Halifax, Nova Scotia, December 6, 1917, 9:02 a.m.

Able Seaman Bert Griffith and his HMCS Niobe shipmates, having finished breakfast, still had a few minutes to spare until their workday began at nine o’clock. A buzz ran through the ship as word spread that the French vessel involved in a collision a few minutes earlier was on fire. Having been abandoned by her crew, she had drifted ashore, coming to rest against Pier 6, a half-mile to the north. When it looked as if the fire could spread from the ship to the shore, Acting Boatswain Albert Mattison and a six-man detail of men had set off in Niobe’s steam pinnace to see if they could be of any help to the firefighters who were battling the blaze. “A lot of us boys went up on deck to see the sight,” Griffith would report in a letter home. “It didn’t look very bad. There were three pretty loud explosions [and] everyone just imagined that it was oil blowing up.”1

Not everyone aboard HMCS Niobe was watching the show in the harbour. Some members of the depot ship’s crew were already at work. At the stern of the ship, an eight-man crew under the direction of Acting Gunner John Gammon, a thirty-seven-year-old native of Plymouth, England, was preparing concrete foundations for the bed of a new cargo crane.

The naval diving suits the divers wore were hot and cumbersome, weighing as much as eighty pounds each. The outfit included lead boots and packs, which enabled the wearer to descend to the bottom and walk around. Hoses carried air that a manually operated pump pushed into the diver’s “hard hat”—a claustrophobia-inducing metal helmet that resembled a hollowed out cannonball. Tiny portholes provided the diver with what at best was limited visibility. It took four men to power the air pump; two more men monitored the air lines to ensure there were no kinks or blockages.

By nine o’clock on the morning of December 6, two divers from Niobe were already in the icy water. The last thing John Gammon and his crew needed was anything that disrupted their routine. Their work was not for the faint of heart. The margin for error was razor thin. Diving accidents were common, and often they were fatal.

ABLE SEAMAN EDWARD MCCROSSAN watched the fire in the harbour from a prime vantage point at the stern of the cargo ship SS Curaca. The Liverpool-based Curaca was at Halifax’s Pier 8 to take on a load of army horses. The Mont-Blanc, ablaze and adrift, had nudged herself against Pier 6, less than 200 yards to the south of the Curaca. That was so close that McCrossan could feel the searing heat. “All the crew of our ship were standing at the stern watching the fire. I counted at least seven explosions and after each one something would shoot away up in the air and burst. One piece looked to be about two feet square and whirled around as it went up. The chief engineer . . . was standing at my side and as one of the explosions took place, and whatever it was went up in the air, he said, ‘That’s gone a couple of thousand feet, at least.’”2

THE CREW MEMBERS of British cargo ship the SS Picton were also watching the Mont-Blanc burn. The Picton was moored next to the Acadia Sugary Refinery while a crew of about eighty longshoremen emptied her cargo holds of crates of food and explosives; the ship was about to go into dry dock for repairs. The unloading was still under way when the Mont-Blanc drifted ashore on the Halifax side of the harbour. When it did, the heat from the fire was so intense that Francis Carew, the sixty-year-old foreman of the workers aboard the Picton, feared it could set the ship alight or ignite the explosives that were still in the holds. “That’s some hot, boys. We’d better secure those hatch covers before we have a fire!” Carew shouted.

The men set about securing the ship in a race against the clock. But it was a contest they were destined to lose.

SIX-YEAR-OLD JEAN HOLDER and her sister older Doris loved school; Jean was in grade one, her sister in grade three. The two girls leapt out of bed each morning, gobbled breakfast, and dressed hurriedly. By nine o’clock, at latest, they were ready to go. It was a brisk fifteen-minute walk from their Robie Street home to Chebucto School on Chebucto Road. These days, classes began at 9:30 a.m. With coal being in short supply, owing to the war, janitors at Halifax schools were under orders to turn down furnaces at night and then to stoke them back to life in the morning. Older children started school at nine o’clock when the classrooms were still chilly; younger students in the lower grades began classes a half-hour later. Regardless, the Holder girls would never have been late no matter what time classes started.

Chebucto School, with room for 700 students, was the largest and finest primary school in Halifax. Two storeys tall and built of sturdy red brick in the Classical Revival–style that was so popular at the time, the edifice was—and remains—a local landmark. “The swarm of people into Halifax for war work soon crowded all the schools, and at Chebucto even the great auditorium was filled with makeshift desks and screens to provide extra classes for junior grades.”3 Erected in 1910 in the emerging suburbs just west of the Richmond neighbourhood, Chebucto School met the needs of the young, upwardly mobile families who were flocking to this area of the city. George and Alice Holder were typical of them.

Thirty-year-old Alice was Irish born. Her husband, George, thirty-three and a native of Halifax, was a chartered accountant. The couple had married in 1908, and by 1917, they had six children, all of them under age eight. Despite his family responsibilities, George Holder was also a patriot and a man of principle. When the war began in 1914, he rallied to the cause, joining the army. Appointed to the rank of sergeant major, he was stationed with the 63rd Halifax Rifles on McNabs Island. Holder was obliged to sleep most weeknights in the barracks; however, the night of December 5 was an exception. “There was to be a military funeral on Thursday afternoon and Dad was in charge of the burial party,” Jean Holder would recall years later. “As he had a wife and family living in Halifax, he was granted leave to sleep at home on Wednesday night.”4

So it happened that on the morning of December 6, George Holder was at home when his daughters were getting ready for school. At nine o’clock, he accompanied the girls to the door. There they kissed their father good-bye before stepping out into the sunshine. At that moment, the Holder sisters had no idea that, like so many of their classmates, they would not attend school that day. Nor would they return to Chebucto School for many weeks.

COMMANDER EVAN WYATT, the CXO for the port of Halifax, was late for work. Most days, he was at his desk aboard HMCS Niobe by 7:30 a.m. Not today. Wyatt was more than an hour late, but even so, he felt chipper. Wyatt and his wife, Dorothy, had attended a wedding reception the night before. It had been an enjoyable night out. These days Wyatt welcomed any opportunity to get away from the hassles and pressure of his job, even if for only a few hours.

When he was not on duty, the CXO was perpetually on call. “My office hours are twenty-four out of twenty-four,” he complained. “I’m never off the end of the telephone. I get down about 7:30 or 8 [a.m.], and [I] leave at 10 or 11 [p.m.] at night; never before 6:30 [p.m.], this is when I get off.”5 When he was not at his desk, he was at home with his wife.

As if the constant demands on Wyatt and his time were not bad enough, he was perpetually at odds with the people he had to deal with each day: Halifax’s harbour pilots, his haughty erstwhile Royal Navy colleagues, and his superior officer Captain Edward Martin—whom Wyatt felt did not respect him or support him in his work. Regardless, the commander was in a buoyant mood as he walked to work on the morning of December 6.

Wyatt was accustomed to receiving work-related phone calls at all hours, but today there had been none to interrupt his breakfast or morning routine. Wyatt had no way of knowing that the phone calls, frantic and fearful, had started not long after he had left on his walk to work. As far as Wyatt knew, all was right with the world. However, as he neared the north gate of the Naval Dockyard, Wyatt could hear the distant clanging of fire alarm bells. He also saw the ominous cloud of black smoke that darkened the northern sky. He wondered what was burning. He would make inquiries when he got to his office.

Wyatt was crossing the railway tracks in front of the Naval Dockyard gates when one of his assistants came rushing out to meet him. Mate Roland Iceton was breathless. He had worked the overnight shift in the CXO’s office, and an hour or so earlier he had stood on the deck of Niobe and watched the French munitions ship the SS Mont-Blanc as she steamed northward toward Bedford Basin. Back at his desk, Iceton dutifully recorded this information in preparation for the nine o’clock end of his shift. His plans changed abruptly the moment he learned the Mont-Blanc had been involved in a collision in the Narrows and was on fire and adrift in the harbour. Iceton knew, all too well, what the French ship was carrying. Panic was already welling up inside him when he rang Commander Wyatt’s home.

“I’m sorry,” the Wyatts’ housekeeper had informed Iceton. “The commander has left for the office.”

Iceton spent the next twenty minutes pacing and worrying. When he finally spotted Wyatt striding down Russell Street, he sprinted out to meet him. Iceton blurted out what he knew about the fire aboard the Mont-Blanc. As he listened, Wyatt’s anxiety level grew. Like Iceton, the commander was well aware of the gravity of the situation. He also knew he had just one boat with firefighting equipment at his disposal. “My one thought was to get hold of the [W.H.] Lee to get down there,” he said.

Hoping to find the naval motorboat there, the commander ran to the coaling wharf that was located just south of HMCS Niobe. Wyatt cussed when he saw that the boat was on the opposite side of the slip. However, seeing that the Lee’s crew were already preparing to go battle the fire, the CXO called out to alert them that he wanted to go with them. He had no way of knowing it yet, but it was already too late to do anything to fight the fire.

AS COMMANADER WYATT WAITED for the W.H. Lee to head out, a half-mile to the north, Lieutenant James Murray aboard the tugboat Hilford had reached Pier 9. Kippers forgotten, Murray leapt the last few feet of water and hit the wharf running. He was desperate to reach the telephone in his office so he could sound the alarm. He knew that evacuating the entire area around Pier 6 as quickly as possible was the only way to avoid massive civilian casualties. The belief that he did not have a moment to spare would be the last thing James Murray would ever know.

LIKE SO MANY OTHER North End residents, Elizabeth Fraser was unaware of the emergency in the harbour. Not that she would have cared even if she had been told about it. She had other priorities. At age sixteen, Elizabeth was already working for a living, and she had a lot on her mind. There was nothing unusual about that, not for a young woman from a blue-collar family in 1917. Universities in Atlantic Canada were among the first in North America to admit co-eds, but most young women in Canada’s Atlantic provinces left school after grade eight and married or went to work; only a minority attended high school. Even fewer young women went on to university; almost all of those who did were from well-to-do families.

In the decade between 1901 and 1911, the number of working women in Canada increased by fifty per cent. Women were paid just half of what males earned, prompting the National Council of Women of Canada in 1907 to adopt a resolution calling for “equal pay for equal work.” That initiative still has a familiar ring to it.

“Owing to the prevailing ideology of separate spheres for men and women, of the male breadwinner and of woman’s place in the home, it was mostly single women who held jobs in the prewar years; other women who took paid work were considered ‘unfortunates’—widows, divorcées, deserted or separated women or wives of the unemployed.”6

With the outbreak of war in 1914, many able-bodied men joined the military. To make up for the labour shortage, a growing number of women went out to work. “Most of the women who worked during the war were unmarried. . . . Despite the movement of women into a few new areas of the economy, domestic service remained the most common female occupation.”7

That was true for Elizabeth Fraser, the second eldest of the seven children of Maude Fraser and her husband Arthur, an iron mold maker. With money being tight at home, she had left school in September 1914 at age thirteen to go to work in the Dominion Textile Factory. The money she earned helped support her family and allowed Elizabeth to feel she was doing her bit “for King and Country.” After three years of making cloth for military uniforms, however, Elizabeth was ready for a change. So she took a job as a domestic helper, working for a young couple with four children, aged ten, eight, six, and three days old.

The morning of December 6 having dawned fair and mild, their mother had taken them out of the house for a few hours, and so Elizabeth planned to do some laundry. “But first the water had to be heated on the stove. This gave me time to start my dinner. Today, I was going to make a stew, and I was at the sink preparing the vegetables when it happened.”8

THREE BLOCKS EAST of the Gottingen Street house where Elizabeth Fraser was busy with household chores, forty-five-year-old Vincent Coleman was at his desk in the rail yard of the Canadian Government Railways. Most Haligonians still referred to the utility as the Intercolonial Railway, as it had been known up until 1916, or colloquially as “the ICR.”

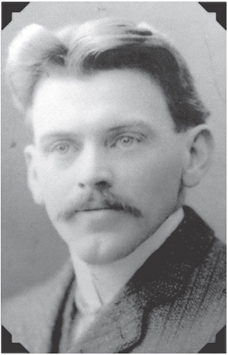

Coleman was a familiar figure at the rail yard. A train dispatcher, he was also a devoted union man with an abiding sense of duty to his job and his workmates. Mustachioed, with a thick thatch of wavy hair, angular cheekbones, and a distinctive cleft chin, Coleman was still handsome at age forty-five for he was careful about his appearance.9 He and his wife, Frances, were the parents of four children: the eldest was thirteen, the youngest one. All the children knew what their daddy did for a living; the Colemans lived at 31 Russell Street, a block west of the train tracks, five blocks south of the ICR rail yard, and a like distance from the North Street Station, the city’s grand red-brick passenger terminal. The sounds of train whistles and shunting rail cars coupling and uncoupling were the soundtrack of everyday life in the Coleman household. Vincent Coleman set his watch by the arrival of the overnight express train No. 10 from Saint John, New Brunswick, which pulled into the North Street Station each morning at 8:55 a.m. Most days, Coleman was at work by then.

His office was a wooden shack located on the west side of the rail yard. If there were no trains parked on nearby sidings, Coleman had a clear view of Halifax harbour. Straight ahead, fifty yards distant, was a huge nautical freight complex made up of Piers 7, 8, and 9, while if Coleman looked to his right, he could see Pier 6, 100 yards to the south.

Vince Coleman used his telegraph key to coordinate the comings and goings of Halifax train traffic. Each day, those trains carried thousands of passengers to and from the North Street Station, delivered freight to Halifax’s busy wharves, and carried troops embarking for the battlefields of Western Europe, as well as the thousands of men who came home wounded and broken. Vince Coleman’s job was busy, and it was vital to the smooth and safe operation of the port.

TELEGRAPH OPERATOR VINCENT COLEMAN. (NOVA SCOTIA ARCHIVES)

On the morning of December 6, Coleman was exchanging information with the night dispatcher when their conversation was interrupted by the sound of a muffled thud that seemed to come somewhere to the south. Both men wondered what had happened. Then, a minute or two later, came the screeching sound of metal grinding on metal. Whatever was going on, Vince Coleman knew it was nothing good. The huge billowing cloud of black smoke in the southeast sky soon affirmed that suspicion. Not long afterward, a co-worker poked his head in the door and advised Vince Coleman and the night dispatcher that two ships had collided in the Narrows, and one of them was now on fire. Coleman was still discussing this news a few minutes later with his boss, William Lovett, the Richmond rail yard’s chief clerk, when a red-faced sailor in an RCN uniform appeared at the office door.

“Boys, you’ve got to get out of here. Run for it, right now!” the sailor shouted. “There’s been a bad accident. A French munitions ship is on fire. The crew have abandoned her, an’ she’s adrift. She’s up against Pier 6 and is going t’ blow sky-high any second.”

Coleman and Lovett stared at one another in disbelief. Then they quickly pulled on their coats. Lovett snatched up the telephone and called a terminal agent he dealt with to warn him of the danger. That done, both he and Coleman moved toward the door. But Coleman stopped and turned back to his desk. He had just remembered that passenger train No. 10, the overnighter from Saint John, chanced to be a few minutes late and would reach Halifax at any time. There might be as many as 300 people on board that train, and Coleman knew the track it would pass along was right next to Pier 6 and the French ship that was on fire there.

“For Chrissakes, Vince! What are you doin’?” Bill Lovett cried. “You heard the man. We’ve got t’ get out of here right now, or we’re as good as dead.”

“You go, Bill. I’ll be right behind you. I’ve got to send a quick message to Rockingham Station. The overnight train from Saint John is due here any minute. I’ve got to warn the crew, tell them to stay back.”

Lovett gave no reply. He was gone in a wink, racing across the rail yard toward Campbell Road and whatever cover he could find there. Vince Coleman was too busy to watch him go. His heart was pounding as he sat down at his desk and began tapping away on his telegraph key. The dots and dashes of the Morse code message he sent to Rockingham Station, four miles to the north, read: “Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbour making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye boys.”10