitment to communal activity, a respect for the environment, a rejection of conventional notions of proper dress, and even—this, being more characteristic of the late 1970s than the 1960s—a commitment to gender equality so fundamental that it seems automatic: women and men participate equally in virtually every aspect of the river trip without the slightest bit of rhetoric or self-congratulation.8

Recent decades have produced a host of critiques and satires of 1960s idealism; T.C. Boyle’s novel, Drop City, is representative of this tendency, as is Ed Pincus’s One Step Away. Moss’s idyll makes clear that, however silly or problematic we may now find this brief idealistic moment, it was not the property simply of hippies and hypocrites, but in some instances, of women and men who were, at least for a time and in a particular circumstance, capable of living these ideals. That these women and men were river guides suggests a considerable level not merely of skill but of the maturity and responsibility necessary for ensuring the safety of those they guided down rivers. In Riverdogs the physical beauty of these remarkably fit young people and their ability to work and play effectively together evokes a golden age, a possible (if momentary) Eden.

THE TOURIST: “FREELANCE EDITING”

Moss’s first autobiographical documentary, Absence (1981), which is not in distribution—it exists currently as a single 16mm print—was completed in 1981. It is a series of vignettes of family and friends, recorded during a single trip home at the end of 1980. As Moss explains in the film’s introductory text, “I had been living in the East and flew home to California for the holidays. My high school ten-year reunion comes and goes, my mother and I take walks, my father tells jokes. I am still not used to the idea that things change.” Absence communicates something of Moss’s feeling of being a stranger in his own life—and it does so entirely without narration, though the vignettes do provide enough background information for viewers to make sense of events. Several people who would become characters in Moss’s later films are introduced, including his (divorced) parents and Barry Wasserman, who appears in a scene in a men’s steam room—the nudity here a premonition of Riverdogs. As would be true in The Tourist (1991) and The Same River Twice (2003), we can hear Moss behind the camera as he interacts with his classmates, friends, father and mother; like McElwee in Sherman’s March, Moss holds the camera on his right shoulder, so that it observes his conversations from a detached position to screen right of where those he is talking to are looking, and as in the McElwee film this tends to create a kind of detachment, an implicit “absence,” as if Moss is now part of another life, a filmmaking life in the East, and is watching himself visit a world he has left behind.

During the ten years after leaving MIT, Moss supported himself as a freelance cameraman for a variety of projects produced in Ethiopia, Belize, Nicaragua, Liberia, Hungary, and Japan, as well as in the United States; and one of the two main topics of The Tourist is these experiences filming, as a “tourist,” in far-flung locales. The Tourist begins with the sound of children singing a song (“sardines and pork and beans” is a repeated phrase; the song suggests that the singers are tired of eating the same thing every day),9 and images of Liberian children pretending to be filmmakers, using “cameras,” “microphones,” and other equipment made from bamboo and revealing in their actions and posture how carefully they’ve been watching Moss and his colleagues. Moss, in voice-over, then explains, “When I was a kid, I loved the movies. Growing up, it seemed a perfect life to travel and to make movies. Filming other people is how I make my living. Sometimes I shoot my own films; sometimes people hire me to shoot theirs. In either case, certain problems arise.” While the children’s pretending to shoot film is funny, it is also the first instance of many in the film during which Moss reveals how the presence of the camera transforms and exploits what it captures.

After the opening directorial credit, a second sequence reveals the film’s other main topic. After shots of the wedding of Moss and Jean Kendall (at Ed and Jane Pincus’s farm in Vermont), Moss, again in voice-over, explains that he and Kendall have been struggling to have a baby: “We don’t know why it’s not working. Jean suspects it’s her, and I think it’s me.” Moss’s comments are accompanied by Kendall playing on their bed with a cat, continuing to tease it even though it bites her hard enough to make her shriek. The scene is quite funny, though as the film develops, these playful cat bites come to seem a premonition of some real physical and psychic pain. The film’s prologue concludes with a single shot of an oil rig pumping, made from a moving car—a wry metaphor for Moss and Kendall’s sexual activity—followed by the film’s title credit.

Early on, The Tourist seems to be intercutting between episodes relating to issues raised by Moss’s experiences as a freelancer and the problems he and Kendall are having with pregnancy. After the title credit, Moss is in Texas, shooting material for a film on hunger in America; then, in Ethiopia where he is working as a cameraman for what would become Faces in a Famine (1985) by Robert H. Lieberman: we see moments from the finished Lieberman film on television (including a mother with a starving child) interspersed with shots Moss made in Ethiopia for himself, including a fight. This sequence concludes with Moss in voice-over explaining, “It is often the case that the worse things get for the people you are filming, the better that is for the film you are making.” This statement seems relevant not only to the starving baby and the fight, but in a very different way, to the sequence that follows: Moss’s documentation of a trip he and Kendall and his mother, Laurie Moss, take to Death Valley. Moss explains that his mother, recovering from a car accident, wanted to go somewhere level where she could walk; “Jean, someplace where nothing could grow.” During the following sequence Kendall and Moss’s mother get the giggles and whatever psychic “low points” led to the Death Valley trip seem for a moment to disappear.

As The Tourist continues, the personal and the professional become increasingly imbricated. For one thing, Moss’s professional visits to Africa, Europe, Central America, and Asia are interwoven with several personal trips Kendall and Moss take: to Portugal on a delayed honeymoon before another pregnancy is due to come to term; to Belize when they accompany a friend who is writing an article for Travel and Leisure; and to the island of St. Martin, a gift from Laurie Moss who has won the trip in a raffle. Midway through the film, Moss explains in voice-over, “The thing about freelancing is that the phone can ring anytime and take you anyplace to make a film about anything.” This description is implicitly relevant to the course of any pregnancy, and of Kendall’s pregnancies in particular: the trip she and Moss take to Portugal as a “postponed honeymoon” is interrupted by Kendall’s first miscarriage. Moss’s comment is also an explanation of the seemingly chaotic editing strategy of The Tourist. Any particular cut can provide a new view of what was recorded in the previous shot or an image from a world away.

Within the continual movement from one place to another, certain motifs develop. For one thing, Moss’s way of seeing is increasingly affected by his concern with Kendall’s getting pregnant, by her miscarriages, and at the end of the film by the experience of adopting a daughter: whether he is working as a freelancer or recording his own material in off hours, children are much in evidence. Another motif involves the way in which film imagery can obscure as much as it reveals. At the end of the sequence of the Death Valley trip, as Kendall and Moss’s mother are giggling together, Moss indicates that sometimes, when he is not really a part of what he is filming, “I begin to look around and film what I imagine is the poetry of the situation.” At the word imagine Moss cuts to a sequence of images shot in Liberia, beginning with young girls walking along a jungle path, followed by “poetic” imagery of a woman nursing a baby on the porch of a cabin as she speaks with a neighbor. At the end of the sequence, Moss indicates that, when he had the woman’s comments translated, he learned that she had been complaining to the neighbor about “what a pain in the neck we were.” A “poetic” moment is immediately transformed into irony.

Still another motif reveals the limitations of spoken language. During a fact-finding trip to Nicaragua, Moss wanders into an earthquake-destroyed church in Managua and gets into conversation with a young soldier. In voice-over, he explains that his Spanish is very limited (as a swimming stroke, the dog paddle), then describes his attempt to mine the soldier’s feelings about this picturesque ruin: “I more or less asked him what he felt here, and he more or less told me that he felt a breeze.” During a taxi ride with Percival Usher in Belize, a conversation about Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Samoza seems to lead to Percival’s saying that Samoza is a “liar”—apparently a political judgment—though Moss and we soon realize that “liar” is simply Percival’s way of pronouncing “lawyer.”

Such amusing misunderstandings are often part of the quite serious issue of the sociopolitical power implied by the camera and the exploitive nature of filmmaking. Even the opening sequence of the Liberian kids playing filmmaker suggests a disparity between the haves and the have nots: the American crew can shoot real film; the Liberian children can only pretend to. This disparity is powerfully evident in the footage of starving Ethiopians recorded for Faces in a Famine, especially the imagery of a starving, fly-covered baby and the child’s mother: the Lieberman film is obviously an attempt to bring needed attention to a human disaster; nevertheless, its emotional power comes from its imagery of people who not only cannot represent themselves but are at the mercy both of a terrible drought and of cameraman Moss and the rest of the filmmaking crew. The issue of exploitation seems evident in nearly all of the episodes Moss presents, often in complex and subtle ways.

During the visit to Managua, Moss films George, a member of their group who wants to take a snapshot of a young girl who sells watermelon. Though the girl is embarrassed by the attention, George takes her arm and positions her for some picturesque Polaroids. While George means no harm, he seems oblivious to the fact that this young girl apparently must work to survive. George does plan to give the girl one of the snapshots but is quickly surrounded by a group of mostly young Nicaraguans all of whom now want a picture, and George becomes concerned that a fight will break out. The medium is the message here; whatever the value of the snapshot George takes of the girl, Moss’s record of this moment reveals the power of the photographer and his camera within this economically challenged society—and of course, the significance of George’s interaction with the young Nicaraguan girl has been made obvious to the mostly young people on this Managuan street by the presence of Moss with his even more visible sync-sound rig. As Moss says in voice-over, “In the group I’ve noticed that as soon as any of us wants anything, then this wanting seems to invoke this chasm of inequality.”

Moss seems aware of this issue even during what might seem to be innocent moments. For example, during a taxi ride in Percival Usher’s car, the passengers (Moss, Kendall, and their friends) ask Usher how many siblings he has. When he replies twenty-four, the women ask if he can name all his sisters and brothers, and Usher does. Usher’s naming his siblings provides amusement for his momentary employers (and for us), while revealing a pattern that distinguishes First World and Third World peoples: the size of Usher’s family, given this family’s limited economic resources, is the inverse of the lives of the visiting Americans, and implicitly of viewers of The Tourist, who have found their way to the kinds of screening rooms likely to exhibit an experimental documentary. This moment in the taxi with Usher concludes with shots of Jean Kendall looking pensively out the window of the cab, revealing Moss’s awareness of the irony of Usher’s wealth of siblings and Kendall’s frustration at not being able to produce a single child. But here too, the camera is subtly exploitive. A few moments earlier, as Moss is creating context for the trip to Belize, his voice-over indicates that “though I’m sure Jean would prefer I hadn’t, I brought my camera.” The amusing but poignant irony of the distinction between Usher’s situation and Kendall’s may be a pleasure for viewers engaged with the themes Moss is developing in The Tourist, but it depends on Moss capturing and revealing his wife’s subtle discomfiture.

Of course, filmmaking isn’t only a form of one-way exploitation; it can also be a means of connecting disparate realities, not simply within the editing but during the filming. This, too, is evident in that opening sequence of the Liberian kids imitating Moss and the rest of the filmmaking crew. The kids are clearly enjoying their mimicry of a Western obsession, even if they don’t have access to the real equipment. And this idea of connection is developed and comes to a kind of conclusion in two different ways during the second half of The Tourist. First, the original meeting with Percival Usher, recorded in the ride in the taxi, leads to something more than a business arrangement. Moss asks Usher if he might spend a day hanging out with him, and Usher agrees, and while, “of course, everyone, especially myself, is a little too polite,” Moss, Usher, and his neighbors seem to take pleasure in their time together and in Moss’s filming.

Later, after Kendall has experienced a second miscarriage, and once she and Moss have begun the process that will lead to their adopting a baby girl, Moss returns to Belize for a freelance job and goes to visit Usher. During this visit, Moss learns that while Percival and Minerva Usher do have two young children, Juni and Monica, they too have had experiences with miscarriages. They have lost two pregnancies, and Minerva is pregnant again and is having difficulties. This final conversation between Moss and Usher includes the usual subtle miscommunications; nevertheless, it is clear that whatever their differences, the two men have an important experience in common, and when they say good-bye, both hoping that Usher will have the son he hopes for and that he and Moss will meet again, it is clear that something like a real friendship has formed between these two men from very different societies and social classes.

Moss’s meeting with Usher occupies much the same position in The Tourist as the wedding of Lucille and Melvin occupies in McElwee’s Time Indefinite: it heralds the resolution of the struggle of Moss and Kendall to become parents, though this resolution has already begun to develop before Moss’s last trip to Belize. After their trip to St. Martin, where on a whim Moss and Kendall tour a new time-share complex, Moss includes a photo montage of Kendall’s postcard collection (all the postcards we see are of idealized families and children). This is the second of three photo montages in the film—the first is the visual accompaniment to Moss’s description of Kendall’s painful miscarriage in Portugal—and in both instances still photography seems to suggest an interruption of the organic motion of life, the experience of life breaking down, the stilling of hope. The postcard montage is followed by Moss’s voice-over revelation that he has virtually given up on becoming a father: “As time went by, I too stopped believing and in so doing, also stopped being able to conceive the future.”

Without a sense of the future, life ceases to make sense, and Moss’s subsequent visit to Japan (“one of the only places on Earth where I not only don’t stick out because I’m filming, but where I fit in—this is not to say I feel at home”) feels surreal and seems to suggest that without the possibility of family, Moss is psychically lost. He spends his final night in Japan wandering the streets of Tokyo, filming this and that: a kind of dark night of the soul. Now that conceiving their own child and bringing a pregnancy to term has come to seem hopeless, Moss and Kendall have considered adoption, and Moss confesses, “At first the whole idea of adoption seemed strange to me”; “I had this awful thought that I might reject an adopted child as foreign, as an immune system can reject an organ transplant.”

In the following sequence The Tourist returns to the Death Valley footage in which Moss and his mother are goofing around with Moss’s camera (“No matter how old my mother and I get, her face is always ridiculously familiar”), then introduces his father on a visit to Boston, where the two search for the graves of the Moss family in a Jewish cemetery. Filming his long-divorced parents leads to Moss admitting that he is “finding that my desire to parent is overcoming my desire to mix my genes with Jean’s genes,” and this realization leads to Moss and Kendall’s “auditioning to become parents.” They work with an adoption agency that sends biographies and pictures of prospective parents to pregnant women who have decided to give their babies up for adoption. This new direction, with its new kind of hope and its own mystery, involves Moss for the first time becoming a photographic subject rather than the man with a camera, which is emblemized by the film’s third and final photo montage: still photographs of Moss and Kendall in all of which Moss has his eyes closed. This is both very funny and a revelation of how fully Moss himself feels the power of the camera.

During the final sequences of The Tourist, Moss intercuts between his and Kendall’s meetings with “Lee” and references to Moss’s life as a freelancer, which in a serendipitous conjunction of events includes his filming for a videotape manual about caring for newborn babies. In the final sequence, we see Anna, two hours old; Kendall speaking with “Lee” just before she leaves to go home; and, to the accompaniment of the “sardines and pork and beans song,” a shot of Anna in close-up as Moss is saying, “One of the secret pleasures about becoming a parent, a pleasure at least kept secret from those of us too distracted by our lives to know better, is falling in love with your children.” The final shot of the film is from a home movie made the day before Anna turns fourteen months old; sitting on the floor in a circle are Ross McElwee, Marilyn Levine, and Adrian McElwee, and Kendall and Anna, who, seeing that Moss is filming, toddles toward the camera, smiling.

VOYAGE OF LIFE: THE SAME RIVER TWICE

His historical researches, however, did not lie so much among books, as among men; for the former are lamentably scanty on his favourite topics, whereas he found the old burghers, and still more, their wives, rich in that legendary lore, so invaluable to true history.

WASHINGTON IRVING, ON DIEDRICH KNICKERBOCKER IN THE “HISTORICAL” NOTE THAT PRECEDES “RIP VAN WINKLE” IN THE SKETCH BOOK

Is there a more American story (and in our relentlessly globalizing, digitizing world, a more human story) than “Rip Van Winkle”? The tale of a man who falls asleep for twenty years, then returns to his home town to find everything changed, remains as relevant to our understanding of our experience as Americans as it was nearly two centuries ago. Of course, there is much to recommend the Irving story: it is engagingly written, witty and amusing; and it evokes the changes from Dutch colony to British colony to American nation that must have seemed fascinating to its original readers. Further, it suggests the hunger of an earlier generation of Americans to have a mythic national past like the citizens of other great nations—even if American writers needed to create the requisite legendary tales themselves, tongue in cheek. But what has always made “Rip Van Winkle” most powerful is the idea of a man, long absent from his family, friends, and home town, walking back into his previous life and trying to make sense of the changes two decades have wrought, both in his surround and in himself.

The drama of returning home after long absence was certainly not invented by Irving (perhaps Homer can take credit for it), but it seems particularly relevant for the citizens of a nation that during several centuries was in the throes of geographic expansion and the movement of a western frontier, and that during the past hundred years has experienced a population explosion and endless transformations in technology and thought. Not surprisingly, the drama of Rip’s return home has been reexperienced by a good many characters in the American literary canon. The most dramatic moment in Willa Cather’s O Pioneers!, for example, occurs between parts 1 and 2 of the novel: at the conclusion of “The Wild Land,” Cather’s protagonist, Alexandra Bergson, realizes that she is committed to the land of the Nebraska Divide and has come to believe that she can transform a wilderness into productive farmland: “Under the long shaggy ridges, she felt the future stirring.” The turn of a page jumps the reader thirteen years into the future, causing readers to play Rip Van Winkle: we reenter the farm where Alexandra lives and discover the remarkable changes that have occurred “in our absence.” Of course, the very suddenness of this change, at least for readers (we had expected to see the process of the transformation), like the sudden change that occurs in “Rip Van Winkle” between the moment when Rip falls asleep and wakes up—twenty years disappear between paragraphs—is suggestive of the way in which aging in any society, and perhaps particularly in ours, always seems, at least in retrospect, to have occurred very quickly: the older we get, the more quickly durations of time seem to have flown by.

The drama of a return after long absence is also the subject of Robb Moss’s The Same River Twice, though here, the return takes place on several different levels.10 To make the new film, Moss returned to Riverdogs, which had virtually disappeared soon after it was made, and recycled substantial portions of that film into a personal documentary during which he and five of the original Riverdogs return to Moss’s cinematic memory of their 1978 river trip through the Grand Canyon and confront the implications of the twenty-year gap. To the extent that, as suggested earlier, Riverdogs has become an artifact of the worldview of a particular generation (or at least of one subculture within a generation) and a demonstration of a set of social ideals, the return of Moss and his five friends to an earlier time is not simply the story of six individuals; it is emblematic of the experience of that generation, and perhaps to some extent of the experience of most generations in moving from youth to middle age.

By the time of The Same River Twice, Moss had found a way to be a character in a personal documentary virtually without being visible and entirely without using vocal narration. It is clear throughout The Tourist that Moss is not entirely at ease either in front of the camera (every time we see him, and then only in still photographs, his eyes are closed) or as narrator: his discomfort, subtly evident in his voice, confirms the theme of Moss being a “tourist.” In The Same River Twice Moss is a presence throughout, but he is visible only in two very brief instances: early in the film during a sequence when Barry Wasserman is giving Moss a tour of his medicine cabinet (we see Moss momentarily in the medicine cabinet mirror); and late in the film, again with Wasserman and again in a mirror, when Wasserman is getting dressed after a final radiation treatment for testicular cancer; in this instance, Moss’s response to Wasserman’s realization that saying thank you and good-bye to the radiation nurses was more emotional than he had expected it to be is visible (and audible). Throughout The Same River Twice, however, the five friends (as well as Wasserman’s spouse Deb and Danny Silver’s husband, Peter) speak with Moss as he films. In The Tourist, the people Moss films are usually responding to the presence of a motion picture camera; in The Same River Twice, they are generally responding to the presence of Moss himself, often to his questions and comments, and in general willingly collaborating with the record he is making of their shared past and present.

Moss is also implicitly present in The Same River Twice through brief visual texts. Three of these, in conjunction with visual images from Riverdogs, introduce the action of the film. “1978” temporally locates the action we see in the recycled images, and two longer texts, “We used to be river guides. For many years my friends and I lived an unscheduled, communal, outdoor life” and “I spent most of this trip [that is, the trip in Riverdogs] behind the camera, shooting one of my first films of one of my last river trips,” confirm the gap between the 1978 river trip and Moss as veteran filmmaker “now” (twenty-five years later: The Same River Twice was shot from 1996 to 2000 but was not finished until 2003). Often during The Same River Twice visual texts are used as segues between then and now, and to provide context for the lives Moss is reintroducing us to. Soon after the opening images of several nude Riverdogs and the introductory texts, Moss presents the sync-sound sequence from the earlier film during which Barry Wasserman and Jim Tichenor debate whether to stay one extra day on the river. A direct cut from Barry in Riverdogs to Barry in 1998 fixing a medicine cabinet and the text, “Barry,” followed by “20 years later,” confirms the gap in time that is evident in Barry’s face, as well as the distance between an earlier “unscheduled,” “outdoor” life and his current domestic circumstances.

As The Same River Twice continues, Moss uses visual text as a means of creating subtle ironies. For instance, during the opening documentation of Barry’s domestic life with Deb and his children, Moss superimposes three successive texts: “Barry is finishing his fourth year as Mayor of Placerville, California”; “He is running for re-election”; and “Barry works full-time as an administrator of a psychiatric care facility.” A few minutes later, we learn that Cathy Shaw (originally Cathy Schifferle, then Cathy Golden) “is serving her 9th year as Mayor of Ashland, Oregon,” as we see her at what appears to be a city council meeting. Since we have already met Wasserman and Shaw as young people, nude, on the 1978 river trip, the information about their mainstream jobs is amusing. This idea is confirmed when Wasserman mentions that a fellow worker expressed surprise at seeing him in shorts, and Moss cuts from Wasserman in his office to a shot of him, naked, walking into a canyon along the Colorado.11 On one level, these texts help to demonstrate how the intervening twenty years have changed Wasserman and Shaw; but on another, more subtle level, they also reveal that less has changed than meets the eye: the fact that both worked as river guides in 1978 is evidence that, however unmoored their lives in Riverdogs might look to a later generation, they were then, as they are now, fundamentally capable and responsible individuals on whom others can depend.

These and subsequent context-setting visual texts allow Moss to function in a double role. He is, on one hand, an informative, sometimes ironic “narrator,” who exists at a several-year temporal remove not only from the events of Riverdogs but from the events documented during the shooting of The Same River Twice. And he is on the other hand an engaged participant in the lives of his friends during the period from 1996 until 2000. He films them; we hear him ask them often-intimate questions and respond to their answers; and sometimes (in a manner that evokes a particularly McElwee-ian form of presence), one or another of his friends will reveal his physical presence as filmmaker: Cathy Shaw dances with Moss as he is filming during the party after her marriage to Rick, and Danny Silver laughs and says, “Excuse me!,” as Moss passes close to her while she is leading an aerobics session.

It is crucial for The Same River Twice that we feel not only the temporal gap between 1978 and the late 1990s but that we are aware that the lives of Moss’s friends are continuing to evolve. As Moss has explained, “The now had to generate its own past, so that when you come back into people’s lives, you know them and you can refer to the things that have been happening to them; you have enough dots along that trajectory so that you can graph it emotionally. This happens, that happens; people are getting married, are finding out they have cancer, are being treated, are having children. That’s how our lives are. And that becomes the past of the film. Otherwise, it would be The Same Stagnant Pond Twice.”12

The Same River Twice does demonstrate clear distinctions between the different speeds at which lives transform. While Wasserman’s and Shaw’s lives seem comparatively full of change (Wasserman’s bid for a second term as mayor fails, he completes radiation treatments for his cancer; Shaw is first bidding a formal good-bye to a man who has conducted concerts in Ashland; she explains that she has quit her job at Planned Parenthood and is looking for less mind-draining work; she gets married and goes on a honeymoon), Jim Tichenor’s apparent aversion to change is part of the humor of the film. Early on, he shows Moss the site of the home he plans to build. Later, we see Tichenor explaining to Moss that the dimensions of the home (the foundation is now dug) are based on the Fibonacci series of numbers; but after a text, “1 year later,” Moss returns us to the same spot where nothing seems to have changed: we laugh at what seems Tichenor’s stasis—though we realize that things have been changing, however slowly, when men arrive to pour the concrete foundation.13 Life is change—as the title’s reference to Heraclitus’s famous line suggests—though its velocity varies. The character in The Same River Twice whose life seems closest to stasis is Wasserman’s mother who, as her son explains to Moss, can’t find a way to enjoy her old age but also cannot die; when Wasserman visits her, the mother and son are seen on the Pacific coast where Mrs. Wasserman draws her son’s attention to a tiny boat out in the ocean; Moss cuts to the distant boat, seemingly stationary in the water.

Moss uses the filming of The Same River Twice not merely to document how the individual lives of the once-Riverdogs are changing during the period from 1996 to 2000 but to show how their relationships with each other have continued to evolve as part of their current experience: Danny Silver, for example, provides the toast at the party following Cathy Shaw’s marriage to Rick, and Moss records the moment. A different form of interchange can be understood to take place both within The Same River Twice and during an implicit extra-filmic moment. During one of the sync-sound excerpts from Riverdogs, the group is meeting to decide something (perhaps how to negotiate the final major rapids) and Wasserman says, “Let’s present our plan, Pep [this person is not identified], and then Cathy can present her plan.” Shaw says she really doesn’t have a plan to present, and Wasserman responds, “Okay, well, you can just criticize ours.” Moss presents this moment twice: first, to Shaw, who responds, “Well, fuck you, Barry!” She glances toward Moss, then says, “I didn’t say it then, but I thought it.” Moss then repeats the excerpt and reveals Wasserman’s response: he is clearly ashamed to have embarrassed Shaw and points out how a wave of Shaw’s hand subtly reveals her frustration with him: “Look at her hand; the last thing on earth she wants to see right now is my snide face”; then, clearly moved, he says, “Oh god. Sorry, Cathy.” This apology, decades after an implicit insult, is poignant partly because we can infer that Shaw will, at some future date, see this sequence and hear Wasserman’s apology.14 In this instance, Moss uses his filmmaking to resolve (or to attempt to resolve) the friction between Shaw and Wasserman that Shaw clearly still feels so many years later.

The twenty-year gap between Riverdogs and the action in The Same River Twice is also significant in a cinematic sense for Moss for at least two reasons. First, making The Same River Twice allowed him to return to Riverdogs, which had never had the attention it deserved, and recycle much of its imagery and what that imagery represents to Moss into a new form for a possible new audience. The original decision to film the Grand Canyon rafting trip was one of Moss’s first extensive attempts to function as a serious filmmaker, and editing the film involved considerable time and labor. The fact that Riverdogs was not widely appreciated does not mean that the experience of making it wasn’t important for Moss.

Second, The Same River Twice charts the change from shooting in 16mm, still standard for independent filmmakers in the late 1970s, to shooting in video, which Moss uses for all the material shot in the 1990s—a change that is continuing to transform the process of filmmaking for many filmmakers. There is nostalgia in The Same River Twice not only on a personal level (clearly Moss has fond memories of his life as a river guide and his experiences with his friends on their Grand Canyon trip, even if the particular trip documented in Riverdogs was, as he has explained, “a miserable trip for me; my girlfriend and I were fighting the whole time”),15 but on the cinematic level. The particular color palate and visual textures of 16mm seem increasingly a thing of the past, and for Moss, who came to love working with 16mm, this represents a considerable loss. Indeed, the look of Riverdogs seems more akin to the films of Peter Hutton or Bruce Baillie than to The Tourist or to the 1990s imagery in The Same River Twice, and there are filmmakers—Hutton is perhaps the best example—for whom what 16mm offers visually is simply not worth giving up for the increased convenience in production and distribution offered now by digital video.

Moss’s recycling Riverdogs into The Same River Twice also involves a transformation in our sense of the earlier film. In The Same River Twice Moss’s focus on the few sync-sound episodes in the earlier film causes Riverdogs to seem far more “talky” than it is; indeed, the sync-sound sequences of the group playing games; Barry’s joking with the group about “competitive eating”; a conversation with Cathy Shaw and Jeff Golden, lying in their sleeping bags; the conversation between Wasserman and Shaw about the plan for running the rapids; and the debate about whether to stay on the river an additional day are exceptional within Riverdogs, moments of intimacy within a more detached, more mythic, experience: as Moss has said, “I think of Riverdogs as a kind of mural; it has a mural kind of narrative.”16 Further, in The Same River Twice Moss makes no attempt to echo the order of sequences in Riverdogs, choosing instead to use the earlier material to emphasize and clarify what is happening in the present of The Same River Twice and what has happened during the interim between the two films.

What Moss has gained as a filmmaker during the twenty-plus years since he shot Riverdogs is a dexterity with the camera that allows him to film in-close with his friends in a comfortable, intimate way that maintains our attention on them, rather than on Moss and his filming. While the most amusing moments in McElwee’s films tend to be created by the fact of his filming and his complex narration, the most amusing moments in The Same River Twice are more fully a product of what Moss notices and/or of the ingenuity of those with whom he talks. For example, the sequence in Time Indefinite when the Jehovah’s Witness comes to the door of the McElwee home in Charlotte would not be of particular interest were it not for McElwee’s complex relationship, as filmmaker and narrator, to the man and his daughter: particularly his mock complaint about being eligible for the Federal Witness Protection Program because of all the Witnesses that have found their way to him, and his voice-over reflection on what this Witness has said about “time indefinite.” In The Same River Twice Moss asks Barry Wasserman whether he is in a support group for testicular cancer, and Wasserman responds, “Yeah, but they can’t relate; they lost their right testicle. It’s completely different. It’s like the opposite end of the scrotum.” In Time Indefinite we laugh mostly at what McElwee says; in The Same River Twice, we tend to laugh, often with Moss himself, at what Moss’s friends say or do. There are, of course, obvious exceptions to this pattern.

Moss’s maturation as a filmmaker is also evident in his editing (done in collaboration with Karen Schmeer). While Riverdogs is edited in a rather straightforward manner so as to accurately document the trip down the Colorado, The Same River Twice moves inventively between past and present and from one site in the west to another, using sound and image in subtle and evocative ways, sometimes condensing complex events into relatively brief sequences that nevertheless reveal the subtleties of human relationships over time. A particularly inventive sequence midway through the film explores events that led to the now-defunct marriage of Cathy Shaw and Jeff Golden, who, in the interests of their two children, continue to live across the street from one another.

Moss presents an image of Shaw in 1978, climbing, nude, up a rope ladder, as a ringing phone is heard and Golden tells Moss, “I’d better get this” (fig. 35). It’s Shaw. Golden mentions that when the phone rang, he and Moss were watching Riverdogs and that the tape is now paused on a shot of her “frozen, flickering butt.” Moss then cuts to Shaw on the phone, as if she is talking with Golden, and she seems to respond with a vaguely embarrassed “Mmmm”—though it is quickly obvious that Shaw is not on the phone with Golden but on mayoral business.

FIGURE 35. Jeff Golden looks at nude image of Cathy Shaw in Riverdogs, in Robb Moss's The Same River Twice (2003).

During the following minutes, Moss intercuts between Shaw doing various mundane tasks, one of which is describing and offering Moss “our favorite” breakfast (toast of some kind, cottage cheese, and fresh tomato and basil from her garden), and Golden cooking a meat and egg breakfast as he talks with a business colleague on the phone. At one point, Moss superimposes his own conversation with Shaw over imagery of Golden cooking just as Shaw is describing moments during the breakup when she and Golden felt tenderness for “what was passing” (here, Moss fades in a brief image from Riverdogs of Shaw and Golden in sleeping bags, with the sound of the river superimposed, then returns to sync-sound imagery of Golden cooking and talking on the phone). When Golden, now off the phone, offers Moss some of what he’s been cooking, Moss demurs, and Golden says, “You’re all cottage-cheese-and-tomato-basil-and-English-muffined out, huh?” MOSS: “You know that dish . . .” GOLDEN, sardonically: “Six . . . days . . . a week, over there.” Then, as Golden continues his preparations, Shaw’s auditory story continues, until, following a more distant long shot of Golden framed by his kitchen doorway, Moss cuts to a close-up of Shaw, who enacts a kind of shot-countershot, describing the moment in a movie theater when she asked Golden if he were having an affair and, after several evasions, Golden said, “Yes”—and the sequence fades out.

This passage, which I have only begun to unpack, deftly encapsulates a series of emotionally complex moments in the intertwined lives of two people over twenty years. Moss reveals the subtle mix of friendship, affection, nostalgia, disappointment, frustration, annoyance, respect, and self-awareness that continues to characterize their ongoing relationship with each other—as well as their continuing intimacy with him.

Because of Moss’s embrace of change throughout The Same River Twice, the film abjures the kind of resolution that McElwee’s Time Indefinite and Moss’s The Tourist provide. Instead, the film concludes by offering viewers a more expansive version of the choice that is the subject of the opening debate between Wasserman and Tichenor about whether to stay on the river one more day (we see this debate three times during the film). Wasserman wants to move on (“I’m ready to go”), while Tichenor wants to stay (“Look where we are; we’re in the Grand Canyon, and we can be here one more day”). The subsequent lives of these two men, as Moss depicts them, have confirmed these opposing positions. Wasserman has moved on, and being a river guide seems at most a fond memory. At the conclusion of the film, he explains his understanding of his life:

I don’t know how I would make sense of my aging if I wasn’t a father. It is so basic to the way I think of myself and my temporary place in the world. It’s just as simple as, my father was a kid, and then he was a father, and then he was old, and then he died. And now it’s my turn to be a father, and soon I’ll be old and soon I’ll die, and then it will be my son’s turn and my daughter’s turn.

And when I look at people in their twenties, I think sometimes am I envious of their youth and their healthier bodies and maybe I am, but I really don’t think I am, because it’s their turn to be young.

If they’re lucky, they’ll have a turn to be middle-age, and if I’m lucky, I’ll have a turn to be old. But we all just get one turn at each.

Tichenor, however, has not moved on: indeed, as a text explains earlier in the film, “Except for the six months when he tried to become a dentist, Jim has worked continuously as a river guide since 1973,” and in several instances Moss includes shots of Tichenor on the river during the 1990s. The Same River Twice concludes with Tichenor’s final comments: “Actually, what I’ve realized is what I want to do, and I don’t know if I can do this really for a living, but what I want to do is plant perennials in the fall, trim trees in the winter, mulch in the spring, and water in the summer. It sounds like a possible, attainable goal.” Unlike Wasserman, who is conscious of approaching mortality, Tichenor still sees his life as something beginning, still to be determined.

These two views of experience, of course, are not mutually exclusive, and Moss’s presentation of the two comments as the conclusion of the film suggests that they are interwoven in all our lives. The implication here is that life is in some measure an attempt to effect a balance between the recognition that any given moment in our experience is part of a larger, ongoing development from youth to age within which we deal with our responsibilities to the broader circle of family, society, environment, and the desire to enjoy our momentary incarnation as physical beings in the world, day to day, one day at a time, year round.

All of the now aging Riverdogs reveal one or another form of this balance. Danny Silver seems dedicated to enjoying music and exercise, just as she enjoyed them in 1978—but she is also raising two daughters and wants to raise them well. Cathy Shaw has her responsibilities as mayor of Ashland, as well as a daughter and son to raise, but she is passionate about enjoying the tomatoes from her garden every morning; Jeff Golden, whose earlier married life was focused on his being a mover and shaker in Oregon politics, continues to work at being an accomplished man (early in the film we see him on a book tour for his novel, Forest Blood), even as he works at being a good father to his son and daughter and longs for a partner with whom he can share his daily experience. Even the free spirit Jim Tichenor is, however slowly, carefully creating a home, the very image of stability. And Robb Moss is making a film that he hopes will have a public life and meaning for the audiences that see it, and that will enhance his career as a professor at Harvard—though in order to make The Same River Twice, he has left his professional and family responsibilities behind, at least for a time, to continue (as Tichenor does) to do what he realized he loved doing as a young man: “Growing up, it seemed a perfect life to travel and to make movies.” Indeed, the overall structure of The Same River Twice—its attempt to create a balance between the Riverdogs imagery and the video documentation of the then-current ongoing moment—models this double sensibility.

In my estimation, The Same River Twice is, along with Pincus’s Diaries and McElwee’s Time Indefinite, one of the three masterworks of Cambridge personal documentary. And at least as fully as these other two films, The Same River Twice demonstrates what autobiographical filmmakers have always hoped to accomplish: the aging Riverdogs’ decency, intelligence, and personal accomplishments make them “characters” not only at least as interesting and engaging as those we see in even the best fictional films, but far more believable and often, considerably more worthy of admiration and imitation.

The Same River Twice can also be understood within the broader context of the American visual arts, as a twenty-first century version of Thomas Cole’s four-part painting, The Voyage of Life (1839–40), one of the canonical works of the Hudson River School (figs. 36, 37).17 Like Cole, Moss uses a river journey to represent the experience of a life and, also like Cole, sees the transformation from youth to adulthood as the central action of life’s journey. But as a documentary filmmaker, Moss can do what Cole couldn’t: the painter could only create visual emblems of childhood, youth, manhood, and old age; Moss creates a film experience that provides us entry into the developing lives of real individuals as they navigate the rapids and calms of aging and respond to what they’ve experienced and learned. Cole asks us to understand his representations of what he has come to understand; Moss asks us to make our own deductions about the lives we are witness to.

FIGURES 36 AND 37. Thomas Cole's The Voyage of Life: Youth (1840), oil on canvas, 52½" × 78½"; and The Voyage of Life: Manhood (1840), oil on canvas, 52" × 78"; Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Museum of Art, Utica, New York, 55.106 and 55.107.

It remains to be seen if Moss can successfully overcome a weakness of Cole’s four-part painting; Cole died at forty-nine, and his painting demonstrates that he did not experience the final “age”: the individual in Old Age seems to have no life other than a longing for immortality. Moss has begun shooting footage for another river film, and though he has joked that he might entitle it “The Naked and the Dead,” one can hope that he will face the complexities of old age with his fellow Riverdogs and will find a way of creating another film experience that he, they, and we, can learn from.18