Mika licking his image at the ‘Black Carnival’ exhibition. Photo by Christine Webster.

CHAPTER FIVE

DO U LIKE WHAT U SEE?

My heart always leaps to see him.

– Witi Ihimaera, Nights in the Gardens of Spain

I am whatever u want me to be.

– Mika, ‘Do U Like What U See?’

GHOSTS . . . DANCING WITH LIFE

The early 1990s saw Mika rapidly consolidating his public image as a distinctively gay and Māori performer/entrepreneur, still somehow both ahead of the curve and off to one side of the proliferating identity politics of the time. While successive governments were taking aggressive steps to dismantle the social infrastructure that had sustained the health and education of generations of New Zealanders, the culture itself was becoming more liberal, or at least more ‘tolerant’ of difference in everyday contexts. His visibility was becoming such that the Māori Queen, Dame Te Ātairangikaahu, came to call him the ‘Māori Court Jester’ – someone who has licence both to amuse and to give voice to ideas in ways that others can’t or won’t.

Having walked away from the set of The Piano determined to own his image and his work, Mika used the visibility the film gave him to propel himself onto other stages. He made a spectacle of himself, while promoting other performers and social movements as well. His celebrity status increased alongside his notoriety, spiked by events such as his staging of the first gay haka at the Hero Party in 1992 and his appearance in Christine Webster’s notorious and startling photography exhibition ‘Black Carnival’ (1993). His activism and ambitions were intimately intertwined, the exhibitionism of his Hero Party performance, for example, directly tied to the raising of both consciousness and funds for AIDS programmes.

NOBLE SAVAGE

One of the most striking images of Mika in the early 1990s appears not in pictures but in words. Witi Ihimaera’s novel Nights in the Gardens of Spain reads like a chronicle of its time, a piercing portrait of Auckland’s gay culture, from the bathhouses to the beaches, the city and its suburbs, men in love and lust, dying and living. We first glimpse a character much like Mika in a gym car park. Ihimaera’s protagonist, David, has just arrived. The ‘Noble Savage’ greets him with a casual ‘Yo, David’ (16), tosses an invitation to a meeting to ‘raise money for a Polynesian centre for young gays’ (17), then hops into his flash car and speeds away. In Western arts and culture, the image of the noble savage is an archetypal construct at the sharp (and erotic) edge between desire and terror. In Gone Primitive, Marianna Torgovnick says: ‘They exist for us in a cherished series of dichotomies: by turns gentle, in tune with nature, paradisal, ideal – or violent, in need of control; what we should emulate or, alternately what we should fear; noble savages or cannibals.’ (3)1

Te Arikinui Dame Te Ātairangikaahu, the Māori Queen, with Mika and Torotoro. Mika first performed for the Queen in 1986 when he was at Tūrangawaewae with Te Ohu Whakaari. This was the last of his shows she attended. Back row, from left: Mika, Te Arikinui Dame Te Ātairangikaahu, her husband Whatumoana Paki, Piripi Munroe. Front row: Mokoera Te Amo, Jai Campbell, Kasina Campbell and Taupuhi Toki.

In the novel, Ihimaera’s rendering of the Noble Savage is a vivid and precise portrayal of Mika as a young man in full flight:

The Noble Savage is a Maori. His black hair is long and still wet from showering. Today he looks brand new, as if he has just stepped out of a Gauguin painting, straight out of Eden. Sometimes, as this morning, he wears a red flower behind his ear in unaffected delight. (16)

David’s voice is full of yearning. What he desires, though, is not so much the Noble Savage’s body as his freedom, his joyous certainty of self and purpose.

My heart always leaps to see him. Activist, outspoken and out front, he commands admiration and respect for the gay Maori and Polynesians of our city. Head of a new gay tribe, his is a strong voice, working with the Aids clinic, health authorities, city fathers, Prostitutes’ Collective and whoever else will listen. (17)

They are friends, not lovers, David says. ‘He is out of reach’ (17), but then for David, so is the life that the Noble Savage represents. The Noble Savage is out of the closet. David is not. He is an internal exile, narrating his way into self-consciousness. The Noble Savage is a celebrity, because of what he does on stage and because he is out in front, challenging the status quo as a gay Māori man in ways that are still almost unimaginable. ‘His politics,’ David tells us, ‘make him unavailable to whites’ (17). The sexual and the colonial are too intimately intertwined:

It is bad enough to be gay in his cultural milieu, but it is doubly disempowering to have a white lover of either sex. He cannot afford an ambiguous credibility. His people have already been fucked by whites. First as imperialists. Then as second-class gays within our own white-driven gay networks. He has accepted his destiny as gay icon of Polynesia. (17)

The Noble Savage, in Ihimaera’s portrait, is enviable for the way he makes a seemingly smooth surface of the messy politics of sex and identity at the beginning of the 1990s in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Near the end of the novel, David attends the Hero Party. His journey to this night has been fraught. He’s attained a modicum of equilibrium, having come out of the closet to his parents, to his wife and daughters, and to his colleagues. The scene in the novel is a lightly fictionalised rendering of the actual event as recalled by Mika and others, and preserved in a YouTube video of Mika’s ‘gay haka’:

The overseas terminal has been turned into a huge dance floor for the party. At one end a staircase has been built for the show. Four thousand gay men and lesbians have come to party and affirm the heroism of being gay. In street wear, carnival costume, leather wear, fantasy dresses, jock straps, tee-shirts and jeans, or hardly anything at all, they pack the overseas terminal with their sass, sexiness, outrageousness and bravado. Above, searchlights are slicing the sky like the 20th Century Fox logo. Inside the venue, lasers twist and refract, bend and warm into surreal rainbows of light. (299)

Despair has given way to hope, at least for the moment.

Suddenly the dance music stops. The show begins. And there, standing at the topmost tier, is The Noble Savage . . . with his group of proud Maori and Polynesian gay men and women. They are calling in the way of their people, the women sending out a proud cry above where we stand and cheer, the men gesticulating in a war dance, moving down and chanting: Make way, we are a new tribe. We are coming through. (299)

I AM WHAT I AM

The film of Mika’s performance at the Hero Party on Princes Wharf in 1992 begins with a soaring karanga (call).2 The camera pulls back to reveal a wide stage area surrounded by spectators, men in white leggings and masks undulating in a mixture of bump-and-grind and aerobics-type moves and two women in black on stilts swinging fire poi. Brief shots of drag queens in full sequins, and then of Mika in a spotlight on a platform high above the main stage. He begins to sing. The stage fills with men in native drag carrying torches; they are joined and supplanted in turn by waves of diversely identified groups, including twenty or so women in Pacific Island costumes and greenery, more drag queens in sequins and high feathers, and performers with enormous tapa ‘masks’ on their backs.

The camera cuts between Mika, the soloist on high, and the masses performing their set pieces in roughly choreographed order below. He’s wearing a shiny black corset over black fringed briefs, with black boots. His hair is up, with long shiny chopsticks poking out, and he’s wearing pronounced make-up: thick foundation, dark lips and eyes. Attached to a harness at his back are long bamboo poles with even longer red flags, in a Kabuki-esque spread high above his head. Behind him is a Keith Haring–inspired backdrop, yellow with square panels, on which are drawn iconic signs of the times: condoms, Safe Sex, men with arms raised, doubled women symbols, and so on.

Mika and a cast of hundreds performed his original song ‘Lava Lover’ live at the Hero Party on Princes Wharf, Auckland, 1992. ‘Lava Lover (Hero Mix)’ featured on the Do U Like What U See album. Photos by Vivienne Haldane.

Mika performing at the Hero Party. Photo by Vivienne Haldane.

As he struts back and forth on his platform, he waves the flag in his hand – the other holds the microphone – at the dancers, chants in te reo, and sings: ‘You’re the one that I miss / You’re the one that I kiss.’3 The refrain continues over the shrieks of the spectators and the controlled pandemonium, as diverse groups take the stage:

Lava Lover

Like no other

Tropical desire

Walking in the fire

Walking in the rain.

The show reaches its climax with the haka ‘Tēnei Tōku Ure’. The words came to him out of nowhere, while he was on the big wheel in Paris, Mika recalls. He had been asked to make something spectacular with the community for the Hero Party.

I put posters everywhere – everywhere – gay men go, and hundreds joined in. Hero was about raising funds for HIV. We had all lost so many. (I stopped counting at forty-five.) We rehearsed for months, we made the costumes, I recorded the song ‘Lava Lover’ and performed it with the haka, and we all paid $50 for tickets as well. That was about the last time I remember community being so strong, when we all not only volunteered but [also] contributed financially.

Mika and Mohi Thompson after the 1992 gay haka, Hero Dance Party. Photo by Fryderyk Kublikowski.

From start to finish, Mika’s Hero Party performance is both a celebration and an act of militant sexuality: ‘This is my ure [penis] / erect with desire.’ Chanted in unison, in te reo and English, the haka’s final words are an anthem and a challenge:

Man is my lover.

Man is my friend.

Tāne hoa takatāpui.

My life companion.

Wāhine are our sisters.

Tāne are our brothers.

Fa’afafine are our sisters.

Pasifika tātou iwi e are our iwi.

Ka whawhai mō te mana tūturu tāne mana

I fight for the mana of being a man

Ko tāne mate tāne ko tāne mate tāne4

Tēnei au ahau

I am what I am.

I am what I am.

What we see in the film is a massive, flowing spectacle staged like an eruption. The performers seem simultaneously disciplined and anarchic, multiple tribes, each dancing to its own rules – gliding, grinding, waving, undulating, stomping – their faces in close-up revealing joy and determination in equal parts. They swarm the stage, up the stairs to Mika’s platform where they gyrate at his feet and down again, playing for the cameras wherever they find them. (The cameras are, it seems, everywhere. The film seems to have been as well-planned as the performance.) Mika is in almost constant motion, alternately strutting and mock-mincing, conducting the near-chaos below with a flag in his hand, seducing and prancing away from the dancers as they circle him. But there’s a point, near the end, where the camera catches him standing still, watching the haka below in what looks like awe at what he’s made happen. Then he carries on, picking up the chant and bits of the arm-waving as they finish it off.

The morning after the 1992 Hero Party in Auckland. Mika, still wearing his Issey Miyake bustier, sits beside an unknown woman at the bus stop in Point Chevalier. Guy Moana also waits, with his dog. Photo by Vivienne Haldane.

Mika gives credit for the success of ‘Lava Lover’ to his collaboration with John Draper, his partner for four shows between 1992 and 1994:5

Where Merata and Dalvanius had informed me of my Māori stuff, John was the non-Māori version. He was HIV-positive and one of those rare artists – obscure, like Derek Jarman – who basically didn’t give a fuck and told me not to as well.

Not giving a fuck meant not getting paid most of the time. They had little or no money, but Mika says it was a great apprenticeship. Their shows mixed cabaret with burlesque. The costumes – ‘as little as we wore’ – were whatever they could magic up, but the hair was fabulous, the make-up was striking, and the song and dance were all.

Then came Pearl Harbour: the ‘ultimate wake-up call’. It was catastrophic for everyone involved.

I took thirty-five queens, and we got ready for a tour of Japan that never happened. The myth and legend of that time was that I’d ripped off the girls and made millions, but the reality was the producer was an owner of hostess bars. Some of the girls did get to go, but the fact was that I had fucked up. The girls had given up apartments, jobs, and I had a contract that meant nothing. It was horrific for the girls. And it was my fault.

The failure was indeed legendary. The Australian booker turned out to be a con artist, took the money and left everyone hanging. Mika did manage to take a reduced company, six performers, to Tokyo, where another booker took them on. But the costs were huge, and the rage simmers still, easily inflamed, as I’ve discovered in chance encounters with those who were there. The lesson Mika learnt was fairly basic, yet essential to his coming of age as an independent artist and producer. As a result, he says, ‘I have never since done anything that risks other people’s careers, finances.’

Pearl Harbour in 1992 before the disaster. The gold set and costumes were designed, for the most part, by John Draper. Photo by Phil Fogle.

Performing at the Squid nightclub in Auckland, a place of ‘cheap sex parties, before mobile phones could capture it all’, says Mika. Photo by Nicholas Alexander, 1995.

In the Spiegeltent for Wellington Arts Festival, 1998, the last leg of an Australia–New Zealand tour through six cities.

He didn’t just mature overnight. His reckoning was more complicated, more dramatic. He fled. Or rather, he took the next opportunity that presented itself, to go to the 1994 Gay Games in New York City, where he ran right into karma: ‘I arrived (as did several other artists) to the Gay Games cultural festival head office. The organiser had left. There were no shows booked. I paused. I breathed in, I breathed out, I had a coffee. That is how I’ve always handled “issues”.’

Then, just like that, he was back on track. He met Tim Rosta, the man behind the creation of the MTV Music Awards and an HIV campaigner, the head of LIFEbeat: Music fights HIV/AIDS.6

Tim got me a warm-up gig at the Roxy for Grace Jones [Grace Jones!], and he introduced me to Camille Barbone, Madonna’s manager [Madonna!], and a host of other amazing people. I had a ball. It’s probably the only time in my life I didn’t want to go back to New Zealand. Probably after the disaster of Pearl Harbour, after any disaster, you just want to run away and stay away. I’m not one of those people, and so I did return.

Knocked back, first by his own naïveté, and then by the less-than-scrupulous organisers of the Gay Games, he didn’t fall into abject failure, but instead found himself in the room with the people he had idolised, the stars whose performances had given rise to his own. He was rescued, not only by Tim Rosta, but also – upon his return to New Zealand – by Nicholas Alexander, who, he says, ‘came into my life, and fixed everything. For a while.’ Alexander became his manager, and was the connection to Christine Webster, who in turn invited Mika to become one of the models for her ‘Black Carnival’.

BLACK CARNIVAL

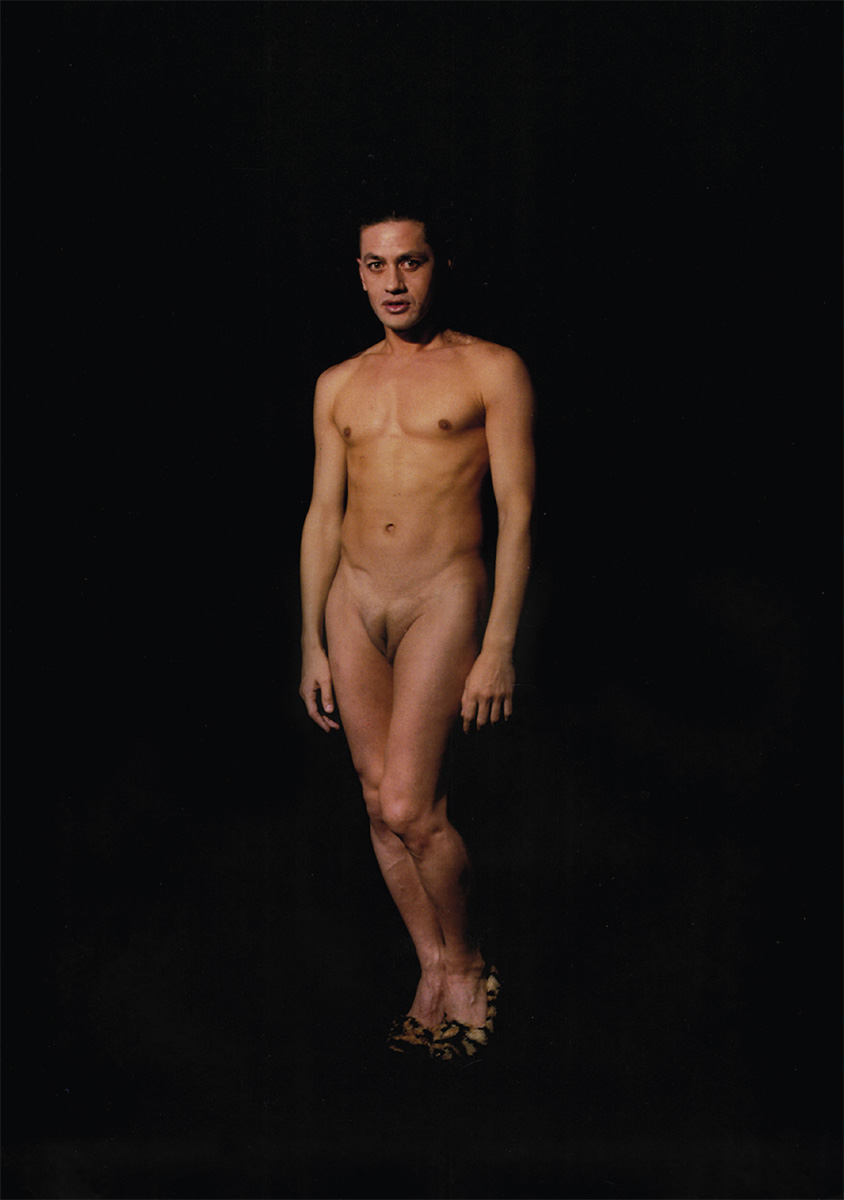

The larger-than-life image hangs in the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu. It is titled Mika: Kai Tahu. It’s probably the most well-known photograph of Mika. He stands strong, legs apart, feet in black boots, with a gold tasselled metallic breastplate, his hair loose to just below his shoulders. His gaze challenges that of the camera. It looks like a dare: Do you like what you see? There is a second photograph. In it, the dare becomes a double dare. Mika, naked except for a pair of high heels, stands with his legs together, one knee bent in front of the other. His hair is pulled back, so that his face, revealed and shaped by shadow, is somehow softened, and his genitals have been tucked so that he appears to have a vagina. He is both exposed and hidden, facing us and shying away, inviting and uneasy.

Ewen McDonald, in an essay published on Webster’s website, sees something spooky (in both psychoanalytic and social terms) in ‘Black Carnival’. For McDonald, ‘The self is revealed as being no more than a set of indeterminate presences, of ghostly traces harboured just beneath a social skin.’ The ghosts, he says, ‘have been caught in the room dancing with life’.7 Contemporary critic Robert Leonard casts a wider interpretive net in his provocative essay ‘Hello Darkness: New Zealand Gothic’.8 He sees in ‘Black Carnival’, as in artworks by Ronnie van Hout, Bill Hammond, Gavin Hipkins, et al., something simultaneously dark and trashy, surreal in a kind of postcolonial, ‘collective historical-cultural unconscious’. In Leonard’s view, works like ‘Black Carnival’ represent a distinctively New Zealand, ironically Christchurch-centred zeitgeist, rising to the surface as a predominantly Pākehā reaction to their displacement by emergent Māori art-makers, and then, ironically, taken up by Māori artists such as Michael Parekowhai, Lisa Reihana and Shane Cotton. He says:

New Zealand art’s Gothic turn was partly a response to biculturalism, the dominant discourse in New Zealand art in the late 1980s, early 1990s. In the early 1990s, a new generation of contemporary Maori artists were getting all the airtime and biculturalism dominated every discussion. Against this backdrop, a new group of Pakeha artists emerged who were interested in exploring their own cultural identity while reacting against both the pieties of biculturalism and earnest 1980s theory art. While contemporary Maori art typically asserted cultural identity as noble, much of this work had a bogan edge.

For Leonard, ‘Some of it – but not all – was overtly postcolonial, concerned with the skeletons in the historical closet, a shameful past haunting the present.’ The question becomes, then, who is the haunted, who the haunter?

ARE U SURE U KNOW WHAT U SEE?

In the 1990s, Mika’s slyly transgressive, sharply sexualised represent ations of Māori identity appeared as a deviation from the otherwise straight and narrow of more ‘traditional’ forms of Māori performance. The performances audiences saw then look very much like what we see now: a heady, campy swirl of song, dance and patter. The spectacle Mika creates onstage – and off – is difficult to pin down. Whatever it is, it’s not straight. The costumes are native drag: an (almost) avant-garde amalgamation of feathers and shells, high fashion, street and bordello wear that picks up where the sartorial experiments of the Pacific Sisters leave off,9 and resembles also the postcolonial dress-ups performed by Guillermo Gómez-Peña and Coco Fusco in their controversial museum show The Couple in the Cage.10 The songs somehow manage the hat trick of being original and a pastiche at the same time. The words spring from Mika’s heart as poetry and are mixed with snippets, phrases and tunes, samplings of whatever’s hot or hotly nostalgic, from pop to kapa haka. The moves recall his aerobics and disco days, with bits of haka and poi, stirred up and slid somewhere between cabaret and burlesque.11

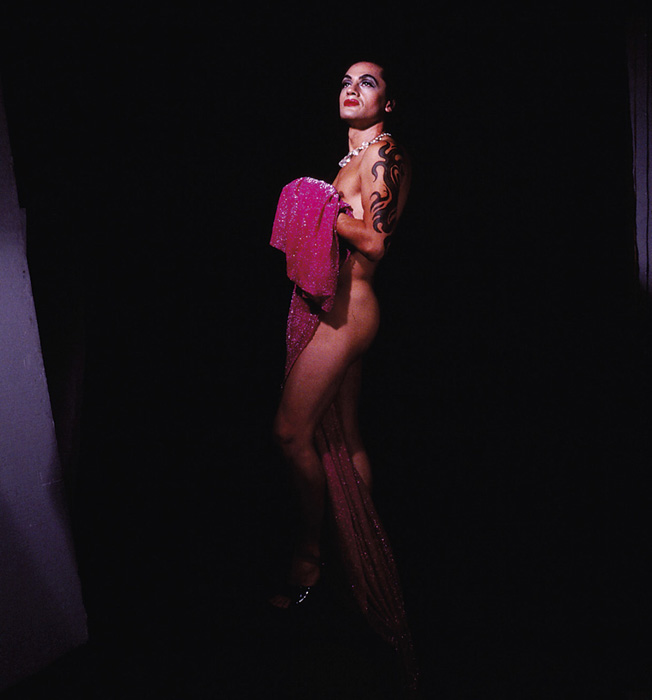

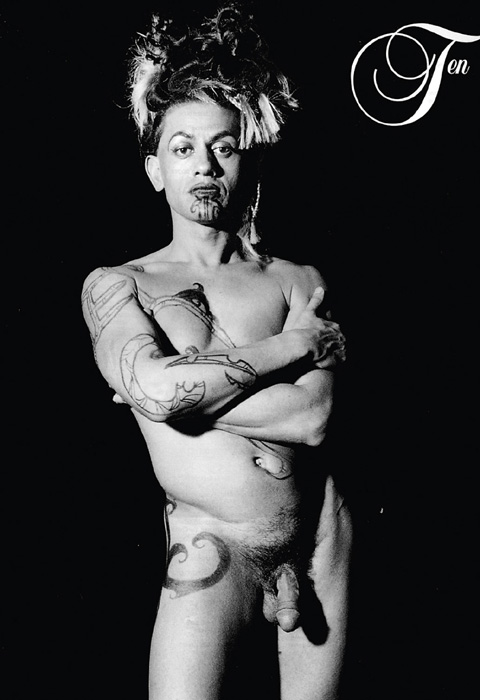

From Christine Webster’s controversial ‘Black Carnival’ series, 1993–97.

The word ‘burlesque’ conventionally calls up clichéd images of striptease clubs or barely legit cabarets, with salacious MCs and comics alternating with scantily clad dancers, and of performances involving parody, travesty, mockery and grotesquery – ridicule rather than reverence. Burlesque puts us in the realm of the vulgar in the most vulgar sense of the word, both popular and low. As such, it keeps company with ‘camp’ and ‘kitsch’ and ‘minstrelsy’ – all terms that have also been reclaimed from the pejorative and put to good use by performance scholars in recent years. It should be noted that minstrelsy, a particularly dirty word for its performative assault on African American identity, has seen an odd renaissance in theory and practice, reclaimed for its potential to disturb the hegemony of whiteness in the USA. In his influential study Love and Left: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, for example, Eric Lott observes:

It was a cross-racial desire that coupled a nearly insupportable fascination and a self-protective derision with respect to black people and their cultural practices, and that made blackface minstrelsy less a sign of absolute white power and control than of panic, anxiety, terror, and pleasure. (6–7)

Mika, the bathing beauty. Photo shoot for Cleo magazine, February 1997, by Monty Adams. Styling by Rachael Churchward (of Black magazine) and Lisa Reihana.

Photo shoot by Monty Adams for Cleo, 1997. This was the last time Mika put on a woman’s moko. Styled by Rachael Churchward and Lisa Reihana.

In Mika’s performances the ‘scary savage’ simmers under a cheeky surface.12 His burlesque returns us, performers and spectators together, repeatedly to the body as the primary mover and shaker of social meaning, to the generative proclivities of the sensual and the sexual, the life force stripped of the veneer of civility and returned, like the repressed, with comic finesse.

Mika’s postcolonial camp spectaculars weave the fundamentals of Māori ritual and traditional performance, from pōwhiri to kapa haka, with pop culture in a ‘Pōkarekare Ana’-meets-Madonna kind of way. He puts on the native, explicitly playing on the idea of colonial desire – what Robert J. C. Young terms ‘the ambivalent movement of attraction and repulsion . . . the sexual economy of fantasies in race, and of race in fantasies of desire’13 – by adorning his indisputably male body with signs of feminine allure – feathers and sequins, grass skirts and top hats, moko and eyeliner – and daring the audience to play along. As he mimics, even parodies, Māori ritual and traditional performance, Mika reveals and revels in the construction of the ‘native’ in the contemporary cultural imagination. In so doing, he exposes the erotics underlying the performative exchange between performer and audience, wherever we might find it, by reminding us that performances – all performances – are built upon bodies: bodies that invite the look and bodies that do the looking.

When these performing bodies are marked by gender and/or ethnicity, dominant cultural ideas of gender and ethnicity are potentially destabilised; the bodies become performative, and in their performativity, the ways that desire and power are inevitably intertwined become visible. Burlesque makes the act of looking visible, essential to the erotic exchange between the performer and the spectator, who is never fully in the dark and, implicated in the act, not necessarily safe in his seat. The more conscious we become of the looking, the more we have the possibility also of seeing the workings of power and desire off-stage.

Thus, when Mika sings ‘Do u like what u see?’ he’s absolutely serious and utterly ironic. His preening, tongue-flicking and come-hithering verge on self-parody, but there’s an undercurrent of real challenge, a confrontation with the audience at the sharp edge of sex and sexuality. It’s savage, in a cheerfully calculated yet uninhibited way. The music video, directed by Christine Webster, begins with a body shot, Mika naked from the waist up, black draped, leather-belted, sarong below, staring directly at the camera as it zooms in on his face and flames arise to meet his image. His hair is loose. He has a woman’s moko painted on his chin – an affectation he came to reject in later years because, he says, ‘it no longer seemed important to express cross-gender’ in that way. He’s lip-synching to a high-pitched, feminine singing voice, very possibly not his own, flirting with the camera. His image gives way to those of others of constantly varying ethnicities and sexual orientations: images of individuals facing the camera and couples who face and embrace each other. He speaks the first lines of the song in his own, lower voice:

These eyes, they see what they see

These hands, they touch what they feel

Tongue licks what sticks (what sticks)

Mouth kisses what’s wet (what’s wet)

Bisexual, homosexual, heterosexual

Are u sure u know what u see?

Man, woman, brown, white.

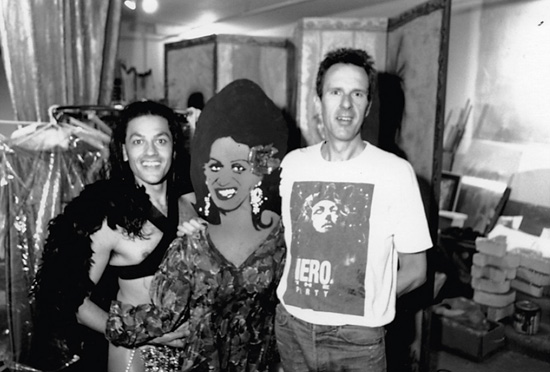

Mika with John Draper, 1994. They are standing with a Carmen cut-out that John made for the Hero Festival show Carmen’s International Coffee Lounge, written by Mika.

Nicholas Alexander with Mika in Nicholas’s flat, 1994. Photo by Christine Webster.

His voice weaves through the other voices, high and low, in chorus and solo, as the others also are seen lip-synching at points. The voices and images merge and separate, individuals and pairs fading into focus and out, flowing along with Mika’s. He gives stage to the others, and takes it back, is at once the centre of attention and just one of the company.

Mid-video, the song changes up, transcends the pop. There’s a small haka insert: four boys in piupiu, a moko’d man in dungarees.

He kohu tau

He kohu tau

Ko au anake

He patapatai

O te iwi (e kore)

Mika and the others join in – men and women, the four boys in piupiu – still in their individual screens, but together in the montage, performing the haka and chanting.

Ko taku wairua

E rere atu nei

Ko taku ngākau

E piri mai

Ko taku tapu

He parirau

He tohu tike tike

Tāku mana motuhake

Te reo Māori and English overlap in the final lines, and we see Carmen, in a red sequinned gown, big bangled jewellery, black sequinned hat decorated with brilliantly coloured baubles, bright lippy. She fills the screen, gloriously swaying and singing along.

Kite ao katoa e

Do u like what u see?14

Mika’s not just singing to the converted. He’s asserting himself, along with the other performers, and he’s also hitting at voyeurs and the violence of the closet.

I like what I see

I like what I feel

Tomorrow will u scorn at people u see

People u want, people like me.

Oh yeah baby, I’m always on your mind

Oh yeah baby, I’m something u find

Every once in a while, but baby beware

The things u hide your friends despise

So, beware of your games, pleasures and throws

’Cos one day baby, you’ll be sprung by your bros

Sprung by your bros.

From the Kapai Kabaret album cover photo shoot, 1995. The first Cabaret Live recording was commissioned by Henare Te Ua, National Radio, and Libby Hakaraia. Mika asked Henare to be his takatāpui kaumātua (gay elder). Arjan Hoeflak shot the photo in Mika’s studio at 6B Ponsonby Road.

In many ways, ‘Do U Like What U See?’ sets the standard for Mika’s work. It’s half-ballad, half-anthem. The music is predominantly pop, but it gives way at its heart to a Māori beat that then seems to underscore the return to pop. The dance moves are simple enough for anyone to do, in a way that makes its accessibility part of the point. At the same time, Mika visibly surpasses, transforms the dance and the song’s refrain into probing seduction. His star turn dissolves itself into a chorus of diverse personae, all somehow joining and reflecting Mika even as they perform themselves as distinctive individuals. Everyone is beautiful, singly and together, in their own way.15 Everyone desires, and is desirable. It’s utopian, without being at all sentimental or coercive. The questions are asked openly.

Would you kiss me in that alley?

Would you hold me in that street?

Do you want to dominate me?

Or serve at my feet?

MISCHIEF AND WONDER

As illness began to overtake John Draper, Nicholas Alexander took over as Mika’s primary collaborator. Beginning with the Starfish Enterprise Cabaret, their partnership was hugely productive, including shows like Tutu, Kapai Kabaret (recorded by the late, great Henare Te Ua and Libby Hakaraia for National Radio), Pure Mika and more. According to Alexander, ‘The aim was to create an unexpected majestic cabaret packed with mischief and wonder. Magical realism in live 3D.’ The high point came in 1997, when they went to Edinburgh and Mika was pronounced ‘Maori queen of Scots’ in the press, thereby, he says, ‘winning the lotto of the festival circuit’: ‘I had the world in my hands, and I gave it away.’

Hero 3 magazine centrefold, 1997. Photo by Christine Webster.

You get to a point in your life where you can only be so fabulous.

— Mika, on Gay Talk Tonight

Kapai Kabaret photo shoot by Arjan Hoeflak, 1995.