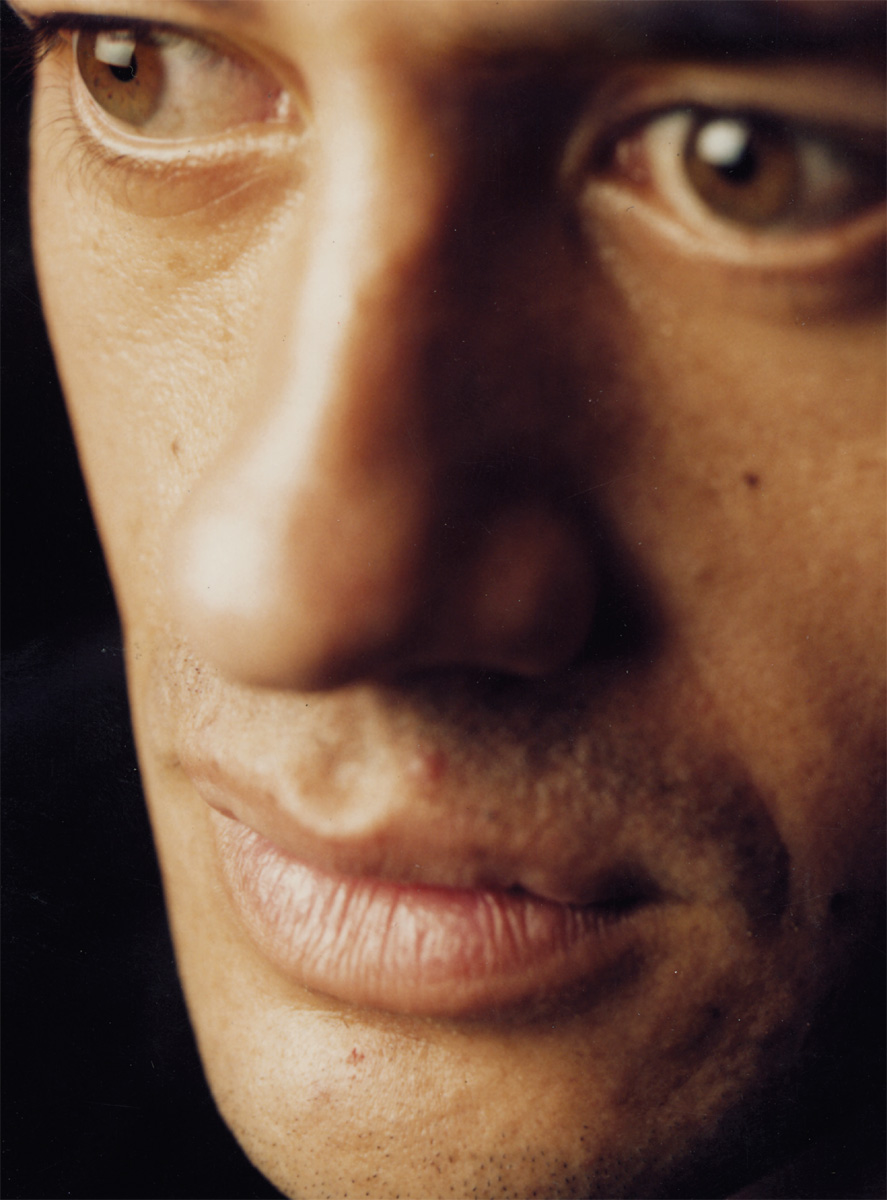

A photo for Mika’s first run at an ‘arthouse’ book, 1988. The pictures (now lost) featured the late Arthur Tauhore and a host of Wellington after-hours legends.

CHAPTER THREE

TĒNEI TŌKU URE | MANHOOD

At first they [the transvestites who were helping me research my role] said I was too macho to be a drag queen . . . which is not something people say too often.

— Mika, quoted in Boniface, ‘Learning a Transvestite Role’

He dances, sings, jokes and acts vaudeville-style, but the portrayed truths are difficult to shrug off as lightweight entertainment.

— Samson Samasoni, ‘Gutsy Cabaret’

ART FOR THE REST OF US

Wellington, 1988. With Jim Moriarty, Mika staged what might be termed a ‘Māori intervention’ into the International Festival of the Arts. Their double-bill of one-man shows was headlined ‘Neil Gudsell and Jim Moriarty Live at the Depot’ and aggressively promoted as a challenge to the otherwise Pākehā-dominated event. Coming second, Moriarty performed an adaptation of Rore Hapipi’s Fragments of a Childhood. First up, though: Mika in Mahi Whakangahau (Entertainment), a loosely autobiographical song and dance about the transvestites and transsexuals on Vivian Street. Mika’s monologues were interwoven with music mixed from the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, as arranged by Aotearoa band member Ngahiwi Apanui, and featuring two ‘Back-up Beauties’, Mere Boynton and Riwia Brown.1 At the heart of Mika’s performance was an homage to New Zealand’s most famous transgender woman, Carmen Rupe, whom he’d met in Sydney two years earlier.

The substantial packet of press clippings, promotional materials, features, commentaries and reviews preserved from this singular event show Moriarty and Mika in the vanguard of a political theatre movement, performing redress against the absence of Māori on New Zealand’s main stages. Nicholas Butler, writing in Victoria University’s Salient, notes its significance:

One of the nice things to come out of this year’s Festival of the Arts, apart from Uncle Rudi the tottering Tartar, is a clear distinction between two diverging approaches to the arts in New Zealand.

On the one hand we have Big Art, Art with a capital A, Name Art, Corporate Art, Money Art, art for, of and by the elite.

Or there’s art for the rest of us, art for, of and by the people.

Take f’rinstance Neil Gudsell and Jim Moriarty live at the Depot, starting this Thursday.

The show came into being, says Gudsell, ‘when the Festival organisers made it completely obvious they weren’t interested in anything significantly Maaori’.2

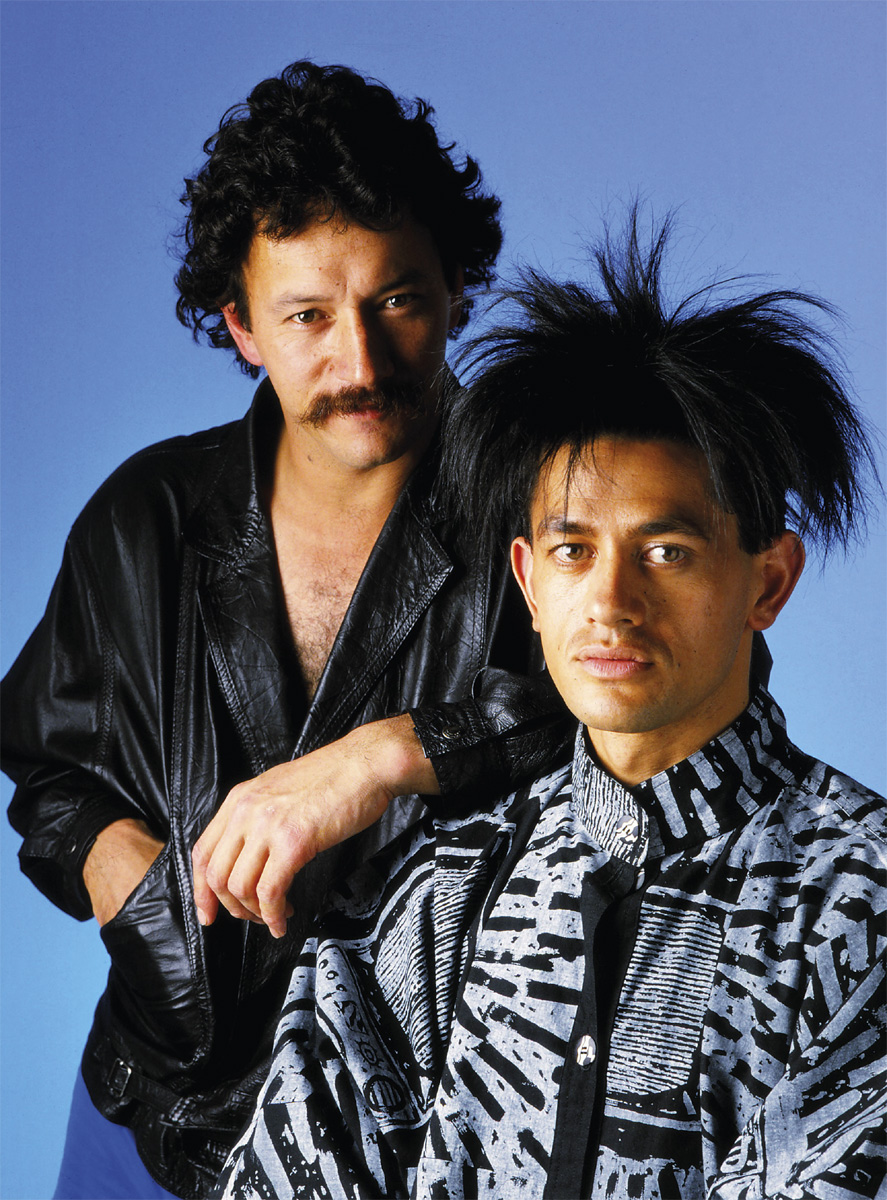

Jim Moriarty and Mika shared the billing in their Live at the Depot show in Wellington, 1988. Photo by Paige MacMillan.

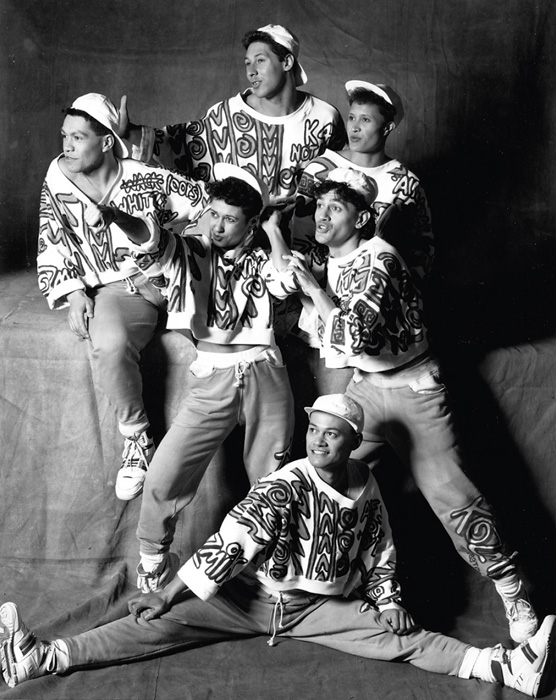

Cast and crew of Mahi Whakangahau, from Live at the Depot, 1988. Back: Mere Boynton. Middle, from left: Riwia Brown, Mika, Ronald Crook. Front, from left: Richard (film-maker), Glen Harrison (costumes), Kneel Halt (DeeZaStar).

Looking back, Mika takes no little credit for his work as producer, raising the funds, promoting the performance, blazing a trail for future festivals in which visible Māori participation is now customary. But there’s a certain déjà-vu, all-over-again feeling to reading about accomplished young Māori performers struggling to break through the glazed surface of the International Arts Festival in Wellington almost thirty years ago. Even now, New Zealand’s performance culture remains predominantly straight, white and rather timid on the surface – although there’s plenty that is not that, both for those who go looking and for those who insist on making us look, as Mika did with Jim Moriarty and company in 1988.

For Mika, his one-man show Mahi Whakangahau represented the culmination of an intense, volatile four years in Wellington. He moved up from Christchurch at the end of 1984 to start at the dance school in January 1985, and then walked away from the school nine months later. The reason? ‘They had a programme called something like “New Zealand dance”, but when I went there was nothing New Zealand about it. When I asked where the Māori stuff was, they essentially said “oops, can’t”’. By then, however, he had wangled another invitation, this time from Te Ohu Whakaari, a Māori theatre company that, while based in Wellington, toured extensively throughout New Zealand and, less extensively, overseas. Mika says that, ‘touring the motu, I learned lots and lots of things about Māori naughtiness – for some reason the old people wanted to tell me all about it’.

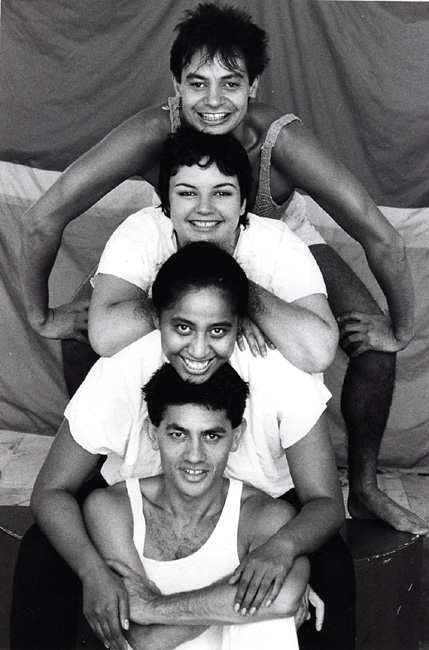

Te Ohu Whakaari, 1986. One of the last NZ Students’ Arts Council tours. From top: Paora Maxwell, Tina Cook, Whetu Fala, Mika. The tour was produced by Briony Ellis.

AND SO I LED THE MARCH

The political movements that stirred first in the 1970s took hold in the 1980s. There had been significant protests in the 1970s: demonstrations on Waitangi Day, the 1975 Land March, the Bastion Point protest that stretched through 1977–78. The rise to consciousness caused by these proto-revolutions seems to have been largely repressed by the dominant culture in a way that became impossible with the advent of the Springbok rugby tour in 1981. The statistics attached to the Springbok protests, as cited by Paul Moon, are impressive: ‘Over almost two months, more than 100,000 people were involved, contributing to 200 demonstrations, with 1,500 individuals charged with offences arising from their protest activities’ (495). He adds:

While this statistical toll gives the basic dimension of the protests, it does not really convey the effects that the tour, and the reactions to it, had on New Zealand society. The most common comment made at the time was that this was the moment when New Zealand ‘lost its innocence’. Although such a view relies on a highly sentimentally charged impression of what the country was like before 1981, undoubtedly the events surrounding the tour serve as a measure of how far the nation had shifted in its values over the previous few decades.

When the Springboks came to New Zealand, Mika was still in Christchurch, about to move onto a more national stage and into the wider world. Being gay didn’t necessarily mean recognising the connection to other struggles for equality. As Mika tells it:

I went on my own to the Springbok Tour protest in Christchurch, wearing my motorcycle helmet – as we all did – to protect my head from the bashing, but more interesting to me, working at a hair salon, was having heated debates with Māori (and non-Māori) who didn’t see the connection between apartheid and Māori, even though at that time, Māori still couldn’t get into some pubs in Christchurch.

Moon, writing from an historian’s vantage point, seems to agree that it takes more than a series of protests, however widespread and vehement, to shake up entrenched attitudes and behaviours:

[T]he entire anti-tour movement was a protest by proxy: New Zealanders fighting for a cause which had almost nothing to do with their daily lives. There was no direct self-interest in the outcome of the protest . . . The irony that there was no similar passion expressed for local race relations was a telling point. (498)

The postcolonial does not, after all, put the past in its place, or plant us firmly into a new period in which we can all be thankful to have moved on. It’s more aspirational than actual, rife with unresolved tensions underlying the progressive narrative.

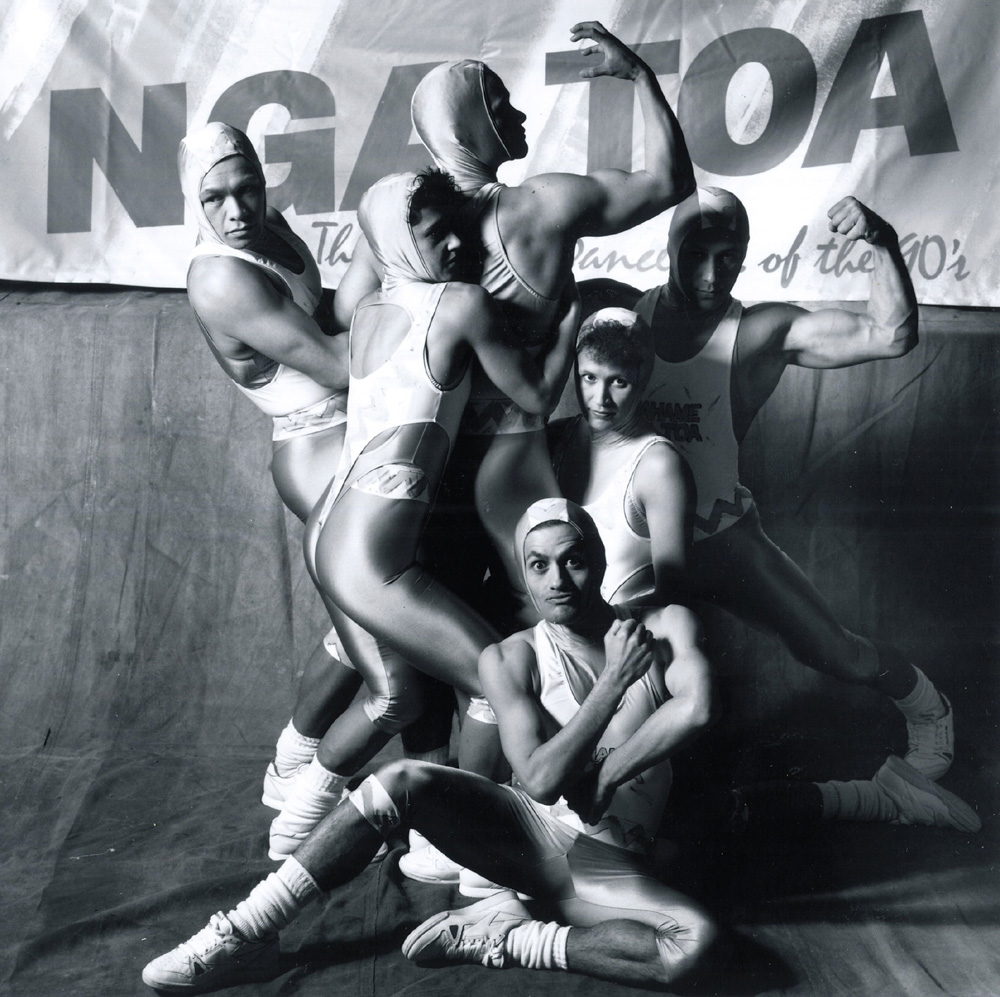

Nga Toa, aerobics champions. Mika (seated front) is framed by, from left, Andrew Tuarae, Ruth Pirihi, David Brown and Michael Molloy. Mika coached the team, who reigned unbeaten for seven years in the NZ Aerobics Teams Championship, 1986–92. Their uniforms were modelled on the US team’s sprinter uniforms in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. The photo was taken by Neil Trubuhovich, who was later lost to AIDS.

Nga Toa, aerobics champions. At back, from left, Andrew, Michael, Kathy. Middle, Ruth and Mika. Seated front, David. Photo by Neil Trubuhovich.

So, too, the campaign for the Homosexual Law Reform Act, which was introduced in Parliament in March 1985 and, after more than a year of turbulent, often reactionary and ugly protest, became law. Of course Mika marched. He remembers: ‘In Wellington, down Lambton Quay, the leader of the gay march couldn’t chant and asked if someone else could. I was with a group from Te Ohu Whakaari; they said “off you go”, and so I led the march.’ For Mika, protests and pride parades were not so different – all opportunities to perform and to see his performances as efficacious. He claims: ‘My chants were evidently so distinctive that I was even mentioned in the papers the next day. The law was changed in 1986.’ And adds: ‘The next big march I remember was in San Francisco with ACT UP in 1992.’ There were other such passionate performers. On one side, Carmen, who is remembered as a tireless, inspirational campaigner for reform. On the other, politicians and preachers, like Norman Jones, who

[s]tanding on podiums in churches and halls around the country . . . preached the same message of intolerance, unleashing tirades against those whom he saw as ‘perverting’ the country. ‘Go back into the sewers where you come from . . . as far as I’m concerned you can stay in the gutter,’ he told a heckler at one of his speeches in 1985. And then addressing his audience, he said: ‘Turn around and look at them . . . gaze upon them . . . you’re looking into Hades . . . don’t look too long – you might catch AIDS.’3

Mika with, from left, Leonie Clark, Michael Molloy and Jackie Mills of Les Mills World of Fitness. Mills is resting on a Suzuki World Aerobic Champs bag. Mika coached and choreographed Jackie for the NZ Aerobics Championships. Photo by Neil Trubuhovich.

The threat of AIDS had become undeniable by this time, but the bill’s supporters argued that legalisation was critically necessary to enable education programmes.4 Opening the closet door, legally, was imperative, the only way to ensure that information about safe sexual practices could be publicly promulgated, that HIV/AIDS cases could be diagnosed early and properly reported, and that the infected, ill and dying could be cared for with dignity and mourned with grace by those who loved them – no small matter, given the scale of the epidemic and the way it amplified the shame surrounding homosexuality at the time.

I WILL SURVIVE

How to describe the fear, horror and grief of that period in New Zealand as elsewhere? Colleagues and collaborators, family members, friends and lovers were stricken and taken from us, as if tapped by an evil spirit – not the angel of death as Norman Jones might have it, sweeping the world of the impure, but nonetheless in a way that, especially in the early days of the plague, seemed unspeakably arbitrary and cruel. A friend would say one day ‘hey, I’m still okay, even though I shouldn’t be given the way I’ve carried on’, and then the next . . .

The ugliness of the illness itself, the way it disfigured so many beautiful and not-so-beautiful men (and women, let’s not forget), especially those in the creative industries, was horrible enough. The callousness of the medical and legal systems, and the indifference of the wider community, compounded the injury, wasted precious time: the time it took to see a doctor, the time it took to recognise how the disease was transmitted, the time it took to begin seeking a cure, the time that might have been spent dancing. It cost innumerable lives and changed everything.

Mika stayed well. So did Carmen. And others. Some were infected and yet live on. The disease remains devastating, and life-threatening, and it is often still a dirty secret. But it is also part of twenty-first century life and art, as one sees in the work of choreographers Douglas Wright and Michael Parmenter, who have incorporated the long-term effects of carrying the disease into the body of their performances. From the start of the crisis, Mika did more than protest. In 1992, for example, he got a scholarship from the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust to study AIDS education in theatre programmes, travelling to San Francisco, New York City, London, Barcelona (for the Olympics), Los Angeles, Sydney and Edinburgh (for his first Fringe festival).5 To educate and advocate in this way can’t change the past, but it makes living in the present meaningful.

TO BE, OR NOT TO BE

No actor’s résumé would be complete without a star turn in Hamlet. So it was for Mika touring with Te Ohu Whakaari to the Sydney Opera House in 1986. This was early in the trend towards Māorifying Shakespeare; he was playing it white, playing it straight. Looking back, he says ‘it was doing what was considered “acting Shakespeare”. More internal racism.’ Not much has changed, he carries on, looking at current productions of Shakespeare by Māori companies, even though the practice is often to dress up the performances as Māori by putting piupiu on the actors and inserting elements of kapa haka. There must be more to it than a not-quite-postcolonial cringe, than whiting up or slapping a bit of brown on the face of colonial high culture:

Yes, Māori should do Shakespeare, ballet, opera. Of course we should. But it’s as if our own Māori whakataukī aren’t enough. I do love Shakespeare, very much, especially Macbeth. I love Mozart, too. But Māori have our own beauty in our words, in our music, and this is what I value.

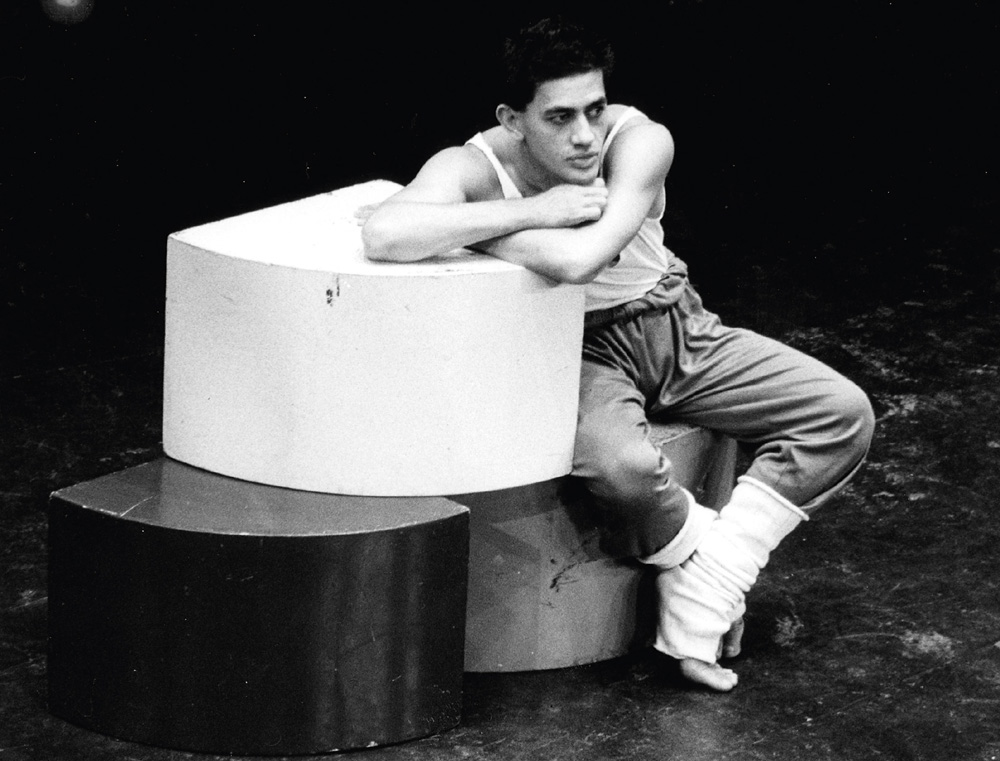

Mika as Hamlet at Sydney Opera House, with Te Ohu Whakaari, 1986.

Productions of the classics can indeed act as a kind of cultural closet, demanding the denial of identity onstage and off, reinforcing ethnic stereotypes and (perhaps worse) reproducing the effects of ‘colonial desire’.6

The Sydney tour was hugely important for Mika, not so much for the opportunity to play Hamlet, although he certainly relished the role. There was a whole world of gayness there, larger and more diverse than any he had experienced before. There was no way he was going to miss out, as he recalls:

Rangimoana Taylor, our (gay) director, came into the room I shared with Paora Maxwell,7 my co-actor, who was also gay, and said ‘you are to have no involvement with the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras whatsoever’. Paora and I looked at each other. I don’t remember what we said, but the look was enough. Later that night, two Māori boys wearing nothing but g-strings and sneakers were dancing like nothing you’d ever seen on Oxford Street.

The decision to join the parade was fateful in more ways than one, he says: ‘That night, on the way up, a voice called to me – “Kia ora, you from New Zealand?” It was Carmen. That is how we met.’ He says now that ‘Carmen was one of the most authentic Māori I’ve ever known’. She was an avatar of self-determination and queer liberation for Mika, as for so many others.

Carmen. So much more than calling her a transgender icon would indicate. Born Trevor Rupe in Taumarunui in 1936, she was out almost from the start, making the shift from performing drag to living female in the repressive 1950s and 1960s. In doing this so publicly, she tossed open the closet doors for many, many others. She was infamous as the proprietor of Carmen’s International Coffee Lounge and The Balcony strip club in Wellington. She was above all a passionate political campaigner, sexual liberationist and social activist. And she just happened to be cruising the parade as Mika danced by. What were the chances that these two virtuosic self-fashioners – the former Trevor Rupe and the soon-to-be-former Neil Gudsell – would cross paths in this way?

TO BE REAL, OR NOT TO BE

Drag performance is not as simple as it looks. Nor is it so singular. While the high visibility of drag queens makes them emblematic of queerness, cross-dressing as such is also a pastime for straight men at parties, in pantomimes and revues, and for more private pleasures. They flirt with the queer in the same way that many of them dabble in the theatre. Seen from a distance, many such straight drag acts are homely reflections of what can be seen on television, in films and popular musicals (think of Dame Edna, Some Like It Hot, Tootsie, Mrs Doubtfire, Victor/Victoria and Mrs Brown’s Boys), and they seem ultimately to reify gender norms. In crossing into performative codes that are socially marked as female or feminine – wearing lingerie and/or dresses, putting on make-up, falsettoing and simpering, etc. – they highlight the codes per se, and re-mark themselves as men. That is, underscoring their acts of acting as women, they remind us that they are, after all, really men, and real men don’t do such things.

In queer terms, however, drag performance can be seen as a form of serious play, in which the pleasures of performing as an ‘other’ can be seen to carry (consciously or not) critiques of gender normativity and the social order it represents. In her groundbreaking book Vested Interests: Cross-dressing and Cultural Anxiety (1992), Marjorie Garber says that ‘transvestism is a space of possibility structuring and confounding culture: the disruptive element that intervenes, not just a category crisis of male and female, but the crisis of category itself’ (17, italics in original). For Garber, ‘The cultural effect of transvestism is to destabilize all such binaries: not only “male” and “female,” but also “gay” and “straight,” and “sex” and “gender.” This is the sense – the radical sense – in which transvestism is a “third”’ (133). In Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest, Anne McClintock follows Garber in noting that cross-dressing can be seen as a ‘transgressive embodiment of ambiguity’ and observes:

Cross-dressing, as a culturally variant example of mimicry, is a case in point. Clothes are the visible signs of social identity but are also permanently subject to disarrangement and symbolic theft. For this reason the cross-dresser can be invested with potent and subversive powers. (67)

Writing around the same time that Mika was consolidating his performance persona, in the early 1990s, Garber defined drag as ‘the theoretical and deconstructive social practice that analyzes these structures from within, by putting in question the “naturalness” of gender roles through the discourse of clothing and body parts’ (151). Drag performance, especially in the queer context, can be seen as intrinsically political, Garber insists, and ‘transvestism has been the site of activism in part because it is activism in sight’ (159).

Pierre et Gilles-inspired Photoshop image by Arjan Hoeflak, with whom Mika worked from the early to mid-1990s.

Mika’s performances seem more celebratory than critical, but they are no less political for being such fun. His performative experimentation was surfacing at the same time that Judith Butler so controversially asked, ‘In what senses, then, is gender an act?’8 Some twenty-five years on, Mika’s performances may seem to be more pastiche than parody, but they still trouble gender in performance, playing with its conventions in order to expose and challenge the dominant culture. That said, he doesn’t seem to be trying to ‘undo gender’ as Butler later proposed; he has no such problem with the idea of ‘bodily autonomy’, any more than he seems to be troubled by the question of ‘realness’.9 Rather, he models the sartorial conventions of gender and sexuality, and of race and culture, in extremity, as costumes from which to fashion himself, freely, onstage and off. If the status quo is upended as a result, so much the better.

In any case, Mika’s drag is not quite the same as Carmen’s. He credits his ‘close queer friend’ DeeZaStar, who, during the 1991 tour of Totally Uncut, suggested that he ‘remove the tits’, pointing him towards the creation of a gender-fluid queer identity that owes more to Grace Jones and David Bowie than to Divine. He’s not identifying as a woman, even when he’s dressing up as one. Nor would he necessarily identify himself as a transvestite-esque ‘third’ per se. He’s playing himself, deliberately dancing with the demarcations of gender, resisting categorical imperatives, provocatively deconstructing the masculine and remaking it as a creation of his own imaginary, from the threads (pun intended) of the performances he sees everywhere around him.

ONE MAN SHOW

Soon after the Sydney tour, Mika left Te Ohu Whakaari and went to Dunedin to work on the ‘Te Māori’ exhibition. It was during his time in the South Island that he was inspired to write his first one-man show: ‘My research, up till then, had always been Liza Minnelli and Barbra Streisand. At a record store, I found a cassette with a dread-locked black woman called Whoopi Goldberg: her one-woman show. Overnight, I began my script, which became Mahi Whakangahau.’10 Like Mika, oddly enough, Whoopi Goldberg started her career as a straight actor. She was trained in the tenets of Stanislavskian psychological realism at HB Studio in New York City, and traversed the axis between the conventional and the avant-garde in New York and Europe starting in the late 1970s. She’s carried on with theatre and film in the years since, famously. But it was her channelling of multiple voices through her own, weaving social commentary with comic irony, first in The Spook Show (1983) and then in Whoopi Goldberg on Broadway (directed by Mike Nichols, 1984), that gave Mika a way of imagining himself in much the same light.

What’s more, it was around this time he also discovered Grace Jones, whose One Man Show (1982) shook the whiteness out of the queer.11 Such breakout performances – bending gender and race into something critically beyond camp – inspired his own, first in Mahi Whakangahau, and then in everything that followed. Looking now at the video of A One Man Show, as Jones swirls in an enormous, ladybird-dotted hoop skirt, we see intimations of Mika’s native drag, his Plastic Māori and Black Carnival-esque promenades on stage, in films and videos, and in the streets.

The 1988 show at the Depot was in many ways the culmination of Mika’s foray into what we in the theatre called at the time ‘straight acting’ on stage – which was what one did in plays that, like Mahi Whakangahau, even if they had musical elements, were not musicals per se. In Mahi Whakangahau he showcased himself as a versatile, charismatic performer, someone who could successfully put the seemingly contradictory pieces of his personae – gay and Māori, private man and public figure, authentic and pastiche, sincere and ironic, rampant soloist and celebratory collectivist, small-town aspirant and cosmopolitan star – into play. Then, as now, he could attract fiercely loyal audiences, collaborators and supporters as well as controversy. Perpetually in motion, he seems always to be leaping to the crest of the next political and performative wave, channelling the currents of popular culture into staged events as a kind of instant playback for everyone around him.

PLAYING IT STRAIGHT ONCE MORE

After starring more or less as himself in Mahi Whakangahau, Mika took on a featured supporting role in the first season of Shark in the Park, Television New Zealand’s own cop show – a series modelled on the groundbreaking, long-running American programme Hill Street Blues.12 Mika recalls that he was cast as (heterosexual) Constable Ra, ‘the most boring Māori character you can imagine, of course, as written by a white person’. From the vantage point of the media-saturated twenty-first century, Shark in the Park offers an entertaining and distinctive, if somewhat skewed, window on late-1980s New Zealand. We don’t just see life on the streets as processed through the twin lenses of cultural conformities and imitative imaginaries: gritty as a kind of style choice, always a bit sheepish, as if just kidding. We also catch glimpses of a remarkable cohort of New Zealand actors and directors, many in the first flush of their careers, among them (stop me if I leave anyone out) Rima Te Wiata, Roy Ward, Colin McColl, Robyn Malcolm, Annie Ruth, Geoffrey Heath, Jennifer Ludlam, David Geary, Ginette McDonald . . . so many familiar faces, acting much as we’ve seen them do in the years since.

Mika as Constable Ra in Shark in the Park.

Mika as Constable Ra looks to be at the edges of the action, pri mar ily, but he makes the most of it. He’s spunky, charming, quick to smile at his co-stars and at the camera, ready with a cheeky quip and happily in the thick of it – a classic Kiwi character. He may have been playing it straight, flirting with the chicks, and talking chicks with the lads. Those are the lines, the situations. But in hindsight it seems he also finds the occasional opportunity to eye up his male co-stars, and to wink, just a bit, at the camera. Then, too, there’s a real social conscience underlying the scenarios and exchanges. The female characters bond with each other, fend off passes, debate their role, and recognise their own precarious status in the fallen women they meet on the beat. The male characters negotiate degrees of mateship, manage messy marriages and reckon with the changing times.

From left: Mika, Ned Ngatai and Carmen in the Carmen documentary, directed by Geoff Steven, 1989.

But it’s still the late 1980s. Everything’s casual on the show: casual sexism, casual homophobia, casual racism. Looking at it now, it also seems more than a little camp, or certainly not quite in earnest. The idea of realism is there, but the scale is a tiny bit off. With its detailed evocation of period Wellington – hair and clothes, cafés, cars and streets, first-wave computers alongside other soon-to-be-outdated technological objects (typewriters, telephones) – it looks self-consciously just on the wrong side of hip and, somehow, prematurely nostalgic for a New Zealand already rapidly being left behind. Certainly that’s what Mika did: ‘Needless to say, I only lasted one season. The day it finished, I moved to Auckland, where I was cast to play a young Carmen Rupe in the biodoc Carmen.’

WHAT HAVE YOU GOT FOR ME NOW?

Carmen, directed by Geoff Steven (and available for viewing on the NZ On Screen website), is a wonderful mixture of reality and fantasy. Carmen narrates her life story, inviting the cameras to join her in her current and past homes, meet family and friends, see the places of her childhood, walk the Wellington streets, sit with her in cafés, and watch her perform the hula and an odd version of ‘Hava Nagila’ in a theatre. We see her huge cache of photos: Trevor Rupe in the early days, as a child at school, in the army, and Carmen Rupe coming out in glamorous drag. Interspersed are sometimes fantastical reconstructions of Carmen’s memories. Adult Carmen stands by the river near her childhood home, talking about the pleasures of playing in the imaginary wild as a young boy takes over and the film transitions from the reality of the natural environment to a flight of fancy. The boy enacts dressing up ‘not as Tarzan, but as Jane’ and (as the image magically morphs) playing with gorgeous drag queen fairies in the heightened lushness of a Hollywood-esque soundstage.

We catch a glimpse of Mika, playing Carmen’s memory of a concert party while she was still Trevor and in the service. And we take a longer look as Mika again shows us Trevor, this time dressed in a black suit, looking impossibly fresh and naïve, entranced by two glorious queens in the Auckland Domain toilets. Later in the film, following Carmen’s recollection of her decision to wear only women’s clothes, we see Mika on a little stage with projections of South Seas vistas – postcard clichés – behind him. Carmen says ‘I’m a try-sexual. I like to try anything’ in voiceover as Mika performs the hula in a sequence of costumes that takes him from his black suit into various versions of flowery dress and grass skirt, with wigs and bling to match. As the film draws to a close, Carmen, in close-up, says:

In the end, you’ve lived this kind of sordid, seedy life. I’ve never been ashamed of it. I’ve always been honest and I’ve always looked at it as a ‘been there, done that’. I usually say, ‘I enjoyed it. I loved it.’ I’m not a hypocrite, and I just say ‘put it aside . . . what next have you got for me now? I’ll try anything else.’

The camera shifts to a shot of her by the road in Kings Cross, Sydney. It’s dark, raining; the cars are passing her by; the lights glisten, casting her in silhouette so that she is simultaneously herself in the present and young again.

The sense of transference between Carmen and Mika is carried into the credits. She’s in a trenchcoat, wearing dark sunnies, pulling back layers of crumpled muslin and lace curtains to reveal a kind of ad hoc curtained stage – like a porn set-up – with Mika on a bed in full drag, hot pink dress, big wig, seducing a half-dressed hunk of a man. Carmen pulls another curtain. We see Mika again as Carmen in her Lounge serving a suited man who positions the teacup to indicate the type of sex he is after. Another curtain, another image of Carmen’s past, performed by Mika, this time in gold lamé, twirling a parasol and posing for a man holding a camera. Another curtain: Mika in a tight, shiny green miniskirt, under a lamp post, beckoning to an unseen john (the audience?), and then turning away towards car lights that pull up and shine through just beyond the backdrop. It really does seem that Mika is the young Trevor, the young Carmen. He’s loving the performing, loving her; he finds her in himself, and himself in her – as actor and as being. Mika is still Neil, but not for much longer.

Mika with Carmen, c. 1980s.

When I look back at it now, I didn’t realise how lucky I was.

— Mika