“A SOUND FOR GOD TO MAKE, NOT MAN”

Halifax Harbour, December 6, 1917, 9:04 a.m.

The hands of the Citadel Hill clock read 9:04 a.m. That was the exact moment of the great Halifax harbour explosion of 1917, which was destined to be the deadliest disaster in Canadian history. A primitive seismometer located in the basement of the old physics building at Dalhousie University recorded the event. However, the dispassionate scientific data—a few squiggly lines scratched on graph paper by a machine more than two miles from ground zero—told nothing of the human story of that fateful day: fear, horror, heartbreak, and drama.

The blast that obliterated the Mont-Blanc, claimed more than 2,000 lives, and devastated the city of Halifax was the most powerful “man-made” explosion in history, a distinction it held until the dropping of atomic bombs on Japan in 1945. Its reverberations shot through the soil, granite, and Precambrian slate bedrock beneath Halifax at a speed of more than four miles per second. That is twenty-three times the speed of sound.

The thunderclap that accompanied the explosion echoed up and down the length of the harbour channel. It boomed across the cities of Halifax and neighbouring Dartmouth, and it was audible much farther away.

The crew of the American cruiser the USS Tacoma heard the boom fifty miles out to sea. The warship’s lookout had just sighted on the horizon the Devil’s Island lighthouse, twelve miles southeast of the entrance to Halifax harbour. “At 9:05 heard heavy explosion in general direction of Halifax, observed great clouds of smoke high in air,” the officer on watch recorded in the ship’s logbook.1

The same rumble that drew the attention of the Tacoma’s crew was audible as far away as Cape Breton Island, 170 miles to the north. In Truro, 60 miles west of Halifax, the blast’s concussive shock broke some windows and shook a clock off the wall in the railway dispatcher’s office.2 As one observer said, the rumble of the Halifax explosion was “a sound for God to make, not man.”3

THE EXPLOSION CLOUD. (COURTESY OF ANN FOREMAN)

THE GREAT HALIFAX HARBOUR explosion of 1917 unleashed the energy equivalent of three kilotons of TNT. When detonated, a single kilogram of TNT releases a million calories of heat energy. Kilo being the Greek word for “a thousand,” it follows that the calories of heat released in the explosion of one kiloton of TNT is a thousand times a million. A billion calories.

The destructive power of a shock wave as intense as the one the Halifax harbour explosion generated is terrifying. On a bright, sunlit day, it is invisible, yet it can send human bodies and objects as big as a house flying like dry leaves in a gale. It can crush a person’s internal organs, rupture eyeballs, and shatter eardrums. It can snap trees, lampposts, and telephone poles. It can level buildings that are close to ground zero, while those farther away that remain upright still see their doors blown off their hinges, roofs destroyed, and windows shattered; glass shards from broken windows fly like tiny arrows that maim, blind, and kill as they sever heads and limbs.

The pressure generated by the chemical reaction in the Mont-Blanc’s cargo hold amounted to thousands of “earth atmospheres”—the 14.70 pounds per square inch (psi) air pressure that is normal at sea level. (By comparison, the pressure at the wreck site of the Titanic, 2.5 miles deep, is about 6,500 psi.) At the same time, the air temperature flared to 9,000 degrees Fahrenheit (about 5,000 degrees Celsius), which is almost as hot as the surface of the sun, and was hot enough to vaporize the Mont-Blanc.

Just as a stone dropping into the still waters of a pond creates rings of disturbance, the destructive shock wave of the explosion surged outward for a mile in all directions and launched skyward molten remnants of the ship’s hull and its cargo. Some bits of this shrapnel were as large as a refrigerator; others were the size of marbles. All were lethal, ripping into human flesh, slamming into wooden buildings, or perforating metal ships.

A piece of the Mont-Blanc’s 1,100-pound anchor soared through the air for two and a half miles before it crashed through a roof. The ship’s 90-mm aft deck gun ended up near a small lake on the Dartmouth side of the harbour, three miles from ground zero. A large chunk of metal from one of the Mont-Blanc’s boilers smashed into the Royal Naval College of Canada, coming to rest in a lecture hall, where it flattened the master’s dais and several student desks. Fortunately, the room was empty at the time.

THE HEAT OF THE EXPLOSION that obliterated the Mont-Blanc superheated the water around and under the ship, gasifying the sea to the harbour floor, twenty feet beneath. As water rushed in to fill the vacuum, it threw up a tsunami. The massive wall of water thirty feet high raced across the harbour to Dartmouth. It also roared up and down the harbour channel and far out into the Atlantic. In the confined space of the harbour, the impact was murderous. The tsunami battered ships, swamped boats, and tossed vessels of all sizes up onto the shore. It dragged people to their deaths when it washed over piers and sped waist-deep along streets on both sides of the harbour. “[The tsunami] boiled over the shore and climbed the [Fort Needham] hill as far as the third cross-street [Albert Street], carrying with it the wreckage of small boats, fragments of fish, and somewhere, lost in the thousands of tons of hissing brine, the bodies of men.”4

Even then, the murderous wave was yet wreaking havoc. On its retreat, the water snatched up still more debris along with the bodies of explosion victims, some alive, others dead. And with them it carried off personal property, vegetation, animals, and the remains of crumpled homes and workplaces. There was still more misery to come.

In the wake of the tsunami’s retreat, a towering cloud of noxious gases that billowed high into the sky drifted over Halifax. “For ten minutes after the explosion a ‘black rain’ was observed to fall from the sky. This was an oily soot, the unconsumed carbon of the explosives. It blackened clothing almost like liquid tar,” recalled Archibald MacMechan, the Dalhousie English professor who would become the “official historian” of the explosion. “It blackened the faces and bodies of all it fell on. . . . It penetrated clothing to the skin and coated the ruins of the houses, until the snow and rain storms washed it away.”5

AT GROUND ZERO in Halifax harbour, along with the Mont-Blanc, the explosion obliterated Pier 6 and Pier 8 and all the buildings on each of them. All disappeared. Aboard the SS Picton, which was moored at Pier 8, supervisor Francis Carew along with his two assistants and sixty-four dock workers and members of the ship’s crew died instantly; fortunately, they had secured the ship’s hatches before the blast and so the munitions in the cargo hold did not explode.

At Pier 6, nine of the ten Halifax firemen who had been battling the fire perished in that same instant. The crew of the Patricia were still positioning their fire hoses while driver Billy Wells was maneuvering the pumper truck to position it close to a fire hydrant when the Mont-Blanc blew up in a blinding flash. The searing fireball that blew outward from the blast’s epicentre incinerated everything and everyone in its vicinity. With one exception.

THE EXPLOSION, WHICH CLAIMED THE LIVES OF CHIEF CONDON AND EIGHT OF HIS MEN, ALSO DESTROYED THE PATRICIA (LEFT) AND THE CHIEF’S 1911 MCLAUGHLIN ROADSTER (BELOW). (COURTESY OF TREVOR ADAMS/HALIFAX MAGAZINE)

At the instant the explosion occurred, Billy Wells had been sitting in the driver’s seat of the Patricia, his hands on the steering wheel. The next thing he knew, he was standing fifty yards from where Pier 6 had been, and he was naked. The blast had torn off his clothing, along with most of the flesh on his right arm. Although he felt no pain, the bones were exposed. In his left hand, Wells still clutched half of the Patricia’s steering wheel.

When he looked around for the fire truck and his mates, Billy saw nothing. They were all gone. But he had no time to make sense of any of this because in the next instant, the tsunami, a roiling wall of water thirty feet high, swept over him and carried him off.

It was a miracle that the wave did not claim Billy Wells’ life. It was not his time to die. When he regained consciousness, he staggered westward, through the ruins of the rail yard and into what had been the Richmond neighbourhood. The damage and the carnage he saw all around him were nightmarish and horrifying. “[I] made my way to . . . Campbell Road. . . . The sight was awful . . . with people hanging out of windows dead. Some with their heads off and some [bodies] thrown over the overhead telegraph wires.”6

THE SHOCK WAVE GENERATED by the explosion in Halifax harbour cut a 325-acre swatch across Halifax’s North End. “People inside buildings during the blast endured one horror after another: shooting glass, tumbling ceilings and walls, [and] crashing furniture. With incredible speed, fire also added to the deadly work of the explosion.”7

Its effects were most acute on the east-facing slope of Fort Needham hill, which overlooked ground zero. There the explosion levelled houses, shops, factories, and businesses.

All the workers who had climbed up to the roof of the Acadia Sugar Refinery for a bird’s-eye view of the fire at Pier 6 perished when “the massive brick walls . . . collapsed like a house of cards,” as the Halifax Herald reported.8 Twenty-seven children and the matron of the nearby Protestant Orphanage suffered a similar fate.

Meanwhile, 120 workers at the Naval Dockyard, as well as shopkeeper Constant Upham and the customers who had congregated outside his business, all died instantly.

A few blocks to the north, the blast cut down dozens of onlookers who were standing on a pedestrian bridge that spanned the Richmond rail yards at the foot of Duffus Street, 300 yards from Pier 6.

The Hillis and Sons Foundry, across the street from the Hinch family’s home at 66 Veith Street, felt the full fury of the blast. The building crumpled, claiming forty-one victims; the foundry’s manager, Frank Hillis Sr., and his son James, the assistant manager, were among them.

Sixty people perished at North Street Station, Halifax’s main railway passenger terminal, when steel girders, concrete, and glass in the roof crashed down onto the platforms and tracks. “The station, a fine building with a glass dome, now stood open to the sky.”9

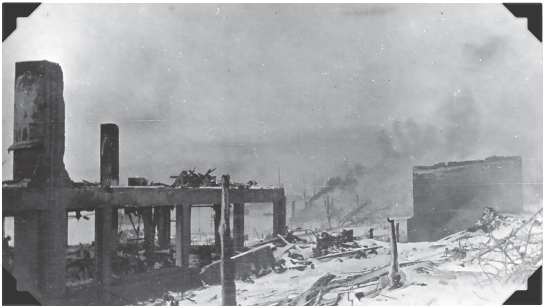

THE RUINS OF THE HILLIS FOUNDRY, WHICH STOOD ACROSS THE STREET FROM THE HINCH FAMILY’S HOME ON ROOME STREET. (COURTESY OF ANN FOREMAN)

Damage at the nearby Richmond railway yard was also extensive. Train dispatcher Vince Coleman, who had remained at his post to send that one final telegram to warn off the No. 10 overnight passenger train from Saint John, died instantly. His boss, William Lovett, who had fled the rail yard moments before the explosion, was also among the more than fifty railway workers who perished.

THE RUINS OF NORTH STREET STATION, WHERE SIXTY PEOPLE PERISHED WHEN THE EXPLOSION COLLAPSED THE ROOF. (UNDERWOOD AND UNDERWOOD, NY)

All told, the great Halifax harbour explosion of 1917 destroyed more than 1,500 buildings and damaged 12,000 more. Six thousand Haligonians suddenly found themselves homeless, while more than 25,000 lacked adequate shelter. Almost 2,000 people in Halifax and surrounding areas would lose their lives, with hundreds of them perishing in less time than it takes for a single heartbeat.10 The numbers are staggering. But numbers do not tell the full story of the agony, suffering, death, heroism, and incredible human courage of the people of Halifax and of those volunteers who came from far and wide to help with the emergency relief efforts and to help rebuild.

In the hours, days, and weeks after the disaster, many of those who had suffered grievous injuries in the blast died. Each of them left behind loved ones—family and friends—and unfulfilled hopes, dreams, and potential. There was also a tragic story behind every person who died so unexpectedly and so tragically.

Every survivor had a story of heartbreak, suffering, and loss to tell; all would recall the horrors they and their loved ones had endured. However, the story of the great Halifax harbour explosion of 1917 is, above all, a story of courage, perseverance, and the resilience of the human spirit. The people of Halifax endured unspeakable pain, yet they and their city emerged phoenix-like from the disaster to heal and rebuild their shattered lives and their city.

FEW OF THE PEOPLE who actually witnessed the great Halifax harbour explosion lived to tell the tale. Able Seaman Bert Griffith, aboard HMCS Niobe, was one of that select group.

Griffith and his mates were standing on the deck of the RCN’s depot ship in the moments just before the blast. The thick pall of black smoke that hung over the water stung the eyes and made onlookers cough. It was akin to peering through a pane of smoked glass, but even though the fire was a half-mile to the north, the flames engulfing the Mont-Blanc were a sight to see. “All at once there was a most hideous noise [and] I saw the whole boat vanish, a moment after I saw something coming. [I] can’t describe it,” Griffith would recount in a letter home written a few days later.11

Charles Duggan Jr. was another eyewitness to the explosion. He made his living operating a nautical taxi service that catered to dockyard workers. Having dropped off his passengers and completed his early morning runs, the twenty-year-old had been back home having breakfast. Duggan, his eighteen-year-old wife, Rita, and their four-month-old son, Warren, lived with Charlie’s parents and his siblings in a wood-frame house at 1329 Barrington Street. The Duggans were one of the many big, closely knit Irish Catholic families in Halifax’s bustling North End. More than two dozen members of the extended Duggan family called the Richmond neighbourhood home.

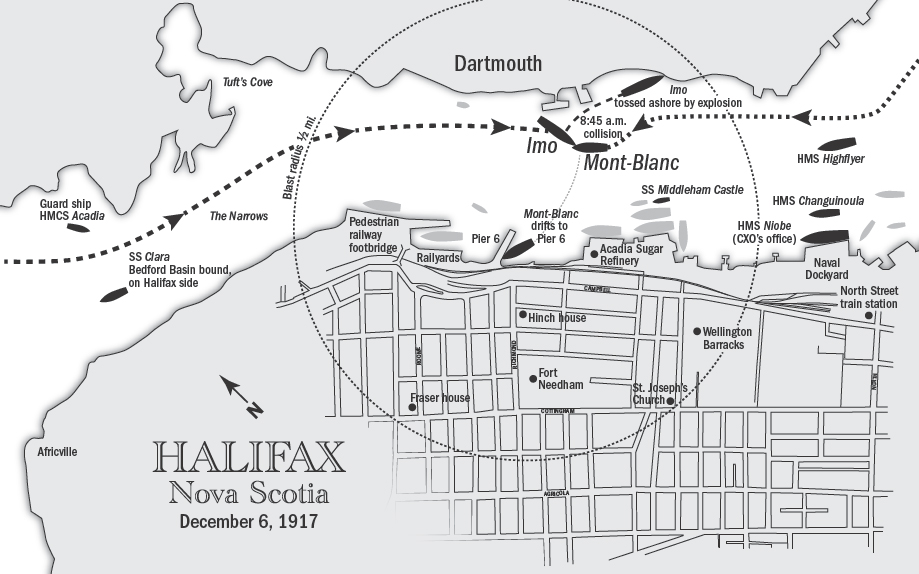

Maps by Larry Harris.

The moment Charlie Duggan learned that two ships had collided in the harbour, he grabbed his hat and coat and ran out the door. After sprinting down Hanover Street, he crossed the railway tracks and reached the dock where he kept his thirty-six-foot trawler, the Grace Darling. With the boat’s engine racing all out, Duggan sped toward the Mont-Blanc and the Imo. He was intent on helping in rescue efforts. “Before I had got halfway to the French boat, her deck had caught fire and the men of her crew were spilling over the side like rats,” Duggan would recall.12 The Frenchmen were madly rowing their two lifeboats toward Dartmouth, and Duggan instantly understood why; smoke from the fire clouded the air, stinging the eyes and searing the lungs when breathed in.

The heat from the fire and the booming explosions that periodically echoed across the harbour prompted Charlie Duggan to turn his boat and race for home. He was about to do so when curiosity got the better of him; he paused to take one final look at the burning ship. What he saw was mesmerizing. The flames were multi-hued and hissed as they burned.

Duggan was not alone in his fascination with the fire. The men aboard the Stella Maris and other boats that had been battling the blaze were similarly awestruck. Uncertain of what they were dealing with and increasingly wary of whatever dangers they were facing, the men had backed off while struggling to decide whether to resume the fight or flee.

The scene in Halifax harbour was surreal. The water in the harbour was placid. The sun continued to shine in a cloudless blue sky. That miasmic fog of oily, acrid smoke fouled the air. Yet an eerie calm prevailed. Was this the proverbial calm before the storm? That thought occurred to Charlie Duggan.

A bolt of fear, visceral and urgent, prickled the hair on the back of Duggan’s neck and set his knees quivering. Call it premonition. Call it dread. But in that instant he sensed that he had to get as far away from that burning ship as possible, as quickly as he could. If he did not, he somehow knew he would die. “I bent over the engine trying to coax a little extra speed out of my boat and must have been half way across the harbour toward the Dartmouth side when the ‘thing’ occurred. I say ‘thing’ because I shall never find words to express what next happened.

“I was standing in the boat looking backward toward the Mont-Blanc when she appeared to settle in the water. A lurid yellowish-green spurt of flame rose toward the heavens and drove ahead of it a cloud of smoke, which must have risen 200 feet in the air. Then came the most appalling crash I have ever heard, and my boat went under my feet as if some supernatural power had stolen her from me while I myself was thrown into the harbour.”13