Singing a Māori-haka-meets-Liza-Minnelli version of ‘New York, New York’ in Tribal Hollywood at the Edinburgh Fringe, 1999.

CHAPTER ONE

WEET-BIX MĀORI

But the queer – not yet gay – world was an even more intimidating area of this hall of mirrors. I knew that I was in the hall and present at this company – but the mirrors threw back only brief and distorted fragments of myself.

— James Baldwin, ‘Here Be Dragons’

I used to believe that my birth mother gave me away without a second thought, but that wasn’t true. I only found out forty years later. My birth sister tracked me down and told me the real story. When I was born, my mother told the hospital that she wanted to keep me, but they wouldn’t let her. They took me away before she could even see me. Turns out, at the time when I was born, it was not unusual for single Pākehā women who had babies with Māori men to be forced to give their babies up for adoption. I’ve met two other men who were also taken at birth, handed to nice middle-class, Pākehā families in the same way. We’re New Zealand’s own ‘Stolen Generation’.

— Mika

THE ONE, THE ONLY . . . MEEEE-KA!

A few years ago, I took a road trip to the port town of Timaru, several hours to the south of my home in Christchurch. Our destination was Timaru Boys’ High School, a bastion of middle-class culture for the (male) descendants of New Zealand’s early settlers. We were there to see the Māori performance artist Mika, an ‘old boy’, perform his cabaret show. The gymnasium/auditorium was lit mostly by votive candles on low tables that were scattered, cabaret-style, around a cleared space on the floor. Overhead was a mirror ball, casting diffused glints of light at the basketball hoops and commemorative plaques and on us. At the grand piano in one corner, a man sat playing a mix of classical and contemporary tunes; in the opposite corner a large TV screen was soundlessly cycling through highlights from Mika’s TV series, Te Mika Show.1 The room filled quickly around us: mostly older Pākehā (white, non-Māori) men and women,2 who greeted each other as if at a high school reunion – which is what it was in many ways. They purchased glasses of wine, beer or soda, nibbled on rice crackers and dip, and chattered amongst themselves in cosy companionship.

At 7.30 p.m. sharp, the pianist stopped. Recorded music swelled. From behind the curtain Mika announced himself over the PA: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, performing here for you tonight, it’s the one, the only . . . Meeee-ka!’ And then he entered to ecstatic applause. A cluster of feathers topped his hair, and he wore an enormous black patterned cloak (by Issey Miyake) that he dramatically swished to make a peepshow of covering and revealing a loincloth festooned with pāua shells and yellow straw – a creation of the Pacific Sisters performance art collective. He spent the next hour in the spotlight under the spinning mirror ball, singing medleys that slammed traditional Māori tunes and phrases into songs by Madonna, Prince and – for the encore – Roberta Flack, dancing, joking and reminiscing with the audience about how he felt to be back where, so many years ago, he had been so well known as Neil Gudsell, at once the only visibly Māori and the only openly gay boy in the school. His adopted sister and his birth sister were sitting together in the front row, along with his old teachers and former schoolmates. After the performance, he changed into a kaftan that was adorned with cameos of the Virgin Mary; then he posed for photos, his arms around clusters of adoring fans. He was, after all, a celebrity – an old boy who had made it big on the international stage, returning in triumph to the town where it all began.

All this is to say that it was a very strange evening. All the more strange because I seemed to be the only one who thought it so as I watched this native New Zealander, this gay Māori man, spin bits and pieces of Māori language and cultural performance into songs from the international hit parade. It was a kind of ‘native drag’, at once ambivalent (in attitude) and ambi-valent (in motion), a queer tipping into and slipping between the tropes of postcoloniality and biculturalism, dressing up and discarding each in turn.

A WEE BROWN FACE IN A SEE [SIC] OF WHITE FOLK

Who is Mika? Proudly, performatively Māori. Just as proudly and performatively gay. Mika grew up in Timaru, as he says in his performances, a queer brown boy adopted into a resolutely white, straight home, discouraged from seeking out his birth family who, he discovered only much later, were living just a few doors away. Mika’s childhood experience of self calls to mind the hall of mirrors James Baldwin describes in ‘Here Be Dragons’,3 or as Mika sometimes says, ‘here be taniwha’ – taniwha being a Māori equivalent to the European concept of dragon, or sea monster, the awe-full apparition at world’s edge.

Families are our first mirrors; we look to them to find out who we are, who we might become, mostly by aligning ourselves with what we see. Sometimes, however, it’s not so simple. From the start, Mika, in looking to his family to find himself reflected, saw instead prismatic refractions – not the singularity of sameness but the bits and pieces of difference, of Other-ness.4 Embraced by the family who took him in, he embraced in turn his shifting sense of self as something to be discovered, experimented with and performed for others. And as he has gone along, his celebration of a different sort of self-in-the-making has inspired him to celebrate others for their differences. It’s made him the celebrity we see today.

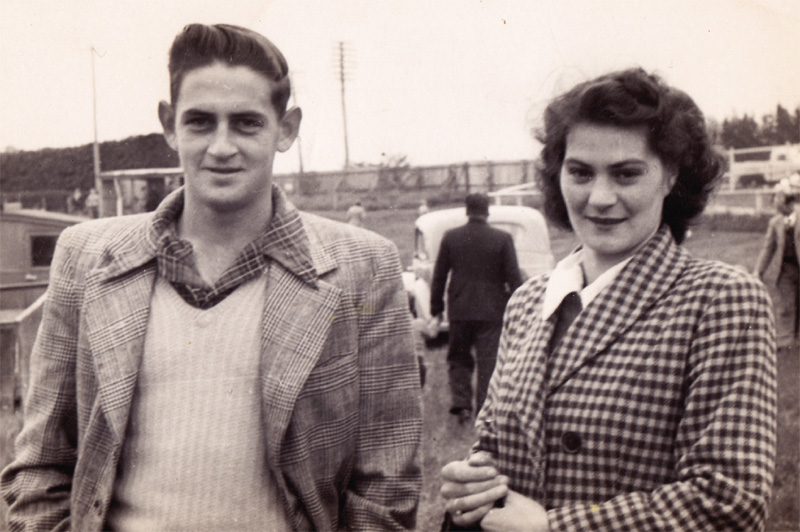

In an early family photo we see him with his older sister and parents, just about to dance himself out of his frilly baby clothes. Neil Gudsell. Mika before he was Mika. He’s not at all camera-shy, flirting with the lens (and whoever is behind it) already: chubby-cheeked and cheeky, looking as though he’s just told himself a little joke. With the floral drapes and blinds setting the stage, this could be just about any nice, middle-class-ish family portrait, taken from anywhere in the Western world: ‘a vision of ordered, comfortable domesticity’ perfectly reflecting New Zealand’s ‘post-war suburban idyll’.5 It’s the early 1960s, the tail end of the baby boom, the last lull before the incursion of popular culture via television and radio stirred things up. Mika’s parents look old enough to remember the war, yet young enough to move to the new beats.

Mika, aged eighteen months, his parents Dawn and Bill Gudsell and his sister Shirley in the family’s state house at 24 Tweedy Street, Timaru, c. 1963.

The family photo is also quintessentially Timaru – from Te Maru (meaning ‘place of shelter’) – where (as I write this) the mayor has just declared war on the rest of Southland for the cheese roll title.6 As a convenient stopover on the drive between Christchurch and Dunedin, Timaru can seem to the casual traveller like the land that time forgot. A beautiful ocean view, with a summer carnival on the waterfront. Pubs, cafés and tearooms set into preserved colonial buildings. An assortment of shops and a couple of petrol stations on, or just off, the main street. Writing to Mika in 2012 of her memories of the town and time, Sue Schuster remembers Timaru as ‘[j]ust a small, quiet, slow moving town. Keep in line, don’t rock the boat.’7 In Growing Up Gay, Mika describes it as ‘the closest thing to the town in Twin Peaks, in that it looks utterly conventional but contains pockets of the bizarre’.8 Indeed, on the grounds of Timaru Boys’ High, near the auditorium where I saw Mika perform in 2010, there grows a Black Forest oak tree – presented by Adolf Hitler to Jack Lovelock as a symbol of Germany after his gold medal win in the 1936 Olympics.9

Mika’s mother and father courting in the 1950s.

Mika’s father aged sixteen, dressed up and posing with a penny-farthing in South Canterbury.

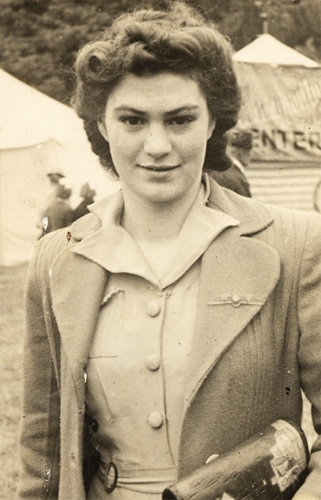

Mika’s mother aged sixteen just after World War II, March 1946.

New Zealand in the 1960s was, at least on the surface, a thoroughly settled place. It was still colonial, only tangentially connected to the wider world – mostly via the provision of lamb, butter, and army fodder – and, superficially, not much more progressed since it was imagined in Green Dolphin Street (1947), the first Hollywood film to feature New Zealand scenery and peoples in a quasi- (very quasi) realistic manner. In Green Dolphin Street, we see the settler-protagonists (played by Van Heflin, Richard Hart and Lana Turner) survive a spectacular earthquake and a vividly violent betrayal by their Māori workers – including a remarkable, for all the wrong reasons, performance of the haka ‘Ka Mate’ (by a mélange of non-white, non-Māori actors) – to land at last in Dunedin in the late 1840s. The final scene shows them in a domestic tableau, comfortably seated at a formal dinner, looking forward to making their fortunes raising sheep, on the top of the world at its bottom end, the Māori successfully relegated to background colour. Change the hoop skirts for twinsets, I imagine, and the South Canterbury scene might look much the same a century later: sentimentally settled, modestly prosperous and superficially homogeneous.

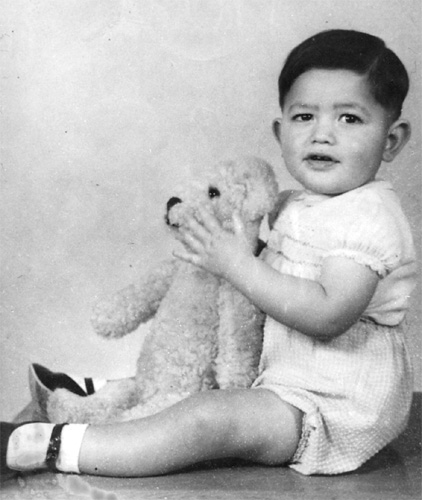

How unsettling then to be Mika. Precociously self-aware, even as a child, he says, ‘I’ve always been queer. Always.’10 His first sexual encounter, he claims, was with a boy when he was around four years old – or maybe eight, he adds, depending on how ‘sexual encounter’ is defined. While his coming out, at age twelve or thirteen, was met with repressive force in some quarters, even violence, when push came to shove he held his own. In his baby photos, whether formally posed in the studio or captured au naturel in the family paddling pool, he looks extraordinarily self-possessed.

His baby pictures and school photos are perfectly ordinary, of course. What we know now of Mika almost certainly colours what we see in these images of the past: a glint in the eye, a sureness in the way he holds his body and poise in his pose for the camera. That the boy in the photos could be any boy, almost anywhere, that his image is so like anyone else’s, and yet it is not, is somehow significant, critical to the way we respond to the grown man now. Perhaps this is because in seeing the twists and turns of apparently contradictory identity positions – butch and femme, Māori and Pākehā – successfully intertwined in Mika’s performance of self, we experience our desires to be something more than ordinary in our own selves.

Mika’s desire to find himself as Māori, like his desire for sex with other men, seems to have been hardwired into him from birth. Before he was Neil Gudsell, for a brief few days, he was Terence John Pou. He was born in 1962 to a Pākehā mother, Elizabeth Halkett, and traces his whakapapa (heritage) through his Māori father, Witoti Winiki Pou, to Te Kotahitanga Marae in Kaikohe, in the Far North. Almost immediately, he was adopted by the Gudsells – his ‘real family’ (emphasis his), as he puts it in Growing Up Māori (1998), a collection of reminiscences edited by Witi Ihimaera. And here is where the swings and roundabouts of identity in bicultural Aotearoa New Zealand begin to reveal themselves. For a long time, Mika believed that his birth mother had rejected him, suspecting her of not wanting to be a white mother with a brown son. But while his birth father, who was distinctively Māori, and the rest of that side of the family had removed themselves to the north, it turns out that Mika’s birth mother and sister were not so Pākehā after all; they were essentially closeted as Māori living in a predominantly Pākehā town.

Mika’s mother won this Easter egg in a raffle at the Four Square in 1963.

Mika at eighteen months in the family’s paddling pool.

Mika with his teddy, 1963.

The story Mika was told of his birth stayed with him for over forty years, as he recounted with equal parts anger and indifference in Growing Up Māori: ‘I wasn’t born in an alley, I was born in a hospital bed. Born to a woman who gave me away at birth. She never even saw me. As if my being born wasn’t worth even a look in. Now she never will see me I suppose.’ 11 The real story, as he found out only recently, is more complicated, less personal than political – an indictment of the sexual and racial ethos of 1960s New Zealand. What Mika was told, when his birth sister Rosa tracked him down in the early 2000s, was that his mother was not given a choice. According to Rosa, it was down to Dr Burnett, who delivered Elizabeth Halkett’s baby and immediately took him from her. He refused to countenance her attempt to revoke the adoption, and denied her any chance to see or hold her baby. Basically she was told to get over it, to get on with her life. Burnett, who happened to be the Gudsells’ own family doctor, then handed the baby to Dawn and Bill, telling them that the birth parents had moved to Australia.

The doctor’s actions might have been seen at the time to be virtuous – a moral intervention into an otherwise sordid tale. Because of him, a young, apparently Pākehā woman, who had been tainted by having sex with a Māori man, could have her slate wiped clean. She would be de-tarnished, free to marry – even this same Māori man, as she later did – and then, safe in the bonds of wedlock, she could have children properly. Meanwhile, this mixed-race, illegitimate baby boy – like so many others then – could be assimilated into middle-class, white suburban propriety. He too would be de-tarnished, lifted from the shadow of his mother’s shame, whitened. This sort of social engineering, the residue perhaps of earlier governmental policies of ‘pepperpotting’,12 may not have been on the scale of that practised on Australia’s Stolen Generation: Aboriginal children, especially those of mixed race, forcibly removed by from their families and communities during decades of government-driven ethnic cleansing. But it’s one of New Zealand’s guilty secrets, the memories not fully repressed of violence done to children such as Mika, to their mothers and fathers, to the families that took them in and to our society as a whole.

Given the drive to deracinate children like Mika, it is perhaps ironic that his adoptive family also mixed and matched, Māori and Pākehā, in ways that were not quite so straight as they seemed. His mother was of Kāi Tahu and Kāti Māmoe descent, but, in keeping with the place and time, she kept her whakapapa under wraps. The Gudsells claimed celebrity connections on Dawn’s side: to the Fluteys, Fred and Myrtle, in Bluff, who became famous for their shell-clad Pāua House, a tourist attraction that was dismantled in 2009 and reassembled in the Canterbury Museum; and to Lord Anderson, who signed the death warrant for Mary, Queen of Scots.13

Mika at Marchwiel Kindergarten, Timaru, 1965.

Reminiscing from the vantage point of the late 1990s, Mika wrote that ‘if you ask me what it was like for this Māori baby to be raised White, I can only reply, “damn fine”’.14 He recalls that he only discovered the Māori connection ‘when one of the aunties decided she wanted to claim the family land at Akaroa!’ Even then his mum stopped him from ‘playing with poor Māori kids or learning anything Māori’. This wasn’t out of prejudice per se, he says: ‘Not ’cos she didn’t like them – God, she adopted one, and lost friends for doing so! No, she did it ’cos from 1968 to 1978 you still didn’t do Māori things.’ Dawn was not wrong in her assessment of the cultural challenges surrounding her family. Mika says:

When Disney on Ice came to Christchurch, I remember wearing a long white sheet, like a cape, and twirling around the garden singing ‘I’m Snow White, I’m Snow White.’ And my next-door neighbour yelled out ‘no you’re not, you’re Maaaah-ri’. I think at that stage even I was learning hatred of the race – self-hatred – because I remember replying something like, ‘no I’m not.’ But . . . at school, my nickname was Wog. Needless to say, Dawn was not amused.15

Even so, his father, Bill, encouraged him to explore the Māori side of his cultural identity:

One day I asked my mum if I could play with Riki Taikato. Mum replied ‘why do you always have to play with Māori kids?’ I looked at her. Dad butted in, ‘because he is one, Dawn.’ My belief is that my mum, Dawn, was protecting me from the propaganda of the day that said that Māori culture was valueless and would get you nowhere. Oddly enough, it’s taken me everywhere.16

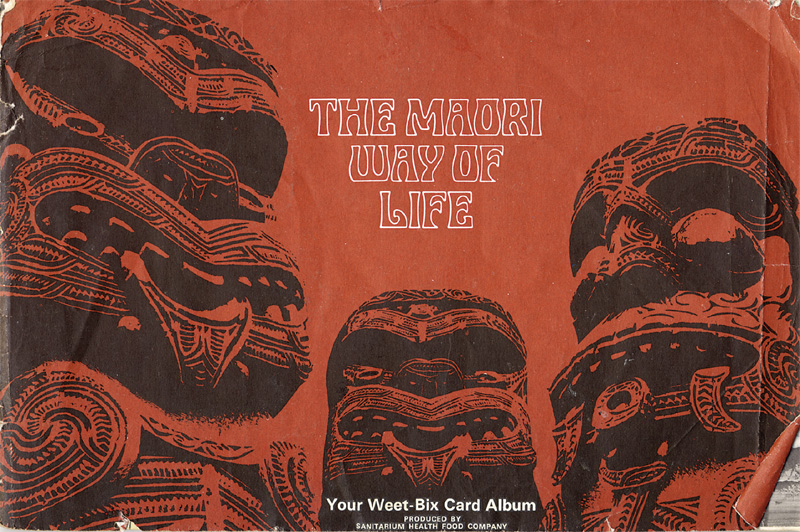

THE MĀORI WAY OF LIFE

In Mika Haka, he tells the audience that ‘because I was forbidden to do anything brown, it allowed me to explore my roots on my own terms . . . a sort of cultural pic-n-mix’.

Lacking both whakapapa and tūrangawaewae (literally ‘a place to stand’ or ancestral homeland), Neil’s search for his missing Māori identity began, oddly enough, through a childhood encounter with a guidebook to Māori culture: ‘The Maori Way of Life’ was produced for a predominantly Pākehā market as a promotional gimmick by the Weet-Bix cereal company – itself an iconic New Zealand brand. ‘The Maori Way of Life: Your Weet-Bix Card Album’ has been preserved by Mika, along with an astonishing array of ephemera from every stage of his development and career.17 This little booklet presents itself to New Zealanders of the 1960s as instructional, in effect offering a touristic view, by and for Pākehā, of the native culture. Each page offers a detail or two about life on the marae, which is made complete only as the child scavenges illustrative cards from cereal boxes and pastes them into the gaps on the illustrated pages.

‘The Maori Way of Life’ – Sanitarium Weet-Bix card album, 1969. Mika calls this ‘a cereal awakening to my Māori culture’.

Mika with his mother Dawn, brother Lindsay, and cousin Brendan Anderson. Mika’s father took the picture during a family holiday in Rotorua in the late 1960s.

Seeing Mika begin the project of piecing together his cultural identity from a marketing gimmick in this way – as an already performative construction, wrought at the meeting place between colonisation and commerce – makes it possible perhaps to understand the way his performances seem continuously to plumb what might be called ‘the depths of the shallows’. But it was more than that. Mika remembers: ‘My mum’s best friend, Kay, was a Pākehā married to Hemi the Māori. Hemi took it upon himself to teach me traditional carving whenever mum wasn’t around. However, he forbade me to learn weaving, because it was for girls. I was not amused.’18 When all else failed, imagination and ingenuity stepped in.

When it came to Māori Day in school, being the only Māori in my class, I was asked if I knew how to do the haka. As I was the kid who always got stuck up to sing at assemblies, I of course said yes, of course I can haka, thinking ‘what the hell is a haka?’ The teacher invited me up to demonstrate. The only words I can remember are: ‘unga unga bunga bunga’. The teacher’s face said it all.19

Hemi Ruwhiu making a hāngī (baking pit) in the late 1960s. Hemi introduced Mika to tikanga (Māori cultural practices) and taught him to carve at a time when Māori identity was suppressed, especially in small South Island towns like Timaru.

Beyond covert carving lessons with Hemi, it seems Mika saw little of himself reflected in anyone around him – ‘a wee brown face in a see [sic] of white folk’.20 Lacking Māori role models in his early years, he has spent his life in this way, inventing his identity in performances that have been seen nationwide and internationally. In New Zealand, as elsewhere, racial and ethnic identifications exist on a continuum, determined as much by performance of self as by colour and other aspects of visibility. Like his costumes, Mika’s performances create a superficial holding pattern, their fabric roughly woven between the indigenous and the imported into a stylish swirl that is hyper-visible without necessarily being transparent, skating the surface of, and reflecting, the cross-cultural cosmopolitanism one finds in contemporary (almost) postcolonial New Zealand. As such, Mika’s nascent identity seems to have been revealed in oblique glimpses and made coherent only by conscious construction after the fact.

A family barbecue with cousins and Pepe the dog, early 1970s. Mika is at front left, in black jersey and lavender shorts.

Mika with his family and a Mormon elder in front of their home at 24 Tweedy Street, 1970s. Throughout Mika’s childhood the family boarded Mormon elders. (This photo was taken by another elder.) Mika remembers the importance of the money earned from boarders: ‘We were the first people on our street to buy our state house, and the first to buy a TV.’

A family summer holiday at Lake Wānaka, 1970s, with cousins from the Solomon and Anderson families. In the back, Mika is wearing red togs and Lindsay is in purple.

Temuka wishing well for foster kids (1972). Mika, Lindsay and Shirley are posing with David and Margaret Thompson, who were among many foster children taken in by the Gudsells over the years.

At the Pāua Shell House in Bluff, 1970s. From left: Dawn; Lindsay; an unnamed member of the Flutey family; Mika with his grandmother, Florence Anderson; Shirley; and Lynley Anderson, a cousin.

Mika’s search for his Māori self is reflected in the way his performances repeatedly reference kapa haka, the Māori performing arts practice that has come to be considered ‘traditional’ even as it mixes aspects of remembered ritual (i.e. from before contact with European settlers) with more contemporary, imported theatricalities and musicalities, including those arising from the long history of Māori performance for tourists.21 Kapa haka is itself a quintessentially postcolonial performance practice; it enacts both the resistance to and the effects of colonisation. We see guitars (and sometimes ukuleles) and often hear tunes stolen from, for example, Prince or Simon and Garfunkel, or from movies like The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert and TV series such as Game of Thrones. The tunes slip from Western harmonies to the different harmonics, the microtonal notes between the notes, of the Māori scale.22 The actions hew to the reconstituted rules of earlier ritual and cultural practices – haka, poi, waiata-ā-ringa, and so on. The words, though, confront issues and conflicts directly in te reo, the Māori language, politicising what might otherwise appear (superficially) as a folkish performance of the natives-humming-and-strumming genre.

A final full family photo, taken in 1976, before Mika’s father died in 1978.

Mika’s haka picks up where kapa haka leaves off, aggressively remixing past and present to a contemporary beat, confronting his diverse audiences in English as well as te reo, and bringing to the surface the underlying erotics of the (post-)colonial encounter.23 There is a kind of adolescent boy energy in all of this. Seeing him in performance, swirling and chanting, singing low and then wafting above his back-up boys (and girls), one sees also again Neil Gudsell, high-school drama queen and sports star – the boy who succeeded at Timaru Boys’ High School by blurring the demarcations of adolescent identity.

South Canterbury Athletics Club prize-giving, 1974.

He recalls coming out in intermediate school: ‘I was a very tall eleven or twelve year old. I was a fast runner, and I also played rugby. So I think a lot of people didn’t believe me when I said I was gay.’ Looking back, he adds, ‘I think I must have been very brave and shocking. Especially on mufti day at Timaru Boys High School, when I wore a silver skin-tight dungaree catsuit and a pink and blue striped polo-necked sweater, accessorised with high-heeled black shiny boots.’ Brave and shocking, indeed. As he remembers it, ‘The closeted gay kids didn’t want to know me. The straight boys wanted to kiss me.’24 Asked if he was a ‘practising homosexual’ he answered, ‘Practising? I’m fully qualified!’ And when it came time to pick a topic for ‘public speaking’, he chose gay rights:

The shock went through the school like you can imagine. I was called to the principal’s office to explain where I got my research. My response was to reach into my bag and pull out Time magazine – of course anything by Time magazine was legitimate. This was the mid-seventies, and it was the issue where the Kinsey report determined that gayness was not a mental illness. The principal was so ok with my explanation that he made me the official disco teacher of the school – an all white, farming boys’ school. I had the perfect recruitment pitch for the boys. I said ‘have you seen me at the disco?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Have you seen me with all sorts of girls?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Would you like a girlfriend?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Then you need to learn to dance.’

Mika representing Canterbury in his first national athletics championship meet, late 1970s. He came ninth in the 400-metre hurdles.

Gay and Māori, yes; a star performer and also a star athlete, the guy girls flocked to and the guy other guys turned to to learn how to get on with girls. Being popular didn’t fully insulate him against the bully boys, but he had plenty of fight in him. He recalls coming across one in the boys’ loo: ‘I pushed him hard against the urinal, so that he splashed himself. Told him I knew how much he wanted me.’ Years later, when he crossed paths with another in the supermarket, he loudly told the man’s wife, ‘Your husband was the best fuck of my life!’ Remarkably, especially for the time and even now, the school had his back. He credits two men in particular who refused to tolerate any bullying of the school’s only visibly gay student: a teacher, Bruce Leadley, and the rector, Mr Walsh.25

It is easy to imagine that, as a student, Mika was protected not because he was pitied or seen as a victim, but because he was admired. He was reflexively daring. He caught the waves of popular music and fashion, dressed up and sang out, experimenting, inventing, testing, performing himself in the superficially quiescent years between Stonewall and ACT UP, before the Homosexual Law Reform Act and the Hero Parades – before most of us (except for singular boys and girls like Mika), growing up wherever we were in our own small towns and finding the world mostly from a distance via television, radio and magazines, knew what was up. Perhaps it is as simple as this: being twice exposed to social stigmatism, both gay and Māori – two apparent cultural deficits that cancelled each other out – made him appear exotic and charismatic instead of (or possibly as well as) deviant and dangerous. For a very long time, Mika was Neil Gudsell: a boy whose first days were indelibly marked by the twinned experiences of rejection and loving embrace. Not much has changed, really, except that he is now a star for real. Femme and fierce, this is his song, his dance.

Mika’s first overseas trip, to Bendigo, Australia, Christmas 1978. At Christchurch airport: Lindsay, Mika, Auntie Noela and Dawn. This trip took place soon after Mika’s father had died.

I had a mum and dad who loved me, who supported me and who allowed Neil to be special. Somehow if they were alive now I think they’d like Mika as well.

—Mika, from ‘Bunga in a Bucket’

Mika’s first frock, 1969. Posing in front of the house on Tweedy Street, Mika is on the far right.