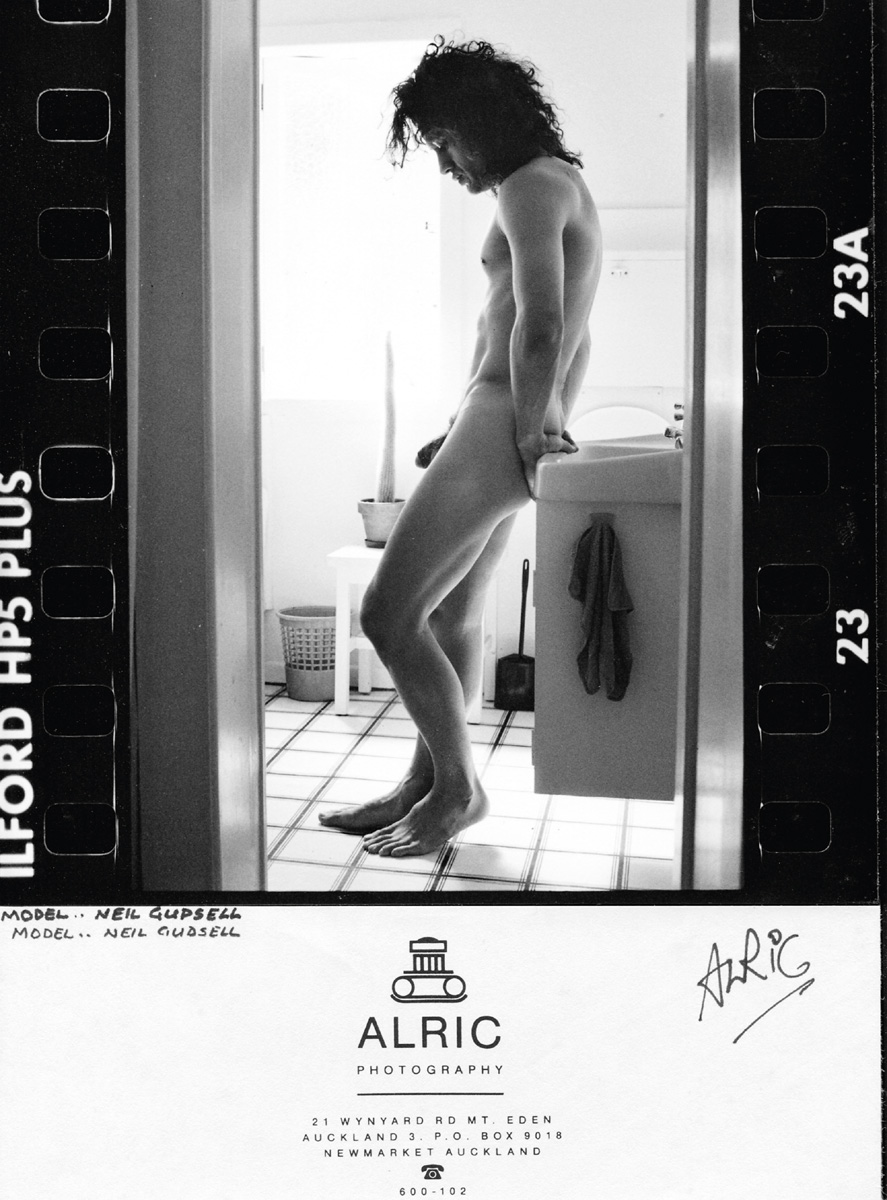

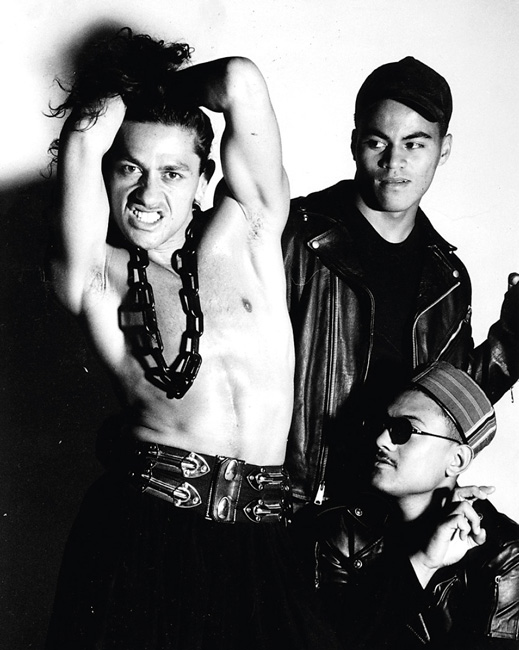

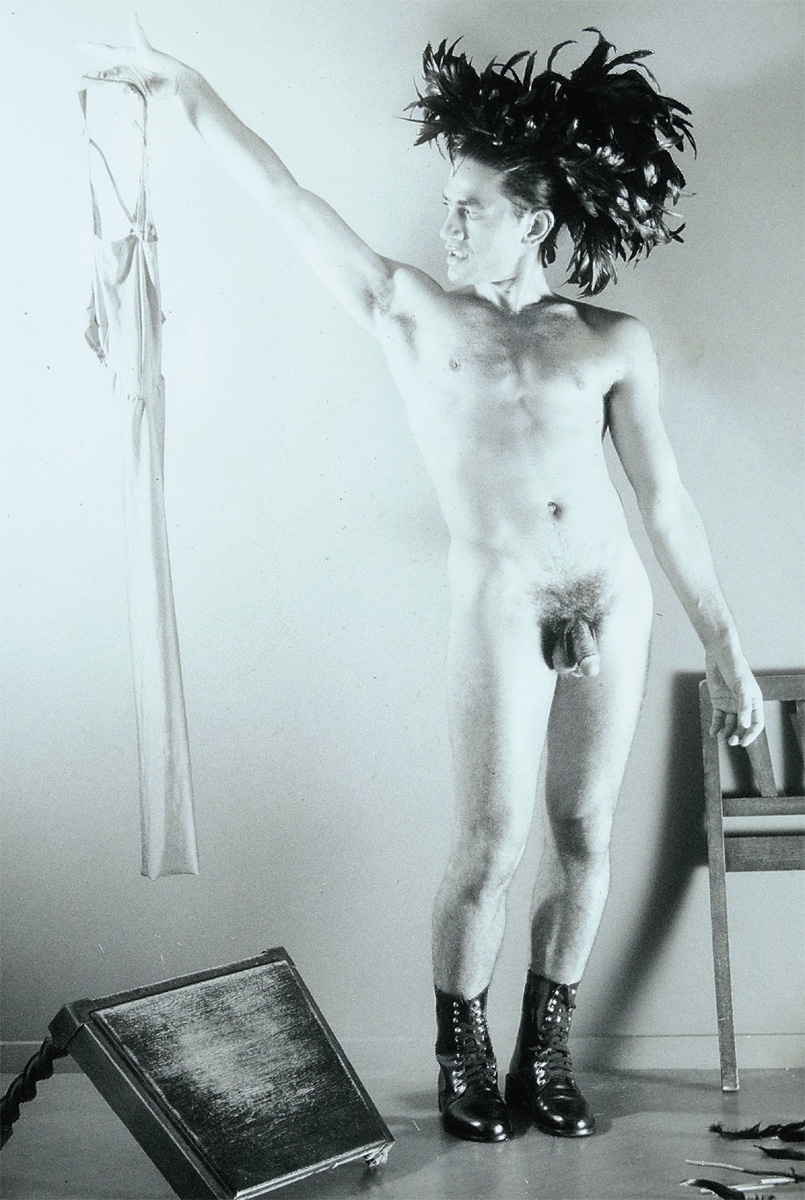

Photo by Albert Sword. Shot in Mika’s apartment in St Marys Bay, Auckland, late 1980s.

CHAPTER FOUR

I HAVE LOVED ME A MAN

I was at Warner Music HQ about to release ‘I Have Loved Me a Man’. Dalvanius and I were sitting in a car outside the studio. He said, ‘Neil Gudsell is not a name for New Zealand’s Sylvester’ (number one worldwide disco hits, big black queen, etc.). ‘It should be something like . . . Paulie or Riki . . . something that’s not male or female.’ Then he said, ‘Mika.’ So in the back of a Toyota Station Wagon, Dalvanius gave birth to Mika.

— Mika

SAFE / LOVE / = / LIFE

— Mika

YOU HAVE TO RECORD THAT

And so somewhere along the way – in stages, really, rather than all at once – Neil Gudsell became Mika. It seems fitting that Dalvanius Prime was midwife both to the record and to the man. Prime was the creator of ‘Poi E’, with the Pātea Māori Club,1 a hugely popular song that went platinum as it crossed the lines between traditional and contemporary, and between the then still largely segregated Māori and Pākehā worlds, playing on the radio and on the kapa haka stage.2 Prime was also an ardent community activist, a mentor and advocate for youth, and a leader in the campaign for the return of mokomokai (the preserved heads of Māori ancestors) from overseas museums.3 As with Carmen, with Dalvanius Prime, Mika could see ways of reconciling his desire for stardom with his activist impulses. Both helped Mika create a character for himself beyond what was offered to him on the conventional stage.

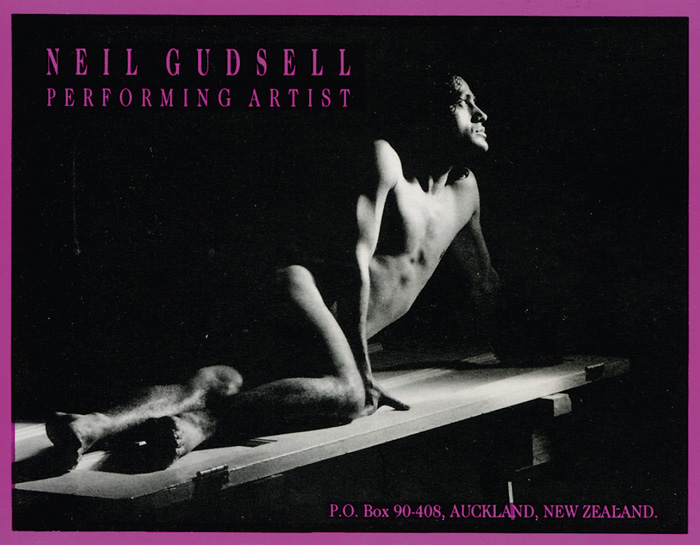

‘Neil Gudsell, Performing Artist’, postcard, c. 1989.

At heart, Mika’s show at the Depot, Mahi Whakangahau, had been about his life, and the show changed his life. He’d spent the years leading up to 1988 exploring relatively traditional training and career paths: dance and theatre, narrative television and documentary film. But by the time the 1980s were coming to an end, he was ready to launch himself as an artistic entrepreneur. He didn’t so much reject the training he’d received along the way as put it in service of his creative impulses, which in turn were fuelled by his social imperatives. Centre stage was Carmen as both role model and chief cheerleader. There were others as well, as Mika recalls:

Maui Records founder and producer Dalvanius Prime came to my show. During the show I remember I did a medley of NZ songs. One of them was Allison Durbin’s ‘I Have Loved Me a Man’. Dalvanius came backstage and said ‘you have to record that’. This was Dalvanius – producer of Prince Tui Teka’s number one hit, ‘E Ipo’, and of Hinewehi Mohi’s hits, of Māori Motown and the Fascinations fame – so of course I said yes.

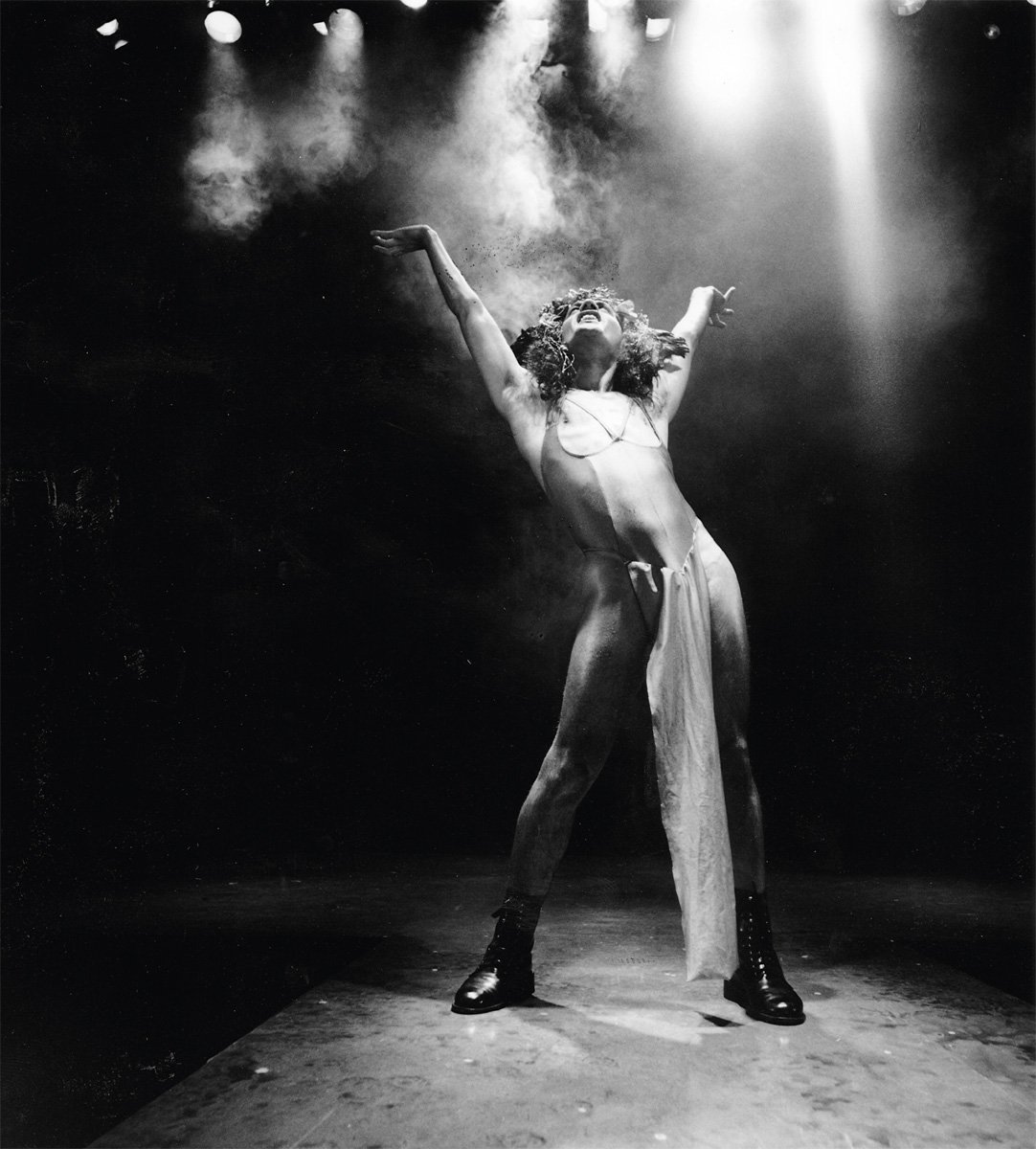

Still from the ‘I Have Loved Me a Man’ music video, directed by Luke Parata, 1990. Mika’s recording of the song was banned from the radio.

Seen side by side, the two performances of ‘I Have Loved Me a Man’ – recorded by Allison Durbin in 1968 and by Mika in 1990 – could not be more different.4 The first begins in a psychedelic haze and what might be paisley cut-outs, rendered in fuzzy black and white. Durbin emerges as a silhouette from the shadows in a miniskirt, long dark glossy hair parted in the middle, fake eyelashes against porcelain skin. She stands, rooted in place, her legs made invisible by the fog from the knees down, arms almost rigidly arched at her side, hands semi-fisted, and sways almost wildly. In close-ups we see her head tossed back, eyelashes fluttering as if she’s half-stoned or, as the song implies, in the throes of ecstatic remembrance: ‘I have loved me a man / like my mama did,’ ‘his hands like my daddy had’ and ‘lips that kissed away the tears’. From my perch in the twenty-first century, her performance of the song seems unwittingly perverse, a blithe call-out to the dubious pleasures of incest.

Mika’s video begins with a blue screen and a synthetic beat that starts by sounding like a typewriter, then morphs into a dance track. Text appears: AIDS is a four letter word / so is / LIFE / LOVE SAFE. As the LOVE SAFE title fades, we see a man in what look to be boxer shorts, back glistening, walking towards another man, who is also topless, wearing a long draped skirt and standing by a large concrete-looking mill-wheel complete with push-pole. A demure girl, with long wavy black hair covering half her face, wearing a flowered dress, stands off to the side. As the first man begins to push the wheel, the camera pulls back. We glimpse another draped man, but cut almost immediately to a close-up of Mika, tousled shoulder-length hair, dressed in a loose leather-ish jacket open enough to glimpse his chest, his back against the wheel, arms outstretched. He begins to sing: ‘I have loved me a man, yeah baby . . .’ The video proceeds via quick cuts: close-ups of Mika; of the shiny bare chests (except for bling) of the male dancers; of three women – no wait, the middle one is Mika . . . no wait, are they all Mika? – in gold lamé strapless party dresses;5 of Mika face to face with another beautiful man stroking his cheek against the background of a series of shiny-chested men, some wearing ornate crosses; and so on. As he sings ‘I have wed me a man’ the words SAFE / LOVE / = / LIFE in sequence take up the screen. When he gets to the bit about ‘I will raise him a child / like my mother did’ we see Mika and the girl in profile, so that he sings to her almost tenderly. After multiple changes of hair and costume, he crosses to a set of blue-painted steps, and steps up. As the ensemble turns to face him, he faces us and dances freely. The final shot is of him back in gold lamé with the ‘girls’, for one final ‘and I have loved me a man’.

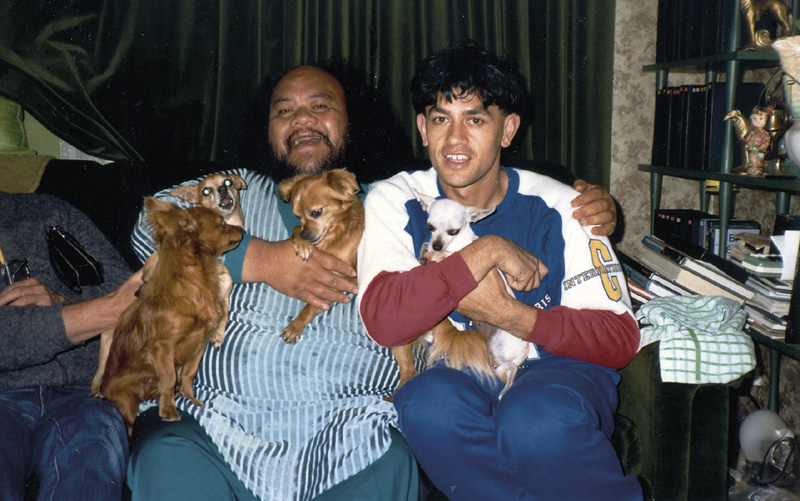

Dalvanius Prime with Mika, Anzac Day, 1987, just before Mika received the call telling him his mother had died.

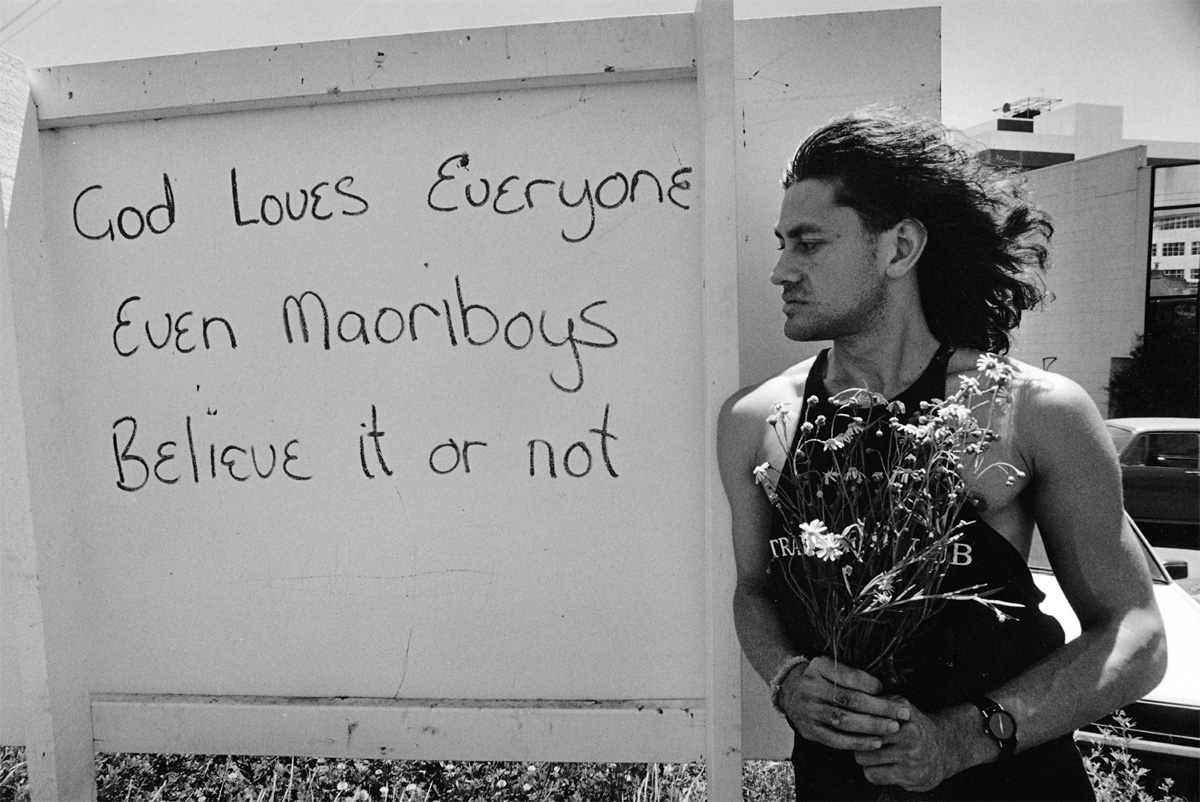

Innocuous as it might seem now – he says he wasn’t seeking to stir – Mika’s recording of ‘I Have Loved Me a Man’ took a poke at New Zealand’s otherwise complacent, heterosexual-by-default surface. He says his record did well enough as pop music, that it ‘bubbled under’ in the charts. But as a social provocation, the song and the video made the headlines. Mika’s video is of its time, just as Durbin’s was. Oddly, though, Mika’s performance seems the more innocent, its cheerful sensuality about the joys of love no matter whom he’s facing, as much for the girl – nothing paternal in it – as for the men in various stages of undress, and for the pleasure of the dance no matter what he’s wearing.

IMAGINE FOR A MOMENT . . .

The end of the 1980s also saw Mika begin collaborating with the pioneering film-maker Merata Mita. He remembers being instantly drawn to her work:

Around 1988–89, in Auckland, I had a Mongrel Mob lover. We saw the film Mauri. Leaving the theatre we had a heated argument about the meaning of the film. Imagine for a moment: me, the NZ gay icon, and my lover, the ex-gang member, having it out in the street.

Mauri (1987) was a landmark in New Zealand film-making, not only in its subject matter – the effects of pervasive racism on an isolated Māori community – and its politics – an argument for land rights, featuring Eva Rickard – but also because its director was only the second Māori woman to direct a feature film. As a film-maker, and as an activist, Mita set out to create a distinctive, culturally informed aesthetic approach. For Māori film scholar Ella Henry, Mita’s work represents ‘the embodiment of Kaupapa Māori principles, peeling back the layers of New Zealand society, to explore the ways that Māori language, society and culture have been systematically undermined by the pervasive dominant culture’.6 Merata Mita, Henry says,

stormed the indigenous world with feature documentaries that exposed the underlying and institutional racism permeating New Zealand society, with Bastion Point: Day 507 (1980) about the occupation and eviction of Ngāti Whātua from their tribal homelands; and Patu (1983), an exposé of the deeply divisive tour of New Zealand by the Springbok rugby team in 1981.7

Henry’s account is as personal as it is academic. For her, as for Mika and many others, Mita broke open the colonial mould that had constrained Māori artists, especially those who saw themselves also as activists.

Mika with Merata Mita at the inaugural Wairoa Māori Film Festival, 2005.

Mika closed the argument with his Mongrel Mob lover by announcing: ‘I’m going to find Merata Mita’s number and get her to direct my next show.’ She invited him to meet. He gave her his script for Uncooked, and: ‘Within a few hours she rang me back and asked “are you gay?” I said “yes”. She said “and you don’t mind?” And I went “no”. She said, “come round immediately, I’ll direct your show”. That was the beginning of our long friendship.’ Such encounters – as much chance as intentional – with the famous and the not-so have continually shaped Mika’s career. It looks as though he planned it, but just as often he was simply keeping his eyes open, as alert to the gifts of others as he was eager to make something new of and for himself.

OSH BAA DOOSH!

As directed by Mita, Mika’s first international solo show was Neil’s last: Neil Gudsell Uncooked, at the Adelaide Fringe Festival in 1990. On stage, he role-played his way through a range of characters, crossing every which way, including from the almost straight to the definitely fruity, and from old (an elderly man in a rest home) to the very young, as this excerpt from his monologue as Riki the skateboarder demonstrates:

Osh baa doosh!

Hi, my name’s Riki and I’m a skateboarder . . . What are you? I used to be a rapper, but my mum reckons I couldn’t rap up fish ’n’ chips in a newspaper. But rapping ain’t really my scene anyway. I’m really into skateboarding, Frisbee throwing and the ‘Cosby Show’. See, I’m drinking Pepsi, the choice of a new generation. I’m wearing Vision and my Avia laces hang loose. A real American . . . almost? (looks at skin) Guess what’s really big in the USA right now? . . . drinking fish oil!8

The text is a masterpiece of American brand name-dropping (McDonald’s and 7-Eleven) and contemporary cultural referencing (Michael Jackson, homeless men, cops). It’s also eccentrically autobiographical:

Real American hot dogs and a lino floor with a huge pinball machine. Yes, punk it up. I bought this piece of lino and every morning I’d get up and drink some fish oil and do a backspin.

Mum would say, ‘Stand on your feet, ’cos that’s what God gave them to you for.’

I said, ‘Who?’ I think mums are so uncool. She was even more uncool when I called her Dawn. Well, American kids are all rich, have swimming pools and call their mums by their first names all the time.9

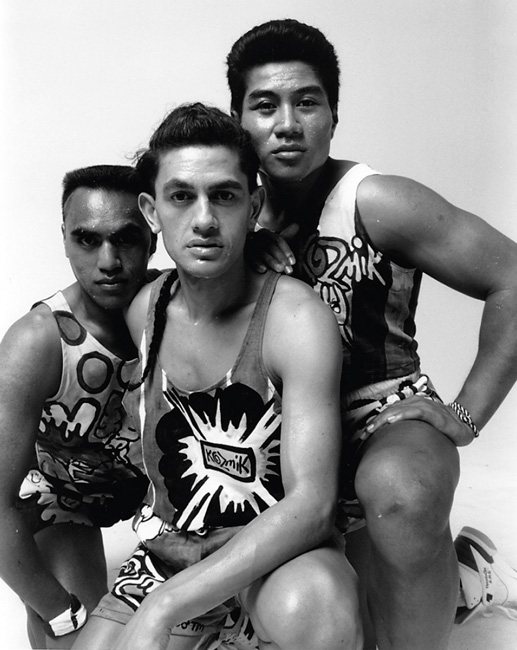

Mika as Riki, one of his many characters in Neil Gudsell Uncooked, directed by Merata Mita, Adelaide Fringe Festival, 1990.

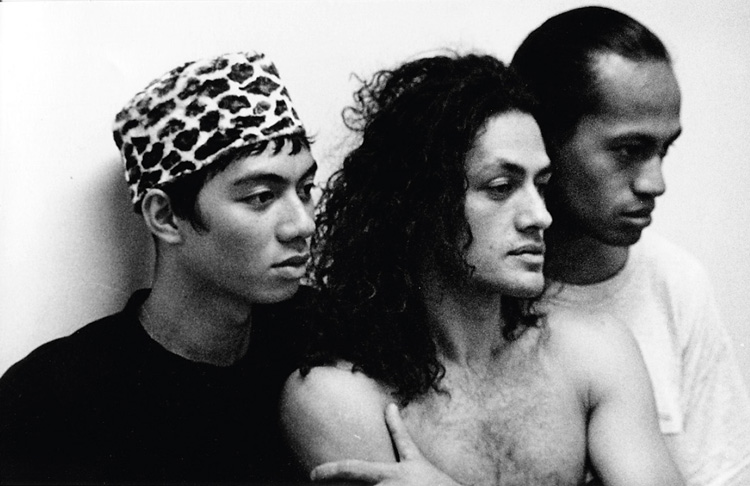

Thomas Tai, Mika and August Lam in Uncooked. Mika’s character was called Sam Steroid; Thomas and August played gym instructors. August went on to be David Tua’s personal coach.

Poster shot for Neil Gudsell Uncooked. Photo by Neil Trubuhovich.

The hallmarks of fully grown-up Mika in performance are present in Neil Gudsell Uncooked. He plays variations of himself: from cute and keen to sharp and savvy, alone and with others on the stage, through direct address, song and dance, dressing up and stripping down, almost straight and gleefully fruity. For Mika, it was the culmination of the decade of performative experimentation: from working with his dance crew in Christchurch to his Māori theatre and cabaret collaborations and the nightclub shows that allowed him the greatest degree of sexual freedom, and from Springbok and gay rights protests to AIDS activism. As the 1980s turned into the 1990s, he made up his mind:

The day the Adelaide Fringe Festival finished I flew to Tokyo for the World Aerobic Championships. I came in eighth male and retired. I wanted to be an artist.

YOU WILL ANSWER TO GOD FOR WHAT YOU DO!

In 1991, Neil Gudsell became (almost) totally Mika in Totally Uncut. Merata Mita saw Mika as courageous as well as talented. She told him he was the first out gay Māori man she had met in the industry, which to her was sad, because there were so many gay Māori and so few role models, even in the creative industries. In Mika’s words:

She said to me, as Dalvanius did, ‘once you take this step – coming out – you can’t ever go back’. To be honest, I probably did hesitate. But I knew from a very, very young age that my calling was not to be Dr Ropata on Shortland Street – nothing wrong about that but . . . I think sometimes we imagine careers that we think we should want, but then we get to a point where we realise that we have the career we really want. I’m one of the lucky ones.

Mika Totally Uncut tour, 1991: Mika with hip hop dancers Roy and Fred. The tour was created to promote ‘I Have Loved Me a Man’. Mika gave away free condoms in specially designed packs.

As explicit about gay desire and AIDS as it was, Mika’s performance of ‘I Have Loved Me a Man’ was radical for the time, and it might be so even now. On stage, Mika tossed condoms at the audience – causing a Christian furore at least once, in Nelson, when the parents of a thirteen-year-old girl complained that their daughter had picked one up; they said, as one newspaper reported: ‘You will answer to God for what you do!’10

Mika’s performances were becoming more extreme, often in direct response to attempts to force him back – if not into the closet, then certainly into line. The push came from the left as well as the right, from those who believed that mainstream cultural acceptance of homosexuality could be gained only by denial of differences that were complicated by the intertwining of sexuality and ethnicity. Mika remembers being told by Merata Mita that some of the AIDS Foundation’s members were so actively antagonistic to the ‘I Have Loved Me a Man’ project that they attempted to block its funding. Dalvanius Prime, as the recording’s producer, also was confronted with homophobia in the studio by other Māori, who attempted to stall the project. Ironic, then, that Mika was able to turn instead to a right-wing anti-gay church for completion funding, and that Warner Brothers picked the single up for wide distribution.

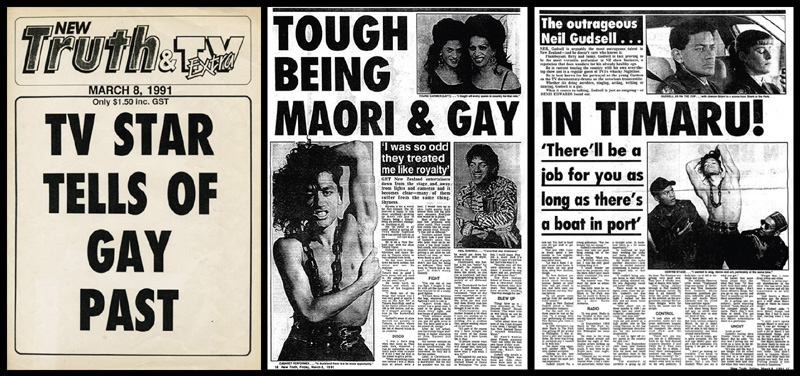

Mika makes the headlines in the New Truth & TV Extra, 1991. Looking at the headline, Mika recalls the early 1990s: ‘It wasn’t really that tough. In some ways it’s harder for kids now. At least back then we had ghettos to hide in. Those communities are long gone.’

‘I Have Loved Me a Man’ went global with Mika on his Juiced tour. It was still a DIY enterprise. His costume fit into a backpack. The tiny, skintight red leotard (shades of his aerobics champion days), six-inch heels and Doc Martens marked him as more gender-contradictory than gender-fluid, perhaps. Closer to home, his coming out made headlines, as he recalls:

The banner in Truth screamed: ‘TV star comes out gay’. The only TV programme brave enough to show the video was the last ever Radio with Pictures, still NZ’s iconic music video programme, and TV3’s Nightline, where I performed the song cavorting half-naked with Joanna Paul and Belinda Todd. Belinda became a big supporter of mine; she kept putting me in things because I rattled the cages.

Juiced poster shot by Alistair Guthrie, 1991. Mika recalls: ‘This was my first world tour show. Me with a backpack, high heels, backing CD and an Afro feathered wig. San Francisco, New York City, Barcelona, Edinburgh . . .’

He sounds improvisatory, cavalier even, as though he simply leapt onto the stage and in front of the camera to do what came naturally. To some degree this is true. But what collaborators experienced and audiences saw was a disciplined convergence of craft with spontaneity, of desire for celebrity with refusal to kowtow to the dominant culture.

From the Juiced Smokefree schools tour, 1991. From left: Filemoni Filemoni, Mika, Philip Leotalu.

From a performance of Juiced in one of the NZ international festivals of the arts, Wellington, early 1990s. Filemoni Filemoni, Duane Evans, Tutevera Wichman, Wairua Sadler, Mika and an unknown man.

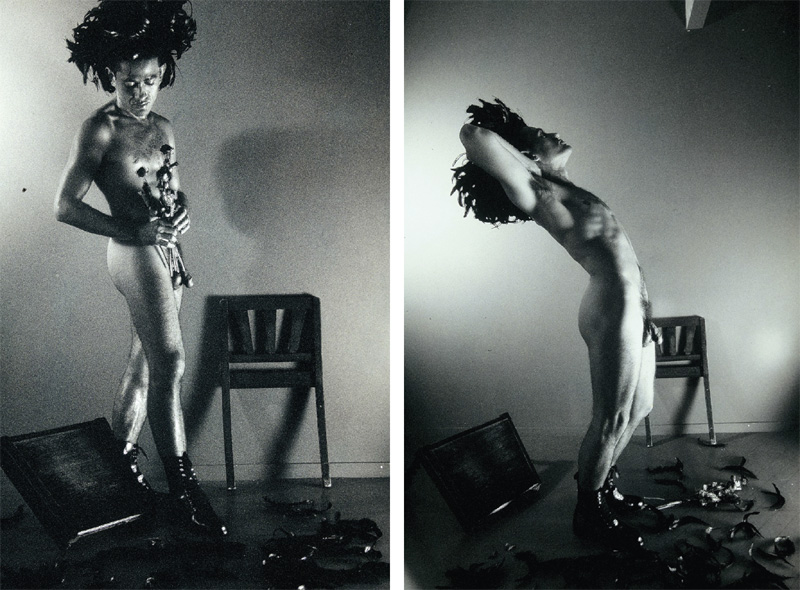

Photos by Albert Sword. Mika says: ‘Albert and I met at one of those 1980s gay events. He invited me to pose. I loved it. I loved Josephine Baker, Eartha Kitt, Grace Jones, and those women who would bare all. Why men don’t do it more, even now, is beyond me.’

If this book were a film, we’d see Mika’s travels, shows and encounters during the early 1990s as one of those maps on which the lines keep being drawn and redrawn: Adelaide to Tokyo to Barcelona to San Francisco to London to New York. In 1992, for example, while travelling the world on a Winston Churchill Scholarship ‘to study AIDS in education using theatre methodologies’,11 he performed at the Barcelona Olympic Games Festival in front of 5000 people wearing only a gold lycra leotard with a bit of red fabric in the front and a g-string in back, black Doc Martens, and punk rock feathered headdress. Hanging out at Josie’s Juice Joint in San Francisco, where he was performing Juiced, he met the Pomo Afro Homos and danced as a taniwha in a Haitian voodoo-esque ritual with Djola Branner.

Photo by Cindy Marler, at the Cultural Olympiad of Barcelona, 1992. ‘Cindy saw my show and asked to shoot me. It was a magical trip: an ageing drag queen was MC, there were foam parties – well, orgies, actually, but at least you came out clean.’

MIKA . . . RHYMES WITH MADONNA

Conventionally the avant-garde is seen to be poised against the popular; high art and sophisticated tastes against low entertainments and vulgar consumerisms. Such oppositions are about status and class, fuelled equally by commerce and conceit. But the avant-garde has always been tickled by the popular, and the popular often picks up where the avant-garde leaves off. What we call ‘cutting edge’ in art, as in life, happens because performers such as Mika act as sharp-eyed, spectatorial magpies always on the lookout for new shiny objects to pick up, tart up with other glittery bits, and flaunt as their own. They are flaming fans as well as vanguardians. What they produce, often as not, captures the queer and kitsch fringes of the original and comes out as camp.

Mika in Carmen’s Vegas wig at her place, 1992.

Mika in Carmen’s bed, on his way to Barcelona, 1992.

Then, too, the emergence of MTV and its correlate technology the videotape, which made it possible to capture live performances and circulate them through informal networks, struck New Zealand popular culture in the 1980s with at least as much force as did television in the 1960s. It’s easy to forget how such innovations produced, in their first iterations, radically new ways of performing. With each reiteration, the edges didn’t so much blur as reconstitute themselves as new art forms, reverberating further with each new spin-off.

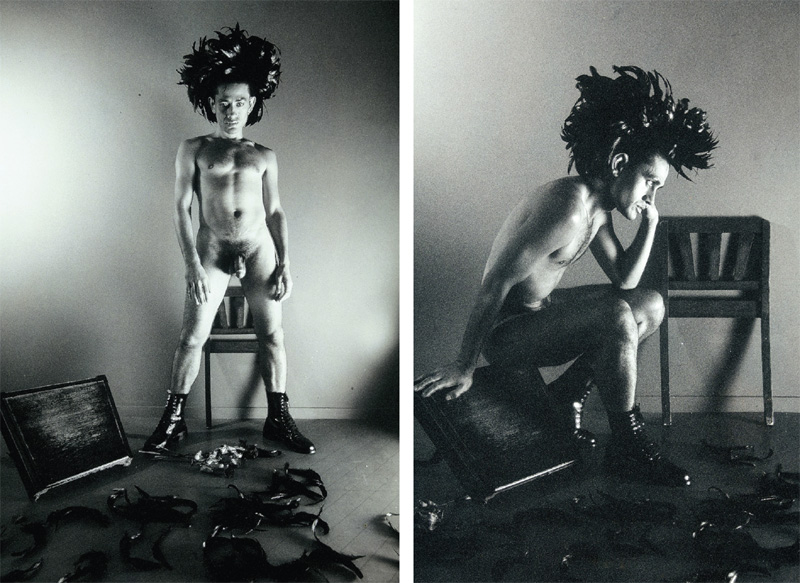

At the Halloween parade in the Castro, 1992. ‘Josie’s Juice Joint in San Francisco was the last stop on my world tour. I’m wearing one of the (only) two costumes I travelled with.’

So we see Grace Jones’ performances stirring Warholian aesthetics with street sensibilities and who knows what else into some kind of confrontational cabaret wrought large on the concert stage, then remixed into rough films and flung into the ether where aspirants such as Mika catch glimpses of what they might create for themselves more locally, making their own videos and pushing them out into the world in response. At the other end of the pop spectrum, no less provocatively and controversially: Madonna, she of ‘Like a Virgin’ and ‘Material Girl’, who has become a point of return for Mika for over 25 years. In the poster for Maka Takataapui: Te Madonna Maori (2006), a blonde-wigged, sharp-boobed, heavily eyelashed Mika looks out from his dressing table as if hung over from the night before. It’s almost seductive, sexually suggestive in a somewhat laconic, don’t-think-I-can-be-bothered kind of way.

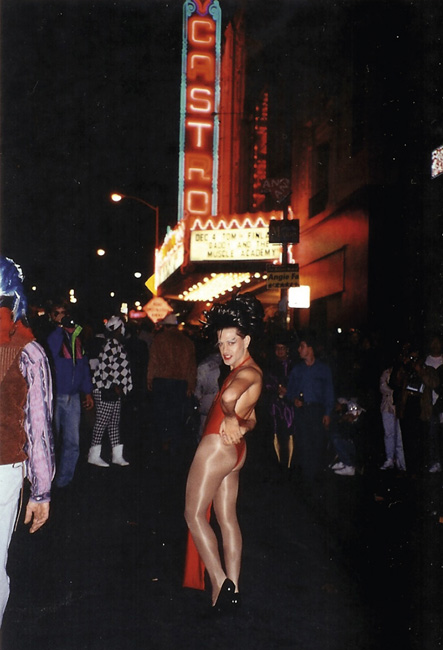

Mika with his friend Eric Gupton from Pomo Afro Homos, San Francisco, 1992. ‘Eric died of AIDS. I think I wanted to have these pics of Eric, Peter, John Draper, and others in this book so that we remember . . . We have PrEP now, but there was a time when we didn’t even know if we could kiss someone. AIDS changed LGBTIQ/takatāpui culture forever. Lest we forget our friends, lovers, whānau – Ngā moemoeā ngā hoa, ngā moemoeā.’

Gender identities began to slip and slide at the end of the 1980s, in Aotearoa New Zealand as elsewhere, shifting from bipolarity to fluidity. No sooner had ‘gay’ and ‘lesbian’ exited the closet and entered the everyday lexicon, than the doors opened to ‘bi’ and ‘trans’. Social movements of the previous decades that had been largely underpinned by binary oppositions started morphing, particularising. What had appeared singular now multiplied and modified. Performances by groups such as the Pomo Afro Homos, who emerged in 1990 as a San Francisco political theatre troupe, could be seen to be reflecting the complexities of their social situations: the problematics of being black and gay in the USA. Such performances stirred the very real through parody and pastiche (the ‘pomo’ or ‘postmodern’), and ultimately called out what had formerly appeared to be straightforward forms of categorisation as oppressive mechanisms of the dominant culture.

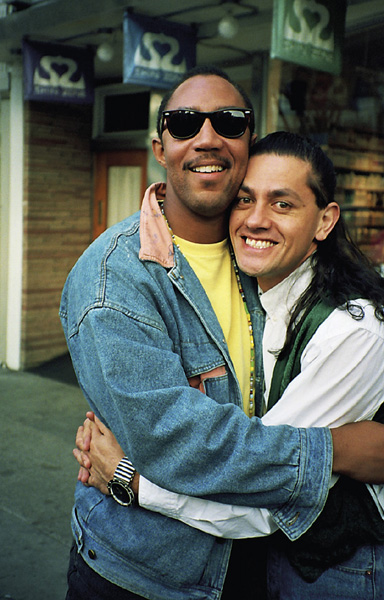

After the Juiced photo shoot. Photo by Albert Sword.

What Mika took from the Pomo Afro Homos was not so much his cue as confirmation of his own performative inclinations. For Mika, as for the Pomo Afro Homos and so many others of the time – especially queer artists and companies like Charles Ludlum, Everett Quinton and Ethyl Eichelberger of the Ridiculous Theatrical Company – such virtuosic performances of parody and pastiche represented more than the pop cultural pleasures of cutting and pasting. They were acting up and acting out, demonstrating the intimate bond between the personal and the political as though their lives (and ours) were at stake, which, for many at the time, they were.

TAKATĀPUI TANGA

At the end of 1992, Mika came back to New Zealand and auditioned for the role of a Māori chief in Jane Campion’s The Piano.

Diana Rowan, the casting director, asked me on camera if I could talk about takatāpui tanga – Māori gay life. I talked twenty minutes non-stop to the camera. As with everything else – where either I immediately get a phone call or there’s total silence – I got a call, offering me the role of Tahu, the transgendered, cross-dressing Māori.12

Controversy followed.

The institutionalised homophobia of Māori on the film meant that my role was dismissed by Jane’s Māori advisors; some said there was no record of homosexuality, whilst others claimed that gay Māori were killed at birth. When I was doing my audition, I had to hold myself from bursting into fits of laughter. I remember looking straight at the camera, thinking: how do they know the baby’s gay at birth?

Photo by Laurence Quinn for John Draper’s magazine GLO, 1993. Mika was the ‘jellied eel’ – a dessert by Fredrick Aldworth (who died after contracting AIDS). The recipe gives instructions for making a jellied lover.

On The Piano set, there were two camps (no pun intended): one pro-gay (obviously pro-Mika) and the other anti-gay (and therefore anti-Mika). He says he’d name them, but he ‘wouldn’t want to give them any more excitement than they’ve already had’. From his perspective: ‘What would happen was that the ones who became pro-gay also understood me.’ End of discussion.

Film sets are like cocktail parties, actors always looking over the shoulders of those with whom they’re working to leverage themselves into their next job. Mika felt close enough to Stuart Dryburgh, the cinematographer, to Jane Campion and to Holly Hunter and Harvey Keitel, along with others. But while on set he fell out with a number of Māori activists who were comfortable enough, he says, promoting land and human rights but not with the way Mika linked being Māori to being gay. His response to their judgment remains dismissive. ‘They became a little invisible to me,’ he says.

Whether it’s gay rights or Māori rights, if you stand up for yourself the real gold will always come through. The best moment during The Piano was while we were in rehearsals. I’d just come back from rehearsing my first gay haka with hundreds of people for my Hero Show. I turned up on set with Tungia Baker and Temuera Morrison – both were in the anti-gay camp – and Harvey asked, innocently, what I’d been doing. I said, ‘I’ve just been working on New Zealand’s first gay haka for the Hero Party.’ Well, if it was a scene from The Matrix one would have seen Tungia and Tem moving at lightning speed to protect Harvey from being exposed to more of that. I blocked them, kept Harvey completely in my attention.

In the film, Mika (as Tahu) can be seen lounging on a tree, dangling his leg over the water, twirling his hair. He’s behind Harvey Keitel (as George Baines), set above and apart from the group of Māori women and children who are teasing Keitel’s character about sex in a scene that looks largely improvised. A woman says, in te reo Māori: ‘You need a wife. No good having it sulk between your legs for the rest of its life.’ Mika makes an offer: ‘I save you.’ When Keitel answers, ‘I have a wife.’ Mika’s comeback is simple enough: ‘Kei te pai [that’s fine]. I save her too.’ The response is cutting: ‘Quiet! Balls were wasted on you.’ Twenty-five years on, the scene is remarkable both for its oddly primitive representation of Māori culture and its ambivalence, its diffident inclusion of Mika in a takatāpui role. The scene is clearly designed to showcase an ideal(isation) of Māori openness about sex and sexuality in contrast to the more constrained puritanism of the settlers – earnestly playing into what we might recognise now as colonial clichés – but it’s too squeamish, really, for its own good.

He had fun on the set of The Piano. The role gave him the opportunity to imagine himself as a native in full drag and act out in the way he might have even in the colonial period. Incidental as it was to the film as a whole, the scene was a chance to upstage, upend and queer an otherwise rather clichéd encounter between colonial puritanism and native sexuality. Even in the tight discipline of the shots, which keep our attention on Keitel’s character throughout, just for a moment Mika steals the scene. His performance as takatāpui adds texture, depth and difference to the film in ways that might seem radical even now. It’s clearly built as much around and for him as it is for Keitel. For a moment, at least, Mika’s ready for his close-up. But while he went into the film thinking it was a step towards Hollywood, he came out with the realisation that his idea of stardom was not that. Maybe it was all the time waiting around to be called (‘Talent!’) only to find himself effectively on the periphery, with only a tiny amount of wriggle room allotted to him because of the eccentricities of the character he was allowed to create for himself, nevertheless fitting into a plot not of his own making. Or maybe it was what he was finding elsewhere, at the same time, as he prepared to launch the first gay haka onto the Hero stage.

Jane Campion, Mika, Hori Ahipene and Cliff Curtis on the set of The Piano, 1992.

Photo by Albert Sword, 1989.

Harvey gave me his number in New York, but I never called.

— Mika